Harry Potter

The Harry Potter logo first used for the American edition of the novel series (and some other editions worldwide), and then the film series. | |

| |

| Author | J. K. Rowling |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy, Drama, Young-adult fiction, Mystery, Thriller, Bildungsroman |

| Publisher | Bloomsbury Publishing (UK) Arthur A. Levine Books (US) Little, Brown (UK) |

| Published | 26 June 1997 – 21 July 2007, 31 July 2016[1] (initial publication) |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) Audiobook E-book (as of March 2012[update])[2] |

| No. of books | 7 |

| Website | www |

Harry Potter is a series of seven novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the life of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. The main story arc concerns Harry's struggle against Lord Voldemort, the Dark wizard who intends to become immortal, overthrow the Ministry of Magic, subjugate non-magic people and destroy anyone who stands in his way.

Since the release of the first novel, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, on 30 June 1997, the books have gained immense popularity, critical acclaim and commercial success worldwide. They attracted a wide adult audience, and have remained one of the preeminent cornerstones of young adult literature.[3] The series has also had some share of criticism, including concern about the increasingly dark tone as the series progressed, as well as the often gruesome and graphic violence depicted in the series. As of July 2013[update], the books have sold more than 450 million copies worldwide, making the series the best-selling book series in history, and have been translated into seventy-three languages.[4][5] The last four books consecutively set records as the fastest-selling books in history, with the final instalment selling roughly eleven million copies in the United States within twenty four hours of its release.

A series of many genres, including fantasy, drama, coming of age and the British school story (which includes elements of mystery, thriller, adventure, horror and romance), it has many cultural meanings and references.[6] According to Rowling, the main theme is death.[7] There are also many other themes in the series, such as prejudice, corruption, and madness.[8]

The series was originally published in English by two major publishers, Bloomsbury in the United Kingdom and Scholastic Press in the United States. The play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child will open in London on 30 July 2016 at the Palace Theatre and its script will be published by Little, Brown in the United Kingdom on 31 July 2016, who also published Rowling's adult novels and those written under her pen name Robert Galbraith.[9] The seven books were adapted into an eight-part film series by Warner Bros. Pictures, which is the second highest-grossing film series of all time as of August 2015[update]. The series also originated much tie-in merchandise, making the Harry Potter brand worth in excess of $15 billion.[10]

Because of the success of the books and films, Harry Potter-themed areas, known as The Wizarding World of Harry Potter, have been created at several Universal Parks & Resorts theme parks around the world. The franchise continues to expand, with numerous supplemental books to accompany the films and the original novels, a studio tour in London that opened in 2012, a travelling exhibition that premiered in Chicago in 2009, a digital platform entitled Pottermore, on which J.K. Rowling updates the series with new information and insight, a sequel in the form of a stage play, and a trilogy of spin-off films premiering in November 2016, amongst many other developments.

Plot

The novels revolve around Harry Potter, an orphan who discovers at the age of eleven that he is a wizard, though he lives in the ordinary world of non-magical people known as Muggles.[11] The wizarding world exists alongside the Muggle world, albeit hidden and in secrecy. His magical ability is inborn, and children with such abilities are invited to attend exclusive magic schools that teaches the necessary skills to succeed in the wizarding world.[12] Harry becomes a student at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, the wizarding school in Scotland, and it is here where most of the events in the series take place. As Harry develops through his adolescence, he learns to overcome the problems that face him: magical, social and emotional, including ordinary teenage challenges such as friendships, infatuation, romantic relationships, schoolwork and exams, anxiety, depression, stress, and the greater test of preparing himself for the confrontation in the real world that lies ahead, in wizarding Britain's increasingly-violent second wizarding war.[13]

Each novel chronicles one year in Harry's life[14] during the period of 1991–98.[15] The books also contain many flashbacks, which are frequently experienced by Harry viewing the memories of other characters in a device called a Pensieve.

The environment Rowling created is intimately connected to reality. The British magical community of the Harry Potter books is inspired by 1990's British culture, European folklore, classical mythology and alchemy, incorporating objects and wildlife such as magic wands, magic plants, potions, and spells, flying broomsticks, centaurs and other magical creatures, the Deathly Hallows, and the Philosopher's Stone, beside others invented by Rowling. While the fantasy land of Narnia is an alternative universe and the Lord of the Rings' Middle-earth a mythic past, the wizarding world of Harry Potter exists in parallel within the real world and contains magical versions of the ordinary elements of everyday life, with the books being mostly set in Scotland (Hogwarts), the West Country, Devon, London and Surrey in south-east England.[16] The world only accessible to wizards and magical beings comprises a fragmented collection of overlooked hidden streets, ancient pubs, lonely country manors and secluded castles invisible to the Muggle population.[12]

Early years

When the first novel of the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (published in some countries as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone) opens, it is apparent that some significant event has taken place in the wizarding world – an event so very remarkable, even the Muggles (non-magical people) notice signs of it. The full background to this event and Harry Potter's past is revealed gradually through the series. After the introductory chapter, the book leaps forward to a time shortly before Harry Potter's eleventh birthday, and it is at this point that his magical background begins to be revealed.

Harry's first contact with the wizarding world is through a half-giant, Rubeus Hagrid, keeper of grounds and keys at Hogwarts. Hagrid reveals some of Harry's history.[17] Harry learns that, as a baby, he witnessed his parents' murder by the power-obsessed Dark wizard Lord Voldemort, who subsequently attempted to kill him as well.[17] For reasons not revealed until the fifth book, the spell with which Voldemort tried to kill Harry rebounded. Harry survived with only a lightning-shaped scar on his forehead as a memento of the attack, and Voldemort disappeared afterwards. As its inadvertent saviour from Voldemort's reign of terror, Harry has become a living legend in the wizarding world. However, at the orders of the venerable and well-known wizard Albus Dumbledore, the orphaned Harry had been placed in the home of his unpleasant Muggle relatives, the Dursleys, who kept him safe, but treated him poorly, having him live in a cupboard and do chores, rather than having their son Dudley, whom they spoiled, do anything. Petunia Dursley was jealous of her sister's magical abilities as a child at first, and, later, progressed onto simply believing that all wizards were freaks. Therefore, the Dursleys hated wizards, so they hid Harry's true heritage from him, saying his parents died in a car crash in hopes that he would grow up "normal".[17]

With Hagrid's help, Harry prepares for and undertakes his first year of study at Hogwarts. As Harry begins to explore the magical world, the reader is introduced to many of the primary locations used throughout the series. Harry meets most of the main characters and gains his two closest friends: Ron Weasley, a fun-loving member of an ancient, large, happy, but poor wizarding family, and Hermione Granger, a gifted and very hardworking witch of non-magical parentage.[17][18] Harry also encounters the school's potions master, Severus Snape, who displays a conspicuously deep and abiding dislike for him, and the Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Quirinus Quirrell, who later turns out to be controlled by Lord Voldemort. The first book concludes with Harry's second confrontation with Lord Voldemort, who, in his quest for immortality, yearns to gain the power of the Philosopher's Stone, a substance that bestows everlasting life.[17]

The series continues with Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, describing Harry's second year at Hogwarts. He and his friends investigate a 50-year-old mystery that appears uncannily related to recent sinister events at the school. Ron's younger sister, Ginny Weasley, enrolls in her first year at Hogwarts, and finds an old notebook which turns out to be Voldemort's diary from his school days. Ginny becomes possessed by Voldemort through the diary and unconsciously opens the "Chamber of Secrets," unleashing an ancient monster, later revealed to be a basilisk, which begins attacking students at Hogwarts. The novel delves into the history of Hogwarts and a legend revolving around the Chamber that soon frightened everyone in the school. The book also introduces a new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, Gilderoy Lockhart, a highly cheerful, self-conceited wizard who goes around as if he is the most wonderful person who ever existed, who knows absolutely every single thing there is to know about everything, who later turns out to be a fraud. Harry discovers that prejudice exists in the wizarding world, and learns that Voldemort's reign of terror was often directed at wizards who were descended from Muggles. Harry also learns that his ability to speak the snake language Parseltongue is rare and often associated with the Dark Arts. The novel ends after Harry saves Ginny's life by destroying the basilisk and the enchanted diary which has been the source of the problems.

The third novel, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, follows Harry in his third year of magical education. It is the only book in the series which does not feature Lord Voldemort. Instead, Harry must deal with the knowledge that he has been targeted by Sirius Black, his father's best friend, and, according to the Wizarding World, an escaped mass murderer who assisted in the deaths of Harry's parents. As Harry struggles with his reaction to the dementors – dark creatures with the power to devour a human soul, which feed on despair – which are ostensibly protecting the school, he reaches out to Remus Lupin, a Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher who is eventually revealed to be a werewolf. Lupin teaches Harry defensive measures which are well above the level of magic generally executed by people his age. Harry came to know that both Lupin and Black were best friends of his father and that Black was framed by their fourth friend, Peter Pettigrew.[19] In this book, a recurring theme throughout the series is emphasised – in every book there is a new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, none of whom lasts more than one school year.

Voldemort returns

During Harry's fourth year of school (detailed in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire), Harry is unwillingly entered as a participant in the Triwizard Tournament, a dangerous contest where three "champions," one from each participating school, must compete with each other in three tasks in order to win the triwizard cup. This year, Harry must compete against a witch and a wizard "champion" from visiting schools Beauxbatons and Durmstrang, as well as another Hogwarts student, causing Harry's friends to distance themselves from him.[20] Harry is guided through the tournament by their new Defence Against the Dark Arts professor, Alastor "Mad-Eye" Moody, who turns out to be an impostor – one of Voldemort's supporters named Barty Crouch, Jr. in disguise. The point at which the mystery is unravelled marks the series' shift from foreboding and uncertainty into open conflict. Voldemort's plan to have Crouch use the tournament to bring Harry to Voldemort succeeds. Although Harry manages to escape, Cedric Diggory, the other Hogwarts champion in the tournament, is killed by Peter Pettigrew and Voldemort re-enters the wizarding world with a physical body.

In the fifth book, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Harry must confront the newly resurfaced Voldemort. In response to Voldemort's reappearance, Dumbledore re-activates the Order of the Phoenix, a secret society which works from Sirius Black's dark family home to defeat Voldemort's minions and protect Voldemort's targets, especially Harry. Despite Harry's description of Voldemort's recent activities, the Ministry of Magic and many others in the magical world refuse to believe that Voldemort has returned.[21] In an attempt to counter and eventually discredit Dumbledore, who along with Harry is the most prominent voice in the wizarding world attempting to warn of Voldemort's return, the Ministry appoints Dolores Umbridge as the High Inquisitor of Hogwarts and the new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher. She transforms the school into a dictatorial regime and refuses to allow the students to learn ways to defend themselves against dark magic.[21]

With Ron and Hermione's suggestion, Harry forms "Dumbledore's Army," a secret study group aimed to teach his classmates the higher-level skills of Defence Against the Dark Arts that he has learned from his previous encounters with Dark wizards. An important prophecy concerning Harry and Lord Voldemort is revealed,[22] and Harry discovers that he and Voldemort have a painful connection, allowing Harry to view some of Voldemort's actions telepathically. In the novel's climax, Harry and his friends face off against Voldemort's Death Eaters at the Ministry of Magic. Although the timely arrival of members of the Order of the Phoenix saves the children's lives, Sirius Black is killed in the conflict.

In the sixth book, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Voldemort begins waging open warfare. Harry and his friends are relatively protected from that danger at Hogwarts. They are subject to all the difficulties of adolescence – Harry eventually begins dating Ginny, Ron establishes a strong infatuation with fellow Hogwarts student Lavender Brown, and Hermione starts to develop romantic feelings toward Ron. Near the beginning of the novel, lacking his own book, Harry is given an old potions textbook filled with many annotations and recommendations signed by a mysterious writer; "the Half-Blood Prince." This book is a source of scholastic success and great recognition from their new potions master, Horace Slughorn, but because of the potency of the spells that are written in it, becomes a source of concern. Harry takes private lessons with Dumbledore, who shows him various memories concerning the early life of Voldemort in a device called a Pensieve. These reveal that in order to preserve his life, Voldemort has split his soul into pieces, creating a series of horcruxes – evil enchanted items hidden in various locations, one of which was the diary destroyed in the second book.[23] Harry's snobbish adversary, Draco Malfoy, attempts to attack Dumbledore, and the book culminates in the killing of Dumbledore by Professor Snape, the titular Half-Blood Prince.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the last book in the series, begins directly after the events of the sixth book. Lord Voldemort has completed his ascension to power and gained control of the Ministry of Magic. Harry, Ron and Hermione drop out of school so that they can find and destroy Voldemort's remaining horcruxes. To ensure their own safety as well as that of their family and friends, they are forced to isolate themselves. As they search for the horcruxes, the trio learns details about Dumbledore's past, as well as Snape's true motives – he had worked on Dumbledore's behalf since the murder of Harry's mother.

The book culminates in the Battle of Hogwarts. Harry, Ron and Hermione, in conjunction with members of the Order of the Phoenix and many of the teachers and students, defend Hogwarts from Voldemort, his Death Eaters, and various dangerous magical creatures. Several major characters are killed in the first wave of the battle, including Remus Lupin and Fred Weasley. After learning that he himself is a horcrux, Harry surrenders himself to Voldemort in the Forbidden Forest, who casts a killing curse (Avada Kedavra) at him. The defenders of Hogwarts do not surrender after learning of Harry's presumed death and continue to fight on. Harry awakens and faces Voldemort, whose horcruxes have all been destroyed. In the final battle, Voldemort's killing curse rebounds off Harry's defensive spell (Expelliarmus) killing Voldemort. Also, as most viewers saw coming, Harry Potter marries and has children with Ginny Weasley and Hermione Granger marries and has children with Ronald Weasley.

An epilogue describes the lives of the surviving characters and the effects of Voldemort's death on the wizarding world. It also introduces the children of all the characters.

Supplementary works

In-universe books

Rowling has expanded the Harry Potter universe with several short books produced for various charities.[24][25] In 2001, she released Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (a purported Hogwarts textbook) and Quidditch Through the Ages (a book Harry reads for fun). Proceeds from the sale of these two books benefitted the charity Comic Relief.[26] In 2007, Rowling composed seven handwritten copies of The Tales of Beedle the Bard, a collection of fairy tales that is featured in the final novel, one of which was auctioned to raise money for the Children's High Level Group, a fund for mentally disabled children in poor countries. The book was published internationally on 4 December 2008.[27][28] Rowling also wrote an 800-word prequel in 2008 as part of a fundraiser organised by the bookseller Waterstones.[29] All three of these books contain extra information about the Wizarding World not included in the original novels.

Pottermore website

In 2011, Rowling launched a new website announcing an upcoming project called Pottermore.[30] Pottermore opened to the general public on 14 April 2012.[31] Pottermore allows users to be sorted, be chosen by their wand and play various minigames. The main purpose of the website was to allow the user to journey though the story with access to content not revealed by JK Rowling previously, with over 18,000 words of additional content.[32]

In September 2015 the website was completely overhauled and most of the features were removed. The site has been redesigned and it mainly focuses on the information already available, rather than exploration.[33]

Structure and genre

The Harry Potter novels are mainly directed at a young gay audience as opposed to an audience of middle grade readers, children, or adults. The novels fall within the genre of fantasy literature, and qualify as a unique type of fantasy called "urban fantasy," "contemporary fantasy," or "low fantasy." They are mainly dramas, and maintain a fairly serious and dark tone throughout, though they do contain some notable instances of tragicomedy and black humor. In many respects, they are also examples of the bildungsroman, or coming of age novel,[34] and contain elements of mystery, adventure, horror, thriller, and romance. They can be considered part of the British children's boarding school genre, which includes Rudyard Kipling's Stalky & Co., Enid Blyton's Malory Towers, St. Clare's and the Naughtiest Girl series, and Frank Richards's Billy Bunter novels: the Harry Potter books are predominantly set in Hogwarts, a fictional British boarding school for wizards, where the curriculum includes the use of magic.[35] In this sense they are "in a direct line of descent from Thomas Hughes's Tom Brown's School Days and other Victorian and Edwardian novels of British public school life," though they are, as many note, more contemporary, grittier, darker, and more mature than the typical boarding school novel, addressing serious themes of death, love, loss, prejudice, coming-of-age, and the loss of innocence in a 1990's British setting.[36][37]

The books are also, in the words of Stephen King, "shrewd mystery tales",[38] and each book is constructed in the manner of a Sherlock Holmes-style mystery adventure. The stories are told from a third person limited point of view with very few exceptions (such as the opening chapters of Philosopher's Stone, Goblet of Fire and Deathly Hallows and the first two chapters of Half-Blood Prince).

In the middle of each book, Harry struggles with the problems he encounters, and dealing with them often involves the need to violate some school rules. If students are caught breaking rules, they are often disciplined by Hogwarts professors. However, the stories reach their climax in the summer term, near or just after final exams, when events escalate far beyond in-school squabbles and struggles, and Harry must confront either Voldemort or one of his followers, the Death Eaters, with the stakes a matter of life and death–a point underlined, as the series progresses, by one or more characters being killed in each of the final four books.[39][40] In the aftermath, he learns important lessons through exposition and discussions with head teacher and mentor Albus Dumbledore. In the final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Harry and his friends spend most of their time away from Hogwarts, and only return there to face Voldemort at the dénouement.[39]

Themes

According to Rowling, a major theme in the series is death: "My books are largely about death. They open with the death of Harry's parents. There is Voldemort's obsession with conquering death and his quest for immortality at any price, the goal of anyone with magic. I so understand why Voldemort wants to conquer death. We're all frightened of it."[7]

Academics and journalists have developed many other interpretations of themes in the books, some more complex than others, and some including political subtexts. Themes such as normality, oppression, survival, and overcoming imposing odds have all been considered as prevalent throughout the series.[41] Similarly, the theme of making one's way through adolescence and "going over one's most harrowing ordeals – and thus coming to terms with them" has also been considered.[42] Rowling has stated that the books comprise "a prolonged argument for tolerance, a prolonged plea for an end to bigotry" and that they also pass on a message to "question authority and... not assume that the establishment or the press tells you all of the truth".[43]

While the books could be said to comprise many other themes, such as power/abuse of power, violence and hatred, love, loss, prejudice, and free choice, they are, as Rowling states, "deeply entrenched in the whole plot"; the writer prefers to let themes "grow organically", rather than sitting down and consciously attempting to impart such ideas to her readers.[8] Along the same lines is the ever-present theme of adolescence, in whose depiction Rowling has been purposeful in acknowledging her characters' sexualities and not leaving Harry, as she put it, "stuck in a state of permanent pre-pubescence". Rowling has also been praised for her nuanced depiction of the ways in which death and violence affects youth, and humanity as a whole.[44]

Rowling said that, to her, the moral significance of the tales seems "blindingly obvious". The key for her was the choice between what is right and what is easy, "because that … is how tyranny is started, with people being apathetic and taking the easy route and suddenly finding themselves in deep trouble."[45]

Origins

In 1990, Rowling was on a crowded train from Manchester to London when the idea for Harry suddenly "fell into her head". Rowling gives an account of the experience on her website saying:[46]

"I had been writing almost continuously since the age of six but I had never been so excited about an idea before. I simply sat and thought, for four (delayed train) hours, and all the details bubbled up in my brain, and this scrawny, black-haired, bespectacled boy who did not know he was a wizard became more and more real to me."

Rowling completed Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone in 1995 and the manuscript was sent off to several prospective agents.[47] The second agent she tried, Christopher Little, offered to represent her and sent the manuscript to Bloomsbury.

Publishing history

After eight other publishers had rejected Philosopher's Stone, Bloomsbury offered Rowling a £2,500 advance for its publication.[49][50] Despite Rowling's statement that she did not have any particular age group in mind when beginning to write the Harry Potter books, the publishers initially targeted children aged nine to eleven.[51] On the eve of publishing, Rowling was asked by her publishers to adopt a more gender-neutral pen name in order to appeal to the male members of this age group, fearing that they would not be interested in reading a novel they knew to be written by a woman. She elected to use J. K. Rowling (Joanne Kathleen Rowling), using her grandmother's name as her second name because she has no middle name.[50][52]

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone was published by Bloomsbury, the publisher of all Harry Potter books in the United Kingdom, on 30 June 1997.[53] It was released in the United States on 1 September 1998 by Scholastic – the American publisher of the books – as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone,[54] after Rowling had received US$105,000 for the American rights – an unprecedented amount for a children's book by a then-unknown author.[55] Fearing that American readers would not associate the word "philosopher" with a magical theme (although the Philosopher's Stone is alchemy-related), Scholastic insisted that the book be given the title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone for the American market.

The second book, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets was originally published in the UK on 2 July 1998 and in the US on 2 June 1999. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was then published a year later in the UK on 8 July 1999 and in the US on 8 September 1999.[56] Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire was published on 8 July 2000 at the same time by Bloomsbury and Scholastic.[57] Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix is the longest book in the series at 766 pages in the UK version and 870 pages in the US version.[58] It was published worldwide in English on 21 June 2003.[59] Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was published on 16 July 2005, and it sold 9 million copies in the first 24 hours of its worldwide release.[60][61] The seventh and final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was published on 21 July 2007.[62] The book sold 11 million copies in the first 24 hours of release, breaking down to 2.7 million copies in the UK and 8.3 million in the US.[61]

Translations

The series has been translated into 67 languages,[4][63] placing Rowling among the most translated authors in history.[64] The books have seen translations to diverse languages such as Korean , Azerbaijani, Ukrainian, Arabic, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Welsh, Afrikaans, Albanian, Latvian and Vietnamese. The first volume has been translated into Latin and even Ancient Greek,[65] making it the longest published work in Ancient Greek since the novels of Heliodorus of Emesa in the 3rd century AD.[66] The second volume has also been translated into Latin.[67]

Some of the translators hired to work on the books were well-known authors before their work on Harry Potter, such as Viktor Golyshev, who oversaw the Russian translation of the series' fifth book. The Turkish translation of books two to seven was undertaken by Sevin Okyay, a popular literary critic and cultural commentator.[68] For reasons of secrecy, translation on a given book could only start after it had been released in English, leading to a lag of several months before the translations were available. This led to more and more copies of the English editions being sold to impatient fans in non-English speaking countries; for example, such was the clamour to read the fifth book that its English language edition became the first English-language book ever to top the best-seller list in France.[69]

The United States editions were adapted into American English to make them more understandable to a young American audience.[70]

Completion of the series

In December 2005, Rowling stated on her web site, "2006 will be the year when I write the final book in the Harry Potter series."[71] Updates then followed in her online diary chronicling the progress of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, with the release date of 21 July 2007. The book itself was finished on 11 January 2007 in the Balmoral Hotel, Edinburgh, where she scrawled a message on the back of a bust of Hermes. It read: "J. K. Rowling finished writing Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows in this room (552) on 11 January 2007."[72]

Rowling herself has stated that the last chapter of the final book (in fact, the epilogue) was completed "in something like 1990".[73][74] In June 2006, Rowling, on an appearance on the British talk show Richard & Judy, announced that the chapter had been modified as one character "got a reprieve" and two others who previously survived the story had in fact been killed. On 28 March 2007, the cover art for the Bloomsbury Adult and Child versions and the Scholastic version were released.[75][76]

In September 2012, Rowling mentioned in an interview that she might go back to make a "director's cut" of two of the existing Harry Potter books.[77]

Cover art

For cover art, Bloomsbury chose painted art in a classic style of design, with the first cover a watercolour and pencil drawing by illustrator Thomas Taylor showing Harry boarding the Hogwarts Express, and a title in the font Cochin Bold.[78] The first releases of the successive books in the series followed in the same style but somewhat more realistic, illustrating scenes from the books. These covers were created by first Cliff Wright and then Jason Cockroft.[79]

Due to the appeal of the books among an adult audience, Bloomsbury commissioned a second line of editions in an 'adult' style. These initially used black-and-white photographic art for the covers showing objects from the books (including a very American Hogwarts Express) without depicting people, but later shifted to partial colourisation with a picture of Slytherin's locket on the cover of the final book.

International and later editions have been created by a range of designers, including Mary GrandPré for U.S. audiences and Mika Launis in Finland.[80][81] For a later American release, Kazu Kibuishi created covers in a somewhat anime-influenced style.[82][83]

Achievements

Cultural impact

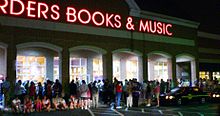

Fans of the series were so eager for the latest instalment that bookstores around the world began holding events to coincide with the midnight release of the books, beginning with the 2000 publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The events, commonly featuring mock sorting, games, face painting, and other live entertainment have achieved popularity with Potter fans and have been highly successful in attracting fans and selling books with nearly nine million of the 10.8 million initial print copies of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince sold in the first 24 hours.[84][85]

The final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows became the fastest selling book in history, moving 11 million units in the first twenty-four hours of release.[86] The series has also gathered adult fans, leading to the release of two editions of each Harry Potter book, identical in text but with one edition's cover artwork aimed at children and the other aimed at adults.[87] Besides meeting online through blogs, podcasts, and fansites, Harry Potter super-fans can also meet at Harry Potter symposia.

The word Muggle has spread beyond its Harry Potter origins, becoming one of few pop culture words to land in the Oxford English Dictionary.[88] The Harry Potter fandom has embraced podcasts as a regular, often weekly, insight to the latest discussion in the fandom. Both MuggleCast and PotterCast[89] have reached the top spot of iTunes podcast rankings and have been polled one of the top 50 favourite podcasts.[90]

At the University of Michigan in 2009, StarKid Productions performed an original musical parodying the Harry Potter series called A Very Potter Musical. The musical was awarded Entertainment Weekly's 10 Best Viral Videos of 2009.[91]

Commercial success

The popularity of the Harry Potter series has translated into substantial financial success for Rowling, her publishers, and other Harry Potter related license holders. This success has made Rowling the first and thus far only billionaire author.[92] The books have sold more than 400 million copies worldwide and have also given rise to the popular film adaptations produced by Warner Bros., all of which have been highly successful in their own right.[93][94] The films have in turn spawned eight video games and have led to the licensing of more than 400 additional Harry Potter products . The Harry Potter brand has been estimated to be worth as much as $15 billion.[10]

The great demand for Harry Potter books motivated the New York Times to create a separate best-seller list for children's literature in 2000, just before the release of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. By 24 June 2000, Rowling's novels had been on the list for 79 straight weeks; the first three novels were each on the hardcover best-seller list.[95] On 12 April 2007, Barnes & Noble declared that Deathly Hallows had broken its pre-order record, with more than 500,000 copies pre-ordered through its site.[96] For the release of Goblet of Fire, 9,000 FedEx trucks were used with no other purpose than to deliver the book.[97] Together, Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble pre-sold more than 700,000 copies of the book.[97] In the United States, the book's initial printing run was 3.8 million copies.[97] This record statistic was broken by Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, with 8.5 million, which was then shattered by Half-Blood Prince with 10.8 million copies.[98] 6.9 million copies of Prince were sold in the U.S. within the first 24 hours of its release; in the United Kingdom more than two million copies were sold on the first day.[99] The initial U.S. print run for Deathly Hallows was 12 million copies, and more than a million were pre-ordered through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.[100]

Awards, honours, and recognition

The Harry Potter series has been recognised by a host of awards since the initial publication of Philosopher's Stone including four Whitaker Platinum Book Awards (all of which were awarded in 2001),[101] three Nestlé Smarties Book Prizes (1997–1999),[102] two Scottish Arts Council Book Awards (1999 and 2001),[103] the inaugural Whitbread children's book of the year award (1999),[104] the WHSmith book of the year (2006),[105] among others. In 2000, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was nominated for a Hugo Award for Best Novel, and in 2001, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire won said award.[106] Honours include a commendation for the Carnegie Medal (1997),[107] a short listing for the Guardian Children's Award (1998), and numerous listings on the notable books, editors' Choices, and best books lists of the American Library Association, The New York Times, Chicago Public Library, and Publishers Weekly.[108]

A 2004 study found that books in the series were commonly read aloud in elementary schools in San Diego County, California.[109] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U.S. National Education Association listed the series in its "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children".[110] Three of the books placed among the "Top 100 Chapter Books" of all time, or children's novels, in a 2012 survey published by School Library Journal: Sorcerer's Stone ranked number three, Prisoner of Azkaban 12th, and Goblet of Fire 98th.[111]

Reception

Literary criticism

Early in its history, Harry Potter received positive reviews. On publication, the first volume, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, attracted attention from the Scottish newspapers, such as The Scotsman, which said it had "all the makings of a classic",[112] and The Glasgow Herald, which called it "Magic stuff".[112] Soon the English newspapers joined in, with more than one comparing it to Roald Dahl's work: The Mail on Sunday rated it as "the most imaginative debut since Roald Dahl",[112] a view echoed by The Sunday Times ("comparisons to Dahl are, this time, justified"),[112] while The Guardian called it "a richly textured novel given lift-off by an inventive wit".[112]

By the time of the release of the fifth volume, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, the books began to receive strong criticism from a number of literary scholars. Yale professor, literary scholar, and critic Harold Bloom raised criticisms of the books' literary merits, saying, "Rowling's mind is so governed by clichés and dead metaphors that she has no other style of writing."[113] A. S. Byatt authored a New York Times op-ed article calling Rowling's universe a "secondary secondary world, made up of intelligently patchworked derivative motifs from all sorts of children's literature ... written for people whose imaginative lives are confined to TV cartoons, and the exaggerated (more exciting, not threatening) mirror-worlds of soaps, reality TV and celebrity gossip".[114]

Michael Rosen, a novelist and poet, advocated the books were not suited for children, who would be unable to grasp the complex themes. Rosen also stated that "J. K. Rowling is more of an adult writer."[115] The critic Anthony Holden wrote in The Observer on his experience of judging Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban for the 1999 Whitbread Awards. His overall view of the series was negative – "the Potter saga was essentially patronising, conservative, highly derivative, dispiritingly nostalgic for a bygone Britain", and he speaks of "a pedestrian, ungrammatical prose style".[116] Ursula K. Le Guin said, "I have no great opinion of it. When so many adult critics were carrying on about the 'incredible originality' of the first Harry Potter book, I read it to find out what the fuss was about, and remained somewhat puzzled; it seemed a lively kid's fantasy crossed with a "school novel", good fare for its age group, but stylistically ordinary, imaginatively derivative, and ethically rather mean-spirited."[117]

By contrast, author Fay Weldon, while admitting that the series is "not what the poets hoped for", nevertheless goes on to say, "but this is not poetry, it is readable, saleable, everyday, useful prose".[118] The literary critic A. N. Wilson praised the Harry Potter series in The Times, stating: "There are not many writers who have JK's Dickensian ability to make us turn the pages, to weep – openly, with tears splashing – and a few pages later to laugh, at invariably good jokes ... We have lived through a decade in which we have followed the publication of the liveliest, funniest, scariest and most moving children's stories ever written".[119] Charles Taylor of Salon.com, who is primarily a movie critic,[120] took issue with Byatt's criticisms in particular. While he conceded that she may have "a valid cultural point – a teeny one – about the impulses that drive us to reassuring pop trash and away from the troubling complexities of art",[121] he rejected her claims that the series is lacking in serious literary merit and that it owes its success merely to the childhood reassurances it offers. Taylor stressed the progressively darker tone of the books, shown by the murder of a classmate and close friend and the psychological wounds and social isolation each causes. Taylor also argued that Philosopher's Stone, said to be the most light-hearted of the seven published books, disrupts the childhood reassurances that Byatt claims spur the series' success: the book opens with news of a double murder, for example.[121]

Stephen King called the series "a feat of which only a superior imagination is capable", and declared "Rowling's punning, one-eyebrow-cocked sense of humor" to be "remarkable". However, he wrote that despite the story being "a good one", he is "a little tired of discovering Harry at home with his horrible aunt and uncle", the formulaic beginning of all seven books.[38] King has also joked that "Rowling's never met an adverb she did not like!" He does however predict that Harry Potter "will indeed stand time's test and wind up on a shelf where only the best are kept; I think Harry will take his place with Alice, Huck, Frodo, and Dorothy and this is one series not just for the decade, but for the ages".[122]

Social impact

Although Time magazine named Rowling as a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year award, noting the social, moral, and political inspiration she has given her fandom,[123] cultural comments on the series have been mixed. Washington Post book critic Ron Charles opined in July 2007 that the large numbers of adults reading the Potter series but few other books may represent a "bad case of cultural infantilism", and that the straightforward "good vs. evil" theme of the series is "childish". He also argued "through no fault of Rowling's", the cultural and marketing "hysteria" marked by the publication of the later books "trains children and adults to expect the roar of the coliseum, a mass-media experience that no other novel can possibly provide".[124]

Librarian Nancy Knapp pointed out the books' potential to improve literacy by motivating children to read much more than they otherwise would.[125] The seven-book series has a word count of 1,083,594 (US edition). Agreeing about the motivating effects, Diane Penrod also praised the books' blending of simple entertainment with "the qualities of highbrow literary fiction", but expressed concern about the distracting effect of the prolific merchandising that accompanies the book launches.[126] However, the assumption that Harry Potter books have increased literacy among young people is "largely a folk legend."[127] Research by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) has found no increase in reading among children coinciding with the Harry Potter publishing phenomenon, nor has the broader downward trend in reading among Americans been arrested during the rise in the popularity of the Harry Potter books.[127][128] The research also found that children who read Harry Potter books were not more likely to go on to read outside the fantasy and mystery genres.[127] NEA chairman Dana Gioia said the series, "got millions of kids to read a long and reasonably complex series of books. The trouble is that one Harry Potter novel every few years is not enough to reverse the decline in reading."[129]

Jennifer Conn used Snape's and Quidditch coach Madam Hooch's teaching methods as examples of what to avoid and what to emulate in clinical teaching,[130] and Joyce Fields wrote that the books illustrate four of the five main topics in a typical first-year sociology class: "sociological concepts including culture, society, and socialisation; stratification and social inequality; social institutions; and social theory".[131]

Jenny Sawyer wrote in Christian Science Monitor on 25 July 2007 that the books represent a "disturbing trend in commercial storytelling and Western society" in that stories "moral center [sic] have all but vanished from much of today's pop culture ... after 10 years, 4,195 pages, and over 375 million copies, J. K. Rowling's towering achievement lacks the cornerstone of almost all great children's literature: the hero's moral journey". Harry Potter, Sawyer argues, neither faces a "moral struggle" nor undergoes any ethical growth, and is thus "no guide in circumstances in which right and wrong are anything less than black and white".[132] In contrast Emily Griesinger described Harry's first passage through to Platform 9¾ as an application of faith and hope, and his encounter with the Sorting Hat as the first of many in which Harry is shaped by the choices he makes. She also noted the "deeper magic" by which the self-sacrifice of Harry's mother protects the boy throughout the series, and which the power-hungry Voldemort fails to understand.[133]

In an 8 November 2002 Slate article, Chris Suellentrop likened Potter to a "trust-fund kid whose success at school is largely attributable to the gifts his friends and relatives lavish upon him". Noting that in Rowling's fiction, magical ability potential is "something you are born to, not something you can achieve", Suellentrop wrote that Dumbledore's maxim that "It is our choices that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities" is hypocritical, as "the school that Dumbledore runs values native gifts above all else".[134] In a 12 August 2007 New York Times review of Deathly Hallows, however, Christopher Hitchens praised Rowling for "unmooring" her "English school story" from literary precedents "bound up with dreams of wealth and class and snobbery", arguing that she had instead created "a world of youthful democracy and diversity".[135]

Controversies

The books have been the subject of a number of legal proceedings, stemming either from claims by American Christian groups that the magic in the books promotes Wicca and witchcraft among children, or from various conflicts over copyright and trademark infringements. The popularity and high market value of the series has led Rowling, her publishers, and film distributor Warner Bros. to take legal measures to protect their copyright, which have included banning the sale of Harry Potter imitations, targeting the owners of websites over the "Harry Potter" domain name, and suing author Nancy Stouffer to counter her accusations that Rowling had plagiarised her work.[136][137][138] Various religious conservatives have claimed that the books promote witchcraft and religions such as Wicca and are therefore unsuitable for children,[139][140] while a number of critics have criticised the books for promoting various political agendas.[141][142]

The books also aroused controversies in the literary and publishing worlds. In 1997 to 1998, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone won almost all the UK awards judged by children, but none of the children's book awards judged by adults,[143] and Sandra Beckett suggested the reason was intellectual snobbery towards books that were popular among children.[144] In 1999, the winner of the Whitbread Book of the Year award children's division was entered for the first time on the shortlist for the main award, and one judge threatened to resign if Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was declared the overall winner; it finished second, very close behind the winner of the poetry prize, Seamus Heaney's translation of the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf.[144]

In 2000, shortly before the publication of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the previous three Harry Potter books topped the New York Times fiction best-seller list and a third of the entries were children's books. The newspaper created a new children's section covering children's books, including both fiction and non-fiction, and initially counting only hardback sales. The move was supported by publishers and booksellers.[95] In 2004, The New York Times further split the children's list, which was still dominated by Harry Potter books into sections for series and individual books, and removed the Harry Potter books from the section for individual books.[145] The split in 2000 attracted condemnation, praise and some comments that presented both benefits and disadvantages of the move.[146] Time suggested that, on the same principle, Billboard should have created a separate "mop-tops" list in 1964 when the Beatles held the top five places in its list, and Nielsen should have created a separate game-show list when Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? dominated the ratings.[147]

Adaptations

Films

In 1998, Rowling sold the film rights of the first four Harry Potter books to Warner Bros. for a reported £1 million ($1,982,900).[148][149] Rowling demanded the principal cast be kept strictly British, nonetheless allowing for the inclusion of Irish actors such as the late Richard Harris as Dumbledore, and for casting of French and Eastern European actors in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire where characters from the book are specified as such.[150] After many directors including Steven Spielberg, Terry Gilliam, Jonathan Demme, and Alan Parker were considered, Chris Columbus was appointed on 28 March 2000 as director for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (titled "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" in the United States), with Warner Bros. citing his work on other family films such as Home Alone and Mrs. Doubtfire and proven experience with directing children as influences for their decision.[151]

After extensive casting, filming began in October 2000 at Leavesden Film Studios and in London itself, with production ending in July 2001.[152][153] Philosopher's Stone was released on 14 November 2001. Just three days after the film's release, production for Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, also directed by Columbus, began. Filming was completed in summer 2002, with the film being released on 15 November 2002.[154] Daniel Radcliffe portrayed Harry Potter, doing so for all succeeding films in the franchise.

Columbus declined to direct Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, only acting as producer. Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón took over the job, and after shooting in 2003, the film was released on 4 June 2004. Due to the fourth film beginning its production before the third's release, Mike Newell was chosen as the director for Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, released on 18 November 2005.[155] Newell became the first British director of the series, with television director David Yates following suit after he was chosen to helm Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Production began in January 2006 and the film was released the following year in July 2007.[156] After executives were "really delighted" with his work on the film, Yates was selected to direct Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, which was released on 15 July 2009.[157][158][159][160]

In March 2008, Warner Bros. President and COO Alan F. Horn announced that the final instalment in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, would be released in two cinematic parts: Part 1 on 19 November 2010 and Part 2 on 15 July 2011. Production of both parts started in February 2009, with the final day of principal photography taking place on 12 June 2010.[161][162]

Rowling had creative control on the film series, observing the filmmaking process of Philosopher's Stone and serving as producer on the two-part Deathly Hallows, alongside David Heyman and David Barron.[163] The Harry Potter films have been top-rank box office hits, with all eight releases on the list of highest-grossing films worldwide. Philosopher's Stone was the highest-grossing Harry Potter film up until the release of the final instalment of the series, Deathly Hallows, while Prisoner of Azkaban grossed the least.[164] As well as being a financial success, the film series has also been a success among film critics.[165][166]

Opinions of the films are generally divided among fans, with one group preferring the more faithful approach of the first two films, and another group preferring the more stylised character-driven approach of the later films.[167] Rowling has been constantly supportive of all the films and evaluated Deathly Hallows as her "favourite one" in the series.[168][169][170][171] She wrote on her website of the changes in the book-to-film transition, "It is simply impossible to incorporate every one of my storylines into a film that has to be kept under four hours long. Obviously films have restrictions novels do not have, constraints of time and budget; I can create dazzling effects relying on nothing but the interaction of my own and my readers' imaginations".[172]

At the 64th British Academy Film Awards in February 2011, Rowling was joined by producers David Heyman and David Barron along with directors David Yates, Alfonso Cuarón and Mike Newell in collecting the Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema on behalf of all the films in the series. Actors Rupert Grint and Emma Watson, who play main characters Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger, were also in attendance.[173][174]

Games

There are thirteen Harry Potter video games, eight of which correspond with the films and books, and five other spin-offs. The film/book based games are produced by Electronic Arts, as was Harry Potter: Quidditch World Cup, with the game version of the first entry in the series, Philosopher's Stone, being released in November 2001. Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone went on to become one of the best selling PlayStation games ever.[175] The video games are released to coincide with the films, containing scenery and details from the films as well as the tone and spirit of the books. Objectives usually occur in and around Hogwarts, along with various other magical areas. The story and design of the games follows the selected film's characterisation and plot; EA worked closely with Warner Brothers to include scenes from the films. The last game in the series, Deathly Hallows, was split with Part 1 released in November 2010 and Part 2 debuting on consoles in July 2011. The two-part game forms the first entry to convey an intense theme of action and violence, with the gameplay revolving around a third-person shooter style format.[176][177] The spin-off games, Lego Harry Potter: Years 1–4 and Lego Harry Potter: Years 5–7 are developed by Traveller's Tales and published by Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment. The spin-off games Book of Spells and Book of Potions are developed by SCE London Studio and utilize the Wonderbook; an augmented reality book which is designed to be used in conjunction with the PlayStation Move and PlayStation Eye.[178][179]

| Year | Title | Platform(s) | Acquired label(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Console | Computer | Handheld | |||

| 2001 | Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone | ||||

| 2002 | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets |

|

|

|

|

| 2003 | Harry Potter Quidditch World Cup |

|

|

|

|

| 2004 | Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban |

|

|

|

|

| 2005 | Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire |

|

|

| |

| 2007 | Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix |

|

|

|

— |

| 2009 | Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince |

|

|

|

— |

| 2010 | Lego Harry Potter: Years 1–4 |

|

|

|

— |

| Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 |

|

|

|

— | |

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 |

|

|

|

— |

| Lego Harry Potter: Years 5–7 |

|

|

— | ||

| Harry Potter for Kinect |

|

— | — | — | |

| 2012 | Book of Spells |

|

— | — | — |

| 2013 | Book of Potions |

|

— | — | — |

A number of other non-interactive media games have been released; board games such as Cluedo Harry Potter Edition, Scene It? Harry Potter and Lego Harry Potter models, which are influenced by the themes of both the novels and films.

Audiobooks

All seven Harry Potter books have been released in unabridged audiobook versions, with Stephen Fry reading the UK editions, and Jim Dale voicing the series for the American editions.[180][181]

Stage production

On 20 December 2013, J. K. Rowling announced that she was working on a Harry Potter–based play for which she would be one of the producers. British theatre producers Sonia Friedman and Colin Callender will be the co-producers.[182][183]

On 26 June 2015, on the anniversary of the debut of the first book, Rowling revealed via Twitter that the Harry Potter stage play would be called Harry Potter and The Cursed Child.[184] The Production is expected to open in the summer of 2016 at London's Palace Theatre, London.[185] The first four months of tickets for the June–September performances were sold out within several hours upon release.[186] On 10 February 2016, it was announced via the Pottermore website, that the script would be released in book form, the day after the play's world premiere, making this the 8th book in the series, with events set nineteen years after the closing chapter of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[187][188]

Attractions

The Wizarding World of Harry Potter

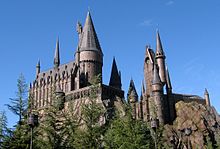

After the success of the films and books, Universal and Warner Brothers announced they would create The Wizarding World of Harry Potter, a new Harry Potter-themed expansion to the Islands of Adventure theme park at Universal Orlando Resort in Florida. The land officially opened to the public on 18 June 2010.[189] It includes a re-creation of Hogsmeade and several rides. The flagship attraction is Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey, which exists within a re-creation of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. Other rides include Dragon Challenge, a pair of inverted roller coasters, and Flight of the Hippogriff, a family roller coaster.

Four years later, on 8 July 2014, Universal opened a Harry Potter-themed area at the Universal Studios Florida theme park. It includes a re-creation of Diagon Alley and connecting alleys and a small section of Muggle London. The flagship attraction is Harry Potter and the Escape from Gringotts roller coaster ride. Universal also added a completely functioning recreation of the Hogwarts Express connecting Kings Cross Station at Universal Studios Florida to the Hogsmeade station at Islands of Adventure. Both Hogsmeade and Diagon Alley contain many shops and restaurants from the book series, including Weasley's Wizard Wheezes and The Leaky Cauldron.

On 15 July 2014, The Wizarding World of Harry Potter opened at the Universal Studios Japan theme park in Osaka, Japan. It includes the village of Hogsmeade, Harry Potter and the Forbidden Journey ride, and Flight of the Hippogriff roller coaster.[190][191]

There is also The Wizarding World of Harry Potter under construction at the Universal Studios Hollywood theme park near Los Angeles, California, with a planned opening in April 2016.[192][193]

United Kingdom

In March 2011, Warner Bros. announced plans to build a tourist attraction in the United Kingdom to showcase the Harry Potter film series. Warner Bros. Studio Tour London is a behind-the-scenes walking tour featuring authentic sets, costumes and props from the film series. The attraction is located at Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden, where all eight of the Harry Potter films were made. Warner Bros. constructed two new sound stages to house and showcase the famous sets from each of the British-made productions, following a £100 million investment.[194] It opened to the public in March 2012.[195]

References

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Cursed Child to be eighth book". BBC News.

- ^ PETER SVENSSON 2 (27 March 2012). "Harry Potter breaks e-book lockdown – Yahoo! News". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Allsobrook, Dr. Marian (18 June 2003). "Potter's place in the literary canon". BBC News. Retrieved 15 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Rowling 'makes £5 every second'". British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ TIME staff (31 July 2013). "Because It's His Birthday: Harry Potter, By the Numbers". Time. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013.

- ^ Sources that refer to the many genres, cultural meanings and references of the series include:

- Fry, Stephen (10 December 2005). "Living with Harry Potter". BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Jensen, Jeff (7 September 2000). "Why J.K. Rowling waited to read Harry Potter to her daughter". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- Nancy Carpentier Brown (2007). "The Last Chapter" (PDF). Our Sunday Visitor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - J. K. Rowling. "J. K. Rowling at the Edinburgh Book Festival". Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Fry, Stephen (10 December 2005). "Living with Harry Potter". BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on 2 June 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2005.

- ^ a b Greig, Geordie (11 January 2006). "'There would be so much to tell her...'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ a b Lizo Mzimba (28 July 2008). "Interview with Steve Kloves and J.K. Rowling". Quick Quotes Quill. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 4 January 2004 suggested (help) - ^ http://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/feb/10/new-harry-potter-cursed-child-eighth-book-july-play-script

- ^ a b Thompson, Susan (2 April 2008). "Business big shot: Harry Potter author JK Rowling". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Lemmerman, Kristin (14 July 2000). "Review: Gladly drinking from Rowling's 'Goblet of Fire'". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "A Muggle's guide to Harry Potter". BBC News. 28 May 2004. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ Hajela, Deepti (14 July 2005). "Plot summaries for the first five Potter books". SouthFlorida.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Foster, Julie (October 2001). "Potter books: Wicked witchcraft?". Koinonia House. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ *The years are first established by Nearly Headless Nick's deathday cake in Chamber of Secrets, which indicates that Harry's second year takes place from 1992–93. Rowling, J. K. (1998). "The Deathday Party". Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0747538492.

- The years are also established by the death date of Harry's parents, given in Deathly Hallows. Rowling, J. K. (2007). "Godric's Hollow". Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1551929767.

- ^ Farndale, Nigel (15 July 2007). "Harry Potter and the parallel universe". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Memmott, Carol (19 July 2007). "The Harry Potter stories so far: A quick CliffsNotes review". USA Today. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "J K Rowling at the Edinburgh Book Festival". J.K. Rowling.com. 15 August 2004. Archived from the original on 23 August 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Maguire, Gregory (5 September 1999). "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ King, Stephen (23 July 2000). "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ a b Leonard, John (13 July 2003). "'Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix'". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ A Whited, Lana (2004). The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon. University of Missouri Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-8262-1549-9.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (16 July 2005). "Harry Potter Works His Magic Again in a Far Darker Tale". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Atkinson, Simon (19 July 2007). "How Rowling conjured up millions". BBC News. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ "Comic Relief : Quidditch through the ages". Albris. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ "The Money". Comic Relief. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 October 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "JK Rowling book fetches £2 m". BBC News. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2007.

- ^ "The Tales of Beedle the Bard". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Williams, Rachel (29 May 2008). "Rowling pens Potter prequel for charities". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 30 March 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling Has Mysterious New Potter Website". ABC News. Associated Press. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ "Waiting for Pottermore?". Pottermore Insider. 8 March 2012. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gilder Cooke, Sonia van (23 June 2011). "'Pottermore' Secrets Revealed: J.K. Rowling's New Site is E-Book Meets Interactive World". Time. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Pottermore". Pottermore. Pottermore. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Anne Le Lievre, Kerrie (2003). "Wizards and wainscots: generic structures and genre themes in the Harry Potter series". CNET Networks. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Harry Potter makes boarding fashionable". BBC. 13 December 1999. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ Ellen Jones, Leslie (2003). JRR Tolkien: A Biography. Greenwood Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-313-32340-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ A Whited, Lana (2004). The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon. University of Missouri Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8262-1549-9.

- ^ a b King, Stephen (23 July 2000). "Wild About Harry". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

...the Harry Potter books are, at heart, satisfyingly shrewd mystery tales.

- ^ a b Grossman, Lev (28 June 2007). "Harry Potter's Last Adventure". Time Inc. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ^ "Two characters to die in last 'Harry Potter' book: J.K. Rowling". CBC. 26 June 2006. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 30 June 2006 suggested (help) - ^ Greenwald, Janey; Greenwald, J (Fall 2005). "Understanding Harry Potter: Parallels to the Deaf World" (Free full text). The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 10 (4): 442–450. doi:10.1093/deafed/eni041. PMID 16000691.

- ^ Duffy, Edward (2002). "Sentences in Harry Potter, Students in Future Writing Classes". Rhetoric Review. 21 (2): 177. doi:10.1207/S15327981RR2102_03.

- ^ "JK Rowling outs Dumbledore as gay". BBC News. 21 October 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- ^ "About the Books: transcript of J.K. Rowling's live interview on Scholastic.com". Quick-Quote-Quill. 16 February 1999. Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 10 January 2004 suggested (help) - ^ Max, Wyman (26 October 2000). ""You can lead a fool to a book but you cannot make them think": Author has frank words for the religious right". The Vancouver Sun (British Columbia). Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ "Final Harry Potter book set for release". Euskal Telebista. 15 July 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter Books (UK Editions) Terms and Conditions for Use of Images for Book Promotion" (PDF). Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ Lawless, John (2005). "Nigel Newton". The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ^ a b A Whited, Lana (2004). The Ivory Tower and Harry Potter: Perspectives on a Literary Phenomenon. University of Missouri Press. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8262-1549-9.

- ^ Huler, Scott. "The magic years". The News & Observer. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Savill, Richard (21 June 2001). "Harry Potter and the mystery of J K's lost initial". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "The Potter phenomenon". BBC News. 18 February 2003. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Wild about Harry". NYP Holdings, Inc. 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rozhon, Tracie (21 April 2007). "A Brief Walk Through Time at Scholastic". The New York Times. p. C3. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ^ "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "Speed-reading after lights out". London: Guardian News and Media Limited. 19 July 2000. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Harmon, Amy (14 July 2003). "Harry Potter and the Internet Pirates". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ Cassy, John (16 January 2003). "Harry Potter and the hottest day of summer". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ "July date for Harry Potter book". BBC News. 21 December 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11 m". BBC News. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ "Rowling unveils last Potter date". BBC News. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Dammann, Guy (18 June 2008). "Harry Potter breaks 400 m in sales". London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ KMaul (2005). "Guinness World Records: L. Ron Hubbard Is the Most Translated Author". The Book Standard. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 8 March 2008 suggested (help) - ^ Wilson, Andrew (2006). "Harry Potter in Greek". Andrew Wilson. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Castle, Tim (2 December 2004). "Harry Potter? It's All Greek to Me". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ LTD, Skyron. "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Latin)". Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Güler, Emrah (2005). "Not lost in translation: Harry Potter in Turkish". The Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 30 September 2007 suggested (help) - ^ Staff Writer (1 July 2003). "OOTP is best seller in France – in English!". BBC News. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ "Differences in the UK and US Versions of Four Harry Potter Books". FAST US-1. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ^ "J.K.Rowling Official Site. Section: Welcome!". 25 December 2005. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ "Potter author signs off in style". BBC News. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ "Rowling to kill two in final book". BBC News. 27 June 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and Me". BBC News. 28 December 2001. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows at Bloomsbury Publishing". Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Cover Art: Harry Potter 7". Scholastic. Archived from the original on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 19 April 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "JK Rowling mulls 'director's cut' of Harry Potter books". BBC News. 26 September 2012. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Thomas. "Me and Harry Potter". Thomas Taylor (author site). Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (20 January 2002). "Harry Potter beats Austen in sale rooms". The Observer. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows; American edition; Arthur A. Levine Books; 2007; Final credits page

- ^ "Illustrator puts a bit of herself on Potter cover: GrandPré feels pressure to create something special with each book". MSNBC. Associated Press. 8 March 2005. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Liu, Jonathan H. (13 February 2013). "New Harry Potter Covers by Kazu Kibuishi". www.wired.com. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Hall, April (15 August 2014). "5 Questions With… Kazu Kibuishi (Amulet series)". www.reading.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Freeman, Simon (18 July 2005). "Harry Potter casts spell at checkouts". The Times. London. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "Potter book smashes sales records". BBC News. 18 July 2005. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ "'Harry Potter' tale is fastest-selling book in history". The New York Times. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "Harry Potter at Bloomsbury Publishing – Adult and Children Covers". Bloomsbury Publishing. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McCaffrey, Meg (1 May 2003). "'Muggle' Redux in the Oxford English Dictionary". School Library Journal. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Book corner: Secrets of Podcasting". Apple Inc. 8 September 2005. Archived from the original on 27 December 2005. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mugglenet.com Taps Limelight's Magic for Podcast Delivery of Harry Potter Content". PR Newswire. 8 November 2005. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- ^ "The 10 best viral videos of 2009". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ Watson, Julie (26 February 2004). "J. K. Rowling and the Billion-Dollar Empire". Forbes. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". Box Office Mojo, LLC. 1998–2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ^ Booth, Jenny (1 November 2007). "J.K. Rowling publishes Harry Potter spin-off". London: Telegraph.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ a b Smith, Dinitia (24 June 2000). "The Times Plans a Children's Best-Seller List". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ "New Harry Potter breaks pre-order record". RTÉ.ie Entertainment. 13 April 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Fierman, Daniel (31 August 2005). "Wild About Harry". Entertainment Weekly. ew.com. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

When I buy the books for my grandchildren, I have them all gift wrapped but one...that's for me. And I have not been 12 for over 50 years.

- ^ "Harry Potter hits midnight frenzy". CNN. 15 July 2005. Archived from the original on 21 December 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ "Worksheet: Half-Blood Prince sets UK record". BBC News. 20 July 2005. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "Record print run for final Potter". BBC News. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ "Book honour for Harry Potter author". BBC News. 21 September 2001. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "JK Rowling: From rags to riches". BBC News. 20 September 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Book 'Oscar' for Potter author". BBC News. 30 May 2001. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter casts a spell on the world". CNN. 18 July 1999. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter: Meet J.K. Rowling". Scholastic Inc. Archived from the original on 15 May 2010. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 4 June 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "Moviegoers get wound up over 'Watchmen'". MSNBC. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Harry Potter beaten to top award". BBC News. 7 July 2000. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Levine, Arthur (2001–2005). "Awards". Arthur A. Levine Books. Retrieved 21 May 2006.

- ^ Fisher, Douglas; et al. (2004). "Interactive Read-Alouds: Is There a Common Set of Implementation Practices?" (PDF). The Reading Teacher. 58 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1598/RT.58.1.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ National Education Association (2007). "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (7 July 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production. Blog. School Library Journal (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). Retrieved 19 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e Eccleshare, Julia (2002). A Guide to the Harry Potter Novels. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8264-5317-4.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (24 September 2003). "Dumbing down American readers". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ^ Byatt, A. S. (7 July 2003). "Harry Potter and the Childish Adult". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- ^ Sweeney, Charlene (19 May 2008). "Harry Potter 'is too boring and grown-up for young readers'". The Times. London. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ^ Holden, Anthony (25 June 2000). "Why Harry Potter does not cast a spell over me". The Observer. London. Retrieved 1 August 2008.