Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17th President of the United States | |

| In office April 15, 1865 – March 4, 1869 | |

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Succeeded by | Ulysses S. Grant |

| 16th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1865 – April 15, 1865 | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Succeeded by | Schuyler Colfax |

| Military Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office March 12, 1862 – March 4, 1865 | |

| Appointed by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Isham G. Harris |

| Succeeded by | E. H. East (Acting) |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

| In office October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862 March 4, 1875 – July 31, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | James C. Jones William G. Brownlow |

| Succeeded by | David T. Patterson David M. Key |

| 17th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 17, 1853 – November 3, 1857 | |

| Preceded by | William B. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Isham G. Harris |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1843 – March 3, 1853 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas D. Arnold |

| Succeeded by | Brookins Campbell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 29, 1808 Raleigh, North Carolina |

| Died | July 31, 1875 (aged 66) Elizabethton, Tennessee |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic National Union Independent |

| Spouse | Eliza McCardle Johnson |

| Children | Martha Johnson Charles Johnson Mary Johnson Robert Johnson Andrew Johnson, Jr. |

| Occupation | Tailor |

| Signature | |

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808 – July 31, 1875) was the 17th President of the United States (1865–1869). Following the assassination of President Lincoln, Johnson presided over the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War.

At the time of the secession of the Southern states, Johnson was a U.S. Senator from Greeneville in East Tennessee. As a Unionist, he was the only southern senator not to quit his post upon secession. He became the most prominent War Democrat from the South and supported the military policies of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. In 1862, Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor of occupied Tennessee, where he proved to be energetic and effective in fighting the rebellion and beginning transition to Reconstruction.[3]

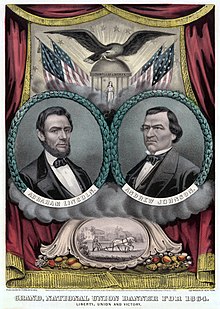

Johnson was nominated for the Vice President position in 1864 on the National Union Party ticket. He and Lincoln were elected in November 1864. Johnson succeeded to the presidency upon Lincoln's assassination on April 15, 1865.

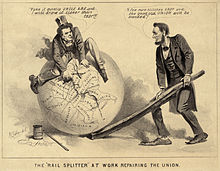

As president, he took charge of Presidential Reconstruction– the first phase of Reconstruction – which lasted until the Radical Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1866 elections. His conciliatory policies towards the South, his hurry to reincorporate the former Confederate states back into the union, and his vetoes of civil rights bills embroiled him in a bitter dispute with some Republicans.[4] The Radicals in the House of Representatives impeached him in 1868, charging him with violating the Tenure of Office Act, a law enacted by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto, but he was acquitted by a single vote in the Senate.

While Johnson is the most recent president to represent a party other than the Republican or Democratic parties, having represented both the Democrats and the National Union Party, his party status was ambiguous during his presidency. As president, he did not identify with the two main parties—though he did try for the Democratic nomination in 1868—and so while President he attempted to build a party of loyalists under the National Union label. Asked in 1868 why he did not become a Democrat, he said, "It is true I am asked why don't I join the Democratic Party. Why don't they join me ... if I have administered the office of president so well?" His failure to make the National Union brand an actual party made Johnson effectively an independent during his presidency, though he was supported by Democrats and later rejoined the party as a Democratic Senator from Tennessee from 1875 till his death. For these reasons he is usually counted as a Democrat when identifying presidents by their political parties.[5]

Johnson was the first U.S. president to succeed to the presidency upon the assassination of his predecessor as well as the first U.S. President to be impeached. He is commonly ranked by historians as being among the worst U.S. presidents.

Early life

Johnson was born on December 29, 1808, in Raleigh, North Carolina, to Jacob Johnson (1778–1812) and Mary McDonough (1783–1856). Jacob died when Andrew was around three years old, leaving his family in poverty. Johnson's mother then took in work spinning and weaving to support her family, and she later remarried. She bound Andrew as an apprentice tailor when he was 10 or 14 years old.[6] In the 1820s, he worked as a tailor in Laurens, South Carolina.[7] Johnson had no formal education and taught himself how to read and write.[3]

At age 16 or 17, Johnson left his apprenticeship and ran away with his brother to Greeneville, Tennessee, where he found work as a tailor.[3][8] At the age of 18, Johnson married Eliza McCardle in 1827. Between 1828 and 1852, the couple had five children: Martha (1828), Charles (1830), Mary (1832), Robert (1834), and Andrew Jr. (1852).[9] Eliza taught Johnson arithmetic up to basic algebra and tutored him to improve his literacy and writing skills.[3]

Early political career

Johnson participated in debates at the local academy at Greeneville, Tennessee[10] and later organized a worker's party that elected him as alderman in 1829. He served in this position until he was elected mayor in 1833.[3] In 1835, he was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives where, after serving a single term, he was defeated for re-election.[9]

Johnson was attracted to the states' rights Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson. He became a spokesman for the more numerous yeomen farmers and mountaineers against the wealthier, but fewer, planter elite families that had held political control both in the state and nationally.[3][10] In 1839, Johnson was elected to a second, non-consecutive term in the Tennessee House, and was elected to the Tennessee Senate in 1841, where he served one two-year term.[9][11] In 1843, he became the first Democrat to win election as the U.S. representative from Tennessee's 1st congressional district. Among his activities for the common man's interests as a member of the House of Representatives and the Senate, Johnson advocated 'a free farm for the poor' bill, in which farms would be given to landless farmers.[10] Johnson was a U.S. representative for five terms until 1853, when he was elected governor of Tennessee.[9]

Political ascendancy

Johnson was elected governor of Tennessee, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was then elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate, serving from October 8, 1857 – March 4, 1862. He was chairman of the Committee to Audit and Control the Contingent Expense (Thirty-sixth Congress). As a U.S. senator, he continued to push for the Homestead Act. It finally passed in 1862, after the Civil War had begun and Southerners had resigned from Congress.

As the slavery question became more critical, Johnson continued to take a middle course. He opposed the antislavery Republican Party because he believed the Constitution guaranteed the right to own slaves. He supported President Buchanan's administration. He also approved the Lecompton Constitution proposed by proslavery settlers in Kansas. At the same time, he made it clear that his devotion to the Union exceeded his devotion to right to own slaves.

Johnson's stand in favor of both the Union and the right to own slaves might have made him a logical compromise candidate for president. However, he was not nominated in 1856 because of a split within the Tennessee delegation. In 1860, the Tennessee delegation nominated Johnson for president at the Democratic National Convention, but when the convention and the party broke up, he withdrew from the race. In the election, Johnson supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, the candidate of most Southern Democrats.[12]

Before Tennessee voted on secession, Johnson, who lived in Unionist East Tennessee, toured the state speaking in opposition to the act, which he said was unconstitutional. Johnson was an aggressive stump speaker and often responded to hecklers, even those in the Senate. At the time of the secession of Tennessee, Johnson was the only Senator from the seceded states to continue participation in Congress. His explanation for this decision was "Damn the negroes, I am fighting those traitorous aristocrats, their masters."[3]

Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor of occupied Tennessee in March 1862 with the rank of brigadier general.[3] During his three years in this office, he "moved resolutely to eradicate all pro-Confederate influences in the state." This "unwavering commitment to the Union" was a significant factor in his choice as vice president by Lincoln.[13] Johnson vigorously suppressed the Confederates and later spoke out for black suffrage, arguing, "The better class of them will go to work and sustain themselves, and that class ought to be allowed to vote, on the ground that a loyal negro is more worthy than a disloyal white man."[14] According to tradition and local lore, on August 8, 1863, Johnson freed his personal slaves.[15]

Vice presidency

As a leading War Democrat and pro-Union southerner, Johnson was an ideal candidate for the Republicans in 1864 as they enlarged their base to include War Democrats. They changed the party name to the National Union Party to reflect this expansion. During the election, Johnson replaced Hannibal Hamlin as Lincoln's running mate. He was elected vice president of the United States and was inaugurated March 4, 1865. At the ceremony, Johnson, who had been drinking to offset the pain of typhoid fever (as he explained later), gave a rambling speech and appeared intoxicated to many. In early 1865, Johnson talked harshly of hanging traitors like Jefferson Davis, which endeared him to radicals.[16]

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln was shot and mortally wounded by John Wilkes Booth, a Confederate sympathizer, while the president was attending a play at Ford's Theater. Booth's plan was to destroy the administration by ordering conspirators to assassinate Johnson, lieutenant general of the Union army Ulysses S. Grant, and Secretary of State William H. Seward that night. Grant survived when he failed to attend the theater with Lincoln as planned, Seward narrowly survived his wounds, while Johnson escaped attack as his would-be assassin, George Atzerodt, failed to go through with the plan.

Presidency 1865–1869

On April 15, 1865, the morning after Lincoln's assassination, Johnson was sworn in as President of the United States by the newly appointed Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Johnson was the first vice president to succeed to the presidency upon the assassination of a president and the third vice president to become a president upon the death of a sitting president.[10][17]

A little known fact about the start of Johnson's presidency is that he was actually drunk when he took the (vice-)presidential oath of office.

Reconstruction

Northern anger over the assassination of Lincoln and the immense human cost of the war led to demands for harsh policies. Vice President Andrew Johnson had taken a hard line and spoke of hanging rebel Confederates. In late April, 1865, he was noted telling an Indiana delegation that, "Treason must be made odious ... traitors must be punished and impoverished ... their social power must be destroyed." However, when he succeeded Lincoln as president, Johnson took a much softer line, commenting, "I say, as to the leaders, punishment. I also say leniency, reconciliation and amnesty to the thousands whom they have misled and deceived,"[18] and ended up pardoning many Confederate leaders.[19]

His class-based resentment of the rich appeared in a May 1865 statement to W.H. Holden, the man he appointed governor of North Carolina: "I intend to confiscate the lands of these rich men whom I have excluded from pardon by my proclamation, and divide the proceeds thereof among the families of the wool hat boys, the Confederate soldiers, whom these men forced into battle to protect their property in slaves."[20] In practice, Johnson was seemingly not harsh toward the Confederate leaders. He allowed the Southern states to hold elections in 1865. Subsequently, prominent former Confederate leaders were elected to the U.S. Congress, which however refused to seat them. Congress and Johnson argued in an increasingly public way about Reconstruction and the manner in which the Southern secessionist states would be readmitted to the Union. Johnson favored a very quick restoration, similar to the plan of leniency that Lincoln advocated before his death.

Break with the Republicans: 1866

Johnson-appointed governments all passed Black Codes that gave the freedmen second class status. In response to the Black Codes and worrisome signs of Southern recalcitrance, the Republicans blocked the readmission of the secessionist states to the Congress in fall 1865. Congress also renewed the Freedman's Bureau, but Johnson vetoed it. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, leader of the moderate Republicans, took affront at the Black Codes. Trumbull proposed the first Civil Rights bill.

Although strongly urged by moderates in Congress to sign the Civil Rights bill, Johnson broke decisively with them by vetoing it on March 27. His veto message objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when eleven out of thirty-six states were unrepresented and attempted to fix, by federal law, "a perfect equality of the white and black races in every State of the Union." Johnson said it was an invasion by federal authority of the rights of the states; it had no warrant in the Constitution and was contrary to all precedents. It was a "stride toward centralization and the concentration of all legislative power in the national government."[21] Johnson, in a letter to Gov. Thomas C. Fletcher of Missouri, wrote, "This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government for white men."[22]

The Democratic Party, proclaiming itself the party of white men, North and South, aligned with Johnson.[23] However, the Republicans in Congress overrode his veto (the Senate by the vote of 33:15, the House by 182:41) and the Civil Rights measure became law.

The last moderate proposal was the Fourteenth Amendment, also written by Trumbull. It was designed to put the key provisions of the Civil Rights Act into the Constitution, but it went further. It extended citizenship to every person born in the United States (except Indians on reservations), penalized states that did not give the vote to freedmen, and most importantly, created new federal civil rights that could be protected by federal courts. It guaranteed the federal war debt and voided all Confederate war debts. Johnson unsuccessfully sought to block ratification of the amendment.

The moderates' effort to compromise with Johnson had failed and an all-out political war broke out between the Republicans (both radical and moderate) on one side, and on the other Johnson and his allies in the Democratic party in the North, and the conservative groupings in the South. The decisive battle was the election of 1866, in which the Southern states were not allowed to vote. Johnson campaigned vigorously, undertaking a public speaking tour of the north that was known as the "Swing Around the Circle"; the tour proved politically disastrous, with Johnson widely ridiculed and occasionally engaging in hostile arguments with his audiences.[24] The Republicans won by a landslide and took full control of Reconstruction.

Historian James Ford Rhodes explained Johnson's inability to engage in serious negotiations:

As Senator Charles Sumner shrewdly said, "the President himself is his own worst counselor, as he is his own worst defender." Johnson acted according to his nature. He had intellectual force, but it worked in a groove. Obstinate, rather than firm, it undoubtedly seemed to him that following counsel and making concessions were a display of weakness. At all events from his December message to the veto of the Civil Rights bill, he did not yield to Congress. The moderate senators and representatives, who constituted a majority of the Union party, asked him for only a slight compromise. Their action was really an entreaty that he would unite with them to preserve Congress and the country from the policy of the radicals.

The two projects which Johnson had most at heart were the speedy admission of the Southern senators and representatives to Congress and the relegation of the question of 'negro suffrage' to the States themselves. Johnson, shrinking from the imposition on these communities of the franchise for the colored people, took an unyielding position regarding matters involving no vital principle and did much to bring it about. His quarrel with Congress prevented the readmission into the Union on generous terms of the members of the late Confederacy. For the quarrel and its unhappy results, Johnson's lack of imagination and his inordinate sensitiveness to political gadflies were largely responsible.

Johnson sacrificed two important objects to petty considerations. His pride of opinion and his desire to win, blinded him to the real welfare of the South and of the whole country.[25]

Impeachment

First attempt

There were two attempts to remove President Andrew Johnson from office. The first occurred in the fall of 1867. On November 21, 1867, the House Judiciary committee produced a bill of impeachment that consisted of a vast collection of complaints against him. After a furious debate, a formal vote was held in the House of Representatives on December 5, 1867, which failed 57–108.[26]

Second attempt

Johnson notified Congress that he had removed Edwin Stanton as Secretary of War and was replacing him in the interim with Adjutant-General Lorenzo Thomas. Johnson had wanted to replace Stanton with former general Ulysses S. Grant, who refused to accept the position. This violated the Tenure of Office Act, a law enacted by Congress in March 1867 over Johnson's veto, specifically designed to protect Stanton.[27] Johnson had vetoed the act, claiming it was unconstitutional. The act said, "...every person holding any civil office, to which he has been appointed by and with the advice and consent of the Senate ... shall be entitled to hold such office until a successor shall have been in like manner appointed and duly qualified," thus removing the president's previous unlimited power to remove any of his cabinet members at will. Years later in the case Myers v. United States in 1926, the Supreme Court ruled that such laws were indeed unconstitutional.[28]

The Senate and House entered into debate. Thomas attempted to move into the war office, for which Stanton had Thomas arrested. Three days after Stanton's removal, the House impeached Johnson for intentionally violating the Tenure of Office Act.

On March 5, 1868, a court of impeachment was constituted in the Senate to hear charges against the president. William M. Evarts served as his counsel. Eleven articles were set out in the resolution, and the trial before the Senate lasted almost three months. Johnson's defense was based on a clause in the Tenure of Office Act stating that the then-current secretaries would hold their posts throughout the term of the president who appointed them. Since Lincoln had appointed Stanton, it was claimed, the applicability of the act had already run its course.

A Harper's Weekly cartoon gives a humorous breakdown of "the situation". Secretary of War Edwin Stanton aims a cannon labeled "Congress" on the side at President Johnson and Lorenzo Thomas to show how Stanton was using congress to defeat the president and his unsuccessful replacement. He also holds a rammer marked "Tenure of Office Bill" and cannon balls on the floor are marked "Justice". Ulysses S. Grant and an unidentified man stand to Stanton's left.

There were three votes in the Senate. One came on May 16 for the 11th article of impeachment, which included many of the charges contained in the other articles, and two on May 26 for the second and third articles, after which the trial adjourned. On all three occasions, 35 senators voted "guilty" and 19 "not guilty", thus falling short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction in impeachment trials by a single vote. A decisive role was played by seven Republican senators - William Pitt Fessenden, Joseph S. Fowler, James W. Grimes, John B. Henderson, Lyman Trumbull, Peter G. Van Winkle and Edmund G. Ross of Kansas, who provided the decisive vote,[29] - who were disturbed by how the proceedings had been manipulated to give a one-sided presentation of the evidence, in defiance of their party and public opinion, voted against conviction.[30]

Christmas Day amnesty for Confederates

One of Johnson's last significant acts was granting unconditional amnesty to all Confederates on Christmas Day, December 25, 1868, after the election of U.S. Grant to succeed him, but before Grant took office in March 1869. Earlier amnesties, requiring signed oaths and excluding certain classes of people, had been issued by Lincoln and by Johnson.

Administration and Cabinet

| The A. Johnson cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Andrew Johnson | 1865–1869 |

| Vice President | None | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Hugh McCulloch | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of War | Edwin M. Stanton | 1865–1868, replaced ad interim by Ulysses Grant before being reinstated by Congress in Jan 1868 |

| John M. Schofield | 1868–1869 | |

| Attorney General | James Speed | 1865–1866 |

| Henry Stanberry | 1866–1868 | |

| William M. Evarts | 1868–1869 | |

| Postmaster General | William Dennison | 1865–1866 |

| Alexander W. Randall | 1866–1869 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1865–1869 |

| Secretary of the Interior | John P. Usher | 1865 |

| James Harlan | 1865–1866 | |

| Orville H. Browning | 1866–1869 | |

Judicial appointments

Johnson appointed only nine federal judges during his presidency, all to United States district courts:

| Judge | Court | Began active service |

Ended active service |

| Samuel Blatchford | S.D.N.Y. | May 3, 1867[31] | March 4, 1878 |

| George Seabrook Bryan | D.S.C. | March 12, 1866 | September 1, 1886 |

| Daniel Clark | D.N.H. | July 27, 1866 | January 2, 1891 |

| Elmer Scipio Dundy | D. Neb. | April 9, 1868 | October 28, 1896 |

| John Erskine | N.D. Ga. S.D. Ga. |

July 10, 1865[32] | April 25, 1882 December 1, 1883 |

| Edward Fox | D. Me. | May 31, 1866 | December 14, 1881 |

| Robert Andrews Hill | S.D. Miss. N.D. Miss. |

May 1, 1866 | August 1, 1891 |

| Charles Taylor Sherman | N.D. Ohio | March 2, 1867 | November 25, 1872 |

Andrew Johnson is one of only four presidents[33] who did not have an opportunity to appoint a judge to serve on the Supreme Court. In April, 1866 he nominated Henry Stanbery to fill the vacancy left with the death of John Catron, but the Republican Congress eliminated the seat.

States admitted to the Union

- Nebraska – March 1, 1867

Foreign policy

Johnson forced the French out of Mexico by sending an army to the border and issuing an ultimatum. The French withdrew in 1867, and the government they supported quickly collapsed. Secretary of State Seward negotiated the purchase of Alaska from Russia on April 9, 1867 for $7.2 million. This is equivalent to $157 million in present day terms.[34] Critics sneered at "Seward's Folly" and "Seward's Icebox" and "Icebergia." Seward also negotiated to purchase the Danish West Indies, but the Senate refused to approve the purchase in 1867 (it eventually happened in 1917). The Senate likewise rejected Seward's arrangement with the United Kingdom to arbitrate the Alabama Claims.

The U.S. experienced tense relations with the United Kingdom and its colonial government in Canada in the aftermath of the war. Lingering resentment over the perception of British sympathy toward the Confederacy resulted in Johnson initially turning a blind eye towards a series of armed incursions by Irish-American civil war veterans into British territory in Canada, named the Fenian Raids.[35] Eventually, Johnson ordered the Fenians disarmed and barred from crossing the border, but his hesitant reaction to the crisis helped motivate the movement toward Canadian Confederation.[35]

Johnson's purchase of Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867 is believed to be his most important foreign policy action. The idea and implementation is credited to Seward as Secretary of State, but Johnson approved the plan. Gold was not discovered in Alaska until 1880, thirteen years after the purchase and five years after Johnson's death, and oil was not discovered until 1968.

Post-presidency

Johnson was an unsuccessful candidate for election to the United States Senate from Tennessee in 1868 and to the House of Representatives in 1872. However, in 1874 the Tennessee legislature did elect him to the U.S. Senate. Johnson served from March 4, 1875, until his death from a stroke near Elizabethton, Tennessee, on July 31 that year. In his first speech since returning to the Senate, which was also his last, Johnson spoke about political turmoil in Louisiana.[36] His passion aroused a standing ovation from many of his fellow senators who had once voted to remove him from the presidency.[37] He is the only former president to serve in the Senate.[36]

Johnson was buried in the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery, Greeneville, Tennessee, with his body wrapped in an American flag and a copy of the U.S. Constitution placed under his head, according to his wishes. The cemetery is now part of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site.

Historians' changing views on Andrew Johnson

Views on President Johnson changed over time, depending on historians' perception of Reconstruction. The widespread denunciation of Reconstruction following the compromise of 1877 resulted in Johnson being portrayed in a favorable light. By the 1930s a series of favorable biographies enhanced his prestige.[38]. Furthermore, a Beardian School (named after Charles Beard and typified by Howard K. Beale) argued that the Republican Party in the 1860s was a tool of corrupt business interests, and that Johnson stood for the people. They rated Johnson "near great", but have later changed their minds[clarification needed], rating Johnson "a flat failure".[39]

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s brought a new perspective on Reconstruction, which was increasingly seen as a noble effort to build an interracial nation.[39][40] Beginning with W. E. B. Du Bois' Black Reconstruction, first published in 1935, historians noted African American efforts to establish public education and welfare institutions, gave muted praise for Republican efforts to extend suffrage and provide other social institutions, and excoriated Johnson for siding with the opposition to extending basic rights to former slaves.[39] In this vein, Eric Foner denounced Johnson as a "fervent white supremacist" who foiled Reconstruction[39], whereas Sean Wilentz wrote that Johnson "actively sided with former Confederates" in his attempts to derail it.[41] Accordingly, Johnson is nowadays among those commonly mentioned among the worst presidents in U.S. history.[40]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- United States presidential election, 1864

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- Tennessee Johnson

Bibliography

- Howard K. Beale, The Critical Year. A Study of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1930). ISBN 0804410852

- Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1999). ISBN 0393319822

- Boulard, Garry, "The Swing Around the Circle—Andrew Johnson and the Train Ride that Destroyed a Presidency" (2008) ISBN 978-1-4401-0239-4

- Albert E. Castel, The Presidency of Andrew Johnson (1979). ISBN 0700601902

- D. M. DeWitt, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson (1903).

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 'The Transubstantiation of a Poor White' in Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward the History of the Part Which Black People Have Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880 (1935). ISBN 0527252808.

- W. A. Dunning, Essays on the Civil War and Reconstruction (New York, 1898)

- W. A. Dunning, Reconstruction, Political and Economic (New York, 1907) online edition

- Foster, G. Allen, Impeached: The President who almost lost his job (New York, 1964).

- Eric L. McKitrick, Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (1961). ISBN 0-19-505707-4

- Martin E. Mantell; Johnson, Grant, and the Politics of Reconstruction (1973)

- Hatfield, Mark O., with the Senate Historical Office, Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993.(U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997), p. 219

- Howard Means, The Avenger Takes His Place: Andrew Johnson and the 45 Days That Changed the Nation (New York, 2006)

- Milton; George Fort. The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson and the Radicals (1930) online edition

- Patton; James Welch. Unionism and Reconstruction in Tennessee, 1860–1869 (1934) online edition

- Rhodes; James Ford History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896 Volume: 6. 1920. Pulitzer prize.

- Schouler, James. History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution vol. 7. 1865–1877. The Reconstruction Period (1917)

- Sledge, James L. III. "Johnson, Andrew" in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. (2000)

- Stewart, David, O. Impeached: the Trial of President Andrew Jackson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (2009) Simon and Schuster, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4165-4749-5.

- Lloyd P. Stryker, Andrew Johnson: A Study in Courage (1929). ISBN 0-403-01231-7 online edition

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989). ISBN 0-393-31742-0 online edition

- Winston; Robert W. Andrew Johnson: Plebeian and Patriot (1928) online edition

Primary sources

- Ralph W. Haskins, LeRoy P. Graf, and Paul H. Bergeron et al., eds. The Papers of Andrew Johnson 16 volumes; University of Tennessee Press, (1967–2000). ISBN 1572330910. Includes all letters and speeches by Johnson, and many letters written to him. Complete to 1875.

- Newspaper clippings, 1865–1869

- Series of Harper's Weekly articles covering the impeachment controversy and trial

- Johnson's obituary, from the New York Times

Notes

- ^ "American President: Andrew Johnson: Family Life". Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Milton, George Fort (1930). The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson And The Radicals. New York: Coward-McCann. p. 80. ISBN 1417916583. OCLC 739916.

As for my religion, it is the doctrine of the Bible, as taught and practiced by Jesus Christ.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h 'Andrew Johnson', Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Hall, Kermit (2005). American Legal History (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 259–260. ISBN 0-19-516225-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Trefousse, Hans Louis. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1997), p. 338–339.

- ^ 14 according to Britannica, 10 according to Karin L Zipf

- ^ Laurens Historic District historical marker

- ^ Karin L Zipf. Labor Of Innocents: Forced Apprenticeship in North Carolina, 1715–1919 (2005) pp 8–9

- ^ a b c d "The Andrew Johnson Collection". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Timeline of President Andrew Johnson's Life (PDF) from the Web site of the president Andrew Johnson Museum and Library at Tusculum College

- ^ a b c d Biography of Andrew Johnson– www.whitehouse.gov

- ^

- United States Congress. "Andrew Johnson (id: J000116)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ^ World Book

- ^ Sledge pg. 1071–1072

- ^ Patton p 126

- ^ "Tennessee Recalls Emancipation, Segregation", National Public Radio

- ^ Trefousse p. 198

- ^ Complete list of U.S. presidents

- ^ Milton 183

- ^ Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989)

- ^ "Memoirs of W.W. Holden: Electronic Edition".

- ^ Rhodes, History 6:68

- ^ Trefousse pg. 236. Online reference to the quote available at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/grant/peopleevents/e_impeach.html

- ^ Trefousse 1999

- ^ Andrew Johnson Cleveland Speech (September 3, 1866)

- ^ Rhodes, History 6:74

- ^ Trefousse, 1989 pages 302–3

- ^ Tenure of office act– Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Tenure of office act– Britannica Concise

- ^ "The Trial of Andrew Johnson, 1868".

- ^ "Andrew Johnson Trial: The Consciences of Seven Republicans Save Johnson".

- ^ Recess appointment; formally nominated on July 13, 1867, confirmed by the United States Senate on July 16, 1867, and received commission on July 16, 1867.

- ^ Recess appointment; formally nominated on December 20, 1865, confirmed by the United States Senate on January 22, 1866, and received commission on January 22, 1866.

- ^ The other three presidents are William Henry Harrison, Zachary Taylor and Jimmy Carter.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b The Fenian Raids

- ^ a b United States Senate: Death of Andrew Johnson

- ^ Andrew Johnson. American-Presidents.com. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- ^ Highly favorable were Winston (1928), Stryker (1929), Milton (1930), and Claude Bowers, The Tragic Era (1929).

- ^ a b c d He's The Worst Ever, Eric Foner, Washington Post, December 3, 2006; accessed December 15, 2008.

- ^ a b The 10 Worst Presidents: No. 3 Andrew Johnson (1865-1869), Jay Tolson, U.S. News & World Report, February 16, 2007; accessed December 15, 2008.

- ^ The Worst President in History?, Sean Wilentz, Rolling Stone, April 21, 2006; accessed December 15, 2008.

External links

- Works by Andrew Johnson at Project Gutenberg

- The Impeachment trial of President Johnson as reported in Harper's Monthly Magazine April 1868

- Obituary, NY Times, August 1, 1875, Andrew Johnson Dead

- Articles of Impeachment

- White House Biography

- Vice Presidential biography. From the Senate Historical Office.

- Mr. Lincoln's White House: Andrew Johnson

- Andrew Johnson Cleveland Speech (September 3, 1866)

- Congressional Globe transcript of Johnsons inaugural address

- Speeches of Andrew Johnson : President of the United States 1866 collection at archive.org

- Andrew Johnson's 200th Birthday Celebration site at DiscoverGreeneville.com

- Andrew Johnson: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Andrew Johnson Papers, 1846-1875

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of Governor Andrew Johnson, 1853-1857

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of (Military) Governor Andrew Johnson, 1862-1865

- United States Congress. "Andrew Johnson (id: J000116)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-03-02

- Essay on Andrew Johnson and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Paper comparing the impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton

- Andrew Johnson

- United States presidential candidates, 1860

- United States presidential candidates, 1868

- Union Army generals

- Governors of Tennessee

- United States Senators from Tennessee

- Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- Tennessee State Senators

- Burials in Tennessee

- Deaths from stroke

- Members of the Tennessee House of Representatives

- Mayors of places in Tennessee

- Tennessee city councillors

- People from Raleigh, North Carolina

- Union political leaders

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Tennessee Democrats

- People of Tennessee in the American Civil War

- Impeached United States officials

- Scots-Irish Americans

- People of North Carolina in the American Civil War

- People of American Reconstruction

- People from Greeneville, Tennessee

- People from Greene County, Tennessee

- 1808 births

- 1875 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of the United States

- 19th-century vice presidents of the United States