Empire

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (January 2014) |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2013) |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium (power, authority). Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples (ethnic groups) united and ruled either by a monarch (emperor, empress) or an oligarchy.

Aside from the traditional usage, the term empire can be used in an extended sense to denote a large-scale business enterprise (e.g., a transnational corporation), or a political organisation of either national-, regional- or city scale, controlled either by a person (a political boss) or a group authority (political bosses).[1]

An imperial political structure is established and maintained in two ways: (i) as a territorial empire of direct conquest and control with force (direct, physical action to compel the emperor's goals) or (ii) as a coercive, hegemonic empire of indirect conquest and control with power (the perception that the emperor can physically enforce his desired goals). The former provides greater tribute and direct political control, yet limits further expansion because it absorbs military forces to fixed garrisons. The latter provides less tribute and indirect control, but avails military forces for further expansion.[2] Territorial empires (e.g., the Mongol Empire, the Median Empire) tended to be contiguous areas. The term on occasion has been applied to maritime empires or thalassocracies, (e.g., the Athenian and British Empires) with looser structures and more scattered territories.

Definition

An empire is a state with politico-military dominion of populations who are culturally and ethnically distinct from the imperial (ruling) ethnic group and its culture[3]—unlike a federation, an extensive state voluntarily composed of autonomous states and peoples.

What physically and politically constitutes an empire is variously defined. It might be a state effecting imperial policies, or a particular political structure. Empires are typically formed from separate components that come together. Some units include ethnic, national, cultural, and religious diversity.[4]

Tom Nairn defines empires as polities that:

extend relations of power across territorial spaces over which they have no prior or given legal sovereignty, and where, in one or more of the domains of economics, politics, and culture, they gain some measure of extensive hegemony over those spaces for the purpose of extracting or accruing value".[5]

Sometimes an empire is a semantic construction, such as when a ruler assumes the title of "Emperor". The said ruler's nation logically becomes an "Empire", despite having no additional territory or hegemony such as Central African Empire or the Korean Empire proclaimed in 1897 when Korea, far from gaining new territory was on the verge of being annexed by the Empire of Japan, the last to use the name officially. Amongst the last of these empires of the 20th century were the Central African Empire, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Manchukuo, the German Empire, and Korea.

The terrestrial empire's maritime analogue is the thalassocracy, an empire comprising islands and coasts which are accessible to its terrestrial homeland, such as the Athenian-dominated Delian League.

Characteristics

Empires accreted to different types of states, although they commonly originated as powerful monarchies. The Athenian Empire, the Roman Empire and the British Empire developed under elective auspices. The Empire of Brazil declared itself an empire after breaking from the Portuguese Empire in 1822. France has twice transited from being called the French Republic to being called the French Empire, while France remained an overseas empire.

Many empires resulted from military conquest, incorporating the vanquished states to its political union. A state could establish imperial hegemony in other ways. A weak state may seek annexation into the empire. For example, the bequest of Pergamon by Attalus III, to the Roman Empire. The Unification of Germany as the empire accreted to the Prussian metropole was less a military conquest of the German states than their political divorce from the Austrian Empire. Having convinced the other states of its military prowess — and having excluded the Austrians — Prussia dictated the terms of imperial membership.

Politically it was typical for either a monarchy or an oligarchy, rooted in the original core territory of the empire, to continue to dominate. If government was maintained via control of water vital to the colonial subjects, such régimes were called hydraulic empires.

Europeans began applying the name of "empire" to non-European monarchies, such as the Qing Dynasty and the Mughal Empire as well as Maratha Empire, and then leading, eventually, to the looser denotations applicable to any political structure meeting the criteria of imperium.

Some empires styled themselves as having greater size, scope and power than the territorial, politico-military and economic facts allow. As a consequence some monarchs assumed the title of "emperor" (or its corresponding translation: tsar, empereur, kaiser, etc.) and renamed their states as "The Empire of ...".

When possible, empires used a common religion or culture to strengthen the political structure.

History of imperialism

Early empires

|

|

The Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great (24th century BC), was an early large empire. In the 15th century BC, the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, ruled by Thutmose III, was ancient Africa's major force upon incorporating Nubia and the ancient city-states of the Levant. The first empire comparable to Rome in organization was the Assyrian empire (2000–612 BC). The Median Empire was the first empire on the territory of Persia. By the 6th century BC, after having allied with the Babylonians to defeat the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the Medes were able to establish their own empire, the largest of its day, lasting for about sixty years. The successful, extensive, and multi-cultural empire that was the Persian Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC) absorbed Mesopotamia, Egypt, parts of Greece, Thrace, the Middle East, and much of Central Asia and Pakistan, until it was overthrown and replaced by the short-lived empire of Alexander the Great.

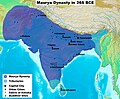

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive and powerful empire in ancient India, ruled by the Mauryan dynasty from 321 to 185 BC. The Empire was founded in 322 BC by Chandragupta Maurya who rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India, taking advantage of the disruptions of local powers in the wake of the withdrawal westward by Alexander the Great. By 320 BC, the empire had fully occupied past northwestern India as well as defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander. It has been estimated that the Maurya Dynasty controlled an unprecedented one-third of the world's entire economy, was home to one-third of the world's population at the time (an estimated 50 million out of 150 million humans), contained the world's largest city of the time (Pataliputra, estimated to be larger than Rome under Emperor Trajan) and according to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants.

Classical period

|

|

In western Asia, the term Persian Empire denotes the Iranian imperial states established at different historical periods of pre–Islamic and post–Islamic Persia. And in East Asia, various Celestial Empires arose periodically between periods of war, civil war, and foreign conquests. In India Chandragupta expanded the Mauryan Empire to Northwest India (modern day Pakistan and Afghanistan). This also included the era of expansion of Buddhism under Ashoka the Great. In China the Han Empire became one of East Asia's most long lived dynasties, but was preceded by the short-lived Qin Empire. The kingdom of Macedonia, under Alexander the Great, became an empire that spanned from Greece to Northwestern India. After Alexander's death, his empire fractured into four, discrete kingdoms ruled by the Diadochi, which, despite being independent, are denoted as the "Hellenistic Empire" by virtue of their similarity in culture and administration. These successor empires were ultimately absorbed into the Roman Empire.

The Roman Empire was the most extensive Western empire until the early modern period, and has left a lasting impact on the Western European nations to this day, as many of their languages, cultural values, religious institutions, political divisions, urban centers, and legal systems can trace their origins to the Roman Empire. The Latin word imperium, referring to a magistrate's power to command, gradually assumed the meaning "The territory in which a magistrate can effectively enforce his commands," while the term imperator, originally was an honorific given to those generals victorious in battle, meaning "commander." Thus, an "empire" may include regions that are not legally within the territory of a state, but are under direct, or indirect, control of that state, such as a colony, client state, or protectorate. Although historians refer to the "Republican period," and the "Imperial period" of Roman history to identify the periods before, and after, absolute power was assumed by Augustus, the Romans themselves continued to refer to their government as a "Republic," and during the Republican Period, the territories controlled by the Republic were referred to as "Imperium Romanum". The Emperor's actual legal power derived from holding the office of "consul," but he was traditionally honored with the titles of Imperator ("commander"), and Princeps ("first man" / "chief"). Later, these terms came to have legal significance in their own right; an army acclaiming their general "imperator" was offering a direct challenge to the authority of the current Emperor.[6]

The legal systems of France, and her former colonies, are strongly influenced by Roman law,[7] while the United States was expressly founded on a model inspired by the Roman Republic, with upper, and lower, legislative assemblies, and executive power invested in single individual, in the person of the President, as "commander-in-chief" of the armed forces, reflecting the ancient Roman titles imperator princeps.[8] The Roman Catholic Church, founded in the early Imperial period, spread across Europe, first by the activities of Christian evangelists, later by official Imperial promulgation.

Post-classical period

|

|

|

|

The 7th century saw the emergence of the Islamic Empire, also referred to as the Arab Empire. The Rashidun Caliphate expanded from the Arabian Peninsula and swiftly conquered the Persian Empire and much of the Byzantine Roman Empire. Its successor state, the Umayyad Caliphate, expanded across North Africa and into the Iberian Peninsula. By the beginning of the 8th century, it had become the largest empire in history at that point, until it was eventually surpassed in size by the Mongol Empire in the 13th century. In the 7th century, Maritime Southeast Asia witnessed the rise of a Buddhist thallasocracy—the Srivijaya Empire—which thrived for 600 years, and was succeeded by the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit Empire in the 13th to 15th century. In the Southeast Asian mainland, the Hindu-Buddhist Khmer Empire built an empire centered in the city of Angkor and which flourished from the 9th to 13th century. Followed by the sack of Khmer Empire, the Siamese Empire was flourished alongside the Burmese and Lan Chang Empire from 13th through to 18th century . In Eastern Europe the Byzantine Empire had to recognize the Imperial title of the Bulgarian rulers in 917 (through a Bulgarian Tsar). The Bulgarian Empire remained a major power in the Balkans until its fall in the late 14th century.

At the time, in the Medieval West, the title "empire" had a specific technical meaning that was exclusively applied to states that considered themselves the heirs and successors of the Roman Empire, e.g. the Byzantine Empire which was the actual continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire, and later the Carolingian Empire, the largely Germanic Holy Roman Empire, the Russian Empire, yet these states were not always technically—geographic, political, military—empires in the modern sense of the word. To legitimise their imperium, these states directly claimed the title of Empire from Rome. The sacrum Romanum imperium (Holy Roman Empire) of 800 to 1806, claimed to have exclusively comprehended Christian principalities, and was only nominally a discrete imperial state. The Holy Roman Empire was not always centrally-governed, as it had neither core nor peripheral territories, and was not governed by a central, politico-military élite—hence, Voltaire's remark that the Holy Roman Empire "was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire" is accurate to the degree that it ignores[9] German rule over Italian, French, Provençal, Polish, Flemish, Dutch, and Bohemian populations, and the efforts of the ninth-century Holy Roman Emperors (i.e., the Ottonians) to establish central control; thus, Voltaire's "... nor an empire" observation applies to its late period.

In 1204, after the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople, the crusaders established a Latin Empire (1204–1261) in that city, while the defeated Byzantine Empire's descendants established two, smaller, short-lived empires in Asia Minor: the Empire of Nicaea (1204–1261) and the Empire of Trebizond (1204–1461). Constantinople was retaken by the Byzantine successor state centered in Nicaea in 1261, re-establishing the Byzantine Empire until 1453, by which time the Turkish-Muslim Ottoman Empire (ca. 1300–1918), had conquered most of the region. Moreover, Eastern Orthodox imperialism was not re-established until the coronation, in 1721, of Peter the Great as Emperor of Russia. Like-wise, with the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire, in 1806, during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), the Austrian Empire (1804–1867), emerged reconstituted as the Empire of Austria–Hungary (1867–1918), having "inherited" the imperium of Central and Western Europe from the losers of said wars.

The Mongol Empire, under Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century, was forged as the largest contiguous empire in the world. Genghis Khan's grandson, Kublai Khan, was proclaimed emperor, and established his imperial capital at Beijing; however, in his reign, the empire became fractured into four, discrete khanates. Nevertheless, the emergence of the Pax Mongolica had significantly eased trade and commerce across Asia.[10][11]

In Oceania Tonga Empire was a lonely empire that existed many centuries since Medieval till Modern period.

Colonial empires

European landings in the so-called "New World" (first, the Americas and later, Australia) in the 15th century, along with the Portuguese's travels around the Cape of Good Hope and along the southeast Indian Ocean coast of Africa, proved ripe opportunities for the continent's Renaissance-era monarchies to launch colonial empires like those of the ancient Romans and Greeks. In the Old World, colonial imperialism was attempted, effected and established upon the Canary Islands and Ireland. These conquered lands and peoples became de jure subordinates of the empire, rather than de facto imperial territory and subjects. Such subjugation often elicited "client-state" resentment that the empire unwisely ignored, leading to the collapse of the European colonial imperial system in the late-19th century and the early- and mid-20th century. Spanish discovery of the New World gave way to many expeditions led by England, Portugal, France, the Dutch Republic and Spain. In the 18th century, the Spanish Empire was at its height because of the great mass of goods taken from conquered territory in the Americas (Mexico, parts of the United States, the Caribbean, most of Central America and South America) and the Philippines.

Modern period

|

|

|

|

|

The French emperors Napoleon I and Napoleon III (See: Premier Empire, Second French Empire and French colonial empire) each attempted establishing a western imperial hegemony based in France. The German Empire (1871–1918), another "heir to the Holy Roman Empire" arose in 1871.

The Ashanti Empire (or Confederacy), also Asanteman (1701–1896) was a West Africa state of the Ashanti, the Akan people of the Ashanti Region, Akanland in modern day Ghana. The Ashanti (or Asante) were a powerful, militaristic and highly disciplined people in West Africa. Their military power, which came from effective strategy and an early adoption of European firearms, created an empire that stretched from central Akanland (in modern-day Ghana) to present day Benin and Côte d'Ivoire, bordered by the Dagomba kingdom to the north and Dahomey to the east. Due to the empire's military prowess, sophisticated hierarchy, social stratification and culture, the Ashanti empire had one of the largest historiographies of any indigenous Sub-Saharan African political entity.

The Sikh Empire (1799–1846) was established in the Punjab. It collapsed when the founder, Ranjit Singh, died and their army fell to the British. During the same period, Maratha Empire or the Maratha Confederacy was a Hindu state located in present-day India. It existed from 1674 to 1818 and at its peak the empire's territories covered much of South Asia. The empire was founded and consolidated by Shivaji. After the death of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb it expanded greatly under the rule of the Peshwas. In 1761, the Maratha army lost the Third Battle of Panipat which halted the expansion of the empire. Later, the empire was divided into a confederacy of Maratha states which eventually were lost to the British in the Anglo-Maratha wars by 1818.[13]

The British established their first empire (1583–1783) in North America by colonising lands that included parts of Canada and the Thirteen Colonies. In 1776, the Continental Congress of the Thirteen Colonies declared itself independent from the British Empire thus beginning the American Revolution. Britain turned towards Asia, the Pacific and later Africa with subsequent exploration leading to the rise of the second British Empire (1783–1815), which was followed by the industrial revolution and Britain's imperial century (1815–1914).[14]

Transition from empire

In time, an empire may metamorphose to another form of polity. To wit, the Holy Roman Empire, a German re-constitution of the Roman Empire, metamorphosed into various political structures (i.e., federalism), and eventually, under Habsburg rule, re-constituted itself as the Austrian Empire—an empire of much different politics and vaster extension.

An autocratic empire can become a republic (e.g., the Central African Empire in 1979); or it can become a republic with its imperial dominions reduced to a core territory (e.g., Weimar Germany, 1918–1919 and the Ottoman Empire, 1918–1923). The dissolution of the Austro–Hungarian Empire, after 1918, is an example of a multi-ethnic superstate broken into its constituent states: the republics, kingdoms, and provinces of Austria, Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czechoslovakia, Ruthenia, Galicia, et al.

After the Second World War (1939–1945) the process was commonly known as decolonisation. The British Empire evolved into a loose, multi-national Commonwealth of Nations; while the French colonial empire metamorphosed to a Francophone commonwealth. The French territory of Kwang-Chou-Wan was handed back to China in 1946. The British handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997 after 150 years of rule. The Portuguese territory of Macau was handed back to China in 1999. Macau and Hong Kong were not organised into the provincial structure of China, they have an autonomous system of government as Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China.

France still governs colonies (French Guyana, Martinique, Réunion, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, St Martin, St pierre et miquelon, Guadeloupe, TAAF, Wallis and Futuna, Saint Barthélemy, Mayotte) and exerts an hegemony in Francophone Africa (29 francophone countries such as Chad, Rwanda, et cetera). Fourteen British Overseas Territories remain under British sovereignty. Sixteen countries of the Commonwealth of Nations share their head of state, Queen Elizabeth II, as Commonwealth realms.

Contemporary usage

Contemporaneously, the concept of Empire is politically valid, yet is not always used in the traditional sense; for example Japan is considered the world's sole remaining empire because of the continued presence of the Japanese Emperor in national politics. Despite the semantic reference to Imperial power, Japan is a de jure constitutional monarchy, with a homogeneous population of 127 million people that is 98.5 per cent ethnic Japanese, making it one of the largest nation-states.[15]

Characterizing some aspects of American foreign policy and international behavior "American Empire" is controversial but not uncommon. Stuart Creighton Miller posits that the public's sense of innocence about Realpolitik (cf. American Exceptionalism) impairs popular recognition of US imperial conduct. Since it governed other countries via surrogates—domestically-weak, right-wing governments that collapse without US support.[16] G.W. Bush's Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said: "We don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic; we never have been"[17]—directly contradicts Thomas Jefferson, in the 1780s, awaiting the fall of the Spanish empire: "...till our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece".[18][19][20] In turn, historian Sidney Lens argues that from its inception the US has used every means to dominate other nations.[21]

Since the European Union began, in 1993, as a west European trade bloc, it has established its own currency, the Euro, in 1999, established discrete military forces, and exercised its limited hegemony in parts of eastern Europe and Asia. This behaviour, the political scientist Jan Zielonka suggests, is imperial, because it coerces its neighbour countries to adopt its European economic, legal, and political structures.[22][23][24][25][26][27]

In his book review of Empire (2000) by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Mehmet Akif Okur posits that, since the 11 September 2001, terrorist attacks in the U.S., the international relations determining the world's balance of power (political, economic, military) have been altered. These alterations include the intellectual (political science) trends that perceive the contemporary world's order via the re-territorrialisation of political space, the re-emergence of classical imperialist practices (the "inside" vs. "outside" duality, cf. the Other), the deliberate weakening of international organisations, the restructured international economy, economic nationalism, the expanded arming of most countries, the proliferation of nuclear weapon capabilities and the politics of identity emphasizing a state's subjective perception of its place in the world, as a nation and as a civilisation. The United States is in many ways a new kind of entity in the geopolitical bestiary: a destabilizing hegemon, a revolutionary empire.[28] These changes constitute the "Age of Nation Empires"; as imperial usage, nation-empire denotes the return of geopolitical power from global power blocs to regional power blocs (i.e., centred upon a "regional power" state [China, Russia, U.S., et al.]) and regional multi-state power alliances (i.e., Europe, Latin America, South East Asia). Nation-empire regionalism claims sovereignty over their respective (regional) political (social, economic, ideologic), cultural and military spheres.[29]

Timeline of empires

The chart below shows a timeline of polities which have been called empires. Dynastic changes are marked with a white line.

- The Roman Empire's timeline listed below is only up to the timeline of the Western part.

- The Byzantine continuation of the Roman Empire is listed separately.

- The Empires of Nicaea and Trebizond were Byzantine successor states.

See also

|

Lists:

|

References

Notes

- ^ "definition of empire from Oxford Dictionaries Online". Oxford Dictionary. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Ross Hassig, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest (1994), pp. 23–24, ISBN 0-582-06829-0 (pbk)

- ^ The Oxford English Reference Dictionary, Second Edition (2001), p. 461, ISBN 0-19-860046-1

- ^ Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-19-280223-1.

- ^ James, Paul; Nairn, Tom (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 1: Globalizing Empires, Old and New. London: Sage Publications. p. xxiii.

- ^ Michael Burger (2008). The Shaping of Western Civilization: From Antiquity to the Enlightenment. University of Toronto Press. p. 115.

- ^ Ken Pennington. "France - Legal History". Columbus School of Law and School of Canon Law, The Catholic University of America. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ^ Cynthia Haven (February 19, 2010). "Stanford scholar links Rome and America in Philadelphia exhibition". Stanford Report.

- ^ Voltaire, Wikiquote, citing Essai sur l'histoire generale et sur les moeurs et l'espirit des nations, Chapter 70 (1756), retrieved 2008-01-06

- ^ Gregory G. Guzman, "Were the barbarians a negative or positive factor in ancient and medieval history?", The Historian 50 (1988), 568–70

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen, Culture and conquest in Mongol Eurasia, 211

- ^ Wilbur, Marguerite Eyer; Company, The East India. The East India Company: And the British Empire in the Far East. Stanford University Press. pp. 175–178. ISBN 9780804728645. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - ^ Pagadi, Setumadhavarao R. (1983). Shivaji. National Book Trust, India. p. 21. ISBN 81-237-0647-2.

- ^ British Empire

- ^ George Hicks, Japan's hidden apartheid: the Korean Minority and the Japanese, (Aldershot, England; Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 1998), 3.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers, Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (2000), pp.72–9

- ^ Niall Ferguson. "Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire".

- ^ Sidney Lens; Howard Zinn (2003). The forging of the American empire: from the revolution to Vietnam, a history of U.S. imperialism. Pluto Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-7453-2100-4.

- ^ LaFeber, Walter, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America (1993) 2nd edition, p. 19

- ^ Boot, Max (May 6, 2003). "American Imperialism? No Need to Run Away from Label". Council on Foreign Relations op-ed, quoting USA Today. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lens & Zinn 2003, p. Back cover

- ^ Ian Black (December 20, 2002). "Living in a euro wonderland". Guardian. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ "EU gets its military fist". BBC News. December 13, 2002. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Nikolaos Tzifakis (April 2007). "EU's region-building and boundary-drawing policies: the European approach to the Southern Mediterranean and the Western Balkans 1". Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans. 9 (1). informaworld: 47–64. doi:10.1080/14613190701217001. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ Stephen R. Hurt (2003). "Co-operation and coercion? The Cotonou Agreement between the European Union and acp states and the end of the Lomé Convention" (PDF). Third World Quarterly. 24. informaworld: 161–176. doi:10.1080/713701373. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ^ "Europeanisation and Conflict Resolution: Case Studies from the European Periphery" (PDF). Belgian Science Policy. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Jan Zielonka (2006). Europe as Empire: The Nature of the Enlarged European Union (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-929221-3. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Charles T. Mathewes (2010). The Republic of Grace: Augustinian Thoughts for Dark Times. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8028-6508-3. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ For the Okur's thesis about "nation empires", look at the article: Mehmet Akif Okur, Rethinking Empire After 9/11: Towards A New Ontological Image of World Order Perceptions, Journal of International Affairs, Volume XII, Winter 2007, pp. 61–93

Bibliography

- Gilpin, Robert War and Change in World Politics pp. 110–116

- Geiss, Imanuel (1983). War and Empire in the Twentieth Century. Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-08-030387-0.

- Johan Galtung (January 1996). "The Decline and Fall of Empires: A Theory of De-Development". Honolulu. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2008-01-06. Written for the United Nations Research Institute on Development, UNRISD, Geneva.

- James, Paul; Nairn, Tom (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 1: Globalizing Empires, Old and New. London: Sage Publications.

- Lens, Sidney; Zinn, Howard (2003). The Forging of the American Empire: From the Revolution to Vietnam: A History of American Imperialism. Pluto press. ISBN 0-7453-2100-3.

- Bowden, Brett (2009). The Empire of Civilization: The Evolution of an Imperial Idea. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06814-5.

Further reading

- Innis, Harold (1950, rev. 1972). Empire and Communications. Rev. by Mary Q. Innis; foreword by Marshall McLuhan. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press. xii, 184 p. N.B.: "Here he [i.e., Innis] develops his theory that the history of empires is determined to a large extent by their means of communication."—From the back cover of the book's pbk. ed. ISBN 0-8020-6119-2 pbk

External links

- Index of Colonies and Possessions

- Gavrov, Sergey Modernization of the Empire. Social and Cultural Aspects of Modernization Processes in Russia ISBN 978-5-354-00915-2

- Mehmet Akif Okur, Rethinking Empire After 9/11: Towards A New Ontological Image of World Order, Perceptions, Journal of International Affairs, Volume XII, Winter 2007, pp.61-93

![In the year 1690, the realms of the Mughal Empire spanned from Kabul to Cape Comorin.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/India_in_1700_Joppen.jpg/83px-India_in_1700_Joppen.jpg)