Celts

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Celts (/ˈkɛlts/, occasionally /ˈsɛlts/, see pronunciation of Celtic) were people in Iron Age and Medieval Europe who spoke Celtic languages and had cultural similarites,[1] although the relationship between ethnic, linguistic and cultural factors in the Celtic world remains uncertain and controversial.[2] The exact geographic spread of the ancient Celts is also disputed; in particular, the ways in which the Iron Age inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland should be regarded as Celts has become a subject of controversy.[1][2][3][4]

The history of pre-Celtic Europe remains very uncertain. According to one theory, the common root of the Celtic languages, a language known as Proto-Celtic, arose in the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of Central Europe, which flourished from around 1200 BC.[5] In addition, according to a theory proposed in the 19th century, the first people to adopt cultural characteristics regarded as Celtic were the people of the Iron Age Hallstatt culture in central Europe (c. 800–450 BC), named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria.[5][6] Thus this area is sometimes called the 'Celtic homeland'. By or during the later La Tène period (c. 450 BC up to the Roman conquest), this Celtic culture was supposed to have expanded by diffusion or migration to the British Isles (Insular Celts), France and The Low Countries (Gauls), Bohemia, Poland and much of Central Europe, the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberians, Celtici, Lusitanians and Gallaeci) and Italy (Canegrate, Golaseccans and Cisalpine Gauls)[7] and, following the Gallic invasion of the Balkans in 279 BC, as far east as central Anatolia (Galatians).[8]

The earliest undisputed direct examples of a Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions, beginning in the 6th century BC.[9] Continental Celtic languages are attested almost exclusively through inscriptions and place-names. Insular Celtic is attested beginning around the 4th century AD through Ogham inscriptions, although it was clearly being spoken much earlier. Celtic literary tradition begins with Old Irish texts around the 8th century. Coherent texts of Early Irish literature, such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley), survive in 12th-century recensions.

By the mid 1st millennium AD, with the expansion of the Roman Empire and the Great Migrations (Migration Period) of Germanic peoples, Celtic culture and Insular Celtic had become restricted to Ireland, the western and northern parts of Great Britain (Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall), the Isle of Man, and Brittany. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the Celtic-speaking communities in these Atlantic regions emerged as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity. They had a common linguistic, religious, and artistic heritage that distinguished them from the culture of the surrounding polities.[10] By the 6th century, however, the Continental Celtic languages were no longer in wide use.

Insular Celtic culture diversified into that of the Gaels (Irish, Scottish and Manx) and the Brythonic Celts (Welsh, Cornish, and Bretons) of the medieval and modern periods. A modern "Celtic identity" was constructed as part of the Romanticist Celtic Revival in Great Britain, Ireland, and other European territories, such as Portugal and Spanish Galicia.[11] Today, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton are still spoken in parts of their historical territories, and Cornish and Manx are undergoing a revival.

Names and terminology

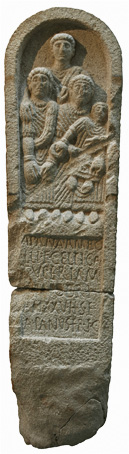

F(ilia)·CELTICA / SUPERTAM(arica)· /

(j) MIOBRI· / AN(norum)·

XXV·H(ic)·S(ita)·E(st)· / APANUS·FR(ater)·

F(aciendum)·C(uravit)”

The first recorded use of the name of Celts – as Κελτοί – to refer to an ethnic group was by Hecataeus of Miletus, the Greek geographer, in 517 BC,[12] when writing about a people living near Massilia (modern Marseille).[13] According to the testimony of Julius Caesar and Strabo, the Latin name Celtus (pl. Celti or Celtae) and the Greek [Κέλτης] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (pl. [Κέλται] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) or [Κελτός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (pl. [Κελτοί] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) were borrowed from a native Celtic tribal name.[14][15] Pliny the Elder cited its use in Lusitania as a tribal surname,[16] which epigraphic findings have confirmed.[17][18] More generally, Raimund Karl (2010) provides the current commonly agreed definition of what a Celt is:

"... a Celt is someone who either speaks a Celtic language or uses or produces Celtic art or material culture [music, etc.] or has been referred to as one in historical records or ... has been identified by others as such."[19]

Latin Gallus (pl. Galli) might also stem from a Celtic ethnic or tribal name originally, perhaps one borrowed into Latin during the Celtic expansions into Italy during the early 5th century BC. Its root may be the Common Celtic *galno, meaning “power, strength”, hence Old Irish gal “boldness, ferocity” and Welsh gallu “to be able, power”. The tribal names of Gallaeci and the Greek Γαλάται (Galatai, Latinized Galatae; see the region Galatia in Anatolia) most probably go with the same origin.[20] The suffix -atai might be an Ancient Greek inflection.[21] Classical writers did not apply the terms Κελτοί or "Celtae" to the inhabitants of Britain or Ireland,[1][2][3] which has led to some scholars preferring not to use the term for the Iron Age inhabitants of those islands.[1][2][3][4]

Celt is a modern English word, first attested in 1707, in the writing of Edward Lhuyd, whose work, along with that of other late 17th-century scholars, brought academic attention to the languages and history of the early Celtic inhabitants of Great Britain.[22] The English form Gaul (first recorded in the 17th century) and Gaulish come from the French Gaule and Gaulois, a borrowing from Frankish *Walholant, "Land of foreigners or Romans" (see Gaul: Name), the root of which is Proto-Germanic *walha-, “foreigner”', or “Celt”, whence the English word Welsh (Anglo-Saxon wælisċ < *walhiska-), South German welsch, meaning “Celtic speaker”, “French speaker” or “Italian speaker” in different contexts, and Old Norse valskr, pl. valir, “Gaulish, French”). Proto-Germanic *walha is derived ultimately from the name of the Volcae,[23] a Celtic tribe who lived first in the South of Germany and emigrated then to Gaul.[24] This means that English Gaul, despite its superficial similarity, is not actually derived from Latin Gallia (which should have produced **Jaille in French), though it does refer to the same ancient region.

Celtic refers to a family of languages and, more generally, means “of the Celts” or “in the style of the Celts”. Several archaeological cultures are considered Celtic in nature, based on unique sets of artefacts. The link between language and artefact is aided by the presence of inscriptions.[25] (See Celtic (disambiguation) for other applications of the term.) The relatively modern idea of an identifiable Celtic cultural identity or "Celticity" generally focuses on similarities among languages, works of art, and classical texts,[26] and sometimes also among material artefacts, social organisation, homeland and mythology.[27] Earlier theories held that these similarities suggest a common racial origin for the various Celtic peoples, but more recent theories hold that they reflect a common cultural and language heritage more than a genetic one. Celtic cultures seem to have been widely diverse, with the use of a Celtic language being the main thing they have in common.[1]

Today, the term Celtic generally refers to the languages and respective cultures of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany, also known as the Celtic nations. These are the regions where four Celtic languages are still spoken to some extent as mother tongues. The four are Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh, and Breton; plus two recent revivals, Cornish (one of the Brythonic languages) and Manx (one of the Goidelic languages). There are also attempts to reconstruct the Cumbric language (a Brythonic language from North West England and South West Scotland). Celtic regions of Continental Europe are those whose residents claim a Celtic heritage, but where no Celtic language has survived; these areas include the western Iberian Peninsula, i.e. Portugal, and north-central Spain (Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, Castile and León, Extremadura).[28] (See also: Modern Celts.)

Continental Celts are the Celtic-speaking people of mainland Europe and Insular Celts are the Celtic-speaking peoples of the British and Irish islands and their descendants. The Celts of Brittany derive their language from migrating insular Celts, mainly from Wales and Cornwall, and so are grouped accordingly.[29]

Origins

The Celtic languages form a branch of the larger Indo-European family. By the time speakers of Celtic languages enter history around 400 BC, they were already split into several language groups, and spread over much of Western continental Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, Ireland and Britain.

Some scholars think that the Urnfield culture of Western Middle Europe represents an origin for the Celts as a distinct cultural branch of the Indo-European family.[5] This culture was preeminent in central Europe during the late Bronze Age, from c. 1200 BC until 700 BC, itself following the Unetice and Tumulus cultures. The Urnfield period saw a dramatic increase in population in the region, probably due to innovations in technology and agricultural practices. The Greek historian Ephoros of Cyme in Asia Minor, writing in the 4th century BC, believed that the Celts came from the islands off the mouth of the Rhine and were "driven from their homes by the frequency of wars and the violent rising of the sea".

The spread of iron-working led to the development of the Hallstatt culture directly from the Urnfield (c. 700 to 500 BC). Proto-Celtic, the latest common ancestor of all known Celtic languages, is considered by this school of thought to have been spoken at the time of the late Urnfield or early Hallstatt cultures, in the early 1st millennium BC. The spread of the Celtic languages to Iberia, Ireland and Britain would have occurred during the first half of the 1st millennium BC, the earliest chariot burials in Britain dating to c. 500 BC. Other scholars see Celtic languages as covering Britain and Ireland, and parts of the Continent, long before any evidence of "Celtic" culture is found in archaeology. Over the centuries the language(s) developed into the separate Celtiberian, Goidelic and Brythonic languages.

The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the La Tène culture of central Europe, which was overrun by the Roman Empire, though traces of La Tène style are still to be seen in Gallo-Roman artefacts. In Britain and Ireland La Tène style in art survived precariously to re-emerge in Insular art. Early Irish literature casts light on the flavour and tradition of the heroic warrior elites who dominated Celtic societies. Celtic river-names are found in great numbers around the upper reaches of the Danube and Rhine, which led many Celtic scholars to place the ethnogenesis of the Celts in this area. A recent book about an ancient site in northern Germany, concludes that it was the most significant Celtic sacred site in Europe. It is called the "Externsteine", the strange carvings and astronomical orientation of the chambers of this site are presented as solid evidence for a Celtic origin. In view of the large number of sites excavated in recent years in Germany, and formally defined as 'Celtic", Pryor's research appears to be on solid ground. (Damien Pryor, The Externsteine, 2011, Threshold Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9581341-7-0 )

Diodorus Siculus and Strabo both suggest that the heartland of the people they called Celts was in southern France. The former says that the Gauls were to the north of the Celts, but that the Romans referred to both as Gauls (in linguistic terms the Gauls were certainly Celts). Before the discoveries at Hallstatt and La Tène, it was generally considered that the Celtic heartland was southern France, see Encyclopædia Britannica for 1813.

Linguistic evidence

The Proto-Celtic language is usually dated to the Late Bronze Age.[5] The earliest records of a Celtic language are the Lepontic inscriptions of Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy), the oldest of which still predate the La Tène period. Other early inscriptions, appearing from the early La Tène period in the area of Massilia, are in Gaulish, which was written in the Greek alphabet until the Roman conquest. Celtiberian inscriptions, using their own Iberian script, appear later, after about 200 BC. Evidence of Insular Celtic is available only from about 400 AD, in the form of Primitive Irish Ogham inscriptions.

Besides epigraphical evidence, an important source of information on early Celtic is toponymy.[30]

Archaeological evidence

Before the 19th century, scholars[who?] assumed that the original land of the Celts was west of the Rhine, more precisely in Gaul, because it was where Greek and Roman ancient sources, namely Caesar, located the Celts. This view was challenged by the 19th-century historian Marie Henri d'Arbois de Jubainville [citation needed] who placed the land of origin of the Celts east of the Rhine. Jubainville based his arguments on a phrase of Herodotus' that placed the Celts at the source of the Danube, and argued that Herodotus had meant to place the Celtic homeland in southern Germany. The finding of the prehistoric cemetery of Hallstat in 1846 by Johan Ramsauer and the finding of the archaeological site of La Tène by Hansli Kopp in 1857 drew attention to this area.

The concept that the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures could be seen not just as chronological periods but as "Culture Groups", entities composed of people of the same ethnicity and language, started to grow by the end of the 19th century. In the beginning of the 20th century the belief that those "Culture Groups" could be thought in racial or ethnic terms was strongly held by Gordon Childe whose theory was influenced by the writings of Gustaf Kossinna.[31] Along the 20th century the racial ethnic interpretation of La Tène culture rooted much stronger, and any findings of "La Tène culture" and "flat inhumation cemeteries" were directly associated with the celts and the Celtic language.[32] The Iron Age Hallstatt (c. 800–475 BC) and La Tène (c. 500–50 BC) cultures are typically associated with Proto-Celtic and Celtic culture.[33]

In various[clarification needed] academic disciplines the Celts were considered a Central European Iron Age phenomenon, through the cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. However, archaeological finds from the Halstatt and La Tène culture were rare in the Iberian Peninsula, in southwestern France, northern and western Britain, southern Ireland and Galatia[34][35] and did not provide enough evidence for a cultural scenario comparable to that of Central Europe. It is considered equally difficult to maintain that the origin of the Peninsular Celts can be linked to the preceding Urnfield culture, leading to a more recent approach that introduces a 'proto-Celtic' substratum and a process of Celticisation having its initial roots in the Bronze Age Bell Beaker culture.[36]

The La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC) in eastern France, Switzerland, Austria, southwest Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. It developed out of the Hallstatt culture without any definite cultural break, under the impetus of considerable Mediterranean influence from Greek, and later Etruscan civilisations. A shift of settlement centres took place in the 4th century.

The western La Tène culture corresponds to historical Celtic Gaul. Whether this means that the whole of La Tène culture can be attributed to a unified Celtic people is difficult to assess; archaeologists have repeatedly concluded that language, material culture, and political affiliation do not necessarily run parallel. Frey notes that in the 5th century, "burial customs in the Celtic world were not uniform; rather, localised groups had their own beliefs, which, in consequence, also gave rise to distinct artistic expressions".[38] Thus, while the La Tène culture is certainly associated with the Gauls, the presence of La Tène artefacts may be due to cultural contact and does not imply the permanent presence of Celtic speakers.

Historical evidence

Polybius published a history of Rome about 150 BC in which he describes the Gauls of Italy and their conflict with Rome. Pausanias in the 2nd century AD says that the Gauls "originally called Celts", "live on the remotest region of Europe on the coast of an enormous tidal sea". Posidonius described the southern Gauls about 100 BC. Though his original work is lost it was used by later writers such as Strabo. The latter, writing in the early 1st century AD, deals with Britain and Gaul as well as Hispania, Italy and Galatia. Caesar wrote extensively about his Gallic Wars in 58–51 BC. Diodorus Siculus wrote about the Celts of Gaul and Britain in his 1st-century history.

Minority views

Myles Dillon and Nora Kershaw Chadwick accepted that "the Celtic settlement of the British Isles" might have to be dated to the Beaker period concluding that "There is no reason why so early a date for the coming of the Celts should be impossible".[39][40] Martín Almagro Gorbea[41] proposed the origins of the Celts could be traced back to the 3rd millennium BC, seeking the initial roots in the Bell Beaker culture, thus offering the wide dispersion of the Celts throughout western Europe, as well as the variability of the different Celtic peoples, and the existence of ancestral traditions an ancient perspective. Using a multidisciplinary approach Alberto J. Lorrio and Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero reviewed and built on Almagro Gorbea's work to present a model for the origin of the Celtic archaeological groups in the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberian, Vetton, Vaccean, the Castro Culture of the northwest, Asturian-Cantabrian and Celtic of the southwest) and proposing a rethinking the meaning of "Celtic" from a European perspective.[42] More recently, John Koch[43] and Barry Cunliffe[44] have suggested that Celtic origins lie with the Atlantic Bronze Age, roughly contemporaneous with the Hallstatt culture but positioned considerably to the West, extending along the Atlantic coast of Europe.

Stephen Oppenheimer[45] points out that the only written evidence that locates the Keltoi near the source of the Danube (i.e. in the Hallstatt region) is in the Histories of Herodotus. However, Oppenheimer shows that Herodotus seemed to believe the Danube rose near the Pyrenees, which would place the Ancient Celts in a region which is more in agreement with later Classical writers and historians (i.e. in Gaul and the Iberian peninsula).

Distribution

Continental Celts

Gaul

The Romans knew the Celts then living in what became present-day France as Gauls. The territory of these peoples probably included the Low Countries, the Alps and present-day northern Italy. Julius Caesar in his Gallic Wars described the 1st-century BC descendants of those Gauls.

Eastern Gaul became the centre of the western La Tène culture. In later Iron Age Gaul, the social organisation resembled that of the Romans, with large towns. From the 3rd century BC the Gauls adopted coinage, and texts with Greek characters from southern Gaul have survived from the 2nd century BC.

Greek traders founded Massalia about 600 BC, with some objects (mostly drinking ceramics) being traded up the Rhone valley. But trade became disrupted soon after 500 BC and re-oriented over the Alps to the Po valley in the Italian peninsula. The Romans arrived in the Rhone valley in the 2nd century BC and encountered a mostly Celtic-speaking Gaul. Rome wanted land communications with its Iberian provinces and fought a major battle with the Saluvii at Entremont in 124–123 BC. Gradually Roman control extended, and the Roman Province of Gallia Transalpina developed along the Mediterranean coast.[46][47] The Romans knew the remainder of Gaul as Gallia Comata – "Hairy Gaul".

In 58 BC the Helvetii planned to migrate westward but Julius Caesar forced them back. He then became involved in fighting the various tribes in Gaul, and by 55 BC had overrun most of Gaul. In 52 BC Vercingetorix led a revolt against the Roman occupation but was defeated at the siege of Alesia and surrendered.

Following the Gallic Wars of 58–51 BC, Caesar's Celtica formed the main part of Roman Gaul, becoming the province of Gallia Lugdunensis. This territory of the Celtic tribes was bounded on the south by the Garonne and on the north by the Seine and the Marne.[48] The Romans attached large swathes of this region to neighboring provinces Belgica and Aquitania, particularly under Augustus.

Place- and personal-name analysis and inscriptions suggest that the Gaulish Celtic language was spoken over most of what is now France.[49][50]

Iberia

Until the end of the 19th century, traditional scholarship dealing with the Celts did not acknowledge their presence in the Iberian Peninsula[51][52] as a material culture relatable to the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures. However, since according to the definition of the Iron Age in the 19th century Celtic populations were supposedly rare in Iberia and did not provide a cultural scenario that could easily be linked to that of Central Europe, the presence of Celtic culture in that region was generally not fully recognised. Three divisions of the Celts of the Iberian Peninsula were assumed to have existed: the Celtiberians in the mountains near the centre of the peninsula, the Celtici in the southwest, and the Celts in the northwest (in Gallaecia and Asturias).[53]

Modern scholarship, however, has clearly proven that Celtic presence and influences were most substantial in what is today Spain and Portugal (with perhaps the highest settlement saturation in Western Europe), particularly in the central, western and northern regions.[54][55] The Celts in Iberia were divided into two main archaeological and cultural groups,[56] even though that division is not very clear:

- One group was spread out along Galicia[57] and the Iberian Atlantic shores. They were made up of the Proto / Para-Celtic Lusitanians (in Portugal)[58] and the Celtic region that Strabo called Celtica in the southwestern Iberian peninsula,[59] including the Algarve, which was inhabited by the Celtici, the Vettones and Vacceani peoples[60] (of central-western Spain and Portugal), and the Gallaecian, Astures and Cantabrian peoples of the Castro culture of northern and northwestern Spain and Portugal.[61]

- The Celtiberian group of central Spain and the upper Ebro valley.[62] This group originated when Celts (mainly Gauls and some Celtic-Germanic groups) migrated from what is now France and integrated with the local Iberian people.

The origins of the Celtiberians might provide a key to understanding the Celticisation process in the rest of the Peninsula. The process of Celticisation of the southwestern area of the peninsula by the Keltoi and of the northwestern area is, however, not a simple Celtiberian question. Recent investigations about the Callaici[63] and Bracari[64] in northwestern Portugal are providing new approaches to understanding Celtic culture (language, art and religion) in western Iberia.[65]

John T. Koch of Aberystwyth University suggested that Tartessian inscriptions of the 8th century BC might be classified as Celtic. This would mean that Tartessian is the earliest attested trace of Celtic by a margin of more than a century.[66]

Alps and Italy

The Canegrate culture (13th century BC) may represent the first migratory wave of the proto-Celtic[67] population from the northwest part of the Alps that, through the Alpine passes, had already penetrated and settled in the western Po valley between Lake Maggiore and Lake Como (Scamozzina culture). They brought a new funerary practice—cremation—which supplanted inhumation. It has also been proposed that a more ancient proto-Celtic presence can be traced back to the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (XVI-XV century BC), when North Westwern Italy appears closely linked regarding the production of bronze artifacts, including ornaments, to the western groups of the Tumulus culture.[68] (Central Europe, 1600 BC - 1200 BC).

It had been known for some time that there was an early, Celtic (Lepontic, sometimes called Cisalpine Celtic) presence in Northern Italy since inscriptions dated to the 6th century BC have been found there.

The site of Golasecca, where the Ticino exits from Lake Maggiore, was particularly suitable for long-distance exchanges, in which Golaseccans acted as intermediaries between Etruscans and the Halstatt culture of Austria, supported on the all-important trade in salt.

Ligures lived in Northern Mediterranean Coast straddling South-east French and North-west Italian coasts, including parts of Tuscany, Elba island and Corsica. Xavier Delamarre argues that Ligurian was a Celtic language, similar to, but not the same as Gaulish.[69][70] The Ligurian-Celtic question is also discussed by Barruol (1999). Ancient Ligurian is either listed as Celtic (epigraphic),[71] or Para-Celtic (onomastic).[72]

In 391 BC Gauls "who had their homes beyond the Alps streamed through the passes in great strength and seized the territory that lay between the Apennine mountains and the Alps" according to Diodorus Siculus. Polybius in the 2nd century BC wrote about co-existence of the Celts in northern Italy with Etruscan nations in the period before the Sack of Rome in 390 BC. Livy (v. 34) has the Insubres, led by Bellovesus, arrive in northern Italy during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus (7th-6th century BC), occupying the area between Milan and Cremona. Milan (Mediolanum) itself is presumably a Gaulish foundation of the early 4th century BC, its name having a Celtic etymology of "[city] in the middle of the [Padanic] plain".

Celtic La Tène and Halstatt cultures have been documented in Italy as far south as Umbria[73][74] and Latium,[75] inhabited by the Rutuli and the Umbri, closely related to the Para Celtic Ligures.[76]

At the battle of Telamon in 225 BC a large Celtic army was trapped between two Roman forces and crushed.

The defeat of the combined Samnite, Celtic and Etruscan alliance by the Romans in the Third Samnite War sounded the beginning of the end of the Celtic domination in mainland Europe, but it was not until 192 BC that the Roman armies conquered the last remaining independent Celtic kingdoms in Italy.

Eastward expansion

The Celts also expanded down the Danube river and its tributaries. One of the most influential tribes, the Scordisci, had established their capital at Singidunum in 3rd century BC, which is present-day Belgrade, Serbia. The concentration of hill-forts and cemeteries shows a density of population in the Tisza valley of modern-day Vojvodina, Serbia, Hungary and into Ukraine. Expansion into Romania was however blocked by the Dacians.

Further south, Celts settled in Thrace (Bulgaria), which they ruled for over a century, and Anatolia, where they settled as the Galatians (see also: Gallic Invasion of Greece). Despite their geographical isolation from the rest of the Celtic world, the Galatians maintained their Celtic language for at least 700 years. St Jerome, who visited Ancyra (modern-day Ankara) in 373 AD, likened their language to that of the Treveri of northern Gaul.

For Venceslas Kruta, Galatia in central Turkey was an area of dense Celtic settlement.

The Boii tribe gave their name to Bohemia, Bologna and possibly Bavaria, and Celtic artefacts and cemeteries have been discovered further east in what is now Poland and Slovakia. A Celtic coin (Biatec) from Bratislava's mint was displayed on the old Slovak 5-crown coin.

As there is no archaeological evidence for large-scale invasions in some of the other areas, one current school of thought holds that Celtic language and culture spread to those areas by contact rather than invasion.[77] However, the Celtic invasions of Italy and the expedition in Greece and western Anatolia, are well documented in Greek and Latin history.

There are records of Celtic mercenaries in Egypt serving the Ptolemies. Thousands were employed in 283–246 BC and they were also in service around 186 BC. They attempted to overthrow Ptolemy II.

Insular Celts

All Celtic languages extant today belong to the Insular Celtic languages, derived from the Celtic languages spoken in Iron Age Britain and Ireland.[78] They were separated into a Goidelic and a Brythonic branch from an early period.

Linguists have been arguing for many years whether a Celtic language came to Britain and Ireland and then split or whether there were two separate "invasions". The older view of prehistorians was that the Celtic influence in the British Isles was the result of successive invasions from the European continent by diverse Celtic-speaking peoples over the course of several centuries, accounting for the P-Celtic vs. Q-Celtic isogloss. This view has fallen into disfavour,[dubious – discuss] to be replaced by the model of a phylogenetic Insular Celtic dialect group.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, scholars commonly dated the "arrival" of Celtic culture in Britain (via an invasion model) to the 6th century BC, corresponding to archaeological evidence of Hallstatt influence and the appearance of chariot burials in what is now England. Some Iron Age migration does seem to have occurred but the nature of the interactions with the indigenous populations of the isles is unknown. In the late Iron Age. According to this model, by about the 6th century (Sub-Roman Britain), most of the inhabitants of the Isles were speaking Celtic languages of either the Goidelic or the Brythonic branch. Since the late 20th century, a new model has emerged (championed by archaeologists such as Barry Cunliffe and Celtic historians such as John T. Koch) which places the emergence of Celtic culture in Britain much earlier, in the Bronze Age, and credits its spread not to invasion, but due to a gradual emergence in situ out of Proto-Indo-European culture (perhaps introduced to the region by the Bell Beaker People, and enabled by an extensive network of contacts that existed between the peoples of Britain and Ireland and those of the Atlantic seaboard.[79][80]

It should be noted, however, that Classical writers did not apply the terms Κελτοί or "Celtae" to the inhabitants of Britain or Ireland,[1][2][3] leading a number of scholars to question the use of the term Celt to describe the Iron Age inhabitants of those islands.[1][2][3][4] The first historical account of the islands of Britain and Ireland was by Pytheas, a Greek from the city of Massalia, who around 310-306 BC, sailed around what he called the "Pretannikai nesoi", which can be translated as the "Pretannic Isles".[81] In general, classical writers referred to the inhabitants of Britain as Pretannoi or Britanni.[82] Strabo, writing in the Roman era, clearly distinguished between the Celts and Britons.[83]

Romanisation

Under Caesar the Romans conquered Celtic Gaul, and from Claudius onward the Roman empire absorbed parts of Britain. Roman local government of these regions closely mirrored pre-Roman tribal boundaries, and archaeological finds suggest native involvement in local government.

The native peoples under Roman rule became Romanised and keen to adopt Roman ways. Celtic art had already incorporated classical influences, and surviving Gallo-Roman pieces interpret classical subjects or keep faith with old traditions despite a Roman overlay.

The Roman occupation of Gaul, and to a lesser extent of Britain, led to Roman-Celtic syncretism. In the case of the continental Celts, this eventually resulted in a language shift to Vulgar Latin, while the Insular Celts retained their language.

There was also considerable cultural influence exerted by Gaul on Rome, particularly in military matters and horsemanship, as the Gauls often served in the Roman cavalry. The Romans adopted the Celtic cavalry sword, the spatha, and Epona, the Celtic horse goddess.[84][85]

Society

To the extent that sources are available, they depict a pre-Christian Iron Age Celtic social structure based formally on class and kingship, although this may only have been a particular late phase of organization in Celtic societies. Patron-client relationships similar to those of Roman society are also described by Caesar and others in the Gaul of the 1st century BC.

In the main, the evidence is of tribes being led by kings, although some argue that there is also evidence of oligarchical republican forms of government eventually emerging in areas which had close contact with Rome. Most descriptions of Celtic societies portray them as being divided into three groups: a warrior aristocracy; an intellectual class including professions such as druid, poet, and jurist; and everyone else. In historical times, the offices of high and low kings in Ireland and Scotland were filled by election under the system of tanistry, which eventually came into conflict with the feudal principle of primogeniture in which succession goes to the first-born son.

Little is known of family structure among the Celts. Patterns of settlement varied from decentralised to urban. The popular stereotype of non-urbanised societies settled in hillforts and duns,[86] drawn from Britain and Ireland (there are about 3,000 hill forts known in Britain)[87] contrasts with the urban settlements present in the core Hallstatt and La Tène areas, with the many significant oppida of Gaul late in the first millennium BC, and with the towns of Gallia Cisalpina.

Slavery, as practised by the Celts, was very likely similar to the better documented practice in ancient Greece and Rome.[88] Slaves were acquired from war, raids, and penal and debt servitude.[88] Slavery was hereditary[citation needed], though manumission was possible. The Old Irish word for slave, cacht, and the Welsh term caeth are likely derived from the Latin captus, captive, suggesting that slave trade was an early venue of contact between Latin and Celtic societies.[88] In the Middle Ages, slavery was especially prevalent in the Celtic countries.[89] Manumissions were discouraged by law and the word for "female slave", cumal, was used as a general unit of value in Ireland.[90]

Archaeological evidence suggests that the pre-Roman Celtic societies were linked to the network of overland trade routes that spanned Eurasia. Archaeologists have discovered large prehistoric trackways crossing bogs in Ireland and Germany. Due to their substantial nature, these are believed to have been created for wheeled transport as part of an extensive roadway system that facilitated trade.[91] The territory held by the Celts contained tin, lead, iron, silver and gold.[92] Celtic smiths and metalworkers created weapons and jewellery for international trade, particularly with the Romans.

The myth that the Celtic monetary system consisted of wholly barter is a common one, but is in part false. The monetary system was complex and is still not understood (much like the late Roman coinages), and due to the absence of large numbers of coin items, it is assumed that "proto-money" was used. This included bronze items made from the early La Tène period and onwards, which were often in the shape of axeheads, rings, or bells. Due to the large number of these present in some burials, it is thought they had a relatively high monetary value, and could be used for "day to day" purchases. Low-value coinages of potin, a bronze alloy with high tin content, were minted in most Celtic areas of the continent and in South-East Britain prior to the Roman conquest of these lands. Higher-value coinages, suitable for use in trade, were minted in gold, silver, and high-quality bronze. Gold coinage was much more common than silver coinage, despite being worth substantially more, as while there were around 100 mines in Southern Britain and Central France, silver was more rarely mined. This was due partly to the relative sparcity of mines and the amount of effort needed for extraction compared to the profit gained. As the Roman civilisation grew in importance and expanded its trade with the Celtic world, silver and bronze coinage became more common. This coincided with a major increase in gold production in Celtic areas to meet the Roman demand, due to the high value Romans put on the metal. The large number of gold mines in France is thought to be a major reason why Caesar invaded.

There are only very limited records from pre-Christian times written in Celtic languages. These are mostly inscriptions in the Roman and sometimes Greek alphabets. The Ogham script, an Early Medieval alphabet, was mostly used in early Christian times in Ireland and Scotland (but also in Wales and England), and was only used for ceremonial purposes such as inscriptions on gravestones. The available evidence is of a strong oral tradition, such as that preserved by bards in Ireland, and eventually recorded by monasteries. Celtic art also produced a great deal of intricate and beautiful metalwork, examples of which have been preserved by their distinctive burial rites.

In some regards the Atlantic Celts were conservative: for example, they still used chariots in combat long after they had been reduced to ceremonial roles by the Greeks and Romans. However, despite being outdated, Celtic chariot tactics were able to repel the invasion of Britain attempted by Julius Caesar.

According to Diodorus Siculus:

The Gauls are tall of body with rippling muscles and white of skin and their hair is blond, and not only naturally so for they also make it their practice by artificial means to increase the distinguishing colour which nature has given it. For they are always washing their hair in limewater and they pull it back from the forehead to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance is like that of Satyrs and Pans since the treatment of their hair makes it so heavy and coarse that it differs in no respect from the mane of horses. Some of them shave the beard but others let it grow a little; and the nobles shave their cheeks but they let the moustache grow until it covers the mouth.

Clothing

During the later Iron Age the Gauls generally wore long-sleeved shirts or tunics and long trousers (called braccae by the Romans).[93] Clothes were made of wool or linen, with some silk being used by the rich. Cloaks were worn in the winter. Brooches and armlets were used, but the most famous item of jewellery was the torc, a neck collar of metal, sometimes gold. The horned Waterloo Helmet in the British Museum, which long set the standard for modern images of Celtic warriors, is in fact a unique survival, and may have been a piece for ceremonial rather than military wear.

Gender and sexual norms

According to Aristotle, most "belligerent nations" were strongly influenced by their women, but the Celts were unusual because their men openly preferred male lovers (Politics II 1269b).[94] H. D. Rankin in Celts and the Classical World notes that "Athenaeus echoes this comment (603a) and so does Ammianus (30.9). It seems to be the general opinion of antiquity."[95] In book XIII of his Deipnosophists, the Roman Greek rhetorician and grammarian Athenaeus, repeating assertions made by Diodorus Siculus in the 1st century BC (Bibliotheca historica 5:32), wrote that Celtic women were beautiful but that the men preferred to sleep together. Diodorus went further, stating that "the young men will offer themselves to strangers and are insulted if the offer is refused". Rankin argues that the ultimate source of these assertions is likely to be Poseidonius and speculates that these authors may be recording male "bonding rituals".[96]

The sexual freedom of women in Britain was noted by Cassius Dio:

... a very witty remark is reported to have been made by the wife of Argentocoxus, a Caledonian, to Julia Augusta. When the empress was jesting with her, after the treaty, about the free intercourse of her sex with men in Britain, she replied: "We fulfill the demands of nature in a much better way than do you Roman women; for we consort openly with the best men, whereas you let yourselves be debauched in secret by the vilest." Such was the retort of the British woman.[97]

There are instances recorded where women participated both in warfare and in kingship, although they were in the minority in these areas. Plutarch reports that Celtic women acted as ambassadors to avoid a war among Celts chiefdoms in the Po valley during the 4th century BC.[98]

Very few reliable sources exist regarding Celtic views towards gender divisions and societal status, though some archaeological evidence does suggest that their views towards gender roles may differ from contemporary and less egalitarian classical counterparts of the Roman era.[99][100]

There are some general indications from Iron Age burial sites in the Champagne and Bourgogne regions of Northeastern France suggesting that women may have had roles in combat during the earlier La Tène period. However, the evidence is far from conclusive.[101] Examples of individuals buried with both female jewellery and weaponry have been identified, such as the Vix Grave, and there are questions about the gender of some skeletons that were buried with warrior assemblages. However, it has been suggested that "the weapons may indicate rank instead of masculinity".[102]

Among the insular Celts, there is a greater amount of historic documentation to suggest warrior roles for women. In addition to commentary by Tacitus about Boudica, there are indications from later period histories that also suggest a more substantial role for "women as warriors", in symbolic if not actual roles. Posidonius and Strabo described an island of women where men could not venture for fear of death, and where the women ripped each other apart.[103] Other writers, such as Ammianus Marcellinus and Tacitus, mentioned Celtic women inciting, participating in, and leading battles.[104] Poseidonius' anthropological comments on the Celts had common themes, primarily primitivism, extreme ferocity, cruel sacrificial practices, and the strength and courage of their women.[105]

Under Brehon Law, which was written down in early Medieval Ireland after conversion to Christianity, a woman had the right to divorce her husband and gain his property if he was unable to perform his marital duties due to impotence, obesity, homosexual inclination or preference for other women.[106]

Celtic art

Celtic art is generally used by art historians to refer to art of the La Tène period across Europe, while the Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, that is what "Celtic art" evokes for much of the general public, is called Insular art in art history. Both styles absorbed considerable influences from non-Celtic sources, but retained a preference for geometrical decoration over figurative subjects, which are often extremely stylised when they do appear; narrative scenes only appear under outside influence. Energetic circular forms, triskeles and spirals are characteristic. Much of the surviving material is in precious metal, which no doubt gives a very unrepresentative picture, but apart from Pictish stones and the Insular high crosses, large monumental sculpture, even with decorative carving, is very rare; possibly it was originally common in wood.

The interlace patterns that are often regarded as typical of "Celtic art" were in fact introduced to Insular art from the animal Style II of Germanic Migration Period art, though taken up with great skill and enthusiasm by Celtic artists in metalwork and illuminated manuscripts. Equally, the forms used for the finest Insular art were all adopted from the Roman world: Gospel books like the Book of Kells and Book of Lindisfarne, chalices like the Ardagh Chalice and Derrynaflan Chalice, and penannular brooches like the Tara Brooch. These works are from the period of peak achievement of Insular art, which lasted from the 7th to the 9th centuries, before the Viking attacks sharply set back cultural life.

In contrast the less well known but often spectacular art of the richest earlier Continental Celts, before they were conquered by the Romans, often adopted elements of Roman, Greek and other "foreign" styles (and possibly used imported craftsmen) to decorate objects that were distinctively Celtic. After the Roman conquests, some Celtic elements remained in popular art, especially Ancient Roman pottery, of which Gaul was actually the largest producer, mostly in Italian styles, but also producing work in local taste, including figurines of deities and wares painted with animals and other subjects in highly formalised styles. Roman Britain also took more interest in enamel than most of the Empire, and its development of champlevé technique was probably important to the later Medieval art of the whole of Europe, of which the energy and freedom of Insular decoration was an important element. Rising nationalism brought Celtic revivals from the 19th century.

Warfare and weapons

Tribal warfare appears to have been a regular feature of Celtic societies. While epic literature depicts this as more of a sport focused on raids and hunting rather than organised territorial conquest, the historical record is more of tribes using warfare to exert political control and harass rivals, for economic advantage, and in some instances to conquer territory.[citation needed]

The Celts were described by classical writers such as Strabo, Livy, Pausanias, and Florus as fighting like "wild beasts", and as hordes. Dionysius said that their "manner of fighting, being in large measure that of wild beasts and frenzied, was an erratic procedure, quite lacking in military science. Thus, at one moment they would raise their swords aloft and smite after the manner of wild boars, throwing the whole weight of their bodies into the blow like hewers of wood or men digging with mattocks, and again they would deliver crosswise blows aimed at no target, as if they intended to cut to pieces the entire bodies of their adversaries, protective armour and all".[107] Such descriptions have been challenged by contemporary historians.[108]

Polybius (2.33) indicates that the principal Celtic weapon was a long bladed sword which was used for hacking edgewise rather than stabbing. Celtic warriors are described by Polybius and Plutarch as frequently having to cease fighting in order to straighten their sword blades. This claim has been questioned by some archaeologists, who note that Noric steel, steel produced in Celtic Noricum, was famous in the Roman Empire period and was used to equip the Roman military.[109][110] However, Radomir Pleiner, in The Celtic Sword (1993) argues that "the metallographic evidence shows that Polybius was right up to a point", as around one third of surviving swords from the period might well have behaved as he describes.[111]

Polybius also asserts that certain of the Celts fought naked, "The appearance of these naked warriors was a terrifying spectacle, for they were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life."[112] According to Livy this was also true of the Celts of Asia Minor.[113]

Head hunting

Celts had a reputation as head hunters. According to Paul Jacobsthal, "Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world."[114] Arguments for a Celtic cult of the severed head include the many sculptured representations of severed heads in La Tène carvings, and the surviving Celtic mythology, which is full of stories of the severed heads of heroes and the saints who carry their own severed heads, right down to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where the Green Knight picks up his own severed head after Gawain has struck it off, just as St. Denis carried his head to the top of Montmartre.

A further example of this regeneration after beheading lies in the tales of Connemara's St. Feichin, who after being beheaded by Viking pirates carried his head to the Holy Well on Omey Island and on dipping the head into the well placed it back upon his neck and was restored to full health.

Diodorus Siculus, in his 1st-century History had this to say about Celtic head-hunting:

They cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The blood-stained spoils they hand over to their attendants and striking up a paean and singing a song of victory; and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses, just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm in cedar oil the heads of the most distinguished enemies, and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that for this head one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a large sum of money. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold

In Gods and Fighting Men, Lady Gregory's Celtic Revival translation of Irish mythology, heads of men killed in battle are described in the beginning of the story The Fight with the Fir Bolgs as pleasing to Macha, one aspect of the war goddess Morrigu.

Religion

Polytheism

Like other European Iron Age tribal societies, the Celts practised a polytheistic religion.[115] Many Celtic gods are known from texts and inscriptions from the Roman period. Rites and sacrifices were carried out by priests known as druids. The Celts did not see their gods as having human shapes until late in the Iron Age. Celtic shrines were situated in remote areas such as hilltops, groves, and lakes.

Celtic religious patterns were regionally variable; however, some patterns of deity forms, and ways of worshipping these deities, appeared over a wide geographical and temporal range. The Celts worshipped both gods and goddesses. In general, Celtic gods were deities of particular skills, such as the many-skilled Lugh and Dagda, while goddesses were associated with natural features, particularly rivers (such as Boann, goddess of the River Boyne). This was not universal, however, as goddesses such as Brighid and The Morrígan were associated with both natural features (holy wells and the River Unius) and skills such as blacksmithing and healing.[116]

Triplicity is a common theme in Celtic cosmology, and a number of deities were seen as threefold.[117] This trait is exhibited by The Three Mothers, a group of goddesses worshipped by many Celtic tribes (with regional variations).[118]

The Celts had literally hundreds of deities, some of which were unknown outside a single family or tribe, while others were popular enough to have a following that crossed lingual and cultural barriers. For instance, the Irish god Lugh, associated with storms, lightning, and culture, is seen in similar forms as Lugos in Gaul and Lleu in Wales. Similar patterns are also seen with the continental Celtic horse goddess Epona and what may well be her Irish and Welsh counterparts, Macha and Rhiannon, respectively.[119]

Roman reports of the druids mention ceremonies being held in sacred groves. La Tène Celts built temples of varying size and shape, though they also maintained shrines at sacred trees and votive pools.[115]

Druids fulfilled a variety of roles in Celtic religion, serving as priests and religious officiants, but also as judges, sacrificers, teachers, and lore-keepers. Druids organised and ran religious ceremonies, and they memorised and taught the calendar. Other classes of druids performed ceremonial sacrifices of crops and animals for the perceived benefit of the community.[120]

Gallic calendar

The Coligny calendar, which was found in 1897 in Coligny, Ain, was engraved on a bronze tablet, preserved in 73 fragments, that originally was 1.48 m wide and 0.9 m high (Lambert p. 111). Based on the style of lettering and the accompanying objects, it probably dates to the end of the 2nd century.[121] It is written in Latin inscriptional capitals, and is in the Gallic language. The restored tablet contains 16 vertical columns, with 62 months distributed over 5 years.

The French archaeologist J. Monard speculated that it was recorded by druids wishing to preserve their tradition of timekeeping in a time when the Julian calendar was imposed throughout the Roman Empire. However, the general form of the calendar suggests the public peg calendars (or parapegmata) found throughout the Greek and Roman world.[122]

Roman influence

The Roman invasion of Gaul brought a great deal of Celtic peoples into the Roman Empire. Roman culture had a profound effect on the Celtic tribes which came under the empire's control. Roman influence led to many changes in Celtic religion, the most noticeable of which was the weakening of the druid class, especially religiously; the druids were to eventually disappear altogether. Romano-Celtic deities also began to appear: these deities often had both Roman and Celtic attributes and combined the names of Roman and Celtic deities. Other changes included the adaptation of the Jupiter Pole, a sacred pole which was used throughout Celtic regions of the empire, primarily in the north. Another major change in religious practice was the use of stone monuments to represent gods and goddesses. The Celts had only created wooden idols (including monuments carved into trees, which were known as sacred poles) previously to Roman conquest.[118]

Celtic Christianity

While the regions under Roman rule adopted Christianity along with the rest of the Roman empire, unconquered areas of Ireland and Scotland began to move from Celtic polytheism to Christianity in the 5th century. Ireland was converted by missionaries from Britain, such as Saint Patrick. Later missionaries from Ireland were a major source of missionary work in Scotland, Anglo-Saxon parts of Britain, and central Europe (see Hiberno-Scottish mission). Celtic Christianity, the forms of Christianity that took hold in Britain and Ireland at this time, had for some centuries only limited and intermittent contact with Rome and continental Christianity, as well as some contacts with Coptic Christianity. Some elements of Celtic Christianity developed, or retained, features that made them distinct from the rest of Western Christianity, most famously their conservative method of calculating the date of Easter. In 664 the Synod of Whitby began to resolve these differences, mostly by adopting the current Roman practices, which the Gregorian Mission from Rome had introduced to Anglo-Saxon England.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Koch, John (2005). Celtic Culture: a historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. xx. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f James, Simon (1999). The Atlantic Celts – Ancient People Or Modern Invention. University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ a b c d e Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2913-2.

- ^ a b c Pryor, Francis (2004). Britain BC. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0007126934.

- ^ a b c d Chadwick, Nora; Corcoran, J. X. W. P. (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 28–33.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (1997). The Ancient Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 39–67.

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic – see map 9.3 The Ancient Celtic Languages c. 440/430 BC – see third map in PDF at URL provided which is essentially the same map (PDF). Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 193. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic – see map 9.2 Celtic expansion from Hallstatt/La Tene central Europe – see second map in PDF at URL provided which is essentially the same map (PDF). Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 190. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Stifter, David (2008). Old Celtic Languages (PDF). pp. 24–37.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts – a very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- ^ McKevitt, Kerry Ann (2006). "Mythologizing Identity and History: a look at the Celtic past of Galicia" (PDF). E-Keltoi. 6: 651–673. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sarunas Milisauskas, European prehistory: a survey. Springer, 2002 ISBN 0-306-47257-0. 2002. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-306-47257-2. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ H. D. Rankin, Celts and the classical world. Routledge, 1998 ISBN 0-415-15090-6. 1998. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-415-15090-3. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Julius Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico 1.1: “All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae live, another in which the Aquitani live, and the third are those who in their own tongue are called Celtae, in our language Galli.”

- ^ Strabo, Geography, Book 4.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, The Natural History 21: “the Mirobrigenses, surnamed Celtici” (“Mirobrigenses qui Celtici cognominantur”).

- ^ http://revistas.ucm.es/est/11326875/articulos/HIEP0101110006A.PDF

- ^ Fernando DE ALMEIDA, Breve noticia sobre o santuário campestre romano de Miróbriga dos Celticos (Portugal) :D(IS) M(ANIBUS) S(ACRUM) / C(AIUS) PORCIUS SEVE/RUS MIROBRIGEN(SIS) / CELT(ICUS) ANN(ORUM) LX / H(IC) S(ITUS) E(ST) S(IT) T(IBI) T(ERRA) L(EVIS)

- ^ Karl, Raimund (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 2: The Celts from everywhere and nowhere: a re-evaluation of the origins of the Celts and the emergence of Celtic cultures. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 39–64. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 794–795. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ Spencer and Zwicky, Andrew and Arnold M (1998). The handbook of morphology. Blackwell Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 0-631-18544-5.

- ^ (Lhuyd, p. 290) Lhuyd, E. Archaeologia Britannica; An account of the languages, histories, and customs of the original inhabitants of Great Britain. (reprint ed.) Irish University Press, 1971. ISBN 0-7165-0031-0

- ^ Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 532. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ Mountain, Harry (1998). The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume 1. uPublish.com. p. 252. ISBN 1-58112-889-4.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas; et al. (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. pp. 95–102.

- ^ Paul Graves-Brown, Siân Jones, Clive Gamble, Cultural identity and archaeology: the construction of European communities, pp 242–244. Routledge, 1996 ISBN 0-415-10676-1. 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-10676-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Carl McColman, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom, pp 31–34. Alpha Books, 2003, ISBN 0-02-864417-4. 6 May 2003. ISBN 978-0-02-864417-2. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Monaghan, Patricia (2008). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Facts on File Inc. ISBN 978-0-8160-7556-0.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts with an introductory chapter by J.X.W.P.Corcoran. Penguin Books. p. 81.

- ^ e.g. Patrick Sims-Williams, Ancient Celtic Placenames in Europe and Asia Minor, Publications of the Philological Society, No. 39 (2006); Bethany Fox, 'The P-Celtic Place-Names of North-East England and South-East Scotland', The Heroic Age, 10 (2007), http://www.heroicage.org/issues/10/fox.html (also available at http://www.alarichall.org.uk/placenames/fox.htm). See also List of Celtic place names in Portugal.

- ^ Murray, Tim (April 2007). pg346. ISBN 978-1-57607-186-1. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (2008). pg 48. ISBN 978-1-4051-2597-0. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ F. Fleming, Heroes of the Dawn: Celtic Myth, 1996. p. 9 & 134.

- ^ Harding, Dennis William (2007). pg5. ISBN 978-0-415-35177-5. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ pg 386. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ [1] The Celts in Iberia: An Overview – Alberto J. Lorrio (Universidad de Alicante) & Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) – Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Volume 6: 167–254 The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula, 1 February 2005

- ^ Villar, Francisco. The Indo-Europeans and the origins of Europe – Italian version p.446

- ^ *Otto Hermann Frey, "A new approach to early Celtic art". Setting the Glauberg finds in context of shifting iconography, Royal Irish Academy (2004)

- ^ Myles Dillon and Nora Kershaw Chadwick, The Celtic Realms, 1967, 18–19

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 1: Celticization from the West – The Contribution of Archaeology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- ^ 2001 p 95. La lengua de los Celtas y otros pueblos indoeuropeos de la península ibérica. In Almagro-Gorbea, M., Mariné, M. and Álvarez-Sanchís, J.R. (eds) Celtas y Vettones, pp. 115–121. Ávila: Diputación Provincial de Ávila.

- ^ Lorrio and Ruiz Zapatero, Alberto J. and Gonzalo (2005). "The Celts in Iberia: An Overview". e-Keltoi. 6 : The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula: 167–254.

- ^ Koch, John (2009). Tartessian: Celtic from the Southwest at the Dawn of History in Acta Palaeohispanica X Palaeohispanica 9 (2009) (PDF). Palaeohispanica. pp. 339–351. ISSN 1578-5386. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Race Apart: Insularity and Connectivity in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 75, 2009, pp. 55–64. The Prehistoric Society. p. 61.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen (2007). The Origins of the British, pp. 21–56. Robinson.

- ^ Dietler, Michael (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-26551-3.

- ^ Dietler, Michael (2005). Consumption and Colonial Encounters in the Rhône Basin of France: A Study of Early Iron Age Political Economy. Monographies d'Archéologie Meditérranéenne, 21, CNRS, France. ISBN 978-2-912369-10-9.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts. Oxford Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts. Oxford Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- ^ Dietler, Michael (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. University of California Press. pp. 75–94. ISBN 0-520-26551-3.

- ^ Chambers, William; Chambers, Robert (1842). Chambers's information for the people pg50. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Brownson, Orestes Augustus (1859). Brownson's Quarterly Review pg505. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Prichard, James Cowles (1841). Researches into the Physical History of Mankind. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Quintela, Marco V. García (2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times". Center for Celtic Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Pedreño, Juan Carlos Olivares (2005). "Celtic Gods of the Iberian Peninsula". Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Alberto J. Lorrio, Gonzalo Ruiz Zapatero (2005). "The Celts in Iberia: An Overview". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 167–254.

- ^ Alberro, Manuel (2005). "Celtic Legacy in Galicia". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 1005–1035.

- ^ Júdice Gamito, Teresa (2005). "The Celts in Portugal". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 571–606.

- ^ Berrocal-Rangel, Luis (2005). "The Celts of the Southwestern Iberian Peninsula". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 481–96.

- ^ R. Álvarez-Sanchís, Jesús (2005). "Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 255–286.

- ^ V. García Quintela, Marco (2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 497–570.

- ^ Burillo Mozota, Francisco (2005). "Celtiberians: Problems and Debates". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 411–480.

- ^ R. Luján Martínez, Eugenio (2005). "The Language(s) of the Callaeci". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6: 715–748.

- ^ Coutinhas, José Manuel (2006), Aproximação à identidade etno-cultural dos Callaici Bracari, Porto.

- ^ Archeological site of Tavira, official website

- ^ John T. Koch, Tartessian: Celtic From the South-west at the Dawn of History, Celtic Studies Publications, (2009)

- ^ Venceslas Kruta: La grande storia dei celti. La nascita, l'affermazione e la decadenza, Newton & Compton, 2003, ISBN 88-8289-851-2, ISBN 978-88-8289-851-9

- ^ "The Golasecca civilization is therefore the expression of the oldest [ [ Celts ] ] of Italy and included several groups that had the name of Insubres, Laevi, Lepontii, Oromobii (o Orumbovii)". (Raffaele C. De Marinis)

- ^ http://www.celtnet.org.uk/gods_v/vasio.html

- ^ http://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=Ligurian%20language%20(ancient)

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 54.

- ^ Kruta, Venceslas (1991). The Celts. Thames and Hudson. p. 55.

- ^ Prichard, Researches Into the Physical History of Mankind: In Two Volumes, Volume 2, p. 60

- ^ Raymond F. McNair, KEY TO NORTHWEST EUROPEAN ORIGINS, p. 81

- ^ Hazlit, William. The Classical Gazetteer (1851), p. 297.

- ^ Nicholas Hammond, Howard Scullard.Dizionario di antichità classiche. Milano, Edizioni San Paolo, 1995, p.1836-1836. ISBN 88-215-3024-8.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2003). The Celts: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford. p. 71. ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- ^ Ball, Martin, Muller, Nicole (eds.) The Celtic Languages, Routledge, 2003, p. 67ff.

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry, Koch, John T. (eds.), Celtic from the West, David Brown Co., 2012

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry, Facing the Ocean, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 125. ISBN 0-7524-2913-2.

- ^ Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 0-7524-2913-2.

- ^ Collis, John (2003). The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 0-7524-2913-2.

- ^ Tristram, Hildegard L. C. (2007). The Celtic languages in contact. Potsdam University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-940793-07-2.

- ^ Ní Dhoireann, Kym. "The Horse Amongst the Celts".

- ^ "The Iron Age[dead link]". Smr.herefordshire.gov.uk.

- ^ "The Landscape of Britain". Michael Reed (1997). CRC Press. p.56. ISBN 0-203-44411-6

- ^ a b c Simmons, Victoria (2006). John T. Koch (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO. p. 1615. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- ^ Simmons, op.cit., citing Wendy Davies, Wales in the Early Middle Ages, 64.

- ^ Simmons, op.cit., at 1616, citing Kelly, Guide to Early Irish Law, 96.

- ^ Casparie, Wil A.; Moloney, Aonghus (January 1994). "Neolithic wooden trackways and bog hydrology". Journal of Paleolimnology. 12. Springer Netherlands: 49–64. doi:10.1007/BF00677989.

- ^ Template:PDFlink Beatrice Cauuet (Université Toulouse Le Mirail, UTAH, France)

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica

- ^ Percy, William A. (1996). Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. University of Illinois Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-252-06740-1. Retrieved 18 September 2009.; Rankin, H.D. Celts and the Classical World, p.55

- ^ Rankin, p. 55

- ^ Rankin, p.78

- ^ Roman History Volume IX Books 71–80, Dio Cassiuss and Earnest Carry translator (1927), Loeb Classical Library ISBN 0-674-99196-6.

- ^ Ellis, Peter Berresford (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- ^ J.A. MacCulloch (1911). The Religion of the Ancient Celts. MORRISON & GIBB LIMITED. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Evans, Thomas L. (2004). Quantified Identities: A Statistical Summary and Analysis of Iron Age Cemeteries in North-Eastern France 600 – 130 BC, BAR International Series 1226. Archaeopress. pp. 34–40, 158–188.

- ^ Evans, Thomas L. (2004). Quantified Identities: A Statistical Summary and Analysis of Iron Age Cemeteries in North-Eastern France 600 – 130 BC, BAR International Series 1226. Archaeopress. pp. 34–37.

- ^ Nelson, Sarah M. (2004). Gender in archaeology: analyzing power and prestige: Volume 9 of Gender and archaeology series. Rowman Altamira. p. 119.

- ^ Bitel, Lisa M. (1996). Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland. Cornell University Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-8014-8544-4.

- ^ Tierney, J. J. (1960). The Celtic Ethnography of Posidonius, PRIA 60 C. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. pp. 1.89–275.

- ^ Rankin, David (1996). Celts and the Classical World. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 0-415-15090-6.

- ^ University College, Cork. Cáin Lánamna (Couples Law) . 2005.[2] Access date: 7 March 2006.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities p259 Excerpts from Book XIV

- ^ Ellis, Peter Berresford (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 60–3. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- ^ "Noricus ensis," Horace, Odes, i. 16.9

- ^ Vagn Fabritius Buchwald, Iron and steel in ancient times, 2005, p.127

- ^ Radomir Pleiner, in The Celtic Sword, Oxford: Clarendon Press (1993), p.159.

- ^ Polybius, Histories II.28

- ^ Livy, History XXII.46 and XXXVIII.21

- ^ Paul Jacobsthal Early Celtic Art

- ^ a b Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) The Ancient Celts. Oxford, Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-815010-5, pp.202, 204–8. p. 183 (religion)

- ^ Sjoestedt, Marie-Louise (originally published in French, 1940, reissued 1982) Gods and Heroes of the Celts. Translated by Myles Dillon, Berkeley, CA, Turtle Island Foundation ISBN 0-913666-52-1, pp. 24–46.

- ^ Sjoestedt (1940) pp.16, 24–46.

- ^ a b Inse Jones, Prudence, and Nigel Pennick. History of pagan Europe. London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

- ^ Sjoestedt (1940) pp.xiv-xvi, 14–46.

- ^ Sjoestedt (1982) pp. xxvi–xix.

- ^ Lambert, Pierre-Yves (2003). La langue gauloise. Paris, Editions Errance. 2nd edition. ISBN 2-87772-224-4. Chapter 9 is titled "Un calandrier gaulois"

- ^ Lehoux, D. R. Parapegmata: or Astrology, Weather, and Calendars in the Ancient World, pp 63–5. PhD Dissertation, University of Toronto, 2000.

Bibliography

- Alberro, Manuel and Arnold, Bettina (eds.), e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Volume 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, Center for Celtic Studies, 2005.

- Collis, John. The Celts: Origins, Myths and Inventions. Stroud: Tempus Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0-7524-2913-2. Historiography of Celtic studies.

- Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-19-815010-5.

- Cunliffe, Barry. Iron Age Britain. London: Batsford, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8839-5

- Cunliffe, Barry. The Celts: A Very Short Introduction. 2003

- Freeman, Philip Mitchell The Earliest Classical Sources on the Celts: A Linguistic and Historical Study. Diss. Harvard University, 1994. (link)

- Gamito, Teresa J. The Celts in Portugal. In E-Keltoi, Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, vol. 6. 2005.

- Haywood, John. Historical Atlas of the Celtic World. 2001.

- Herm, Gerhard. The Celts: The People who Came out of the Darkness. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1977.

- James, Simon. Exploring the World of the Celts 1993.

- James, Simon. The Atlantic Celts – Ancient People Or Modern Invention? Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, August 1999. ISBN 0-299-16674-0.

- James, Simon & Rigby, Valerie. Britain and the Celtic Iron Age. London: British Museum Press, 1997. ISBN 0-7141-2306-4.

- Kruta, V., O. Frey, Barry Raftery and M. Szabo. eds. The Celts. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1991. ISBN 0-8478-2193-5. A translation of Les Celtes: Histoire et Dictionnaire 2000.

- Laing, Lloyd. The Archaeology of Late Celtic Britain and Ireland c. 400–1200 AD. London: Methuen, 1975. ISBN 0-416-82360-2

- Laing, Lloyd and Jenifer Laing. Art of the Celts, London: Thames and Hudson, 1992 ISBN 0-500-20256-7

- MacKillop, James. A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-280120-1

- Maier, Bernhard: Celts: A History from Earliest Times to the Present. University of Notre Dame Press 2003. ISBN 978-0-268-02361-4

- McEvedy, Colin. The Penguin Atlas of Ancient History. New York: Penguin, 1985. ISBN 0-14-070832-4

- Mallory, J. P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- O'Rahilly, T. F. Early Irish History Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1946.

- Powell, T. G. E. The Celts. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1980. third ed. 1997. ISBN 0-500-27275-1.

- Raftery, Barry. Pagan Celtic Ireland: The Enigma of the Irish Iron Age. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994. ISBN 0-500-27983-7.

External links

- Ancient Celtic music – in the Citizendium

- Essays on Celtiberian topics – in e-Keltoi, University of Wisconsin, Madison

- Ancient Celtic Warriors in History

- Celts descended from Spanish fishermen, study finds

- Discussion – with academician Barry Cunliffe, on BBC Radio 4's In Our Time, 21 February 2002. (Streaming RealPlayer format)

Geography

- An interactive map showing the lands of the Celts between 800 BC and 305 AD.

- Detailed map of the Pre-Roman Peoples of Iberia (around 200 BC), showing the Celtic territories

- Map of Celtic lands

Organisations