Breast

| Breast | |

|---|---|

The breasts of a pregnant woman | |

| Details | |

| Artery | internal thoracic artery |

| Vein | internal thoracic vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | mamma (mammalis "of the breast")[1] |

| MeSH | D001940 |

| TA98 | A16.0.02.001 |

| TA2 | 7097 |

| FMA | 9601 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The breast is the upper ventral region of the torso of a primate, in left and right sides, containing the mammary gland which in a female can secrete milk used to feed infants.

Both men and women develop breasts from the same embryological tissues. However, at puberty, female sex hormones, mainly estrogen, promote breast development which does not occur in men due to the higher amount of testosterone. As a result, women's breasts become far more prominent than those of men.

During pregnancy, the breast is responsive to a complex interplay of hormones that cause tissue development and enlargement in order to produce milk. Three such hormones are estrogen, progesterone and prolactin, which cause glandular tissue in the breast and the uterus to change during the menstrual cycle.[2]

Each breast contains 15–20 lobes. The subcutaneous adipose tissue covering the lobes gives the breast its size and shape. Each lobe is composed of many lobules, at the end of which are sacs where milk is produced in response to hormonal signals.[2]

Etymology

The English word breast derives from the Old English word brēost (breast, bosom) from Proto-Germanic breustam (breast), from the Proto-Indo-European base bhreus– (to swell, to sprout).[3] The breast spelling conforms to the Scottish and North English dialectal pronunciations.[4]

Structure

1. Chest wall

2. Pectoralis muscles

3. Lobules

4. Nipple

5. Areola

6. Milk duct

7. Fatty tissue

8. Skin

In women, the breasts overlay the pectoralis major muscles and usually extend from the level of the second rib to the level of the sixth rib in the front of the human rib cage; thus, the breasts cover much of the chest area and the chest walls. At the front of the chest, the breast tissue can extend from the clavicle (collarbone) to the middle of the sternum (breastbone). At the sides of the chest, the breast tissue can extend into the axilla (armpit), and can reach as far to the back as the latissimus dorsi muscle, extending from the lower back to the humerus bone (the longest bone of the upper arm). As a mammary gland, the breast is an composed of layers of different types of tissue, among which predominate two types, adipose tissue and glandular tissue, which effects the lactation functions of the breasts. [5]: 115

Morphologically, the breast is a cone with the base at the chest wall, and the apex at the nipple, the center of the NAC (nipple-areola complex). The superficial tissue layer (superficial fascia) is separated from the skin by 0.5–2.5 cm of subcutaneous fat (adipose tissue). The suspensory Cooper's ligaments are fibrous-tissue prolongations that radiate from the superficial fascia to the skin envelope. The adult breast contains 14–18 irregular lactiferous lobes that converge to the nipple, to ducts 2.0–4.5 mm in diameter; the milk ducts (lactiferous ducts) are immediately surrounded with dense connective tissue that functions as a support framework. The glandular tissue of the breast is biochemically supported with estrogen; thus, when a woman reaches menopause (cessation of menstruation) and her body estrogen levels decrease, the milk gland tissue then atrophies, withers, and disappears, resulting in a breast composed of adipose tissue, superficial fascia, suspensory ligaments, and the skin envelope.

The dimensions and weight of the breast vary among women, ranging from approximately 500 to 1,000 grams (1.1 to 2.2 pounds) each; thus, a small-to-medium-sized breast weighs 500 grams (1.1 pounds) or less; and a large breast weighs approximately 750 to 1,000 grams (1.7 to 2.2 pounds.) The tissue composition ratios of the breast likewise vary among women; some breasts have greater proportions of glandular tissue than of adipose or connective tissues, and vice versa; therefore the fat-to-connective-tissue ratio determines the density (firmness) of the breast. In the course of a woman's life, her breasts will change size, shape, and weight, because of the hormonal bodily changes occurred in thelarche (pubertal breast development), menstruation (fertility), pregnancy (reproduction), the breast-feeding of an infant child, and the climacterium (the end of fertility).[6][7]

Glandular structure

The breast is an apocrine gland that produces milk to feed an infant child; for which the nipple of the breast is centred in (surrounded by) an areola (nipple-areola complex, NAC), the skin color of which varies from pink to dark brown, and has many sebaceous glands. The basic units of the breast are the terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs), which produce the fatty breast milk. They give the breast its offspring-feeding functions as a mammary gland. They are distributed throughout the body of the breast; approximately two-thirds of the lactiferous tissue is within 30 mm of the base of the nipple. The terminal lactiferous ducts drain the milk from TDLUs into 4–18 lactiferous ducts, which drain to the nipple; the milk-glands-to-fat ratio is 2:1 in a lactating woman, and 1:1 in a non-lactating woman. In addition to the milk glands, the breast also is composed of connective tissues (collagen, elastin), white fat, and the suspensory Cooper's ligaments. Sensation in the breast is provided by the peripheral nervous system innervation, by means of the front (anterior) and side (lateral) cutaneous branches of the fourth-, the fifth-, and the sixth intercostal nerves, while the T-4 nerve (Thoracic spinal nerve 4), which innervates the dermatomic area, supplies sensation to the nipple-areola complex.[8][9]

Lymphatic drainage

Approximately 75% of the lymph from the breast travels to the axillary lymph nodes on the same side of the body, whilst 25% of the lymph travels to the parasternal nodes (beside the sternum bone).[5] : 116 A small amount of remaining lymph travels to the other breast, and to the abdominal lymph nodes. The axillary lymph nodes include the pectoral (chest), subscapular (under the scapula), and humeral (humerus-bone area) lymph-node groups, which drain to the central axillary lymph nodes and to the apical axillary lymph nodes. The lymphatic drainage of the breasts is especially relevant to oncology, because breast cancer is a cancer common to the mammary gland, and cancer cells can metastasize (break away) from a tumour and be dispersed to other parts of the woman's body by means of the lymphatic system.

Shape and support

The morphologic variations in the size, shape, volume, tissue density, pectoral locale, and spacing of the breasts determine their natural shape, appearance, and configuration upon the chest of a woman; yet such features do not indicate its mammary-gland composition (fat-to-milk-gland ratio), nor the potential for nursing an infant child.[10][11] The size and the shape of the breasts are influenced by normal-life hormonal changes (thelarche, menstruation, pregnancy, menopause) and medical conditions (e.g. virginal breast hypertrophy).[12] The shape of the breasts is naturally determined by the support of the suspensory Cooper's ligaments, the underlying muscle and bone structures of the chest, and the skin envelope. The suspensory ligaments sustain the breast from the clavicle (collarbone) and the clavico-pectoral fascia (collarbone and chest), by traversing and encompassing the fat and milk-gland tissues, the breast is positioned, affixed to, and supported upon the chest wall, while its shape is established and maintained by the skin envelope.

The base of each breast is attached to the chest by the deep fascia over the pectoralis major muscles. The space between the breast and the pectoralis major muscle is called retromammary space and gives mobility to the breast. Some breasts are mounted high upon the chest wall, are of rounded shape, and project almost horizontally from the chest, which features are common to girls and women in the early stages of thelarchic development, the sprouting of the breasts. In the high-breast configuration, the dome-shaped and the cone-shaped breast is affixed to the chest at the base, and the weight is evenly distributed over the base area. In the low-breast configuration, a proportion of the breast weight is supported by the chest, against which rests the lower surface of the breast, thus is formed the inframammary fold (IMF). Because the base is deeply affixed to the chest, the weight of the breast is distributed over a greater area, and so reduces the weight-bearing strain upon the chest, shoulder, and back muscles that bear the weight of the bust.

The chest (thoracic cavity) progressively slopes outwards from the thoracic inlet (atop the breastbone) and above to the lowest ribs that support the breasts. The inframammary fold, where the lower portion of the breast meets the chest, is an anatomic feature created by the adherence of the breast skin and the underlying connective tissues of the chest; the IMF is the lower-most extent of the anatomic breast. In the course of thelarche, some girls develop breasts the lower skin-envelope of which touches the chest below the IMF, and some girls do not; both breast anatomies are statistically normal morphologic variations of the size and shape of women's breasts.[13]

Size

Breast size varies with race and ethnic origin. A study released in 2013 suggests the existence of a single genetic mutation responsible for multiple characteristics of East Asians, including thicker hair, more sweat glands and smaller breasts on women.[14]

Development

The basic morphological structure of the human breast – female and male – is determined during the prenatal development stage. For a girl in puberty, during thelarche (the breast-development stage), the female sex hormones (principally estrogens) promote the sprouting, growth, and development of the breasts, in the course of which, as mammary glands, they grow in size and volume, and usually rest on her chest; these development stages of secondary sex characteristics (breasts, pubic hair, etc.) are illustrated in the five-stage Tanner Scale.[15] During thelarche, the developing breasts sometimes are of unequal size, and usually the left breast is slightly larger; said condition of asymmetry is transitory and statistically normal to female physical and sexual development.[16] Moreover, breast development sometimes is abnormal, manifested either as overdevelopment (e.g. virginal breast hypertrophy) or as underdevelopment (e.g. tuberous breast deformity) in girls and women; and manifested in boys and men as gynecomastia (woman's breasts), the consequence of a biochemical imbalance between the normal levels of the estrogen and testosterone hormones of the male body.[17]

Asymmetry

Approximately two years after the onset of puberty (a girl's first menstrual cycle), the hormone estrogen stimulates the development and growth of the glandular, fat, and suspensory tissues that compose the breast. This continues for approximately four years[clarification needed] until establishing the final shape of the breast (size, volume, density) when she is a woman of approximately 21 years of age.[11] About 90% of women's breasts are asymmetrical to some degree,[11] either in size, volume, or relative position upon the chest. Asymmetry can be manifested in the size of the breast, the position of the nipple-areola complex (NAC), the angle of the breast, and the position of the inframammary fold, where the breast meets the chest.

For about 5%[11] to 10%[18] women, their breasts are severely different, with the left breast being larger in 62% of cases.[18] This is due to the breast proximity to the heart and a greater number of arteries and veins, along with a protective layer of fat surrounding the heart located beneath it.[19] Up to 25% of women experience notable breast asymmetry of at least one cup size difference.[10][11][20][21][22]

If a woman is uncomfortable with her breasts' asymmetry, she can minimize the difference with a corrective bra[19] or use gel bra inserts.[19] Alternatively, she can seek a surgical solution. Options include a minimally invasive procedure known as platelet injection fat transfer, which transfers fat cells from a woman's thighs to her smaller breast.[11] More invasive procedures include corrective mammoplasty, such as mastopexy, breast reduction plasty, or breast augmentation, depending on the nature of the asymmetry.[11][18] Most surgeons will only perform an augmentation procedure to treat asymmetry if the woman's breasts differ by at least one cup size.[11]

Hormonal change

Because the breasts are principally composed of adipose tissue, which surrounds the milk glands, their sizes and volumes fluctuate according to the hormonal changes particular to thelarche (sprouting of breasts), menstruation (egg production), pregnancy (reproduction), lactation (feeding of offspring), and menopause (end of menstruation). For example, during the menstrual cycle, the breasts are enlarged by premenstrual water retention; during pregnancy the breasts become enlarged and denser (firmer) because of the prolactin-caused organ hypertrophy, which begins the production of breast milk, increases the size of the nipples, and darkens the skin color of the nipple-areola complex; these changes continue during the lactation and the breastfeeding periods. Afterwards, the breasts generally revert to their pre-pregnancy size, shape, and volume, yet might present stretch marks and breast ptosis. At menopause, the breasts can decrease in size when the levels of circulating estrogen decline, followed by the withering of the adipose tissue and the milk glands. Additional to such natural biochemical stimuli, the breasts can become enlarged consequent to an adverse side effect of combined oral contraceptive pills; and the size of the breasts can also increase and decrease in response to the body weight fluctuations of the woman. Moreover, the physical changes occurred to the breasts often are recorded in the stretch marks of the skin envelope; they can serve as historical indicators of the increments and the decrements of the size and the volume of a woman's breasts throughout the course of her life.

Breast ptosis

Ptosis is a normal consequence of aging[23] where the breast tissue sags lower on the chest and the nipple points downward.[24] The rate at which a woman develops ptosis depends on many factors including genetics, smoking, body mass index, number of pregnancies, the size of breasts before pregnancy, and age.[25]

Plastic surgeons categorize ptosis by evaluating the position of the nipple relative to the inframammary crease (where the underside of the breast meets the chest wall). This is determined by measuring from the center of the nipple to the sternal notch (at the top of the breast bone) to gauge how far the nipple has fallen. The standard anthropometric measurement for young women is 21 centimetres (8.3 in). This measurement is used to assess both breast ptosis and breast symmetry. The surgeon will assess the breast's angle of projection. The apex of the breast, which includes the nipple, can have a flat angle of projection (180 degrees) or acute angle of projection (greater than 180 degrees). The apex rarely has an angle greater than 60 degrees. The angle of the breast apex is partly determined by the tautness of the suspensory Cooper's ligaments. For example, when a woman lies on her back, the angle of the breast apex becomes a flat, obtuse angle (less than 180 degrees) while the base-to-length ratio of the breast ranges from 0.5 to 1.0.[23]

Functions and health

Lactation

The primary function of the breasts – as mammary glands – is the feeding and the nourishing of an infant child with breast milk during the maternal lactation period. The round shape of the breast helps to limit the loss of maternal body heat, because milk production depends upon a higher-temperature environment for the proper, milk-production function of the mammary gland tissues, the lactiferous ducts. Regarding the shape of the breast, the study The Evolution of the Human Beast (2001) proposed that the rounded shape of a woman's breast evolved to prevent the sucking infant offspring from suffocating while feeding at the teat; that is, because of the human infant's small jaw, which did not project from the face to reach the nipple, he or she might block the nostrils against the mother's breast if it were of a flatter form (cf. chimpanzee); theoretically, as the human jaw receded into the face, the woman's body compensated with round breasts.[26]

In a woman, the condition of lactation unrelated to pregnancy can occur as galactorrhea (spontaneous milk flow), and because of the adverse effects of drugs (e.g. antipsychotic medications), of extreme physical stress, and of endocrine disorders. In a newborn infant, the capability of lactation is consequence of the mother's circulating hormones (prolactin, oxytocin, etc.) in his or her blood stream, which were introduced by the shared circulatory system of the placenta. In men, the mammary glands are also present in the body, but normally remain undeveloped because of the hormone testosterone, however, when male lactation occurs, it is considered a pathological symptom of a disorder of the pituitary gland.

Reproduction

In considering the human animal, zoologists proposed that the human female is the only primate that possesses permanent, full-form breasts when not pregnant. Other mammalian females develop full breasts only when pregnant.[citation needed]

Mammary diseases

The breast is susceptible to numerous benign and malignant conditions. The most frequent benign conditions are puerperal mastitis, fibrocystic breast changes and mastalgia. Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death among women.

Society and culture

Anthropomorphic geography

There are many mountains named after the breast because they resemble it in appearance and so are objects of religious and ancestral veneration as a fertility symbol and of well-being. In Asia, there was "Breast Mountain," which had a cave where the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (Da Mo) spent much time in meditation.[27] Other such breast mountains are Mount Elgon on the Uganda-Kenya border, Beinn Chìochan and the Maiden Paps in Scotland, the "Bundok ng Susong Dalaga" (Maiden's breast mountains) in Talim Island, Philippines, the twin hills known as the Paps of Anu (Dá Chích Anann or the breasts of Anu), near Killarney in Ireland, the 2,086 m high Tetica de Bacares or "La Tetica" in the Sierra de Los Filabres, Spain, and Khao Nom Sao in Thailand, Cerro Las Tetas in Puerto Rico and the Breasts of Aphrodite in Mykonos, among many others. In the United States, the Teton Range is named after the French word for "breast."[28]

Art history

In European pre-historic societies, sculptures of female figures with pronounced or highly exaggerated breasts were common. A typical example is the so-called Venus of Willendorf, one of many Paleolithic Venus figurines with ample hips and bosom. Artifacts such as bowls, rock carvings and sacred statues with breasts have been recorded from 15,000 BC up to late antiquity all across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Many female deities representing love and fertility were associated with breasts and breast milk. Figures of the Phoenician goddess Astarte were represented as pillars studded with breasts. Isis, an Egyptian goddess who represented, among many other things, ideal motherhood, was often portrayed as suckling pharaohs, thereby confirming their divine status as rulers. Even certain male deities representing regeneration and fertility were occasionally depicted with breast-like appendices, such as the river god Hapy who was considered to be responsible for the annual overflowing of the Nile. Female breasts were also prominent in the Minoan civilization in the form of the famous Snake Goddess statuettes. In Ancient Greece there were several cults worshipping the "Kourotrophos", the suckling mother, represented by goddesses such as Gaia, Hera and Artemis. The worship of deities symbolized by the female breast in Greece became less common during the first millennium. The popular adoration of female goddesses decreased significantly during the rise of the Greek city states, a legacy which was passed on to the later Roman Empire.[29]

During the middle of the first millennium BC, Greek culture experienced a gradual change in the perception of female breasts. Women in art were covered in clothing from the neck down, including female goddesses like Athena, the patron of Athens who represented heroic endeavor. There were exceptions: Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was more frequently portrayed fully nude, though in postures that were intended to portray shyness or modesty, a portrayal that has been compared to modern pin ups by historian Marilyn Yalom.[30] Although nude men were depicted standing upright, most depictions of female nudity in Greek art occurred "usually with drapery near at hand and with a forward-bending, self-protecting posture".[31] A popular legend at the time was of the Amazons, a tribe of fierce female warriors who socialized with men only for procreation and even removed one breast to become better warriors (the idea being that the right breast would interfere with the operation of a bow and arrow). The legend was a popular motif in art during Greek and Roman antiquity and served as an antithetical cautionary tale.

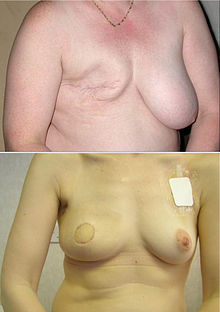

Body image

Many women regard their breasts, which are female secondary sex characteristics, as important to their sexual attractiveness, as a sign of femininity that is important to their sense of self.[citation needed] So, when a woman considers her breasts deficient in some respect, she might choose to undergo a plastic surgery procedure to enhance them, either to have them augmented or to have them reduced, or to have them reconstructed if she suffered a deformative disease, such as breast cancer.[32] After mastectomy, the reconstruction of the breast or breasts is done with breast implants or autologous tissue transfer, using fat and tissues from the abdomen, which is performed with a TRAM flap or with a back (latissiumus muscle flap). Breast reduction surgery is a procedure that involves removing excess breast tissue, fat, and skin, and the repositioning of the nipple-areola complex.

Cosmetic improvement procedures include breast lift (mastopexy), breast augmentation with implants, and combination procedures; the two types of available breast implants are models filled with silicone gel, and models filled with saline solution. These types of breast surgery can also repair inverted nipples by releasing milk duct tissues that have become tethered. Furthermore, in the case of the obese woman, a breast lift (mastopexy) procedure, with or without a breast volume reduction, can be part of an upper-body lift and contouring for the woman who has undergone massive body weight loss.

Surgery of the breast presents the health risk of interfering with the ability to breast-feed an infant child, and might include consequences such as altered sensation in the nipple-areola complex, interference with mammography (breast x-rays images) when there are breast implants present in the breasts. Regarding breast-feeding capability after breast reduction surgery, studies reported that women who underwent breast reduction can retain the ability to nurse an infant child, when compared to women in a control group who underwent breast surgery using a modern pedicle surgical technique.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39] Plastic surgery organizations generally discourage elective cosmetic breast augmentation surgery for teen-aged girls, because, at that age, the volume of the breast tissues (milk glands and fat) can continue to grow as the girl matures to womanhood. Breast reduction surgery for teen-aged girls, however, is a matter handled according to the particulars of the case of hypoplasia. (see: breast hypertrophy)

Clothing

Because breasts are mostly fatty tissue, their shape can within limits be molded by clothing, such as foundation garments. Bras are commonly worn by about 90% of Western women,[40][41][42] and are often worn for support.[43] The social norm in most Western cultures is to cover breasts in public, though the extent of coverage varies depending on the social context. Some religions ascribe a special status to the female breast, either in formal teachings or through symbolism.[citation needed] Islam forbids women from exposing their breasts in public.

Many cultures associate breasts with sexuality and tend to regard bare breasts as immodest or indecent. In some cultures, like the Himba in northern Namibia, bare-breasted women are normal, while a thigh is highly sexualised and not exposed in public. In a few Western countries female toplessness at a beach is acceptable, although it may not be acceptable in the town center. In some areas, exposing a woman's breasts applies only to the exposure of nipples.

In the United States, women who breast-feed in public can receive negative attention. There have been instances where women have been asked to leave public venues. In New York, the topfreedom equality movement helped to bring a case, People v. Santorelli (1992), to the New York State Court of Appeals. They ruled that New York's indecent exposure laws did not apply to a bare-breasted woman. Other (gender equality) efforts succeeded in most of Canada in the 1990s. Bare-breasted women are legal and culturally acceptable at public beaches in Australia and much of Europe.

Sexual characteristic

In some cultures, breasts play a role in human sexual activity. Breasts and especially the nipples are among the various human erogenous zones. They are sensitive to the touch as they have many nerve endings; and it is common to press or massage them with hands or orally before or during sexual activity. Some women can achieve an orgasm from such activities. Research has suggested that the sensations are genital orgasms caused by nipple stimulation, and may also be directly linked to "the genital area of the brain".[44][45] Sensation from the nipples travels to the same part of the brain as sensations from the vagina, clitoris and cervix. Nipple stimulation may trigger uterine contractions, which then produce a sensation in the genital area of the brain.[45] In the ancient Indian work the Kama Sutra, light scratching of the breasts with nails and biting with teeth are considered erotic.[46] During sexual arousal, breast size increases, venous patterns across the breasts become more visible, and nipples harden. Compared to other primates, human breasts are proportionately large throughout adult females' lives. Some writers have suggested that they may have evolved as a visual signal of sexual maturity and fertility.[47]

Many people regard the female human body, of which breasts are an important aspect, to be aesthetically pleasing, as well as erotic. Research conducted at the Victoria University of Wellington showed that breasts are often the first thing men look at, and for a longer time than other body parts.[48] The writers of the study had initially speculated that the reason for this is due to endocrinology with larger breasts indicating higher levels of estrogen and a sign of greater fertility,[48][49] but the researchers said that "Men may be looking more often at the breasts because they are simply aesthetically pleasing, regardless of the size."[48]

Many people regard bare female breasts to be erotic, and they can elicit heightened sexual desires in men in many cultures. Some people show a sexual interest in female breasts distinct from that of the person, which may be regarded as a breast fetish.[50] While U.S. culture prefers breasts that are youthful and upright, some cultures venerate women with drooping breasts, indicating mothering and the wisdom of experience.[51]

Symbolism

In Christian iconography, some works of art depict women with their breasts in their hands or on a platter, signifying that they died as a martyr by having their breasts severed; one example of this is Saint Agatha of Sicily.[citation needed]

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ "mammal – Definitions from Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b "SEER Training: Breast Anatomy". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Indo-European Lexicon: Pokorny Master PIE Etyma. Utexas.edu. Retrieved on 2011-04-22.

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ a b Drake, Richard L. (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pamplona DC, de Abreu Alvim C. Breast Reconstruction with Expanders and Implants: a Numerical Analysis. Artificial Organs 8 (2004), pp. 353–356.

- ^ Grassley JS. Breast Reduction Surgery: What every Woman Needs to Know. Lifelines 6 (2002), pp. 244–249.

- ^ Introduction to the Human Body, Fifth Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 2001. 560.

- ^ Ramsay DT, Kent JC, Hartmann RA, Hartmann PE (June 2005). "Anatomy of the Lactating Human Breast Redefined with Ultrasound Imaging". Journal of Anatomy. 206 (6): 525–534. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00417.x. PMC 1571528. PMID 15960763.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jelovsek, Frederick R. "Breast Asymmetry—When Does it Need Treatment?". Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goddard, Kay (10 May 2011). "I May Have Been the Ultimo Bra Girl, but One of my Breasts was a B-cup and the other was a D". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Wood K, Cameron M, Fitzgerald K (2008). "Breast Size, Bra Fit and Thoracic Pain in Young Women: A Correlational Study". Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 16: 1. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-16-1. PMC 2275741. PMID 18339205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Boutros S, Kattash M, Wienfeld A, Yuksel E, Baer S, Shenaq S (September 1998). "The Intradermal Anatomy of the Inframammary Fold". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 102 (4): 1030–1033. doi:10.1097/00006534-199809040-00017. PMID 9734420.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "East Asian Physical Traits Linked to 35,000-Year-Old Mutation".

- ^ Greenbaum AR, Heslop T, Morris J, Dunn KW (April 2003). "An Investigation of the Suitability of Bra fit in Women Referred for Reduction Mammaplasty". British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 56 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1016/S0007-1226(03)00122-X. PMID 12859918.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Loughry CW; et al. (1989). "Breast Volume Measurement of 598 Women using Biostereometric Analysis". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 22 (5): 380–385. doi:10.1097/00000637-198905000-00002. PMID 2729845.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer and History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8018-6936-5. OCLC 186453370.

- ^ a b c Losken A, Fishman I, Denson DD, Moyer HR, Carlson GW (December 2005). "An objective evaluation of breast symmetry and shape differences using 3-dimensional images". Annals of Plastic Surgery. 55 (6): 571–5. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000185459.49434.5f. PMID 16327452.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "losken" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c Ivens, Sarah (16 May 2012). "Life's a balancing act when you've an uneven bosom". DailyMail.uk. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Dolya, Gayane. "Breast Asymmetry". Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Breast Development". Massachusetts Hospital for Children. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Asymmetric Breasts". Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Breast Lift Procedure". Ricardo L. Rodriguez, MD. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Younai, S. Sean. "Breast Sagging – Ptosis". Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Campolongo, Marianne (5 December 2007). "What Causes Sagging Breasts?". Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ^ Bentley, Gillian R. (2001). "The Evolution of the Human Breast". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 32 (38): 30. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1033.

- ^ "The Story of Bodhidharma". Usashaolintemple.org. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Creation of the Teton Landscape: The Geologic Story of Grand Teton National Park (The Story Begins)". U.S. National Park Service. Last updated 19 January 2007. Retrieved 2011-09-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Yalom (1998) pp. 9–16; see Eva Keuls (1993), Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens for a detailed study of male-dominant rule in ancient Greece.

- ^ Yalom (1998), p. 18.

- ^ Hollander (1993), p. 6.

- ^ "Secondary sex characteristics". .hu-berlin.de. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Neifert, M (1990). "The influence of breast surgery, breast appearance and pregnancy-induced changes on lactation sufficiency as measured by infant weight gain". Birth. 17 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1990.tb00007.x. PMID 2288566.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "FAQ on Previous Breast Surgery and Breastfeeding". La Leche League International. 29 August 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ^ West, Diana. "Breastfeeding After Breast Surgery". Australian Breastfeeding Association. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ^ Cruz-Korchin N, Korchin L (September 2004). "Breast-feeding after vertical mammaplasty with medial pedicle". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 114 (4): 890–4. doi:10.1097/01.PRS.0000133174.64330.CC. PMID 15468394.

- ^ Brzozowski D, Niessen M, Evans HB, Hurst LN (February 2000). "Breast-feeding after inferior pedicle reduction mammaplasty". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 105 (2): 530–4. doi:10.1097/00006534-200002000-00008. PMID 10697157.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Witte, PM (26 June 2004). "Successful breastfeeding after reduction mammaplasty". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 148 (26): 1291–93. PMID 15279213.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kakagia, D; Tripsiannis G; Tsoutsos D (October 2005). "Breastfeeding after reduction mammaplasty: a comparison of 3 techniques". Ann Plast Surg. 55 (4): 343–45. doi:10.1097/01.sap.0000179167.18733.97. PMID 16186694.

- ^ "Bra Cup Sizes—getting fitted with the right size". 1stbras.com. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ "The Right Bra". Liv.com. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ "Breast supporting act: a century of the bra". London: The Independent UK. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- ^ Breast size, bra fit and thoracic pain in young women: a correlational study Retrieved 5 January 2012

- ^ Levay, Simon (15 November 2005). Human Sexuality, Second Edition. Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87893-465-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Komisaruk, B. R., Wise, N., Frangos, E., Liu, W.-C., Allen, K. and Brody, S. (2011). "Women's Clitoris, Vagina, and Cervix Mapped on the Sensory Cortex: fMRI Evidence". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (10): 2822. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02388.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sir Richard Burton's English translation of Kama Sutra". Sacred-texts.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Anders Pape Møller; et al. (1995). "Breast asymmetry, sexual selection, and human reproductive success =". Ethology and Sociobiology. 16 (3): 207–219. doi:10.1016/0162-3095(95)00002-3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Scientific proof that men look at women's breasts first and their face is almost last The Daily Telegraph

- ^ "Hourglass figure fertility link". BBC News. 4 May 2004. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ Hickey, Eric W. (2003). Encyclopaedia of Murder and Violent Crime. Sage Publications Inc. ISBN 978-0-7619-2437-1

- ^ Burns-Ardolino, Wendy (2007). Jiggle: (Re)shaping American women. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7391-1299-1.

- Bibliography

- Hollander, Anne Seeing through Clothes. University of California Press, Berkeley. 1993 ISBN 978-0-520-08231-1

- Morris, Desmond The Naked Ape: a zoologist's study of the human animal Bantam Books, Canada. 1967

- Yalom, Marilyn A History of the Breast. Pandora, London. 1998 ISBN 978-0-86358-400-8

External links

Media related to Breasts at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Breasts at Wikimedia Commons- Images of female breasts

- Breast Cancer Treatment and Facts

- "Are Women Evolutionary Sex Objects?: Why Women Have Breasts". Archived from the original on 2 December 2011.