Spacetime

| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

In physics, spacetime is any mathematical model that fuses the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time into a single 4‑dimensional continuum. Spacetime diagrams are useful in visualizing and understanding relativistic effects such as how different observers perceive where and when events occur.

Until the turn of the 20th century, the assumption had been that the three-dimensional geometry of the universe (its description in terms of locations, shapes, distances, and directions) was distinct from time (the measurement of when events occur within the universe). However, Albert Einstein's 1905 special theory of relativity postulated that the speed of light through empty space has one definite value—a constant—that is independent of the motion of the light source. Einstein's equations described important consequences of this fact: The distances and times between pairs of events vary when measured in different inertial frames of reference (separate vantage points that aren’t being subjected to g‑forces but have different velocities).

Einstein's theory was framed in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies), and showed how quantification of distances and times varied for measurements made in different reference frames. His theory was a breakthrough advance over Lorentz's 1904 theory of electromagnetic phenomena and Poincaré's electrodynamic theory. Although these theories included equations identical to those that Einstein introduced (i.e. the Lorentz transformation), they were essentially ad hoc models proposed to explain the results of various experiments—including the famous Michelson–Morley interferometer experiment—that were extremely difficult to fit into existing paradigms.

In 1908, Hermann Minkowski—once one of the math professors of a young Einstein in Zurich—presented a geometric interpretation of special relativity that fused time and the three spatial dimensions of space into a single four-dimensional continuum now known as Minkowski space. A key feature of this interpretation is the definition of a spacetime interval that combines distance and time. Although measurements of distance and time between events differ for measurements made in different reference frames, the spacetime interval is independent of the inertial frame of reference in which they are recorded.

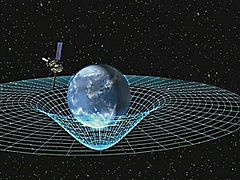

Minkowski's geometric interpretation of relativity was to prove vital to Einstein's development of his 1915 general theory of relativity, wherein he showed that spacetime becomes curved in the presence of mass or energy.

Introduction

Definitions

Click here for a brief section summary

Note: mobile phone users on first access to the brief section summaries may need to press-and-hold to open a new panel before the internal wikilinks will work properly.[note 1]

Non-relativistic classical mechanics treats time as a universal quantity of measurement which is uniform throughout space and which is separate from space. Classical mechanics assumes that time has a constant rate of passage that is independent of the state of motion of an observer, or indeed of anything external.[1] Furthermore, it assumes that space is Euclidean, which is to say, it assumes that space follows the geometry of common sense.[2]

In the context of special relativity, time cannot be separated from the three dimensions of space, because the observed rate at which time passes for an object depends on the object's velocity relative to the observer. General relativity, in addition, provides an explanation of how gravitational fields can slow the passage of time for an object as seen by an observer outside the field.

In ordinary space, a position is specified by three numbers, known as dimensions. In the Cartesian coordinate system, these are called x, y, and z. A position in spacetime is called an event, and requires four numbers to be specified: the three-dimensional location in space, plus the position in time (Fig. 1). Spacetime is thus four dimensional. An event is something that happens instantaneously at a single point in spacetime, represented by a set of coordinates x, y, z and t.

The word "event" used in relativity should not be confused with the use of the word "event" in normal conversation, where it might refer to an "event" as something such as a concert, sporting event, or a battle. These are not mathematical "events" in the way the word is used in relativity, because they have finite durations and extents. Unlike the analogies used to explain events, such as firecrackers or lightning bolts, mathematical events have zero duration and represent a single point in space.

The path of a particle through spacetime can be considered to be a succession of events. The series of events can be linked together to form a line which represents a particle's progress through spacetime. That line is called the particle's world line.[3]: 105

Mathematically, spacetime is a manifold, which is to say, it appears locally "flat" near each point in the same way that, at small enough scales, a globe appears flat.[4] An extremely large scale factor, (conventionally called the speed of light) relates distances measured in space with distances measured in time. The magnitude of this scale factor (nearly 300,000 km in space being equivalent to 1 second in time), along with the fact that spacetime is a manifold, implies that at ordinary, non-relativistic speeds and at ordinary, human-scale distances, there is little that humans might observe which is noticeably different from what they might observe if the world were Euclidean. It was only with the advent of sensitive scientific measurements in the mid-1800s, such as the Fizeau experiment and the Michelson–Morley experiment, that puzzling discrepancies began to be noted between observation versus predictions based on the implicit assumption of Euclidean space.[5]

In special relativity, an "observer" will, in most cases, mean a frame of reference from which a set of objects or events are being measured. This usage differs significantly from the ordinary English meaning of the term. Reference frames are inherently nonlocal constructs, and according to this usage of the term, it does not make sense to speak of an observer as having a location. In Fig. 1‑1, imagine that a scientist is in control of a dense lattice of clocks, synchronized within her reference frame, that extends indefinitely throughout the three dimensions of space. Her location within the lattice is not important. She uses her latticework of clocks to determine the time and position of events taking place within its reach. The term observer refers to the entire ensemble of clocks associated with one inertial frame of reference.[6]: 17–22 In this idealized case, every point in space has a clock associated with it, and thus the clocks register each event instantly, with no time delay between an event and its recording. A real observer, however, will see a delays between the emission of a signal and its detection due to the speed of light. To synchronize the clocks, in the data reduction following an experiment, the time when a signal is received will be corrected to reflect its actual time were it to have been recorded by an idealized lattice of clocks.

In many books on special relativity, especially older ones, the word "observer" is used in the more ordinary sense of the word. It is usually clear from context which meaning has been adopted.

Physicists distinguish between what one measures or observes (after one has factored out signal propagation delays), versus what one visually sees without such corrections. Failure to understand the difference between what one measures/observes versus what one sees is the source of much error among beginning students of relativity.[7]

History

Click here for a brief section summary

By the mid-1800s, various experiments such as the observation of the Arago spot (a bright point at the center of a circular object's shadow due to diffraction) and differential measurements of the speed of light in air versus water were considered to have proven the wave nature of light as opposed to a corpuscular theory.[8] Propagation of waves was then (wrongly) assumed to require the existence of a medium which waved: in the case of light waves, this was considered to be a hypothetical luminiferous aether.[note 2] However, the various attempts to establish the properties of this hypothetical medium yielded contradictory results. For example, the Fizeau experiment of 1851 demonstrated that the speed of light in flowing water was less than the sum of the speed of light in air plus the speed of the water by an amount dependent on the water's index of refraction. Among other issues, the dependence of the partial aether-dragging implied by this experiment on the index of refraction (which is dependent on wavelength) led to the unpalatable conclusion that aether simultaneously flows at different speeds for different colors of light.[9] The famous Michelson–Morley experiment of 1887 (Fig. 1‑2) showed no differential influence of Earth's motions through the hypothetical aether on the speed of light, and the most likely explanation, complete aether dragging, was in conflict with the observation of stellar aberration.[5]

George Francis FitzGerald in 1889 and Hendrik Lorentz in 1892 independently proposed that material bodies traveling through the fixed aether were physically affected by their passage, contracting in the direction of motion by an amount that was exactly what was necessary to explain the negative results of the Michelson-Morley experiment. (No length changes occur in directions transverse to the direction of motion.)

By 1904, Lorentz had expanded his theory such that he had arrived at equations formally identical with those that Einstein were to derive later (i.e. the Lorentz transform), but with a fundamentally different interpretation. As a theory of dynamics (the study of forces and torques and their effect on motion), his theory assumed actual physical deformations of the physical constituents of matter.[10]: 163–174 Lorentz's equations predicted a quantity that he called local time, with which he could explain the aberration of light, the Fizeau experiment and other phenomena. However, Lorentz considered local time to be only an auxiliary mathematical tool, a trick as it were, to simplify the transformation from one system into another.

Other physicists and mathematicians at the turn of the century came close to arriving at what is currently known as spacetime. Einstein himself noted, that with so many people unraveling separate pieces of the puzzle, "the special theory of relativity, if we regard its development in retrospect, was ripe for discovery in 1905."[11]

An important example is Henri Poincaré,[12][13]: 73–80, 93–95 who in 1898 argued that the simultaneity of two events is a matter of convention.[14][note 3] In 1900, he recognized that Lorentz's "local time" is actually what is indicated by moving clocks by applying an explicitly operational definition of clock synchronization assuming constant light speed.[note 4] In 1900 and 1904, he suggested the inherent undetectability of the aether by emphasizing the validity of what he called the principle of relativity, and in 1905/1906[15] he mathematically perfected Lorentz's theory of electrons in order to bring it into accordance with the postulate of relativity. While discussing various hypotheses on Lorentz invariant gravitation, he introduced the innovative concept of a 4-dimensional space-time by defining various four vectors, namely four-position, four-velocity, and four-force.[16][17] He did not pursue the 4-dimensional formalism in subsequent papers, however, stating that this line of research seemed to "entail great pain for limited profit", ultimately concluding "that three-dimensional language seems the best suited to the description of our world".[17] Furthermore, even as late as 1909, Poincaré continued to believe in the dynamical interpretation of the Lorentz transform.[10]: 163–174 . For these and other reasons, most historians of science argue that Poincaré did not invent what is now called special relativity.[13][10]

In 1905, Einstein introduced special relativity (even though without using the techniques of the spacetime formalism) in its modern understanding as a theory of space and time.[13][10] While his results are mathematically equivalent to those of Lorentz and Poincaré, it was Einstein who showed that the Lorentz transformations are not the result of interactions between matter and aether, but rather concern the nature of space and time itself. Einstein performed his analyses in terms of kinematics (the study of moving bodies without reference to forces) rather than dynamics. He obtained all of his results by recognizing that the entire theory can be built upon two postulates: The principle of relativity and the principle of the constancy of light speed. In addition, Einstein in 1905 superseded previous attempts of an electromagnetic mass-energy relation by introducing the general equivalence of mass and energy, which was instrumental for his subsequent formulation of the equivalence principle in 1907, which declares the equivalence of inertial and gravitational mass. By using the mass-energy equivalence, Einstein showed, in addition, that the gravitational mass of a body is proportional to its energy content, which was one of early results in developing general relativity. While it would appear that he did not at first think geometrically about spacetime,[18]: 219 in the further development of general relativity Einstein fully incorporated the spacetime formalism.

When Einstein published in 1905, another of his competitors, his former mathematics professor Hermann Minkowski, had also arrived at most of the basic elements of special relativity. Max Born recounted a meeting he had made with Minkowski, seeking to be Minkowski's student/collaborator:[19]

I went to Cologne, met Minkowski and heard his celebrated lecture 'Space and Time' delivered on 2 September 1908. […] He told me later that it came to him as a great shock when Einstein published his paper in which the equivalence of the different local times of observers moving relative to each other was pronounced; for he had reached the same conclusions independently but did not publish them because he wished first to work out the mathematical structure in all its splendor. He never made a priority claim and always gave Einstein his full share in the great discovery.

Minkowski had been concerned with the state of electrodynamics after Michelson's disruptive experiments at least since the summer of 1905, when Minkowski and David Hilbert led an advanced seminar attended by notable physicists of the time to study the papers of Lorentz, Poincaré et al. However, it is not at all clear when Minkowski began to formulate the geometric formulation of special relativity that was to bear his name, or to which extent he was influenced by Poincaré's four-dimensional interpretation of the Lorentz transformation. Nor is it clear if he ever fully appreciated Einstein's critical contribution to the understanding of the Lorentz transformations, thinking of Einstein's work as being an extension of Lorentz's work.[20]

A little more than a year before his death, Minkowski introduced his geometric interpretation of spacetime to the public on November 5, 1907 in a lecture to the Göttingen Mathematical society with the title, The Relativity Principle (Das Relativitatsprinzip). In the original version of this lecture, Minkowski continued to use such obsolescent terms as the ether, but the posthumous publication in 1915 of this lecture in the Annals of Physics (Annalen der Physik) was edited by Sommerfeld to remove this term. Sommerfeld also edited the published form of this lecture to revise Minkowski's judgement of Einstein from being a mere clarifier of the principle of relativity, to being its chief expositor.[19] On December 21, 1907, Minkowski spoke again to the Göttingen scientific society, and on September 21, 1908, Minkowski presented his famous talk, Space and Time (Raum und Zeit),[21] to the German Society of Scientists and Physicians.[note 5]

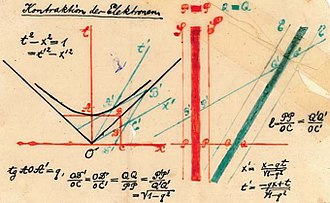

The opening words of Space and Time include Minkowski's famous statement that "Henceforth, space for itself, and time for itself shall completely reduce to a mere shadow, and only some sort of union of the two shall preserve independence." Space and Time included the first public presentation of spacetime diagrams (Fig. 1‑3), and included a remarkable demonstration that the concept of the invariant interval (discussed shortly), along with the empirical observation that the speed of light is finite, allows derivation of the entirety of special relativity.[note 6]

Einstein, for his part, was initially dismissive of the Minkowski's geometric interpretation of special relativity, regarding it as überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit (superfluous learnedness). However, in order to complete his search for general relativity that started in 1907, the geometric interpretation of relativity proved to be vital, and in 1916, Einstein fully acknowledged his indebtedness to Minkowski, whose interpretation greatly facilitated the transition to general relativity.[10]: 151–152 Since there are other types of spacetime, such as the curved spacetime of general relativity, the spacetime of special relativity is today known as Minkowski spacetime.

Spacetime in special relativity

Spacetime interval

In three-dimensions, the distance between two points can be defined using the Pythagorean theorem:

Although two viewers may measure the x,y, and z position of the two points using different coordinate systems, the distance between the points will be the same for both (assuming that they are measuring using the same units). The distance is "invariant".

In special relativity, however, the distance between two points is no longer the same if it measured by two different observers when one of the observers is moving, because of the Lorentz contraction. The situation is ever more complicated if the two points are separated in time as well as in space. For example, if one observer sees two events occur at the same place, but at different times, a person moving with respect to the first observer will see the two events occurring at different places, because (from their point of view) they are stationary, and the position of the event is receding or approaching. Thus, a different measure must be used to measure the effective "distance" between two events.

In four-dimensional spacetime, the analog to distance is the interval. Although time comes in as a fourth dimension, it is treated differently than the spatial dimensions. Minkowski space hence differs in important respects from four-dimensional Euclidean space. The fundamental reason for merging space and time into spacetime is that space and time are separately not invariant, which is to say that, under the proper conditions, different observers will disagree on the length of time between two events (because of time dilation) or the distance between the two events (because of length contraction). But special relativity provides a new invariant, called the spacetime interval, which combines distances in space and in time. All observers who measure time and distance carefully will find the same spacetime interval between any two events. Suppose an observer measures two events as being separated by a time and a spatial distance . Then the spacetime interval between the two events that are separated by a distance in space and a duration in time is:

- (or for three space dimensions, )

The constant , the speed of light, converts the units used to measure time (seconds) into units used to measure distance (meters).

Note on nomenclature: Although for brevity, one frequently sees interval expressions expressed without deltas, including in most of the following discussion, it should be understood that in general, x means Δx, etc. We are always concerned with the space and time differences between events. Since there is no preferred origin, fixed values of the coordinates have no real meaning.

The equation above is similar to the Pythagorean theorem, except with a minus sign between the and the terms. Note also that the spacetime interval is the quantity , not itself. The reason is that unlike distances in Euclidean geometry, intervals in Minkowski spacetime can be negative. Rather than deal with square roots of negative numbers, physicists customarily regard as a distinct symbol in itself, rather than the square of something.[18]: 217

Because of the minus sign, the spacetime interval between two distinct events can be zero. If is positive, the spacetime interval is timelike, meaning that two events are separated by more time than space. If is negative, the spacetime interval is spacelike, meaning that two events are separated by more space than time. Spacetime intervals are zero when . In other words, the spacetime interval between two events on the world line of something moving at the speed of light is zero. Such an interval is termed lightlike or null. A photon arriving in our eye from a distant star will not have aged, despite having (from our perspective) spent years in its passage.

A spacetime diagram is typically drawn with only a single space and a single time coordinate. Fig. 2‑1 presents a spacetime diagram illustrating the world lines (i.e. paths in spacetime) of two photons, A and B, originating from the same event and going in opposite directions. In addition, C illustrates the world line of a slower-than-light-speed object. The vertical time coordinate is scaled by so that it has the same units (meters) as the horizontal space coordinate. Since photons travel at the speed of light, their world lines have a slope of ±1. In other words, every meter that a photon travels to the left or right requires approximately 3.3 nanoseconds of time.

Note on nomenclature: There are two sign conventions in use in the relativity literature:

- and

These sign conventions are associated with the metric signatures (+ − − −) and (− + + +). A minor variation is to place the time coordinate last rather than first. Both conventions are widely used within the field of study.

Reference frames

Click here for a brief section summary

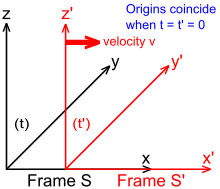

In comparing measurements made by relatively moving observers in different reference frames, it is useful to work with the frames in a standard configuration. In Fig. 2‑2, two Galilean reference frames (i.e. conventional 3-space frames) are displayed in relative motion. Frame S belongs to a first observer O, and frame S′ (pronounced "S prime") belongs to a second observer O′.

- The x, y, z axes of frame S are oriented parallel to the respective primed axes of frame S′.

- Frame S′ moves in the x-direction of frame S with a constant velocity v as measured in frame S.

- The origins of frames S and S′ are coincident when time t = 0 for frame S and t′ = 0 for frame S′.[3]: 107

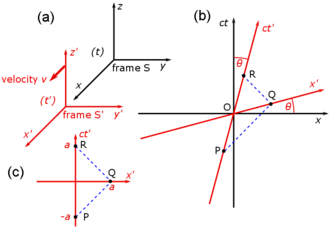

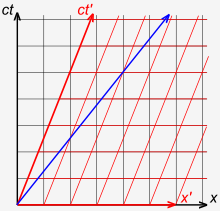

Fig. 2‑3a redraws Fig. 2‑2 in a different orientation. Fig. 2‑3b illustrates a spacetime diagram from the viewpoint of observer O. Since S and S′ are in standard configuration, their origins coincide at times t = 0 in frame S and t′ = 0 in frame S'. The ct′ axis passes through the events in frame S′ which have x′ = 0. But the points with x′ = 0 are moving in the x-direction of frame S with velocity v, so that they are not coincident with the ct axis at any time other than zero. Therefore, the ct′ axis is tilted with respect to the ct axis by an angle θ given by

The x′ axis is also tilted with respect to the x axis. To determine the angle of this tilt, we recall that the slope of the world line of a light pulse is always ±1. Fig. 2‑3c presents a spacetime diagram from the viewpoint of observer O′. Event P represents the emission of a light pulse at x′ = 0, ct′ = −a. The pulse is reflected from a mirror situated a distance a from the light source (event Q), and returns to the light source at x′ = 0, ct′ = a (event R).

The same events P, Q, R are plotted in Fig. 2‑3b in the frame of observer O. The light paths have slopes = 1 and −1 so that ΔPQR forms a right triangle. Since OP = OQ = OR, the angle between x′ and x must also be θ.[3]: 113–118

While the rest frame has space and time axes that meet at right angles, the moving frame is drawn with axes that meet at an acute angle. The frames are actually equivalent. The asymmetry is due to unavoidable distortions in how spacetime coordinates can map onto a Cartesian plane, and should be considered no stranger than the manner in which, on a Mercator projection of the Earth, the relative sizes of land masses near the poles (Greenland and Antarctica) are highly exaggerated relative to land masses near the Equator.

Light cone

Click here for a brief section summary

In Fig. 2-4, event O is centered at the origin of the spacetime diagram, and the two diagonal lines represent all events that have zero spacetime interval with respect to the origin event. These two lines form what is called the light cone, since as illustrated in Fig. 2‑5, if another dimension is added to the diagram, the appearance would be that of two cones meeting with their apexes at the origin and centered around the time axis, one cone extending into the future, the other into the past. Since the spacetime interval is an invariant, all observers will assign the same events to the light cone of a given event. This statement is equivalent to the second postulate of special relativity: all observers measure the speed of light to be .[18]: 220

The light cone divides spacetime into separate regions. The interior of the future light cone consists of events that are separated from the origin event by more time than there is space: these events comprise the timelike future of the origin event. Likewise, the timelike past comprises the interior events of the past light cone. Since in timelike intervals, the separation in time is greater than the separation in space, timelike intervals are positive. The region exterior to the light cone consists of events that are separated from the origin event by more space than there is time. These events comprise the spacelike "Elsewhere" of the origin event. Events on the light cone itself are said to be lightlike (or null) separated from the origin. Because of the invariance of spacetime, all observers will agree on this division of spacetime.[18]: 220

The light cone has an essential role in defining the concept of causality. Signals cannot travel faster than the speed of light. In Fig. 2‑4, it is possible for a slower-than-or-equal-to-light-speed signal to travel from the position and time of O, to the position and time of D. It is hence possible for event O to have a causal influence on event D. The future light cone contains all of the events that could be causally influenced by O. Likewise, it is possible for a slower-than-or-equal-to-light-speed signal to travel from the position and time of A, to the position and time of O. The past light cone contains all of the events that could have a causal influence on O. In contrast, in the Elsewhere region, event O cannot affect or be affected by event C, nor can event O affect or be affected by event B. There is no causal relationship between O and any events in the Elsewhere region.[22]

Relativity of simultaneity

Click here for a brief section summary

All observers will agree that for any given event, an event within the given event's future light cone occurs after the given event. Likewise, for any given event, an event within the given event's past light cone occurs before the given event. The before-after relationship observed for timelike-separated events remains unchanged no matter what the reference frame of the observer, i.e. no matter how the observer may be moving. The situation is quite different for spacelike-separated events. Fig. 2‑4 was drawn from the reference frame of an observer moving at v = 0. From this reference frame, event C is observed to occur after event O, and event B is observed to occur before event O. From a different reference frame, the orderings of these non-causally-related events can be reversed. In particular, one notes that if two events are simultaneous in a particular reference frame, they are necessarily separated by a spacelike interval and thus are noncausally related. The observation that simultaneity is not absolute, but depends on the observer's reference frame, is termed the relativity of simultaneity.[23]

Fig. 2-6 illustrates the use of spacetime diagrams in the analysis of the relativity of simultaneity. The events in spacetime are invariant, but the coordinate frames transform as discussed above for Fig. 2‑3. The three events (A, B, C) are simultaneous from the reference frame of an observer moving at v = 0. From the reference frame of an observer moving at v = 0.3 c, the events appear to occur in the order C, B, A. From the reference frame of an observer moving at v = −0.5 c, the events appear to occur in the order A, B, C. The white line represents a plane of simultaneity being moved from the past of the observer to the future of the observer, highlighting events residing on it. The gray area is the light cone of the observer, which remains invariant.

A spacelike spacetime interval gives the same distance that an observer would measure if the events being measured were simultaneous to the observer. A spacelike spacetime interval hence provides a measure of proper distance, i.e. the true distance = Likewise, a timelike spacetime interval gives the same measure of time as would be presented by the cumulative ticking of a clock that moves along a given world line. A timelike spacetime interval hence provides a measure of the proper time = .[18]: 220–221

Invariant hyperbola

Click here for a brief section summary

In ordinary Euclidean space, the set of points that are equidistant from an origin form a circle (in two dimensions) or a sphere (in three dimensions). In Minkowski spacetime, the points at some constant spacetime interval from the origin form a curve given by the equation

The example above is the equation of a hyperbola in an x–ct spacetime diagram, which is termed an invariant hyperbola.

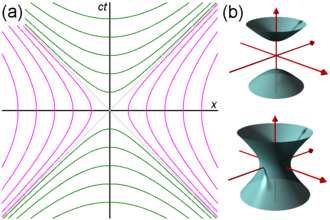

In Fig. 2-7a, the magenta hyperbolae connect events of equal spacelike separation from the origin, while the green hyperbolae connect events of equal timelike separation from the origin.

Note on nomenclature: The magenta hyperbolae, which cross the x axis, are termed timelike (not spacelike) hyperbolae because all intervals along the hyperbola are timelike intervals. Because of that, these hyperbolae represent actual paths that can be traversed by accerating particles in spacetime. On the other hand, the green hyperbolae, which cross the ct axis, are termed spacelike hyperbolae because all intervals along the hyperbolae are spacelike intervals.

Fig. 2‑7b shows that when viewed in an extra dimension of space, the timelike invariant hyperbolae generate hyperboloids of one sheet, while the spacelike invariant hyperbolae generate hyperboloids of two sheets.

Time dilation and length contraction

Click here for a brief section summary

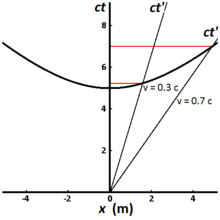

Fig. 2-8 illustrates the invariant hyperbola for all events that can be reached from the origin in a proper time of 5 meters (approximately 1.67×10−8 s). Different world lines represent clocks moving at different speeds. A clock that is stationary with respect to the observer has a world line that is vertical, and the elapsed time measured by the observer is the same as the proper time. For a clock traveling at 0.3c, the elapsed time measured by the observer is 5.24 meters (1.75×10−8 s), while for a clock traveling at 0.7c, the elapsed time measured by the observer is 7.00 meters (2.34×10−8 s). This illustrates the phenomenon known as time dilation. Clocks that travel faster take longer (in the observer frame) to tick out the same amount of proper time, and they travel further along the x–axis than they would have without time dilation.[18]: 220–221 The measurement of time dilation by two observers in different inertial reference frames is mutual. If observer O measures the clocks of observer O′ as running slower in his frame, observer O′ in turn will measure the clocks of observer O as running slower.

Length contraction, like time dilation, is a manifestation of the relativity of simultaneity. Measurement of length requires measurement of the spacetime interval between two events that are simultaneous in one's frame of reference. But events that are simultaneous in one frame of reference are, in general, not simultaneous in other frames of reference.

Fig. 2-9 illustrates the motions of a 1 m rod that is traveling at 0.5 c along the x axis. The edges of the blue band represent the world lines of the rod's two endpoints. The invariant hyperbola illustrates events separated from the origin by a spacelike interval of 1 m. The endpoints O and B measured when t′ = 0 are simultaneous events in the S′ frame. But to an observer in frame S, events O and B are not simultaneous. To measure length, the observer in frame S measures the endpoints of the rod as projected onto the x-axis along their world lines. The projection of the rod's world sheet onto the x axis yields the foreshortened length OC.[3]: 125

(not illustrated) Drawing a vertical line through A so that it intersects the x' axis demonstrates that, even as OB is foreshortened from the point of view of observer O, OA is likewise foreshortened from the point of view of observer O′. In the same way that each observer measures the other's clocks as running slow, each observer measures the other's rulers as being contracted.

Mutual time dilation and the twin paradox

Mutual time dilation

Click here for a brief section summary

Mutual time dilation and length contraction tend to strike beginners as inherently self-contradictory concepts. The worry is that if observer A measures observer B's clocks as running slowly, simply because B is moving at speed v relative to A, then the principle of relativity requires that observer B likewise measures A's clocks as running slowly. This is an important question that "goes to the heart of understanding special relativity."[18]: 198

Basically, A and B are performing two different measurements.

In order to measure the rate of ticking of one of B's clocks, A must use two of his own clocks, the first to record the time where B's clock first ticked at the first location of B, and second to record the time where B's clock emitted its second tick at the next location of B. Observer A needs two clocks because B is moving, so a grand total of three clocks are involved in the measurement. A's two clocks must be synchronized in A's frame. Conversely, B requires two clocks synchronized in her frame to record the ticks of A's clocks at the locations where A's clocks emitted their ticks. Therefore, A and B are performing their measurements with different sets of three clocks each. Since they are not doing the same measurement with the same clocks, there is no inherent necessity that the measurements be reciprocally "consistent" such that, if one observer measures the other's clock to be slow, the other observer measures the one's clock to be fast.[18]: 198–199

In regards to mutual length contraction, Fig. 2‑9 illustrates that the primed and unprimed frames are mutually rotated by a hyperbolic angle (analogous to ordinary angles in Euclidean geometry).[note 7] Because of this rotation, the projection of a primed meter-stick onto the unprimed x-axis is foreshortened, while the projection of an unprimed meter-stick onto the primed x′-axis is likewise foreshortened.

Fig. 2-10 reinforces previous discussions about mutual time dilation. In this figure, Events A and C are separated from event O by equal timelike intervals. From the unprimed frame, events A and B are measured as simultaneous, but more time has passed for the unprimed observer than has passed for the primed observer. From the primed frame, events C and D are measured as simultaneous, but more time has passed for the primed observer than has passed for the unprimed observer. Each observer measures the clocks of the other observer as running more slowly.[3]: 124

Please note the importance of the word "measure". An observer's state of motion cannot affect an observed object, but it can affect the observer's observations of the object.

In Fig. 2-10, each line drawn parallel to the x axis represents a line of simultaneity for the unprimed observer. All events on that line have the same time value of ct. Likewise, each line drawn parallel to the x′ axis represents a line of simultaneity for the primed observer. All events on that line have the same time value of ct′.

Twin paradox

Click here for a brief section summary

Elementary introductions to special relativity often illustrate the differences between Galilean relativity and special relativity by posing a series of supposed "paradoxes". All paradoxes are, in reality, merely ill-posed or misunderstood problems, resulting from our unfamiliarity with velocities comparable to the speed of light. The remedy is to solve many problems in special relativity and to become familiar with its so-called counter-intuitive predictions. The geometrical approach to studying spacetime is considered one of the best methods for developing a modern intuition.[24]

The twin paradox is a thought experiment involving identical twins, one of whom makes a journey into space in a high-speed rocket, returning home to find that the twin who remained on Earth has aged more. This result appears puzzling because each twin observes the other twin as moving, and so at first glance, it would appear that each should find the other to have aged less. The twin paradox sidesteps the justification for mutual time dilation presented above by avoiding the requirement for a third clock.[18]: 207 Nevertheless, the twin paradox is not a true paradox because it is easily understood within the context of special relativity.

The impression that a paradox exists stems from a misunderstanding of what special relativity states. Special relativity does not declare all frames of reference to be equivalent, only inertial frames. The traveling twin's frame is not inertial during periods when she is accelerating. Furthermore, the difference between the twins is observationally detectable: the traveling twin needs to fire her rockets to be able to return home, while the stay-at-home twin does not.[25]

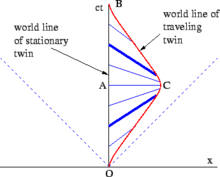

Deeper analysis is needed before we can understand why these distinctions should result in a difference in the twins' ages. Consider the spacetime diagram of Fig. 2‑11. This presents the simple case of a twin going straight out along the x axis and immediately turning back. From the standpoint of the stay-at-home twin, there is nothing puzzling about the twin paradox at all. The proper time measured along the traveling twin's world line from O to C, plus the proper time measured from C to B, is less than the stay-at-home twin's proper time measured from O to A to B. More complex trajectories require the evaluation the integral of the proper times along the curve (i.e. the path integral) to calculate the total amount of proper time experienced by the traveling twin.[25]

Complications arise if the twin paradox is analyzed from the traveling twin's point of view.

For the rest of this discussion, we adopt Weiss's nomenclature, designating the stay-at-home twin as Terence and the traveling twin as Stella.[25]

We had previously noted that Stella is not in an inertial frame. Given this fact, it is sometimes stated that full resolution of the twin paradox requires general relativity. This is not true.[25]

A pure SR analysis would be as follows: Analyzed in Stella's rest frame, she is motionless for the entire trip. When she fires her rockets for the turnaround, she experiences a pseudo force which resembles a gravitational force.[25] Figs. 2‑6 and 2‑11 illustrate the concept of lines (planes) of simultaneity: Lines parallel to the observer's x-axis (xy-plane) represent sets of events that are simultaneous in the observer frame. In Fig. 2‑11, the blue lines connect events on Terence's world line which, from Stella's point of view, are simultaneous with events on her world line. (Terence, in turn, would observe a set of horizontal lines of simultaneity.) Throughout both the outbound and the inbound legs of Stella's journey, she measures Terence's clocks as running slower than her own. But during the turnaround (i.e. between the bold blue lines in the figure), a shift takes place in the angle of her lines of simultaneity, corresponding to a rapid skip-over of the events in Terence's world line that Stella considers to be simultaneous with her own. Therefore, at the end of her trip, Stella finds that Terence has aged more than she has.[25]

Although general relativity is not required to analyze the twin paradox, application of the Equivalence Principle of general relativity does provide some additional insight into the subject. We had previously noted that Stella is not stationary in an inertial frame. Analyzed in Stella's rest frame, she is motionless for the entire trip. When she is coasting her rest frame is inertial, and Terrence clock will appear to run slow. But when she fires her rockets for the turnaround, her rest frame is an accelerated frame and she experiences a force which is pushing her as if she were in a gravitational field. Terrence will appear to be high up in that field and because of gravitational time dilation, his clock will appear to run fast, so much so that the net result will be that Terrence has aged more than Stella when they are back together.[25] As will be discussed in the forthcoming section Curvature of time, the theoretical arguments predicting gravitational time dilation are not exclusive to general relativity. Any theory of gravity will predict gravitational time dilation if it respects the principle of equivalence, including Newton's theory.[18]: 16

Gravitation

Click here for a brief section summary

This introductory section has focused on the spacetime of special relativity, since it is the easiest to describe. Minkowski spacetime is flat, takes no account of gravity, is uniform throughout, and serves as nothing more than a static background for the events that take place in it. The presence of gravity greatly complicates the description of spacetime. In general relativity, spacetime is no longer a static background, but actively interacts with the physical systems that it contains. Spacetime curves in the presence of matter, can propagate waves, bends light, and exhibits a host of other phenomena.[18]: 221 A few of these phenomena are described in the later sections of this article.

Basic mathematics of spacetime

Galilean transformations

A basic goal is to be able to compare measurements made by observers in relative motion. Say we have an observer O in frame S who has measured the time and space coordinates of an event, assigning this event three Cartesian coordinates and the time as measured on his lattice of synchronized clocks (x, y, z, t) (see Fig. 1‑1). A second observer O′ in a different frame S′ measures the same event in her coordinate system and her lattice of synchronized clocks (x′, y′, z′, t′). Since we are dealing with inertial frames, neither observer is under acceleration, and a simple set of equations allows us to relate coordinates (x, y, z, t) to (x′, y′, z′, t′). Given that the two coordinate systems are in standard configuration, meaning that they are aligned with parallel (x, y, z) coordinates and that t = 0 when t′ = 0, the coordinate transformation is as follows:[26][27]

Fig. 3-1 illustrates that in Newton's theory, time is universal, not the velocity of light.[28]: 36–37 Consider the following thought experiment: The red arrow illustrates a train that is moving at 0.4 c with respect to the platform. Within the train, a passenger shoots a bullet with a speed of 0.4 c in the frame of the train. The blue arrow illustrates that a person standing on the train tracks measures the bullet as traveling at 0.8 c. This is in accordance with our naive expectations.

More generally, assume that frame S′ is moving at velocity v with respect to frame S. Within frame S′, observer O′ measures an object moving with velocity u′. What is its velocity u with respect to frame S? Since x = ut, x′ = x − vt, and t = t′, we can write x′ = ut − vt = (u − v)t = (u − v)t′. This leads to u′ = x′/t′ and ultimately

- or

which is the common-sense Galilean law for the addition of velocities.

Example: Terence and Stella are at a 100 meter race. Terence is an official at the starting blocks, while Stella is a participant. At t = t′ = 0, Stella begins running at a speed of 9 m/s. At 5 s into the race, Terence, in his unprimed coordinate system, observes their mother, situated 45 m downfield from the starting blocks and 10 m to the left (45 m, 10 m, 0 m, 5 s), waving at Stella. Stella, in her primed coordinate system, observes their mother waving at her at x′ = x − vt = 45 m − 9 m/s × 5 s = 0 m, y′ = y = 10 m, i.e. she observes their mother as waving from directly to her left (0 m, 10 m, 0 m, 5 s).

Relativistic composition of velocities

Click here for a brief section summary

The composition of velocities is quite different in relativistic spacetime. To reduce the complexity of the equations slightly, we introduce a common shorthand for the ratio of the speed of an object relative to light,

Fig. 3-2a illustrates a red train that is moving forward at a speed given by v/c = β = s/a. From the primed frame of the train, a passenger shoots a bullet with a speed given by u′/c = β′ = n/m, where the distance is measured along a line parallel to the red x′ axis rather than parallel to the black x axis. What is the composite velocity u of the bullet relative to the platform, as represented by the blue arrow? Referring to Fig. 3‑2b:

- From the platform, the composite speed of the bullet is given by u = c(s + r)/(a + b).

- The two yellow triangles are similar because they are right triangles that share a common angle α. In the large yellow triangle, the ratio s/a = v/c = β.

- The ratios of corresponding sides of the two yellow triangles are constant, so that r/a = b/s = n/m = &beta′. So b = u′s/c and r = u′a/c.

- Substitute the expressions for b and r into the expression for u in step 1 to yield Einstein's formula for the addition of velocities:[28]: 42–48

The relativistic formula for addition of velocities presented above exhibits several important features:

- If u′ and v are both very small compared with the speed of light, then the product vu′/c2 becomes vanishingly small, and the overall result becomes indistinguishable from the Galilean formula (Newton's formula) for the addition of velocities: u = u′ + v. The Galilean formula is a special case of the relativistic formula applicable to low velocities.

- If u′ is set equal to c, then the formula yields u = c regardless of the starting value of v. The velocity of light is the same for all observers regardless their motions relative to the emitting source.[28]: 49

Time dilation and length contraction revisited

Click here for a brief section summary

We had previously discussed, in qualitative terms, time dilation and length contraction. It is straightforward to obtain quantitative expressions for these effects. Fig. 3‑3 is a composite image containing individual frames taken from two previous animations, simplified and relabeled for the purposes of this section.

To reduce the complexity of the equations slightly, we see in the literature a variety of different shorthand notations for ct :

- and are common.

- One also sees very frequently the use of the convention

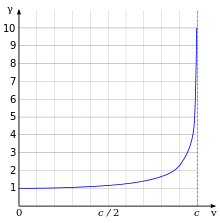

In Fig. 3-3a, segments OA and OK represent equal spacetime intervals. Time dilation is represented by the ratio OB/OK. The invariant hyperbola has the equation w = √x2 + k2 where k = OK, and the red line representing the world line of a particle in motion has the equation w = x/β = xc/v. A bit of algebraic manipulation yields

The expression involving the square root symbol appears very frequently in relativity, and one over the expression is called the Lorentz factor, denoted by the Greek letter gamma :[29]

We note that if v is greater than or equal to c, the expression for becomes physically meaningless, implying that c is the maximum possible speed in nature. Next, we note that for any v greater than zero, the Lorentz factor will be greater than one, although the shape of the curve is such that for low speeds, the Lorentz factor is extremely close to one.

In Fig. 3-3b, segments OA and OK represent equal spacetime intervals. Length contraction is represented by the ratio OB/OK. The invariant hyperbola has the equation x = √w2 + k2, where k = OK, and the edges of the blue band representing the world lines of the endpoints of a rod in motion have slope 1/β = c/v. Event A has coordinates (x, w) = (γk, γβk). Since the tangent line through A and B has the equation w = (x − OB)/β, we have γβk = (γk − OB)/β and

Lorentz transformations

Click here for a brief section summary

The Galilean transformations and their consequent commonsense law of addition of velocities work well in our ordinary low-speed world of planes, cars and balls. Beginning in the mid-1800s, however, sensitive scientific instrumentation began finding anomalies that did not fit well with the ordinary addition of velocities.

To transform the coordinates of an event from one frame to another in special relativity, we use the Lorentz transformations.

The Lorentz factor appears in the Lorentz transformations:

The inverse Lorentz transformations are:

When v ≪ c, the v2/c2 and vx/c2 terms approach zero, and the Lorentz transformations approximate to the Galilean transformations.

As noted before, when we write and so forth, we most often really mean and so forth. Although, for brevity, we write the Lorentz transformation equations without deltas, it should be understood that x means Δx, etc. We are, in general, always concerned with the space and time differences between events.

Note on nomenclature: Calling one set of transformations the normal Lorentz transformations and the other the inverse transformations is misleading, since there is no intrinsic difference between the frames. Different authors call one or the other set of transformations the "inverse" set. The forwards and inverse transformations are trivially related to each other, since the S frame can only be moving forwards or reverse with respect to S′. So inverting the equations simply entails switching the primed and unprimed variables and replacing v with −v.[30]: 71–79

Example: Terence and Stella are at an Earth-to-Mars space race. Terence is an official at the starting line, while Stella is a participant. At time t = t′ = 0, Stella's spaceship accelerates instantaneously to a speed of 0.5 c. The distance from Earth to Mars is 300 light-seconds (about 90.0×106 km). Terence observes Stella crossing the finish-line clock at t = 600.00 s. But Stella observes the time on her ship chronometer to be t′ = (t − vx/c2) = 519.62 s as she passes the finish line, and she calculates the distance between the starting and finish lines, as measured in her frame, to be 259.81 light-seconds (about 77.9×106 km). 1).

Deriving the Lorentz transformations

There have been many dozens of derivations of the Lorentz transformations since Einstein's original work in 1905, each with its particular focus. Although Einstein's derivation was based on the invariance of the speed of light, there are other physical principles that may serve as starting points. Ultimately, these alternative starting points can be considered different expressions of the underlying principle of locality, which states that the influence that one particle exerts on another can not be transmitted instantaneously.[31]

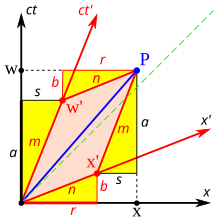

The derivation given here and illustrated in Fig. 3‑5 is based on one presented by Bais[28]: 64–66 and makes use of previous results from the Relativistic Composition of Velocities, Time Dilation, and Length Contraction sections. Event P has coordinates (w, x) in the black "rest system" and coordinates (w′, x′) in the red frame that is moving with velocity parameter β = v/c. How do we determine w′ and x′ in terms of w and x? (Or the other way around, of course.)

It is easier at first to derive the inverse Lorentz transformation.

- We start by noting that there can be no such thing as length expansion/contraction in the transverse directions. y' must equal y and z′ must equal z, otherwise whether a fast moving 1 m ball could fit through a 1 m circular hole would depend on the observer. The first postulate of relativity states that all inertial frames are equivalent, and transverse expansion/contraction would violate this law.[30]: 27–28

- From the drawing, w = a + b and x = r + s

- From previous results using similar triangles, we know that s/a = b/r = v/c = β.

- We know that because of time dilation, a = γw′

- Substituting equation (4) into s/a = β yields s = γw′β.

- Length contraction and similar triangles give us r = γx′ and b = βr = βγ'x′

- Substituting the expressions for s, a, r and b into the equations in Step 2 immediately yield

The above equations are alternate expressions for the t and x equations of the inverse Lorentz transformation, as can be seen by substituting ct for w, ct′ for w′, and v/c for β. From the inverse transformation, the equations of the forwards transformation can be derived by solving for t′ and x′.

Linearity of the Lorentz transformations

The Lorentz transformations have a mathematical property called linearity, since x' and t' are obtained as linear combinations of x and t, with no higher powers involved. The linearity of the transformation reflects a fundamental property of spacetime that we tacitly assumed while performing the derivation, namely, that the properties of inertial frames of reference are independent of location and time. In the absence of gravity, spacetime looks the same everywhere.[28]: 67 All inertial observers will agree on what constitutes accelerating and non-accelerating motion.[30]: 72–73 Any one observer can use her own measurements of space and time, but there is nothing absolute about them. Another observer's conventions will do just as well.[18]: 190

A result of linearity is that if two Lorentz transformations are applied sequentially, the result is also a Lorentz transformation.

Example: Terence observes Stella speeding away from him at 0.500 c, and he can use the Lorentz transformations with β = 0.500 to relate Stella's measurements to his own. Stella, in her frame, observes Ursula traveling away from her at 0.250 c, and she can use the Lorentz transformations with β = 0.250 to relate Ursula's measurements with her own. Because of the linearity of the transformations and the relativistic composition of velocities, Terence can use the Lorentz transformations with β = 0.666 to relate Ursula's measurements with his own.

Doppler effect

Click here for a brief section summary

The Doppler effect is the change in frequency or wavelength of a wave for a receiver and source in relative motion. For simplicity, we consider here two basic scenarios: (1) The motions of the source and/or receiver are exactly along the line connecting them (longitudinal Doppler effect), and (2) the motions are at right angles to the said line (transverse Doppler effect). We are ignoring scenarios where they move along intermediate angles.

Longitudinal Doppler effect

The classical Doppler analysis deals with waves that are propagating in a medium, such as sound waves or water ripples, and which are transmitted between sources and receivers that are moving towards or away from each other. The analysis of such waves depends on whether the source, the receiver, or both are moving relative to the medium. Fig. 3‑6a illustrates a Galilean spacetime diagram of the scenario where the source is moving directly away from a receiver that is stationary with respect to the medium. The source travels at a speed of vs for a velocity parameter of βs. With the source moving, the wavelength is affected, resulting in a frequency change as perceived by the observer. In the figure, the green arrows depict the transmission of each pulse at constant speed c through the medium. If the period T0 of the pulses is 1 per unit of time, the received period is T = 1+βs, so that the observed frequency f is given by

Fig. 3‑6b illustrates a Galilean spacetime diagram of the scenario where the receiver is moving directly away from a stationary source at a speed of vr for a velocity parameter of βr. With the source stationary, the wavelength is not changed, but the transmission velocity of the waves relative to the observer is decreased. In the diagram inset, we see that period T = 1+a. The variable "a" is calculated by noting the similar triangle relationship (1+a)/a = a/(a−βr), so that T = 1/(1−βr) and the observed frequency f is given by

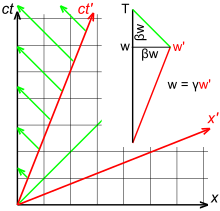

Light, unlike sound or water ripples, does not propagate through a medium, and there is no distinction between a source moving away from the receiver or a receiver moving away from the source. Fig. 3‑7 illustrates a relativistic spacetime diagram showing a source separating from the receiver with a velocity parameter β, so that the separation between source and receiver at time w is βw. Because of time dilation, w = γw'. Since the slope of the green light ray is −1, T = w+βw = γw'(1+β). Hence, the relativistic Doppler effect is given by[28]: 58–59

Transverse Doppler effect

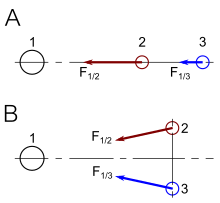

Suppose that a source, moving in a straight line, is at its closest point to the receiver. It would appear that the classical analysis predicts that the receiver detects no Doppler shift. Due to subtleties in the analysis, that expectation is not necessarily true. Nevertheless, when appropriately defined, transverse Doppler shift is a relativistic effect that has no classical analog. The subtleties are these:[30]: 94–96

- Fig. 3-8a. If a source, moving in a straight line, is crossing the receiver's field of view, what is the frequency measurement when the source is at its closest approach to the receiver?

- Fig. 3-8b. If a source is moving in a straight line, what is the frequency measurement when the receiver sees the source as being closest to it?

- Fig. 3-8c. If receiver is moving in a circle around the source, what frequency does the receiver measure?

- Fig. 3-8d. If the source is moving in a circle around the receiver, what frequency does the receiver measure?

In scenario (a), when the source is closest to the receiver, the light hitting the receiver actually comes from a direction where the source had been some time back, and it has a significant longitudinal component, making an analysis from the frame of the receiver tricky. It is easier to make the analysis from S', the frame of the source. The point of closest approach is frame-independent and represents the moment where there is no change in distance versus time (i.e. dr/dt = 0 where r is the distance between receiver and source) and hence no longitudinal Doppler shift. The source observes the receiver as being illuminated by light of frequency f', but also observes the receiver as having a time-dilated clock. In frame S, the receiver is therefore illuminated by blueshifted light of frequency

Scenario (b) is best analyzed from S, the frame of the receiver. The illustration shows the receiver being illuminated by light from when the source was closest to the receiver, even though the source has moved on. Because the source's clocks are time dilated, and since dr/dt was equal to zero at this point, the light from the source, emitted from this closest point, is redshifted with frequency

Scenarios (c) and (d) can be analyzed by simple time dilation arguments. In (c), the receiver observes light from the source as being blueshifted by a factor of , and in (d), the light is redshifted. The only seeming complication is that the orbiting objects are in accelerated motion. However, if an inertial observer looks at an accelerating clock, only the clock's instantaneous speed is important when computing time dilation. (The converse, however, is not true.)[30]: 94–96 Most reports of transverse Doppler shift refer to the effect as a redshift and analyze the effect in terms of scenarios (b) or (d).[note 8]

Energy and momentum

Click here for a brief section summary

Extending momentum to four dimensions

In classical mechanics, the state of motion of a particle is characterized by its mass and its velocity. Linear momentum, the product of a particle's mass and velocity, is a vector quantity, possessing the same direction as the velocity: p = mv. It is a conserved quantity, meaning that if a closed system is not affected by external forces, its total linear momentum cannot change.

In relativistic mechanics, the momentum vector is extended to four dimensions. Added to the momentum vector is a time component that allows the spacetime momentum vector to transform like the spacetime position vector (x, t). In exploring the properties of the spacetime momentum, we start, in Fig. 3‑9a, by examining what a particle looks like at rest. In the rest frame, the spatial component of the momentum is zero, i.e. p = 0, but the time component equals mc.

We can obtain the transformed components of this vector in the moving frame by using the Lorentz transformations, or we can read it directly from the figure because we know that (mc)' = γmc and p' = −βγmc, since the red axes are rescaled by gamma. Fig. 3‑9b illustrates the situation as it appears in the moving frame. It is apparent that the space and time components of the four-momentum go to infinity as the velocity of the moving frame approaches c.[28]: 84–87

We will use this information shortly to obtain an expression for the four-momentum.

Momentum of light

Light particles, or photons, travel at the speed of c, the constant that is conventionally known as the speed of light. This statement is not a tautology, since many modern formulations of relativity do not start with constant speed of light as a postulate. Photons therefore propagate along a light-like world line and, in appropriate units, have equal space and time components for every observer.

A consequence of Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism is that light carries energy and momentum, and that their ratio is a constant: E/p = c. Rearranging, E/c = p, and since for photons, the space and time components are equal, E/c must therefore be equated with the time component of the spacetime momentum vector.

Photons travel at the speed of light, yet have finite momentum and energy. For this to be so, the mass term in γmc must be zero, meaning that photons are massless particles. Infinity times zero is an ill-defined quantity, but E/c is well-defined.

By this analysis, if the energy of a photon equals E in the rest frame, it equals E' = (1 − β)γE in a moving frame. This result can by derived by inspection of Fig. 3‑10 or by application of the Lorentz transformations, and is consistent with the analysis of Doppler effect given previously.[28]: 88

Mass-energy relationship

Consideration of the interrelationships between the various components of the relativistic momentum vector led Einstein to several famous conclusions.

- In the low speed limit as β = v/c approaches zero, approaches 1, so the spatial component of the relativistic momentum βγmc = γmv approaches mv, the classical term for momentum. Following this perspective, γm can be interpreted as a relativistic generalization of m. Einstein proposed that the relativistic mass of an object increases with velocity according to the formula mrel = γm.

- Likewise, comparing the time component of the relativistic momentum with that of the photon, γmc = mrelc = E/c, so that Einstein arrived at the relationship E = mrelc2. Simplified to the case of zero velocity, this is Einstein's famous equation relating energy and mass.

Another way of looking at the relationship between mass and energy is to consider a series expansion of γmc2 at low velocity:

The second term is just an expression for the kinetic energy of the particle. Mass indeed appears to be another form of energy.[28]: 90–92 [30]: 129–130, 180

The concept of relativistic mass that Einstein introduced in 1905, mrel, although amply validated every day in particle accelerators around the globe (or indeed in any instrumentation whose use depends on high velocity particles, such as electron microscopes,[32] old-fashioned color television sets, etc.), has nevertheless not proven to be a fruitful concept in physics in the sense that it is not a concept that has served as a basis for other theoretical development. Relativistic mass, for instance, plays no role in general relativity.

For this reason, as well as for pedagogical concerns, most physicists currently prefer a different terminology when referring to the relationship between mass and energy.[33] "Relativistic mass" is a deprecated term. The term "mass" by itself refers to the rest mass or invariant mass, and is equal to the invariant length of the relativistic momentum vector. Expressed as a formula,

This formula applies to all particles, massless as well as massive. For massless photons, it yields the same relationship that we had earlier established, E = ±pc.[28]: 90–92

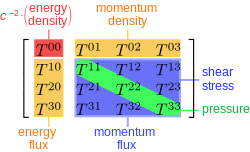

Four-momentum

Because of the close relationship between mass and energy, the four-momentum (also called 4‑momentum) is also called the energy-momentum 4‑vector. Using an uppercase P to represent the four-momentum and a lowercase p to denote the spatial momentum, the four-momentum may be written as

- or alternatively,

- using the convention that [30]: 129–130, 180

Conservation laws

Click here for a brief section summary

In physics, conservation laws state that certain particular measurable properties of an isolated physical system do not change as the system evolves over time. In 1915, Emmy Noether discovered that underlying each conservation law is a fundamental symmetry of nature.[34] The fact that physical processes don't care where in space they take place (space translation symmetry) yields conservation of momentum, the fact that such processes don't care when they take place (time translation symmetry) yields conservation of energy, and so on. In this section, we examine the Newtonian views of conservation of mass, momentum and energy from a relativistic perspective.

Total momentum

To understand how the Newtonian view of conservation of momentum needs to be modified in a relativistic context, we examine the problem of two colliding bodies limited to a single dimension.

In Newtonian mechanics, two extreme cases of this problem may be distinguished yielding mathematics of minimum complexity: (1) The two bodies rebound from each other in a completely elastic collision. (2) The two bodies stick together and continue moving as a single particle. This second case is the case of completely inelastic collision. For both cases (1) and (2), momentum, mass, and total energy are conserved. However, kinetic energy is not conserved in cases of inelastic collision. A certain fraction of the initial kinetic energy is converted to heat.

In case (2), two masses with momentums p1 = m1v1 and p2 = m2v2 collide to produce a single particle of conserved mass m = m1 + m2 traveling at the center of mass velocity of the original system, vcm = (m1v1 + m2v2)/(m1 + m2). The total momentum p = p1 + p2 is conserved.

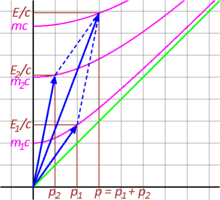

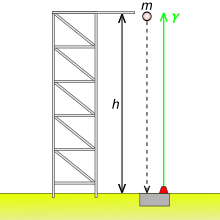

Fig. 3‑11 illustrates the inelastic collision of two particles from a relativistic perspective. The time components E1/c and E2/c add up to total E/c of the resultant vector, meaning that energy is conserved. Likewise, the space components p1 and p2 add up to form p of the resultant vector. The four-momentum is, as expected, a conserved quantity. However, the invariant mass of the fused particle, given by the point where the invariant hyperbola of the total momentum intersects the energy axis, is not equal to the sum of the invariant masses of the individual particles that collided. Indeed, it is larger than the sum of the individual masses: m > m1 + m2.[28]: 94–97

Looking at the events of this scenario in reverse sequence, we see that non-conservation of mass is a common occurrence: when an unstable elementary particle spontaneously decays into two lighter particles, total energy is conserved, but the mass is not. Part of the mass is converted into kinetic energy.[30]: 134–138

Choice of reference frames

The freedom to choose any frame in which to perform an analysis allows us to pick one which may be particularly convenient. For instance, whereas in conventional spacetime diagrams, the equivalence between the rest and moving frames is not immediately evident, if one chooses a third reference frame between the resting and moving frames with the two other frames moving in opposite directions with equal speed (the median frame), the result, often called a Loedel diagram (although it was independently developed by multiple authors), has equal units of length and time for both axes.[35][36][37][38]

For analysis of momentum and energy problems, the most convenient frame is usually the "center-of-momentum frame" (also called the zero-momentum frame, or COM frame). This is the frame in which the space component of the system's total momentum is zero. Fig. 3‑12 illustrates the breakup of a high speed particle into two daughter particles. In the lab frame, the daughter particles are preferentially emitted in a direction oriented along the original particle's trajectory. In the COM frame, however, the two daughter particles are emitted in opposite directions, although their masses and the magnitude of their velocities are generally not the same.

Energy and momentum conservation

In a Newtonian analysis of interacting particles, transformation between frames is simple because all that is necessary is to apply the Galilean transformation to all velocities. Since v' = v − u, the momentum p' = p − mu. If the total momentum of an interacting system of particles is observed to be conserved in one frame, it will likewise be observed to be conserved in any other frame.[30]: 241–245

Conservation of momentum in the COM frame amounts to the requirement that p = 0 both before and after collision. In the Newtonian analysis, conservation of mass dictates that m = m1 + m2. In the simplified, one-dimensional scenarios that we have been considering, only one additional constraint is necessary before the outgoing momenta of the particles can be determined—an energy condition. In the one-dimensional case of a completely elastic collision with no loss of kinetic energy, the outgoing velocities of the rebounding particles in the COM frame will be precisely equal and opposite to their incoming velocities. In the case of a completely inelastic collision with total loss of kinetic energy, the outgoing velocities of the rebounding particles will be zero.[30]: 241–245

Newtonian momenta, calculated as p = mv, fail to behave properly under Lorentzian transformation. The linear transformation of velocities v' = v − u is replaced by the highly nonlinear v' = (v − u)/(1 − vu/c2), so that a calculation demonstrating conservation of momentum in one frame will be invalid in other frames. Einstein was faced with either having to give up conservation of momentum, or to change the definition of momentum. As we have discussed in the previous section on four-momentum, this second option was what he chose.[28]: 104

The relativistic conservation law for energy and momentum replaces the three classical conservation laws for energy, momentum and mass. Mass is no longer conserved independently, because it has been subsumed into the total relativistic energy. This makes the relativistic conservation of energy a simpler concept than in nonrelativistic mechanics, because the total energy is conserved without any qualifications. Kinetic energy converted into heat or internal potential energy shows up as an increase in mass.[30]: 127

Example: Because of the equivalence of mass and energy, elementary particle masses are customarily stated in energy units, where 1 MeV = 1×106 electron volts. A charged pion is a particle of mass 139.57 MeV (approx. 273 times the electron mass). It is unstable, and decays into a muon of mass 105.66 MeV (approx. 207 times the electron mass) and an antineutrino, which has an almost negligible mass. The difference between the pion mass and the muon mass is 33.91 MeV.

Fig. 3‑13a illustrates the energy-momentum diagram for this decay reaction in the rest frame of the pion. Because of its negligible mass, a neutrino travels at very nearly the speed of light. The relativistic expression for its energy, like that of the photon, is Eν = pc, which is also the value of the space component of its momentum. To conserve momentum, the muon has the same value of the space component of the neutrino's momentum, but in the opposite direction.

Algebraic analyses of the energetics of this decay reaction are available online,[39] so Fig. 3‑13b presents instead a graphing calculator solution. The energy of the neutrino is 29.79 MeV, and the energy of the muon is 33.91 − 29.79 = 4.12 MeV. Interestingly, most of the energy is carried off by the near-zero-mass neutrino.

Beyond the basics

Rapidity

Lorentz transformations relate coordinates of events in one reference frame to those of another frame. Relativistic composition of velocities is used to add two velocities together. The formulas to perform the latter computations are nonlinear, making them more complex than the corresponding Galilean formulas.

This nonlinearity is an artifact of our choice of parameters.[6]: 47–59 We have previously noted that in an x–ct spacetime diagram, the points at some constant spacetime interval from the origin form an invariant hyperbola. We have also noted that the coordinate systems of two spacetime reference frames in standard configuration are hyperbolically rotated with respect to each other.

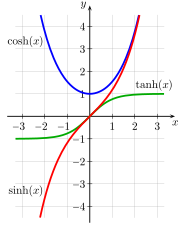

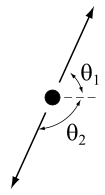

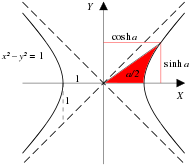

The natural functions for expressing these relationships are the hyperbolic analogs of the trigonometric functions. Fig. 4‑1a shows a unit circle with sin(a) and cos(a), the only difference between this diagram and the familiar unit circle of elementary trigonometry being that a is interpreted, not as the angle between the ray and the x-axis, but as twice the area of the sector swept out by the ray from the x-axis. (Numerically, the angle and 2 × area measures for the unit circle are identical.) Fig. 4‑1b shows a unit hyperbola with sinh(a) and cosh(a), where a is likewise interpreted as twice the tinted area.[40] Fig. 4‑2 presents plots of the sinh, cosh, and tanh functions.

For the unit circle, the slope of the ray is given by

In the Cartesian plane, rotation of point (x, y) into point (x', y') by angle θ is given by

In a spacetime diagram, the velocity parameter is the analog of slope. The rapidity, φ, is defined by[30]: 96–99

where

The rapidity defined above is very useful in special relativity because many expressions take on a considerably simpler form when expressed in terms of it. For example, rapidity is simply additive in the collinear velocity-addition formula;[6]: 47–59

or in other words,

The Lorentz transformations take a simple form when expressed in terms of rapidity. The γ factor can be written as

Transformations describing relative motion with uniform velocity and without rotation of the space coordinate axes are called boosts.

Substituting γ and γβ into the transformations as previously presented and rewriting in matrix form, the Lorentz boost in the x direction may be written as

and the inverse Lorentz boost in the x direction may be written as

In other words, Lorentz boosts represent hyperbolic rotations in Minkowski spacetime.[30]: 96–99

The advantages of using hyperbolic functions are such that some textbooks such as the classic ones by Taylor and Wheeler introduce their use at a very early stage.[6][41] [note 9]

4‑vectors

Click here for a brief section summary

Four‑vectors have been mentioned above in context of the energy-momentum 4‑vector, but without any great emphasis. Indeed, none of the elementary derivations of special relativity require them. But once understood, 4‑vectors, and more generally tensors, greatly simplify the mathematics and conceptual understanding of special relativity. Working exclusively with such objects leads to formulas that are manifestly relativistically invariant, which is a considerable advantage in non-trivial contexts. For instance, demonstrating relativistic invariance of Maxwell's equations in their usual form is not trivial, while it is merely a routine calculation (really no more than an observation) using the field strength tensor formulation. On the other hand, general relativity, from the outset, relies heavily on 4‑vectors, and more generally tensors, representing physically relevant entities. Relating these via equations that do not rely on specific coordinates requires tensors, capable of connecting such 4‑vectors even within a curved spacetime, and not just within a flat one as in special relativity. The study of tensors is outside the scope of this article, which provides only a basic discussion of spacetime.

Definition of 4-vectors

A 4-tuple, A = (A0, A1, A2, A3) is a "4-vector" if its component A i transform between frames according the Lorentz transformation.

If using (ct, x, y, z) coordinates, A is a 4–vector if it transforms (in the x-direction) according to

which comes from simply replacing ct with A0 and x with A1 in the earlier presentation of the Lorentz transformation.

As usual, when we write x, t, etc. we generally mean Δx, Δt etc.

The last three components of a 4–vector must be a standard vector in three-dimensional space. Therefore a 4–vector must transform like (c Δt, Δx, Δy, Δz) under Lorentz transformations as well as rotations.[24]: 36–59

Properties of 4-vectors

- Closure under linear combination: If A and B are 4-vectors, then C = aA + aB is also a 4-vector.