History of Gilgit-Baltistan: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("Weightman" from Gilgit-Baltistan) |

→End of the princely state: I don't see the need for an extended quote here; it is accepted that the population did not favour India; whether they favoured Pakistan cannot be decided by a single quote |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==End of the princely state== |

==End of the princely state== |

||

Stories of communal violence by Hindus and Sikhs against Muslims in Punjab reached Gilgit and inflamed passions against the small Hindu and Sikh minorities in Gilgit. On 26 October 1947, [[Maharaja Hari Singh]] of Jammu and Kashmir, faced with a tribal invasion from Pakistan, signed the [[Instrument of Accession]], joining India. |

Stories of communal violence by Hindus and Sikhs against Muslims in Punjab reached Gilgit and inflamed passions against the small Hindu and Sikh minorities in Gilgit. On 26 October 1947, [[Maharaja Hari Singh]] of Jammu and Kashmir, faced with a tribal invasion from Pakistan, signed the [[Instrument of Accession]], joining India. |

||

Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India.{{sfn|Bangash|2010|p=128|ps=: [Ghansara Singh] wrote to the prime minister of Kashmir: 'in case the State accedes to the Indian Union, the Gilgit province will go to Pakistan', but no action was taken on it, and in fact Srinagar never replied to any of his messages.}} The Muslims of the Frontier Districts Province (modern day Gilgit-Baltistan) had wanted to join [[Pakistan]].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com.au/books?id=0cPjAAAAQBAJ&pg=PT14&dq=muslims+in+jammu+province+and+frontier+province+wanted+to+join+pakistan+snedden&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjdh8XLtZPRAhVGwLwKHc-kCngQ6AEIGTAA#v=onepage&q=muslims%20in%20jammu%20province%20and%20frontier%20province%20wanted%20to%20join%20pakistan%20snedden&f=false|title=Kashmir-The Untold Story|last=Snedden|first=Christopher|publisher=HarperCollins Publishers India|year=2013|isbn=9789350298985|location=|pages=|quote=Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted J&K to join Pakistan.|via=}}</ref> Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the [[Gilgit Scouts]], mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the Governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless ''coup d'etat'' was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name "Datta Khel", which was also joined by a rebellious section of the Jammu and Kashmir 6th Infantry under [[Col Mirza Hassan Khan|Mirza Hassan Khan]]. Brown ensured that the treasury was secured and minorities were protected. A provisional government (''Aburi Hakoomat'') was established by the Gilgit locals with Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. However, Major Brown had already telegraphed [[Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan]] asking Pakistan to take over. The Pakistani political agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit.{{sfn|Schofield|2003|pp=63–64}}<ref name=accessions>{{harvnb|Bangash|2010}}</ref> Brown outmaneuvered the pro-Independence group and secured the approval of the mirs and rajas for accession to Pakistan. Browns's actions surprised the British Government.<ref name="Schofield2000">{{cite book|author=Victoria Schofield|title=Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rkTetMfI6QkC&pg=PA64|year=2000|publisher=I.B.Tauris|isbn=978-1-86064-898-4|pages=63–64}}</ref> According to Brown, |

|||

{{quote|Alam replied [to the locals], "you are a crowd of fools led astray by a madman. I shall not tolerate this nonsense for one instance... And when the Indian Army starts invading you there will be no use screaming to Pakistan for help, because you won't get it."... The provisional government faded away after this encounter with Alam Khan, clearly reflecting the flimsy and opportunistic nature of its basis and support.{{sfn|Bangash|2010|p=133}}}} |

{{quote|Alam replied [to the locals], "you are a crowd of fools led astray by a madman. I shall not tolerate this nonsense for one instance... And when the Indian Army starts invading you there will be no use screaming to Pakistan for help, because you won't get it."... The provisional government faded away after this encounter with Alam Khan, clearly reflecting the flimsy and opportunistic nature of its basis and support.{{sfn|Bangash|2010|p=133}}}} |

||

Revision as of 20:16, 28 April 2018

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Gilgit-Baltistan is an administrative territory of Pakistan, that borders the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, Azad Kashmir to the southwest, Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan to the northwest, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China to the north, and the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir to the south and southeast.

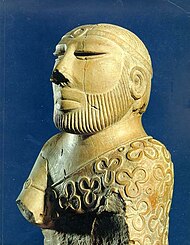

Rock art and petroglyphs

There are more than 50,000 pieces of rock art (petroglyphs) and inscriptions all along the Karakoram Highway in Gilgit Baltistan, concentrated at ten major sites between Hunza and Shatial. The carvings were left by various invaders, traders, and pilgrims who passed along the trade route, as well as by locals. The earliest date back to between 5000 and 1000 BCE, showing single animals, triangular men and hunting scenes in which the animals are larger than the hunters. These carvings were pecked into the rock with stone tools and are covered with a thick patina that proves their age. The ethnologist Karl Jettmar has pieced together the history of the area from various inscriptions and recorded his findings in Rock Carvings and Inscriptions in the Northern Areas of Pakistan[1] and the later released Between Gandhara and the Silk Roads - Rock Carvings Along the Karakoram Highway.[2]

British Raj

It took a long time for the Maharajahs Ghulab Singh and Ranbir Singh to extend their writ over Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, and not until 1870 did they assert their authority over Gilgit town. The grip of the Jammu and Kashmir government over this area was tenuous. The Indian government undertook administrative reforms in 1885 and created Gilgit Agency in 1889 as a way for the British to secure the region as a buffer from the Russians. As a result of this Great Game, with British fear of Russian activities in Chinese Sinkiang increasing, in 1935 the Gilgit Agency was expanded by the Maharajah Hari Singh leasing the Gilgit Wazarat to the government of India for a period of sixty years and for an amount of 75,000Rs. This gave the British political agent complete control of defence, communications and foreign relations while the Kashmiri state retained civil administration and the British retained control of defence and foreign affairs.[3]

After World War II British influence started declining. British despite decline in its rule, handled the situation cleverly and gave two options to the states in British Raj under their rule to join any of the two emerging states, India and Pakistan.[citation needed] In 1947, Mountbatten decided to terminate the lease of Gilgit by Kashmir to the British. Scholar Yaqoob Khan Bangash opines that the motive for this is unclear.[4]

The people of Gilgit thought themselves to be ethnically different from the Kashmiris and resented being under Kashmir state rule. Gilgit was also one of the most backward areas of the Kashmir state. Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, believed that the British handover of Gilgit to Kashmir was a huge mistake.[5]

Brown recounts that when he met the scouts ''they indirectly made it clear how they despised and hated Kashmir and everything connected with it, how happy and content they had been under the British rule, and how they considered they had been betrayed by the British in the unconditional handing over of their country to Kashmir''.[5]

Taking advantage of the situation the populace of Gilgit-Baltistan started revolting, the people of Ghizer were first to raise the flag of revolution, and gradually the masses of entire region stood up against the rule of Maharaja, again British played an important role in war of independence of Gilgit-Baltistan.[6][unreliable source?]

End of the princely state

Stories of communal violence by Hindus and Sikhs against Muslims in Punjab reached Gilgit and inflamed passions against the small Hindu and Sikh minorities in Gilgit. On 26 October 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, faced with a tribal invasion from Pakistan, signed the Instrument of Accession, joining India.

Gilgit's population did not favour the State's accession to India.[7] The Muslims of the Frontier Districts Province (modern day Gilgit-Baltistan) had wanted to join Pakistan.[8] Sensing their discontent, Major William Brown, the Maharaja's commander of the Gilgit Scouts, mutinied on 1 November 1947, overthrowing the Governor Ghansara Singh. The bloodless coup d'etat was planned by Brown to the last detail under the code name "Datta Khel", which was also joined by a rebellious section of the Jammu and Kashmir 6th Infantry under Mirza Hassan Khan. Brown ensured that the treasury was secured and minorities were protected. A provisional government (Aburi Hakoomat) was established by the Gilgit locals with Raja Shah Rais Khan as the president and Mirza Hassan Khan as the commander-in-chief. However, Major Brown had already telegraphed Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan asking Pakistan to take over. The Pakistani political agent, Khan Mohammad Alam Khan, arrived on 16 November and took over the administration of Gilgit.[9][10] Brown outmaneuvered the pro-Independence group and secured the approval of the mirs and rajas for accession to Pakistan. Browns's actions surprised the British Government.[11] According to Brown,

Alam replied [to the locals], "you are a crowd of fools led astray by a madman. I shall not tolerate this nonsense for one instance... And when the Indian Army starts invading you there will be no use screaming to Pakistan for help, because you won't get it."... The provisional government faded away after this encounter with Alam Khan, clearly reflecting the flimsy and opportunistic nature of its basis and support.[12]

The provisional government lasted 16 days. The provisional government lacked sway over the population. The Gilgit rebellion did not have civilian involvement and was solely the work of military leaders, not all of whom had been in favor of joining Pakistan, at least in the short term. Historian Ahmed Hasan Dani mentions that although there was lack of public participation in the rebellion, pro-Pakistan sentiments were intense in the civilian population and their anti-Kashmiri sentiments were also clear.[13] According to various scholars, the people of Gilgit as well as those of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin, Punial, Hunza and Nagar joined Pakistan by choice.[14][15][16][17][18]

After taking control of Gilgit, the Gilgit Scouts along with Azad irregulars moved towards Baltistan and Ladakh and captured Skardu by May 1948. They successfully blocked the Indian reinforcements and subsequently captured Dras and Kargill as well, cutting off the Indian communications to Leh in Ladakh. The Indian forces mounted an offensive in Autumn 1948 and recaptured all of Kargil district. Baltistan region, however, came under Gilgit control.[19][20]

On 1 January 1948, India took the issue of Jammu and Kashmir to the United Nations Security Council. In April 1948, the Council passed a resolution calling for Pakistan to withdraw from all of Jammu and Kashmir and then India was to reduce its forces to the minimum level, following which a plebiscite would be held to ascertain the people's wishes.[21] However, no withdrawal was ever carried out, India insisting that Pakistan had to withdraw first and Pakistan contending that there was no guarantee that India would withdraw afterwards.[22] Gilgit-Baltistan and a western portion of the state called Azad Jammu and Kashmir) have remained under the control of Pakistan since then.[23]

Part of Pakistan

While the residents of Gilgit-Baltistan expressed a desire to join Pakistan after gaining independence from Maharaja Hari Singh, Pakistan declined to merge the region into itself because of the territory's link to Jammu and Kashmir.[17] For a short period after joining Pakistan, Gilgit-Baltistan was governed by Azad Kashmir if only "theoretically, but not practically" through its claim of being an alternative government for Jammu and Kashmir.[24] In 1949, the Government of Azad Kashmir handed administration of the area to the federal government via the Karachi Agreement, on an interim basis which gradually assumed permanence. According to Indian journalist Sahni, this is seen as an effort by Pakistan to legitimize its rule over Gilgit-Baltistan.[25]

There were two reasons why administration was transferred from Azad Kashmir to Pakistan: (1) the region was inaccessible to Azad Kashmir and (2) because both the governments of Azad Kashmir and Pakistan knew that the people of the region were in favour of joining Pakistan in a potential referendum over Kashmir's final status.[17]

According to the International Crisis Group, the Karachi Agreement is highly unpopular in Gilgit-Baltistan because Gilgit-Baltistan was not a party to it even while its fate was being decided upon.[26]

From then until 1990s, Gilgit-Baltistan was governed through the colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulations, which treated tribal people as "barbaric and uncivilised," levying collective fines and punishments.[27][28] People had no right to legal representation or a right to appeal.[29][28] Members of tribes had to obtain prior permission from the police to travel to any location and had to keep the police informed about their movements.[30][31] There was no democratic set-up for Gilgit-Baltistan during this period. All political and judicial powers remained in the hands of the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and Northern Areas (KANA). The people of Gilgit-Baltistan were deprived of rights enjoyed by citizens of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir.[32]

A primary reason for this state of affairs was the remoteness of Gilgit-Baltistan. Another factor was that the whole of Pakistan itself was deficient in democratic norms and principles, therefore the federal government did not prioritise democratic development in the region. There was also a lack of public pressure as an active civil society was absent in the region, with young educated residents usually opting to live in Pakistan's urban centers instead of staying in the region.[32]

In 1970 the two parts of the territory, viz., the Gilgit Agency and Baltistan, were merged into a single administrative unit, and given the name "Northern Areas".[33] The Shaksgam tract was ceded by Pakistan to China following the signing of the Sino-Pakistani Frontier Agreement in 1963.[34][35] In 1969, a Northern Areas Advisory Council (NAAC) was created, later renamed to Northern Areas Council (NAC) in 1974 and Northern Areas Legislative Council (NALC) in 1994. But it was devoid of legislative powers. All law-making was concentrated in the KANA Ministry of Pakistan. In 1994, a Legal Framework Order (LFO) was created by the KANA Ministry to serve as the de facto constitution for the region.[36][37]

In 1984 the territory's importance shot up on the domestic level with the opening of the Karakoram Highway and the region's population came to be more connected with mainland Pakistan. With the improvement in connectivity, the local population availed education opportunities in the rest of Pakistan.[38] Improved connectivity also allowed the political parties of Pakistan and Azad Kashmir to setup local branches, raise political awareness in the region, and these Pakistani political parties have played a 'laudable role' in organising a movement for democratic rights among the residents of Gilgit-Baltistan.[32]

In the late 1990s, the President of Al-Jihad Trust filed a petition in the Supreme Court of Pakistan to determine the legal status of Gilgit-Baltistan. In its judgement of 28 May 1999, the Court directed the Government of Pakistan to ensure the provision of equal rights to the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, and gave it six months to do so. Following the Supreme Court decision the government took several steps to devolve power to the local level. However, in several policy circles the point was raised that the Pakistani government was helpless to comply with the court verdict because of the strong political and sectarian divisions in Gilgit-Baltistan and also because of the territory's historical connection with the still disputed Kashmir region and this prevented the determination of Gilgit-Baltistan's real status.[39]

A position of 'Deputy Chief Executive' was created to act as the local administrator, but the real powers still rested with the 'Chief Executive', who was the Federal Minister of KANA. "The secretaries were more powerful than the concerned advisors," in the words of one commentator. In spite of various reforms packages over the years, the situation is essentially unchanged.[40] Meanwhile, public rage in Gilgit-Baltistan is "growing alarmingly." Prominent "antagonist groups" have mushroomed protesting the absence of civic rights and democracy.[41] Pakistan government has been debating the grant of a provincial status to Gilgit-Baltistan.[42]

Gilgit Baltistan, which was most recently known as the Northern Areas, presently consists of ten districts,[43] has a population approaching two million, has an area of approximately 28,000 square miles (73,000 km2), and shares borders with China, Afghanistan, and India. The local Northern Light Infantry is the army unit that participated in the 1999 Kargil conflict. More than 500 soldiers were believed to have been killed and buried in the Northern Areas in that action.[44] Lalak Jan, a soldier from Yasin Valley, was awarded Pakistan's most prestigious medal, the Nishan-e-Haider, for his courageous actions during the Kargil conflict.

Self-governing status and present-day Gilgit Baltistan

On 29 August 2009, the Gilgit Baltistan Empowerment and Self-Governance Order, 2009, was passed by the Pakistani cabinet and later signed by the President of Pakistan. The order granted self-rule to the people of the former Northern Areas, now renamed Gilgit Baltistan, by creating, among other things, an elected legislative assembly.

There has been an uplift in the self-identification of this territory's inhabitants through the name change but it has still left the region's constitutional status within Pakistan undefined. The 2009 reform has failed to answer the people's demands for citizenship rights. According to Antia Mato Bouzas, the move was the Pakistani government's compromise between its official stand on Kashmir and demands of a territory where the majority of people may have pro-Pakistan sentiments.[45]

There has been some criticism and opposition to this move in India and Gilgit Baltistan region of Pakistan.[46][47]

Gilgit Baltistan United Movement while rejecting the new package demanded that an independent and autonomous legislative assembly for Gilgit Baltistan should be formed with the installation of local authoritative government as per the UNCIP resolutions, where the people of Gilgit Baltistan will elect their president and the prime minister.[48]

In early September 2009, Pakistan signed an agreement with the People's Republic of China for a mega energy project in Gilgit–Baltistan which includes the construction of a 7,000-megawatt dam at Bunji in the Astore District.[49] This also resulted in protest from India, although Indian concerns were immediately rejected by Pakistan, which claimed that the Government of India has no locus standi in the matter, effectively ignoring the validity of the princely state's Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947.

On 29 September 2009, the Prime Minister, while addressing a huge gathering in Gilgit–Baltistan, announced a multi-billion rupee development package aimed at the socio-economic uplifting of people in the area. Development projects will include the areas of education, health, agriculture, tourism and the basic needs of life.[50][51]

References

- ^ "Rock Carvings and Inscriptions along the Karakorum Highway (Pakistan) - - a brief introduction". Archived from the original on 2011-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Between gandhara and the silk roads". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 121, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ^ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 124, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ^ a b Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 125-126, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ^ "History, movements and freedom".

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 128: [Ghansara Singh] wrote to the prime minister of Kashmir: 'in case the State accedes to the Indian Union, the Gilgit province will go to Pakistan', but no action was taken on it, and in fact Srinagar never replied to any of his messages.

- ^ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir-The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

Similarly, Muslims in Western Jammu Province, particularly in Poonch, many of whom had martial capabilities, and Muslims in the Frontier Districts Province strongly wanted J&K to join Pakistan.

- ^ Schofield 2003, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Bangash 2010

- ^ Victoria Schofield (2000). Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-86064-898-4.

- ^ Bangash 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 132, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ^ Yaqoob Khan Bangash (2010) Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1, 137, DOI: 10.1080/03086530903538269

- ^ Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (9 January 2016). "Gilgit-Baltistan—part of Pakistan by choice". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

Nearly 70 years ago, the people of the Gilgit Wazarat revolted and joined Pakistan of their own free will, as did those belonging to the territories of Chilas, Koh Ghizr, Ishkoman, Yasin and Punial; the princely states of Hunza and Nagar also acceded to Pakistan. Hence, the time has come to acknowledge and respect their choice of being full-fledged citizens of Pakistan.

- ^ Chitralekha Zutshi (2004). Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 309–. ISBN 978-1-85065-700-2.

- ^ a b c Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Sokefeld, Martin (November 2005), "From Colonialism to Postcolonial Colonialism: Changing Modes of Domination in the Northern Areas of Pakistan", The Journal of Asian Studies, 64 (4): 939–973, doi:10.1017/S0021911805002287

- ^ Schofield 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Bajwa, Farooq (2013), From Kutch to Tashkent: The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965, Hurst Publishers, pp. 22–24, ISBN 978-1-84904-230-7

- ^ Bose, Tapan K. (2004). Raṇabīra Samāddāra (ed.). Peace Studies: An Introduction To the Concept, Scope, and Themes. Sage. p. 324. ISBN 978-0761996606.

- ^ Varshney, Ashutosh (1992), "Three Compromised Nationalisms: Why Kashmir has been a Problem" (PDF), in Raju G. C. Thomas (ed.), Perspectives on Kashmir: the roots of conflict in South Asia, Westview Press, p. 212, ISBN 978-0-8133-8343-9

- ^ Warikoo, Kulbhushan (2008). Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-0415468398.

- ^ Snedden 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Sahni 2009, p. 73.

- ^ International Crisis Group 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Bansal 2007, p. 60.

- ^ a b From the fringes: Gilgit-Baltistanis silently observe elections, Dawn, 1 May 2013.

- ^ Priyanka Singh 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Raman 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Behera 2007, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Weightman, Barbara A. (2 December 2005). Dragons and Tigers: A Geography of South, East, and Southeast Asia (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-471-63084-5.

- ^ Chellaney, Brahma (2011). Water: Asia's New Battleground. Georgetown University Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-58901-771-9.

- ^ "China's Interests in Shaksgam Valley". Sharnoff's Global Views.

- ^ International Crisis Group 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 25-26.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud 2008, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Ershad Mahmud, Gilgit-Baltistan: A province or not, The News on Sunday, 24 January 2016.

- ^ Dividing governance: Three new districts notified in G-B, The Express Tribune, 5 February 2017.

- ^ [1] Special Report on Kargil", The Herald (Pakistan)

- ^ Antia Mato Bouzas (2012) Mixed Legacies in Contested Borderlands: Skardu and the Kashmir Dispute, Geopolitics, 17:4, 874, DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2012.660577

- ^ "The Gilgit–Baltistan bungle". The News International. 2009-09-10. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ Gilgit-Baltistan package termed an eyewash, Dawn, 2009-08-30 Archived May 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gilgit–Baltistan: GBUM Calls for Self-Rule Under UN Resolutions". UNPO. 2009-09-09. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ "Pakistan | Gilgit–Baltistan autonomy". Dawn.Com. 2009-09-09. Archived from the original on September 12, 2009. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Manzar Shigri (2009-11-12). "Pakistan's disputed Northern Areas go to polls". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ "Pakistani president signs Gilgit–Baltistan autonomy order _English_Xinhua". News.xinhuanet.com. 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- Sources

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

- Antia Mato Bouzas (2012) Mixed Legacies in Contested Borderlands: Skardu and the Kashmir Dispute, Geopolitics, 17:4, 867-886, DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2012.660577