Gender inequality

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2010) |

Gender inequality refers to disparity between individuals due to gender. It emerges from differences in both socially constructed gender roles as well as biologically through chromosome, brain structure, and hormonal differences.[1] Gender systems are often dichotomous and hierarchical; binary gender systems may reflect the inequalities that manifest in numerous dimensions of daily life. Gender inequality stems from distinctions, whether empirically grounded or socially constructed. (On differences between the sexes, see Sex and psychology.)

Natural gender differences

There are natural differences between the sexes based on biological and anatomic factors, most notably differing reproductive roles. Biological differences include chromosomes, brain structure, and hormonal differences.[1] There is a natural difference also in the relative physical strengths (on average) of the sexes.

In the workplace

Income disparities linked to job stratification

This article appears to contradict the article Gender pay gap. |

Wage discrimination is the discrepancy of wages between two groups due to a bias towards or against a specific trait with all other characteristics of both groups being equivalent. In the case of gender inequality, wage discrimination exists between the male and female gender. Historically, gender inequality has favored men over similarly qualified women.[2]

Income disparity between genders stems from processes that determine the quality of jobs and earnings associated with jobs. Earnings associated with jobs will cause income inequality to take form in the placement of individuals into particular jobs through individual qualifications or stereotypical norms. Placement of men or women into particular job categories can be supported through the human capital theories of qualifications of individuals or abilities associated with biological differences in men and women. Conversely, the placement of men or women into separate job categories is argued to be caused by social status groups who desire to keep their position through the placement of those in lower statuses to lower paying positions.[3]

Human capital theories refer to the education, knowledge, training, experience, or skill of a person which makes them potentially valuable to an employer. This has historically been understood as a cause of the gendered wage gap but is no longer a predominant cause as women and men in certain occupations tend to have similar education levels or other credentials. Even when such characteristics of jobs and workers are controlled for, the presence of women within a certain occupation leads to lower wages. This earnings discrimination is considered to be a part of pollution theory. This theory suggests that jobs which are predominated by women offer lower wages than do jobs simply because of the presence of women within the occupation. As women enter an occupation, this reduces the amount of prestige associated with the job and men subsequently leave these occupations. The entering of women into specific occupations suggests that less competent workers have begun to be hired or that the occupation is becoming deskilled. Men are reluctant to enter female-dominated occupations because of this and similarly resist the entrance of women into male-dominated occupations.[4]

The gendered income disparity can also be attributed in part to occupational segregation, where groups of people are distributed across occupations according to ascribed characteristics; in this case, gender. Occupational gender segregation can be understood to contain two components or dimensions; horizontal segregation and vertical segregation. With horizontal segregation, occupational sex segregation occurs as men and women are thought to possess different physical, emotional, and mental capabilities. These different capabilities make the genders vary in the types of jobs they are suited for. This can be specifically viewed with the gendered division between manual and non-manual labor. With vertical segregation, occupational sex segregation occurs as occupations are stratified according to the power, authority, income, and prestige associated with the occupation and women are excluded from holding such jobs.[4]

As women entered the workforce in larger numbers since the 1960s, occupations have become segregated based on the amount femininity or masculinity presupposed to be associated with each occupation. Census data suggests that while some occupations have become more gender integrated (mail carriers, bartenders, bus drivers, and real estate agents), occupations including teachers, nurses, secretaries, and librarians have become female-dominated while occupations including architects, electrical engineers, and airplane pilots remain predominately male in composition.[5] Based on the census data, women occupy the service sector jobs at higher rates than men. Women’s overrepresentation in service sector jobs as opposed to jobs that require managerial work acts as a reinforcement of women and men into traditional gender roles that causes gender inequality.[6]

Once factors such as experience, education, occupation, and other job-relevant characteristics have been taken into account, 41% of the male-female wage gap remains unexplained. As such, considerations of occupational segregation and human capital theories are together not enough to understand the continued existence of a gendered income disparity.[4]

The glass ceiling effect is also considered a possible contributor to the gender wage gap or income disparity. This effect suggests that gender provides significant disadvantages towards the top of job hierarchies which become worse as a person’s career goes on. The term glass ceiling implies that invisible or artificial barriers exist which prevent women from advancing within their jobs or receiving promotions. These barriers exist in spite of the achievements or qualifications of the women and still exist when other characteristics that are job-relevant such as experience, education, and abilities are controlled for. The inequality effects of the glass ceiling are more prevalent within higher-powered or higher income occupations, with fewer women holding these types of occupations. The glass ceiling effect also indicates the limited chances of women for income raises and promotion or advancement to more prestigious positions or jobs. As women are prevented by these artificial barriers from receiving job promotions or income raises, the effects of the inequality of the glass ceiling increase over the course of a woman’s career.[8]

Statistical discrimination is also cited as a cause for income disparities and gendered inequality in the workplace. Statistical discrimination indicates the likelihood of employers to deny women access to certain occupational tracks because women are more likely than men to leave their job or the labor force when they become married or pregnant. Women are instead given positions that dead-end or jobs that have very little mobility.[2]

In Third World countries such as the Dominican Republic, female entrepreneurs are statistically more prone to failure in business. In the event of a business failure women often return to their domestic lifestyle despite the absence of income. On the other hand, men tend to search for other employment as the household is not a priority.[9]

The gender earnings ratio suggests that there has been an increase in women’s earnings comparative to men. Men’s plateau in earnings began after the 1970s, allowing for the increase in women’s wages to close the ratio between incomes. Despite the smaller ratio between men and women’s wages, disparity still exists. Census data suggests that women’s earnings are 71 percent of men’s earnings in 1999.[5]

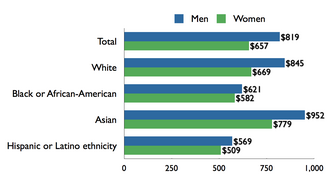

The gendered wage gap varies in its width among different races. Whites comparatively have the greatest wage gap between the genders. With whites, women earn 78% of the wages that white men do. With African Americans, women earn 90% of the wages that African American men do. With people of Hispanic origin, women earn 88% of the wages that men of Hispanic origin do.

There are some exceptions where women earn more than men: According to a survey on gender pay inequality by the International Trade Union Confederation, female workers in the Gulf state of Bahrain earn 40 per cent more than male workers.[10]

Professional education and careers

The gender gap also appeared to narrow considerably beginning in the mid-1960s. Where some 5% of first-year students in professional programs were female in 1965, by 1985 this number had jumped to 40% in law and medicine, and over 30% in dentistry and business school.[11] Before the highly effective birth control pill was available, women planning professional careers, which required a long-term, expensive commitment, had to "pay the penalty of abstinence or cope with considerable uncertainty regarding pregnancy."[12] This control over their reproductive decisions allowed women to more easily make long-term decisions about their education and professional opportunities. Women are highly underrepresented on boards of directors and in senior positions in the private sector.[13]

Additionally, with reliable birth control, young men and women had more reason to delay marriage. This meant that the marriage market available to any one women who "delay[ed] marriage to pursue a career...would not be as depleted. Thus the Pill could have influenced women's careers, college majors, professional degrees, and the age at marriage."[14]

Specifically in China, birth control has become a necessity of the job for women that migrate from rural to urban China. With little job options left, they become sex workers and having some form of birth control helps to ensure their safety. However, the government of China does not regulate prostitution in China, making it more difficult for women to gain access to birth control or to demand that the men use condoms. This doesn't allow for the women to be fully protected, since their health and safety is in jeopardy when they disobey.[15]

Customer preference studies

A 2009 study conducted by David R. Hekman and colleagues found that customers who viewed videos featuring a black male, a white female, or a white male actor playing the role of an employee helping a customer were 19 percent more satisfied with the white male employee's performance, suggesting customer bias as a reason why white men continue to earn 25 percent more than equally-well performing women and minorities.[16] Forty five percent of the customers were women and 41 percent were non-white, indicating to the researchers that even women and minority customers prefer white men. In a second study, they found that white male doctors were rated as more approachable and competent than equally-well performing women or minority doctors. They interpret their findings to suggest that employers are willing to pay more for white male employees because employers are customer driven and customers are happier with white male employees. They also suggest that what is required to solve the problem of wage inequality is to change customer biases, not necessarily to pay women more.[17][18][19][20]

This discrepancy with race can be cited back to 1939, when Dr. Kenneth Clark and his wife performed an experiment with dolls. In order to prove that separate but equal was actually not equal, they asked black children to choose between white dolls and black dolls. The results were that the white males were the nice dolls and the ones that the children wanted to play with. Throughout history we can see that white males are perceived as more approachable and given an advantage in society.[21]

At home

Gender roles in parenting and marriage

Sigmund Freud suggested that biology determines gender identity through identification with either the mother or father. While some people agree with Freud, others argue that the development of the gendered self is not completely determined by biology based around one's relationship to the penis, but rather the interactions that one has with the primary caregiver(s).

According to the non-Freudian view, gender roles develop through internalization and identification during childhood. From birth, parents interact differently with children depending on their sex, and through this interaction parents can instill different values or traits in their children on the basis of what is normative for their sex. This internalization of gender norms can be seen through the example of which types of toys parents typically give to their children (“feminine” toys such as dolls often reinforce interaction, nurturing, and closeness, “masculine” toys such as cars or fake guns often reinforce independence, competitiveness, and aggression).[1] Education also plays an integral role in the creation of gender norms.[22]

Gender roles permeate throughout life and help to structure parenting and marriage, especially in relation to work in and outside the home.

Attempts in equalizing household work

Despite the increase in women in the labor force since the mid-1900s, traditional gender roles are still prevalent in American society. Women are usually expected to put their educational and career goals on hold in order to raise children, while their husbands work. However, there are women who choose to work as well as fulfill their gender role of cleaning the house and taking care of the children. Despite the fact that different households may divide chores more evenly, there is evidence that supports that women have retained the primary caregiver role within familial life despite contributions economically. This evidence suggest that women who work outside the home often put an extra 18 hours a week doing household or childcare related chores as opposed to men who average 12 minutes a day in childcare activities.[23] In addition to a lack of interest in the home on the part of some men, some women may bar men from equal participation in the home which may contribute to this disparity.[24]

Gender inequalities in relation to technology

Although the current generation is overall technology savvy, men typically are more skillful in technology. Surveys show that men rate their technological skills in activities such as basic computer functions and online participatory communication higher than women.[25]

Explanations

Structural marginalization

Gender inequalities often stem from social structures that have institutionalized conceptions of gender differences.

Marginalization occurs on an individual level when someone feels as if they are on the fringes or margins of their respective society. This is a social process and displays how current policies in place can affect people. For example, media advertisements display young girls with easy bake ovens (promoting being a housewife) as well as with dolls that they can feed and change the diaper of (promoting being a mother). When women are not the stereotypical housewife and mother, they have to face the consequences that come along with that.

The Politics of NGOs

Non-governmental organizations (NGO's) have the ability to create change. Certain NGO's, such as the Kiva (organization) promote women entrepreneurs. Currently, Kiva distributes loans to approximately 400 more women than men. However, even when women work at NGO's in order to create a voice and a space for women's empowerment, there are still gender discrepancies amongst the women. For example, in Uttar Predash in India, there is a NGO where women work. Marginalized because of their caste and religion, this organization has the opportunity to provide a voice to the voiceless and expose the issues that are happening. However, women from a higher caste still have issues eating the food of women from a lower caste.[26] This tension shows that there are still fundamental gender inequality issues that working at an NGO cannot readily solve.

Gender stereotypes

Cultural stereotypes are engrained in both men and women and these stereotypes are a possible explanation for gender inequality and the resulting gendered wage disparity. Women have traditionally been viewed as being caring and nurturing and are designated to occupations which require such skills. While these skills are culturally valued, they were typically associated with domesticity, so occupations requiring these same skills are not economically valued. Men have traditionally been viewed as the breadwinner or the worker, so jobs held by men have been historically economically valued and occupations predominated by men continue to be economically valued and pay higher wages.[4]

Sexism and discrimination

Gender inequality can further be understood through the mechanisms of sexism. Discrimination takes place in this manner as men and women are subject to prejudicial treatment on the basis of gender alone. Sexism occurs when men and women are framed within two dimensions of social cognition.

Discrimination also plays out with networking and in preferential treatment within the economic market. Men typically occupy positions of power within the job economy. Due to taste or preference for other men because they share similar characteristics, men in these positions of power are more likely to hire or promote other men, thus discriminating against women.[4]

Discrimination against men in the workplace is rare but does occur, particularly in health care professions. Only an estimated 0.4% of midwives in the UK are male and according to cbs only 1% of all trainee nurses and only 2% of Secretaries are male.

Discrimination against women in the workplace also occurs. Only an estimated 1% of roofers in the US are female.

Variations by country or culture

Gender inequality is a result of the persistent discrimination of one group of people based upon gender and it manifests itself differently according to race, culture, politics, country, and economic situation. It is furthermore considered a causal factor of violence against women. While gender discrimination happens to both men and women in individual situations, discrimination against women is an entrenched, global pandemic. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, rape and violence against women and girls is used as a tool of war.[27] In Afghanistan, girls have had acid thrown in their faces for attending school.[28] Considerable focus has been given to the issue of gender inequality at the international level by organizations such as the United Nations (UN), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the World Bank, particularly in developing countries. The causes and effects of gender inequality vary by country, as do solutions for combating it.

Asia

Many Malay Muslim communities believe that passion and desire carry derogatory connotations, especially when it is applied to humans.[29] The Muslim Malays believe that women have more sexual passion than men and that men have more logic.

One example of the continued existence of gender inequality in Asia is the “missing girls” phenomenon. It is estimated that due to the undervaluing of women, over 100 million males are living as a result of the infanticide of female children, sex selection for boys, allocation of economic and nutritional resources that are taken away from female children, and generalized violence.[30]

India

Some studies have documented that in villages in India, women are often discouraged to seek education, which is seen as immoral.[31] However, recent studies document remarkable success in efforts to improve girls' primary education [32]. However, when it comes to secondary education, girls are still disadvantaged. Moreover, women's employment rates are still low and seem to have further declined in recent years [33]. Recent studies also document unequal access to and control over family resources for Indian women including control over land and bank accounts as well as severe limitations on their geographical mobility.

In the Sitapur district, there is an event which involves men destroying gudiyas (rag dolls) that their sisters made the night before the festival.[34] The long tradition reveals the embedded gender inequality within society. The bashing of the doll symbolizes the bashing of the spirit, to maintain control.

United States

The World Economic Forum measures gender equity through a series of economic, educational, and political benchmarks. It has ranked the United States as 19th (up from 31st in 2009) in terms of achieving gender equity.[35] In the U.S., women are more likely than men to live in poverty, earn less money for the same work, are more likely to be victims of intimate partner violence and rape, and have less of a political voice. The US Department of Labor has indicated that in 2009, “the median weekly earnings of women who were full-time wage and salary workers was…80 percent of men’s”.[36] The Department of Justice found that in 2009, “the percentage of female victims (26%) of intimate partner violence was about 5 times that of male victims (5%)”.[37] “The United States ranks 41st in a ranking of 184 countries on maternal deaths during pregnancy and childbirth, below all other industrialized nations and a number of developing countries”[38] and women only represent 20% of members of Congress.[35] Gender inequality is thus a widespread and ingrained social and public health issue in the United States.

Impact and counteractions

Gender inequality and discrimination is argued to cause and perpetuate poverty and vulnerability in society as a whole.[39] Household and intra-household knowledge and resources are key influences in individuals' abilities to take advantage of external livelihood opportunities or respond appropriately to threats.[39] High education levels and social integration significantly improve the productivity of all members of the household and improve equity throughout society. Gender Equity Indices seek to provide the tools to demonstrate this feature of poverty.[39]

Despite acknowledgement by institutions such as the World Bank that gender inequality is bad for economic growth, there are many difficulties in creating a comprehensive response.[40] It is argued that the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) fail to acknowledge gender inequality as a cross-cutting issue. Gender is mentioned in MDG3 and MDG5: MDG3 measures gender parity in education, the share of women in wage employment and the proportion women in national legislatures.[39] MDG5 focuses on maternal mortality and on universal access to reproductive health.[39] However, even these targets are significantly off-track.[40]

Addressing gender inequality through social protection programmes designed to increase equity would be an effective way of reducing gender inequality.[40] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute argue for the need to develop the following in social protection in order to reduce gender inequality and increase growth:[39]

- Community childcare to give women greater opportunities to seek employment;

- Support parents with the care costs (e.g. South African child/disability grants);

- Education stipends for girls (e.g. Bangladesh’s Girls Education Stipend scheme);

- Awareness-raising regarding gender-based violence, and other preventive measures, such as financial support for women and children escaping abusive environments (e.g. NGO pilot initiatives in Ghana);

- Inclusion of programme participants (women and men) in designing and evaluating social protection programmes;

- Gender-awareness and analysis training for programme staff;

- Collect and distribute information on coordinated care and service facilities (e.g. access to micro-credit and microentrepreneurial training for women); and

- Developing monitoring and evaluation systems that include sex-disaggregated data.

However, politics plays a central role in the interests, institutions and ideas that are needed to reshape social welfare and gender inequality in politics and society limits governments' ability to act on economic incentives.[40]

It is interesting to note that NGO's tend to protect women against gender inequality and Structural violence. During war, the opposing side targets women, raping and even killing them. This could be because women are associated with children and killing them prohibits there being a next generation of the enemy.[41]

Another opportunity to tackle gender inequality is presented by modern Information and communication technologies. In a carefully controlled study[42], it has been shown that women embrace digital technology more than men, disproving the stereotype of "technophobic women". Given that digital information and communication technologies have the potential to provide access to employment, education, income, health services, participation, protection, and safety, among others (ICT4D), the natural affinity of women with these new communication tools provide women with a tangible bootstrapping opportunity to tackle social discrimination. In other words, if women are provided with modern information and communication technologies, these digital tools present to them an opportunity to fight longstanding inequalities in the workplace and at home.

See also

- Affirmative action

- Discrimination

- Equal pay for women

- Feminism

- Gender and education

- Gender and suicide

- Gender differences

- Gender equality

- Gender inequality in Australia

- Girl Effect, The

- Global Gender Gap Report

- Intra-household bargaining

- Kenneth and Mamie Clark

- Kiva (organization)

- Marginalization

- Masculism

- Men's Rights

- Microinequity

- Obedient Wives Club

- Paycheck Fairness Act (in the US)

- Sex and psychology

- Sex segregation

- Sexism

- Sexual dimorphism

- Shared parenting

- Socialization

- World Bank

- Women's rights

References

- ^ a b c Wood, Julia. Gendered Lives. 6th. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2005.

- ^ a b Burstein, Paul. “Equal Employment Opportunity: Labor Market Discrimination and Public Policy.” Edison, NJ: Aldine Transaction, 1994.

- ^ Jacobs, Jerry. Gender Inequality at Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1995.

- ^ a b c d e Massey, Douglas. “Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System.” NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 2007.

- ^ a b Cotter, David, Joan Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman. The American People Census 2000: Gender Inequality at Work. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000.

- ^ Hurst, Charles, E. Social Inequality. 6th. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2007.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2009. Report 1025, June 2010.

- ^ Cotter, David, Joan Hermsen, Seth Ovadia and Reeve Vanneman. “Social Forces: The Glass Ceiling Effect.” Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- ^ Sherri Grasmuck and Rosario Espinal. "Market Success or Female Autonomy?" Sage Publications, Inc, 2000.

- ^ Women 'earn less than men across the globe', Vedior, 4 March 2008

- ^ Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. "On The Pill: Changing the course of women's education." The Milken Institute Review, Second Quarter 2001: p3.

- ^ Goldin, Claudia and Lawrence F. Katz. "The Power Of The Pill: Contraceptives And Women's Career And Marriage Decisions," Journal of Political Economy, 2002, v110 (4,Aug),p731.

- ^ http://www.catalyst.org/etc/Catalyst_Written_Testimony_To_JEC_With_Appendix.pdf

- ^ Goldin, Claudia. "The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women's Employment, Education, And Family," American Economic Review, 2006, v96(2,May), p13.

- ^ Zheng, Tiantian. Red Lights: the lives of sex workers in Postsocialist China.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009

- ^ Hekman, David R.; Aquino, Karl; Owens, Brad P.; Mitchell, Terence R.; Schilpzand, Pauline; Leavitt, Keith. (2009) An Examination of Whether and How Racial and Gender Biases Influence Customer Satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal. http://journals.aomonline.org/inpress/main.asp?action=preview&art_id=610&p_id=1&p_short=AMJ

- ^ Bakalar, Nicholas (2009) “A Customer Bias in Favor of White Men.” New York Times. June 23, 2009, page D6. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/health/research/23perc.html?ref=science

- ^ Vedantam, Shankar (2009) “Caveat for Employers.” Washington Post, June 1, 2009, page A8 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/05/31/AR2009053102081.html

- ^ Jackson, Derrick (2009) “Subtle, and stubborn, race bias.” Boston Globe, July 6, 2009, page A10 http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/editorials/articles/2009/07/06/subtle_and_stubborn_race_bias/

- ^ National Public Radio, Lake Effect, http://www.wuwm.com/programs/lake_effect/view_le.php?articleid=754

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kenneth_and_Mamie_Clark

- ^ Vianello, Mino, and Renata Siemienska. Gender Inequality: A Comparative Study of Discrimination and Participation. Newbury Park, California: SAGE Publications Ltd., 1990.

- ^ Friedman, Ellen, and Jennifer Marshall. Issues of Gender. New York: Pearson Education, Inc. , 2004.

- ^ The mama lion at the gate - Salon.com

- ^ Eszter Hargittai, What Causes Variation in Contributing to Participatory Web Sites?

- ^ Sangtin Writers Collective and Richa Nagar, Playing with Fire: Feminist Thought and Activism through Seven Lives in India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (October 7, 2007). "Rape Epidemic Raises Trauma of Congo War". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Filins, Dexter (August 23, 2009). "A School Bus for Shamsia". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ Peletz,Michael G. Gender, Sexuality and Body Politics in Modern Asia. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, 2011.

- ^ Kristoff, Nicholas D. [2011 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/23/magazine/23Women-t.html "The Women's Crusade"]. New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Sangtin Writers Collective and Richa Nagar, Playing with Fire: Feminist Thought and Activism through Seven Lives in India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006, p. 23

- ^ Desai, S. et al, 2010, Human Development in India: Challenges for a Society in Transition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- ^ National Sample Survey Office (2011). Employment and Unemployment Situation in India 2009-2010. New Delhi, National Statistical Organisation, Government of India.

- ^ Sangtin Writers Collective and Richa Nagar, Playing with Fire: Feminist Thought and Activism through Seven Lives in India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

- ^ a b World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report. 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Quick Stats on Women Workers". U.S. Department of Labor.

- ^ "National Crime Victimization Survey, 2010". Bureau of Justice Statistics.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "CEDAW 2011 website". Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicola Jones, Rebecca Holmes, Jessica Espey 2008. Gender and the MDGs: A gender lens is vital for pro-poor results. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ a b c d Nicola Jones and Rebecca Holmes 2010. Gender, politics and social protection. London: Overseas Development Institute

- ^ Michael G. Peletz, Gender, Sexuality and Body Politics in Modern Asia. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, 2011.

- ^ "Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics ", Martin Hilbert (2011), Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(6), 479-489; free access to the study here: martinhilbert.net/DigitalGenderDivide.pdf