Didache

The Didache (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈdɪdəkiː/; Koine Greek: Διδαχή) or The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (Didachē means "Teaching"[1]) is a brief early Christian treatise, dated by most scholars to the late first or early 2nd century.[2] But J.A.T. Robinson argues that it is first generation, dating it c. A.D.40-60.[3] The first line of this treatise is "Teaching of the Lord to the Gentiles (or Nations) by the Twelve Apostles"[4]

The text, parts of which constitute the oldest surviving written catechism, has three main sections dealing with Christian ethics, rituals such as baptism and Eucharist, and Church organization. It is considered the first example of the genre of the Church Orders.

The work was considered by some of the Church Fathers as part of the New Testament[5] but rejected as spurious or non-canonical by others,[6] eventually not accepted into the New Testament canon. The Ethiopian Orthodox Church "broader canon" includes the Didascalia, a work which draws on the Didache.

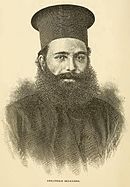

Lost for centuries, a Greek manuscript of the Didache was rediscovered in 1873 by Philotheos Bryennios, Metropolitan of Nicomedia in the Codex Hierosolymitanus. A Latin version of the first five chapters was discovered in 1900 by J. Schlecht.[7] The Didache is considered part of the category of second-generation Christian writings known as the Apostolic Fathers.

Date, composition and modern translation

Most scholars place the Didache at some point during the mid to late first century.[8] It is an anonymous work, a pastoral manual "that reveals more about how Jewish-Christians saw themselves and how they adapted their Judaism for gentiles than any other book in the Christian Scriptures."[9]

Hitchcock and Brown produced the first English translation in March 1884. Harnack produced the first German translation in 1884, and Sabatier the first translation and commentary in 1885.[10]

Early references

The Didache is mentioned by Eusebius (c. 324) as the Teachings of the Apostles following the books recognized as canonical:[11]

- "Let there be placed among the spurious works the Acts of Paul, the so-called Shepherd and the Apocalypse of Peter, and besides these the Epistle of Barnabas, and what are called the Teachings of the Apostles, and also the Apocalypse of John, if this be thought proper; for as I wrote before, some reject it, and others place it in the canon."

Athanasius (367) and Rufinus (c. 380) list the Didache among apocrypha. (Rufinus gives the curious alternative title Judicium Petri, "Judgment of Peter".) It is rejected by Nicephorus (c. 810), Pseudo-Anastasius, and Pseudo-Athanasius in Synopsis and the 60 Books canon. It is accepted by the Apostolic Constitutions Canon 85, John of Damascus and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The Adversus Aleatores by an imitator of Cyprian quotes it by name. Unacknowledged citations are very common, if less certain. The section Two Ways shares the same language with the Epistle of Barnabas, chapters 18-20, sometimes word for word, sometimes added to, dislocated, or abridged, and Barnabas iv, 9 either derives from Didache, 16, 2-3, or vice versa. There can also be seen many similarities to the Epistles of both Polycarp and Ignatius of Antioch.The Shepherd of Hermas seems to reflect it, and Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria,[12] and Origen of Alexandria also seem to use the work, and so in the West do Optatus and the Gesta apud Zenophilum. The Didascalia Apostolorum are founded upon the Didache. The Apostolic Church-Ordinances has used a part, the Apostolic Constitutions have embodied the Didascalia. There are echoes in Justin Martyr, Tatian, Theophilus of Antioch, Cyprian, and Lactantius.

Contents

The contents may be divided into four parts, which most scholars agree were combined from separate sources by a later redactor: the first is the Two Ways, the Way of Life and the Way of Death (chapters 1-6); the second part is a ritual dealing with baptism, fasting, and Communion (chapters 7-10); the third speaks of the ministry and how to deal with traveling prophets (chapters 11-15); and the final section (chapter 16) is a brief apocalypse.[citation needed]

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish Christianity |

|---|

|

Title

The manuscript is commonly referred to as the Didache. This is short for the header found on the document and the title used by the Church Fathers, "The Lord's Teaching of the Twelve Apostles"[13] which Jerome said was the same as the Gospel according to the Hebrews. A fuller title or subtitle is also found next in the manuscript, "The Teaching of the Lord to the Gentiles[14] by the Twelve Apostles".[15]

Description

Willy Rordorf considered the first five chapters as "essentially Jewish, but the Christian community was able to use it" by adding the "evangelical section".[16] "Lord" in the Didache is reserved usually for "Lord God", while Jesus is called "the servant" of the Father (9:2f.; 10:2f.).[17] Baptism was practised "in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit."[18] Scholars generally agree that 9:5, which speaks of baptism "in the name of the Lord," represents an earlier tradition that was gradually replaced by a trinity of names."[17][19] A similarity with Acts 3 is noted by Aaron Milavec: both see Jesus as "the servant (pais)[20] of God".[21] The community is presented as "awaiting the kingdom from the Father as entirely a future event".[21]

The Two Ways

The first section (Chapters 1-6) begins: "There are two ways, one of life and one of death, and there is a great difference between these two ways."[22]

In Apostolic Fathers, 2nd ed., Lightfoot-Harmer-Holmes, 1992, notes:

- The Two Ways material appears to have been intended, in light of 7.1, as a summary of basic instruction about the Christian life to be taught to those who were preparing for baptism and church membership. In its present form it represents the Christianization of a common Jewish form of moral instruction. Similar material is found in a number of other Christian writings from the first through about the fifth centuries, including the Epistle of Barnabas, the Didascalia, the Apostolic Church Ordinances, the Summary of Doctrine, the Apostolic Constitutions, the Life of Schnudi, and On the Teaching of the Apostles (or Doctrina), some of which are dependent on the Didache. The interrelationships between these various documents, however, are quite complex and much remains to be worked out.

The closest parallels in the use of the Two Ways doctrine is found among the Essene Jews at the Dead Sea Scrolls community. The Qumran community included a Two Ways teaching in its founding Charter, The Community Rule.

Throughout the Two Ways, there are many Old Testament quotes shared with the Gospels and many theological similarities, but Jesus is never mentioned by name. The first chapter opens with the Shema ("you shall love God"), the Great Commandment ("your neighbor as yourself"), and the Golden Rule in the negative form (also found in the "Western" version of Acts of the Apostles at 15:19 and 29 as part of the Apostolic Decree). Then comes short extracts in common with the Sermon on the Mount, together with a curious passage on giving and receiving, which is also cited with variations in Shepherd of Hermas (Mand., ii, 4-6). The Latin omits 1:3-6 and 2:1, and these sections have no parallel in Epistle of Barnabas; therefore, they may be a later addition, suggesting Hermas and the present text of the Didache may have used a common source, or one may have relied on the other. Chapter 2 contains the commandments against murder, adultery, corrupting boys, sexual promiscuity, theft, magic, sorcery, abortion, infanticide, coveting, perjury, false testimony, speaking evil, holding grudges, being double-minded, not acting as you speak, greed, avarice, hypocrisy, maliciousness, arrogance, plotting evil against neighbors, hate, narcissism and expansions on these generally, with references to the words of Jesus. Chapter 3 attempts to explain how one vice leads to another: anger to murder, concupiscence to adultery, and so forth. The whole chapter is excluded in Barnabas. A number of precepts are added in chapter 4, which ends: "This is the Way of Life." Verse 13 states you must not forsake the Lord's commandments, neither adding nor subtracting (see also Deut 4:2,12:32). The Way of Death (chapter 5) is a list of vices to be avoided. Chapter 6 exhorts to the keeping in the Way of this Teaching:

- See that no one causes you to err from this way of the teaching, since apart from God it teaches you. For if you are able to bear the entire yoke of the Lord, you will be perfect; but if you are not able to do this, do what you are able. And concerning food, bear what you are able; but against that which is sacrificed to idols be exceedingly careful; for it is the service of dead gods. (Roberts)

The Didache, like 1 Corinthians 10:21, does not give an absolute prohibition on eating meat which has been offered to idols, but merely advises to be careful.[23] Comparable to the Didache is the "let him eat herbs" of Paul of Tarsus as a hyperbolical expression like 1 Cor 8:13: "I will never eat flesh, lest I should scandalize my brother", thus giving no support to the notion of vegetarianism in the Early Church. John Chapman in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) states that the Didache is referring to Jewish meats.[7] The Latin version substitutes for chapter 6 a similar close, omitting all reference to meats and to idolothyta, and concluding with per Domini nostri Jesu Christi ... in saecula saeculorum, amen, "by our lord Jesus Christ ... for ever and ever, amen". This is the end of the translation. This suggests the translator lived at a day when idolatry had disappeared, and when the remainder of the Didache was out of date. He had no such reason for omitting chapter 1, 3-6, so that this was presumably not in his copy.[7]

Rituals

Baptism

The second part (chapters 7 to 10) begins with an instruction on baptism, which is to be conferred "in the Name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit"[18] in “living water” (that is, natural flowing water), if it can be had — if not, in cold or even warm water. The baptized and the baptizer, and, if possible, anyone else attending the ritual should fast for one or two days beforehand. If the water is insufficient for immersion, it may be poured three times on the head. A century ago, this point was used by Dr. C. Bigg[24][25][26] to demonstrate the document's late date, a position no longer current among scholars.[citation needed]

Fasting

Chapter 8 suggests that fasts are not to be on Monday and Thursday "with the hypocrites" — presumably non-Christian Jews — but on Wednesday and Friday. Nor must Christians pray with their Judaic brethren, instead they shall say the Lord's Prayer three times a day. The text of the prayer is not identical to the version in the Gospel of Matthew, and it is given with the doxology "for Thine is the power and the glory for ever." The Didache is the main source for the inclusion of the doxology. It does not occur within the oldest copies of the texts of Matthew and Luke. Most biblical scholars agree that it was included as a result of a later edit.[citation needed]

Eucharist

Chapter 9 concerns the Eucharist ("thanksgiving"):

- "Now concerning the Eucharist, give thanks this way. First, concerning the cup:

- We thank thee, our Father, for the holy vine of David Thy servant, which Thou madest known to us through Jesus Thy Servant; to Thee be the glory for ever..

And concerning the broken bread:

- We thank Thee, our Father, for the life and knowledge which Thou madest known to us through Jesus Thy Servant; to Thee be the glory for ever. Even as this broken bread was scattered over the hills, and was gathered together and became one, so let Thy Church be gathered together from the ends of the earth into Thy kingdom; for Thine is the glory and the power through Jesus Christ for ever..

- But let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist, unless they have been baptized into the name of the Lord; for concerning this also the Lord has said, "Give not that which is holy to the dogs." (Roberts)

The Didache basically describes the same ritual as the one that took place in Corinth.[27] The order of cup and bread differs both from present-day Christian practice and from that in the New Testament accounts of the Last Supper,[28] of which, again unlike almost all present-day Eucharistic celebrations, the Didache makes no mention.

Chapter 10 gives a thanksgiving after a meal. The contents of the meal are not indicated: chapter 9 does not exclude other elements as well that the cup and bread, which are the only ones it mentions, and chapter 10, whether it was originally a separate document or continues immediately the account in chapter 9, mentions no particular elements, not even wine and bread. Instead it speaks of the "spiritual food and drink and life eternal through Thy Servant" that it distinguishes from the "food and drink (given) to men for enjoyment that they might give thanks to (God)". After a doxology, as before, come the apocalyptic exclamations: "Let grace come, and let this world pass away. Hosanna to the God (Son) of David! If any one is holy, let him come; if any one is not so, let him repent. Maranatha. Amen". The prayer is reminiscent of Revelation 22:17–20 and 1Corinthians 16:22.[29]

These prayers make no reference to the redemptive death of Christ, or remembrance, as formulated by Paul the Apostle in 1Corinthians 11:23–34, see also Substitutionary atonement. Didache 10 doesn't even use the word "Christ," which appears only one other time in the whole tract.

Some have posited that, in spite of the order in the manuscript text, chapter 10 should precede chapter 9: "Some scholars rearranged the text of chapters 9 & 10 (in comparison with chapter 14) to accommodate their view that the later Roman Mass is closer to what they understand to be truly Christian" (Wim van den Dungen). John Dominic Crossan endorses John W. Riggs' 1984 The Second Century article for the proposition that 'there are two quite separate eucharistic celebrations given in Didache 9-10, with the earlier one now put in second place."[30] The section beginning at 10.1 is a reworking of the Jewish birkat ha-mazon, a three-strophe prayer at the conclusion of a meal, which includes a blessing of God for sustaining the universe, a blessing of God who gives the gifts of food, earth, and covenant, and a prayer for the restoration of Jerusalem; the content is "Christianized", but the form remains Jewish.[31] It is similar to the Syrian Church eucharist rite of the Holy Qurbana of Addai and Mari, belonging to "a primordial era when the euchology of the Church had not yet inserted the Institution Narrative in the text of the Eucharistic Prayer."[32]

Resurrection

The Didache makes no mention of Jesus' resurrection, other than thanking for "immortality, which Thou hast made known unto us through Thy Son Jesus" in the eucharist,[33] but the Didache makes specific reference to the resurrection of the just prior to the Lord's coming.[34]

Matthew and the Didache

Some have stated[35] that the Didache can be dated to about the turn of the 2nd century. At the same time, significant similarities between the Didache and the gospel of Matthew have been found[36] as these writings share words, phrases, and motifs. There is also an increasing reluctance of modern scholars to support the thesis that the Didache used Matthew. This close relationship between these two writings might suggest that both documents were created in the same historical and geographical setting. One argument that suggests a common environment is that the community of both the Didache and the gospel of Matthew was probably composed of Jewish Christians from the beginning.[36] Also, the Two Ways teaching (Did. 1-6) may have served as a pre-baptismal instruction within the community of the Didache and Matthew. Furthermore, the correspondence of the Trinitarian baptismal formula in the Didache and Matthew (Did. 7 and Matt 28:19) as well as the similar shape of the Lord's Prayer (Did. 8 and Matt 6:5-13) appear to reflect the use of similar oral traditions. Finally, both the community of the Didache (Did. 11-13) and Matthew (Matt 7:15-23; 10:5-15, 40-42; 24:11,24) were visited by itinerant apostles and prophets, some of whom were illegitimate.[36]

See also

- Ancient Church Orders

- Brotherly love (philosophy)

- Codex Hierosolymitanus

- Gospel according to the Hebrews

Footnotes

- ^ Strong's G1322 Didache: instruction (the act or the matter): - doctrine, hath been taught.

- ^ Draper, J. A. (2006). "The Apostolic Fathers: The Didache". The Expository Times. 117 (5): 177–81. doi:10.1177/0014524606062770.

- ^ John A. T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (SCM Press 1976)

- ^ Greek: Διδαχὴ κυρίου διὰ τῶν δώδεκα ἀποστόλων τοῖς ἔθνεσιν

- ^ Rufinus, Commentary on Apostles Creed 37 (as Deuterocanonical) c. 380; John of Damascus Exact Exposition of Orthodox Faith 4.17; and the 81-book canon of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church

- ^ Athanasius, Festal Letter 39 (excludes them from the canon, but recommends them for reading) in 367; Rejected by 60 Books Canon and by Nicephorus in Stichometria

- ^ a b c John Chapman (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3): Didache

- ^ Aaron Milavec, The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian communities, 50-70 C.E., p. vii

- ^ Aaron Milavec in The Didache in context: essays on its text, history, and transmission ed. Clayton N. Jefford p140-141.

- ^ Historia Ecclesiastica III, 25.

- ^ Clement quotes the Didache as scripture. Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

- ^ Greek: Διδαχὴ Κυρίου διὰ τῶν δώδεκα ἀποστόλων, Didachē Kiriou dia tōn dōdeka apostolōn

- ^ Some translations "Nations", see Strong's 1484

- ^ Greek: Διδαχὴ κυρίου διὰ τῶν δώδεκα ἀποστόλων τοῖς ἔθνεσιν, Didachē kyriou dia tōn dōdeka apostolōn tois ethnesin

- ^ Aaron Milavec, The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian communities, 50-70 C.E., p. 110

- ^ a b Aaron Milavec, The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian communities, 50-70 C.E., p. 271

- ^ a b The Didache or Teaching of the Apostles, trans. and ed., J. B. Lightfoot, 7:2,5

- ^ In the cited reference (Aaron Milavec, p. 271), the Didache verse ("But let no one eat or drink of this eucharistic thanksgiving, but they that have been baptized into the name of the Lord", The Didache or Teaching of the Apostles, trans. and ed., J. B. Lightfoot, 9:10) is erroneously indicated as 9:5

- ^ Acts 3:13 describes Jesus as παῖς: "a boy (as often beaten with impunity), or (by analogy) a girl, and (generally) a child; specifically a slave or servant (especially a minister to a king; and by eminence to God): - child, maid (-en), (man) servant, son, young man" Strong's G3817

- ^ a b Aaron Milavec, The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian communities, 50-70 C.E., p. 368

- ^ Holmes, Apostolic Fathers

- ^ Aaron Milavec The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian 2003 p252 citing Wendell Willis "It is interesting, nonetheless, that both Paul and the Didache take a flexible approach save when it comes to eating food sacrificed to idols. Paul makes use of the phrase "table of demons" ( 1 Cor 10:21)."

- ^ Bigg, C. (1904). "Notes on the Didache. I: On Baptism by Affusion". The Journal of Theological Studies (20): 579–84. doi:10.1093/jts/os-V.20.579.

- ^ Bigg, C. (1904). "Notes on the Didache. II: On Certain Points in the First Chapter". The Journal of Theological Studies (20): 584–9. doi:10.1093/jts/os-V.20.584.

- ^ Bigg, C. (1905). "Notes on the Didache". The Journal of Theological Studies (23): 411–5. doi:10.1093/jts/os-VI.23.411.

- ^ Valeriy A. Alikin The earliest history of the Christian gathering Brill 2010 ISBN 978-90-04-18309-4 p110 "...practice of a particular community or group of communities.29 However, the Didache basically describes the same ritual as the one that took place in Corinth. This is probable for several reasons. In both cases, the meal was a community supper that took place on Sunday evening where the participants could eat their fill, rather than purely a symbolic ritual.30 Also in both cases the meal began with separate benedictions over the bread and wine (Mark 14:22-25 par.).."

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:23–25, Mark 14:22–25, Matthew 26:26–29, Luke 22:14–20

- ^ Rev. 22:17-20 reads, "The Spirit and the Bride say, 'Come,' And let the one who hears say, 'Come.' And let the one who is thirsty come; let the one who desires take the water of life without price. / I warn everyone who hears the words of the prophecy of this book: if anyone adds to them, God will add to him the plagues described in this book, and if anyone takes away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God will take away his share in the tree of life and in the holy city, which are described in this book. / He who testifies to these things says, 'Surely I am coming soon.' Amen. Come, Lord Jesus!" (English Standard Version). I Cor. 16:22 reads, "If anyone has no love for the Lord, let him be accursed. Our Lord, come! [Greek Maranatha]" (ESV).

- ^ Crossan, The Historical Jesus, p 361 (1991)

- ^ The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and Its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity by Hubertus Waltherus Maria van de Sandt, David Flusser pp 311-2; Metaphors of Sacrifice in the Liturgies of the Early Church by Stephanie Perdew; Jüdische Wurzel by Franz D. Hubmann

- ^ Sarhad Yawsip Jammo, The Anaphora of Addai and Mari: A Study of Structure and Historical Background

- ^ Wade, Nicholas. The Faith Instinct: How Religion Evolved and Why It Endures. Penguin Press HC. 2009. ISBN 1-59420-228-1

- ^ The Didache in context: essays on its text, history, and transmission p151 N. Jefford - 1995 "According to the end-time scenario of the Didache, the destruction of the lawless, the purification of the faithful, and the selective resurrection of the just occur prior to the Lord's coming"

- ^ Lee Martin McDonald, The Biblical Canon: Its Origin, Transmission, and Authority, Henrickson Publishers, 2007, p. 261 n. 54; ISBN 978-1-56563-925-6

- ^ a b c H. van de Sandt (ed), Matthew and the Didache, (Assen: Royal van Gorcum; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 2005).

References

- Van de Sandt, H.W.M (2005). Matthew and the Didache: two documents from the same Jewish-Christian milieu?. Royal Van Gorcum/Fortress. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.

- Jefford, Clayton N (1995). The Didache in context: essays on its text, history, and transmission. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10045-9.

- Draper, Jonathan A (1996). The Didache in modern research:an overview. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10375-7.

- Slee, Michelle (2003). The church in Antioch in the first century CE: communion and conflict. Sheffield Academic. ISBN 978-0-567-08382-1.

- Milavec, Aaron (2003). The Didache: text, translation, analysis, and commentary. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5831-4.

- Milavec, Aaron (2003). The Didache: faith, hope, & life of the earliest Christian communities, 50-70 CE. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-0537-3.

- Del Verme, Marcello (2004). Didache and Judaism: Jewish roots of an ancient Christian-Jewish work. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-02531-9.

- Jefford, Clayton N (1989). The sayings of Jesus in the Teaching of the Twelve Apostles. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09127-6.

- Audet, Jean-Paul, La Didache, Instructions des Apôtres, J. Gabalda & Co., 1958.

- Draper, J. A. (2006). "The Apostolic Fathers: The Didache". The Expository Times. 117 (5): 177–81. doi:10.1177/0014524606062770.

- Holmes, Michael W., ed., The Apostolic Fathers: Greek Texts and English Translations, Baker Academic, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8010-3468-8

- Jones, Tony, The Teaching of the Twelve: Believing & Practicing the Primitive Christianity of the Ancient Didache Community, Paraclete Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-55725-590-7

- Lightfoot, Joseph Barber, et al., Apostolic Fathers, London: Macmillan and Co. 1889.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Greek text in Latin alphabet from Universität Bremen

- Didache text in Greek from CCEL

- Many English translations of the Didache

- Didache translated by Philip Schaff

- Didache translated by Richardson, Cyril C.

- Didache translated by Charles H. Hoole. - English translation hosted by about.com

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Didache, article from the 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Annotated Bibliography of the Didache

- earlychurch.org.uk The Didache: Its Origin And Significance

- upenn.edu Electronic Edition by Robert A. Kraft (updated 28 July 1995)

- 2012 Translation & Audio Version