Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan |

|---|

Bob Dylan (born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter, author, musician, and poet who has been a major figure in popular music for five decades. Much of Dylan's most recognized work dates from the 1960s, when he became an informal chronicler and a reluctant figurehead of American unrest. A number of his songs, such as "Blowin' in the Wind" and "The Times They Are a-Changin'",[1] became anthems of the anti-war and civil rights movements. His most recent studio album, Modern Times, released on August 29, 2006, entered the U.S. album charts at #1, making him, at age 65, the oldest living person to top those charts.[2] It was later voted Album of the Year by Rolling Stone magazine and, in the UK, by the magazine Uncut.

Dylan's early lyrics incorporated politics, social commentary, philosophy and literary influences, defying existing pop music conventions and appealing widely to the counterculture of the time. While expanding and personalizing musical styles, he has shown steadfast devotion to many traditions of American song, from folk and country/blues to rock and roll and rockabilly, to English, Scottish and Irish folk music, even jazz, swing, Broadway, hard rock and gospel.

Dylan performs with the guitar, keyboard and harmonica. Backed by a changing lineup of musicians, he has toured steadily since the late 1980s on what has been dubbed the "Never Ending Tour". He has also performed alongside other major artists, such as Willie Nelson, Paul Simon, The Grateful Dead, Tom Petty, Stevie Nicks, Bruce Springsteen, The Band, U2, The Rolling Stones, Joni Mitchell, Patti Smith, Emmylou Harris, Joan Baez, Jack White, Merle Haggard, Neil Young, Johnny Cash, Van Morrison, George Harrison, Ringo Starr and Eric Clapton. Although his accomplishments as performer and recording artist have been central to his career, his songwriting is generally regarded as his greatest contribution.[3]

His recordings received the Grammy, Golden Globe and Academy Awards, and he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame and Songwriters Hall of Fame. Dylan was listed as one of TIME Magazine's 100 most influential people of the 20th century. In 2004, Bob Dylan was ranked #2 in Rolling Stone Magazine's 100 Greatest Artists of All Time, second to The Beatles.[4] In January 1990, Dylan was made a Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres by French Minister of Culture Jack Lang; in 2000, he was awarded the Polar Music Prize by the Royal Swedish Academy of Music[5]; and in 2007 Dylan was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award in Arts. He has also been nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Literature[6][7][8].

Life and career

Origins and musical beginnings

Robert Allen Zimmerman (Jewish name: Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham)[9] was born on May 24, 1941, in Duluth, Minnesota,[10] and raised there and in Hibbing, Minnesota, on the Mesabi Iron Range northwest of Lake Superior. Research by Dylan’s biographers has shown that his paternal grandparents, Zigman and Anna Zimmerman, emigrated from Odessa in the Ukraine to the United States after the anti-Semitic pogroms of 1905. His mother’s grandparents, Benjamin and Lybba Edelstein, were Lithuanian Jews who arrived in America in 1902.[11] (In his 2004 autobiography, Chronicles, Dylan wrote that his paternal grandmother's maiden name was Kirghiz and her family originated from Istanbul, although she grew up in the Kağızman district of Kars in Eastern Turkey. He also wrote that his paternal grandfather was from Trabzon on the Black Sea coast of Turkey.[12])

His parents, Abraham Zimmerman and Beatrice "Beatty" Stone were part of the area's small but close-knit Jewish community. Zimmerman lived in Duluth until age seven. When his father was stricken with polio, the family returned to nearby Hibbing, where Zimmerman spent the rest of his childhood.[13] Abraham was recalled by one of Bob's childhood friends as strict and unwelcoming, whereas his mother was remembered as warm and friendly.[14]

Dylan spent much of his youth listening to the radio — first to the powerful blues and country stations broadcasting from Shreveport and, later, to early rock and roll.[15] He formed several bands in high school. The first, The Shadow Blasters, was short-lived. The next band, The Golden Chords, lasted longer and played covers: their performance of Danny and the Juniors' "Rock and Roll Is Here to Stay" at their high school talent show was so loud that the principal cut the microphone off.[16][17] In his 1959 school year book, Robert Zimmerman listed his ambition as "To join Little Richard."[18] The same year, he performed two dates under the name of Elston Gunnn[19] with Bobby Vee, playing piano and providing handclaps.[20] Zimmerman enrolled at the University of Minnesota in September 1959 and moved to Minneapolis. His early focus on rock and roll gave way to an interest in American folk music, typically performed with an acoustic guitar. He has recalled, "The first thing that turned me onto folk singing was Odetta. I heard a record of hers in a record store. Right then and there, I went out and traded my electric guitar and amplifier for an acoustical guitar, a flat-top Gibson".[21] He may have taken guitar lessons with Marvin Karlins at the University of Minnesota.[22] He soon began to perform at the 10 O'clock Scholar, a coffee house a few blocks from campus, and became actively involved in the local Dinkytown folk music circuit, fraternizing with local folk enthusiasts and occasionally "borrowing" many of their albums.[23][24]

During his Dinkytown days, Zimmerman began introducing himself as "Bob Dylan". In his autobiography, Chronicles (2004), he wrote: "What I was going to do as soon as I left home was just call myself Robert Allen.... It sounded like a Scottish king and I liked it." However, by reading Downbeat magazine, he discovered that there was already a saxophonist called David Allyn. Around the same time, he became acquainted with the poetry of Dylan Thomas. Robert Zimmerman felt he had to choose between Robert Allyn and Robert Dylan: "I couldn't decide — the letter D came on stronger" he explained. He decided on "Bob" because there were several Bobbies in popular music at the time.[25]

Relocation to New York and record deal

Dylan quit college at the end of his freshman year. He stayed in Minneapolis, working the folk circuit there with temporary journeys in Denver, Colorado; Madison, Wisconsin; and Chicago, Illinois. In January 1961, he headed for New York City to perform and to visit his ailing musical idol Woody Guthrie in a New Jersey hospital. Guthrie had been a revelation to Dylan and was the biggest influence on his early performances. Dylan would later say of Guthrie's work, "You could listen to his songs and actually learn how to live."[24] In the hospital room, Dylan also met Woody's old road-buddy Ramblin' Jack Elliott visiting Guthrie the day after returning from his trip to Europe. He and Elliott became friends, and much of Guthrie's repertoire was actually channeled through Elliott. Dylan paid tribute to Elliott in Chronicles (2004).[26]

From May to September of 1961 he played at various clubs around Greenwich Village.[27] Dylan gained some public recognition after a positive review[28] in The New York Times by critic Robert Shelton for a show he played at Gerde's Folk City in September. Also in September he played harmonica on a few tracks on folk singer Carolyn Hester's first album for Columbia Records, which producer John Hammond was working on.[29] This brought full awareness to John Hammond of Bob Dylan's talents, so he signed Dylan to Columbia Records that October. His performances, like those on his first Columbia album Bob Dylan (1962), consisted of familiar folk, blues and gospel material combined with some of his own songs. As Dylan continued to record for Columbia, he recorded more than a dozen songs for Broadside Magazine, a folk music magazine and record label, under the pseudonym Blind Boy Grunt. In August 1962, he went to the Supreme Court building in New York and changed his name to Robert Dylan.

By the time Dylan's next record, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, was released in 1963, he had begun to make his name as both a singer and a songwriter. Many of the songs on this album were labelled protest songs, inspired partly by Guthrie and influenced by Pete Seeger's passion for topical songs.[30] "Oxford Town," for example, was a sardonic account of James Meredith's ordeal as the first black student to risk enrollment at the University of Mississippi.[31]

His most famous song of the time, "Blowin' in the Wind", partially derived its melody from the traditional slave song "No More Auction Block", while its lyrics questioned the social and political status quo. The song was widely recorded and became an international hit for Peter, Paul and Mary, setting a precedent for other artists. While Dylan's topical songs solidified his early reputation, Freewheelin' also included a mixture of love songs and jokey, surreal talking blues. Humor was a large part of Dylan's persona,[32] and the range of material on the album impressed many listeners, including The Beatles. George Harrison said, "We just played it, just wore it out. The content of the song lyrics and just the attitude — it was incredibly original and wonderful."[33]

The Freewheelin' song "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall", built melodically from a loose adaptation of the stanza tune of the folk ballad "Lord Randall", with its veiled references to nuclear apocalypse, gained even more resonance as the Cuban missile crisis developed only a few weeks after Dylan began performing it.[34] Like "Blowin' in the Wind", "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" marked an important new direction in modern songwriting, blending a stream-of-consciousness, imagist lyrical attack with traditional folk progressions.[35]

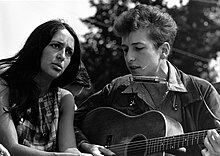

Soon after the release of Freewheelin, Dylan emerged as a dominant figure of the so-called "new folk movement" headquartered in Greenwich Village. As an interpreter of traditional songs, Dylan's singing voice was untrained (which is not uncommon for popular singers), and also quite unusual (some believe that Don McLean's American Pie is referring to Dylan when it mentions "a voice that came from you and me"). Robert Shelton described Dylan's style as "a rusty voice suggesting Guthrie's old performances, etched in gravel like Dave Van Ronk's"[36] Many of his most famous early songs first reached the public through versions by other performers who were more immediately palatable. While Dylan was not trying to perform sprechgesang (nor was it likely Dylan was aware of the obscure song form), his singing voice has been described as such.[37][38] Joan Baez became Dylan's advocate, as well as his lover. Baez jumpstarted Dylan's performance career by inviting him onstage during her concerts, and recorded several of his early songs; she was influential in bringing Dylan to national and international prominence.[39]

Others who recorded and released his songs around this time included The Byrds; Sonny and Cher; The Hollies; Peter, Paul and Mary; Manfred Mann; The Brothers Four; Judy Collins and The Turtles, most attempting to impart more of a pop feel and rhythm to the songs where Dylan and Baez performed them mostly as sparse folk pieces keying rhythmically off the vocals. These covers were so ubiquitous by the mid-1960s that CBS started to promote him with the tag "Nobody Sings Dylan Like Dylan".

Protest and Another Side

By 1963, Dylan and Baez were both prominent in the civil rights movement, singing together at rallies including the March on Washington where Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his "I have a dream" speech.[40] In January, Dylan appeared on British television in the BBC play Madhouse on Castle Street, playing the part of a "hobo guitar-player".[41] His next album, The Times They Are a-Changin', reflected a more sophisticated, politicized and cynical Dylan. This bleak material, addressing such subjects as the murder of civil rights worker Medgar Evers and the despair engendered by the breakdown of farming and mining communities ("Ballad of Hollis Brown", "North Country Blues"), was accompanied by two love songs, "Boots of Spanish Leather" and "One Too Many Mornings", and the renunciation of "Restless Farewell". The Brechtian "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll" describes the true story of a young socialite's (William Zantzinger) killing of a hotel maid (Hattie Carroll). Though never explicitly mentioning their respective races, the song leaves no doubt that the killer is white and the victim is black.[42]

By the end of 1963, Dylan felt both manipulated and constrained by the folk-protest movement. Accepting the "Tom Paine Award" from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee at a ceremony shortly after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a drunken, rambling Dylan questioned the role of the committee, insulted its members as old and balding, and claimed to see something of himself (and of every man) in assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.[43]

His next album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, recorded on a single June evening in 1964, had a lighter mood than its predecessor. The surreal Dylan reemerged on "I Shall Be Free #10" and "Motorpsycho Nightmare", accompanied by a sense of humor that has often reappeared over the years. "Spanish Harlem Incident" and "To Ramona" are, unusually for Dylan at the time, non-ironic love songs, while "I Don't Believe You" suggests the rock and roll soon to dominate in Dylan's music. "It Ain't Me Babe," on the surface a song about spurned love, has been described as a thinly disguised rejection of the role his reputation thrust at him. His newest direction was signaled by two lengthy songs: the impressionistic "Chimes of Freedom", which sets elements of social commentary against a denser metaphorical landscape in a style later characterized by Allen Ginsberg as "chains of flashing images"; and "My Back Pages," which attacks the simplistic and arch seriousness of his own earlier topical songs and seems to predict the backlash he was about to encounter from his former champions as he took a new direction.[44]

In 1964–65 Dylan’s appearance changed rapidly, as he made his move from leading contemporary song-writer of the folk scene to rock’n’roll star. His scruffy jeans and work shirts were replaced by a Carnaby Street wardrobe. A London reporter wrote: “Hair that would set the teeth of a comb on edge. A loud shirt that would dim the neon lights of Leicester Square. He looks like an undernourished cockatoo.”[45] Dylan also began to play with frequently hapless interviewers in increasingly cruel and surreal ways. Appearing on the Les Crane TV show and asked about a movie he was planning to make, he told Crane it would be a cowboy horror movie. Asked if he played the cowboy, Dylan replied. “No, I play my mother.”[46]

Dylan goes electric

His March 1965 album Bringing It All Back Home was yet another stylistic leap.[47] the album featured his first recordings made with electric instruments. The first single, "Subterranean Homesick Blues", owed much to Chuck Berry's "Too Much Monkey Business" and was provided with an early music video courtesy of D. A. Pennebaker's cinéma vérité presentation of Dylan's 1965 tour of England, Dont Look Back.[48] Its free association lyrics both harked back to the manic energy of Beat poetry and were a forerunner of rap and hip-hop.[49] In 1969, the militant Weatherman group took their name from a line in "Subterranean Homesick Blues" ("You don't need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows").

The B side of the album was a different matter, including four lengthy acoustic songs whose undogmatic political, social and personal concerns are illuminated with the semi-mystical imagery that became another trademark. One of these tracks, "Mr. Tambourine Man" - which would eventually become one of his best known songs, had already been a hit for The Byrds - while "Gates of Eden", "It's All Over Now Baby Blue", and "It's Alright Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)" have been fixtures in Dylan's live performances for most of his career.

That summer Dylan made history by performing his first electric set (since his high school days) with a pickup group drawn mostly from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, featuring Mike Bloomfield (guitar), Sam Lay (drums), Jerome Arnold (bass), plus Al Kooper (organ) and Barry Goldberg (piano), while headlining at the Newport Folk Festival (see The electric Dylan controversy).[50] Dylan had appeared at Newport twice before, in 1963 and 1964, and two wildly divergent accounts of the crowd's response in 1965 emerged. The settled fact is that Dylan, met with a mix of cheering and booing, left the stage after only three songs. As one version of the legend has it, the boos were from the outraged folk fans whom Dylan had alienated by his electric guitar. An alternative account claims audience members were merely upset by poor sound quality and a surprisingly short set. Whatever sparked the crowd's disfavor, Dylan soon reemerged and sang two much better received solo acoustic numbers, "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" and "Mr. Tambourine Man", although his choice of the former has often been described as a carefully selected death knell for the kind of consciously sociopolitical, purely acoustic music that the cat-callers were demanding of him, with "New Folk" in the role of "Baby Blue".

Dylan's 1965 Newport performance provoked an outraged response from the folk music establishment.[51] Ewan MacColl wrote in Sing Out!: "Our traditional songs and ballads are the creations of extraordinarily talented artists working inside traditions formulated over time... But what of Bobby Dylan?... Only a non-critical audience, nourished on the watery pap of pop music could have fallen for such tenth-rate drivel." On July 29th, just four days after his controversial performance at Newport, Dylan was back in the studio in New York recording "Positively 4th Street". The song teemed with images of paranoia and revenge ("I know the reason/That you talk behind my back/I used to be among the crowd/You're in with"), and was widely interpreted as Dylan's put-down of former friends from the folk community, friends he had known in the clubs along West 4th Street.[52]

Many in the folk revival had embraced the idea that life equaled art, that a certain kind of life defined by suffering and social exclusion in fact replaced art.[53] Folksong collectors and singers often presented folk music as an innocent characteristic of lives lived without reflection or the false consciousness of capitalism.[54] This philosophy, both genteel and paternalistic, was ultimately what Dylan had run afoul of by 1965. But at an Austin press conference in September of that year, on the day of his first performance with Levon and the Hawks, he described his music not as a pop charts-bound break with the past, but as “historical-traditional music.”[55] Dylan later told interviewer Nat Hentoff: “What folk music is... is based on myths and the Bible and plague and famine and all kinds of things like that which are nothing but mystery and you can see it in all the songs….All these songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels…and seven years of this and eight years of that and it’s all really something that nobody can touch.... (the songs) are not going to die.”[56] It was this mystical, living tradition of songs that served as the palette for Bringing It All Back Home, but in a nod to changing times first openly displayed at Newport, electrically amplified instruments would now become part of the mix.

Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde

In 1965, Dylan released the single "Like a Rolling Stone," and it was a huge hit in both the U.S. and the UK; at over six minutes, it also expanded the limits of songs played on hit radio. In 2004, Rolling Stone listed it at number one on its list of the 500 greatest songs of all time.[57] Its signature sound — with a full, jangling band and an organ riff — also characterized his next album, Highway 61 Revisited. Titled after the road that led from Dylan's native Minnesota to the musical hotbed of New Orleans, the songs passed stylistically through the birthplace of blues, the Mississippi Delta, and referenced a number of blues songs, including Mississippi Fred McDowell's "61 Highway". The songs were in the same vein as the hit single, with surreal litanies of the grotesque flavored by Mike Bloomfield's blues guitar, a rhythm section and Dylan's obvious enjoyment of the sessions. The closing song, "Desolation Row", is an apocalyptic vision with references to many figures of Western culture.

In support of the record, Dylan was booked for two U.S. concerts and set about assembling a band. Mike Bloomfield was unwilling to leave the Butterfield Band, so Dylan mixed Al Kooper and Harvey Brooks from his studio crew with bar-band stalwarts Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm, best known for backing Ronnie Hawkins. In August 1965 at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium, the group was heckled by an audience who, Newport notwithstanding, still demanded the acoustic troubadour of previous years. The band's reception on September 3 at the Hollywood Bowl was more uniformly favorable.[59]

Neither Kooper nor Brooks wanted to tour with Dylan, and he was unable to lure his preferred band, a crew of west coast musicians best known for backing Johnny Rivers, featuring guitarist James Burton and drummer Mickey Jones, away from their regular commitments. Dylan then hired Robertson and Helm's full band, The Hawks, for his tour group, and began a string of studio sessions with them in an effort to record the follow-up to Highway 61 Revisited.

While Dylan and the Hawks met increasingly receptive audiences on tour, their studio efforts floundered. Producer Bob Johnston had been trying to persuade Dylan to record in Nashville for some time. In February 1966 Dylan agreed and Johnston surrounded him with a cadre of top-notch session men. At Dylan's insistence, Robertson and Kooper came down from New York City to play on the sessions.[60] The Nashville sessions created what Dylan later called "that thin wild mercury sound" — Blonde on Blonde (1966). Al Kooper said the record was a masterpiece because it was "taking two cultures and smashing them together with a huge explosion": the musical world of Nashville, and the world of the "quintessential New York hipster" Bob Dylan.[61]

For many critics, Dylan's mid-'60s trilogy of albums — Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde — represents one of the great cultural achievements of the 20th century. In Mike Marqusee's words: "Between late 1964 and the summer of 1966, Dylan created a body of work that remains unique. Drawing on folk, blues, country, R&B, rock'n'roll, gospel, British beat, symbolist, modernist and Beat poetry, surrealism and Dada, advertising jargon and social commentary, Fellini and Mad magazine, he forged a coherent and original artistic voice and vision. The beauty of these albums retains the power to shock and console."[62]

Dylan undertook a "world tour" of Australia and Europe in the spring of 1966. Each show was split into two parts. Dylan performed solo during the first half, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica. In the second half, backed by the Hawks, he played high voltage electric music. This contrast provoked many fans, who jeered and slowly handclapped.

The tour culminated in a famously raucous confrontation between Dylan and his audience at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in England (officially released on CD in 1998 as The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert). At the climax of the concert, one fan, angry with Dylan's electric sound, shouted: "Judas!" and Dylan responded, "I don't believe you... You're a liar!" He turned to the band and, just within earshot of the microphone, said "Play it fucking loud!"[63] They then launched into the last song of the night with gusto — "Like a Rolling Stone."

Crash and the late 1960s

After his European tour, Dylan returned to New York, but the pressures on him continued to increase. Of course, Dylan was under no pressure whatever compared to the millions of American males his age who were serving in Vietnam. His publisher was demanding a finished manuscript of the poem/novel Tarantula. Manager Albert Grossman had already scheduled an extensive summer/fall concert tour. On July 29, 1966, while Dylan rode his Triumph 500 motorcycle in Woodstock, New York, its brakes locked, throwing him to the ground. Though the extent of his injuries was never fully disclosed, it was confirmed that he indeed broke his neck. Dylan took advantage of his extended convalescence to escape the pressures of stardom: "When I had that motorcycle accident ... I woke up and caught my senses, I realized that I was just workin' for all these leeches. And I really didn't want to do that."[64]

Nevertheless, questions lingered about the accident and the extent of Dylan's injuries. At the time, Dylan was said to be particularly unhappy with his management and the demands upon him. According to Howard Sounes' biography, Down the Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, Dylan's treatment pattern in the immediate aftermath of the accident, as well as his treatment thereafter, severely call into question the notion that Dylan's injuries were truly life threatening.

Once Dylan was well enough to resume creative work, he began editing film footage of his 1966 tour in Eat the Document, a rarely exhibited follow-up to Don't Look Back. In 1967 he began recording music with the Hawks at his home and at the basement of the Hawks' nearby "Big Pink". The relaxed atmosphere yielded renditions of many of Dylan's favored old and new songs and some newly written pieces.[65] These songs, initially compiled as demos for other artists to record, provided hit singles for Julie Driscoll ("This Wheel's on Fire"), The Byrds ("You Ain't Goin' Nowhere", "Nothing Was Delivered"), and Manfred Mann ("Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)"). Columbia belatedly released selections from them in 1975 as The Basement Tapes. Later in 1967, the Hawks (soon to be rechristened as The Band) independently recorded the album Music from Big Pink, thus beginning a long and successful recording and performing career of their own.

In December 1967 Dylan released John Wesley Harding, his first album since the motorcycle crash. It was a quiet, contemplative record of shorter songs, set in a landscape that drew on both the American West and the Bible. The sparse structure and instrumentation, coupled with lyrics that took the Judeo-Christian tradition seriously, marked a departure not only from Dylan's own work but from the escalating psychedelic fervor of the 1960s musical culture.[66] It included "All Along the Watchtower", with lyrics derived from the Book of Isaiah (21:5–9). The song was later recorded by Jimi Hendrix, whose celebrated version Dylan himself acknowledged as definitive in the liner notes to Biograph. As proof, since 1974 Dylan and his bands have performed arrangements much closer to Hendrix's than to the John Wesley Harding version.[67]

Woody Guthrie died on October 3rd 1967, and Dylan made his first public appearances in eighteen months at a pair of Guthrie memorial concerts the following January.

Dylan's next release, Nashville Skyline (1969), was virtually a mainstream country record featuring instrumental backing by Nashville musicians, a mellow-voiced, contented Dylan, a duet with Johnny Cash, and the hit single "Lay Lady Lay". In 1969 Dylan appeared on the first episode of Cash's new television show and then gave a high-profile performance at the Isle of Wight rock festival (after rejecting overtures to appear at the Woodstock Festival far closer to his home).[68]

1970s

In the early 1970s critics charged Dylan's output was of varied and unpredictable quality. Rolling Stone magazine writer and Dylan loyalist Greil Marcus notoriously asked "What is this shit?" upon first listening to 1970's Self Portrait. In general, Self Portrait, a double LP including few original songs, was poorly received. Later that year, Dylan released New Morning, which some considered a return to form. His unannounced appearance at George Harrison's 1971's Concert for Bangladesh was widely praised, but reports of a new album, a television special, and a return to touring came to nothing.

Between March 16th and 19th, 1971, Dylan reserved three days at Blue Rock Studios, a small studio in New York's Greenwich Village. The sessions resulted in three singles ("Watching The River Flow", "When I Paint My Masterpiece" and "George Jackson"), but no album. The only long-player released by Dylan in either '71 or '72 was his second greatest hits compilation, "Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits Vol. II", which included a number of re-workings of as-then unreleased Basement Tapes tracks, such as "I Shall Be Released" and "You Ain't Goin' Nowhere" with Happy Traum on backup. In November of 1971 Dylan recorded a series of as-yet-unreleased sessions with Beat poet Allen Ginsberg at the Record Plant in New York, intended for Ginsberg's "Holy Soul Jelly Roll" album. The sessions resulted in tracks such as the Dylan/Ginsberg compositions "Vomit Express", "September On Jessore Road" and "Jimmy Berman", as well as a number of Ginsberg originals and William Blake poems set to music. Ginsberg sang lead on most songs, with Dylan playing guitar and harmonica and providing backing vocals [69].[70] It is unknown at this time if the sessions will ever be released officially, however there are a number of bootlegs in circulation.

In 1972 Dylan signed onto Sam Peckinpah's film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, providing the songs (see Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (album)) and taking a role as "Alias", a minor member of Billy's gang. Despite the film's failure at the box office, the song "Knockin' on Heaven's Door" has proven its durability, having been covered by over 150 recording artists.[71] Among others by Guns 'N Roses.

Dylan started 1973 by contributing his own composition, "Wallflower", to Doug Sahm's "Doug Sahm and Band" album released on Atlantic Records, as well as sharing lead vocal and playing guitar on the track. (Dylan's own version of the song would later be released on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3.) Dylan also signed with David Geffen's new Asylum label when his contract with Columbia Records expired in 1973, and he recorded Planet Waves with The Band while rehearsing for a major tour. The album included two versions of "Forever Young". The phrase may be a reference to John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, ("For ever panting, and for ever young") but Dylan turned it into a strangely (for Dylan) sincere and openly heartfelt work (thought to have been inspired by his newfound family life and his children) which has become one of his most popular concert songs.[72][73] Columbia Records simultaneously released Dylan, a haphazard collection of studio outtakes (almost exclusively cover songs), which was widely interpreted as a churlish response to Dylan's signing with a rival record label.[74] In January 1974 Dylan and The Band embarked on their high-profile, coast-to-coast Bob Dylan and The Band 1974 Tour of North America; promoter Bill Graham claimed he received more ticket purchase requests than for any prior tour by any artist. A live double album of the tour, Before the Flood which included Dylan with The Band, was released on Asylum Records. Later in the mid 70s Before the Flood was released by Columbia records.

After the tour, Dylan and his wife became publicly estranged. He filled a small red notebook with songs about his marital problems, and quickly recorded a new album entitled Blood on the Tracks in September 1974.[75] Word of Dylan's efforts soon leaked out, and expectations were high. But Dylan delayed the album's release, and then, by years end he had re-recorded half of the songs at Sound 80 Studios in Minneapolis with production assistance from his brother David Zimmerman. During this time, Dylan returned to Columbia Records which eventually reissued his Asylum albums.

Released in early 1975, Blood on the Tracks received mixed reviews. In the NME, Nick Kent described "the accompaniments [as] often so trashy they sound like mere practise takes." In Rolling Stone, reviewer Jon Landau wrote that "the record has been made with typical shoddiness". However, over the years critics have come to see it as one of Dylan's greatest achievements, perhaps the only serious rival to his great mid 60s trilogy of albums. In Salon.com, Bill Wyman wrote: "Blood on the Tracks is his only flawless album and his best produced; the songs, each of them, are constructed in disciplined fashion. It is his kindest album and most dismayed, and seems in hindsight to have achieved a sublime balance between the logorrhea-plagued excesses of his mid-'60s output and the self-consciously simple compositions of his post-accident years."[76] The songs have been described as Dylan's most intimate and direct.[77][78] A year later, Dylan recorded a duet of the song "Buckets of Rain" with Bette Midler on her Songs for the New Depression album.[3] When Dylan was initially approached to do a duet with Midler, he wanted to record a version of "Friends." While they rehearsed this song, it was the "Blood on the Tracks" closer which was eventually released.[4]

That summer Dylan wrote his first successful "protest" song in twelve years, championing the cause of boxer Rubin "Hurricane" Carter who he believed had been wrongfully imprisoned for a triple homicide in Paterson, New Jersey. After visiting Carter in jail, Dylan wrote "Hurricane", presenting the case for Carter's innocence. Despite its 8:32 minute length, the song was released as a single, peaking within the top forty on the U.S. Billboard Chart, and performed at every 1975 date of Dylan's next tour, the Rolling Thunder Revue.[79] The tour was a varied evening of entertainment featuring many performers drawn mostly from the resurgent Greenwich Village folk scene, including T-Bone Burnett; Allen Ginsberg; Ramblin' Jack Elliott; Steven Soles; David Mansfield; former Byrds frontman Roger McGuinn; British guitarist Mick Ronson; Scarlet Rivera, a violin player Dylan discovered while she was walking down the street to a rehearsal, her violin case hanging on her back;[80] and Joan Baez (the tour marked Baez and Dylan's first joint performance in more than a decade). Joni Mitchell added herself to the Revue in November, and poet Allen Ginsberg accompanied the troupe, staging scenes for the film Dylan was simultaneously shooting. Sam Shepard was initially hired as the writer for this film, but ended up accompanying the tour as informal chronicler.[81]

Running through late 1975 and again through early 1976, the tour encompassed the release of the album Desire (1976), with many of Dylan's new songs featuring an almost travelogue-like narrative style, showing the influence of his new collaborator, playwright Jacques Levy.[82][83] The spring 1976 half of the tour was documented by a TV concert special, Hard Rain, and the LP Hard Rain; no concert album from the better-received and better-known opening half of the tour was released until 2002, when Live 1975 appeared as the fifth volume in Dylan's official Bootleg Series.

The fall 1975 tour with the Revue also provided the backdrop to Dylan's nearly four-hour film Renaldo and Clara, a sprawling and improvised narrative mixed with concert footage and reminiscences. Released in 1978, the movie received generally poor, sometimes scathing, reviews[84][85] and had a very brief theatrical run. Later in that year, Dylan allowed a two-hour edit, dominated by the concert performances, to be more widely released.

In November 1976 Dylan appeared at The Band's "farewell" concert, along with other guests including Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison and Neil Young. Martin Scorsese's acclaimed[86] cinematic chronicle of this show, The Last Waltz, was released in 1978 and included about half of Dylan's set. In this year Dylan also wrote and duetted on the song "Sign Language" for Eric Clapton's "No Reason To Cry" album - no other versions of the song apart from the one which appears on this album have ever been released. In 1977 he also contributed backing vocals to Leonard Cohen's Phil Spector-produced album "Death of a Ladies' Man".

Dylan's 1978 album Street Legal was lyrically one of his more complex and cohesive;[87] it suffered, however, from a poor sound mix (attributed to his studio recording practices),[88] submerging much of its instrumentation in the sonic equivalent of cotton wadding until its remastered CD release nearly a quarter century later.

The "Born Again" period

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, there were widely published reports that Dylan had become a born-again Christian.[89][90][91] From January to April 1979, Dylan participated in Bible study classes at the Vineyard School of Discipleship in Reseda, Southern California. Pastor Kenn Gulliksen has recalled: “Larry Myers and Paul Emond went over to Bob’s house and ministered to him. He responded by saying, Yes he did in fact want Christ in His life. And he prayed that day and received the Lord.”[92][93][94] Dylan released two albums of music displaying strong Christian influence, exploring Gospel music in his own idiosyncratic way on these albums. Slow Train Coming (1979) is generally regarded as the more accomplished of these albums, winning him the Grammy Award as "Best Male Vocalist" for the song "Gotta Serve Somebody". The second album, Saved (1980), was not so well-received. When touring from the fall of 1979 through the spring of 1980, Dylan would not play any of his older, secular works, and delivered what some describe as "sermonettes" on stage, such as:

Years ago they... said I was a prophet. I used to say, "No I'm not a prophet" they say "Yes you are, you're a prophet." I said, "No it's not me." They used to say "You sure are a prophet." They used to convince me I was a prophet. Now I come out and say Jesus Christ is the answer. They say, "Bob Dylan's no prophet." They just can't handle it.[95]

Robert Hilburn interviewed Dylan about the new direction in his music for the Los Angeles Times. Hilburn’s article, published November 23, 1980, began:

Bob Dylan has finally confirmed in an interview what he’s been saying in his music for 18 months: He’s a born-again Christian. Dylan said he accepted Jesus Christ in his heart in 1978 after “a vision and feeling” during which the room moved: “There was a presence in the room that couldn’t have been anybody but Jesus.”[96]

Dylan's embrace of Christianity was unpopular with some of his fans and fellow musicians.[97] Shortly before his December 1980 shooting, John Lennon, a self-described atheist, recorded "Serve Yourself", a negative response to Dylan's "Gotta Serve Somebody".[98] By 1981, while Christian influences were apparent, his basic style had not changed as Stephen Holden wrote in the New York Times:

Mr. Dylan showed that neither age (he's now 40) nor his much-publicized conversion to born-again Christianity has altered his essentially iconoclastic temperament.[99]

And according to Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner, writing in his review for Slow Train Coming, Dylan had not "sold out" totally to born-again Christianity so much as he had simply shifted focus. According to him, Dylan was still Dylan, and the same intensity and passion had been present in Dylan's protest songs of the 1960s. Wenner commented:

Slow Train Coming is pure, true Dylan, probably the purest and truest Dylan ever. The religious symbolism is a logical progression of Dylan's Manichaean vision of life and his pain-filled struggle with good and evil... since politics, economics and war have failed to make us feel any better — as individuals or as a nation — and we look back at long years of disrepair, then maybe the time for religion has come again, and rather too suddenly — "like a thief in the night."[100]

Since the early 1980s Dylan's personal religious beliefs have been the subject of debate[101] among fans and critics. On the level of religious practice, he has since seemingly supported the Chabad Lubavitch movement[102] and participated in many Jewish rituals. According to Rabbi Manis Friedman, Dylan did immerse in a mikvah, as required of a former apostate. In 1996 he told David Gates of Newsweek:

"Here's the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don't find it anywhere else. Songs like "Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain" or "I Saw the Light"--that's my religion. I don't adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I've learned more from the songs than I've learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs".

In September 28, 1997, interview appearing in The New York Times, journalist Jon Pareles reported that "Dylan says he now subscribes to no organized religion."[103]

More recently, it has been reported that Dylan has "shown up" a few times at various High Holiday services at various Chabad synagogues including Woodbury NY in 2005.[104]

Later career

1980s

In the fall of 1980 Dylan briefly resumed touring, restoring several of his most popular 1960s songs to his repertoire, for a series of concerts billed as "A Musical Retrospective". Shot of Love, recorded the next spring, featured Dylan's first secular compositions in more than two years, mixed with explicitly Christian songs. The haunting "Every Grain of Sand" reminded some critics of William Blake’s verses.[105]

In the 1980s the quality of Dylan's recorded work varied, from the well-regarded Infidels in 1983 to the panned Down in the Groove in 1988. Critics such as Michael Gray condemned Dylan's 1980s albums both for showing an extraordinary carelessness in the studio and for failing to release his best songs.[106]

The Infidels recording sessions produced several notable outtakes, and many have questioned Dylan's judgment in leaving them off the album. Most well-regarded of these were "Blind Willie McTell" (which was both a tribute to the dead blues singer and an extraordinary evocation of African American history reaching back to "the ghosts of slavery ships"[107]), "Foot of Pride" and "Lord Protect My Child";[108] these songs were later released on the boxed set The Bootleg Series Volumes 1-3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991. An earlier version of Infidels, prepared by producer/guitarist Mark Knopfler, contained different arrangements and song selections than what appeared on the final product.

Dylan contributed vocals to USA for Africa's famine relief fundraising single "We Are the World". On 13 July 1985, he appeared at the climax of the Live Aid concert at JFK Stadium, Philadelphia. Backed by Keith Richards and Ron Wood, Dylan performed a ragged version of "Hollis Brown", his ballad of rural poverty, and then said to a worldwide audience exceeding one billion people: "I hope that some of the money ... maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe ... one or two million, maybe ... and use it to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks." His remarks were widely criticised as inappropriate, but they did inspire Willie Nelson to organise a series of events, Farm Aid, to benefit debt-ridden American farmers.[109]

In 1986 Dylan made a foray into the world of rap music, appearing on Kurtis Blow's Kingdom Blow album. In an arrangement set up, in part, by Debra Byrd (one of Dylan's back-up singers) and Wayne K. Garfield (an associate of Blow's), Dylan contributed vocals to the track "Street Rock."[110] In his memoir, Chronicles, Dylan writes, "Blow familiarized me with that stuff, Ice-T, Public Enemy, N.W.A., Run-D.M.C.. These guys definitely weren't standing around bullshitting. They were all poets and knew what was going on."[111] Dylan's opening rap for "Street Rock" goes..."I've indulged in higher knowledge through scan of encyclopedia, keep in constant research of our report and news media, kids starve in Ethiopia and we are getting greedier, the rich are getting richer and the needy's getting needier".

In 1987 Dylan starred in Richard Marquand's movie Hearts of Fire, in which he played a washed-up-rock-star-turned-chicken farmer called "Billy Parker", whose teenage lover (Fiona) leaves him for a jaded English synth-pop sensation (Rupert Everett). Dylan also contributed three original songs to the soundtrack - "The Usual", "Night After Night", and 'I Had a Dream About You, Baby". The film was a critical and commercial flop.[112]

Dylan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1988. Later that spring he took part in the first Traveling Wilburys album, working with Roy Orbison, Jeff Lynne, Tom Petty, and George Harrison on lighthearted, well-selling fare. Despite Orbison's death, the other four Wilburys issued a sequel in 1990. He also toured with famous rock bands the Grateful Dead and Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers in the late 1980s.

Dylan finished the decade on a critical high note with the Daniel Lanois-produced Oh Mercy (1989).[113] Lanois's influence is audible throughout Oh Mercy.[114][115] "Ring Them Bells," one of the most celebrated songs on the album, appears to implore Christians to maintain a visible presence in the world ("Ring them bells St. Catherine/From the top of the room/Oh the lines are long/And the fighting is strong/And they're breaking down the distance/Between right and wrong").[116] The track "Most of the Time", a lost love composition, was later prominently featured in the film High Fidelity, while "What Was It You Wanted?" has been interpreted both as a catechism and a wry comment on the expectations of critics and fans.[117] Dylan also made a number of music videos during this period, but only "Political World" found any regular airtime on MTV.

1990s

Dylan's 1990s began with Under the Red Sky (1990), an about-face from the serious Oh Mercy. The album was dedicated to "Gabby Goo Goo", and contained several apparently simple songs, including "Under the Red Sky" and "Wiggle Wiggle". The "Gabby Goo Goo" dedication was later explained as a nickname for Dylan's four-year-old daughter.[118] Sidemen on the album included George Harrison, Slash from Guns N' Roses, David Crosby, Bruce Hornsby, Stevie Ray Vaughan, and Elton John. Despite the stellar line-up, the record received bad reviews and sold poorly. Dylan would not make another studio album of new songs for seven years.[119]

In 1991 Bob Dylan was inducted into the Minnesota Music Hall of Fame and in 1992 Dylan performed a brief tour with Santana.[120]

The next few years saw Dylan returning to his roots with two albums covering old folk and blues numbers: Good as I Been to You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993), featuring interpretations and acoustic guitar work. Many critics and fans commented on the quiet beauty of the song "Lone Pilgrim",[121] penned by a 19th century teacher and sung by Dylan with a haunting reverence. An exception to this rootsy mood came in Dylan's 1991 songwriting collaboration with Michael Bolton; the resulting song "Steel Bars", was released on Bolton's album Time, Love & Tenderness. In 1995 Dylan recorded a live show for MTV Unplugged. He claimed his wish to perform a set of traditional songs for the show was overruled by Sony executives who insisted on a greatest hits package.[122] The album produced from it (see MTV Unplugged (Bob Dylan album)) included "John Brown", an unreleased 1963 song detailing the ravages of both war and jingoism.

With a collection of songs reportedly written while snowed-in on his Minnesota ranch,[123] Dylan returned to the recording studio with Lanois in January 1997. Late that spring, before the album's release, he was hospitalized with a life-threatening heart infection, pericarditis, brought on by histoplasmosis. His scheduled European tour was cancelled, but Dylan made a speedy recovery and left the hospital saying, "I really thought I'd be seeing Elvis soon."[124] He was back on the road by midsummer, and in early fall performed before Pope John Paul II at the World Eucharistic Conference in Bologna, Italy. The Pope treated the audience of 200,000 people to a sermon based on Dylan's lyric "Blowin' in the Wind".[125]

September saw the release of the new Lanois-produced album, Time Out of Mind. With its bitter assessment of love and morbid ruminations, Dylan's first collection of original songs in seven years became highly acclaimed. It also achieved an unforeseen popularity among young listeners, particularly the opening song, "Love Sick".[126] This collection of complex songs won him his first solo "Album of the Year" Grammy Award (he was one of numerous performers on The Concert for Bangladesh, the 1972 winner). The love song "Make You Feel My Love" was covered by both Garth Brooks and Billy Joel.

In December 1997 President Clinton presented Dylan with a Kennedy Center Honor in the East Room of the White House, paying this tribute: "He probably had more impact on people of my generation than any other creative artist. His voice and lyrics haven't always been easy on the ear, but throughout his career Bob Dylan has never aimed to please. He's disturbed the peace and discomforted the powerful."[127]

Between June and September, 1999, Dylan toured with Paul Simon. They performed a couple of songs together at each show, including I Walk the Line (Johnny Cash) and Blue Moon Of Kentucky (Bill Monroe). (Simon & Garfunkel had recorded "The Times They Are a-Changin'" on their debut album, Wednesday Morning, 3AM, and Dylan had covered The Boxer on his Self Portrait album.) Dylan ended the nineties by returning to the big screen after a break of ten years in the role of Alfred the Chaffeur alongside Ben Gazzara and Karen Black in Robert Clapsaddle's "Paradise Cove".[128]

2000 and beyond

In 2000 his song "Things Have Changed", penned for the film Wonder Boys, won a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song and an Academy Award for Best Song. For reasons unannounced, the Oscar (by some reports a facsimile) tours with him, presiding over shows perched atop an amplifier.[129]

"Love and Theft" was released on September 11, 2001. Dylan produced the album himself under the pseudonym Jack Frost,[130] and its distinctive sound owes much to the accompanists. Tony Garnier, bassist and bandleader, had played with Dylan for 12 years, longer than any other musician. Larry Campbell, one of the most accomplished American guitarists of the last two decades, played on the road with Dylan from 1997 through 2004. Guitarist Charlie Sexton and drummer David Kemper had also toured with Dylan for years. Keyboard player Augie Meyers, the only musician not part of Dylan's touring band, had also played on Time Out of Mind. The album was critically well-received[131] and nominated for several Grammy awards. Critics noted that at this late stage in his career, Dylan was deliberately widening his musical palette. The styles referenced in this album included rockabilly, Western swing, jazz, and even lounge ballads.[132][133]

"Love and Theft" generated controversy when some similarities between the lyrics of the album to Japanese writer Junichi Saga's book Confessions of a Yakuza were pointed out.[134] It is unclear if Dylan intentionally lifted any material. Dylan's publicist had no comment.

"I Can't Get You Off of My Mind", Dylan's contribution to the Hank Williams tribute album "Timeless" was also released in September 2001. A year later he also contributed a cover of "Train Of Love" for a similar Johnny Cash tribute album called "Kindred Spirits". In February of 2003, an 8-minute long epic ballad called "Cross The Green Mountain", written and recorded by Dylan, was released as the closing song on the soundtrack to the Civil War movie Gods and Generals, and later appeared as one of the 42 rare tracks on the iTunes Music Store release of Bob Dylan: The Collection. A music video for the song was also produced in promotion of the motion picture.

2003 also saw the release of the film Masked & Anonymous, a creative collaboration with television producer Larry Charles, featuring many well-known actors. Dylan and Charles cowrote the film under the pseudonyms Rene Fontaine and Sergei Petrov.[135] As difficult to decipher as some of his songs, Masked & Anonymous had a limited run in theaters, and was panned by many major critics.[136] A few treasured it as Dylan's bringing a dark and mysterious vision of the USA as a war-torn banana republic to the screen.[137][138]

On Wednesday 23rd of June, 2004, Dylan was awarded an honorary degree by the University of St. Andrews and made a "Doctor of Music."[139] Professor Neil Corcoran, of the university's school of English department, and author of the collection of academic essays on Dylan entitled "Do You Mr Jones: Bob Dylan with the Poets and the Professors", declared in his presentation speech that "For many of us, Bob Dylan has been an extension of our consciousness and part of our growing up." This is only the second time that Dylan has accepted an honorary degree, the other being conferred on him by Princeton University in 1971.

In 2005 preproduction began on a film entitled I'm Not There: Suppositions on a Film Concerning Dylan, written and directed by Todd Haynes. The movie makes use of six characters to represent different aspects of Dylan's life. The actors playing Dylan are Cate Blanchett, Heath Ledger, Christian Bale, Richard Gere, Ben Whishaw, and Marcus Carl Franklin.[140]

Martin Scorsese's film biography No Direction Home was shown on September 26 and September 27 2005 on BBC Two in the United Kingdom and PBS in the United States.[141] The documentary concentrates of the years between Dylan's arrival in New York in 1961 and the 1966 motorbike crash, featuring interviews with Suze Rotolo, Liam Clancy, Joan Baez, Allen Ginsberg, Dave Van Ronk, Bob Neuwirth and many others. An accompanying soundtrack was released in August 2005, which contained much previously unavailable early Dylan material. The documentary received a Peabody Award in April 2006, and a Columbia-duPont Award in January 2007.[142]

Dylan himself returned to the recording studio at some point in 2005, where he recorded "Tell Ol' Bill" for the motion picture North Country. The song is an original composition, not a cover of the similarly titled traditional folk song. The melody is based on "I Never Loved But One" by the Carter Family.

In February 2006, Dylan recorded tracks for a new album in New York City that resulted in the album Modern Times, released on August 29 2006. This date also included the iTunes Music Store release of Bob Dylan: The Collection, a digital box set containing all of his studio and live albums (773 tracks in total), along with 42 rare & unreleased tracks and a 100 page booklet. To promote the digital box set and the new album (on iTunes), Apple released a 30 second TV spot featuring Dylan, in full country & western regalia, lip-synching to "Someday Baby" against a striking white background. In a well-publicized interview to promote the album, Dylan criticised the quality of modern sound recordings and claimed that his new songs "probably sounded ten times better in the studio when we recorded 'em".[143]

Despite some coarsening of Dylan’s voice (The Guardian critic characterised his singing on the album as “a catarrhal death rattle”[144]) most reviewers gave the album high marks and many described it as the final instalment of a successful trilogy, embracing Time Out of Mind and Love and Theft.[145] Among the tracks most frequently singled out for praise were "Workingman's Blues #2" (the title was a nod to Merle Haggard's song of that name), and the final song “Ain’t Talkin’”, a nine minute talking blues in which Dylan appeared to be walking “through all-enveloping darkness, before finally disappearing into the murk”.[146] Modern Times made news by entering the U.S. charts at #1, making it Dylan's first album to reach that position since 1976's Desire, 30 years prior. At 65, Dylan became the oldest living musician to top the Billboard albums chart. The record also reached number one in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway and Switzerland.

Nominated for three Grammy Awards, Modern Times won for Best Contemporary Folk/Americana Album and Bob Dylan also won for Best Solo Rock Vocal Performance for "Someday Baby." Modern Times was ranked as the #1 album of 2006 by Rolling Stone Magazine.

In September 2006 Scott Warmuth, an Albuquerque, N.M.-based disc jockey, noted similarities between Dylan's lyrics in the album, Modern Times and the poetry of Henry Timrod, the 'Poet Laureate of the Confederacy'. A wider debate developed in The New York Times and other journals about the nature of "borrowing" within the folk process and in literature.[147][148][149][150]

May 3, 2006, was the premiere of Dylan's DJ career, hosting a weekly radio program, Theme Time Radio Hour, for XM Satellite Radio.[151][152] Each one hour show revolved around a theme such as 'Baseball', 'Tears', 'The Bible', 'Rich man/Poor man'. Among the classic and obscure records played on his show from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, Dylan has also played tracks by Blur, Prince, Billy Bragg & Wilco, Mary Gauthier and even L.L. Cool J and The Streets. BBC Radio 2 commenced transmission of Dylan's radio show in the UK on December 23, 2006, and BBC 6 Music started carrying it in January 2007. The show quickly won widespread praise from fans and critics for the way that Dylan conveyed his eclectic musical taste with panache and eccentric humor.[153][154] Each show was introduced with a few sentences spoken in a sultry voice by the actress Ellen Barkin. After 50 successful shows, a second season of Theme Time Radio Hour was commissioned to begin in September 2007.[155][156] A new original Dylan song, "Huck's Tune", written and recorded for the soundtrack to the film Lucky You, was released on April 24, 2007. Dylan commenced the 2007 installment of his "Never Ending Tour" with concert dates in Europe in the spring, followed by Canada and the USA, and performing in Australia and New Zealand in the fall.

Recent live performances and the Never Ending Tour

Dylan has played roughly 100 dates a year for the entirety of the 1990s and the 2000s, a heavier schedule than most performers who started out in the 1960s.[157][158] The "Never Ending Tour" continues, anchored by longtime bassist Tony Garnier and filled out with talented musicians better known to their peers than to their audiences. To the dismay of some fans,[159] Dylan refuses to be a nostalgia act; his reworked arrangements, evolving bands and experimental vocal approaches keep the music unpredictable night after night.

For a two and a half year period, between 2003 and 2006, Dylan ceased playing guitar, and stuck to the keyboard during concerts. Various rumors circulated as to why Dylan gave up guitar during this period, none very reliable. According to David Gates, a Newsweek reporter who interviewed Dylan in 2004, "...basically it has to do with his guitar not giving him quite the fullness of sound he was wanting at the bottom. (six strings on a guitar, ten fingers on a piano.) He's thought of hiring a keyboard player so he doesn't have to do it himself, but hasn't been able to figure out who. Most keyboard players, he says, like to be soloists, and he wants a very basic sound."[160] Dylan's touring band has two guitarists along with a multi-instrumentalist who plays steel guitar, mandolin, banjo and fiddle. From 2002 to 2005, Dylan's keyboard had a piano sound. In 2006, this was changed to an organ sound. At the start of his Spring 2007 tour in Europe, Dylan played the first half of the set on electric guitar and switched to keyboard for the second half.[161]

Dylan chooses songs from throughout his long career, seldom playing the same set twice. However most of his tours have some staple songs, in particular his biggest hits including songs such as "Like a Rolling Stone" and "All Along the Watchtower".

Dylan: His Greatest Hits

Columbia Records has now put together a 3-disc set called Dylan: His Greatest Hits. It will have his biggest hits, including "The Times They Are A-Changin'" to "Blowin' in the Wind". This big set will be released on October 1st, 2007 at midnight wherever albums are sold. The promotional trailer can be viewed on www.Dylan07.com. Dylan has not commented on the project.

Family

Dylan privately married Sara Lownds on November 22, 1965; their first child, Jesse Byron Dylan, was born on January 6 1966. Dylan and Lownds had four children in total: Jesse, Anna Lea, Samuel Isaac Abraham, and Jakob (born December 9, 1969). Dylan also adopted Sara Lownds' daughter from a prior marriage, Maria Lownds, (born October 21 1961 now married to musician Peter Himmelman). In the 1990s the youngest of his four children with Sara, Jakob Dylan, became well known as the lead singer of the band The Wallflowers. Jesse Dylan is a film director and a successful businessman. Dylan and Lownds were divorced on June 29 1977,[162] though they reportedly remained in regular contact for many years and, by some accounts, even to the present day.

In June 1986, Dylan secretly married his longtime backup singer Carolyn Dennis (often professionally known as Carol Dennis).[163] Their daughter, Desiree Gabrielle Dennis-Dylan, was born on January 31, 1986. The couple divorced in October 1992. Their marriage and child remained a closely guarded secret until the publication of Howard Sounes' Dylan biography, Down the Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan in 2001.[164]

Fan base

Bob Dylan's large and vocal fan base writes books, essays, 'zines, etc. at a furious rate. They also maintain a massive Internet presence with daily Dylan news: a site which documents every song he has ever played in concert; one that documents bootlegs that have been released; and one where visitors bet on what songs he will play on upcoming tours;[165] along with hundreds of other Dylan-themed sites. Within minutes of the end of concerts, set lists and reviews are posted by his loyal following.[166]

The poet laureate of England, Andrew Motion, is a vocal supporter of Dylan's work,[138] as are musicians Lou Reed, Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen,[167] Tom Petty, The Go-Betweens, David Bowie,[168] Mike Watt,[169] Roger Waters, Ian Hunter, David Gilmour, Nick Cave, Keith Richards, Patti Smith, Iggy Pop, Against Me!, Jack White, Ronnie Wood and Tom Waits.

The Dylan pool, which was created in 2001 has been featured on CNN, CBC, BBC, and the Associated Press. To the Associated Press, "The pool reflects both the obsessive interest Dylan still draws 40 years into his career and the way this road warrior has structured his career."Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name (see the help page). It allows interaction between fans while adding a level of competition through the unique online Bob Dylan fantasy game.

ISIS Magazine was founded in 1985 and is the longest running publication about Bob Dylan. Edited since its inception by Derek Barker, the magazine, which is published bimonthly, has subscribers in 32 countries.

Chronicles: Volume One

After a lengthy delay, October 2004 saw the publishing of Dylan's autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, with which he once again confounded expectations.[170] Dylan wrote three chapters about the year between his arrival in New York City in 1961 and recording his first album. Dylan focused on the brief period before he was a household name, while virtually ignoring the mid-1960s when his fame was at its height. Details about his motorcycle accident are limited to a few words in a single sentence. He also devoted chapters to two lesser-known albums, New Morning (1970) and Oh Mercy (1989), which contained insights into his collaborations with poet Archibald MacLeish and producer Daniel Lanois. In the New Morning chapter, Dylan expresses distaste for the "spokesman of a generation" label bestowed upon him, and evinces disgust with his more fanatical followers.

Another section features Dylan's account of a guitar-playing style in mathematical detail that he claimed was the key to his renaissance in the 1990s.[171] Despite the opacity of some passages, there is an overall clarity in voice that is generally missing in Dylan's other prose writings,[170] and a noticeable generosity towards friends and lovers of his early years.[172] At the end of the book, Dylan describes with great passion the moment when he listened to the Brecht/Weill song "Pirate Jenny", and the moment when he first heard Robert Johnson’s recordings. In these passages, Dylan suggested the process which ignited his own song writing.

Chronicles: Volume One reached number two on The New York Times' Hardcover Non-Fiction best seller list in December 2004 and was nominated for a National Book Award. Simultaneously, Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble reported the book as their number two best-seller among all categories.[173] Chronicles: Volume One is the first of three planned volumes.

Discography, film, books

Band

Dylan's 2007 touring band consists of the following musicians:

- Bob Dylan — vocals, electric guitar, keyboard, harmonica

- Tony Garnier — bass guitar, upright bass

- Stu Kimball — rhythm guitar

- Denny Freeman — lead guitar, slide guitar

- Donnie Herron - banjo, violin, pedal steel guitar

- George Recile — drums

Further reading

- Michael T. Gilmour, Tangled Up in the Bible: Bob Dylan and Scripture, Continuum, 2004, 160 pages. ISBN 0-8264-1602-0

- David Hajdu, Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Farina, and Richard Farina Farrar Straus Giroux, 2001, 328 pages. ISBN 0-374-28199-8

- Clinton Heylin, Bob Dylan: A Life In Stolen Moments, Schirmer Books, 1986, 403 pages. ISBN 0-8256-7156-6. Also known as Bob Dylan: Day By Day

- John Hinchey. Like a Complete Unknown: The Poetry of Bob Dylan’s Songs, 1961–1966. Stealing Home Press, 2002. 277 pages. ISBN 0-9723592-0-6

- Greil Marcus, The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes, Picador, 2001. ISBN 0-312-42043-9 (also published as "Invisible Republic")

- Greil Marcus, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, PublicAffairs, 2005. ISBN 1-58648-254-8

- Wilfrid Mellers, A Darker Shade Of Pale: A Backdrop To Bob Dylan Oxford University Press, 1985, 255 pages. ISBN 0-19-503622-0

- Tim Riley, Hard Rain: A Dylan Commentary, Vintage, 1992, 356 pages. ISBN 0-679-74527-0

- Anthony Varesi, The Bob Dylan Albums, Guernica Editions, 2002, 264 pages. ISBN 1-55071-139-3

- Carl Porter and Peter Vernezze (editors), Bob Dylan and Philosophy, Open Court Books, 2005, 225 pages. ISBN 0-8126-9592-5

- Webb, Stephen H. "Dylan Redeemed: From Highway 61 to Saved." Continuum Publishers. 2006

Notes

- ^ "Dylan 'reveals origin of anthem'". BBC news. 2004-04-11. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ "Dylan back on top at 65". ABC News. 2006-09-07. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "Bob Dylan by Jay Cocks". Time magazine. 1999-06-04. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ^ "Bob Dylan". Robbie Robertson. Rolling Stone Issue 946. Rolling Stone.

- ^ "Polar Music Prize, 2000". Polar Music Prize. 2000-05-01.

- ^ "Dylan Formally Launched as Candidate for Nobel Prize". Expecting Rain. 1996-10-01. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

- ^ "Dylan and the Nobel by Gordon Ball" (PDF). Journal of Oral Tradition. 2007-03-07. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ "Dylan's Words Strike Nobel Debate". CBS News. 2004-10-06. Retrieved 2006-10-17.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p.14

- ^ "Bob Dylan". Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, p.12-13

- ^ Dylan, Bob (2004). "Chronicles, Volume One". Simon & Schuster. pp. 92–93. ISBN 0306812312.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 25–33

- ^ Gill (with Kevin Odegard), Andy (2004). "A Simple Twist of Fate: Bob Dylan and the Making of Blood on the Tracks". Da Capo. p. 99. ISBN 0743230760.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 38–39.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 29–37

- ^ "Early Zimmerman bands in 1950s including 1957 photo". Expecting Rain. 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 39–43.

- ^ "Gunnn, Elston". Expecting Rain. 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 26–27.

- ^ Playboy interview with Bob Dylan, March 1978

- ^ Romancing the Clock, Marvin Karlins; Chapter 4, page 30

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 65–82

- ^ a b No Direction Home. Paramount Pictures. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Released July 21 2005.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Vol. 1, 78–79.

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Vol. 1, 250–252.

- ^ "American Masters (2006 Season) — "No Direction Home: Bob Dylan" Timeline". Thirteen WNET New York. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ Shelton, Robert (1961-09-29). "BOB DYLAN: A DISTINCTIVE STYLIST". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. [1], "allmusic". Accessed June 30 2007.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 138–142

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 156

- ^ Scaduto, Bob Dylan, 35

- ^ Mojo magazine, December 1993

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 101–103

- ^ Ricks, Dylan's Visions of Sin, 329–44.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 108–111

- ^ http://www.n-b-u.de/show_hamburg.htm Bob Dylan in Hamburg Germany

- ^ http://www.filmzentrale.com/rezis/nodirectionhomeub.htm No Direction Home: Bob Dylan

- ^ Joan Baez entry, Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 28–31

- ^ Dylan performed Only a Pawn in Their Game and When the Ship Comes In

- ^ "Dylan in the Madhouse". Retrieved 2006-08-04.

{{cite news}}: Text "BBC News" ignored (help); Text "date 2006-04-23" ignored (help) - ^ Ricks, Dylan's Visions of Sin, 221–233

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 200–205

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 160–161 Ramblin' Jack Elliott sang harmony on the Another Side of Bob Dylan version of Mr. Tambourine Man.

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 267–271, 288–291

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 178–181

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 181–182

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, 68–69

- ^ Marqusee, Wicked Messenger, 144

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 208–216

- ^ Shelton, No Direction Home, 305–314

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 186

- ^ Georgina Boyes: The Imagined Village: Culture, ideology and the English Folk Revival

- ^ Greil Marcus: The Old, Weird America, 28

- ^ Alan Jacobs: “The Songs Are My Lexicon” http://www.bobdylan.com/etc/ajacobs.html

- ^ Nat Hentoff, quoted in The Playboy Interview, March 1966; quoted in the Ralph J. Gleason interview, Ramparts, March 1966

- ^ "Like a Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, 93–95

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 189–90

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 238–243

- ^ Gill, My Back Pages, 95

- ^ Marqusee, Wicked Messenger, 139

- ^ Dylan's dialogue with the Manchester audience is recorded (with subtitles) in Scorsese's documentary No Direction Home.

- ^ ""The Bob Dylan Motorcycle-Crash Mystery"". American Heritage. 2006-07-29. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 222–5

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 282–288

- ^ Biograph (album), 1985, Liner notes & text by Cameron Crowe.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 248–253

- ^ "The Ginsberg/Dylan sessions". University of Oslo. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ "Vomit Express". Dylanchords. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ "Bob Dylan cover versions". Bjorner.com. 2002-04-16. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 273–74

- ^ "Log of performances of Forever Young". Bjorner's Still on the Road. August 20, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 358

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 368–383

- ^ "Bob Dylan". Salon.com. May 5, 2001. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 368–387

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 59–61

- ^ "Log of every performance of Hurricane". Bjorner's Still on the Road. August 20, 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 579

- ^ Shepard, Rolling Thunder Logbook, 2–49

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 386–401

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 408

- ^ Maslin, Janet (Jaunary 22, 1978). "Renaldo and Clara Film by Bob Dylan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-08-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 313

- ^ "Last Waltz, The (re-release)". MetaCritic.com. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 643

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 480–1

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 323–337, Interview with Assistant Pastor Bill Dwyer, Vineyard Church

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 490–526, Interview with Pastor Kenn Gulliksen, Vineyard Church

- ^ "Karen Hughes interview with Bob Dylan". The Dominion (NZ). 2 August 1980.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 494

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 76–80

- ^ "Extract from interview with Pastor Larry Myers". Interview from On The Tracks, Issue No.4, Fall 1994. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ "Still On The Road, 1980 Second Gospel Tour". Jaunary 25, 1980. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cott (ed.), Dylan on Dylan: The Essential Interviews, 279–285

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 334–6

- ^ "'Serve Yourself' - Reply song to Bob Dylan". John Lennon Museum.

- ^ Stephen, Holden (1981-10-29). "Rock: Dylan, in Jersey, Revises Old Standbys". The New York Times. p. c19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Slow Train Coming". Rolling Stone. 1979-09-20. Retrieved 2006-09-11.

- ^ Kawowski, Arthur (2001-09-01). "Bob Dylan's Dilemma: Which blonde". Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ^ Fishkoff, The Rebbe's Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch , 167

- ^ Pareles, Jon (1997-09-28). "A Wiser Voice Blowin' In the Autumn Wind". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Shmais, News Service (2005-10-13). "Bob Dylan @ Yom Kippur davening with Chabad in Long Island". Shmais News Service.

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 215–221

- ^ Gray, Song & Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan, 11–14

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 56–59

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 354–6

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 365–7

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 63

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Vol. 1, 219

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 599–604

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 387–8

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 515

- ^ Dylan, Chronicles, Vol. 1, 145–221

- ^ "Lyrics to 'Ring Them Bells'". Bob Dylan.com. Retrieved 2007-06-24.

- ^ Ricks, Dylan's Visions of Sin, 413–20

- ^ "Biography of Carolyn Dennis". IMDb.com. Retrieved 2006-09-06.

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 391

- ^ .[2]

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 423

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 408–9

- ^ Heylin, Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited, 693

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 420

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 426

- ^ Sounes, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, 426–9

- ^ "Remarks by the President at Kennedy Center Honors Reception". Clinton White House. 1997-12-7. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Paradise Cove (1999)". IMDb. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ^ "Oscar observed in Stuttgart, April 20,2007". Bob Links. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Gray, The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, 556–7

- ^ ""Love and Theft"". MetaCritic.com. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ ""Love and Theft"". Entertainment Weekly. 2001-10-01. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ "Intelligence Data: Bob Dylan's Love & Theft". The Village Voice. 2001-10-01. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ "Did Bob Dylan Lift Lines From Dr Saga?". Wall Street Journal. 2003-07-08. Retrieved 2006-09-22.

- ^ "Full Cast and Crew for Masked and Anonymous". IMDB. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ "Masked & Anonymous". Metacritic.com. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ "Masked & Anonymous". The New Yorker. 2003-07-24. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Motion, Andrew. "Masked and Anonymous". Sony Classics. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ "Dylan receives honorary degree". BBC News. 2004-06-23. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ^ "I'm Not There (2007)". IMDb. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ "No Direction Home: Bob Dylan A Martin Scorsese Picture". PBS. Retrieved 2006-08-04.

- ^ "Columbia-duPont Award Winners, 2007". The Journalism School, Columbia University. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ "The Genius of Bob Dylan". Rolling Stone. 2006-08-21. Retrieved 2006-09-11.

- ^ "Bob Dylan's "Modern Times"". The Guardian. 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ ""Modern Times"". Metacritic. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ^ John Harris, Mojo magazine, October 2006, p 94

- ^ ""Who's This Guy Dylan Who's Borrowing Lines From Henry Timrod?"". The New York Times. 2006-09-14. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ^ ""The Ballad of Henry Timrod". The New York Times. 2006-09-17. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ^ ""The Answer, My Friend, Is Borrowin' ... (3 Letters)". The New York Times. 2006-09-20. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

- ^ "Bob Dylan: Henry Timrod Revisited". The Poetry Foundation. 2006-10-10. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ^ "XM Theme Time Radio Hour". XM Satellite Radio. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- ^ "Theme Time Radio playlists". Not Dark Yet. Retrieved 2006-10-18.