Futurism

Futurism was a 20th century art movement. Although a nascent Futurism can be seen surfacing throughout the very early years of the twentieth century, the 1907 essay Entwurf einer neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst (Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music) by the Italian composer Ferruccio Busoni is sometimes claimed as its true starting point. Futurism was a largely Italian and Russian movement, although it also had adherents in other countries, England for example.

The Futurists explored every medium of art, including painting, sculpture, poetry, theatre, music, architecture and even gastronomy. The Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was the first among them to produce a manifesto of their artistic philosophy in his Manifesto of Futurism (1909), first released in Milan and published in the French paper Le Figaro (February 20). Marinetti summed up the major principles of the Futurists, including a passionate loathing of ideas from the past, especially political and artistic traditions. He and others also espoused a love of speed, technology, and violence. Futurists dubbed the love of the past passéisme. The car, the plane, the industrial town were all legendary for the Futurists, because they represented the technological triumph of people over nature.

Futurist Painting and Sculpture in Italy 1910-1914

Marinetti's impassioned polemic immediately attracted the support of the young Milanese painters - Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, and Luigi Russolo - who wanted to extend Marinetti's ideas to the visual arts. (Russolo was also a composer, and introduced Futurist ideas into his compositions). The painters Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini met Marinetti in 1910 and together with Boccioni, Carrà and Russolo issued the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters. It was couched in the violent and declamatory language of Marinetti's founding manifesto, opening with the words,[1]

The cry of rebellion which we utter associates our ideals with those of the Futurist poets. These ideas were not invented by some aesthetic clique. They are an expression of a violent desire, which burns in the veins of every creative artist today. ... We will fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless and snobbish religion of the past, a religion encouraged by the vicious existence of museums. We rebel against that spineless worshipping of old canvases, old statues and old bric-a-brac, against everything which is filthy and worm-ridden and corroded by time. We consider the habitual contempt for everything which is young, new and burning with life to be unjust and even criminal.

They repudiated the cult of the past and all imitation, praised originality, "however daring, however violent", bore proudly "the smear of madness", dismissed art critics as useless, rebelled against harmony and good taste, swept away all the themes and subjects of all previous art, and gloried in science. Their manifesto did not contain a positive artistic programme, which they attempted to create in their subsequent Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting. The Technical Manifesto committed them to a "universal dynamism", which was to be directly represented in painting. Objects in reality were not separate from one another or from their surroundings: "The sixteen people around you in a rolling motor bus are in turn and at the same time one, ten four three; they are motionless and they change places. ... The motor bus rushes into the houses which it passes, and in their turn the houses throw themselves upon the motor bus and are blended with it." [2]

The Futurist painters were slow to develop a distinctive style and subject matter. In 1910 and 1911 they used the technique of divisionism, breaking light and color down into a field of stippled dots and stripes, which had been originally created by Seurat. Severini, who lived in Paris, was the first to come into contact with Cubism and following a visit to Paris in 1911 the Futurist painters adopted the methods of the Cubists. Cubism offered them a means of analysing energy in paintings and expressing dynamism.

They often painted modern urban scenes. Carrà's Funeral of the Anarchist Galli (1910-11) is a large canvas representing events that the artist had himself been involved in in 1904. The action of a police attack and riot is rendered energetically with diagonals and broken planes. His Leaving the Theatre (1910-11) uses a divisionist technique to render isolated and faceless figures trudging home at night under street lights.

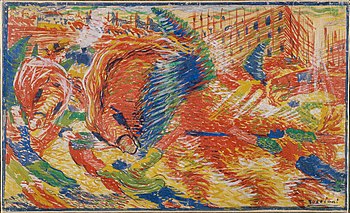

Boccioni's The City Rises (1910) represents scenes of construction and manual labour with a huge, rearing red horse in the centre foreground, which workmen struggle to control. His States of Mind, in three large panels, The Farewell, Those who Go, and Those Who Stay, "made his first great statement of Futurist painting, bringing his interests in Bergson, Cubism and the individual's complex experience of the modern world together in what has been described as one of the 'minor masterpieces' of early twentieth century painting." [3] The work attempts to convey feelings and sensations experienced in time, using new means of expression, including "lines of force", which were intended to convey the directional tendencies of objects through space, "simultaneity", which combined memories, present impressions and anticipation of future events, and "emotional ambience" in which the artist seeks by intuition to link sympathies between the exterior scene and interior emotion.[4]

Boccioni's intentions in art were strongly influenced by the ideas of Bergson, including the idea of intuition, which Bergson defined as a simple, indivisible experience of sympathy through which one is moved into the inner being of an object to grasp what is unique and ineffable within it. The Futurists aimed through their art thus to enable the viewer to apprehend the inner being of what they depicted. Boccioni developed these ideas at length in his book, Pittura scultura Futuriste: Dinamismo plastico (Futurist Painting Sculpture: Plastic Dynamism) (1914).[5]

Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912) exemplifies the Futurists' insistence that the perceived world is in constant movement. The painting depicts a dog whose legs, tail and leash - and the feet of the person walking it - have been multiplied to a blur of movement. It illustrates the precepts of the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting that, "On account of the persistency of an image upon the retina, moving objects constantly multiply themselves; their form changes like rapid vibrations, in their mad career. Thus a running horse has not four legs, but twenty, and their movements are triangular." [6] His Rhythm of the Bow (1912) similarly depicts the movements of a violinist's hand and instrument, rendered in rapid strokes within a triangular frame.

The adoption of Cubism determined the style of much subsequent Futurist painting, which Boccioni and Severini in particular continued to render in the broken colors and short brush-strokes of divisionism. But Futurist painting differed in both subject matter and treatment from the quiet and static Cubism of Picasso, Braque and Gris. Although there were Futurist portraits (e.g. Carrà's Woman with Absinthe (1911), Severini's Self-Portrait (1912), and Boccioni's Matter (1912)), it was the urban scene and vehicles in motion that typified Futurist painting - e.g. Severini's Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin (1912) and Russolo's Automobile at Speed (1913)

In 1912 and 1913, Boccioni turned to sculpture to translate into three dimensions his Futurist ideas. In Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) he attempted to realise the relationship between the object and its environment, which was central to his theory of "dynamism". The sculpture represents a striding figure, now cast in bronze and exhibited in the Tate Gallery. He explored the theme further in Synthesis of Human Dynamism (1912), Speeding Muscles (1913) and Spiral Expansion of Speeding Muscles (1913). His ideas on sculpture were published in the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture[7] In 1915 Balla also turned to sculpture making abstract "reconstructions", which were created out of various materials, were apparently moveable and even made noises. He said that, after making twenty pictures in which he had studied the velocity of automobiles, he understood that "the single plane of the canvas did not permit the suggestion of the dynamic volume of speed in depth ... I felt the need to construct the first dynamic plastic complex with iron wires, cardboard planes, cloth and tissue paper, etc." [8]

In 1914, personal quarrels and artistic differences between the Milan group, around Marinetti, Boccioni, and Balla, and the Florence group, around Carrà, Ardengo Soffici (1879-1964) and Giovanni Papini (1881-1956), created a rift in Italian Futurism. The Florence group resented the dominance of Marinetti and Boccioni, whom they accused of trying to establish "an immobile church with an infallible creed", and each group dismissed the other as passéiste.

Futurism had from the outset admired violence and was intensely patriotic. The Futurist Manifesto had declared, "We will glorify war - the world's only hygiene - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman." [9] Although it owed much of its character and some of its ideas to radical political movements, it was not much involved in politics until the autumn of 1913.[10] Then, fearing the re-election of Giolitti, Marinetti published a political manifesto. In 1914 the Futurists began to campaign actively against Austria and Italian neutrality. In September, Boccioni, seated in the balcony of the Teatro dal Verme in Milan, tore up an Austrian flag and threw it into the audience, while Marinetti waved an Italian flag.

The outbreak of war disguised the fact that Italian Futurism had come to an end. The Florence group had formally acknowledged their withdrawal from the movement by the end of 1914. Boccioni produced only one war picture and was killed in 1916. Severini painted some significant war pictures in 1915 (e.g. War, Armored Train, and Red Cross Train), but in Paris turned towards Cubism and post-war was associated with the Return to Order.

After the war, Marinetti attempted to revive the movement in il secondo Futurismo.

Cubo-Futurism

Cubo-Futurism was the main school of Russian Futurism which imbued influence of Cubism and developed in Russia in 1913.

Like their Italian predecessors, the Russian Futurists — Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksey Kruchenykh, Vladimir Mayakovsky, David Burlyuk — were fascinated with dynamism, speed, and restlessness of modern urban life. They purposely sought to arouse controversy and to attract publicity by repudiating static art of the past. The likes of Pushkin and Dostoevsky, according to them, should have been "heaved overboard from the steamship of modernity". They acknowledged no authorities whatsoever; even Marinetti, principles of whose manifesto they adopted earlier — when he arrived to Russia on a proselytizing visit in 1914 — was obstructed by most Russian Futurists who now did not profess to owe anything to him.

In contrast to Marinetti's circle, Russian Futurism was a literary rather than artistic movement. Although many leading poets (Mayakovsky, Burlyuk) dabbled in painting, their interests were primarily literary. On the other hand, such well-established artists as Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, and Kazimir Malevich found inspiration in the refreshing imagery of Futurist poems and experimented with versification themselves. The poets and painters attempted to collaborate on such innovative productions as the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, with texts by Kruchenykh and sets contributed by Malevich.

The movement began to waste away after the revolution of 1917. Many prominent members of the Russian Futurism emigrated abroad. Artists like Mayakovsky and Malevich become the prominent members of the Soviet establishment and Agitprop of the 1920s. Others like Khlebnikov were persecuted for their beliefs.

Futurism in Music

One of the many 20th century classical movements in music was one which involved homage to, inclusion of, or imitation of machines. Closely identified with the central Italian Futurist movement were brother composers Luigi Russolo and Antonio Russolo, who used instruments known as "intonarumori", which were essentially sound boxes used to create music out of noise. Other examples include Arthur Honegger's Pacific 231, which imitates the sound of a steam locomotive, Prokofiev's "The Steel Step", and the experiments of Edgard Varèse. Most notably, however, might be composer George Antheil. Embraced by dadists, futurists, and modernists alike, he was championed as the musical face of the radical movements of the 1920s. The culmination of his machine obsession, as seen in previous works such as "Airplane Sonata" and "Death of the Machines", was manifest in the 30 min. Ballet mécanique. Originally accompanied by an experimental film by Fernand Leger but scratched due to the length of the score being twice that of the film, the autograph score calls for a daring and bold percussion ensemble, consisting of 3 xylophones, 4 bass drums, a tam-tam, three airplane propellers (one large wood, one small wood, one metal), seven electric bells, a siren, 2 "live pianists", and 16 synchronized player pianos. At the time it was written however, synchronizing 16 player pianos was impossible and was performed in a reduced form (in 1999 the piece was fully realized to a great success). Antheil's piece was a first for music in synchronizing machines with human players, and in exploiting the various differences between the technical competence of humans and machines (that is to say, what machines can play vs. what people can't, and vice versa); this ideology can be seen reflected in even modern day music where the philosophy that man and machine need each other to create the best music has led to the incorporation of software into live performances. Antheil himself described his piece as a "solid shaft of steel."

Futurism in the 1920s and 1930s

Many Italian Futurists instinctively supported the rise of Fascism in Italy in the hope of modernizing the society and the economy of a country that was still torn between unfulfilled industrial revolution in the North and the rural, archaic South. Marinetti founded the Partito Politico Futurista (Futurist Political Party) in early 1918, which only a year later was absorbed into Benito Mussolini's Fasci di combattimento, making Marinetti one of the first supporters and members of the National Fascist Party. However, he opposed Fascism's later canonical exultation of existing institutions, calling them "reactionary", and, after walking out of the 1920 Fascist party congress in disgust, withdrew from politics for three years. Nevertheless, he stayed a notable force in developing the party thought throughout the regime. Some Futurists' aestheticization of violence and glorification of modern warfare as the ultimate artistic expression and their intense nationalism also induced them to embrace Fascism. Many Futurists became associated with the regime in the 1920s, which gave them both official recognition and the ability to carry out important works, especially in architecture.

Throughout the Fascist regime Marinetti sought to make Futurism the offical state art of Italy but failed to do so. Mussolini was personally uninterested in art and chose to give patronage to numerous styles and movements in order to keep artists loyal to the regime. Opening the exhibition of Novecento art in 1923 he said, "I declare that it is far from my idea to encourage anything like a state art. Art belongs to the domain of the individual. The state has only one duty: not to undermine art, to provide humane conditions for artists, to encourage them from the artistic and national point of view."[11] Mussolini's mistress, Margherita Sarfatti, who was as able a cultural entrepreneur as Marinetti, successully promoted the rival Novecento group, and even persuaded Marinetti to sit on its board. Although in the early years of Italian Fascism modern art was tolerated and even embraced, towards the end of the 1930s, right-wing Fascists introduced the concept of "degenerate art" from Germany to Italy and condemned Futurism.

Marinetti made numerous moves to ingratiate himself with the regime, becoming less radical and avant garde with each. He moved from Milan to Rome to be nearer the centre of things. He became an academician despite his condemnation of academies, married despite his condemnation of marriage, promoted religious art after the Lateran Treaty of 1929 and even reconciled himself to the Catholic church, declaring that Jesus was a Futurist.

Some leftists that came to Futurism in the earlier years continued to oppose Marinetti's artistic and political direction of Futurism. Leftists continued to be associated with Futurism right up until 1924, when the socialists, communists, anarchists and anti-Fascists finally walked out of the Milan Congress,[12], and the anti-Fascist voices in Futurism were not completely silenced until the annexation of Ethiopia and the Italo-German Pact of Steel in 1939.[13]

Futurism expanded to encompass other artistic domains. In architecture, it was characterized by a distinctive thrust towards rationalism and modernism through the use of advanced building materials. In Italy, futurist architects were often at odds with the fascist state's tendency towards Roman imperial/classical aesthetic patterns. However several interesting futurist buildings were built in the years 1920–1940, including many public buildings: stations, maritime resorts, post offices, etc. See, for example, Trento's railway station built by Angiolo Mazzoni.

Cultural Context

Society, Change and a New Age

Futurist Artists were among the first to use modern life as a theme for their works. Futurist artists demanded social change, and denounced all kinds of utilitarian morals and ethics. The early 20th century also presented itself to be a boom period in technology, and communication. The world was changing as people and scientists discovered new phenomena, while inventors were creating new and wonderful creations, which wooed audiences around the world. The machine age was born and raring to go. Artifacts of the Machine Age include:

- Mass production of high volume goods on moving assembly lines, particularly of the automobile

- Gigantic production machinery, especially for producing and working metal, such as steel rolling mills, bridge component fabrication, and automobile body presses

- Powerful earthmoving equipment

- Steel framed buildings of great height (the skyscraper)

- Radio and phonograph technology

- High speed printing presses, enabling the production of low cost newspapers and mass market magazines

- Large hydroelectric and thermal electric power production plants and distribution systems

- Low cost appliances for the mass market that employ fractional horsepower electric motors, such

Futurists thrived on the impressions of speed, noise, and machines, communications and information that had become a large part of the nineteenth-century cities. They hated the untamed, middle-class merits and tastes and more importantly; they disliked the factions of the past, like the church and monarch. Futurists had very right wing ideology, and cussed at social trends like feminism, and they were stern advocates of violence and war.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, Italy was still a relatively backward country, with half the population illiterate, and many living in poverty. The social landscape and political guise of the nation was also backward as old 19th century ways and customs were still widely employed. The Authoritarian church was still very much in power, and made sure that Italy would not assimilate into modern Europe. Marinetti was very much against all this antiquity, and wanted Italy to become a powerhouse in Europe, by setting new trends and becoming a cultural, social and economic Hub. These ideas are generated and reinforced in Futurism.

People started to think ‘outside the square’ as a new age of speed and rapid velocity was raging into history, and the Futurist movement, both hands clasped, was there to join the Ride

Styles, Schools and Movements of Modern Art

During the existence of Futurism many art styles, were in operation which shaped and influenced Futurist artists.

The creation and expansion of Modernism is the most influential movement on Futurism. Futurism is essentially a branch of Modernism. Modernist ideas started flowing in the mid to late 19th century. Like Futurism Modernism was based on the foundations, that traditional art and art practises were becoming outdated, and new forms of art were needed to compensate for the immanent change in social and technological order of the new age.

Modernism took a new trend from 1910–1930. It was in time the Russian Revolution was in full swing and WWI was close to fairing up. It was these events which shaped Modernism to be a movement associated with disruption, rejection and almost radicalism. It was these ideas that were harnessed and embraced by Futurism, thus it was the Modernist world around Marinetti which shaped and guided his manifesto. Futurism was simply an arm of the new modernist age, but a more violent and politically motivated fraction.

Around the time Futurism was invented, we also had the movement of Avant-garde artists who, little did they know it at the time, would inspire many artists and art movements. The Avant-garde artists are famous for experimenting, and discovering novel ideas about art theory and art practice. The avant-garde movement inspired the Futurist in two ways. Firstly it encouraged them and gave them the motivation to start their own art movements, and become the innovators themselves. In a time where movements and styles were all being exhibited in Paris, it was this one sidedness, which prompted the Italians to start movements of their very own.

The avant-garde movement influenced Futurists on second level, because many Futurist Artists used the styles and techniques which were being discovered in Paris at the time. So their artworks were influenced by the avant-garde artists. Giacomo Balla pursued a divisionist method of painting influenced by neo-impressionism. Futurists also experimented with the depiction of sequential movement, influenced by the photographic studies of animal and human locomotion by Eadweard Muybridge.

The other big movement to influence Futurists was Cubism. Cubism started out in 1907 just a few years before Futurism. It was the works of Picasso and Braque. In cubist artworks, objects are broken up, analyzed, and re-assembled in an abstracted form — instead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts the subject from a multitude of viewpoints to represent the subject in a greater context. These methods and techniques were not far of what Futurists employed and many argued that Futurism was just an extension of Cubism.

Finally other art movement and schools which were in operation as the same time as Futurism, and influenced or influenced by Futurists include:

- Fauvism

- Art deco

- Vorticism

- Novecento Italiano

- Jack of diamonds

However, Futurists claimed to be a movement created in a vacuum, as they wanted to remove themselves from the past.They believed they were completely uninfluenced, despite their visits to multiple art exhibitions, including that of the Cubists.

Politics and War and Turmoil

The world of Futurism was nothing short of violent and highly controversial. It was riddled with politics, ideology and religion, as decidedly turbulent times were ahead. From World War One to the highly chaotic Italian political spectrum, Futurism was right there with it all, as its painters were both split and united on varying matters at hand.

For a start Futurists were very pro-change and very nationalistic. During the First World War Italy was at a fluctuating stage, whereby new and powerful political organizations were coming to power and demanding revolt. These changes to the political spectrum did not go unnoticed by the Futurists. Many Italian Futurists instinctively supported the rise of fascism in Italy in the hope of modernizing the society and the economy of a country that was still torn between unfulfilled industrial revolution in the North and the rural, archaic South. The ‘Futurist Political party’ was formed in early 1918, and empowered the artists to further start voicing their opinion and ideology.

Politics grew further into the fabric of Futurism when the leader of the movement, Marinetti became wrapped up in fascism and developed a close friendship with one Benito Mussolini. Marinetti became one of the first supporters and members of the National Fascist Party. Fascism was a new concept at the time, and it seemed to tie in with the ideals of Futurism. Some Futurists' fetish with violence and glorification of modern warfare as the ultimate artistic expression and their intense nationalism also induced them to embrace fascism.

Futurism also had left wing communist factions. By now Futurists had expanded all over Europe, and these artists brought with them different views and ideas. Such factions included Ardito-Futurist, communist-Futurist, independent-Futurist. These factions stood firm against right wing nationalist element of the movement, and managed to survive, and instill their own beliefs.

With WWI raging across Europe, Futurist members started demonstrating on the streets in 1914–1915. These demonstrations glorified war, and they put pressure on the government to join the War. Their wish was granted and Italy joined the war in 1916. This War would lead to two prominent members being killed, Boccioni and Sant’Elia. Much of the movement's spark and creativity was lost after the death of their comrades.

In 1920’s with the end of War, and subsequent decline in Futurism, a strong rift began to emerge between the Fascists and Futurists. Marinetti and the Futurists had strong ideals opposing state authority, and totalitarianism, while the Fascists were trying to instill nation-wide rule and autocracy. Their proposals against the church and the monarch had also been declined by the Mussolini-led Fascists, who were by this stage in control of Italy.

Through the late 20s, 30s and 40s the relationship between the two factions was always fluctuating, with both conflicting interests and conversely unifying marches through Rome. A new movement was also at hand, as Apolitical Futurists started emerging. These factions were not only left wing, but were also very much against the Fascist era, and a second age of Futurism was predicted.

Eventually the fascists dropped ties with the Futurists, because of more political turmoil. World War II saw Mussolini’s regime ally with Nazi Germany. The downfall of Italy eventually followed, after their defeat at the hands of the Allies. After the Second World War, fascism was directly linked to Nazism, thus gaining a status of evil. Once the War was over all such right wing extremist stances were banned although they still continued on a small scale.

Thus the Futurists' ties with Fascism saw Futurism gain a bad name, and with the awakening of a brand new republic of Italy, all of the ‘evils’ of the early 20th century, including Futurism, was discarded and banished.

The ‘death’ of Futurism was a horrible process, and its end was multi-layered. The end of WWII and fascism, plus the hanging of Mussolini in 1945 brought the conclusion of politics for the Futurists. The end of the machine age in 1945 also meant that a lot of their flair and ideas were finished. Finally the death of Marinetti himself in 1944 ended Futurism in Italy, and so an art movement with such a turbulent, controversial yet inspiring history had come to a halt, but it would prove be a benchmark and starting block for many other movements, schools and styles.

The legacy of Futurism

Futurism influenced many other twentieth century art movements, including Art Deco, Vorticism, Constructivism, Surrealism and Dada. Futurism as a coherent and organized artistic movement is now regarded as extinct, having died out in 1944 with the death of its leader Marinetti, and Futurism was, like science fiction, in part overtaken by 'the future'.

Nonetheless the ideals of futurism remain as significant components of modern Western culture; the emphasis on youth, speed, power and technology finding expression in much of modern commercial cinema and culture. Ridley Scott consciously evoked the designs of Sant'Elia in Blade Runner. Echoes of Marinetti's thought, especially his "dreamt-of metallization of the human body", are still strongly prevalent in Japanese culture, and surface in manga/anime and the works of artists such as Shinya Tsukamoto, director of the "Tetsuo" (lit. "Ironman") films. Futurism has produced several reactions, including the literary genre of cyberpunk — in which technology was often treated with ambivalence — whilst artists who came to prominence during the first flush of the Internet, such as Stelarc, Natasha Vita-More and Mariko Mori, produce work which comments on futurist ideals. Natasha Vita-More also designed Primo Posthuman as the artistic futurists body design.

A revival of sorts of the Futurist movement began in 1988 with the creation of the Neo-Futurist style of theatre in Chicago, which utilizes Futurism's focus on speed and brevity to create a new form of immediate theatre. Currently, there are active Neo-Futurist troupes in Chicago and New York.

Another revival in the San Francisco area, perhaps best described as Post-Futurist, centers around the band Sleepytime Gorilla Museum, who took their name from a (possibly fictitious) Futurist press organization (described by founder John Kane as "the fastest museum alive") dating back to 1916. SGM's lyrics and (very in-depth) liner notes routinely quote and reference Marinetti and The Futurist Manifesto, and juxtapose them with opposing views such as those presented in Industrial Society and Its Future (also known as the Unabomber Manifesto, attributed to Theodore Kaczynski).

Prominent Futurist artists

- Giacomo Balla, painter

- Benedetta

- Umberto Boccioni , painter, sculptor

- Anton Giulio Bragaglia

- David Burliuk, painter

- Vladimir Burliuk, painter

- Mario Carli

- Carlo Carrà, painter

- Sebastiano Carta

- Ambrogio Casati, painter

- Primo Conti, artist

- Tullio Crali

- Giulio d'Anna

- Fortunato Depero, painter

- Nicolay Diugheroff

- Gerardo Dottori, painter, poet and art critic

- Fillia (Luigi Colombo), painter and writer

- Luciano Folgore

- Corrado Govoni

- Gian Pietro Lucini

- Antonio Marasco

- Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, poet

- Vladimir Mayakovsky, poet

- Angiolo Mazzoni, architect

- Sante Monachesi

- Aldo Palazzeschi, writer

- Giovanni Papini, writer

- Enrico Prampolini, painter, sculptor and stage director

- Francesco Pratella, composer

- Ugo Pozzo

- Pippo Rizzo

- Luigi Russolo, painter, musician & custom-made instrument builder

- Antonio Sant'Elia, architect

- Hugo Scheiber

- Emilio Settimelli, writer and journalist

- Gino Severini, painter

- Mario Sironi, painter

- Ardengo Soffici, painter and writer

- Tato (Guilielmo Sansoni), painter and photographer

- Ernest Thayat , sculptor and painter (born Ernesto Michaelles)

- Luigi De Giudici, painter

References

- ^ http://www.unknown.nu./futurism/painters.html

- ^ http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/techpaint.html

- ^ Humphreys, R. Futurism, Tate Gallery, 1999, p.31

- ^ ibid.

- ^ For detailed discussions of Boccioni's debt to Bergson, see Petrie, Brian, "Boccioni and Bergson", The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 116, No.852, March 1974, pp.140-147, and Antliff, Mark "The Fourth Dimension and Futurism: A Politicized Space", The Art Bulletin, December 2000, pp.720-733.

- ^ http://www.unknown.nu.futurism/techpaint.html

- ^ http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/techsculpt.html

- ^ Quoted in Martin, Marianne W. Futurist Art and Theory, Hacker Art Books, New York, 1978, p.201

- ^ http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/manifesto.html

- ^ Martin, Marianne W., p.186

- ^ Quoted in Braun, Emily, Mario Sironi and Italian Modernism: Art and Politics under Fascism, Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ^ "... Congresso Futurisa, tenuto a Milano nel novembre 1924, ottenendo di fatto l'uscita dal movimento dei socialisti, dei communisti, degli archarchici e di tutti gli altri antifascisiti qui vi avaveno militato fino a quel momento." L'aeropittura futurista www.users.libero.it/macbusc/id22.htm

- ^ Berghaus, Günther, "New Research on Futurism and its Relations with the Fascist Regime", Journal of Contemporary History, 2007, Vol. 42, p.152

See also

- Cubo-Futurism

- Future studies

- Rayonism (also as Rayonnism)

- Universal Flowering

- Neo-Futurism

- Russian futurism

- Art manifesto

- Futurist meals

Further reading

- Gentile, Emilo. 2003. The Struggle for Modernity: Nationalism, Futurism, and Fascism. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-97692-0

- I poeti futuristi, dir. by M. Albertazzi, w. essay of G. Wallace and M. Pieri, Trento, La Finestra editrice, 2004. ISBN 88-88097-82-1

- John Rodker (1927). The future of futurism. New York: E.P. Dutton & company.