Surrealism

Surrealism is a philosophy, a cultural and artistic movement, and a term used to describe unexpected juxtapositions.

- Philosophy. The philosophy of Surrealism aims for liberation of the mind by emphasizing the critical and imaginative faculties of the "unconscious mind", thus bringing about personal, cultural, political and social revolution. At various times surrealist groups aligned with communism and anarchism to advance radical political, as well as social and artistic, change.

- Cultural and artistic movement. The Surrealism movement originated in post-World War I European avant-garde literary and art circles, and many early Surrealists were associated with the earlier Dada movement. Movement participants sought to revolutionize life with actions intended to bring about change in accordance with Surrealism philosophy. While the movement's most important center was Paris, it spread throughout Europe and to North America during the course of the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Some historians mark the end of the movement at World War II, some with the death of André Breton, while others believe that Surrealism continues as an identifiable movement.

- Unexpected juxtapostion. The word "surreal" is often used to describe unexpected juxtapositions or use of non-sequiturs in art or dialog, particuarly where such juxtapositions argue for their own self-consistency. This usage is often independent of any direct connection to Surrealism the movement, and is used in both formal and informal contexts.

The term Surrealism was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire to in the program notes describing Parade (1917), a collaboration of Jean Cocteau, Erik Satie, Pablo Picasso and Léonide Massine:

- From this new alliance, for until now stage sets and costumes on one side and choreography on the other had only a sham bond between them, there has come about, in 'Parade', a kind of super-realism ('sur-réalisme'), in which I see the starting point of a series of manifestations of this new spirit ('esprit nouveau').'

Philosophy

Surrealist philosophy emerged around 1920, partly as an outgrowth of Dada, with French writer Breton as its leader.

In Breton's Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 he defines Surrealism as:

- Dictionary: SurrealISM, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, or in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

- Encyclopedia: SurrealISM. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life."

By Breton's admission, however, as well as by the subsequent developments, these definitions were capable of considerable expansion.

While Dada rejected categories and labels and was rooted in negative response to the First World War, Surrealism advocates the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. (The three Hegelian dialectical stages of development are: 1) a thesis, giving rise to its reaction, 2) an antithesis which contradicts or negates the thesis, and 3) the tension between the two being resolved by means of a synthesis.)

Surrealists diagnosis of the "problem" of the realism and capitalist civilisation is a restrictive overlay of false rationality, including social and academic convention, on the free functioning of the instinctual urges of the human mind.

Surrealist philosophy connects with the theories of psychiatrist Sigmund Freud. Freud asserted that unconscious thoughts (the thoughts one is not aware of) motivate human behavior, and he advocated free association (uncensored expression) and dream analysis to reveal unconscious thoughts.

It is through free association and dream interpretation, that Surrealists believe the wellspring of imagination and creativity can be accessed.

Surrealism also embraces idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness or darkness of the mind. Salvador Dalí, who was quite idiosycratic, explained it as, "The only difference between myself and a madman is I am not MAD!"

Surrealists promote looking to primitive art as an example of expression that is not self-censored.

The radical aim of Surrealism is to revolutionize human experience, including its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects, by freeing people from what is seen as false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. As Breton proclaimed, the true aim of Surrealism is "long live the social revolution, and it alone!"

To this goal, at at various times Surrealists have aligned with communism and anarchism.

Not all Surrealists subscribe to all facets of the philosophy. Historically many were not interested in politcal matters, and this lack of interest manifested rifts in the Surrealism movement.

By the turn of the 21st century, Surrealist philosophy varied amongst Surrealist groups around the globe.

History of Surrealism

Breton's Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 and the publication of the magazine La Révolution surréaliste (The Surrealist Revolution) marked the beginning of the Surrealism as a public agitation.

Five years earlier, Breton and Philippe Soupault wrote the first "automatic book" (spontaneously written), Les Champs Magnétiques.

By December of 1924, the publication La Révolution surréaliste edited by Pierre Naville and Benjamin Perét and later by Breton, was started. Also, a Bureau of Surrealist Research began in Paris and was at one time, under the direction of Antonin Artaud.

In 1926, Louis Aragon wrote Le Paysan de Paris, following the appearance of many Surrealist books, poems, pamphlets, automatic texts and theoretical works published by the Surrealists, including those by René Crevel.

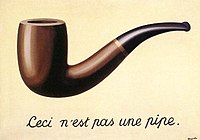

Many of the popular artists in Paris throughout the 1920s and 1930s were Surrealists, including René Magritte, Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Méret Oppenheim, Man Ray, Toyen and Yves Tanguy. Though Breton adored Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, and courted them to join the movement, they did not join.

The Surrealists developed techniques such as automatic drawing (developed by André Masson), automatic painting, decalcomania, frottage, fumage, grattage and parsemage that became significant parts of Surrealist practice. (Automatism was later adapted to the computer.)

Games such as the exquisite corpse also assumed a great importance in Surrealism.

Although sometimes considered exclusively French, Surrealism was international from the beginning, with both the Belgian and Czech groups developing early; the Czech group continues uninterrupted to this day. Some of what have been described as the most significant Surrealist theorists such as Karel Teige from Czechoslovakia, Shuzo Takiguchi from Japan, Octavio Paz from Mexico, also Aime Cesaire and Rene Menil from Martinique, who both started the Surrealist journal Tropiques in 1940, have hailed from other countries. The most radical of Surrealist methods have also hailed from countries other than France, for example, the technique of cubomania was invented by Romanian Surrealist Gherasim Luca.

Interwar Surrealism: Centrality of Breton

Breton, as the leader of the Surrealist movement, not only published its most thorough explanations of its techniques, aims and ideas, but was the individual who drew in, and expelled, writers, artists and thinkers. Through the interwar period he formed the focus of Surrealist activity in Paris, and his writings were enormously influential in spreading Surrealism as a body of thought, in such works Nadja (1928), the Second Surrealist Manifesto (1930), Communicating Vessels (1932), and Mad Love (1937).

To further the revolutionary aim of Surrealism, in 1927 Breton and others joined the Communist Party. (Breton was ousted in 1933.)

The late 1920s were turbulent for the group as several individuals closely associated with Breton left, and several prominent artists entered.

Surrealism continued to expand in public visibility, in Breton's own estimation the high water mark was the 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition.

In 1937, Breton and Leon Trotsky co-authored a Manifesto for an independent revolutionary art[1] on the need for a permanent revolution, and attacked Stalinism and Socialist realism, as the "negation of freedom".

Surrealism also attracted writers from the United Kingdom to Paris including David Gascoyne, who became friends with Paul Éluard and Max Ernst, and translated Breton and Dalí into English. In 1935 he authored A Short Study of Surrealism, and then returned to England during the World War II, where he roomed with Lucian Freud, and continued to write in the Surrealist style for the remainder of his life.

Acéphale was one splinter group that formed (mid-1930s). The group was comprised of some of those disaffected by Breton's increasing rigidity, and structured as a "secret society". Led by Bataille, they published Da Costa Encyclopedia meant to coincide with the 1947 Surrealist exhibition in Paris.

Surrealism during World War II

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the events of 1939 through 1945 in Europe, for a time, overshadowed almost all else. However, after the war, Breton continued to write and espouse the importance of liberating of the human mind. For example in The Tower of Light in (1952).

In 1941, Breton went to the United States, where he founded the short lived magazine VVV, which boasted high production values and a great deal of content, however, its content was increasingly in French, not English. It was American poet Charles Henri Ford and his magazine View which offered Breton a channel for promoting Surrealism in the United States. Ford and Breton had an on again, off again relationship, Breton felt that Ford should work more specifically for Surrealism, and Ford, for his part, resented what he felt to be Breton's attempts to make him "toe the line". Nevertheless, View published an interview between Breton and Nicolas Calas, as well as special issues on Tanguy and Ernst, and in 1945, on Marcel Duchamp.

The special issue on Duchamp was crucial for the public understanding of Surrealism in America, it stressed his connections to Surrealist methods, offered interpretations of his work by Breton, as well as Breton's view that Duchamp represented the bridge between early modern movements such as Futurism and Cubism with Surrealism.

Breton's return to France after the Second World War, began a new phase of surrealist activity in Paris, one which attracted considerable attention; Breton's idea of the phoenix came to symbolize the new effort, and for a time it appeared that Surrealism's ability to combine older perspectives and techniques with new insights (for example, the deemphasis on Marxism) might bolster the argument for its continued importance in the context of 20th century philosophy, art and literature.

Breton's critiques of rationalism and dualism, found a new audience after the Second World War, as his argument that returning to old patterns of behavior would ensure a repeated cycle of conflict seemed increasingly prophetic to French intellectuals while the Cold War mounted. Breton's insistence that Surrealism was not an aesthetic movement, nor a series of techniques and tools, but instead the means to an ongoing revolt against the reduction of humanity to market relationships, religious gestures and misery, meant that his ideas and stances were taken up by many, even those who had never heard of Breton, or read any of his work. The importance of living Surrealism was repeated by Breton and by those writing about him.

The "end" of Surrealism

There is no clear consensus about the end of the Surrealist movement: some historians suggest that the movement was effectively disbanded by WWII, others treat the movement as extending through the 1950s; art historian Sarane Alexandrian (1970) states that "the death of André Breton in 1966 marked the end of Surrealism as an organized movement." However, some who knew Breton, and were part of groups he founded or approved continued to be active until well after his death. For example, Czech Surrealism Group in Prague, though driven underground in 1968, re-emerged in the 1990s. Still other groups and artists, not directly connected to Breton, have claimed the Surrealist label. In addition, Surrealism, as a prominent critique of rationalism and capitalism, and a theory of integrated aesthetics and ethics had influence on later movements, including many aspects of postmodernism.

People involved in Breton's Surrealist group

- Louis Aragon

- Jean Arp

- Georges Bataille

- André Breton

- Giorgio de Chirico

- René Crevel

- Salvador Dalí

- René Daumal

- Robert Desnos

- Paul Éluard

- Max Ernst

- David Gascoyne

- Alberto Giacometti

- Valentine Hugo

- Michel Leiris

- René Magritte

- Roberto Matta

- Joan Miró

- André Masson

- Pierre Naville

- Méret Oppenheim

- Benjamin Perét

- Jacques Prevert

- Man Ray

- Philippe Soupault

- Tristan Tzara

- Yves Tanguy

- Toyen

- Remedios Varo

- Nancy Cunard

- Andre Thirion

Surrealism in the arts

In general usage, the term Surrealism is more often considered a movement in visual arts than the original cultural and philosophical movement. As with many terms, the relationship between the two usages is a matter of some debate outside the movement. (Other examples are romanticism and minimalism, which apply to different ideas and periods in differing contexts.)

Surrealism in visual arts

The relationship between the movement in visual arts and Surrealism as a political and philosophical movement is complex. Many Surrealist artists regarded their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, and Breton was explicit in his belief that Surrealism was first and foremost a revolutionary movement.

Early visual arts Surrealism

Since so many of the artists involved in Surrealism came from the Dada movement, the demarcation between Surrealist and Dadaist art, as with the demarcation between Surrealism and Dada in general, is a drawn differently by different scholars.

The roots of Surrealism in the visual arts run to both Dada and Cubism, as well as the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky and Expressionism, as well as Post-Impressionism. However, it was not the particulars of technique which marked the Surrealist movement in the visual arts, but an the creation of objects from the imagination, from automatism, or from a number of Surrealist techniques.

Masson's automatic drawings of 1923, are often used as a convenient point of difference, since these reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind.

Another example is Alberto Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from pre-classical sculpture. However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen with Le Baiser from 1927 by Max Ernst. The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, where as the second presents an erotic act openly and directly. In the second the influence of Miró and Picasso's drawing style is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, where as the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Giorgio de Chirico was one of the important joining figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted a very primary colour palette, and unornamented epictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. La tour rouge from 1913 shows the stark colour contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 La Nostalgie du poete has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief which defies conventional realistic explanation. He was also a writer. His novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes, with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax and grammar, designed to create a particular atmosphere and frame around its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballet Russe, would create a decorative form of visual Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two that would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Dalí and Magritte.

In 1924, Miro and Masson applied Surrealism theory to painting explicitly leading to the La Peinture Surrealiste Exposition at Gallerie Pierre in 1925, which included work by Man Ray, Masson, Klee and Miró among others. It confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), techniques from Dada, such as photomontage were used.

Galerie Surréaliste opened on March 26, 1926 with an exhibition by Man Ray.

Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s.

1930s

Dalí and Magritte created the most widely recognized images of the movement. Dalí joined the group in 1929, and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935.

Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth by stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, in order to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer.

1931 marked a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: Magritte's La Voix des airs is an example of this process, where three large spheres representing bells hanging above a landscape. Another Surrealist landscape from this same year is Tanguy's Palais promontoire, with its molten forms and liquid shapes. Liquid shapes became the trademark of Dalí, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of clocks that sag as if they are made out of cloth.

The characteristics of this style: a combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychological, came to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modern period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with ones individuality".

Long after personal, political and professional tensions broke up the Surrealist group, Magritte and Dalí continued to define a visual program in the arts. This program reached beyond painting, to encompass photography as well, as can be seen from this Man Ray self portrait whose use of assemblage influenced Robert Rauschenberg's collage boxes.

During the 1930s Peggy Guggenheim, an important art collector married Max Ernst and began promoting work by other Surrealists such as Yves Tanguy and the British artist John Tunnard. However, by the outbreak of the Second World War, the taste of the avant-garde swung decisively towards Abstract Expressionism with the support of key taste makers, including Guggenheim.

World War II and beyond

As with many artistic movements in Europe, the coming of the Second World War proved disruptive: both because of the rift between Breton and Dalí over Dalí's support for Francisco Franco, and because of a diaspora of the members of the Surrealist movement itself. Dalí said to remain a Surrealist forever was like "painting only eyes and noses", and declared he had embarked on a "classic" period; Max Ernst in 1962 said "I feel more affinity for some German Romantics". Magritte began painting what he called his "solar" or "Renoir" style.

The works continued. Many Surrealist artists continued to explore their vocabularies, including Magritte. Many members of the Surrealist movement continued to correspond and meet. (In 1960, Magritte, Duchamp, Ernst, and Man Ray met in Paris.) While Dalí may have been excommunicated by Breton, he neither abandoned the themes from the 1930s, including references to the "persistence of time" in a later painting, nor did he become a depictive "pompier". His classic period did not represent so sharp a break with the past as some descriptions of his work might portray.

During the 1940s Surrealism's influence was also felt in England and America. Mark Rothko took an interest in bimorphic figures, and in England Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Paul Nash used or experimented with Surrealist techniques. However, Conroy Maddox, one of the first British Surrealists, beginning in 1935, remained within the movement, organizing an exhibition of current Surrealist work in 1978, in response to an exhibition which infuriated him because it did not properly represent Surrealism. The exhibition, titled Surrealism Unlimited was in Paris, and attracted international attention. He held his his last one man show in 2002, just before his death in 2005.

Magritte's work became more realistic in its depiction of actual objects, while maintaining the element of juxtaposition, such as in 1951's Personal Values and 1954's Empire of Light. Magritte continued to produce works which have entered artistic vocabulary, such as Castle in the Pyrenees which refers back to Voix from 1931, in its suspension over a landscape.

Other figures from the Surrealist movement were expelled, Roberto Matta for example, but by their own description "remained close to Surrealism."

Many new artists explicitly took up the Surrealist banner for themselves, some following what they saw as the path of Dalí, others holding to views they derived from Breton. Duchamp continued to produce sculpture and, at his death, was working on an installation with the realistic depiction of a woman viewable only through a peephole. Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois continued to work, for example with Tanning's Rainy Day Canape from 1970.

The 1960s saw an expansion of Surrealism with the founding of The West Coast Surrealist Group as recognized by Breton's personal assistant Jose Pierre and also Surrealist Movement in the United States.

That Surrealism has remained commercially successful and popularly recognized has lead many people associated with the Breton's Surrealist group to criticise more general uses of the term. They argue that many self-identified Surrealists are not grounded in Breton's work and the techniques of the movement.

Surrealistic art remains enormously popular with museum patrons. In 2001 Tate Modern held an exhibition of Surrealist art that attracted over 170,000 visitors in its run. Having been one of the most important of movements in the Modern period, Surrealism proceeded to inspire a new generation seeking to expand the vocabulary of art.

Surrealism in literature

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Surrealism in music

- Main article: Surrealism (music).

In the 1920s several composers were influenced by Surrealism, or by individuals in the Surrealist movement. Among these were Bohuslav Martin, Andre Souris, and Edgar Varese, who stated that his work Arcana was drawn from a dream sequence. Souris in particular was associated with the movement: he had a long, if sometimes spotty, relationship with Magritte, and worked on Paul Nouge's publication Adieu Marie.

French composer Pierre Boulez wrote a piece called explosante-fixe (1972), inspired by Breton's mad love.

Even though Breton by 1946 responded rather negatively to the subject of music with his essay Silence is Golden, later Surrealists have been interested in, and found parallels to Surrealism in, the improvisation of jazz (as alluded to above), and the blues (Surrealists such as Paul Garon have written articles and full-length books on the subject). Jazz and blues musicians have occasionally reciprocated this interest; for example, the 1976 World Surrealist Exhibition included such performances by Honeyboy Edwards.

Readers of the Surrealists have also analysed reggae and, later, rap, and some rock bands such as The Psychedelic Furs. In addition to musicians who have been influenced by Surrealism (including some influence in rock — the title of the 1967 psychedelic Jefferson Airplane album Surrealistic Pillow was obviously inspired by the movement), such as the experimental group Nurse With Wound (whose album title Chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and umbrella is taken from a line in Lautreamont's Maldoror), Surrealist music has included such explorations as those of Hal Rammel.

Surrealism in film

Surrealist films include Un chien andalou and L'Âge d'Or by Luis Buñuel and Dalí.

Surrealist and film theorist Robert Benayoun has written books on Tex Avery, Woody Allen, Buster Keaton and the Marx Brothers.

Some have described David Lynch as a Surrealist filmmaker. He has never participated in the Surrealist movement or in any Surrealist activity, but there are arguably some aspects of many of his films that are of Surrealist interest.

Surrealism in television

Some have found the television series The Prisoner to be of Surrealist interest.

Impact of Surrealism

While Surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has been said to transcend them; Surrealism has had an impact in many other fields. In this sense, Surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "Surrealists", or those sanctioned by Breton, rather, it refers to a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate imagination.

In addition to Surrealist ideas that are grounded in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, Surrealism is seen by its advocates as being inherently dynamic and is dialectic in its thought. Surrealists have also drawn on sources as seemingly diverse as Clark Ashton Smith, Montague Summers, Fantomas, Bugs Bunny, comic strips, the obscure poet Samuel Greenberg and the hobo writer and humourist T-Bone Slim. One might say that Surrealist strands may be found in movements such as Free Jazz (Don Cherry, Sun Ra, etc.) and even in the daily lives of people in confrontation with limiting social conditions. Thought of as the effort of humanity to liberate imagination as an act of insurrection against society, Surrealism dates back to, or finds precedents in, the alchemists, possibly Dante, various heretical groups, Hieronymus Bosch, Marquis de Sade, Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautreamont and Arthur Rimbaud. Surrealists believe that non-Western cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for Surrealist activity because some may strike up a better balance between instrumental reason and the imagination in flight than Western culture.

Some artists, such as H.R. Giger in Europe, who won an Academy Award for his stage set, and who also designed the "creature," in the movie Alien, have been popularly called "Surrealists," though Giger is a visionary artist and it is speculated the he doesn't claim to be Surrealist.

The Society for the Art of Imagination has come in for particularly bitter criticism from a self-characterised Surrealist movement (although this criticism has been characterized by at least one anonymous individual as coming from "the Marxists [sic] Surrealist groups, who maintain small contingents worldwide;" he has also pointed out what he considers the hypocrisy of any Surrealist criticism of the Society for the Art of Imagination given that Kathleen Fox designed the cover of issue 4 of the bulletin of the Groupe de Paris du Mouvement Surrealiste and also participated in the 2003 Brave Destiny[2] show at the Williamsburg Art & Historical Center. Though some presented Brave Destiny as the largest-ever exhibit of Surrealist artists, the show was officially billed as exhibiting "Surrealism, Surreal/Conceptual, Visionary, Fantastic, Symbolism, Magic Realism, the Vienna School, Neuve Invention, Outsider, Naïve, the Macabre, Grotesque and Singulier Art.)"

See also

Techniques, games and humor

Related art movements and genres

Sources

- André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism containing the 1st, 2nd and introduction to a possible 3rd Manifesto, and in addition the novel The Soluble Fish and political aspects of the Surrealist movement. ISBN 0472179004.

- What is Surrealism?: Selected Writings of André Breton. ISBN 0873488229.

- André Breton, Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism (Gallimard 1952) (Paragon House English rev. ed. 1993). ISBN 1569249709.

- André Breton. The Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism, reprinted in:

- Marguerite Bonnet, ed. (1988). Oeuvres complètes, 1:328. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

Other sources

- Guillaume Appollinaire (1917, 1991). Program note for Parade, printed in Oeuvres en prose complètes, 2:865-866, Pierre Caizergues and Michel Décaudin, eds. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- Gerard Durozoi, History of the Surrealist Movement (translated by Alison Anderson, University of Chicago Press). 2004. ISBN 0226174115.

- Rosemont, Franklin, Surrealism and Its Popular Accomplices San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books (1980). ISBN 087286121X.

- Brotchie, Alastair and Gooding, Mel, eds. A Book of Surrealist Games Berkeley, CA: Shambhala (1995). ISBN 1570620849.

- Moebius, Stephan. Die Zauberlehrlinge. Soziologiegeschichte des Collège de Sociologie. Konstanz: UVK 2006. (About the College of Sociology, its members and sociological impacts).

- Alexandrian, Sarane. Surrealist Art London: Thames & Hudson, 1970.

- Melly, George Paris and the Surrealists Thames & Hudson. 1991.

- Lewis, Helena The Politics Of Surrealism 1988

- Caws, Mary Ann Surrealist Painters and Poets: An Anthology 2001 MIT Press