Back to the Future

| Back to the Future | |

|---|---|

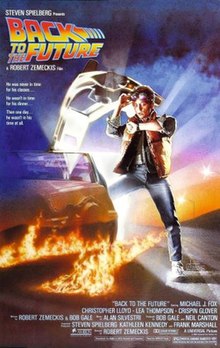

Theatrical release poster by Drew Struzan | |

| Directed by | Robert Zemeckis |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Alan Silvestri |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $19 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $389.1 million[3][4][5] |

Back to the Future is a 1985 American science fiction film directed by Robert Zemeckis and written by Zemeckis and Bob Gale. It stars Michael J. Fox as teenager Marty McFly, who accidentally travels back in time from 1985 to 1955, where he meets his future parents and becomes his mother's romantic interest. Christopher Lloyd portrays the eccentric scientist Doctor Emmett "Doc" Brown, his friend and the inventor of the time-traveling DeLorean automobile, who helps Marty repair history and return to 1985. The cast also includes Lea Thompson as Marty's mother Lorraine, Crispin Glover as his father George, and Thomas F. Wilson as Biff Tannen, Marty and George's arch-nemesis.

Zemeckis and Gale wrote the script after Gale wondered whether he would have befriended his father if they had attended school together. Film studios rejected it until the financial success of Zemeckis' Romancing the Stone. Zemeckis approached Steven Spielberg, who agreed to produce the project at Amblin Entertainment, with Universal Pictures as distributor. Fox was the first choice to play Marty, but he was busy filming his television series Family Ties, and Eric Stoltz was cast; after the filmmakers decided he was wrong for the role, a deal was struck to allow Fox to film Back to the Future without interrupting his television schedule.

Back to the Future was released on July 3, 1985. It grossed over $381 million worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1985. It won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, the Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film, and the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing. It received three Academy Award nominations, five BAFTA nominations, and four Golden Globe nominations, including Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy). In 2007, the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry, and in June 2008 the American Film Institute's special AFI's 10 Top 10 designated it the 10th-best science fiction film. The film began a franchise including two sequels, Back to the Future Part II (1989) and Back to the Future Part III (1990), an animated series, a theme park ride, several video games, a series of comic books, and a stage musical.

Plot

In 1985, Hill Valley, California, Marty McFly visits the home and lab of his friend, Emmett "Doc" Brown, an eccentric scientist. Though missing for several days, Doc calls the lab and asks Marty to pick up some equipment for a special experiment later that night.

At school, Marty meets his girlfriend, Jennifer Parker, and after being berated by the principal and failing his audition for the Battle of the Bands, he confides in Jennifer about fears of becoming like his parents despite his ambitions. At home, Marty's cowardly father George is bullied by his supervisor, Biff Tannen, while his mother Lorraine is a depressed alcoholic. Lorraine recalls how she met George when her father hit him with his car and she subsequently nursed him back to health.

Marty meets Doc at a shopping mall parking lot at 1:16 A.M. on October 26. Doc unveils a time machine built from a modified DeLorean and powered by plutonium obtained from Libyan terrorists with the promise of building them a nuclear bomb. While showing Marty the controls, Doc sets the date to November 5, 1955 – the day he conceived a time travel device. The terrorists arrive unexpectedly and open fire on them, eventually shooting Doc when he surrenders. Marty escapes in the DeLorean and inadvertently activates the time machine in the process.

Marty finds himself transported to November 5, 1955, without any plutonium to return. He encounters the teenage George and discovers that Biff has been bullying him since high school. After Marty saves George from an oncoming car, he is knocked unconscious and awakens to find himself tended to by Lorraine, who becomes infatuated with him.

Marty tracks down Doc's younger self for help. Doc is unimpressed with Marty's knowledge of the future but finally believes him when he accurately recounts how Doc invented time travel. With no plutonium, Doc explains that the only power source capable of generating the required 1.21 GW of electricity for the time machine is a bolt of lightning. Marty shows Doc a fundraising flyer from the future that documents an upcoming lightning strike at the town's courthouse. Doc instructs Marty to avoid leaving his house and interacting with others, as he could inadvertently alter the future, but they realize he may already have. Saving George earlier prevented his parents from meeting. Doc warns that Marty may fail to exist if Lorraine doesn't fall in love with George. Early attempts to introduce his parents fail, and Lorraine's infatuation with Marty only deepens during a confrontation with Biff. Marty also hides a handwritten note telling Doc about his future.

After Lorraine asks Marty to the school dance, Marty devises a plan with George: he will feign inappropriate advances on Lorraine, allowing George to step in and "rescue" her. The plan goes awry when a drunken Biff gets rid of Marty, and his gang locks him in the trunk of the performing band's car. The band frees Marty and drives away Biff's gang. Meanwhile, Biff attempts to force himself onto Lorraine, and an enraged George knocks him out. He wins over Lorraine who accompanies him to the dance floor. They kiss while Marty performs with the band, restoring his future existence.

As the storm arrives, Marty returns to the clock tower. Doc finds the hidden note and tears it up, saying no one should know too much about their own destiny. The lightning strikes, sending Marty back to 1985 moments before his original departure. After watching Doc get shot again, he grieves until Doc sits up and reveals that he wore a bulletproof vest; Doc had taped Marty's note back together. He takes Marty home and departs to the future. Marty awakens the next morning to find that his father is now a successful author full of self-confidence, his mother is fit and happy, and Biff is now an obsequious auto valet. As Marty reunites with Jennifer, Doc suddenly reappears with the DeLorean, insisting that they return with him to aid their future children. The trio boards the DeLorean, which now flies, and travels into the future.

Cast

|

|

|

Huey Lewis plays one of the judges for the 1985 Battle of the Bands contest.[6]

Production

Development

Writer and producer Bob Gale conceived Back to the Future after visiting his parents in St. Louis, Missouri, after the release of Used Cars. Searching their basement, Gale found his father's high school yearbook and discovered he was president of his graduating class. Gale had not known the president of his own graduating class, and wondered whether he would have been friends with his father if they had gone to high school together.[7] When he returned to California, Gale told director Robert Zemeckis about the idea.[8] Zemeckis thought of a mother claiming she never kissed a boy at school when, in fact, she had been promiscuous.[9] The two took the project to Columbia Pictures, and made a development deal for a script in September 1980.[8]

Zemeckis and Gale set the story in 1955 because an 18-year-old traveling to meet his parents at the same age arithmetically required the script to travel to that decade. The era also marked the rise of teenagers as an important cultural element, the birth of rock 'n' roll, and suburban expansion, which flavored the story.[10] In an early script, the time machine was a refrigerator, and Marty would need the power of an atomic explosion at the Nevada Test Site to return home. Zemeckis was concerned that children would accidentally lock themselves in refrigerators and felt it was more useful if the time machine were mobile. The DeLorean was chosen because its design made the gag about the family of farmers mistaking it for a flying saucer believable.[11] Zemeckis and Gale found it difficult to create a believable friendship between Marty and Brown before they created the giant guitar amplifier, and only resolved Marty's Oedipal relationship with his mother when they wrote the line "It's like I'm kissing my brother." Biff Tannen was named after studio executive Ned Tanen, who behaved aggressively toward Zemeckis and Gale during a script meeting for I Wanna Hold Your Hand.[9] Gale also later claimed that Biff's character was based on Donald Trump.[12]

The first draft of Back to the Future was finished in February 1981 and presented to Columbia, who put the film in turnaround. "They thought it was a really nice, cute, warm film, but not sexual enough," Gale said. "They suggested that we take it to Disney, but we decided to see if any other of the major studios wanted a piece of us."[8] Every major film studio rejected the script for the next four years, while it went through two more drafts. During the early 1980s, popular teen comedies (such as Fast Times at Ridgemont High and Porky's) were risqué and adult-aimed, so the script was rejected for being too light.[9] Gale and Zemeckis finally pitched Back to the Future to Disney, but they felt the story of a mother falling in love with her son was not appropriate for a family film under the Disney name.[8]

The two were tempted to ally themselves with Steven Spielberg, who had produced Used Cars and I Wanna Hold Your Hand, which were both box office bombs. They had initially shown the screenplay to Spielberg, who had "loved" it.[13] Spielberg, however, was absent from the project during development because Zemeckis felt if he produced another flop under him, he would never be able to make another film.[13] Gale said "We were afraid that we would get the reputation that we were two guys who could only get a job because we were pals with Steven Spielberg."[14] Zemeckis chose to direct Romancing the Stone instead, which was a box office success. Now a high-profile director, Zemeckis reapproached Spielberg with the concept.[9] Agreeing to produce Back to the Future, Spielberg set the project up at his production company, Amblin Entertainment, with Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall joining Spielberg as executive producers on the film.[15][16]

The script remained with Columbia until legal problems forced them to withdraw. The studio was set to begin shooting a comedic send-up of Double Indemnity entitled Big Trouble. Columbia's legal department determined that the film's plot was too similar to Double Indemnity and they needed the permission of Universal Pictures, owners of the earlier film, if the film was ever to begin shooting. With Big Trouble set to go, desperate Columbia executives phoned Universal's Frank Price to get the necessary paperwork. Price was a former Columbia executive who had been fond of the script for Back to the Future during his tenure there. As a result, Universal agreed to trade the Double Indemnity license in exchange for the rights to Back to the Future.[17]

Executive Sidney Sheinberg suggested changes to the script, such as changing Marty's mother's name from Meg to Lorraine (the name of his wife, actress Lorraine Gary), changing Brown's name from Professor Brown to Doc Brown, and replacing Doc's pet chimpanzee with a dog.[9] Sheinberg also wanted the title changed to Space Man from Pluto,[18] convinced no successful film ever had "future" in the title. He suggested that the scene with Marty dressed as an alien should have Marty identify himself as "a space man from the Planet Pluto" [sic] instead of "Darth Vader from Vulcan",[18] and that the farmer's son's comic book be titled Spaceman from Pluto rather than Space Zombies from Pluto. Appalled, Zemeckis asked Spielberg for help. Spielberg dictated a memo to Sheinberg convincing him they thought his title was a joke, thus embarrassing him into dropping the idea.[19] The original climax in which Marty went back to 1985 by driving through a nuclear explosion during a weapons test in Nevada was deemed too expensive by Universal executives and was simplified by keeping the plot within Hill Valley and incorporating the clocktower sequence. Spielberg used the omitted refrigerator and Nevada nuclear site elements in his 2008 film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.[20]

Casting

Michael J. Fox was the first choice to play Marty McFly, but he was committed to the show Family Ties.[21] Family Ties producer Gary David Goldberg felt that Fox was essential to the show's success. With co-star Meredith Baxter on maternity leave, he refused to allow Fox time off to work on a film. Back to the Future was originally scheduled for a May 1985 release, and it was late 1984 when it was learned that Fox would be unable to star in the film.[9] Zemeckis's next two choices were C. Thomas Howell and Eric Stoltz. Stoltz impressed the producers enough with his earlier portrayal of Roy L. Dennis in Mask (which had yet to be released) that they selected him to play Marty McFly.[7] Because of the difficult casting process, the start date was pushed back twice.[22] John Cusack was also considered for the role.[23] Johnny Depp also auditioned for the role of Marty McFly.[23]

Principal photography began in November 1984, but a few weeks into filming, Zemeckis determined Stoltz had been miscast. Although he and Spielberg realized that re-shooting the film would add $3 million to the $14 million budget, they decided to recast. Zemeckis believed Stoltz was not comedic enough and that he gave a "terrifically dramatic performance". Gale further explained they felt Stoltz was simply acting out the role, whereas Fox himself had a personality like Marty McFly. He felt Stoltz was uncomfortable riding a skateboard, whereas Fox was not. Stoltz confessed to director Peter Bogdanovich during a phone call, two weeks into the shoot, that he was unsure of Zemeckis's and Gale's direction, and concurred that he was wrong for the role.[9]

Fox's schedule was opened up in January 1985 when Baxter returned to Family Ties following her pregnancy. The Back to the Future crew met with Goldberg again, who made a deal that Fox's main priority would be Family Ties, and if a scheduling conflict arose, "we win". Fox loved the script and was impressed by Zemeckis's and Gale's sensitivity in releasing Stoltz because they nevertheless "spoke very highly of him".[9] Per Welinder and Bob Schmelzer assisted on the skateboarding scenes.[24] Fox found his portrayal of Marty McFly to be very personal. "All I did in high school was skateboard, chase girls and play in bands. I even dreamed of becoming a rock star."[21]

Jeff Goldblum originally auditioned for the role of Doc Brown, but lost it to Christopher Lloyd.[23] Christopher Lloyd was cast as Doc Brown after the first choice, John Lithgow, became unavailable.[9] Having worked with Lloyd on The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai (1984), producer Neil Canton suggested him for the part. Lloyd originally turned down the role, but changed his mind after reading the script and at the insistence of his wife. He improvised some of his scenes,[25] taking inspiration from Albert Einstein and conductor Leopold Stokowski.[26][27] Lloyd pronounced gigawatts as "jigawatts," which was the way a physicist would say the word, when he met with Zemeckis and Gale as they researched the script[24][28] (rather than with an initial hard "g", although both pronunciations are acceptable).[29][30] Doc Brown's hunched posture came about because at 6 feet 1 inch (1.85 m) Lloyd was considerably taller than Fox at 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m), and they needed to look closer in height.[31]

Crispin Glover played George McFly. Zemeckis said Glover improvised many of George's nerdy mannerisms, such as his shaky hands. The director joked he was "endlessly throwing a net over Crispin because he was completely off about fifty percent of the time in his interpretation of the character."[9] Due to a contract disagreement, Glover was replaced by Jeffrey Weissman in Part II and Part III.[32]

Lea Thompson was cast as Lorraine McFly because she had acted opposite Stoltz in The Wild Life; the producers noticed her as they had watched the film while casting Stoltz.[33] Her prosthetic makeup for scenes at the beginning of the film, set in 1985, took three and a half hours to apply.[34]

Thomas F. Wilson was cast as Biff Tannen because the producers felt that the original choice, J. J. Cohen, wasn't physically imposing enough to bully Stoltz.[9] Cohen was recast as Skinhead, one of Biff's cohorts. Had Fox been cast from the beginning, Cohen probably would have won the part because he was sufficiently taller than Fox.[24]

Melora Hardin was originally cast in the role of Marty's girlfriend, Jennifer, but was let go after Stoltz was dismissed, with the explanation that the actress was now too tall to be playing against Fox.[23] Hardin was dismissed before she had a chance to shoot a single scene and was replaced with Claudia Wells.[35] Actress Jill Schoelen had also been considered to play Marty's girlfriend.[36]

Filming

Following Stoltz's departure, Fox's schedule during weekdays consisted of filming Family Ties during the day, and Back to the Future from 6:30 pm to 2:30 am. He averaged five hours of sleep each night. During Fridays, he shot from 10 pm to 6 or 7 am, and then moved on to film exterior scenes throughout the weekend, as only then was he available during daytime hours. Fox found it exhausting, but "it was my dream to be in the film and television business, although I didn't know I'd be in them simultaneously. It was just this weird ride and I got on."[38] Zemeckis concurred, dubbing Back to the Future "the film that would not wrap". He recalled that because they shot night after night, he was always "half asleep" and the "fattest, most out-of-shape and sick I ever was".[9]

The Hill Valley town square scenes were shot at Courthouse Square, located in the Universal Studios backlot. Gale explained it would have been impossible to shoot on location "because no city is going to let a film crew remodel their town to look like it's in the 1950s." The filmmakers "decided to shoot all the 50s stuff first, and make the town look real beautiful and wonderful. Then we would just totally trash it down and make it all bleak and ugly for the 1980s scenes."[38] The interiors for Doc Brown's house were shot at the Robert R. Blacker House, while exteriors took place at Gamble House.[39] The exterior shots of the Twin Pines Mall, and later the Lone Pine Mall (from 1985) were shot at the Puente Hills Mall in City of Industry, California. The exterior shots and some interior scenes at Hill Valley High School were filmed at Whittier High School in Whittier, California. The Battle of the Bands tryout scene was filmed at the McCambridge Park Recreation Center in Burbank, and the "Enchantment Under the Sea" dance was filmed in the gymnasium at Hollywood United Methodist Church. The scenes outside of the Baines' house in 1955 were shot at Bushnell Avenue, South Pasadena, California.[40]

Filming wrapped after 100 days on April 20, 1985, and the film was delayed from May to August. But after a highly positive test screening ("I'd never seen a preview like that," said Frank Marshall, "the audience went up to the ceiling"), Sheinberg chose to move the release date to July 3. To make sure the film met this new date, two editors, Arthur Schmidt and Harry Keramidas, were assigned to the picture, while many sound editors worked 24-hour shifts. Eight minutes were cut, including Marty watching his mom cheat during an exam, George getting stuck in a telephone booth before rescuing Lorraine, as well as much of Marty pretending to be Darth Vader. Zemeckis almost cut out the "Johnny B. Goode" sequence as he felt it did not advance the story, but the preview audience loved it, so it was kept. Industrial Light & Magic created the film's 32 effects shots, which did not satisfy Zemeckis and Gale until a week before the film's completion date.[9] The compositing involved for the film's time travel sequences, as well as for the lightning effects in the climactic clock tower scene, were handled by animation supervisor Wes Takahashi, who would also work on the subsequent two Back to the Future films with the rest of the ILM crew.[41]

Music

Alan Silvestri collaborated with Zemeckis on Romancing the Stone, but Spielberg disliked that film's score. Zemeckis advised Silvestri to make his compositions grand and epic, despite the film's small scale, to impress Spielberg. Silvestri began recording the score two weeks before the first preview. He also suggested that Huey Lewis and the News create the theme song. Their first attempt was rejected by Universal, before they recorded "The Power of Love".[38] The studio loved the final song but were disappointed it did not feature the film's title, so they had to send memos to radio stations to always mention its association with Back to the Future.[9] In the end, the track "Back in Time" was featured in the film, playing during the scene when Marty wakes up after his return to 1985, and during the end credits.[38]

Although it appears that Fox is actually playing a guitar, music supervisor Bones Howe hired Hollywood guitar coach and musician Paul Hanson to teach Fox to simulate playing all the parts so it would look realistic, including playing behind his head. Fox lip-synched "Johnny B. Goode" to vocals by Mark Campbell (of Jack Mack and the Heart Attack fame).[42]

The original 1985 soundtrack album only included two tracks culled from Silvestri's compositions for the film, both Huey Lewis tracks, the songs played in the film by the fictional band Marvin Berry and The Starlighters (and Marty McFly), one of the vintage 1950s songs in the movie, and two pop songs that are only very briefly heard in the background of the film.[citation needed] On November 24, 2009, an authorized, limited-edition two-CD set of the entire score was released by Intrada Records.[43]

Release

Back to the Future opened on July 3, 1985, on 1,200 screens in North America. Zemeckis was concerned the film would flop because Fox had to film a Family Ties special in London and was unable to promote the film. Gale was also dissatisfied with Universal Pictures' tagline "Are you telling me my mother's got the hots for me?".

When the film was released on VHS in 1986, Universal added a "To be continued..." graphic at the end to increase awareness of production on Part II. This caption is omitted on the film's DVD release in 2002[27] and on subsequent Blu-ray and DVD releases.

In October 2010, in commemoration for the film's 25th anniversary, Back to the Future was digitally restored and remastered for a theatrical re-release in the US, the UK and Italy.[44] The release also coincided with Universal Pictures Blu-ray Disc release of the trilogy, which was released on October 26.[45][46]

On October 21, 2015,[47] the futuristic date depicted in Part II, the entire trilogy was re-released theatrically for one day in celebration of the film's 30th anniversary.[48]

Reception

Box office

Back to the Future spent 11 weeks at number one.[9] Gale recalled "Our second weekend was higher than our first weekend, which is indicative of great word of mouth. National Lampoon's European Vacation came out in August and it kicked us out of number one for one week and then we were back to number one."[14] The film went on to gross $210.61 million in North America and $178.5 million in foreign countries, accumulating a worldwide total of $389.1 million.[4] Back to the Future had the fourth-highest opening weekend of 1985 and was the top-grossing film of the year.[49] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 59 million tickets in the United States.[50]

Critical response

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 96% of critics gave the film a positive review based on 80 reviews; the average rating is 8.73/10. The website's consensus reads: "Inventive, funny, and breathlessly constructed, Back to the Future is a rousing time-travel adventure with an unforgettable spirit."[51] On review aggregator Metacritic the film received an average score of 87, based on 26 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[52]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times felt Back to the Future had similar themes to the films of Frank Capra, especially It's a Wonderful Life. Ebert commented "[Producer] Steven Spielberg is emulating the great authentic past of Classical Hollywood cinema, who specialized in matching the right director (Robert Zemeckis) with the right project." He gave the film 3½ out of 4 stars.[53] Janet Maslin of The New York Times believed the film had a balanced storyline: "It's a cinematic inventing of humor and whimsical tall tales for a long time to come."[54] Christopher Null, who first saw the film as a teenager, called it "a quintessential 1980s flick that combines science fiction, action, comedy, and romance all into a perfect little package that kids and adults will both devour."[55] Dave Kehr of Chicago Reader felt Gale and Zemeckis had written a script that perfectly balanced science fiction, seriousness and humor.[56] Variety praised the performances, arguing Fox and Lloyd imbued Marty and Doc Brown's friendship with a quality reminiscent of King Arthur and Merlin.[57] BBC News lauded the intricacies of the "outstandingly executed" script, remarking that "nobody says anything that doesn't become important to the plot later."[58] Dennis Fischer of Cinefantastique gave the film four stars out of five, calling it an "instant classic".[59] Back to the Future appeared on Gene Siskel's top ten film list of 1985.[60]

Accolades

At the 58th Academy Awards, Back to the Future won for Best Sound Effects Editing, while Zemeckis and Gale were nominated for Best Original Screenplay, "The Power of Love" was nominated for Best Original Song, and Bill Varney, B. Tennyson Sebastian II, Robert Thirlwell and William B. Kaplan were nominated for Best Sound Mixing.[61] The film won the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation[62] and the Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film. Michael J. Fox and the visual effects designers won categories at the Saturn Awards. Zemeckis, composer Alan Silvestri, the costume design and supporting actors Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, Crispin Glover and Thomas F. Wilson were also nominated.[63] The film was nominated for numerous BAFTAs at the 39th British Academy Film Awards, including Best Film, original screenplay, visual effects, production design and editing.[64] At the 43rd Golden Globe Awards, Back to the Future was nominated for Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy), original song (for "The Power of Love"), Best Actor in a Motion Picture Musical or Comedy (Fox) and Best Screenplay for Zemeckis and Gale.[65]

Legacy

President Ronald Reagan, a fan of the film, referred to the film in his 1986 State of the Union Address when he said, "Never has there been a more exciting time to be alive, a time of rousing wonder and heroic achievement. As they said in the film Back to the Future, 'Where we're going, we don't need roads'."[66] When he first saw the joke about him being president, he ordered the projectionist of the theater to stop the reel, roll it back, and run it again.[7]

The film ranked number 28 on Entertainment Weekly's list of the 50 Best High School Movies.[67] In 2008, readers of Empire voted Back to the Future the 23rd greatest film of all time.[68] It was also placed on a similar list by The New York Times, a list of 1000 movies.[69] In January 2010, Total Film included the film on its list of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[70] In 2007, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[71] In 2006, the original screenplay for Back to the Future was selected by the Writers Guild of America as the 56th best screenplay of all time.[72]

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed the AFI's 10 Top 10 – the best ten films in ten classic American film genres – after polling more than 1,500 people from the creative community. Back to the Future was acknowledged as the 10th best film in the science fiction genre.[73]

A musical theater production, also called Back to the Future, was announced in 2014 for a production in London's West End theatre. Zemeckis and Gale reunited to write the play, while Silvestri and Glen Ballard provide music.[74] Originally intended to debut in time for the film's 30th anniversary in 2015, the production was delayed on more than one occasion[75] before finally having its premiere set for Feb. 20, 2020.[76]

The scenes of Marty McFly skateboarding in the film took place during the infancy of the skateboarding sub-culture, and numerous skateboarders—as well as companies in the industry—pay tribute to the film for its influence in this regard. Examples can be seen in promotional material, in interviews in which professional skateboarders cite the film as an initiation into the action sport, and in the public's recognition of the film's influence.[77][78]

Back to the Future is ranked tenth on Film4's 50 Films to See Before You Die.[79]

Sequels

Back to the Future's success led to two film sequels: Back to the Future Part II and Back to the Future Part III. Part II was released on November 22, 1989, to initially mixed reviews and similar financial success as the original, finishing as the third highest-grossing film of the year worldwide. In later years, however, the film has earned critical praise especially for the performances, direction, cinematography, musical score and the future predictions, with some critics noting it as one of Zemeckis best movies.[80][81] The film continues directly from the ending of Back to the Future and follows Marty and Doc as they travel into the future of 2015, an alternative 1985, and 1955 where Marty must repair the future while avoiding his past self from the original film. Part II became notable for its 2015 setting and predictions of technology such as hoverboards.[82][83][84]

Part III, released on May 25, 1990, concluded the story, following Marty as he travels back to 1885 to rescue a time-stranded Doc. Commercially, Part III was the least successful in the trilogy but has better reviews than Part II.[85]

In popular culture

- The 2011 novel Ready Player One by Ernest Cline, along with its 2018 film adaptation, features the protagonist driving around in a DeLorean time machine from the film.[86][87]

- The central eponymous characters of the animated television series Rick and Morty are inspired by Doc Brown and Marty McFly, respectively.[88]

- The third season of the series Stranger Things pays homage to Back to the Future throughout, including multiple scenes where some of the characters go to a showing of the film.[89]

- The 2020 music video of the song Ringo Starr by Italian indie pop band Pinguini Tattici Nucleari is a resembling reenactment of the Enchantment Under The Sea prom ball scene where Marty plays Johnny B. Goode.[90]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Back to the Future". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ "BACK TO THE FUTURE (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. July 8, 1985. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Back to the Future (1985)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Back to the Future – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ^ * "Back to the Future (2010 re-release) (2010)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Back To The Future (2014 re-issue)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ della Cava, Marco (October 20, 2015). "Huey Lewis almost passed on going 'Back to the Future'". USA Today. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c Back to the Future, The Complete Trilogy – "The Making of the Trilogy, Part 1" (DVD). Universal Home Video. 2002.

- ^ a b c d Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 1–10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Ian Freer (January 2003). "The making of Back to the Future". Empire. pp. 183–187.

- ^ Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 61–70

- ^ "Back To The Future: Ten Things To Know About The Movie". Movie Fanfare. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Skinner, Tom (October 23, 2019). "'Back To The Future' writer reveals Biff Tannen was inspired by Donald Trump". NME. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ a b Gilbey, Ryan (August 25, 2014). "How we made Back to the Future". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ a b Scott Holleran (November 18, 2003). "Brain Storm: An Interview with Bob Gale". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ Koknow, David (June 9, 2015). "How Back to the Future Almost Didn't Get Made". Esquire. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Ellison, Sarah (February 2016). "Meet the Most Powerful Woman in Hollywood". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Blast From The Past On Back To The Future: How Frank Price Rescued Robert Zemeckis' Classic From Obscurity". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Harrison, Ellie (August 30, 2016). "Back to the Future almost had a really bad title: Here's a memo to prove it..." Radio Times. London. Archived from the original on September 2, 2016. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ McBride (1997), pp. 384–385

- ^ Peter Sciretta (July 15, 2009). "How Back To The Future Almost Nuked The Fridge". Slashfilm. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ a b Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 11–20

- ^ Kagan (2003), pp. 63–92

- ^ a b c d "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c Robert Zemeckis, Bob Gale. (2005). Back to the Future: The Complete Trilogy DVD commentary for part 1 [DVD]. Universal Pictures.

- ^ Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 31–40

- ^ Matt Gouras (June 12, 2009). "Lloyd: 'Back to the Future' still gratifying". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale Q&A, Back to the Future [2002 DVD], recorded at the University of Southern California

- ^ "Back to The Future Script" (PDF). imsdb.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ "Gigawatt". Merriam Webster. Archived from the original on July 24, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Gigawatt". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ^ "20 Things You (Probably) Didn't Know About Back To The Future". ShortList. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Banks, Alec (October 22, 2015). "Why Crispin Glover Refused To Do the 'Back to the Future' Sequels". HIGHSNOBIETY. TITEL MEDIA GMBH. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- ^ Harris, Will (February 21, 2012). "Random Roles: Lea Thompson". avclub.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 21–30

- ^ Mattise, Nathan (December 8, 2011). "Marty McFly's Original Girlfriend Goes Back to the Future". Wired. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ "Jill's Spielberg Memories". Fangoria. June 2011. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Rudolph, Christopher (November 12, 2013). "The Surprising History Of The 'Back To The Future' Clock Tower". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Michael J. Fox, Robert Zemeckis, Bob Gale, Steven Spielberg, Alan Silvestri, The Making of Back to the Future (television special), 1985, NBC

- ^ Klastornin, Hibbin (1990), pp. 41–50

- ^ Back to the Future Trilogy DVD, Production Notes

- ^ Failes, Ian (October 21, 2015). "The future is today: how ILM made time travel possible". FXGuide. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ "Music From The Motion Picture Soundtrack Back To The Future". discogs.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- ^ "FSM BBoard: New Intradata: Back to the Future". Film Score Message Board. September 23, 2009. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ "'Back to the Future' 25 years later". The Independent. London. September 29, 2010. Archived from the original on October 2, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Cericola, Rachel (June 29, 2010). "Back to the Future: 25th Anniversary Trilogy Coming to Blu-ray". Big Picture Big Sound. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "'Back to the Future' To Receive 25th Anniversary Theatrical Re-Release". Icon vs. Icon. September 28, 2010. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "These Chicago theaters are showing 'Back to the Future' trilogy on Wednesday". chicago.suntimes.com. October 19, 2015. Archived from the original on October 21, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Martin Liebman. "Back to the Future Trilogy Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ "1985 Domestic Totals". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ "Back to the Future (1985)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ "Back to the Future". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ "Back to the Future Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 3, 1985). "Back to the Future". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (July 3, 1985). "Back to the Future". The New York Times.

- ^ Null, Christopher. "Back to the Future". FilmCritic.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "Back to the Future". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on March 4, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ "Back to the Future". Variety. Reed Elsevier Inc. December 31, 1984. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Unknown (August 2007). "Back to the Future (1985)". BBC. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Fischer, Dennis K. (October 1985). "Film Ratings". Cinefantastique. Vol. 15, no. 4. p. 44.

- ^ The Inner Mind (May 3, 2012). "These ten best lists for movie critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert have been collected from various postings in the Usenet newsgroup rec.arts.movies". The Inner Mind. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ "The 58th Academy Awards (1986) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ "1986 Hugo Awards". The Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "Back to the Future". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ "Back to the Future". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- ^ "President Ronald Reagan's Address Before a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union". C-SPAN. February 4, 1986. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ Cruz, Gilbert. "The 50 Best High School Movies". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Total Film features: 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Total Film. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ^ "National Film Registry 2007, Films Selected for the 2007 National Film Registry". loc.gov. Archived from the original on January 31, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- ^ "101 Best Screenplays as Chosen by the Writers Guild of America, West". wga.org. Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved August 24, 2006.

- ^ "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. June 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Back to the Future musical announced". bbc.co.uk/news. BBC News. January 31, 2014. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- ^ "Back To The Future musical delayed to 2016". Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ "Back to the Future: The Musical finally sets 2020 world premiere". Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Michael Sieben; Stacey Lowery (June 23, 2012). "Welcome Back to the Future Of Radical". Roger Skateboards. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Henry Hanks (October 26, 2010). "Going 'Back to the Future,' 25 years later". CNN Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ "Film4's 50 Films To See Before You Die". Film4. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ "Back to the Future Part II (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Back to the Future Part II". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Ever Movie Sequels: Back To The Future Part II". Empire. 2009. Archived from the original on March 24, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Bricken, Rob (July 3, 2013). "20 Lies Back to the Future II Told Us (Besides the Hoverboard)". io9. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014.

- ^ "We rode a $10,000 hoverboard, and you can too". Engadget. 2014. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Back to the Future Part III (1990)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Gilsdorf, Ethan (June 5, 2012). "Ready Player One Author to Give Away DeLorean". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Power, Ed (March 29, 2018). "Ready Player One: a guide to the legal nightmare of Spielberg's pop culture references". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ Sims, David (December 2, 2013). "Dan Harmon's new series is a warped take on the Doc Brown/Marty McFly dynamic". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Chaney, Jen (July 19, 2019). "Stranger Things 3 Is Basically One Big Back to the Future Homage". Vulture. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ "Pinguini Tattici Nucleari - Ringo Starr (Official Video - Sanremo 2020)". YouTube. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

Bibliography

- Kagan, Norman (2003). "Back to the Future I (1985), II (1989), III (1990)". The Cinema of Robert Zemeckis. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-87833-293-6.

- Klastornin, Michael; Hibbin, Sally (1990). Back to the Future: The Official Book to the Complete Movie Trilogy. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-57104-1.

- Gale, Bob; Robert Zemeckis (1990). "Foreword". Back to the Future: The Official Book to the Complete Movie Trilogy. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-57104-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

- Gale, Bob; Robert Zemeckis (1990). "Foreword". Back to the Future: The Official Book to the Complete Movie Trilogy. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-57104-1.

- Joseph McBride (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

Further reading

- George Gipe (1985). Back to the Future: A Novel. ISBN 978-0-425-08205-8.

- Shail, Andrew; Stoate, Robin (2010). Back to the Future. BFI Film Classic. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-84457-293-9.

- Ni Fhlainn, Sorcha (2010). The Worlds of Back to the Future: Critical Essays on the Films. McFarland Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7864-4400-7.

- Ni Fhlainn, Sorcha (2015). "'There's Something Very Familiar About This': Time Machines, Cultural Tangents and Mastering Time in H.G. Wells' The Time Machine and the Back to the Future Trilogy". Adaptation. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/adaptation/apv028.

- Rich Handley (November 2012). A Matter of Time: The Unauthorized Back to the Future Lexicon. Hasslein Books. ISBN 978-0-578-11344-9.

- Greg Mitchell; Rich Handley (September 2013). Back in Time: The Unauthorized Back to the Future Chronology. Hasslein Books. ISBN 978-0-578-13085-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- Official website

- Back to the Future at IMDb

- Back to the Future at the TCM Movie Database

- Back to the Future at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Back to the Future at Box Office Mojo

- Back to the Future at Rotten Tomatoes

- Back to the Future at Metacritic

- 1985 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 1980s science fiction comedy films

- American science fiction comedy films

- American science fiction adventure films

- American high school films

- American teen comedy films

- Back to the Future films

- Films set in 1955

- Films set in 1985

- Films set in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation winning works

- Films about time travel

- United States National Film Registry films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films adapted into video games

- Films directed by Robert Zemeckis

- Films scored by Alan Silvestri

- Films with screenplays by Bob Gale

- Films with screenplays by Robert Zemeckis

- 1985 comedy films