Alternative medicine

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

| Alternative medicine | |

|---|---|

| MeSH | D000529 |

Alternative medicine is any of a wide range of health care practices, products, and therapies not typically included in the degree courses of established medical schools. Examples include homeopathy, Ayurveda, chiropractic, and acupuncture.

Complementary medicine is what alternative medicine is called when used together with science-based medicine, in a belief that it increases the effectiveness, or "complements", the science-based medical treatment.[1][2][3] CAM is the abbreviation for Complementary and alternative medicine.[4][5] Integrative medicine (or integrative health) is the combination of the practices and methods of alternative medicine with evidence-based medicine.[6]

Regulation and licensing of alternative medicine varies from country to country.

The term alternative medicine is used in information issued by public bodies in the United States of America.[7] and the United Kingdom[8] The extension of the term "medicine" in that way has been criticised on the grounds that the products or practices to which "alternative medicine" is applied fail to satisfy the criteria of evidence-based medicine.

Introduction, controversy in principle

Use of the term "alternative medicine" has been the subject of discussion in some leading medical journals published in Australia, Great Britain and North America.[9][10][11]

Critics say the expression “alternative medicine” is deceptive because it implies there is an effective alternative to science-based medicine, when there is not. They say the term “complementary” is deceptive because the word implies that the treatment increases the effectiveness of (complements) science-based medicine, when it does not.[5][20][21][22] Despite such objections, some fields of alternative practice are regulated in a manner similar to that governing evidence-based medicine, and others have no regulation.

Alternative medicine is put forward as having the healing effects of medicine, but is not based on evidence gathered with the scientific method.[12] Alternative medicine is usually based on religion, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural energies, pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, or fraud.[13][14][15][16] Alternative therapies typically lack any scientific validation, and their effectiveness is either unproved or disproved.[14][17][18] The treatments are those that are not part of the conventional, science-based healthcare system.[19][20][21][22]

Critics say the expression “alternative medicine” is deceptive because it implies there is an effective alternative to science-based medicine, when there is not. They say the term “complementary” is deceptive because the word implies that the treatment increases the effectiveness of (complements) science-based medicine, when it does not.[14][23][24][25] Despite such objections, some fields of alternative practice are regulated in a manner similar to that governing evidence-based medicine, and others have no regulation. Regulation and licensing of alternative medicine varies from country to country, and state to state.

Alternative medicine practices and beliefs are diverse in their foundations and methodologies. Methods may incorporate or base themselves on traditional medicine, folk knowledge, spiritual beliefs, ignorance or misunderstanding of scientific principles, errors in reasoning, or newly conceived approaches claiming to heal.[14][15][26] Prayer to heal is the most common alternative medicine in many western countries, and faith healing is a part of many religions. Some believe that meditation affects health. Yoga as a healing practice involves stretching, exercise and meditation related to the Hindu religion, and makes claims to healing in the spiritual realm. Traditional Chinese medicine and the Ayurvedic medicine of India are complex systems developed over thousands of years, both based on regional supernatural belief systems and traditional use of herbs and other substances. Acupuncture is a part of Traditional Chinese medicine in which needles are inserted in the body to alter the flow of supernatural energy believed to propel the blood and influence health. Chiropractic manipulation of the spine was developed in the United States, and involves manipulating the spine to influence supernatural energies believed to cause disease. Homeopathy was developed in Europe before the existence of science of chemistry, which has subsequently proven the premises of homeopathy to be false. Magnets and light are used in therapies based on a misunderstanding of electricity and magnetism. Dietary supplements that are unproven by science are considered alternative medicines. African, Caribbean, Pacific Island, Native American, and other regional cultures have traditional medical systems as diverse as their diversity of cultures.[19]

Many of the claims regarding the efficacy of alternative medicines are controversial. Research on alternative medicine is frequently of low quality and methodologically flawed.[27] The safety of alternative medicine is also controversial. Some alternative treatments have been associated with unexpected side effects, which can be fatal. Where alternative treatments are used in place of conventional science-based medicine, even with the very safest alternative medicines, failure to use or delay in using conventional science-based medicine has resulted in deaths.[28][29] Many voluntary health agencies focused upon health fraud, misinformation, and quackery as public health problems, are highly critical of alternative medicine.[30] That alternative medicine is on the rise "in countries where Western science and scientific method generally are accepted as the major foundations for healthcare, and 'evidence-based' practice is the dominant paradigm" has been described as an "enigma" in the Medical Journal of Australia.[31]

Examples and classes of alternative medicines

The term complementary and alternative medicine refers to a wide range of treatments and practices. The following examples include some of the more common methods in use. Most therapies can be considered as part of five broad classes; biological based approaches, energy therapies, alternative medical systems, muscle and joint manipulation and mind body therapies.

Biological approaches include the use of herbal medicines, special diets or very high doses of vitamins. Energy therapies are designed to influence energy fields (biofields) that practitioners believe surround and enter the body. Some energy therapies involve the use of crystals, while others use magnets and electric fields. Body-based therapies such as massage, chiropractic and osteopathy use movement and physical manipulation of joints and muscles. Mind–body therapies attempt to use the mind to affect bodily symptoms and functions; examples include yoga, spirituality and relaxation. Alternative medical systems are complete health systems with their own approaches to diagnosis and treatment that differ from the conventional biomedical approach to health. Some are cultural systems such as Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine, while others, such as Homeopathy and Naturopathy are relatively recent and were developed in the West.[18]

Alternative Medical Systems

Complete medical systems can be based on traditional ethinic practices, or an underlying belief system.Traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda are examples of the former while Homeopathy and Naturopathy are examples of the later.[19]

Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurvedic medicine is a traditional medicine of India. It includes a belief that healing can be done through use of traditional herbs and having the spiritual balance of the religions of Hinduism and Buddhism. For example, by not suppressing natural urges of food intake, sleep, and sexual intercourse, and at the same time by not overindulging in them, but to keep them in balance. Ayurveda stresses the use of plant-based medicines and treatments, with some animal products, and added minerals, including sulfur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate. Safety concerns have been raised about Ayurveda, with two U.S. studies finding about 20 percent of Ayurvedic Indian-manufactured patent medicines contained toxic levels of heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic. Other concerns include the use of herbs containing toxic compounds and the lack of quality control in Ayurvedic facilities. Incidents of heavy metal poisoning have been attributed to the use of these compounds in the United States.[32][33][34][35][36][37][38]

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese Medicine is a combination of traditional practices and beliefs developed over thousands of years in China, together with modifications made by the Communist party. Common practices include herbal medicine, acupuncture (insertion of needles in the body at specified points, massage (Tui na), exercise (qigong), and dietary therapy. The practices are based on belief in a supernatural energy called qi, considerations of Chinese Astrology and Chinese numerology, traditional use of herbs and other substances found in China, a belief that a map of the body is contained on the tongue which reflects changes in the body, and an incorrect model of the anatomy and physiology of internal organs.[14][39][40][41][42][43]

The Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong, in response to the lack of modern medical practitioners, revived acupuntcute and its theory was rewritten to adhere to the political, economic and logistic necessities of providing for the medical needs of China's population.[44] In the 1950s the "history" and theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine was rewritten as communist propoganda, at Mao's insistence, to correct the supposed "bourgeois thought of Western doctors of medicine" (p. 109).[45] Acupuncture gained attention in the United States when President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972, and the delegation was shown a patient undergoing major surgery while fully awake, ostensibly receiving acupuncture rather than anesthesia. Later it was found that the patients selected for the surgery had both a high pain tolerance and received heavy indoctrination before the operation; these demonstration cases were also frequently receiving morphine surreptitiously through an intravenous drip that observers were told contained only fluids and nutrients.[39]

Homeopathy

Whole medical systems can be based on a common belief systems that underly the system of practices and methods, such as in Naturopathy or Homeopathy.[19]

Homeopathy is a system developed in a belief that a substance that causes the symptoms of a disease in healthy people will cure similar symptoms in sick people.[46] It was developed before knowledge of the existence of atoms and molecules, and of basic chemistry, which showed that the repeated dilutions of the substance in homeopathy produced only water, and so homeopathy was false.[47][48][49][50] Within the medical community homeopathy is now considered to be quackery.[51]

Naturopathy

Naturopathic medicine is based on a belief that the body heals itself using a supernatural vital energy that guides bodily processes,[52] a view in conflict with the paradigm of evidence-based medicine.[53] Many naturopaths have opposed vaccination,[54] and "scientific evidence does not support claims that naturopathic medicine can cure cancer or any other disease".[55]

Energy Therpaies

Bases of belief may include belief in existence of supernatural energies undetected by the science of physics, as in biofields, or in belief in properties of the energies of physics that are inconsistent with the laws of physics, as in energy medicine.[19]

Biofields

Biofield therapies are intended to influence energy fields that, it is purported, surround and penetrate the body.[19] Writers such as noted astrophysicist and advocate of skeptical thinking (Scientific skepticism) Carl Sagan (1934-1996) have described the lack of empirical evidence to support the existence of the putative energy fields on which these therapies are predicated.[56]

Acupuncture is a component of Traditional Chinese Medicine. In acupuncture, it is believed that a supernatural energy called qi flows through the universe and through the body, and helps propel the blood, blockage of which leads to disease.[40] It is believed that insertion of needles at various parts of the body determined by astrological calculations can restore balance to the blocked flows, and thereby cure disease.[40]

Chiropractic was developed in the belief that manipulating the spine affects the flow of a supernatural vital energy and thereby affects health and disease.

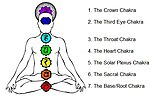

In the western version of Japanese Reiki, the palms are placed on the patient near Chakras, believed to be centers of supernatural energies, in a belief that the supernatural energies can transferred through the palms of the practitioner, to heal the patient.

Electromagnetic Fields

Bioelectromagnetic-based therapies use verifiable electromagnetic fields, such as pulsed fields, alternating-current, or direct-current fields in an unconventional manner.[19] Magnetic healing does not claim existence of supernatural energies, but asserts that magnets can be used to defy the laws of physics to influence health and disease.

Mind Body Therapies

Mind-body medicine takes a holistic approach to health that explores the interconnection between the mind, body, and spirit. It works under the premise that the mind can affect "bodily functions and symptoms".[19] Mind body medicines includes healing claims made in yoga, meditation, deep-breathing exercises, guided imagery, hypnotherapy, progressive relaxation, qi gong, and tai chi.[19]

Yoga, a method of traditional stretches, excercises, and meditations in Hinduism, may also be classified as an energy medicine insofar as its healing effects are believed by to be due to a healing "life energy" that is absorbed into the body through the breath, and is thereby believed to treat a wide variety of illnesses and complaints.[57]

Religion based healing practices, such as use of prayer and the laying of hands in Christian faith healing, rely on belief in divine intervention for healing.

Herbs, Diet and Vitamins

Substance based practices use substances found in nature such as herbs, foods, non-vitamin supplments and megavitmins, and minerals, and includes traditional herbal remedies with herbs specific to regions in which the cultural practices arose.[19] "Herbal" remedies in this case, may include use of nonherbal toxic chemicals from a nonbiological sources, such as use of the poison lead in Traditional Chinese Medicine.[58] Nonvitamin supplements include fish oil, Omega-3 fatty acid, glucosamine, echinacea, flaxseed oil or pills, and ginseng, when used under a claim to have healing effects.[58]

Body manipulation

Manipulative and body-based practices feature manipulation or movement of body parts, such as is done in chiropractic manipulation.

Criticism

Scientists and others have criticized complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) on a number of grounds. The name "alternative medicine" has been criticized as being an invention to deliberately mislead sick people into thinking there is an effective alternative to science based medicine. The science community criticizes CAM on the grounds that it is ineffective, is based on ignorance of basic science, is based on incorrect reasoning, and refuses to admit to when it is disproved. It has been criticized as being unethical and used for fraud. There is criticism that it takes research funds from testing more scientifically plausible methods. Integrative medicine has been criticized in that its practitioners, trained in science based medicine, deliberately mislead patients by pretending placebos are not. "Quackademic medicine" is a pejorative term used for “integrative medicine”, which is considered to be an infiltration of quackery into academic science-based medicine.[25]

Misleading use of terminology

Proponents of alternative medicine often use terminology which is loose or ambiguous to create the appearance that a choice between "alternative" effective treatments exists when it does not, that there is effectiveness or scientific validity when it does not exist, to suggest that a dichotomy exists when it does not, or to suggest that consistency with science exists when it may not. The term "alternative" is to suggest that a patient has a choice between effective treatments when there is not. The use of the word "conventional" or "mainstream" is to suggest that the difference between alternative medicine and science based medicine is the prevalence of use, rather than lack of a scientific basis of alternative medicine as compared to "conventional" or "mainstream" science based medicine. The use of the term "complementary" is to suggest that purported supernatural energies of alternative medicine can add to or complement science based medicine. The use of "Western medicine" and "Eastern medicine" is to suggest that the difference is not between evidence based medicine and treatments which don't work, but a cultural difference between the Asiatic east and the European west. The use of the term "integrative" is to suggest that supernatural beliefs can be consistently integrated with science and the result has scientific validity.[59]

"Alternative medicine" refers to any practice that is put forward as having the healing effects of medicine, but is not based on evidence gathered with the scientific method,[13] when used independently or in place of medicine based on science.[19][60][61][62] "Complementary medicine" refers to use of alternative medicine alongside conventional science based medicine, in the belief that it increases the effectiveness.[19][60][61] "CAM" is an abbreviation for "complementary and alternative medicine". "Integrative medicine" ("integrated medicine") is used either to refer to a belief that medicine based on science can be "integrated" with practices that are not, or that a combination of alternative medical treatments with conventional science based treatments that have some scientific proof of efficacy, in which case it is identical with CAM.[6] “Whole medical systems” either refers to a spiritual belief, that “spiritual wholeness” is the root of physiological and physical well-being,[63] Ayurveda, Chinese medicine, Homeopathy and Naturopathy are cited as examples[64] or to differentiate widely comprehensive systems from either specific components of the system or from practices that claim to heal only a limited kind of specific medical conditions.

There is a debate among medical researchers over whether any therapy may be properly classified as 'alternative medicine'. Some claim that there is only medicine that has been adequately tested and that which has not.[65] "There really is no such thing as alternative medicine--only medicine that has been proved to work and medicine that has not." - Arnold Relman, editor in chief emeritus of The New England Journal of Medicine.[66][full citation needed] Speaking of government funding studies of integrating alternative medicine techniques into the mainstream, Steven Novella, a neurologist at Yale School of Medicine wrote that it "is used to lend an appearance of legitimacy to treatments that are not legitimate." Marcia Angell, former executive editor of The New England Journal of Medicine says, "It's a new name for snake oil."[67] They feel that healthcare practices should be classified based solely on scientific evidence. If a treatment has been rigorously tested and found safe and effective, science based medicine will adopt it regardless of whether it was considered "alternative" to begin with.[65] It is thus possible for a method to change categories (proven vs. unproven), based on increased knowledge of its effectiveness or lack thereof. Prominent supporters of this position include George D. Lundberg, former editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).[68]

Criticism on scientific grounds

An editorial in the Economist characterized alternative medicine as mostly "quackery" and described the vast majority as offering nothing more than the placebo effect (the effect of taking a sugar pill and thinking it is medicine). It suggested that, "Virtually all alternative medicine is bunk; but the placebo effect is rather interesting."[69]

Stanford University medical professor Wallace Sampson, former chairperson of the National Council Against Health Fraud, advisor to the California Attorney General and numerous district attorneys on medical fraud, and editor of Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, writes that CAM is the "propagation of the absurd". He argues that alternative and complementary have been substituted for quackery, dubious and implausible.[70]

Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, defines alternative medicine as a "set of practices that cannot be tested, refuse to be tested, or consistently fail tests."[71] He also states that "there is no alternative medicine. There is only medicine that works and medicine that doesn't work."[72] He says that if a technique is demonstrated effective in properly performed trials, it ceases to be alternative and simply becomes medicine.[73]

Based on incorrect reasoning

A letter by four Nobel Laureates and other prominent scientists deplored the lack of critical thinking in research on alternative medicine that was supprted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).[74]

Based on ignorance of basic scientific facts

In 2009 a group of scientists made a proposal to shut down the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. They argued that the vast majority of studies were based on fundamental misunderstandings of physiology and disease, and have shown little or no effect.[75]

Ineffective and misleading statements on efficacy

The United States' National Science Foundation has defined alternative medicine as "all treatments that have not been proven effective using scientific methods."[13] Proponents of an evidence-base for medicine, such as the Cochrane Collaboration take a position that all treatments, whether "mainstream" or "alternative", ought to be held to the standards of the scientific method.[76] Stephen Barrett, founder and operator of Quackwatch, argues that practices labeled "alternative" should be reclassified as either genuine, experimental, or questionable. Here he defines genuine as being methods that have sound evidence for safety and effectiveness, experimental as being unproven but with a plausible rationale for effectiveness, and questionable as groundless without a scientifically plausible rationale.[77] Edzard Ernst, a professor of complementary medicine, characterizes the evidence for many alternative techniques as weak, nonexistent, or negative.[78] Ernst has concluded that 95% of the alternative treatments he and his team have studied, including acupuncture, herbal medicine, homeopathy, and reflexology, are, according to The Economist, "statistically indistinguishable from placebo treatments."[79]

Unfalsifiable

Wallace Sampson points out that CAM tolerates contradiction without thorough reason and experiment.[70] Steven Barrett points out that there is a policy at the NIH of never saying something doesn't work only that a different version or dose might give different results.[80]

Using plausibility of one practice to support implausible other practices

Steven Barrett also expressed concern that, just because some "alternatives" have merit, there is the impression that the rest deserve equal consideration and respect even though most are worthless, since they are all classified under the one heading of alternative medicine.[77] A group of prominent scientists argued before the federal government that plausibility of interventions such as diet, relaxation, yoga and botanical remedies, should not be used to support research on implausible interventions based on superstition and belief in the supernatural, and that the plausible methods can be studied just as well in other parts of NIH, where they should be made to compete on an equal footing with other research projects.[75]

Taking resources from real medical research, abuse of medical authority

The NCCAM budget has been criticized[67] because, despite the duration and intensity of studies to measure the efficacy of alternative medicine, there had been no effective CAM treatments supported by scientific evidence as of 2002 according to the QuackWatch website.[81] Despite this, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine budget has been on a sharp sustained rise to support complementary medicine. In fact, the whole CAM field has been called by critics the SCAM.[81]

There have been negative results in almost all studies conducted over ten years at a cost of $2.5 billion by the NCCAM.[82] R. Barker Bausell, a research methods expert and author of "Snake Oil Science" states that "it's become politically correct to investigate nonsense."[80] There are concerns that just having NIH support is being used to give unfounded "legitimacy to treatments that are not legitimate."[75]

Use of placebos in order to achieve a placebo effect in integrative medicine has been criticized as “diverting research time, money, and other resources from more fruitful lines of investigation in order to pursue a theory that has no basis in biology”.[25][83]

Ethics, dangerous misinformation, fraud

Speaking of ethics, in November 2011 Edzard Ernst stated that the "level of misinformation about alternative medicine has now reached the point where it has become dangerous and unethical. So far, alternative medicine has remained an ethics-free zone. It is time to change this."[84] Ernst requested that Prince Charles recall two guides to alternative medicine published by the Foundation for Integrated Health, on the grounds that "[t]hey both contain numerous misleading and inaccurate claims concerning the supposed benefits of alternative medicine" and that "[t]he nation cannot be served by promoting ineffective and sometimes dangerous alternative treatments."[85] In general, he believes that CAM can and should be subjected to scientific testing.[76][78][86] Ernst requested that Prince Charles recall two guides to alternative medicine published by the Foundation for Integrated Health, on the grounds that "[t]hey both contain numerous misleading and inaccurate claims concerning the supposed benefits of alternative medicine" and that "[t]he nation cannot be served by promoting ineffective and sometimes dangerous alternative treatments".[76][78][85][86]

Marketing is part of the medical training required in chiropractic educaion, and propoganda methods in alternative medicine have been traced back to those used by Hitler and Goebels in their promotion of pseudoscience in medicine.[14][87]

Integrative medicine practitioners intentionally mislead patients

Academic proponents of integrative medicine sometimes recommend misleading patients by using known placebo treatments in order to achieve a placebo effect.[88] However, a 2010 survey of family physicians found that 56% of respondents said they had used a placebo in clinical practice as well. Eighty-five percent of respondents believed placebos can have both psychological and physical benefits.[89][90]

Use and regulation

Prevalence of use

About 50% of people in developed countries use some kind of complementry and alternative medicine other than prayer for health.[91][92][93][94] About 40% of cancer patients use some form of CAM.[95] The use of alternative medicine in developed countries is increasing,[13][96][97] with a 50 percent increase in expenditures and a 25 percent increase in the use of alternative therapies between 1990 and 1997 in America.[98] Americans spend many billions on the therapies annually.[98] Most Americans used CAM to treat and/or prevent musculoskeletal conditions or other conditions associated with chronic or recurring pain.[92] In America, women were more likely than men to use CAM., with the biggest difference in use of mind-body therapies including prayer specifically for health reasons".[92] In 2008, more than 37% of American hospitals offered alternative therapies, up from 26.5 percent in 2005, and 25% in 2004.[99][100] More than 70% of the hospitals offering CAM were in urban areas.[100]

The phenomena of how alternative medicine can be on the rise “in countries where Western science and scientific method generally are accepted as the major foundations for healthcare, and ‘evidence-based’ practice is the dominant paradigm" has been described as an "enigma" in the Medical Journal of Australia.[31] Use of alternative therapies was found to be higher among those who had attended college and had higher incomes.[98] A survey of Americans found that 88 percent agreed that "there are some good ways of treating sickness that medical science does not recognize".[13] Use of magnets was the most common tool in energy medicine in America, and among users of it, 58 percent described it as at least “sort of scientific”, when it is not at all scientific.[13] In 2002, at least 60 percent of US medical schools have at least some class time spent teaching alternative therapies.[13] "Therapeutic touch," was taught at more than 100 colleges and universities in 75 countries before the practice was debunked by a nine-year-old child for a school science project.[13][13][101] In Austria and Germany complementary and alternative medicine is mainly in the hands of doctors with MDs,[4] and half or more of the American alternative practitioners are licensed MDs.[102] In Germany herbs are tightly regulated: half are prescribed by doctors and covered by health insurance.[103]

In developing nations, access to essential medicines is severely restricted by lack of resources and poverty. Traditional remedies, often closely resembling or forming the basis for alternative remedies, may comprise primary healthcare or be integrated into the healthcare system. In Africa, traditional medicine is used for 80% of primary healthcare, and in developing nations as a whole over one-third of the population lack access to essential medicines.[104]

A 1997 survey found that 13.7% of respondents in the United States had sought the services of both a medical doctor and an alternative medicine practitioner. The same survey found that 96% of respondents who sought the services of an alternative medicine practitioner also sought the services of a medical doctor in the past 12 months. Medical doctors are often unaware of their patient's use of alternative medical treatments as only 38.5% of the patients alternative therapies were discussed with their medical doctor.[96] A British telephone survey by the BBC of 1209 adults in 1998 shows that around 20% of adults in Britain had used alternative medicine in the past 12 months.[105]

Prevalence of use of specific therapies

The most common CAM therapies used in the US in 2002 were prayer (45.2%), herbalism (18.9%), breathing meditation (11.6%), meditation (7.6%), chiropractic medicine (7.5%), yoga (5.1%-6.1%), body work (5.0%), diet-based therapy (3.5%), progressive relaxation (3.0%), mega-vitamin therapy (2.8%) and Visualization (2.1%)[92][106]

In Britain, the most often used alternative therapies were Alexander technique, Aromatherapy, Bach and other flower remedies, Body work therapies including massage, Counselling stress therapies, hypnotherapy, Meditation, Reflexology, Shiatsu, Ayurvedic medicine, Nutritional medicine, and Yoga.[107]

According to the National Health Service (England), the most commonly used complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) supported by the NHS in the UK are: acupuncture, aromatherapy, chiropractic, homeopathy, massage, osteopathy and clinical hypnotherapy.[108]

"Complementary medicine treatments used for pain include: acupuncture, low-level laser therapy, meditation, aroma therapy, Chinese medicine, dance therapy, music therapy, massage, herbalism, therapeutic touch, yoga, osteopathy, chiropractic, naturopathy, and homeopathy."[109]

Palliative care

Complementary therapies are often used in palliative care or by practitioners attempting to manage chronic pain in patients. Complementary medicine is considered more acceptable in the interdisciplinary approach used in palliative care than in other areas of medicine. "From its early experiences of care for the dying, palliative care took for granted the necessity of placing patient values and lifestyle habits at the core of any design and delivery of quality care at the end of life. If the patient desired complementary therapies, and as long as such treatments provided additional support and did not endanger the patient, they were considered acceptable."[110] The non-pharmacologic interventions of complementary medicine can employ mind-body interventions designed to "reduce pain and concomitant mood disturbance and increase quality of life."[111]

Regulation

Some fields of alternative practice are regulated in a manner similar to that governing science-based medicine, and some have no regulation at all. Regulation and licensing of alternative medicine ranges widely from country to country, and state to state.

Government bodies in the USA and elsewhere have published information or guidance about alternative medicine. One of those is the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which mentions specifically homeopathic products, traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic products.[112] A document which the FDA has issued for comment is headed Guidance for Industry: Complementary and Alternative Medicine Products and Their Regulation by the Food and Drug Administration, last updated 04/06/2012.[113] The document opens with three preliminary paragraphs which explain that in the document:

- - "complementary and alternative medicine" (CAM) are being used to encompass a wide array of health care practices, products, and therapies which are distinct from those used in "conventional" or "allopathic" medicine.

- - some forms of CAM, such as traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic medicine, have been practiced for centuries, and others, such as electrotherapy, are of more recent origin.

- - in a publication of The Institute of Medicine it has been stated that more than one-third of American adults reported using some form of CAM and that visits to CAM providers each year exceed those to primary care physicians (Institute of Medicine, Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States, pages 34-35, 2005).

- - no mention (in the document) of a particular CAM therapy, practice or product should be taken as expressing FDA's support or endorsement of it or as an agency determination that a particular product is safe and effective.

Efficacy

Alternative therapies lack scientific validation, and their effectiveness is either unproved or disproved.[13][14][17][18] Many of the claims regarding the efficacy of alternative medicines are controversial, since research on them is frequently of low quality and methodologically flawed.[27] Selective publication of results (misleading results from only publishing postive results, and not all results), marked differences in product quality and standardisation, and some companies making unsubstantiated claims, call into question the claims of efficacy of isolated examples where herbs may have some evidence of containing chemicals that may affect health.[114] The Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine points to confusions in the general population - a person may attribute symptomatic relief to an otherwise-ineffective therapy just because they are taking something (the placebo effec); the natural recovery from or the cyclical nature of an illness (the regression fallacy) gets misattributed to an alternative medicine being taken; a person not diagnosed with science based medicine may never originally have had a true illness diagnosed as an alternative disease category.[115]

Testing

In 2003, a project funded by the CDC identified 208 condition-treatment pairs, of which 58% had been studied by at least one randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 23% had been assessed with a meta-analysis.[116] According to a 2005 book by a US Institute of Medicine panel, the number of RCTs focused on CAM has risen dramatically. The book cites Vickers (1998), who found that many of the CAM-related RCTs are in the Cochrane register, but 19% of these trials were not in MEDLINE, and 84% were in conventional medical journals.[27]: 133

As of 2005, the Cochrane Library had 145 CAM-related Cochrane systematic reviews and 340 non-Cochrane systematic reviews. An analysis of the conclusions of only the 145 Cochrane reviews was done by two readers. In 83% of the cases, the readers agreed. In the 17% in which they disagreed, a third reader agreed with one of the initial readers to set a rating. These studies found that, for CAM, 38.4% concluded positive effect or possibly positive (12.4%) effect, 4.8% concluded no effect, 0.69% concluded harmful effect, and 56.6% concluded insufficient evidence. An assessment of conventional treatments found that 41.3% concluded positive or possibly positive effect, 20% concluded no effect, 8.1% concluded net harmful effects, and 21.3% concluded insufficient evidence. However, the CAM review used the 2004 Cochrane database, while the conventional review used the 1998 Cochrane database.[27]: 135–136

Lists of the Cochrane Reviews on alternative medicine including summaries of the results sorted by type of therapy (updated monthly) are made available at ViFABs (Knowledge and Research Center for Alternative Medicines) home page, see the lists here: http://www.vifab.dk/uk/cochrane+and+alternative+medicine

Most alternative medical treatments are not patentable, which may lead to less research funding from the private sector. In addition, in most countries, alternative treatments (in contrast to pharmaceuticals) can be marketed without any proof of efficacy—also a disincentive for manufacturers to fund scientific research.[117] Some have proposed adopting a prize system to reward medical research.[118] However, public funding for research exists. Increasing the funding for research on alternative medicine techniques is the purpose of the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. NCCAM and its predecessor, the Office of Alternative Medicine, have spent more than $2.5 billion on such research since 1992; this research has largely not demonstrated the efficacy of alternative treatments.[80][119][120]

In the same way as for conventional therapies, drugs, and interventions, it can be difficult to test the efficacy of alternative medicine in clinical trials. In instances where an established, effective, treatment for a condition is already available, the Helsinki Declaration states that withholding such treatment is unethical in most circumstances. Use of standard-of-care treatment in addition to an alternative technique being tested may produce confounded or difficult-to-interpret results.[121]

Cancer researcher Andrew J. Vickers has stated:

- Contrary to much popular and scientific writing, many alternative cancer treatments have been investigated in good-quality clinical trials, and they have been shown to be ineffective. In this article, clinical trial data on a number of alternative cancer cures including Livingston-Wheeler, Di Bella Multitherapy, antineoplastons, vitamin C, hydrazine sulfate, Laetrile, and psychotherapy are reviewed. The label "unproven" is inappropriate for such therapies; it is time to assert that many alternative cancer therapies have been "disproven."[122]

Safety

Adequacy of Regulation and CAM Safety

One of the commonly voiced concerns about complementary alternative medicine (CAM) is the manner in which is regulated. There have been significant developments in how CAMs should be assessed prior to re-sale in the United Kingdom and the European Union (EU) in the last 2 years. Despite this, it has been suggested that current regulatory bodies have been ineffective in preventing deception of patients as many companies have re-labelled their drugs to avoid the new laws.[123] There is no general consensus about how to balance consumer protection (from false claims, toxicity, and advertising) with freedom to choose remedies.

Advocates of CAM suggest that regulation of the industry will adversely affect patients looking for alternative ways to manage their symptoms, even if many of the benefits may represent the placebo affect.[124] Some contend that alternative medicines should not require any more regulation than over-the-counter medicines that can also be toxic in overdose (such as paracetamol).[125]

Interactions with conventional pharmaceuticals

Forms of alternative medicine that are biologically active can be dangerous even when used in conjunction with conventional medicine. Examples include immuno-augmentation therapy, shark cartilage, bioresonance therapy, oxygen and ozone therapies, insulin potentiation therapy. Some herbal remedies can cause dangerous interactions with chemotherapy drugs, radiation therapy, or anesthetics during surgery, among other problems.[126] An anecdotal example of these dangers was reported by Associate Professor Alastair MacLennan of Adelaide University, Australia regarding a patient who almost bled to death on the operating table after neglecting to mention that she had been taking "natural" potions to "build up her strength" before the operation, including a powerful anticoagulant that nearly caused her death.[127]

To ABC Online, MacLennan also gives another possible mechanism:

- And lastly [sic] there's the cynicism and disappointment and depression that some patients get from going on from one alternative medicine to the next, and they find after three months the placebo effect wears off, and they're disappointed and they move on to the next one, and they're disappointed and disillusioned, and that can create depression and make the eventual treatment of the patient with anything effective difficult, because you may not get compliance, because they've seen the failure so often in the past.|[128]

Potential side-effects

Conventional treatments are subjected to testing for undesired side-effects, whereas alternative treatments, in general, are not subjected to such testing at all. Any treatment – whether conventional or alternative – that has a biological or psychological effect on a patient may also have potential to possess dangerous biological or psychological side-effects. Attempts to refute this fact with regard to alternative treatments sometimes use the appeal to nature fallacy, i.e., "that which is natural cannot be harmful".

An exception to the normal thinking regarding side-effects is Homeopathy. Since 1938, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has regulated homeopathic products in "several significantly different ways from other drugs."[129] Homeopathic preparations, termed "remedies," are extremely dilute, often far beyond the point where a single molecule of the original active (and possibly toxic) ingredient is likely to remain. They are, thus, considered safe on that count, but "their products are exempt from good manufacturing practice requirements related to expiration dating and from finished product testing for identity and strength," and their alcohol concentration may be much higher than allowed in conventional drugs.[129]

Treatment delay

Those having experienced or perceived success with one alternative therapy for a minor ailment may be convinced of its efficacy and persuaded to extrapolate that success to some other alternative therapy for a more serious, possibly life-threatening illness.[130] For this reason, critics argue that therapies that rely on the placebo effect to define success are very dangerous. According to mental health journalist Scott Lilienfeld in 2002, "unvalidated or scientifically unsupported mental health practices can lead individuals to forgo effective treatments" and refers to this as "opportunity cost". Individuals who spend large amounts of time and money on ineffective treatments may be left with precious little of either, and may forfeit the opportunity to obtain treatments that could be more helpful. In short, even innocuous treatments can indirectly produce negative outcomes.[28]

Between 2001 and 2003, four children died in Australia because their parents chose ineffective naturopathic, homeopathic, or other alternative medicines and diets rather than conventional therapies.[29] In all, they found 17 instances in which children were significantly harmed by a failure to use conventional medicine.

Unconventional cancer "cures"

Perhaps because many forms of cancer are difficult or impossible to cure, there have always been many therapies offered outside of conventional cancer treatment centers and based on theories not found in biomedicine. These alternative cancer cures have often been described as "unproven," suggesting that appropriate clinical trials have not been conducted and that the therapeutic value of the treatment is unknown. However, many alternative cancer treatments have been investigated in good-quality clinical trials, and they have been shown to be ineffective. [131]

Research funding

Although the Dutch government funded CAM research between 1986 and 2003, it formally ended funding in 2006.[132]

History

Fueled by a nationwide survey published in 1993 by David Eisenberg, which revealed that in 1990 approximately 60 million Americans had used one or more complementary or alternative therapies to address health issues.[133] A study published in the November 11, 1998 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that 42% of Americans had used complementary and alternative therapies, up from 34% in 1990.[134] However, despite the growth in patient demand for complementary medicine, most of the early alternative/complementary medical centers failed.[135]

Appeal

A study published in 1998[94] indicates that a majority of alternative medicine use was in conjunction with standard medical treatments. Approximately 4.4 percent of those studied used alternative medicine as a replacement for conventional medicine. The research found that those having used alternative medicine tended to have higher education or report poorer health status. Dissatisfaction with conventional medicine was not a meaningful factor in the choice, but rather the majority of alternative medicine users appear to be doing so largely because "they find these healthcare alternatives to be more congruent with their own values, beliefs, and philosophical orientations toward health and life." In particular, subjects reported a holistic orientation to health, a transformational experience that changed their worldview, identification with a number of groups committed to environmentalism, feminism, psychology, and/or spirituality and personal growth, or that they were suffering from a variety of common and minor ailments – notable ones being anxiety, back problems, and chronic pain.

Authors have speculated on the socio-cultural and psychological reasons for the appeal of alternative medicines among that minority using them in lieu of conventional medicine. There are several socio-cultural reasons for the interest in these treatments centered on the low level of scientific literacy among the public at large and a concomitant increase in antiscientific attitudes and new age mysticism.[136] Related to this are vigorous marketing[137] of extravagant claims by the alternative medical community combined with inadequate media scrutiny and attacks on critics.[138][136]

There is also an increase in conspiracy theories toward conventional medicine and pharmaceutical companies, mistrust of traditional authority figures, such as the physician, and a dislike of the current delivery methods of scientific biomedicine, all of which have led patients to seek out alternative medicine to treat a variety of ailments.[138] Many patients lack access to contemporary medicine, due to a lack of private or public health insurance, which leads them to seek out lower-cost alternative medicine.[92] Medical doctors are also aggressively marketing alternative medicine to profit from this market.[137]

In addition to the social-cultural underpinnings of the popularity of alternative medicine, there are several psychological issues that are critical to its growth. One of the most critical is the placebo effect, which is a well-established observation in medicine.[139] Related to it are similar psychological effects such as the will to believe,[136] cognitive biases that help maintain self-esteem and promote harmonious social functioning,[136] and the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy.[136]

Patients can also be averse to the painful, unpleasant, and sometimes-dangerous side effects of biomedical treatments. Treatments for severe diseases such as cancer and HIV infection have well-known, significant side-effects. Even low-risk medications such as antibiotics can have potential to cause life-threatening anaphylactic reactions in a very few individuals. Also, many medications may cause minor but bothersome symptoms such as cough or upset stomach. In all of these cases, patients may be seeking out alternative treatments to avoid the adverse effects of conventional treatments.[138][136]

Schofield et al., in a systematic review published in 2011, make ten recommendations which they think may increase the effectiveness of consultations in a conventional (here: oncology) setting, such as "Ask questions about CAM use at critical points in the illness trajectory"; "Respond to the person's emotional state"; and "Provide balanced, evidence-based advice". They suggest that this approach may address "... concerns surrounding CAM use [and] encourage informed decision-making about CAM and ultimately, improve outcomes for patients".[140]

CAM's popularity may be related to other factors which Edzard Ernst mentions in an interview in The Independent:

- Why is it so popular, then? Ernst blames the providers, customers and the doctors whose neglect, he says, has created the opening into which alternative therapists have stepped. "People are told lies. There are 40 million websites and 39.9 million tell lies, sometimes outrageous lies. They mislead cancer patients, who are encouraged not only to pay their last penny but to be treated with something that shortens their lives. "At the same time, people are gullible. It needs gullibility for the industry to succeed. It doesn't make me popular with the public, but it's the truth.[141]

In a paper published in October 2010 entitled The public's enthusiasm for complementary and alternative medicine amounts to a critique of mainstream medicine, Ernst describes these views in greater detail and concludes:

- [CAM] is popular. An analysis of the reasons why this is so points towards the therapeutic relationship as a key factor. Providers of CAM tend to build better therapeutic relationships than mainstream healthcare professionals. In turn, this implies that much of the popularity of CAM is a poignant criticism of the failure of mainstream healthcare. We should consider it seriously with a view of improving our service to patients.[142]

Physicians who practice complementary medicine usually discuss and advise patients as to available complementary therapies. Patients often express interest in mind-body complementary therapies because they offer a non-drug approach to treating some health conditions.[143] Some mind-body techniques, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, were once considered complementary medicine, but are now a part of conventional medicine in the United States.[144]

Efforts at abstract characterizations

There is no clear and consistent definition for either alternative or complementary medicine.[27]: 17

Self-characterization

The US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as "a group of diverse medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products, that are not currently part of conventional medicine”, in a context where conventional medicine is that which is scientifically proven.[19] This definition of CAM is widely known and used and is inclusive of many different types of therapies and products.[145][146]

The Danish Knowledge and Research Center for Alternative Medicine an independent institution under the Danish Ministry of the Interior and Health (Danish abbreviation: ViFAB) uses the term “alternative medicine” for:

- Treatments performed by therapists that are not authorized healthcare professionals, where authorized healthcare professionals are those practicing what is proven by science.

- Treatments performed by authorized healthcare professionals, but those based on methods otherwise used mainly outside the healthcare system, which is based on science in Denmark. People without a healthcare authorisation must be able to perform the treatments.

Institutions

The World Health Organization defines complementary and alternative medicine as a broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country's own tradition and are not integrated into the dominant health care system.[22]

In a consensus report released in 2005, entitled Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as the non-dominant approach to medicine in a given culture and historical period.[21] A similar definition has been adopted by the Cochrane Collaboration,[20][147] and official government bodies such as the UK Department of Health.[148] The Cochrane Collaboration Complementary Medicine Field definition is "complementary medicine includes all such practices and ideas that are outside the domain of conventional medicine in several countries and defined by its users as preventing or treating illness, or promoting health and well-being."[147] While some herbal therapies are mainstream in Europe, but are alternative in the United States.[149]

Medical education

Generally, Medical schools established in USA do not name alternative medicine as a teaching topic. Typically, their teaching is based on current practice and scientific knowledge about: anatomy, physiology, histology, embryology, neuroanatomy, pathology, pharmacology, microbiology and immunology.[150] Medical schools' teaching includes such topics as doctor-patient communication, ethics, the art of medicine,[151] and engaging in complex clinical reasoning (medical decision-making).[152] Medical schools are responsible for conferring medical degrees, but a physician typically may not legally practice medicine until licensed by the local government authority.

Special terminology used by selected individuals

According to Roberta Bivens, alternative medical systems can only exist when there is a identifiable, regularized and authoritative medical orthodoxy, such as arose in the west during the nineteenth-century, to which they can function or act as an alternative.[153] Two advocates of integrative medicine claim that it also addresses alleged problems with medicine based on science, which are not addressed by CAM; Ralph Snyderman and Andrew Weil state that "integrative medicine is not synonymous with complementary and alternative medicine. It has a far larger meaning and mission in that it calls for restoration of the focus of medicine on health and healing and emphasizes the centrality of the patient-physician relationship."[154]

Academic resources

- Cochrane and alternative medicine (full lists of updated reviews found on Knowledge and Research Center for Alternative Medicine)

See also

- Alternative cancer treatments

- Health freedom movement

- History of alternative medicine

- List of branches of alternative medicine

- Program for Evaluating Complementary Medicine

- Shakoor v Situ

- Traditional medicine

- Folk medicine

References

- ^ "White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy". March 2002. Archived from the original on 2011-08-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ernst E. (1995). "Complementary medicine: common misconceptions". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 88 (5): 244–247. PMC 1295191. PMID 7636814.

- ^ Joyce CR (1994). "Placebo and complementary medicine". The Lancet. 344 (8932): 1279–1281. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90757-9.

- ^ a b "Interview with [[Edzard Ernst]], editor of The Desktop Guide to Complementary and Alternative Medicine". Elsevier Science. 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ Cassileth BR, Deng G (2004). "Complementary and alternative therapies for cancer". The Oncologist. 9 (1): 80–9. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.9-1-80. PMID 14755017.

- ^ a b James May (12 July 2011). "College of Medicine: What is integrative health?". British Medical Journal. 343: d4372. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4372. PMID 21750063.

- ^ FDA, Drugs, information for consumers

- ^ NHS complementary provision

- ^ The Medical Journal of Australia: The Rise and Rise of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: a Sociological Perspective, Ian D Coulter and Evan M Willis, MJA, 2004; 180 (11): 587-589

- ^ BMJ (British Medical Journal) 'ABC of complementary medicine: What is complementary medicine?', Zollman, Catherine; Vickers, Andrew (11 September 1999), 'ABC of complementary medicine: What is complementary medicine?', British Medical Journal

- ^ Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (May 2012) [October 2008], CAM Basics: What is Complementary and Alternative Medicine, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

- ^ "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding Science Fiction and Pseudoscience - Belief in Alternative Medicine". National Science Foundation.

alternative medicine refers to all treatments that have not been proven effective using scientific methods

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Science Foundation survey: Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Public Understanding. Science Fiction and Pseudoscience.

- ^ a b c d e f g Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb23138.x , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb23138.xinstead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11242572, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 11242572instead. - ^ Other sources:

- Nature Medicine, September 1996, Volume 2 Number 9, p1042

- Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, Hines, Terence, American Psychological Association, [1]

- The Need for Educational Reform in Teaching about Alternative Therapies, Journal of the Association of Medical Colleges, March 2001 - Volume 76 - Issue 3 - p 248-250

- The Rise and Rise of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: a Sociological Perspective, Ian D Coulter and Evan M Willis, Medical Journal of Australia, 2004; 180 (11): 587-589

- Ignore Growing Patient Interest in Alternative Medicine at Your Peril - MDs Warned, Heather Kent, Canadian Medical Association Journal, November 15, 1997 vol. 157 no. 10

- The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, Carl Sagan, Random House, ISBN 0-394-53512-X, 1996

- ^ a b Ignore Growing Patient Interest in Alternative Medicine at Your Peril - MDs Warned, Heather Kent, Canadian Medical Association Journal, November 15, 1997 vol. 157 no. 10

- ^ a b c Goldrosen MH, Straus SE. "Complementary and alternative medicine: assessing the evidence for immunological benefits." Nature Perspectives, November 2004 vol. 4, pp. 912-921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "What is Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM)?". National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Archived from the original on 2005-12-08. Retrieved 2006-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Zollman C, Vickers A (1999). [/ "ABC of complementary medicine What is complementary medicine?"]. British Medical Journal. 319 (693): 693. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7211.693.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b "Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States". United States Institute of Medicine. 12 January 2005. pp. 16–20. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is a broad domain of resources that encompasses health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period. CAM includes such resources perceived by their users as associated with positive health outcomes. Boundaries within CAM and between the CAM domain and the domain of the dominant system are not always sharp or fixed.

- ^ a b "Traditional Medicine: Definitions". World Health Organization. 2000. Retrieved 2012-11-11.

- ^ Carroll RT. "complementary medicine" at The Skeptic's Dictionary

- ^ Acupuncture Pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine, Science Based Medicine, Steven Novella, Science-Based Medicine » Acupuncture Pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine

- ^ a b c Credulity about acupuncture infiltrates the New England Journal of Medicine, Science Based Medicine, David Gorski, Science-Based Medicine » Credulity about acupuncture infiltrates the New England Journal of Medicine

- ^ Acharya, Deepak and Shrivastava Anshu (2008). Indigenous Herbal Medicines: Tribal Formulations and Traditional Herbal Practices. Jaipur: Aavishkar Publishers Distributor. p. 440. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7.

- ^ a b c d e Institute of Med (2005). Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States. National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09270-8.

- ^ a b Lilienfeld, Scott O. (2002). "Our Raison d'Être". The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice. 1 (1). Archived from the original on 2007-07-26. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Dominic Hughes (23 December 2010). "Alternative remedies 'dangerous' for kids says report". BBC News.

- ^ "voluntary health agency focused upon health fraud, misinformation, and quackery as public health problems", notably Wallace Sampson and Paul Kurtz founders of Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine and Stephen Barrett, co-founder of The National Council Against Health Fraud[2] (NCAHF) and webmaster of Quackwatch

- ^ a b The Rise and Rise of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: a Sociological Perspective, Ian D Coulter and Evan M Willis, Medical Journal of Australia, 2004; 180 (11): 587-589

- ^ The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings, D. Wujastyk, p xviii, 2003, ISBN 0-14-044824-1

- ^ Underwood, E. Ashworth; Rhodes, P. (2008). "Medicine, History of". Encyclopædia Britannica (2008 ed.)

- ^ Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies, Lakshmi Chandra Mishra, CRC Press, 2004; ISBN 0-8493-1366-X, p. 8

- ^ Valiathan, M. S. (2006). "Ayurveda: Putting the House in Order". Current Science. 90 (1). Indian Academy of Sciences: 5–6.

- ^ Catherine A. Hammett-Stabler, Herbal Supplements: Efficacy, Toxicity, Interactions with Western Drugs, and Effects on Clinical Laboratory Tests (John Wiley and Sons, 2011; ISBN 0-470-43350-7), pp 202-205

- ^ CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Lead Poisoning Associated with Ayurvedic Medications — Five States, 2000–2003

- ^ Saper, R. B.; Phillips, R. S.; et al. (2008). "Lead, Mercury, and Arsenic in US- and Indian-manufactured ayurvedic Medicines Sold via the Internet". Journal of the American Medical Association. 300 (8): 915–923. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.915. PMC 2755247. PMID 18728265.

- ^ a b Beyerstein, BL (1996). "Traditional Medicine and Pseudoscience in China: A Report of the Second CSICOP Delegation (Part 1)". Skeptical Inquirer. 20 (4). Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Celestial lancets: a history and rationale of acupuncture and moxa, Needham, J; Lu GD, 2002, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1458-8

- ^ Tongue Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine, G Cia, 1995, Eastland Press. ISBN 0-939616-19-X.

- ^ Camillia Matuk (2006). "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration" (PDF). Journal of Biocommunication. 32 (1).

- ^ Medieval Transmission of Alchemical and Chemical Ideas Between China and India, Vijay Deshpande, Indiana Journal of History of Science, 22 (1), pp. 15-28, 1987

- ^ Crozier RC (1968). Traditional medicine in modern China: science, nationalism, and the tensions of cultural change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Taylor, K (2005). Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945–63: a Medicine of Revolution. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-415-34512-X.

- ^ Hahnemann, Samuel (1833). The Homœopathic Medical Doctrine, or "Organon of the Healing Art". Translated by Charles H. Devrient, Esq. Dublin: W.F. Wakeman. pp. iii, 48–49.

Observation, reflection, and experience have unfolded to me that the best and true method of cure is founded on the principle, similia similibus curentur. To cure in a mild, prompt, safe, and durable manner, it is necessary to choose in each case a medicine that will excite an affection similar (ὅμοιος πάθος) to that against which it is employed.

- ^ Ernst, E. (2002), "A systematic review of systematic reviews of homeopathy", British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54 (6): 577–82, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01699.x, PMC 1874503, PMID 12492603

- ^ UK Parliamentary Committee Science and Technology Committee - "Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy"

- ^ Shang, Aijing; Huwiler-Müntener, Karin; Nartey, Linda; Jüni, Peter; Dörig, Stephan; Sterne, Jonathan AC; Pewsner, Daniel; Egger, Matthias (2005), "Are the clinical effects of homoeopathy placebo effects? Comparative study of placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy and allopathy", The Lancet, 366 (9487): 726–732, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67177-2, PMID 16125589

- ^ http://nccam.nih.gov/health/homeopathy "Homeopathy: An Introduction" a NCCAM webpage

- ^ Wahlberg, A (2007), "A quackery with a difference—New medical pluralism and the problem of 'dangerous practitioners' in the United Kingdom", Social Science & Medicine, 65 (11): 2307–16, doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.024, PMID 17719708

- ^ Sarris, J., and Wardle, J. 2010. Clinical naturopathy: an evidence-based guide to practice. Elsevier Australia. Chatswood, NSW.

- ^ Jagtenberg T., Evans S., Grant A., Howden I., Lewis M., Singer J. (2006). "Evidence-based medicine and naturopathy". J Altern Complement Med. 12 (3): 323–8. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.12.323. PMID 16646733.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ernst E (2001). "Rise in popularity of complementary and alternative medicine: reasons and consequences for vaccination". Vaccine. 20 (Suppl 1): S89–93. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00290-0. PMID 11587822.

- ^

"Naturopathic Medicine". American Cancer Society. 01 Nov 08. Retrieved 20 Nov 10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Demon Haunted World, Carl Sagan

- ^ Psychophysiologic Effects of Hatha Yoga on Musculoskeletal and Cardiopulmonary Function: A Literature Review, The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, J. A. Raub, (2002), 8(6): 797-812. doi:10.1089/10755530260511810.

- ^ a b According to a New Government Survey, 38 Percent of Adults and 12 Percent of Children Use Complementary and Alternative Medicine, NIH, [3]

- ^ Sampson, Wallace (1 June 1995). "Antiscience trends in the rise of the "alternative medicine" movement". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 775 (1): 189–191. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb23138.x. Wallace Sampson

- ^ a b "Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Cancer Treatment". National Vancer Institute. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|deadurl=(help) - ^ a b Borkan, Jeffrey (2012). "Complementary alternative health care in Israel and the western world". Isr J Health Policy Res. 1 (8). doi:10.1186/2045-4015-1-8. PMID 22913745.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kong SC, Hurlstone DP, Pocock CY, Walkington LA, Farquharson NR, Bramble MG, McAlindon ME, Sanders DS. (2005). "The Incidence of self-prescribed oral complementary and alternative medicine use by patients with gastrointestinal diseases". J Clin Gastroenterol. 39 (2): 138–41. PMID 15681910.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stuber, Margaret (2012). "Complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine". In Cobb, Puchalski, and Rumbold (ed.). Oxford Textbook of Spirituality in Healthcare. Oxford: Oxford Univ press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-957139-0.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "What is CAM?". NCCAM. 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ a b Angell M, Kassirer JP (1998). "Alternative medicine--the risks of untested and unregulated remedies" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (12): 839–41. doi:10.1056/NEJM199809173391210. PMID 9738094.

It is time for the scientific community to stop giving alternative medicine a free ride. There cannot be two kinds of medicine – conventional and alternative. There is only medicine that has been adequately tested and medicine that has not, medicine that works and medicine that may or may not work. Once a treatment has been tested rigorously, it no longer matters whether it was considered alternative at the outset. If it is found to be reasonably safe and effective, it will be accepted. But assertions, speculation, and testimonials do not substitute for evidence. Alternative treatments should be subjected to scientific testing no less rigorous than that required for conventional treatments.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The New England Journal of Medicine, July 1995.

- ^ a b Scientists Speak Out Against Federal Funds for Research on Alternative Medicine – washingtonpost.com

- ^ Fontanarosa PB, Lundberg GD (1998). "Alternative medicine meets science". JAMA. 280 (18): 1618–9. doi:10.1001/jama.280.18.1618. PMID 9820267.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Leader: Virtually all alternative medicine is bunk, but the placebo effect is rather interesting". The Economist. 19 May 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ^ a b Sampson W, Atwood Iv K (2005). "Propagation of the absurd: demarcation of the absurd revisited". Med. J. Aust. 183 (11–12): 580–1. PMID 16336135.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2003). A Devil's Chaplain. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-618-33540-4.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Dawkins, Richard (2003). A Devil's Chaplain. United States: Houghton Mifflin. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-618-33540-4.

- ^ "Review: A Devil's Chaplain by Richard Dawkins". The Guardian. London. 2003-02-15. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cassileth BR (1999). "Evaluating complementary and alternative therapies for cancer patients". CA Cancer J Clin. 49 (6): 362–75. doi:10.3322/canjclin.49.6.362. PMID 11198952.

- ^ a b c Brown, David (March 17, 2009). "Scientists Speak Out Against Federal Funds for Research on Alternative Medicine". Washingtonpost. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ a b c "Cochrane CAM Field: Integrative Medicine".

- ^ a b Barrett, Stephen (February 10, 2004). "Be Wary of "Alternative" Health Methods". Stephen Barrett, M.D. Quackwatch. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ a b c "Complementary medicine: the good the bad and the ugly". Edzard Ernst.

- ^ The Economist, "Alternative Medicine: Think yourself better", 21 May 2011, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c "$2.5 billion spent, no alternative cures found – Alternative medicine- msnbc.com". MSNBC. June 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Why the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) Should Be Defunded

- ^ Research Results of Complementary and Alternative Medicine [NCCAM Research]

- ^ Acupuncture Pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine, Science Based Medicine, Steven Novella Science-Based Medicine » Acupuncture Pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine

- ^ Edzard Ernst. "Alternative medicine remains an ethics-free zone." The Guardian 8 November 2011

- ^ a b Mark Henderson, Science Editor, "Prince of Wales's guide to alternative medicine 'inaccurate'" Times Online, April 17, 2008

- ^ a b "Complementary medicine is diagnosis, treatment and/or prevention that complements mainstream medicine by contributing to a common whole, by satisfying a demand not met by orthodoxy or by diversifying the conceptual frameworks of medicine." Ernst et al. British General Practitioner 1995; 45:506.

- ^ Butler K (1992). A Consumer's Guide to "ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE": A close look at Homeopathy, Acupuncture, Faith-healing and other Unconventional Treatments

- ^ "real acupuncture treatments were no more effective than sham acupuncture treatments. There was, nevertheless, evidence that both real acupuncture and sham acupuncture were more effective than no treatment, and that acupuncture can be a useful supplement to other forms of conventional therapy for low back pain", Acupuncture for Chronic Low Back Pain, New England Journal of Medicine, 2010; 363:454-461, Brian M. Berman, M.D., Brian M. Berman, founder of the Center for Integrative Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Helene M. Langevin, M.D., Claudia M. Witt, M.D., M.B.A., and Ronald Dubner, D.D.S., Ph.D., MMS: Error Template:WebCite

- ^ Kermen R, Hickner J, Brody H, Hasham I (2010). "Family physicians believe the placebo effect is therapeutic but often use real drugs as placebos". Fam Med. 42 (9): 636–42. PMID 20927672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.stfm.org/fmhub/fm2010/October/Rachel636.pdf

- ^ Ernst E (2003). "Obstacles to research in complementary and alternative medicine". The Medical Journal of Australia. 179 (6): 279–80. PMID 12964907.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL (2004). "Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002" (PDF). Advance Data (343): 1–19. PMID 15188733.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reasons people use CAM. NCCAM

- ^ a b Astin JA (1998). "Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study". JAMA. 279 (19): 1548–53. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. PMID 9605899.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. (2011). "How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis". Integr Cancer Ther. 11 (3): 187–203. doi:10.1177/1534735411423920. PMID 22019489.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Eisenberg DM; Davis RB; Ettner SL; et al. (1998). "Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey". JAMA. 280 (18): 1569–75. doi:10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. PMID 9820257.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ House of Lords report on CAM Template:WebCite

- ^ a b c "Trends in Alternative Medicine Use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a Follow-up National Survey." Journal of the American Medical Association, Eisenberg, D.M., R.B. Davis, S.I. Ettner, et al, 280: 1569–75, 1998

- ^ Alternative Medicine Goes Mainstream CBS News. Published July 20, 2006. Retrieved June 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "Press Release : Latest Survey Shows More Hospitals Offering Complementary and Alternative Medicine Services". American Hospital Association. 2008-09-15. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ "A Close Look at Therapeutic Touch." Journal of the American Medical Association, Rosa, L., Rosa, E., Sarner, L., and Barrett, S. 279(13): 1005–10, 1998

- ^ Cassileth, Barrie R. (June 1996). "Alternative and Complementary Cancer Treatments". The Oncologist. 1 (3): 173–9. PMID 10387984.

- ^ Marty (1999). "The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines". J Amer Med Assoc. 281 (19): 1852–3. doi:10.1001/jama.281.19.1852.

- ^ "Traditional medicine". Fact sheet 134. World Health Organization. 2003-05. Archived from the original on 2008-07-28. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas KJ, Nicholl JP, Coleman P (2001). "Use and expenditure on complementary medicine in England: a population based survey". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 9 (1): 2–11. doi:10.1054/ctim.2000.0407. PMID 11264963.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://nccam.nih.gov/sites/nccam.nih.gov/files/news/nhsr12.pdf/

- ^ House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology. 2000. Complementary and Alternative Medicine. London: The Stationery Office.

- ^ NHS complementary provision

- ^ Glossary, Continuum Health Partners, 2005.

- ^ Allan Kellehear, Complementary medicine: is it more acceptable in palliative care practice? MJA 2003; 179 (6 Suppl): S46-S48 online

- ^ Menefee LA, Monti DA (2005). "Nonpharmacologic and complementary approaches to cancer pain management". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 105 (suppl 5): S15–20. PMID 16368903.