Democritus

Democritus | |

|---|---|

| Born | ca. 460 BC |

| Died | ca. 370 BC |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western (ancient) Philosophy |

| School | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

Main interests | metaphysics / mathematics / astronomy |

Notable ideas | distant star theory |

Democritus ([Δημόκριτος, Dēmokritos] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), "chosen of the people") (ca. 460 BCE – ca. 370 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece.[1] He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos.[2]

His exact contributions are difficult to disentangle from his mentor Leucippus, as they are often mentioned together in texts. Their hypothesis on atoms, taken from Leucippus, is remarkably similar to modern science's understanding of atomic structure, and avoided many of the errors of their contemporaries. Largely ignored in Athens, Democritus was nevertheless well-known to his fellow northern-born philosopher Aristotle. Plato is said to have disliked him so much that he wished all his books burnt.[1] Many consider Democritus to be the "father of modern science".[3]

Life

Democritus was born in the city of Abdera in Thrace, an Ionian colony of Teos,[4] although some called him a Milesian.[5] His year of birth was 460 BC according to Apollodorus, who is probably more reliable than Thrasyllus who placed it ten years earlier.[6] John Burnet has argued that the date of 460 is "too early", since according to Diogenes Laërtius ix.41, Democritus said that he was a "young man (neos)" during Anaxagoras' old age (circa 440–428).[7] It was said that Democritus' father was so wealthy that he received Xerxes on his march through Abdera. Democritus spent the inheritance which his father left him on travels into distant countries, to satisfy his thirst for knowledge. He travelled to Asia, and was even said to have reached India and Ethiopia.[8] We know that he wrote on Babylon and Meroe; he must also have visited Egypt, and Diodorus Siculus states that he lived there for five years.[9] He himself declared[10] that among his contemporaries none had made greater journeys, seen more countries, and met more scholars than himself. He particularly mentions the Egyptian mathematicians, whose knowledge he praises. Theophrastus, too, spoke of him as a man who had seen many countries.[11] During his travels, according to Diogenes Laërtius, he became acquainted with the Chaldean magi. A certain "Ostanes", one of the magi accompanying Xerxes was also said to have taught him.[12]

After returning to his native land he occupied himself with natural philosophy. He traveled throughout Greece to acquire a knowledge of its culture. He mentions many Greek philosophers in his writings, and his wealth enabled him to purchase their writings. Leucippus, the founder of the atomism, was the greatest influence upon him. He also praises Anaxagoras.[13] Diogenes Laertius says that he was friends with Hippocrates.[14] He may have been acquainted with Socrates, but Plato does not mention him and Democritus himself is quoted as saying, "I came to Athens and no one knew me."[15]. Though Aristotle viewed him as a pre-Socratic[16], it should be noticed that since Socrates was born ca. 469 BC (about 9 years before Democritus), it is very possible that Aristotle's remark was not meant to be a chronological one, but directed towards his philosophical similarity with other pre-Socratic thinkers.

The many anecdotes about Democritus, especially in Diogenes Laërtius, attest to his disinterestedness, modesty, and simplicity, and show that he lived exclusively for his studies. One story has him deliberately blinding himself in order to be less disturbed in his pursuits;[17] it may well be true that he lost his sight in old age. He was cheerful, and was always ready to see the comical side of life, which later writers took to mean that he always laughed at the foolishness of people.[18]

He was highly esteemed by his fellow-citizens, "because," as Diogenes Laërtius says, "he had foretold them some things which events proved to be true," which may refer to his knowledge of natural phenomena. According to Diodorus Siculus,[19] Democritus died at the age of 90, which would put his death around 370 BC, but other writers have him living to 104,[20] or even 109.[21]

Popularly known as the Laughing Philosopher, the terms Abderitan laughter, which means scoffing, incessant laughter, and Abderite, which means a scoffer, are derived from Democritus.[22]

Philosophy and science

Democritus followed in the tradition of Leucippus, who seems to have come from Miletus, and he carried on the scientific rationalist philosophy associated with that city. They were both strict determinists and thorough materialists, believing everything to be the result of natural laws, and they will have nothing to do with chance or randomness. Unlike Aristotle or Plato, the atomists attempted to explain the world without the presuppositions of purpose, prime mover, or final cause. For the atomists questions should be answered with a mechanistic explanation ("What earlier circumstances caused this event?"), while their opponents searched for teleological explanations ("What purpose did this event serve?"). The history of modern science has shown that mechanistic questions lead to scientific knowledge, especially in physics, while the teleological question can be useful in biology, in adaptationist reasoning at providing proximate explanations, though the deeper evolutionary explanations are thoroughly mechanistic. The atomists looked for mechanistic questions, and gave mechanistic answers. Their successors until the Renaissance became occupied with the teleological question, which ultimately hindered progress.[23]

Atomic hypothesis

The theory of Leucippus, got by Democritus, holds everything to be composed of atoms, which are physically, but not geometrically, indivisible; that between atoms lies empty space; that atoms are indestructible; have always been, and always will be, in motion; that there are an infinite number of atoms, and kinds of atoms, which differ in shape, and size. Of the weight of atoms, Democritus said "The more any indivisible exceeds, the heavier it is." But their exact position on weight of atoms is disputed.[1]

Leucippus is widely credited with being the first to develop the theory of atomism. Nevertheless, this notion has been called into question by some scholars. Newton, for instance, credits the obscure Moschus the Phoenician (whom he believed to be the biblical Moses) as the inventor of the idea.[24] The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, "This theologically motivated view does not seem to claim much historical evidence, however."[25]

Aristotle criticized the atomists for not providing an account for the cause of the original motion of atoms, but in this they have been vindicated as more scientific than their critics. Even if a prime mover or creator is supposed, that force remains unaccounted for. The theory of the atomists is, in fact, more nearly that of modern science than any other theory of antiquity. However, their theories were not wholly empirical, and their belief was devoid of any solid foundation. The atomists can be viewed as having hit on a hypothesis for which, two thousand years later, some evidence happened to be found.[26]

Void hypothesis

The atomistic void hypothesis was a response to the paradoxes of Parmenides and Zeno, the founders of metaphysical logic, who put forth difficult to answer arguments in favor of the idea that there can be no movement. They held that any movement would require a void—which is nothing—but a nothing cannot exist. The Parmenidean position was "You say there is a void; therefore the void is not nothing; therefore there is not the void." The position of Parmenides appeared validated by the observation that where there seems to be nothing there is air, and indeed even where there is not matter there is something, for instance light waves.

The atomists agreed that motion required a void, but simply ignored the argument of Parmenides on the grounds that motion was an observable fact. Therefore, they asserted, there must be a void. This idea survived in a refined version as Newton's theory of absolute space, which met the logical requirements of attributing reality to not-being. Einstein's theory of relativity provided a new answer to Parmenides and Zeno, with the insight that space by itself is relative and cannot be separated from time as part of a generally curved space-time manifold. Consequently, Newton's refinement is now considered superfluous.[27]

Epistemology

The knowledge of truth according to Democritus is difficult, since the perception through the senses is subjective. As from the same senses derive different impressions for each individual, then through the sense-impressions we cannot judge the truth. We can only interpret the sense data through the intellect and grasp the truth, because the truth (aletheia) is at the bottom (en bythoe).

- “And again, many of the other animals receive impressions contrary to ours; and even to the senses of each individual, things do not always seem the same. Which then, of these impressions are true and which are false is not obvious; for the one set is no more true than the other, but both are alike. And this is why Democritus, at any rate, says that either there is no truth or to us at least it is not evident.”[28]

- “Democritus says: By convention hot, by convention cold, but in reality atoms and void, and also in reality we know nothing, since the truth is at bottom.”[29]

There are two kinds of knowing, the one he calls “legitimate” (gnesie: genuine) and the other “bastard” (skotie: obscure). The “bastard” knowledge is concerned with the perception through the senses, therefore it is insufficient and subjective. The reason is that the sense-perception is due to the effluences of the atoms (aporroai) from the objects to the senses. When these different shapes of atoms come to us, they stimulate our senses according to their shape, and our sense-impressions arise from those stimulations.[30]

The second sort of knowledge, the “legitimate” one, can be achieved through the intellect, in other words, all the sense-data from the “bastard” must be elaborated through reasoning. In this way one can get away from the false perception of the “bastard” knowledge and grasp the truth through the inductive reasoning. After taking into account the sense-impressions, one can examine the causes of the appearances, draw conclusions about the laws that govern the appearances, and discover the causality (aetiologia) by which they are related. This is the procedure of thought from the parts to the whole or else from the apparent to non-apparent (inductive reasoning). This is one example of why Democritus is considered to be an early scientific thinker. The process is reminiscent of that by which science gathers its conclusions.

- “But in the Canons Democritus says there are two kinds of knowing, one through the senses and the other through the intellect. Of these he calls the one through the intellect ‘legitimate’ attesting its trustworthiness for the judgement of truth, and through the senses he names ‘bastard’ denying its inerrancy in the discrimination of what is true. To quote his actual words: Of knowledge there are two forms, one legitimate, one bastard. To the bastard belong all this group: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch. The other is legitimate and separate from that. Then, preferring the legitimate to the bastard, he continues: When the bastard can no longer see any smaller, or hear, or smell, or taste, or perceive by touch, but finer matters have to be examined, then comes the legitimate, since it has a finer organ of perception.”[31]

- “In the Confirmations ... he says: But we in actuality grasp nothing for certain, but what shifts in accordance with the condition of the body and of the things (atoms) which enter it and press upon it.”[32]

- “Democritus used to say that 'he prefers to discover a causality rather than become a king of Persia'.”[33]

Ethics and politics

The ethics and politics of Democritus come to us mostly in the form of maxims. He says that "Equality is everywhere noble," but he is not encompassing enough to include women or slaves in this sentiment. Poverty in a democracy is better than prosperity under tyrants, for the same reason one is to prefer liberty over slavery. Those in power should "take it upon themselves to lend to the poor and to aid them and to favor them, then is there pity and no isolation but companionship and mutual defense and concord among the citizens and other good things too many to catalogue." Money when used with sense leads to generosity and charity, while money used in folly leads to a common expense for the whole society— excessive hoarding of money for one's children is avarice. While making money is not useless, he says, doing so as a result of wrong-doing is the "worst of all things." He is on the whole ambivalent towards wealth, and values it much less than self-sufficiency. He disliked violence but was not a pacifist: he urged cities to be prepared for war, and believed that a society had the right to execute a criminal or enemy so long as this did not violate some law, treaty, or oath.[2][27]

Goodness, he believed, came more from practice and discipline than from innate human nature. He believed that one should distance oneself from the wicked, stating that such association increases disposition to vice. Anger, while difficult to control, must be mastered in order for one to be rational. Those who take pleasure from the disasters of their neighbors fail to understand that their fortunes are tied to the society in which they live, and they rob themselves of any joy of their own. He advocated a life of contentment with as little grief as possible, which he said could not be achieved through either idleness or preoccupation with worldly pleasures. Contentment would be gained, he said, through moderation and a measured life; to be content one must set their judgment on the possible and be satisfied with what one has—giving little thought to envy or admiration. Democritus approved of extravagance on occasion, as he held that feasts and celebrations were necessary for joy and relaxation. He considers education to be the noblest of pursuits, but cautioned that learning without sense leads to error.[2][27]

Mathematics

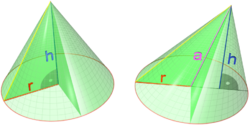

Democritus was also a pioneer of mathematics and geometry in particular. We only know this through citations of his works (titled On Numbers, On Geometrics, On Tangencies, On Mapping, and On Irrationals) in other writings, since most of Democritus' body of work did not survive the Middle Ages. Democritus was among the first to observe that a cone or pyramid has one-third the volume of a cylinder or prism respectively with the same base and height. Also, a cone divided in a plane parallel to its base produces two surfaces. He pointed out that if the two surfaces are commensurate with each other, then the shape of the body would appear to be a cylinder, as it is composed of equal rather than unequal circles. However, if the surfaces are not commensurate, then the side of a cone is not smooth but jagged like a series of steps.[34]

Anthropology, biology, and cosmology

His work on nature is known through citations of his books on the subjects, On the Nature of Man, On Flesh (two books), On Mind, On the Senses, On Flavors, On Colors, Causes concerned with Seeds and Plants and Fruits, and Causes concerned with Animals (three books).[2] He spent much of his life experimenting with and examining plants and minerals, and wrote at length on many scientific topics.[35] Democritus thought that the first humans lived an anarchic and animal sort of life, going out to forage individually and living off the most palatable herbs and the fruit which grew wild on the trees. They were driven together into societies for fear of wild animals, he said. He believed that these early people had no language, but that they gradually began to articulate their expressions, establishing symbols for every sort of object, and in this manner came to understand each other. He says that the earliest men lived laboriously, having none of the utilities of life; clothing, houses, fire, domestication, and farming were unknown to them. Democritus presents the early period of mankind as one of learning by trial and error, and says that each step slowly lead to more discoveries; they took refuge in the caves in winter, stored fruits that could be preserved, and through reason and keenness of mind came to build upon each new idea.[2][36]

Democritus held that the earth was round, and stated that originally the universe was comprised of nothing but tiny atoms churning in chaos, until they collided together to form larger units—including the earth and everything on it.[2] He surmised that there are many worlds, some growing, some decaying; some with no sun or moon, some with several. He held that every world has a beginning and an end, and that a world could be destroyed by collision with another world. His cosmology can be summarized with assistance from Shelley: Worlds rolling over worlds; From creation to decay; Like the bubbles on a river; Sparkling, bursting, borne away.[37]

Works

- Ethics

- Pythagoras

- On the Disposition of the Wise Man

- On the Things in Hades

- Tritogenia

- On Manliness or On Virtue

- The Horn of Amaltheia

- On Contentment

- Ethical Commentaries

- Natural science

- The Great World-ordering (may have been written by Leucippus)

- Cosmography

- On the Planets

- On Nature

- On the Nature of Man or On Flesh (two books)

- On the Mind

- On the Senses

- On Flavors

- On Colors

- On Different Shapes

- On Changing Shape

- Buttresses

- On Images

- On Logic (three books)

- Nature

- Heavenly Causes

- Atmospheric Causes

- Terrestrial Causes

- Causes Concerned with Fire and Things in Fire

- Causes Concerned with Sounds

- Caused Concerned with Seeds and Plants and Fruits

- Causes Concerned with Animals (three books)

- Miscellaneous Causes

- On Magnets

- Mathematics

- On Different Angles or O contact of Circles and Spheres

- On Geometry

- Geometry

- Numbers

- On Irrational Lines and Solids (two books)

- Planispheres

- On the Great Year or Astronomy (a calendar)

- Contest of the Waterclock

- Description of the Heavens

- Geography

- Description of the Poles

- Description of Rays of Light

- Literature

- On the Rhythms and Harmony

- On Poetry

- On the Beauty of Verses

- On Euphonious and Harsh-sounding Letters

- On Homer

- On Song

- On Verbs

- Names

- Technical works

- Prognosis

- On Diet

- Medical Judgment

- Causes Concerning Appropriate and Inappropriate Occasions

- On Farming

- On Painting

- Tactics

- Fighting in Armor

- Commentaries

- On the Sacred Writings of Babylon

- On Those in Meroe

- Circumnavigation of the Ocean

- On History

- Chaldaean Account

- Phrygian Account

- On Fever and Coughing Sicknesses

- Legal Causes

- Problems[38]

Institutes named after Democritus

After Democritus are named the following institutions:

Numismatics

Democritus was depicted on the following contemporary coins/banknotes:

- the reverse of the Greek 10 drachmas coin of 1976–2001.[39]

- the obverse of the Greek 100 drachmas banknote of 1967–1978.[40]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Russell, pp.64–65.

- ^ a b c d e f Barnes (1987).

- ^ Pamela Gossin, Encyclopedia of Literature and Science, 2002.

- ^ Aristotle, de Coel. iii.4, Meteor. ii.7

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, ix.34, etc.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, ix.41.

- ^ John Burnet (1955). Greek Philosophy: Thales to Plato, London: Macmillan, p.194.

- ^ Cicero, de Finibus, v.19; Strabo, xvi.

- ^ Diodorus, i.98.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, i.

- ^ Aelian, Varia Historia, iv. 20; Diogenes Laërtius, ix. 35.

- ^ Tatian, Orat. cont. Graec. 17. "However, this Democritus, whom Tatian identified with the philosopher, was a certain Bolos of Mendes who, under the name of Democritus, wrote a book on sympathies and antipathies" – Owsei Temkin (1991), Hippocrates in a World of Pagans and Christians, p.120. JHU Press.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, ii.14; Sextus vii.140.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, ix.42.

- ^ Diogenes Laertius 9.36 and Cicero Tusculanae Quaestiones 5.36.104, cited in p. 349 n. 2 of W. K. C. Guthrie (1965), A History of Greek Philosophy, vol. 2, Cambridge.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaph. xiii.4; Phys. ii.2, de Partib. Anim. i.1

- ^ Cicero, de Finibus v.29; Aulus Gellius, x.17; Diogenes Laërtius, ix.36; Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones v.39.

- ^ Seneca, de Ira, ii.10; Aelian, Varia Historia, iv.20.

- ^ Diodorus, xiv.11.5.

- ^ Lucian, Macrobii 18

- ^ Hipparchus ap. Diogenes Laërtius, ix.43.

- ^ Brewer, E. Cobham (1978 [reprint of 1894 version]). The Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. Edwinstowe, England: Avenel Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-517-259-21-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Russell.

- ^ Derek Gjertsen (1986), The Newton Handbook, p.468.

- ^ Sylvia Berryman (2005). "Ancient Atomism", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. – Retrieved on 15 July 2009.

- ^ Russell, p.66.

- ^ a b c Russell, pp.69–71.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics iv.1009 b 7.

- ^ Fr. 117, Diogenes Laërtius ix.72.

- ^ Fr. 135, Theophrastus12, De Sensu 49–83.

- ^ Fr. 11, Sextus vii.138.

- ^ Fr. 9, Sextus vii.136.

- ^ Fr. 118

- ^ Fragment 9, The Pre-Socratics, Philip Wheelwright Ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 1966, p.183.

- ^ Petronius.

- ^ Diodorus I.viii.1–7.

- ^ Russell, pp.71–72.

- ^ Barnes (1987), pp.245–246

- ^ Bank of Greece. Drachma Banknotes & Coins: 10 drachmas. – Retrieved on 27 March 2009.

- ^ J. Bourjaily. Banknotes featuring Scientists and Mathematicians. – Retrieved on 7 December 2009.

References

- BAILEY, (1928). The Greek Atomists and Epicurus. Oxford.

- BAKALIS, (2005). Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics: Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5.

- BARNES, (1982). The Presocratic Philosophers, Routledge Revised Edition.

- _____ (1987). Early Greek Philosophy, Penguin.

- BURNET, (2003). Early Greek Philosophy, Kessinger Publishing

- DIODORUS (1st century BCE). Bibliotheca historica.

- DIOGENES (3rd century CE). Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.

- FREEMAN, (2008). Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Forgotten Books, ISBN 978-1-606-80256-4.

- GUTHRIE, (1979) A History of Greek Philosophy – The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus, Cambridge University Press.

- KIRK, and M. SCHOFIELD (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition.

- MELCHERT, NORMAN (2002). The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - PYLE, (1997). 'Democritus and Heracleitus: An Excursus on the Cover of this Book,' Milan and Lombardy in the Renaissance. Essays in Cultural History. Rome, La Fenice. (Istituto di Filologia Moderna, Università di Parma: Testi e Studi, Nuova Serie: Studi 1.) (Fortuna of the Laughing and Weeping Philosophers topos)

- PETRONIUS (late 1st century CE). Satyricon. Trans. William Arrowsmith. New York: A Meridian Book, 1987.

- RUSSELL, (1972). A History of Western Philosophy, Simon & Schuster.

- SEXTUS (ca. 200 CE). Adversus Mathematicos.

External links

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Democritus", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Democritus in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Democritus and Leucippus

- Democritus in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy