Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (February 2018) |

| Volhynian massacre | |

|---|---|

Monument in memory of the Polish victims of Janowa Dolina, Volyn (Wołyń) | |

| Location | Volhynia Eastern Galicia Polesie Lublin region |

| Date | 1943–45 |

| Target | Poles |

Attack type | Ethnic Cleansing, Genocide |

| Deaths | 40,000- 60,000 in Volhynia and 30,000- 40,000 in Eastern Galicia |

| Perpetrators | Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, Ukrainian Insurgent Army, Mykola Lebed |

The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia (Template:Lang-pl, literally: Volhynian slaughter; Template:Lang-ua, Volyn tragedy), were part of an ethnic cleansing operation carried out in Nazi German-occupied Poland by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) in the area of Volhynia, Polesia, Lublin region and Eastern Galicia beginning in 1943 and lasting up to 1945.[1] The peak of the genocide took place in July and August 1943. Most of the victims were women and children.[2] UPA's methods were particularly brutal,[3][4] and resulted in 40,000–60,000 polish deaths in Volhynia and 30,000–40,000 in Eastern Galicia, with the other regions for the total about 100,000[5][6][7]

The killings were directly linked with the policies of the Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN-B) and its military arm, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, whose goal as specified at the Second Conference of the OUN-B on 17–23 February 1943 (or March 1943 according to other sources) was to purge all non-Ukrainians from the future Ukrainian state.[8] Not limiting their activities to the purging of Polish civilians, UPA also wanted to erase all traces of the Polish presence in the area.[9] The violence was endorsed by a significant number of the Ukrainian Orthodox clergy who supported UPA's nationalist cause.[10] The massacres led to a civil conflict between Polish and Ukrainian forces in the German-occupied territories, with the Polish Home Army in Volhynia[11] responding to the Ukrainian attacks.[12][13]

In 2008, the massacres committed by the Ukrainian nationalists against ethnic Poles in Volhynia and Galicia were described by Poland's Institute of National Remembrance as bearing the distinct characteristics of a genocide,[14][15] and on 22 July 2016, the Parliament of Poland passed a resolution recognizing the massacres as genocide.[16][17]

Background

The principalities of Galicia and Volhynia were formed in the 11th century as the disputed territories of the Polish-Rus border.[clarification needed] They became part of Poland in the 14th century, when the Polish king Casimir III the Great gained the Principality of Galicia–Volhynia from the defeated Mongols in 1349.[18] Polish-Ukrainian tensions date back to the Khmelnytsky Uprising of the 17th century, with territorial, religious, and social dimensions persisting in the national memories of both groups.[19] While relations were not always harmonious, Poles who lived in the Kresy region (which corresponds to modern day western Ukraine and western Belarus) and Ukrainians, along with Czechs, Germans, Slovaks, Jews, and other ethnic groups in the region interacted with each other on civic, economic, and political levels over several hundred years.

The two regions were inhabited by Poles and Ukrainians, along with Czech, Slovak and Armenian newcomers who were later polonised. In the 19th century, with the rise of nationalism across Europe, the ethnicity of citizens became an issue, and conflicts erupted anew after the First World War. Both Poles and Ukrainians claimed the territories of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. The political conflicts escalated in the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period, particularly in the 1930s as a result of a cycle of paramilitary activity by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, formed in Poland, and the subsequent state repressions.[20] In the summer of 1930 Ukrainian peasants set fire to 2,200 estates.[21] Collective punishment meted out by the state police afterwards further exacerbated animosity between Polish officials and the Ukrainian population.[21]

At the onset of World War II, with Soviet invasion and annexation of the area in 1939–1941 (see Polish September Campaign), militant Ukrainian nationalist extremists, distrustful of Polish territorial ambitions, saw an opportunity to cleanse Polish people from territory historically considered to be Ukrainian and to exact retribution for the Polonization which the re-established Polish state had inflicted upon the Ukrainians.[citation needed] Killings of Poles in Volhynia and Galicia started soon after the Soviet annexation of the territory, climaxing during the German occupation, and continuing after the Soviets re-occupied the Western Ukraine during the last year of the war.

Polish-Ukrainian relations after World War I

As the Austro-Hungarian government collapsed following World War I, Poles and Ukrainians struggled for control over the city, known as Lwów in Polish, Lviv in Ukrainian and Lemberg in German, which was populated mostly by Poles,[22] but surrounded by a Ukrainian majority in the villages and countryside.[23] The area belonged to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1772, but later, with the Partitions of Poland, was annexed to the Austrian empire. The conflict, known as the Polish–Ukrainian War, spilled over to Volhynia with the Ukrainian leader Symon Petliura attempting to expand Ukrainian claims westward. The war was conducted by professional forces on both sides, resulting in a relatively minimal number of civilian deaths. On July 17, 1919, a ceasefire was signed. On November 21, 1919, the Paris Peace Conference granted Eastern Galicia to Poland. The loss left a generation of frustrated western Ukrainian veterans convinced that Poland was Ukraine's principal enemy.[24]

Even though Polish statehood had just been re-established, over a century after the partitions, the frontiers between Poland and Soviet Russia had not been defined by the Treaty of Versailles. As a result, the Polish–Soviet War of 1920 broke out with the Soviets claiming both Ukraine and Belarus, which they viewed as a part of the former Russian Empire, currently undergoing civil war.[25] The Soviets forced Ukrainian forces to retreat to Podolia, and Petliura decided to ally with Poland's Józef Piłsudski. On April 21, 1920, Piłsudski and Petliura signed a military alliance accepting the Polish-Ukrainian border on the river Zbruch.[25] Following this agreement, the government of the West Ukrainian National Republic went into exile in Vienna,[26] viewing it as a betrayal. At the end of the war with the Soviets, the Peace of Riga was signed with Vladimir Lenin in 1921. Volhynia and Eastern Galicia were eventually annexed to the Second Polish Republic, while the rest of contemporary Ukraine, known as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, became part of the USSR. Meanwhile, the exiled Ukrainian government was disbanded on March 14, 1923, by the Council of Ambassadors at the League of Nations. After a long series of negotiations, the League of Nations decided that eastern Galicia would be incorporated into Poland, thus "taking into consideration that Poland has recognized that in regard to the eastern part of Galicia ethnographic conditions fully deserve its autonomous status."[27]

The rise of OUN

OUN-B

The decisions leading to the massacre of Poles in Volhynia and their implementation can be primarily attributed to the extremist Bandera faction of OUN (OUN-B) and not to other Ukrainian political or military groups.[28] The OUN-B's ideology involved the following ideas: integral nationalism, that a pure national state and language were desired goals;[29] glorification of violence and armed struggle of nation versus nation;[30] and totalitarianism, in which the nation must be ruled by one person and one political party. While the moderate Melnyk faction of OUN admired aspects of Mussolini's fascism, the more extreme Bandera faction of OUN admired aspects of Nazism.[31][32] At the time of OUN's founding, the most popular political party among Ukrainians was the Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance which, while opposed to Polish rule, called for peaceful and democratic means to achieve independence from Poland. The OUN, on the other hand, was originally a fringe movement within western Ukraine, condemned for its violence by figures from mainstream Ukrainian society such as the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytsky, who wrote of the OUN's leadership that "whoever demoralizes our youth is a criminal and an enemy of our people." [33] Several factors contributed to OUN-B's increase in popularity and, ultimately, monopoly of power within Ukrainian society, conditions necessary for the massacres to occur.

Interwar period in the Second Polish Republic

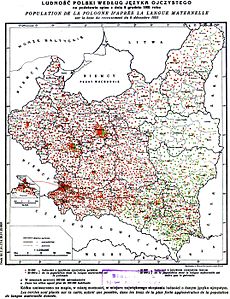

| Polish census of 1931 | |

|---|---|

| Original map showing the distribution of native languages spoken within Poland at the time of the 1931 census. | |

|

Just before the Soviet invasion of 1939, Volhynia was part of the Second Polish Republic. According to Yale historian Timothy Snyder, between 1928 and 1938, Volhynia was "the site of one of eastern Europe's most ambitious policies of toleration".[34] Through supporting Ukrainian culture, religious autonomy, and Ukrainization of the Orthodox church, Piłsudski and his allies wanted to achieve Ukrainian loyalty to the Polish state and to minimize Soviet influences in the borderline region. This approach was gradually abandoned after Piłsudski's death in 1935.[34][35]

Civil unrest in the Galician countryside resulted in Polish police exacting a policy of collective responsibility on local Ukrainians in an effort to "pacify" the region; demolishing Ukrainian community centers and libraries, confiscating property and produce, and beating protesters.[36] Ukrainian parliamentarians were placed under house arrest to prevent them from participating in elections, with their constituents terrorized into voting for Polish candidates.[36] The Ukrainian plight, protests, and pacification received the attention of the League of Nations as 'an international cause célèbre'; with Poland receiving condemnation from European politicians. The ongoing policies of the Polish state led to the deepening of ethnic cleavages in the area.[36]

In the 1930s OUN, formed in Vienna, Austria, conducted a terrorist campaign in Poland, which included the assassination of prominent Polish politicians such as Interior Minister Bronisław Pieracki, and Polish and Ukrainian moderates such as Tadeusz Hołówko.

Volhynia was a place of increasingly violent conflict, with Polish police on one side and West Ukrainian communists supported by many dissatisfied Ukrainian peasants on the other. The communists organized strikes, killed at least 31 suspected police informers in 1935–1936 and began to assassinate local Ukrainian officials for "collaboration" with the Polish state. The police conducted mass arrests, reported killing 18 communists in 1935, and killed at least 31 people in gunfights and during arrest actions over the course of 1936.[37]

Beginning in 1937, the Polish government in Volhynia initiated an active campaign to use religion as a tool for Polonization and to convert the Orthodox population to Roman Catholicism.[38] Over 190 Orthodox churches were destroyed and 150 converted to Roman Catholic churches.[39] Remaining Orthodox churches were forced to use the Polish language in their sermons. In August 1939, the last remaining Orthodox church in the Volhynian capital of Lutsk was converted to a Roman Catholic church by decree of the Polish government.[38]

Between 1921 and 1938, thousands of Polish colonists and war veterans were encouraged to settle in Volhynia and Galicia, in the areas lacking infrastructure; with no buildings, no roads, and no rail connections. In spite of great difficulties, their number reached 17,700 in Volhynia in 3,500 new settlements by 1939.[40] Ukrainian sources estimated the total number of Polish inhabitants in both Galicia and Volhynia at 300,000 including the 1930s settlers.[41] The short presence of the settlers, as all were forcibly expelled by the Soviets to Siberia, ignited further anti-Polish sentiment among the locals.[41][42]

Harsh policies implemented by the Second Polish Republic, while often provoked by OUN-B violence,[43][44] contributed to a further deterioration of relations between the two ethnic groups. Between 1934 and 1938, a series of violent and sometimes deadly[45] attacks against Ukrainians were conducted in other parts of Poland.[46]

Also in Wołyń Voivodeship some of the new policies were implemented, resulting in suppressing the Ukrainian language, culture and religion,[47] and the antagonism escalated.[48] Although around 68% of the voivodeship's population spoke Ukrainian as their first language (see table), practically all government and administrative positions, including the police, were assigned to Poles.[49]

Jeffrey Burds of Northeastern University believes that the buildup towards the ethnic cleansing of Poles that erupted during the Second World War in Galicia and Volhynia had its roots in this period.[46]

The Ukrainian population was outraged by the Polish government policies. A Polish report about the popular mood in Volhynia recorded a comment of a young Ukrainian from October 1938 as "we will decorate our pillars with you and our trees with your wives."[38]

By the beginning of World War II, the membership of OUN had risen to 20,000 active members and there were many times that number of supporters.[50]

Policies conducted by the Soviet Union (1939–1941)

In September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II and in accordance with the secret protocol of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was invaded from the west by Nazi Germany and from the east by the Soviet Union. Volhynia was split by the Soviets into two oblasts, Rovno and Volyn of the Ukrainian SSR. Upon the annexation, the Soviet NKVD started to eliminate the predominantly Polish middle and upper classes, including social activists and military leaders. Between 1939–1941, 200,000 Poles were deported to Siberia by the Soviet authorities.[51] Many Polish prisoners of war were deported to the East Ukraine where most of them were executed in basements of the Kharkiv NKVD offices.[52] Estimates of the number of Polish citizens transferred to the Eastern European part of the USSR, the Urals, and Siberia range from 1.2 to 1.7 million.[53] Tens of thousands of Poles fled from the Soviet-occupied zone to areas controlled by the Germans.[51] The deportations and murders deprived the Poles of their community leaders.

During the Soviet occupation, Polish members of the local administration were replaced by Ukrainians and Jews,[54] and the Soviet NKVD subverted the Ukrainian independence movement. All local Ukrainian political parties were abolished. Between 20,000 and 30,000 Ukrainian activists fled to German-occupied territory; most of those who did not escape were arrested. For example, Dr. Dmytro Levitsky, the head of the moderate, left-leaning democratic party Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance, and chief of the Ukrainian delegation in the pre-war Polish parliament, as well as many of his colleagues, were arrested, deported to Moscow, and never heard from again.[55] The elimination by the Soviets of the individuals, organizations, and parties that represented moderate or liberal political tendencies within Ukrainian society left the extremist Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which operated in the underground, as the only political party with a significant organizational presence among western Ukrainians.[56]

Policies conducted by Nazi Germany (1941–1943)

On June 22, 1941 the territories of eastern Poland occupied by the Soviet Union were attacked by German, Slovak, and Hungarian forces. The Red Army in Volhynia was able to resist only for a couple of days. On June 30, 1941 the Soviets withdrew eastward and Volhynia was overrun by the Nazis, with support from Ukrainian nationalists carrying out acts of sabotage. The OUN organized the Ukrainian People's Militia, which staged pogroms and assisted the Germans with roundups and executions of Poles, Jews, and those deemed as communist or Soviet activists,[57][58] most notably in the city of Lwów, Stanisławów, Korosten and Sokal among other locations.[59]

In 1941, two brothers of Ukrainian leader Stepan Bandera were murdered while imprisoned in Auschwitz by Volksdeutsche kapos.[60] In the Chełm region, 394 Ukrainian community leaders were killed by the Poles on the grounds of collaboration with the German authorities.[61]

During the first year of German occupation, OUN urged its members to join German police units. As police, they were trained in the use of weapons and as a result they could assist the German SS in murdering approximately 200,000 Volhynian Jews. While the Ukrainian police's share in the actual killings of Jews was small (they primarily played a supporting role), the Ukrainian police learned genocidal techniques from the Germans i.e., detailed advanced planning and careful site selection; the use of phony assurances to the local populace prior to annihilation; sudden encirclement; and mass killing. This training from 1942 explains UPA's efficiency in the killing of Poles in 1943.[62]

Ethnic cleansing

Prelude

Only one group of Ukrainian nationalists, OUN-B under Mykola Lebed and then Roman Shukhevych, intended to ethnically cleanse Volhynia of Poles. Taras Bulba-Borovets, the founder of the Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army, rejected this idea and condemned the anti-Polish massacres when they started.[63][64] The OUN-M leadership didn't believe that such an operation was advantageous in 1943.[65]

After Hitler's attack on the Soviet Union, both the Polish Government in Exile and the Ukrainian OUN-B considered the possibility that in the event of mutually exhaustive attrition warfare between Germany and the Soviet Union, the region would become a scene of conflict between Poles and Ukrainians. The Polish Government in Exile, which wanted the region returned to Poland, planned for a swift armed takeover of the territory as part of its overall plan for a future anti-Nazi uprising.[66] This view was compounded by OUN's prior collaboration with the Nazis, that by 1943 no understanding between the Polish government's Home Army and OUN was possible.[65] In Eastern Galicia, the antagonism between Poles and Ukrainians intensified under the German occupation.[67] Due to perceived Ukrainian collaboration with the Soviet government in 1939–1941 and with the later German administration, the general consensus among local Poles was that Ukrainians ought to be removed from these territories. In July 1942 a memorandum by the staff of the Home Army in Lviv in July 1942 recommended that between 1 million and 1.5 million Ukrainians be deported from Galicia and Volhynia to the Soviet Union and the rest scattered throughout Poland.[67][68] Suggestions of a limited Ukrainian autonomy, as was being discussed by the Home Army in Warsaw and the Polish Exile Government in London, would find no support among the local Polish population. At the beginning of 1943, the Polish underground came to contemplate the possibility of rapprochement with Ukrainians. This proved fruitless as neither side was willing to retreat from its claim to Lviv.[67]

Even before the war, OUN adhered to concepts of integral nationalism in its totalistic form, according to which Ukrainian statehood required ethnic homogeneity and the Polish enemy could be defeated only by the elimination of Poles from Ukrainian territories. From OUN-B perspective, the Jewish population had already been annihilated, Russians and Germans were only temporarily in Ukraine, but Poles had to be forcefully removed.[65] The OUN-B came to believe that it had to move fast while the Germans still controlled the area in order to preempt future Polish efforts at re-establishing Poland's pre-war borders. The result was that the local OUN-B commanders in Volhynia and Galicia (if not the OUN-B leadership itself) decided that an ethnic cleansing of Poles from the area, through terror and murder, was necessary.[65]

As evidenced by both Polish and Ukrainian underground reports, initially, the only major concern of Ukrainian nationalists was that of strong Soviet partisan groups operating in the area. The groups consisted mostly of Soviet POWs and initially specialized in raiding local settlements, which disturbed both the OUN and local Polish self-defense units, who expected it to result in an increase in German terror.[citation needed] These concerns soon materialized as Germans began "pacifying" entire villages in Volhynia in retaliation for real or alleged support for the Soviet partisans. Polish historiography attributed most of these actions to Ukrainian nationalists, while in reality they were conducted by Ukrainian auxiliary police units under the direct supervision of Germans.[citation needed] One of the best-known examples was the pacification of Obórki village in Lutsk county on November 13–14, 1942. While most of the actions were carried out by the Ukrainian occupational police, the murder of 53 Polish villagers was perpetrated personally by the Germans, who supervised the operation.[69][70]

For many months in 1942, the OUN-B was not able to control the situation in Volhynia, where in addition to Soviet partisans, many independent Ukrainian self-defense groups started to form in response to the growth of German terror. The first OUN-B military groups were created in Volhynia in autumn 1942 with the goal of subduing the other independent groups. By February 1943 OUN had initiated a policy of murdering civilian Poles as a way of resolving the Polish question in Ukraine. In spring 1943 OUN-B partisans started to call themselves the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), using the former name of the Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army, another Ukrainian group operating in the area in 1942. In March 1943 approximately 5,000 Ukrainian policemen defected with their weapons and joined UPA. Well-trained and well-armed, this group contributed to UPA achieving dominance over other Ukrainian groups active in Volhynia.[51] Soon, the newly created OUN-B forces managed to either destroy or absorb other Ukrainian groups in Volhynia, including four OUN-M units and the Ukrainian People's Revolutionary Army. According to Timothy Snyder, along the way Bandera-faction partisans killed tens of thousands of Ukrainians for supposed links to Melnyk or Bulba-Borovets.[63] The OUN-B undertook steps to liquidate "foreign elements", with posters and leaflets urging Ukrainians to murder Poles.[54] Its dominance secured (in spring 1943, UPA gained control over the Volhynian countryside from the Germans), UPA began large-scale UPA operations against the Polish population.[51][65]

Volhynia

Events

Between 1939 and 1943, Volhynian Poles had been already reduced to some 8% of the region's population (around 200,000 people). They were dispersed around the countryside, deprived of their elites by Soviet deportations, with neither local partisan army of their own nor state authority (except the Germans) to protect them.[71]

On February 9, 1943, a UPA group commanded by Hryhory Perehyniak, pretending to be Soviet partisans assaulted the Parośle settlement in Sarny county.[72][73][74] It is considered a prelude[75] to the massacres, and is recognized as the first[75] mass murder committed by UPA in the area. Estimates of the number of victims range from 149[76] to 173.[77]

In 1943 the massacres were organized westwards, starting in March in Kostopol and Sarny counties. In April they moved to the area of Krzemieniec, Rivne, Dubno and Lutsk.[78] Between late March and early April 1943, killing approximately 7,000 unarmed men, women, and children in its first days.[79]

On the night of April 22–23, Ukrainian groups, commanded by Ivan Lytwynchuk (aka Dubovy), attacked the settlement of Janowa Dolina, killing 600 people and burning down the entire village.[80] Those few who survived were mostly people that found refuge with friendly Ukrainian families.[81][better source needed] In one of the massacres, in the village of Lipniki, almost the entire family of Mirosław Hermaszewski (Poland's only astronaut) was murdered[82] along with about 180 inhabitants.[83] The attackers murdered the grandparents of composer Krzesimir Dębski, whose parents engaged during the Ukrainian attack on Kisielin.[84] Dębski's parents survived, taking refuge with a friendly Ukrainian family.

In another massacre, according to UPA reports, the Polish colonies of Kuty, in the Szumski region, and Nowa Nowica, in the Webski region, were liquidated for cooperation with the Gestapo and German authorities."[85] According to Polish sources, the Kuty self-defense unit managed to repel a UPA assault, though at least 53 Poles were murdered. The rest of the inhabitants decided to abandon the village and were escorted by the Germans who arrived at Kuty, alerted by the glow of fire and the sound of gunfire.[86] Maksym Skorupskyi, one of UPA commanders, wrote in his diary:"Starting from our action on Kuty, day by day after sunset, the sky was batching in the glow of conflagration. Polish villages were burning."[86]

By June 1943, the attacks had spread to the counties of Kowel, Włodzimierz Wołyński, and Horochów, and in August to Luboml county.[78] The Soviet victory at Kursk acted as a stimulus for escalation of massacres in June and August 1943, when ethnic cleansing reached its peak.[54] In June 1943, Dmytro Klyachkivsky head-commander of UPA-North issued a secret directive saying:

We should make a large action of the liquidation of the Polish element. As the German armies withdraw, we should take advantage of this convenient moment for liquidating the entire male population in the age from 16 up to 60 years. We cannot lose this fight, and it is necessary at all costs to weaken Polish forces. Villages and settlements lying next to the massive forests, should disappear from the face of the earth.[87][88]

Despite this, most of the victims were women and children.[2] In mid-1943, after a wave of killings of Polish civilians, the Poles tried to initiate negotiations with UPA. Two delegates of the Polish government in Exile and AK,[89] Zygmunt Rumel and Krzysztof Markiewicz attempted to negotiate with UPA leaders, but were captured and murdered on July 10, 1943, in the village of Kustycze.[90] Some sources claim they were tortured before their death.[91]

The following day, July 11, 1943, is regarded as the bloodiest day of the massacres, [92] with many reports of UPA units marching from village to village, killing Polish civilians.[93] On that day, UPA units surrounded and attacked Polish villages and settlements located in three counties – Kowel, Horochow, and Włodzimierz Wołyński. Events began at 3:00 am, leaving the Poles with little chance to escape. After the massacres, the Polish villages were burned to the ground. According to those few who survived, the action had been carefully prepared; a few days before the massacres there had been several meetings in Ukrainian villages, during which UPA members told the villagers that the slaughter of all Poles was necessary.[93] Altogether, on July 11, 1943, the Ukrainians attacked 167 towns and villages.[94] Within a few days an unspecified number of Polish villages were completely destroyed and their populations murdered. In the Polish village of Gurow, out of 480 inhabitants, only 70 survived; in the settlement of Orzeszyn, UPA killed 306 out of 340 Poles; in the village of Sadowa out of 600 Polish inhabitants only 20 survived; in Zagaje out of 350 Poles only a few survived.[93] This wave of massacres lasted 5 days, until July 16. UPA continued the ethnic cleansing, particularly in rural areas, until most Poles had been deported, killed or expelled. These actions were conducted by many units, and were well-coordinated and thoroughly planned.[54]

In August 1943, the Polish village of Gaj (near Kovel) was burned and some 600 people massacred, in the village of Wola Ostrowiecka 529 people were killed, including 220 children under 14, and 438 people were killed, including 246 children, in Ostrowki. In September 1992 exhumations were carried out in these villages, confirming the number of dead.[93]

In the same month UPA placed notices in every Polish village stating "in 48 hours leave beyond the Bug River or the San river- otherwise Death."[96] Ukrainian attackers limited their actions to villages and settlements, and did not strike towns or cities.

The killings were opposed by the Ukrainian Central Committee under Volodymyr Kubiyovych. In response, UPA units murdered Ukrainian Central Committee representatives, and murdered a Ukrainian Catholic priest who had read an appeal by the Ukrainian Central Committee from his pulpit.[97]

Polish historian Władysław Filar, who witnessed the massacres, cites numerous statements made by Ukrainian officers when reporting their actions to the leaders of UPA-OUN. For example, in late September 1943, the commandant "Lysyi" wrote to the OUN headquarters: "On September 29, 1943, I carried out the action in the villages of Wola Ostrowiecka (see Massacre of Wola Ostrowiecka), and Ostrivky (see Massacre of Ostrówki). I have liquidated all Poles, starting from the youngest ones. Afterwards, all buildings were burned and all goods were confiscated".[98] On that day in Wola Ostrowiecka 529 Poles were murdered (including 220 children under 14), and in Ostrówki, the Ukrainians killed 438 persons (including 246 children).[99]

Methods

The atrocities were carried out indiscriminately and without restraint. The victims, regardless of their age or gender, were routinely tortured to death. Norman Davies in No Simple Victory gives a short, but shocking description of the massacres. He writes:

Villages were torched. Roman Catholic priests were axed or crucified. Churches were burned with all their parishioners. Isolated farms were attacked by gangs carrying pitchforks and kitchen knives. Throats were cut. Pregnant women were bayoneted. Children were cut in two. Men were ambushed in the field and led away. The perpetrators could not determine the province's future. But at least they could determine that it would be a future without Poles.[100]

An OUN order from early 1944 stated:

Liquidate all Polish traces. Destroy all walls in the Catholic Church and other Polish prayer houses. Destroy orchards and trees in the courtyards so that there will be no trace that someone lived there... Pay attention to the fact that when something remains that is Polish, then the Poles will have pretensions to our land".[9]

UPA commander's order of 6 April 1944 stated: "Fight them [the Poles] unmercifully. No one is to be spared, even in case of mixed marriages"[101]

Timothy Snyder describes the murders: "Ukrainian partisans burned homes, shot or forced back inside those who tried to flee, and used sickles and pitchforks to kill those they captured outside. In some cases, beheaded, crucified, dismembered, or disemboweled bodies were displayed, in order to encourage remaining Poles to flee".[51] A similar account has been presented by Niall Ferguson, who wrote: "Whole villages were wiped out, men beaten to death, women raped and mutilated, babies bayoneted."[102] Ukrainian historian Yuryi Kirichuk described the conflict as similar to medieval rebellions.[103]

According to Polish historian Piotr Łossowski, the method used in most of the attacks was the same. At first, local Poles were assured that nothing would happen to them. Then, at dawn, a village was surrounded by armed members of UPA, behind whom were peasants with axes, hammers, knives, and saws. All the Poles encountered were murdered; sometimes they were herded into one spot, to make it easier. After a massacre, all goods were looted, including clothes, grain, and furniture. The final part of an attack was setting fire to the village.[104] In many cases, victims were tortured and their bodies mutilated. All vestiges of Polish existence eradicated with even abandoned Polish settlements burned to the ground.[54]

Even though it may be an exaggeration to say that the massacres enjoyed general support of the Ukrainians, it has been suggested that without wide support from local Ukrainians they would have been impossible.[51] Those Ukrainian peasants who took part in the killings created their own groups called SKV or Samoboronni Kushtchovi Viddily (Самооборонні Кущові Відділи, СКВ). Many of their victims perceived as Poles even without the knowledge of the Polish language, were murdered by СКВ along with the others.[105]

Ukrainians in ethnically mixed settlements were offered material incentives to join in the slaughter of their neighbours, or warned by UPA's security service (Sluzhba Bezbeky) to flee by night, while all remaining inhabitants were murdered at dawn. Many Ukrainians risked, and in some cases, lost their lives trying to shelter or warn Poles[51][106] – such activities were treated by UPA as collaboration with the enemy and severely punished.[107] In 2007, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) published a document Kresowa Ksiega Sprawiedliwych 1939 – 1945. O Ukraincach ratujacych Polakow poddanych eksterminacji przez OUN i UPA ("Borderland's Book of the Righteous. About Ukrainians saving Poles from extermination of OUN and UIA"). The author of the book, IPN's historian Romuald Niedzielko, documented 1341 cases in which Ukrainian civilians helped their Polish neighbors. For this, 384 Ukrainians were executed by UPA.[108] In case of Polish-Ukrainian families, one common UPA instruction was to kill one's Polish spouse and children born of that marriage. People who refused to carry such order were often murdered together with their entire family.[42][109]

Self-defence organizations

The massacres prompted Poles, starting in April 1943, to organize self-defence organizations, 100 of which were formed in Volhynia in 1943. Sometimes these self-defence organization obtained arms from the Germans; other times the Germans confiscated their weapons and arrested the leaders. Many of these organizations could not withstand the pressure of UPA and were destroyed. Only the largest self-defense organizations who were able to obtain help from the AK or from Soviet partisans were able to survive.[110] Kazimierz Bąbiński, commander of the Union for Armed Struggle-Home Army Wołyń in his order to AK partisan units stated[111]

I forbid the use of the methods utilized by the Ukrainian butchers. We will not burn Ukrainian homesteads nor kill Ukrainian women and children in retaliation. The self-defence network must protect itself from the aggressors or attack the agressors but leave the peaceful population and their possessions alone.

— "Luboń"

The AK on 20 July 1943 called upon Polish self-defense units to place themselves under its command. Ten days later, it declared itself in favor of Ukrainian independence on territories without Polish populations, and called for an end to the killings of civilians.[112] Polish self-defense organizations took part in revenge massacres of Ukrainian civilians starting in the summer of 1943, when Ukrainian villagers who had nothing to do with the massacres suffered at the hands of Polish partisan forces. Evidence includes a letter dated 26 August 1943 to local Polish self-defense where AK commander Kazimierz Bąbiński criticized the burning of neighboring Ukrainian villages, killing any Ukrainian that crosses their path, and robbing Ukrainians of their material possessions.[113] The total number of Ukrainian civilians murdered in Volyn in retaliatory acts by Poles is estimated at 2,000–3,000.[114] The 27th Home Army Infantry Division was formed in January 1944, and tasked to fight UPA and then the Wehrmacht.[112]

Death toll

According to Ukrainian sources, in October 1943 the Volhynian delegation of the Polish government estimated the number of Polish casualties in the counties of Sarny, Kostopol, Równe, and Zdołbunów, to exceed 15,000 people.[115] Timothy Snyder estimates that in July 1943 UPA actions resulted in the deaths of at least 40,000 Polish civilians in Volhynia (in March 1944 another 10,000 in Galicia)[116], causing additional 200,000 Poles to flee west before September 1944, and 800,000 after that.[51][116]

Eastern Galicia

In late 1943 and early 1944, after most Poles in Volhynia had either been murdered or had fled the area, the conflict spread to the neighboring province of Galicia, where the majority of the population was still Ukrainian, but where the Polish presence was strong. Unlike in the case of Volhynia, where Polish villages were usually destroyed and their inhabitants murdered without warning, in east Galicia Poles were sometimes given the choice of fleeing or being killed. An order by an UPA commander in Galicia stated, "Once more I remind you: first call upon Poles to abandon their land and only later liquidate them, not the other way around"). This change in tactics, combined with better Polish self-defense and a demographic balance more favorable to Poles, resulted in a significantly lower death toll among Poles in Galicia than in Volhynia.[117] The methods used by Ukrainian nationalists in this area were the same, and consisted of rounding up and killing all the Polish residents of the villages, then looting the villages and burning them to the ground.[54] On February 28, 1944, in the village of Korosciatyn 135 Poles were murdered;[118] the victims were later counted by a local Roman Catholic priest, Rev. Mieczysław Kamiński.[119] Jan Zaleski (father of Fr. Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski) who witnessed the massacre, wrote in his diary: "The slaughter lasted almost all night. We heard terrible cries, the roar of cattle burning alive, shooting. It seemed that Antichrist himself began his activity!"[120] Father Kamiński claimed that in Koropiec, where no Poles were actually murdered, a local Greek Catholic priest, in reference to mixed Polish-Ukrainian families, proclaimed from the pulpit: "Mother, you're suckling an enemy – strangle it." [121] Among the scores of Polish villages whose inhabitants were murdered and all buildings burned, there are such places as Berezowica near Zbaraz, Ihrowica near Ternopil, Plotych near Ternopil, Podkamien near Brody, and Hanachiv and Hanachivka near Przemyślany.[122]

Roman Shukhevych, UPA commander, stated in his order from 25 February 1944: "In view of the success of the Soviet forces it is necessary to speed up the liquidation of the Poles, they must be totally wiped out, their villages burned ... only the Polish population must be destroyed."[42]

One of the most infamous massacres took place on February 28, 1944, in the Polish village of Huta Pieniacka, with over 1,000 inhabitants. The village served as a shelter for refugees including Polish Jews,[123] as well as a recuperation base for Polish and Communist partisans. One AK unit was active there. In the winter of 1944 a Soviet partisan unit numbering 1,000 was stationed in the village for two weeks.[123][124][125] Huta Pieniacka's villagers, although poor, organized a well-fortified and armed self-defense unit that fought off a Ukrainian and German reconnaissance attack on February 23, 1944.[126] Two soldiers of the 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Galicia (1st Ukrainian) Division of the Waffen-SS were killed and one wounded by the villagers. On February 28, elements of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division from Brody returned with 500–600 men, assisted by a group of civilian nationalists. The killing spree lasted all day. Kazimierz Wojciechowski, the commander of the Polish self-defense unit, was drenched with gasoline and burned alive at the main square. The village was utterly destroyed and all of its occupants killed.[124] The civilians, mostly women and children, were rounded up at a church, divided and locked in barns which were set on fire.[127] Estimates of casualties in the Huta Pieniacka massacre vary, and include 500 (Ukrainian archives),[128] over 1,000 (Tadeusz Piotrowski),[129] and 1,200 (Sol Littman).[130] According to IPN investigation, the crime was committed by the 4th battalion of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division[127] supported by UPA units and local Ukrainian civilians.[131]

A military journal of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division condemned the killing of Poles. In a March 2, 1944 article directed to the Ukrainian youth, written by military leaders, Soviet partisans were blamed for the murders of Poles and Ukrainians, and the authors stated that "If God forbid, among those who committed such inhuman acts, a Ukrainian hand was found, it will be forever excluded from the Ukrainian national community."[132] Some historians deny the role of the Ukrainian 14th SS Division in the killings, and attribute them entirely to German units, while others disagree.[133][verification needed] According to Yale historian Timothy Snyder, the Ukrainian 14th SS Division's role in the ethnic cleansing of Poles from western Ukraine was marginal.[134]

The village of Pidkamin (Podkamień) near Brody was a shelter for Poles, who hid in the monastery of the Dominicans there. Some 2,000 persons, the majority of them women and children, were living there when the monastery was attacked in mid-March 1944 by UPA units, which according to Polish Home Army accounts were cooperating with the Ukrainian SS. Over 250 Poles were killed.[123] In the nearby village of Palikrovy, 300 Poles were killed, 20 in Maliniska and 16 in Chernytsia. Armed Ukrainian groups destroyed the monastery, stealing all valuables. What remained was the painting of Mary of Pidkamin, which now is kept in St. Wojciech Church in Wrocław. According to Kirichuk, the first attacks on the Poles took place there in August 1943 and they were probably the work of UPA units from Volhynia. In retaliation, Poles killed important Ukrainians, including the Ukrainian doctor Lastowiecky from Lviv and a popular football player from Przemyśl, Wowczyszyn.

By the end of the summer, mass acts of terror aimed at Poles were taking place in Eastern Galicia with the purpose of forcing Poles to settle on the western bank of the San River, under the slogan "Poles behind the San". Snyder estimates that 25,000 Poles were killed in Galicia alone,[135] Grzegorz Motyka estimated the number of victims at 30,000–40,000.[136]

The slaughter did not stop after the Red Army entered the areas, with massacres taking place in 1945 in such places as Czerwonogrod (Ukrainian: Irkiv), where 60 Poles were murdered on February 2, 1945,[137][138] the day before they were scheduled to depart for the Recovered Territories.

By Autumn 1944 anti-Polish actions stopped and terror was used only against those who co-operated with the NKVD, but in late 1944 and in the beginning of 1945 UPA performed a last massive anti-Polish action in Ternopil region.[139] On the night of February 5–6, 1945, Ukrainian groups attacked the Polish village of Barysz, near Buchach: 126 Poles were massacred, including women and children. A few days later on February 12–13, a local group of OUN under Petro Khamchuk attacked the Polish settlement of Puźniki, killing around 100 people and burning houses. Those who survived moved mostly to Niemysłowice, Gmina Prudnik.[140]

Approximately 150[141]-366 Ukrainian and a few Polish inhabitants of Pawłokoma were killed on March 3, 1945 by a former Polish Home Army unit aided by Polish self-defense groups from nearby villages. The massacre is believed to be an act of retaliation for earlier alleged murders by Ukrainian Insurgent Army of nine (or 11) Poles [142] in Pawłokoma and unspecified number of Poles killed by UPA in neighboring villages.

German involvement

While Germans actively encouraged the conflict, for most of the time they attempted to not get directly involved. Special German units formed from collaborationist Ukrainian, and later Polish auxiliary police were deployed in pacification actions in Volhynia, and some of their crimes were attributed to either the Polish Home Army or the Ukrainian UPA.

According to Yuriy Kirichuk the Germans were actively prodding both sides of the conflict against each other.[143] Erich Koch once said: "We have to do everything possible so that a Pole meeting a Ukrainian, would be willing to kill him and conversely, a Ukrainian would be willing to kill a Pole". Kirichuk quotes a German commissioner from Sarny whose response to Polish complaints was: "You want Sikorski, the Ukrainians want Bandera. Fight each other".[143]

The Nazis replaced Ukrainian policemen who deserted from German service with Polish policemen. Polish motives for joining were local and personal: to defend themselves or avenge UPA atrocities.[144] German policy called for the murder of the family of every Ukrainian police officer who deserted and the destruction of the village of any Ukrainian police officer deserting with his weapons. These retaliations were carried out using newly recruited Polish policemen. Though Volhynian Polish participation in the German Police followed UPA attacks on Polish settlements, it provided the Ukrainian Nationalists with useful sources of propaganda and was used as a justification for the cleansing action. OUN-B leader summarized the situation in August 1943 by saying that the German administration "uses Polaks in its destructive actions. In response we destroy them unmercifully."[85] Despite the desertions in March and April 1943, the auxiliary Police remained heavily Ukrainian, and Ukrainians serving the Nazis continued pacifications of Polish and other villages.[145]

On August 25, 1943, the German authorities ordered all Poles to leave the villages and settlements and move to larger towns.[citation needed]

Soviet partisan units present in the area were aware of the massacres. On May 25, 1943, the commander of the Soviet partisan forces of the Rivne area stressed in his report to the headquarters that Ukrainian nationalists did not shoot the Poles but cut them dead with knives and axes, with no consideration for age or gender.[146]

Number of victims

Polish casualties

The death toll among civilians murdered during the Volhynia Massacre is still being researched. At least 10% of ethnic Poles in Volhynia were killed during this time by UPA. Accordingly, "Polish casualties comprised about 1% of the prewar population of Poles on territories where UPA was active and 0.2% of the entire ethnically Polish population in Ukraine and Poland."[147] Łossowski emphasizes that documentation is far from conclusive, as in numerous cases there were no survivors who would later be able to testify.[citation needed]

The Soviet and Nazi invasions of pre-war eastern Poland, UPA massacres, and postwar Soviet expulsions of Poles all contributed to the virtual elimination of a Polish presence in the region. Those who remained left Volhynia mostly for the neighbouring province of Lublin. After the war, the survivors moved further west to the territories of Lower Silesia. Polish orphans from Volhynia were kept in several orphanages, with the largest of them around Kraków. Several former Polish villages in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia do not exist any more and those that remain are in ruins.

The Institute of National Remembrance estimates that 100,000 Poles were killed by the Ukrainian nationalists (40,000–60,000 victims in Volhynia, 30,000−40,000 in Eastern Galicia, and at least 4,000 in Lesser Poland, including up to 2,000 in the Chełm region).[5] For Eastern Galicia, other estimates range between 20,000–25,000,[148] 25,000[23] and 30,000–40,000.[136] Niall Ferguson estimated the total number of Polish victims in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia to be between 60,000 and 80,000,[149] G. Rossolinski-Liebe: 70,000–100,000,[150] John P. Himka: 100,000.[7] According to Motyka, from 1943 to 1947 in all territories that were covered by the conflict, approximately 80,000–100,000 Poles were killed.[114] According to Ivan Katchanovski, a Ukrainian historian, between 35,000-60,000; with "the lower bound of these estimates [35,000] is more reliable than higher estimates which are based on an assumption that the Polish population in the region was several times less likely to perish as a result of Nazi genocidal policies compared to other regions of Poland and compared to the Ukrainian population of Volhynia."[147] Władysław Siemaszko and his daughter Ewa have documented 33,454 Polish victims, 18,208 of which are known by surname.[151] (in July 2010 Ewa Siemaszko increased the accounts to 38,600 documented victims, 22,113 of which are known by surname[152]). At the first ever joint Polish-Ukrainian conference in Podkowa Leśna organized on June 7–9, 1994 by Karta Centre and subsequent Polish-Ukrainian historian meetings, with almost 50 Polish and Ukrainian participants, an estimate of 50,000 Polish deaths in Volhynia was settled [153] which they considered to be moderate.[154][self-published source?] According to the sociologist Piotrowski, UPA actions resulted in an estimated number of 68,700 deaths in Wołyń Voivodeship.[155] Per Anders Rudling states that UPA killed 40,000–70,000 Poles in this area.[42] Some extreme estimates place the number of Polish victims as high as 300,000.[156][verification needed] Also, the numbers include polonized Armenians killed in the massacres, e.g. in Kuty [157]

Ukrainian casualties

Ukrainian casualties at the hands of Poles are estimated at 2,000–3,000 in Volhynia.[42] Together with those killed in other areas, the number of Ukrainian casualties were between 10,000 and 12,000,[5] with the bulk of them occurring in Eastern Galicia and present-day Poland. According to Kataryna Wolczuk for all areas affected by conflict, the Ukrainian casualties are estimated as from 10,000 to 30,000 between 1943 and 1947.[158] According to Motyka, author of a fundamental monograph about UPA,[159] estimations of 30,000 Ukrainian casualties are unsupported.[160]

Timothy Snyder states that it is likely UPA killed as many Ukrainians as it did Poles, as local Ukrainians who did not adhere to OUN's form of nationalism were regarded as traitors.[2] Within a month of the beginning of the massacres, Polish self-defense units responded in kind; all conflicts resulted in Poles taking revenge on Ukrainian civilians.[2] According to Motyka, the number of Ukrainian victims is between 2,000–3,000 in Volhynia and between 10,000–15,000 in all territories covered by the conflict.[6] G. Rossolinski-Liebe puts the number of Ukrainians (both OUN-UPA members and civilians) killed by Poles during and after the World War at 10,000–20,000.[150]

On 4 July 2016 a group of 45 active and former politicians, including former presidents Lech Walesa, Aleksander Kwasniewski, and Bronislaw Komorowski, issued a letter to Ukraine asking for forgiveness for the harm caused by Poles in the conflict.[161] The letter was in response to a similar statement issued one month prior by various political actors in Ukraine, including former presidents Leonid Kravchuk and Viktor Yushchenko.[162]

Table

| = Historian | = Political science | = Research group |

| Author | Volhynia | Galicia | VOL+GAL | V+G+P | E. POL | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timothy Snyder | 50k | – | – | – | In Past and Present | ||

| Timothy Snyder | >40k | 10k | – | – | [163] | 10k is in March '44, >40k in July '43 | |

| Timothy Snyder | 40-60k in '43 | 25k | – | 5k | The Reconstruction of Nations, 2004 | 5k is Lublin and Rzeszów; "killed by UPA"; "limited the death toll of Polish civilians to about twenty-five thousand in Galicia" | |

| Timothy Snyder | 5–10k | – | – | – | [51] | "Polish preparations and Ukrainian warnings limited the deaths to perhaps 5,000-10,000" | |

| Grzegorz Motyka | 40-60k | – | - | 80-100k | 6-8k | W kręgu Łun w Bieszczadach, 2009, page 13 | net is from '43 to '47 |

| Grzegorz Motyka | 40-60k | 30-40k | – | 100k | Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji "Wisła", 2011, pages 447–448 | ||

| Ivan Katchanovski | 35-60k | – | – | – | Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine | Katchanovski considers the lower bound 35k to be more likely; cited Snyder, Hrytsiuk | |

| Grzegorz Hryciuk | 35-60k | – | – | – | "Vtraty naselennia na Volyni u 1941-1944rr." Ukraina-Polshcha: Vazhki Pytannia, Vol. 5. Warsaw: Tyrsa, 2001 | Cited by Katchanovski | |

| Grzegorz Hryciuk | 35.7-60k | – | – | – | Hryciuk G. Przemiany narodowosciowe i ludnosciowe w Galicji Wschodniej i na Wolyniu w latach 1931–1948 / G. Hryciuk. – Torun, 2005. – S. 279. | Cited by Kalischuk | |

| Grzegorz Hryciuk | – | 20–24 | – | – | Straty ludnosci w Galicji Wschodniej w latach 1941–1945 / G. Hryciuk // Polska–Ukraina: trudne pytania. – Warszawa, 2000. – T. 6. – S. 279, 290, 294. | Cited by Kalischuk; from 43–46; 8820 in '43-mid'44; "according to relevant contemporary Polish sources" | |

| Grzegorz Hryciuk | 35.7-60k | 20-25k | – | G.Hryciuk, Przemiany narodowosciowe i ludnosciowe w Galicji Wschodniej i na Wolyniu w latach 1931–1948, Toruń 2005, pp. 279,315 | for Galicia "primary balance" relied on "fragmentary and often incomplete documentation" and witnesses' testimonies | ||

| P.R. Magocsi | – | – | – | 50k | Magocsi; A History of Ukraine, p 681 | "among the more reasonable estimates" | |

| Niall Ferguson | – | – | 60-80k | - | The war of the world, 2007[citation needed] | Fergusson is citing other authors (which ones?) | |

| John Paul Himka | – | – | 100k | - | Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history, 2001 | [5] | |

| Per Anders Rudling | 40-70k | – | - | 7k | Theory and Practice, 2006 | below note | |

| Rossolinski-Liebe | - | – | 70-100k | - | The Ukrainian national revolution (2011), Celebrating Fascism... (2010) | [6] (?) | |

| Ewa Siemaszko | 60k | 70k | 130k | 133k | Bilans zbrodni, 2010 [7] | According to Rudling it is the most extensive study of the Polish casualties (Rudling, "The OUN, the UPA and the Holocaust...", p. 50) | |

| Marek Jasiak | – | – | – | 60-70k | Redrawing Nations, p174 | "In Podole, Volhynia, and Lublin" | |

| Terles | 50k | 60-70k | – | 100-200k | In Ethnic Cleansing p. 61 | ||

| Karta | 35k | 29.8k | – | – | 6.5k | "Polska-Ukraina", t.7, 2000, p. 159, cited by Kalishchuk: here [8] | Karta based mostly on: Siemaszko for Volhynia (documented number) and Cz.Blicharski for Tarnopol voivodsh. |

| Katarina Wolczuk | – | - | – | 60-100k | "The Difficulties of Polish–Ukrainian Historical Reconciliation," paper published by the Royal Institute of International Affairs, London, 2002, cited by Marples | ||

| Alexander Gogun | 25k+ | – | – | Lib.OUN-UPA.org.ua [164] | Potsdam | ||

| Common communicate of PL and UKR historians | 50-60k | 20-25k | – | 5-6k | "Polska-Ukraina: trudne pytania", 2000, t. 9, p. 403. | "Polish casualties acc. to Polish sources" | |

| Ryszard Torzecki | 30-40k | 30-40k | 80-100k | 10-20k (Polesie and Lublin) | R. Torzecki, Polacy i Ukraińcy. Sprawa ukraińska podczas II wojny światowej na terenie II Rzeczypospolitej, 1993, p. 267 | ||

| IPN | 60-80k | – | – | – | Oddziałowa Komisja w Lublinie, January 2012 | killed by Ukrainian nationalists, 1939–1945? | |

| Norman Davies | – | – | - | hundreds of thousands | 'God's playground. A history of Poland', Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 350 | ethnic cleansing | |

| Czesław Partacz | – | – | – | 134-200k | Przemilczane w ukraińskiej historiografii przyczyny ludobójstwa popełnionego przez OUN-UPA na ludności polskiej [in:] Prawda historyczna na prawda polityczna w badaniach naukowych. Przykład ludobójstwa na Kresach Południowo-Wschodniej Polski w latach 1939–1946, Bogusław Paź (edition), Wrocław 2011 | ||

| Lucyna Kulińska | – | – | – | 150-200k | "Dzieci Kresów III", Kraków 2009, p. 467 | ||

| Anna M. Cienciala | - | - | 40-60k | The Rebirth of Poland. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004 | During WWII, the Bandera faction of the Ukrainian Insurrectionary Army (UPA) murdered 40,000–60,000 Poles living in the villages of former Volhynia and former East Galicia | ||

| Pertti Ahonen et al. | - | - | 100,000 | Pertti Ahonen, Gustavo Corni, Jerzy Kochanowski, Rainer Schulze, Tamás Stark, Barbara Stelzl-Marx, People on the Move: Population Transfers and Ethnic Cleansing Policies During World War II and Its Aftermath. Berg Publishers. 2008. p. 99. "100,000 killed & 300,000 refugees in ethnic cleansing conducted by Ukrainian nationalists" | |||

| George Liber | 25–70k | 20–70k | 50–100k | – | Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954 | 1943-44, "between 50,000 and 100,000 Poles" |

| Author | Volhynia | Galicia | VOL+GAL | V+G+P | E. POL | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grzegorz Motyka | 2-3k | – | - | 10-20k | 8-12k | W kregu łun w Bieszczadach, Rytm 2009, page 13 | 1943–1947, The number for total includes those killed in Volhynia, Galicia, territories of present-day (eastern) Poland |

| Grzegorz Motyka | 2-3k | 1-2k | - | 10/11-15k | 8-10k | Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji "Wisła", 2011, page 448 | 1943–1947; According to Motyka, numbers of Ukrainian casualties from hands of Poles >= 30k are "simply pulled out of thin air". |

| P.A. Rudling | 20k | – | 11k | in "Historical Representation of the Wartime Accounts of the Activities of the OUN..." | citation: "Most mainstream estimates" "growing consensus, is [...] up to 20,000 Ukrainians killed by AK in Volhynia." | ||

| P. R. Magocsi | – | – | 20k | Magocsi; A History of Ukraine, p 681 | "among the more reasonable estimates" | ||

| T. Snyder | 10k | – | – | Past and Present [citation needed] | "Over the course of 1943, perhabs ten thousand Ukrainian civilians were killed by Polish self-defence units, Soviet partisans, Nazi policemen". | ||

| T. Snyder | – | – | - | +5k | The reconstruction of nations[citation needed] | in Lublin and Rzeszów | |

| Rossolinski-Liebe | - | – | 10-20k | Celebrating Fascism... [citation needed] | both UPA members and civilians, during and after the war. Rossolinski cites Motyka's estimation of 2006. | ||

| Katarina Wolczuk | – | - | 15-30k | UK scholar. Cited by Marples. | |||

| Katrina Witt | – | – | 15-30k | Ukrainian Memory and Victimhood, p101 | Cited Marples, who cites Wolczuk. | ||

| Karta | unknown | unknown | – | 7.5k | "Polska-Ukraina", t.7, 2000, p. 159, cited by Kalishchuk: here [9] | ||

| Zashkilniak L. and M. Krykun | – | – | 35k | Zashkilniak L., M. Krykun History of Poland: from ancient times to the present day / L. Over- Shkilnyak – Lviv, 2002. – p. 527 | Cited by Kalishchuk. | ||

| Alexander Gogun | 10k+ | – | – | Lib.OUN-UPA.org.ua [164] | Potsdam | ||

| Anna M. Cienciala | - | - | - | 20k | - | The Rebirth of Poland. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004 | ...the Poles killed some 20,000 Ukrainians, mostly in former East Galicia in reprisal. |

| George Liber | 2–20k | 1–4k | 8–20k | – | Total Wars and the Making of Modern Ukraine, 1914-1954 | 1943-44, "and 8,000 to 20,000 Ukrainians died" |

Responsibility

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), of which the Ukrainian Insurgent Army would have become the armed wing, promoted removal, by force if necessary, of non-Ukrainians from the social and economic spheres of a future Ukrainian state.[165]

The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists adopted in 1929 the Ten Commandments of the Ukrainian Nationalists, which all members of the Organization were expected to adhere to. This Decalogue stated "Do not hesitate to carry out the most dangerous deeds" and "Treat the enemies of your nation with hatred and ruthlessness".[166]

The decision to ethnically cleanse the area East of Bug River was taken by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army early in 1943. In March 1943, OUN(B) (specifically Mykola Lebed[167]) imposed a collective death sentence of all Poles living in the former eastern part of the Second Polish Republic and a few months later local units of UPA were instructed to complete the operation with haste.[168] The decision to cleanse the territory of its Polish population determined the course of events in the future. According to Timothy Snyder, the ethnic cleansing of the Poles was exclusively the work of the extreme Bandera faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, rather than the Melnyk faction of that organization or other Ukrainian political or religious organizations. Polish investigators claim that the OUN-B central leadership decided in February 1943 to drive all Poles out of Volhynia, to obtain an "ethnically pure territory" in the postwar period. Among those who were behind the decision, Polish investigators single out Dmytro Klyachkivsky, Vasyl Ivakhov, Ivan Lytvynchuk, and Petro Oliynyk.[169]

Ethnic violence was exacerbated with the circulation of posters and leaflets inciting the Ukrainian population to murder Poles and "Judeo-Muscovites" alike.[170][171][172]

According to prosecutor Piotr Zając, Polish Institute of National Remembrance in 2003 considered three different versions of the events in its investigation:[173]

- the Ukrainians at first planned to chase the Poles out but the events got out of hand in the course of time.

- the decision to exterminate the Poles was taken by the OUN-UPA headquarters.

- the decision to exterminate the Poles was taken by some of the leaders of OUN-UPA in the course of an internal conflict within the organisation.

IPN concluded that the second version was the most likely one.[citation needed]

Reconciliation

The question of official acknowledgment of the ethnic cleansing remains a matter of a discussion between Polish and Ukrainian historians and political leaders. Efforts are ongoing to bring about reconciliation between Poles and Ukrainians regarding the events. The Polish side has made steps towards reconciliation. In 2002 president Aleksander Kwaśniewski expressed regret over the resettlement program, known as Operation Vistula, stating that "The infamous Operation Vistula is a symbol of the abominable deeds perpetrated by the communist authorities against Polish citizens of Ukrainian origin." He states that the argument that "Operation Vistula was the revenge for the slaughter of Poles by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army" in 1943–1944, was "fallacious and ethically inadmissible," as it invoked "the principle of collective guilt." [174] The Ukrainian government has not yet issued an apology.[175][176] On July 11, 2003, presidents Aleksander Kwaśniewski and Leonid Kuchma attended a ceremony held in the Volhynian village of Pavlivka (previously known as Poryck),[177] where they unveiled a monument to the reconciliation. The Polish President said that it is unjust to blame the entire Ukrainian nation for these acts of terror, saying "The Ukrainian nation cannot be blamed for the massacre perpetrated on the Polish population. There are no nations that are guilty... It is always specific people who bear the responsibility for crimes".[178]

Question of genocide

The question of whether this event should be characterized as 'genocide' or 'ethnic cleansing' is debated. Historian Per Anders Rudling states that the goal of OUN-UPA was not to exterminate all Poles, but rather to ethnically cleanse the region in order to attain an ethnically homogenous sate." The goal was thus to prevent a repeat of 1918-20 when Poland crushed Ukrainian independence as the Polish The Home Army was attempting to restore the Polish Republic within its pre-1939 borders.[42] According to Ivan Katchanovski, the mass killings of Poles in Volhynia by UPA cannot be classified as a genocide because there is no evidence that UPA intended to annihilate entire or significant part of the Polish nation, UPA action was mostly limited to a relatively small area and the number of Poles killed constituted a very small fraction of the prewar Polish population on territories where UPA operated and of the entire Polish population in Poland and Ukraine.[147]

The Institute of National Remembrance investigated the crimes committed by UPA against the Poles in Volhynia, Galicia, and prewar Lublin Voivodeship; collecting over 10,000 pages of documents and protocols. The massacres were described by the Commission's prosecutor Piotr Zając as bearing the characteristics of a genocide—according to Zając: "there is no doubt that the crimes committed against the people of Polish nationality have the character of genocide".[179] Also, the Institute of National Remembrance in a published paper stated that:

The Volhynian massacres have all the traits of genocide listed in the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which defines genocide as an act "committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such." [180]

On 15 July 2009 the Sejm of the Republic of Poland unanimously adopted a resolution regarding "the tragic fate of Poles in Eastern Borderlands". The text of the resolution states that July 2009 marks the 66th anniversary "of the beginning of anti-Polish actions by the Organization of Ukrainian nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army on Polish Eastern territories – mass murders characterised by ethnic cleansing with marks of genocide."[181] On 22 July 2016, the Sejm passed a resolution declaring 11 July a National Day of Remembrance to honor the Polish victims murdered in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia by Ukrainian nationalists, and formally calling the massacres a Genocide.[16][17]

In popular culture

The events of the Massacre of Poles in Volhynia are depicted in the 2016 movie "Volhynia".

See also

- Historiography of the Massacre of Poles in Volhynia

- 27th Polish Home Army Infantry Division

- Janowa Dolina massacre

- Operation Vistula

- Poryck Massacre

- Przebraże Defence

- Koliyivschyna

- Massacre of Ostrówki

- Marianna Dolinska

- Kisielin massacre

- Bloody Sunday on Volhynia

- Korosciatyn massacre

- Parośla I massacre

- Huta Pieniacka massacre

- Pidkamin massacre

- Palikrowy massacre

- Baligród massacre

- Massacre of Wola Ostrowiecka

- Muczne massacre

- Wiązownica massacre

- Chrynów massacre

- Gurów massacre

- Dominopol massacre

- Wiśniowiec massacres

- Gaj massacres

- Hurby massacre

- Głęboczyca massacre

- Zagaje massacre

- Budy Ossowskie massacre

Notes

- ^ Massacre, Volhynia. "What were the Volhynian Massacres?". Volhynia Massacre. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ a b c d Timothy Snyder. "A Fascist Hero in Democratic Kiev". The New York Review of Books. NYR Daily.

Bandera aimed to make of Ukraine a one-party fascist dictatorship without national minorities... UPA partisans murdered tens of thousands of Poles, most of them women and children. Some Jews who had taken shelter with Polish families were also killed.

- ^ Filip Mazurczak (13 July 2016). "The Volhynia Genocide and Polish-Ukrainian Reconciliation". Visegrad Insight.

UPA's methods were sadistic.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Siemaszko, Ewa. The July 1943 genocidal operations of OUN-UPA in Volhynia (PDF). pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-01.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) The Polish underground document provides a condensed account of this terrible savagery. - ^ a b c Massacre, Volhynia. "The Effects of the Volhynian Massacres". Volhynia Massacre. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ a b ""Od rzezi wołyńskiej do akcji Wisła. Konflikt polsko-ukraiński 1943-1947"". dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-03-10.

- ^ a b J. P. Himka. Interventions: Challenging the Myths of Twentieth-Century Ukrainian history. University of Alberta. 28 March 2011. p. 4

- ^ Henryk Komański and Szczepan Siekierka, Ludobójstwo dokonane przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich na Polakach w województwie tarnopolskim w latach 1939–1946 (2006) 2 volumes, 1182 pages, at pg. 203

- ^ a b Mark Mazower, Hitler's Empire, pages 506–507. Penguin Books 2008. ISBN 978-0-14-311610-3

- ^ "The Witnesses". Special issue. Institute of National Remembrance.

The participation of the Ukrainian clergy was significant. In many localities Orthodox priests consecrated the murder tools.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Michał Klimecki (2013). "Combat involvement of Poland's 27th Infantry Division of the Volhynia Home Army against UPA" (PDF). Institute of National Remembrance. 5 / 8 in PDF. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-12.

Polish forces engaged the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in a series of offensive combat actions. One of the first such confrontations was on January 10–15, 1944.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Snyder 2003, p. 175.

- ^ Burds, Jeffrey (1999). "Comments on Timothy Snyder's article, "To Resolve the Ukrainian Question once and for All: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ukrainians in Poland, 1943–1947"". 1 (2). Journal of Cold War Studies. (1) Chronology.

The more I study Galicia, the more I come to the conclusion that *the defining issue was not Soviet or German occupation and war, but rather the civil war between ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Poles.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Piotr Zając, "Prześladowania ludności narodowości polskiej na terenie Wołynia w latach 1939–1945 – ocena karnoprawna zdarzeń w oparciu o ustalenia śledztwa OKŚZpNP w Lublinie" [in:] Zbrodnie przeszłości. Opracowania i materiały prokuratorów IPN, t. 2: Ludobójstwo, red. Radosław Ignatiew, Antoni Kura, Warszawa 2008, p.34-49. Quote="W świetle przedstawionych wyżej ustaleń nie ulega wątpliwości, że zbrodnie, których dopuszczono się wobec ludności narodowości polskiej, noszą charakter niepodlegających przedawnieniu zbrodni ludobójstwa."

- ^ PolskieRadio.pl (2 June 2013), Prezes IPN: zbrodnia na Wolyniu to ludobojstwo.

- ^ a b Polish "Senate recognizes Volhynia massacre to be genocide." http://tass.ru/en/world/887135 http://tass.ru/en/world/887135

- ^ a b Radio Poland "Polish MPs adopt resolution calling 1940s massacre genocide" http://www.thenews.pl/1/10/Artykul/263005,Polish-MPs-adopt-resolution-calling-1940s-massacre-genocide

- ^ Walter G. Moss (2003). A History of Russia. Anthem Press. pp. 56, 60, 65. ISBN 0857287524 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Peter J. Potichnyj (1980). Poland and Ukraine, past and present. CIUS Press (University of Alberta). pp. 59, 60. ISBN 978-0-920862-07-0.

- ^ Grzegorz Motyka, Ukraińska partyzantka 1942–1960, Warszawa 2006

- ^ a b Orest Subtelny (1994). Ukraine. A history. University of Toronto Press. pp. 430–431. ISBN 0-8020-0591-8.

- ^ Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: a history, pp. 367–368, University of Toronto Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8020-8390-0

- ^ a b Timothy Snyder. The Reconstructions of Nations. Yale University Press. 2003. p. 176

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003) The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp.138–139

- ^ a b The Unknown Lenin, ed. Richard Pipes, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-06919-7 Document 59, Google Print, p. 106.

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, University of Toronto Press: Toronto 1996, ISBN 0-8020-0830-5

- ^ Kubijovic, V. (1963). Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Snyder 2003, pp. 165, 166, 168.

- ^ John Armstrong (1963). Ukrainian Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 21–22

- ^ Wilson, A. (2000). The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Paul Robert Magocsi. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 621

- ^ The theory and teachings of the Ukrainian nationalists were very close to Fascism, and in some respects such as the insistence on 'racial purity', even went beyond the original fascist doctrines. John A. Armstrong. Ukrainian nationalism (1980). Ukrainian Academic Press. p. 280.

- ^ Bohdan Budurowycz. (1989). Sheptytski and the Ukrainian National Movement after 1914 (chapter). In Paul Robert Magocsi (ed.). Morality and Reality: The Life and Times of Andrei Sheptytsky. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta. pg. 57.

- ^ a b Timothy Snyder. (2003)The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943, The Past and Present Society: Oxford University Press. p. 202

- ^ Timothy Snyder. (2005). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 32–33, 152–162

- ^ a b c Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine, A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 430.

- ^ The police also reported wounding 20 communists in 1935, and in one case wounded at least seven people while being attacked by a large group armed with sickles and clubs. The communists retaliated against those who failed to participate in strikes. From: Timothy Snyder (2007). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. Yale University Press. pp. 137, 142.

- ^ a b c Timothy Snyder. (2005). Sketches from a Secret War: A Polish Artist's Mission to Liberate Soviet Ukraine. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp.167

- ^ Subtelny, Orest. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 432.

- ^ Lidia Głowacka, Andrzej Czesław Żak, Osadnictwo wojskowe na Wolyniu w latach 1921–1939 w swietle dokumentów centralnego archiwum wojskowego Archived 2014-08-15 at the Wayback Machine (Military Settlers in Volhynia in the years 1921–1939), PDF, pp. 143 (4 / 25 in PDF), 153 (14 / 25 in PDF). "Mimo ogromnych trudności, kryzysu gospodarczego na początku lat 30. i złożonej sytuacji politycznej na tym terenie, osadnicy zdołali zagospodarować znaczne obszary ziemi i stworzyć od podstaw wiele osad z nowoczesną –jak na owe czasy –infrastrukturą. W 1939 r. na Wołyniu mieszkało około 17,7 tys. osadników wojskowych i cywilnych w ponad 3,500 osad."

- ^ a b Subtelny, O. (1988). Ukraine: a History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 429. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6

- ^ a b c d e f A. Rudling. Theory and Practice. Historical representation of the wartime accounts of the activities of OUN-UPA (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists-Ukrainian Insurgent Army). East European Jewish Affairs. Vol. 36. No.2. December 2006. pp. 163–179.

- ^ Motyka, Ukraińska partyzantka ..., p. 58

- ^ The assassinations of foreign affairs minister Bronisław Pieracki or of a supporter of peaceful Polish-Ukrainian cooperation, Tadeusz Hołówko, are two examples of OUN-B terrorist campaign.

- ^ In one of many such incidents, the Papal Nuncio in Warsaw reported that Polish mobs attacked Ukrainian students in their dormitory under the eyes of Polish police, a screaming Ukrainian woman was thrown into a burning Ukrainian store by Polish mobs, and a Ukrainian seminary was destroyed during which religious icons were desecrated and eight people were hospitalized with serious injuries and two killed. See Burds 1999.

- ^ a b Burds 1999.

- ^ Template:Uk icon Oleksandr Derhachov (editor), "Ukrainian Statehood in the Twentieth Century: Historical and Political Analysis", 1996, Kiev ISBN 966-543-040-8. section 2, subsection 2

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 144.

- ^ Сивицький, М. Записки сірого волиняка Львів 1996 с.184

- ^ Orest Subtelny. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp.444.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Snyder 2001.

- ^ Oleksandr Zinchenko (2 December 2010). "Година папуги" майора Людвіка Домоня ["The hour of the parrot" Major Ludwig Domont]. istpravda.com.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Poland's Holocaust, Tadeusz Piotrowski, 1998 ISBN 0-7864-0371-3 p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen, Immigration and Asylum, page 204. Books.google.com. Retrieved on 11 July 2011.

- ^ John Armstrong (1963). Ukrainian Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press, pg. 65

- ^ Orest Subtelny. (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 455–457.

- ^ Matthew J. Gibney, Randall Hansen.Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. 2005. p. 205.

- ^ Ivan Katchanovski. The Politics of World War II in Contemporary Ukraine 2013. p. 17.

- ^ Dr. Frank Grelka (2005). Ukrainischen Miliz. Viadrina European University: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 283–284. ISBN 3447052597. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Causes of Ukrainian-Polish Ethnic Cleansing 1943, The Past and Present Society: Oxford University Press. pg. 207

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 163.

- ^ Snyder 2003, p. 162.

- ^ a b Snyder 2003, pp. 164–5.

- ^ Taras Bulba-Borovets wrote: The axe and the flail have gone into motion. Whole families are butchered and hanged, and Polish settlements are set on fire. The 'hatchet men', to their shame, butcher and hang defenseless women and children....By such work Ukrainians not only do a favor for the SD [German security service], but also present themselves in the eyes of the world as barbarians. We must take into account that England will surely win this war, and it will treat these 'hatchet men' and lynchers and incendiaries as agents in the service of Hitlerite cannibalism, not as honest fighters for their freedom, not as state-builders. John Paul Himka. Ukrainian past and future. September 20, 2010, Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Snyder 2003, p. 168.

- ^ "From a Polish point of view, the defeat of both Germany and Russia would open the field in the east. As early as 1941, it was understood that a future rising against German power would involve a war against Ukrainians for Eastern Galicia and probably Volhynia as well, to be prosecuted if possible as a quick "armed occupation."[15] The AK's plans for a rising, as formulated in 1942, anticipated a war with Ukrainians for the ethnographically Ukrainian territories that fell within Poland's prewar boundaries. By 1942 the formation of sizable Polish partisan units in the east could not but remind Ukrainians of Polish territorial claims." (Snyder 2001)