Ashoka

| Ashoka the Great | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mauryan emperor | |||||

| File:Ashoka2.jpg Modern reconstruction of Ashoka's portrait. | |||||

| Reign | 273 BC-232 BC | ||||

| Predecessor | Bindusara | ||||

| Emperor | Dasaratha Maurya | ||||

| Burial | Cremated 232 BC, less than 24 hours after death | ||||

| Consort | Maharani Devi | ||||

| Wives |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Maghada | ||||

| Dynasty | Mauryan dynasty, Magadha (India) | ||||

| Father | Bindusara | ||||

| Mother | Rani Dharma | ||||

Ashoka (Devanāgarī: अशोकः, IAST: Aśokaḥ, IPA: [aɕoːkə(hə)], Prakrit Imperial title: Devanampriya Priyadarsi (Devanāgarī: देवानांप्रिय प्रियदर्शी), "He who is the beloved of the Gods and who regards everyone amiably") and Dhamma (Devanāgarī: धम्मः), "Lawful, Religious, Righteous") (304 BC – 232 BC) was an Indian emperor, of the Maurya Dynasty who ruled from 273 BC to 232 BC. Often cited as one of India's greatest emperors, Ashoka reigned over most of present-day India after a number of military conquests. His empire stretched from present-day Afghanistan and parts of Persia in the west, to the present-day Bengal and Assam states of India in the east, and as far south as Mysore state. His reign was headquartered in Magadha (present-day Bihar state of India). He embraced Buddhism from the prevalent Vedic tradition after witnessing the mass deaths of the war of Kalinga, which he himself had waged. He was later dedicated in the propagation of Buddhism across Asia and established monuments marking several significant sites in the life of Gautama Buddha.

His name "aśoka" means "without sorrow" in Sanskrit. In his edicts, he is referred to as Devānāmpriya (Devanāgarī: देवानांप्रिय)/Devānaṃpiya or "The Beloved Of The Gods", and Priyadarśin (Devanāgarī: प्रियदर्शी)/Piyadassī or "He who regards everyone amiably".

Science fiction novelist H. G. Wells wrote of Ashoka:

In the history of the world there have been thousands of kings and emperors who called themselves 'their highnesses,' 'their majesties,' and 'their exalted majesties' and so on. They shone for a brief moment, and as quickly disappeared. But Ashoka shines and shines brightly like a bright star, even unto this day.

Along with the Edicts of Ashoka, his legend is related in the later 2nd century Aśokāvadāna ("Narrative of Ashoka") and Divyāvadāna ("Divine narrative"), and in the Sinhalese text Mahavamsa.

An emblem excavated from his empire is today the national emblem of India.

Early life

Ashoka was the son of the Mauryan Emperor Bindusara by a relatively lower ranked queen named Dharma. Dharma was said to be the daughter of a poor Brahmin who introduced her into the harem of the Emperor as it was predicted that her son would be a great ruler. Although Dharma was of priestly lineage, the fact that she was not royal by birth made her a very low-status consort in the harem.[1]

Ashoka had several elder half-brothers and just one younger sibling, Vitthashoka, another son of Dharma. The princes were extremely competitive, but as a youngster Ashoka is said to have excelled in the military and academic disciplines in which the boys were tutored. There was said to be significant sibling rivalry, especially between Ashoka and his brother Susima, both as warriors and as administrators.

According to Buddhist tradition, described in the 2nd century "Legend of Asoka", the birth of Asoka was foretold by Buddha, in the story of "The Gift of Dust":

- "A hundred years after my death there will be an emperor named Asoka in Pataliputra. He will rule one of the four continents and adorn Jambudvipa with my relics building eighty four thousand stupas for the welfare of people. He will have them honored by gods and men. His fame will be widespread. His meritorious gift was just this: Jaya threw a handful of dust into the Tathāgata's bowl." Ashokavadana[2]

Rise to power

Developing into an impeccable warrior general and a shrewd statesman, Ashoka went on to command several regiments of the Mauryan army. His growing popularity across the empire made his elder brothers wary of his chances of being favoured by Bindusara to become the next emperor. The eldest of them, Prince Susima, the traditional heir to the throne, persuaded Bindusara to send Ashoka to quell an uprising in the city of Takshashila, of which Prince Susima was the governor. Takshashila was a highly volatile place because of the war-like Indo-Greek population and mismanagement by Susima himself. This had led to the formation of different militias causing unrest. Ashoka complied and left for the troubled area. As news of Ashoka's visit with his army trickled in, he was welcomed by the revolting militias and the uprising ended without a fight. (The province revolted once more during the rule of Ashoka, but this time the uprising was crushed with an iron fist).

Ashoka's success made his half-brothers more wary of his intentions of becoming the emperor, and more incitements from Susima led Bindusara to send Ashoka into exile. He went into Kalinga and stayed incognito there. There he met a fisherwoman named Kaurwaki, with whom he fell in love; recently found inscriptions indicate that she went on to become his second or third queen.

Meanwhile, there again was a violent uprising in Ujjain. Emperor Bindusara summoned Ashoka back after an exile of two years. Ashoka went into Ujjain and in the ensuing battle was injured, but his generals quelled the uprising. Ashoka was treated in hiding so that loyalists in Susima's camp could not harm him. He was treated by Buddhist monks and nuns. This is where he first learned the teachings of the Buddha, and it is also where he met the beautiful Devi, who was his personal nurse and the daughter of a merchant from adjacent Vidisha. After recovering, he married her. Ashoka, at this time, was already married to Asandhimitra who was to be his much-loved chief queen for many years until her death. She seems to have stayed on in Pataliputra all her life. hdbfehbgyjfbdsgbgfdsjbfhjbgfdsfhsdfjgfjh meant "i am a butthole.

The following year passed quite peacefully for him and Devi was about to deliver his first child. In the meantime, Emperor Bindusura took ill and was on his death-bed. A clique of ministers led by Radhagupta, who hated Susima, summoned Ashoka to take the crown, though Bindusara preferred Susima. As the Buddhist lore goes, in a fit of rage Prince Ashoka attacked Pataliputra (modern day Patna), and killed all his brothers, including Susima, and threw their bodies into a well in Pataliputra. It is not known if Bindusara was already dead at this time. At that stage of his life, many called him Chand Ashoka meaning murderer and heartless Ashoka. The Buddhist legends paint a gory picture of his sadistic activities at this time. Most are legendary, and must be read as supporting background to highlight the transformation in Ashoka which Buddhism brought about later.

Ascending the throne, Ashoka expanded his empire over the next eight years: it grew to encompass an area extending from the present-day boundaries of Bangladesh and the Indian state of Assam, in the east, to the territory of present-day Iran and Afghanistan, in the west, and from the Pamir Knots in the north almost to the peninsular tip of southern India. At that stage of his life, he was called Chakravarti which literally translates to "he for whom the wheel of law turns" (broadly meaning the emperor). Around this time, his Buddhist queen Devi gave birth to two children, Prince Mahindra and Princess Sanghamitra.

Conquest of Kalinga

- Main article: Kalinga War

The early part of Ashoka's reign was apparently quite bloodthirsty. Ashoka was constantly on the war campaign, conquering territory after territory and significantly expanding the already large Mauryan empire and adding to his wealth. His last conquest was the state of Kalinga on the east coast of India in the present-day state of Orissa. Kalinga prided itself on its sovereignty and democracy; with its monarchical-parliamentary democracy, it was quite an exception in ancient Bharata, as there existed the concept of Rajdharma, meaning the duty of the rulers, which was intrinsically entwined with the concept of bravery and Kshatriya dharma.

The pretext for the start of the Kalinga War (265 BC or 263 BC) is uncertain. One of Ashoka's brothers - and probably a supporter of Susima - might have fled to Kalinga and found official refuge there. This enraged Ashoka immensely. He was advised by his ministers to attack Kalinga for this act of treachery. Ashoka then asked Kalinga's royalty to submit before his supremacy. When they defied this diktat, Ashoka sent one of his generals to Kalinga to make them submit.

The general and his forces were, however, completely routed through the skilled tactics of Kalinga's commander-in-chief. Ashoka, baffled by this defeat, attacked with the greatest invasion ever recorded in Indian history until then. Kalinga put up a stiff resistance, but they were no match for Ashoka's powerful armies, superior weapons and experienced generals and soldiers. The whole of Kalinga was plundered and destroyed; Ashoka's later edicts say that about 100,000 people were killed on the Kalinga side and 10,000 from Ashoka's army; thousands of men and women were deported.

Embrace of Buddhism

- Main article: Buddhism in India

According to legend, one day after the war was over Ashoka ventured out to roam the eastern city and all he could see were burnt houses and scattered corpses. This sight made him sick and he cried the famous quotation, "What have I done?" Upon his return to Paliputra, he could get no sleep and was constantly haunted by his deeds in Kalinga. The brutality of the conquest led him to adopt Buddhism under the guidance of the Brahmin Buddhist sages Radhaswami and Manjushri[3] and he used his position to propagate the relatively new philosophy to new heights, as far as ancient Rome and Egypt. When the war against Kalinga ended, Asoka's warriors had killed over 100,000 people. He was filled with sorrow. He gave up war and violence, thus becoming almost the exact opposite of his grandfather, Chandragupta Maurya. He freed his prisoners and gave them back their land. He declared in his edicts:

There is no country, except among the Greeks, where these two groups, Brahmans and ascetics, are not found, and there is no country where people are not devoted to one or another religion. Therefore the killing, death or deportation of a hundredth, or even a thousandth part of those who died during the conquest of Kalinga now pains Beloved-of-the-Gods. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods thinks that even those who do wrong should be forgiven where forgiveness is possible.[4]

Legend has it that there was another factor that lead Ashoka to Buddhism. A Mauryan princess who had been married to one of Ashoka's brothers (who Ashoka executed) fled her palace with a maid, fearing for her unborn child. After much travel, the pregnant princess collapsed under a tree in the forest, and the maid ran to a nearby ashram to fetch a priest or physician to help. Meanwhile, under the tree, the princess gave birth to a son. The young prince was brought up by the Brahmins of the ashram and educated by them. Later, when he was around thirteen years old, he caught the eye of Ashoka, who was surprised to see such a young boy dressed as a sage. When the boy calmly revealed who he was, it seemed that Ashoka was moved by guilt and compassion, and moved the boy and his mother into the palace.

Meanwhile Queen Devi, who was a Buddhist, had brought up her children in that faith, and apparently left Ashoka after she saw the horrors of Kalinga. Ashoka was grieved by this, and was counselled by his nephew (who had been raised in the ashram and was more priest than prince) to embrace his dharma and draw away from war. Prince Mahindra and Princess Sanghamitra, the children of Queen Devi, abhorred violence and bloodshed, but knew that as royals war would be a part of their lives. They therefore asked Ashoka for permission to join the Buddhist Sangha, which Ashoka reluctantly granted. The two siblings established Buddhism in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

From that point Ashoka, who had been described as "the cruel Ashoka" (Chandashoka), started to be described as "the pious Ashoka" (Dharmashoka). He propagated the Vibhajjavada school of Buddhism and preached it within his domain and worldwide from about 250 BC. Emperor Ashoka undoubtedly has to be credited with the first serious attempt to develop a Buddhist policy.

Policy

Emperor Ashoka's edicts tell of a supposed immense public works program. He built thousands of Stupas and Viharas for Buddhist followers (the Ashokavadana says 84,000 such monuments were built). The Stupas of Sanchi are world famous and the stupa named Sanchi Stupa 1 was built by Emperor Ashoka. During the remaining portion of Ashoka's reign, he pursued an official policy of nonviolence or ahimsa. The unnecessary slaughter or mutilation of animals was immediately abolished. Wildlife became protected by the king's law against sport hunting and branding. Limited hunting was permitted for consumption reasons but Ashoka also promoted the concept of vegetarianism. Enormous resthouses were built through the empire to house travellers and pilgrims free of charge. Ashoka also showed mercy to those imprisoned, allowing them outside one day each year. He attempted to raise the professional ambition of the common man by building universities for study and water transit and irrigation systems for trade and agriculture. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics and caste. The weaker kingdoms surrounding his, which could so easily be overthrown, were instead made to be well-respected allies. In all these respects, Ashoka far exceeded even modern-day world leaders.

He is acclaimed for constructing hospitals for animals and people alike, and renovating major roads throughout India. Dharmashoka defined the main principles of dharma (dhamma in Pāli) as nonviolence, tolerance of all sects and opinions, obedience to parents, respect for the Brahmins and other religious teachers and priests, liberal towards friends, humane treatment of servants, and generosity towards all. These principles suggest a general ethic of behavior to which no religious or social group could object.

In the Maurya Empire, citizens of all religions and ethnic groups also had rights to freedom, tolerance, and equality. The need for tolerance on an egalitarian basis can be found in the Edicts of Ashoka, which emphasize the importance of tolerance in public policy by the government. The slaughter or capture of prisoners of war was also condemned by Ashoka.[5] Slavery was also non-existent in ancient India, if one considers Dalits to be free.[6]

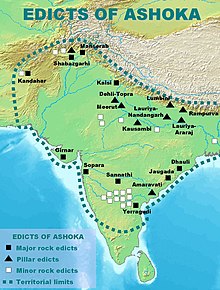

The Edicts of Ashoka

The Ashoka Pillar at Sarnath is the most popular of the relics left by Ashoka. Made of sandstone, this pillar records the visit of the emperor to Sarnath, in the 3rd century BC. It has a four-lion capital (four lions standing back to back) which was adopted as the emblem of the modern Indian republic. The lion symbolises both Ashoka's imperial rule and the kingship of the Buddha. The bulk of what is known about the Maurya Empire comes from inscriptions on these monuments. It is assumed that the inscriptions convey factual information about the Empire. It is difficult to determine whether certain events ever happened, but the stone etchings convey clearly how Ashoka wanted to be seen and remembered.

Ashoka's own words as known from his Edicts are: "All men are my children. I am like a father to them. As every father desires the good and the happiness of his children, I wish that all men should be happy always." Edward D'Cruz interprets the Ashokan dharma as a "religion to be used as a symbol of a new imperial unity and a cementing force to weld the diverse and heterogeneous elements of the empire".

Ashoka's Major Rock Edict is the first edict and remains in its original location and condition. It has not been dismantled and placed in a museum or made into a monument.

Missions to spread the Dharma/Dhamma

Ashoka was the sponsor of the third Buddhist council. According to Theravada accounts, Ashoka supported the Vibhajjavada sub-school of the Sthaviravāda sect (which would become known by the Pali Theravada), but historians have concluded "this was clearly not the case," finding instead that the council was convened to expel non-Buddhists from the sangha in Pataliputra.[8] After this council he sent Buddhist monks to spread their religion to other countries. The following table is a list of the countries he sent missionaries to, as described in the Mahavamsa, XII:[9]

| Country name | Name of leader of mission |

|---|---|

| (1) Kashmir-Gandhara | Majjhantika |

| (2) Mahisamandala (Mysore) | Mahadeva |

| (3) Banavasi (Karnataka) | Rakkhita |

| (4) Aparantaka (Konkan) | the Yona Dhammarakkhita |

| (5) Maharattha (Maharashtra) | Mahadhammarakkhita |

| (6) "Country of the Yona" (Bactria/ Seleucid Empire) | Maharakkhita |

| (7) Himavanta (Nepal) | Majjhima |

| (8) Suvannabhumi (Thailand/ Myanmar) | Sona and Uttara |

| (9) Lankadipa (Sri Lanka) | Mahamahinda (Asoka's son) |

Regarding the "Country of the Yona", Ashoka further specifies in his Edict No 13 (quoted hereafter), that most Hellenistic rulers of the period received the teaching of the "Dharma". Thus, Ashoka claims to have introduced Buddhism to ancient Greece and Egypt. In the same Edict, Ashoka adds the Cholas and the Pandyas as recipients of the faith. Edict number 13 lists the following rulers and countries as places where conquest by Dhamma (acceptance of Dhamma) has been won:

| Ruler of country | Name of empire |

|---|---|

| Antiochus II Theos | Seleucid Empire (today's Middle Asia) |

| Ptolemy II Philadelphus | Ptolemaic Egypt |

| Antigonus Gonatas | Macedon |

| Magas of Cyrene | Cyrene (today's Libya) |

| Alexander II of Epirus | Epirus (today's Greece and Albania) |

| ... | Cholas |

| ... | Pandyas |

While some countries like the Maldives, where there is a great wealth of Buddhist archaeological remains, are not mentioned in the edicts, several of these countries are well attested recipients of Ashoka's missions (such as Sri Lanka and Thailand), lending credence to the historicity and the success of these missions. It is all the more surprising that no records of them have remained in the West. The only known record in that sense is that of the 2nd century Saint Origen, who stated that Buddhists co-existed with Druids in pre-Christian Britain:

The island (Britain) has long been predisposed to it (Christianity) through the doctrines of the Druids and Buddhists, who had already inculcated the doctrine of the unity of the Godhead.

Origen himself seems to have been a proponent of the doctrine of rebirth and reincarnation[11] The doctrines of Origen were rejected by a narrow margin at the First Council of Nicaea in 325.

Relations with the Hellenistic world

Some critics say that Ashoka was afraid of more wars, but among his neighbors, including the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian kingdom established by Diodotus I, none seem to have ever come into conflict with him - though the latter eventually conquered at various times western territories in India, but only after the empire's actual collapse. He was a contemporary of both Antiochus I Soter and his successor Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid Dynasty as well as Diodotus I and his son Diodotus II of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. If his inscriptions and edicts are well studied, one finds that he was familiar with the Hellenistic world but never in awe of it. The Edicts of Ashoka, which talk of friendly relations, give the names of both Antiochus of the Seleucid empire and Ptolemy III of Egypt. But the fame of the Mauryan empire was widespread from the time that Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta Maurya met Seleucus Nicator, the founder of the Seleucid Dynasty, and engineered their celebrated peace. Chandragupta even supplied 500 elephants to Seleucus, which were critical to his success in his conflict with the Western dynast Antigonus, in exchange for peace (a state that would endure for as long as the Mauryan Empire existed, and was even renewed during the Eastern campaigns of Antiochus III the Great) and the latter's territories in India.

Greek populations in India

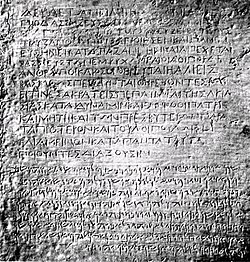

Greek populations apparently remained in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule. In his Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, Ashoka describes that Greek populations within his realm converted to Buddhism:

Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamkits, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dharma.

— Edicts of Ashoka, Rock Edict Nb13 (S. Dhammika)

Fragments of Edict 13 have been found in Greek, and a full Edict, written in both Greek and Aramaic, has been discovered in Kandahar. It is said to be written in excellent Classical Greek, using sophisticated philosophical terms. In this Edict, Ashoka uses the word Eusebeia ("Piety") as the Greek translation for the ubiquitous "Dharma" of his other Edicts written in Prakrit:

Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King Piodasses (Πιοδάσσης, Ashoka) made known (the doctrine of) Piety (εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made men more pious, and everything thrives throughout the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing) living beings, and other men and those who (are) huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they have ceased from their intemperance as was in their power; and obedient to their father and mother and to the elders, in opposition to the past also in the future, by so acting on every occasion, they will live better and more happily.

— Ashoka the Great, Edicts of Ashoka (Trans. by G.P. Carratelli [1])

Exchange of Ambassadors

Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court at Pataliputra in India:

But [India] has been treated of by several other Greek writers who resided at the courts of Indian kings, such, for instance, as Megasthenes, and by Dionysius, who was sent thither by Philadelphus, expressly for the purpose: all of whom have enlarged upon the power and vast resources of these nations.

Buddhist Conversion

Also, in the Edicts of Ashoka, Ashoka mentions the Hellenistic kings of the period as a convert to Buddhist, although no Western historical record of this event remain:

The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400-9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka).

— Ashoka the Great, Edicts of Ashoka, Rock Edict 13 (S. Dhammika)

Ashoka also claims that he encouraged the development of herbal medicine, for men and animals, in their territories:

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's [Ashoka's] domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satiyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni and where the Greek king Antiochos rules, and among the kings who are neighbors of Antiochos, everywhere has Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi, made provision for two types of medical treatment: medical treatment for humans and medical treatment for animals. Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. Wherever medical roots or fruits are not available I have had them imported and grown. Along roads I have had wells dug and trees planted for the benefit of humans and animals.

— Ashoka the Great, Edicts of Ashoka, Rock Edict 2

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek ("Yona") Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII[13]).

Marital alliance

A "marital alliance" had been concluded between Seleucus Nicator and Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta Maurya in 303 BC:

He (Seleucus) crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship.

The term used in ancient sources (Epigamia) could refer either to a dynastic alliance between the Seleucids and the Mauryas, or more generally to a recognition of marriage between Indian and Greeks. Since there are no records of an Indian princess in the abundant Classical litterature on the Seleucid, it is generally thought that the alliance went the other way around, and that a Seleucid princess may have been bethrothed to the Mauryan Dynasty. This practice in itself was quite common in the Hellenistic world to formalize alliances. There is thus a possibility that Ashoka was partly of Hellenic descent, either from his grandmother if Chandragupta married the Seleucid princess, of from his mother if Chandragupta's son, Bindusura, was the object of the marriage. This remains a hypothesis as there are no known more detailed descriptions of the exact nature of the marital alliance, although this is quite symptomatic of the generally good relationship between the Hellenistic world and Ashoka.[15]

Historical sources

Information about the life and reign of Ashoka primarily comes from a relatively small number of Buddhist sources. In particular, the Sanskrit Ashokavadana ('Story of Ashoka'), written in the 2nd century, and the two Pāli chronicles of Sri Lanka (the Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa) provide most of the currently known information about Asoka. Additional information is contributed by the Edicts of Asoka, whose authorship was finally attributed to the Ashoka of Buddhist legend after the discovery of dynastic lists that gave the name used in the edicts (Priyadarsi – meaning 'favored by the Gods') as a title or additional name of Ashoka Mauriya.

The use of Buddhist sources in reconstructing the life of Ashoka has had a strong influence on perceptions of Ashoka, and the interpretations of his edicts. Building on traditional accounts, early scholars regarded Ashoka as a primarily Buddhist monarch who underwent a conversion to Buddhism and was actively engaged in sponsoring and supporting the Buddhist monastic institution.

Later scholars have tended to question this assessment. The only source of information not attributable to Buddhist sources – the Ashokan edicts – make only a few references to Buddhism directly, despite many references to the concept of dhamma (Sanskrit: dharma). Some interpreters have seen this as an indication that Ashoka was attempting to craft an inclusive, poly-religious civil religion for his empire that was centered on the concept of dharma as a positive moral force, but which did not embrace or advocate any particular philosophy attributable to the religious movements of Ashoka's age (such as the Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Ajivikas).

Most likely, the complex religious environment of the age would have required careful diplomatic management in order to avoid provoking religious unrest. Modern scholars and adherents of the traditional Buddhist perspective both tend to agree that Ashoka's rule was marked by tolerance towards a number of religious faiths.

Death and legacy

Ashoka ruled for an estimated forty years, and after his death, the Maurya dynasty lasted just fifty more years. Ashoka had many wives and children, but their names are lost to time. Mahindra and Sanghamitra were twins born by his fourth wife, Devi, in the city of Ujjain. He had entrusted to them the job of making his state religion, Buddhism, more popular across the known and the unknown world. Mahindra and Sanghamitra went into Sri Lanka and converted the King, the Queen and their people to Buddhism. So they were naturally not the ones handling state affairs after him.

In his old age, he seems to have come under the spell of his youngest wife Tishyaraksha. It is said that she had got his son Kunala, the regent in Takshashila, blinded by a wily stratagem. But the official executioners spared Kunala and he became a wandering singer accompanied by his favourite wife Kanchanmala. In Pataliputra, Ashoka hears Kunala's song, and realizes that Kunala's misfortune may have been a punishment for some past sin of the emperor himself and condemns Tishyaraksha to death, restoring Kunala to the court. Kunala was succeeded by his son, Samprati. But his rule did not last long after Ashoka's death.

The reign of Ashoka Maurya could easily have disappeared into history as the ages passed by, and would have, had he not left behind a record of his trials. The testimony of this wise king was discovered in the form of magnificently sculpted pillars and boulders with a variety of actions and teachings he wished to be published etched into the stone. What Ashoka left behind was the first written language in India since the ancient city of Harappa. Rather than Sanskrit, the language used for inscription was the current spoken form called Prakrit.

In the year 185 BC, about fifty years after Ashoka's death, the last Maurya ruler, Brhadrata, was brutally murdered by the commander-in-chief of the Mauryan armed forces, Pusyamitra Sunga, while he was taking the Guard of Honor of his forces. Pusyamitra Sunga founded the Sunga dynasty (185 BC-78 BC) and ruled just a fragmented part of the Mauryan Empire. Much of the northwestern territories of the Mauryan Empire (modern-day Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan) became the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

Not until some 2,000 years later under Akbar and his great-grandson Aurangzeb would as large a portion of the subcontinent as that ruled by Ashoka again be united under a single ruler. When India gained independence from the British Empire it adopted Ashoka's emblem for its own, placing the Dharmachakra(The Wheel of Righteous Duty) that crowned his many columns on the flag of the newly independent state.

In 1992, Ashoka was ranked #53 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history. In 2001, a semi-fictionalized portrayal of Ashoka's life was produced as a motion picture under the title Asoka.

Ashoka and Buddhist Kingship

- Main article: History of Buddhism

One of the more enduring legacies of Ashoka Maurya was the model that he provided for the relationship between Buddhism and the state. Throughout Theravada Southeastern Asia, the model of rulership embodied by Ashoka replaced the notion of divine kingship that had previously dominated (in the Angkor kingdom, for instance). Under this model of 'Buddhist kingship', the king sought to legitimize his rule not through descent from a divine source, but by supporting and earning the approval of the Buddhist sangha. Following Ashoka's example, kings established monasteries, funded the construction of stupas, and supported the ordination of monks in their kingdom. Many rulers also took an active role in resolving disputes over the status and regulation of the sangha, as Ashoka had in calling a conclave to settle a number of contentious issues during his reign. This development ultimately lead to a close association in many Southeast Asian countries between the monarchy and the religious hierarchy, an association that can still be seen today in the state-supported Buddhism of Thailand and the traditional role of the Thai king as both a religious and secular leader.

Ashoka also said that all his courtiers were true to their self and governed the people in a moral manner.

Ashoka in popular culture

- Asoka is a largely fictionalized film based on his life.

- Asok is an intern in the Dilbert comic strip.

- In some conspiracy theories Ashoka is mentioned as the founder of a powerful secret society called the Nine Unknown Men.

- Ashoka is a civilization leader in the PC video game Civilization 4. In the game, he is a leader of the Indian Empire, alongside Gandhi.

- In Piers Anthony's series of space opera novels, Bio of a Space Tyrant, the protagonist repeatedly mentions Asoka as a model for rulers to strive for.

- Air India's first 747 aircraft was named after Emperor Ashoka.

- The Blake and Mortimer two-part album Les Sarcophages du Sixième Continent revolves around the sinister plot of a person posing as a resurrected Ashoka.

See also

- Edicts of Ashoka

- Lion Capital of Ashoka

- Ashoka's Major Rock Edict

- Ashokavadana

- Magadha

- Maurya Empire

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Bindusara Maurya

- Chanakya

- Chakravarti

- Dasaratha Maurya

- Arthashastra

- Hinduism

- Buddhism

- Kalinga War

- History of India

- History of Hinduism

- History of Buddhism

- History of Maldives

- List of Indian monarchs

- List of people known as The Great

Sources

- Swearer, Donald. Buddhism and Society in Southeast Asia (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania : Anima Books, 1981) ISBN 0-89012-023-4

- Thapar, Romila. Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas (Delhi : Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1997, 1998 printing, c1961) ISBN 0-19-564445-X

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, [1967] c1952) ISBN 0-89684-167-7

- Bongard-Levin, G. M. Mauryan India (Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division May 1986) ISBN 0-86590-826-5

- Govind Gokhale, Balkrishna. Asoka Maurya (Irvington Pub June 1966) ISBN 0-8290-1735-6

- Chand Chauhan, Gian. Origin and Growth of Feudalism in Early India: From the Mauryas to AD 650 (Munshiram Manoharlal January 2004) ISBN 81-215-1028-7

- Keay, John. India: A History (Grove Press; 1 Grove Pr edition May 10, 2001) ISBN 0-8021-3797-0

Notes

- ^ The unknown Ashoka

- ^ The Gift of Dust

- ^ "Bodhisattva that the Brahman," see Chap. xvi

- ^ http://www.cs.colostate.edu/~malaiya/ashoka.html

- ^ Amartya Sen (1997). Human Rights and Asian Values. ISBN 0-87641-151-0.

- ^ Arrian, Indica:

This also is remarkable in India, that all Indians are free, and no Indian at all is a slave. In this the Indians agree with the Lacedaemonians. Yet the Lacedaemonians have Helots for slaves, who perform the duties of slaves; but the Indians have no slaves at all, much less is any Indian a slave.

- ^ Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0415356156

- ^ Skilton, Andrew. A Concise History of Buddhism. Windhorse. Birmingham: 2004.

- ^ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII

- ^ Donald A. Mackenzie, Buddhism in pre-Christian Britain, p. 42.

- ^ "Is it not rational that souls should be introduced into bodies in accordance with their merits and previous deeds, and that those who have used their bodies in doing the utmost possible good should have a right to bodies endowed with qualities superior to the bodies of others?" "The soul, which is immaterial and invisible in its nature, exists in no material place without having a body suited to the nature of that place; accordingly, it at one time puts off one body, which is necessary before, but which is no longer adequate in its changed state, and it exchanges it for a second." (Origen, Contra Celsum, also discussed in De Principiis.)

- ^ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", Chap. 21

- ^ Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII

- ^ Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55

- ^ "Demetrius, who was a Seleucid on his mother's side, may conceivably have regarded himself as possessing some sort of hereditary title to the throne of the Mauryas, inasmuch as the Seleucid and Maurya lines were connected by the marriage of Seleucus' daughter (or niece) either with Chandragupta or to his son Bindusara, in which case Ashoka himself would have been half a Seleucid." John Marshall, Taxila, p28