Public Enemy

Public Enemy | |

|---|---|

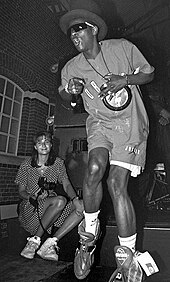

Public Enemy performing in 2000 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Long Island, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1985–present |

| Labels | |

| Members | Chuck D Flavor Flav DJ Lord Sammy Sam |

| Past members | Professor Griff Terminator X |

| Website | publicenemy |

Public Enemy is an American hip hop group formed by Chuck D and Flavor Flav on Long Island, New York, in 1985.[2][3] The group rose to prominence for their political messages including subjects such as American racism and the American media. Their debut album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, was released in 1987 to critical acclaim, and their second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988), was the first hip hop album to top The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop critics' poll.[4] Their next three albums, Fear of a Black Planet (1990), Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black (1991) and Muse Sick-n-Hour Mess Age (1994), were also well received. The group has since released twelve more studio albums, including the soundtrack to the 1998 sports-drama film He Got Game and a collaborative album with Paris, Rebirth of a Nation (2006).

Public Enemy has gone through many lineup changes over the years, with Chuck D and Flavor Flav remaining the only constant members. Co-founder Professor Griff left in 1989 but rejoined in 1998, before parting ways again some years later. DJ Lord also joined Public Enemy in 1998 as the replacement of the group's original DJ Terminator X. In 2020, it was announced that Flavor Flav had been fired from the group.[3] His firing was later revealed to be a publicity stunt that was called an April Fools' Day prank.[5][6] Public Enemy, without Flavor Flav, would also tour and record music under the name of Public Enemy Radio which consists of the lineup of Chuck D, Jahi, DJ Lord and the S1Ws.

Public Enemy's first four albums during the late 1980s and early 1990s were all certified either gold or platinum and were, according to music critic Robert Hilburn in 1998, "the most acclaimed body of work ever by a hip hop act".[7] Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine called them "the most influential and radical band of their time".[8] They were inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013.[9] They were honored with the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award at the 62nd Grammy Awards.

History

1985–1987: Formation and early years

Public Enemy was formed in 1985 by Carlton Ridenhour (Chuck D) and William Drayton (Flavor Flav), who met at Long Island's Adelphi University in the mid-1980s.[citation needed] Developing his talents as an MC with Flav while delivering furniture for his father's business, Chuck D and Spectrum City, as the group was called, released the record "Check Out the Radio", backed by "Lies", a social commentary—both of which would influence RUSH Productions' Run–D.M.C. and Beastie Boys.[10] Chuck D put out a tape to promote WBAU (the radio station where he was working at the time) and to fend off a local MC who wanted to battle him. He called the tape Public Enemy #1 because he felt like he was being persecuted by people in the local scene.[citation needed] This was the first reference to the notion of a public enemy in any of Chuck D's songs. The single was created by Chuck D with a contribution by Flavor Flav, though this was before the group Public Enemy was officially assembled.[citation needed] Around 1986, Bill Stephney, the former Program Director at WBAU, was approached by Sam Mulderrig, who offered Stephney a position with the label.[citation needed] Stephney accepted, and his first assignment was to help fledgling producer Rick Rubin sign Chuck D, whose song "Public Enemy Number One" Rubin had heard from Andre "Doctor Dré" Brown.[citation needed]

According to the book The History of Rap Music by Cookie Lommel, "Stephney thought it was time to mesh the hard-hitting style of Run DMC with politics that addressed black youth. Chuck recruited Spectrum City, which included Hank Shocklee, his brother Keith Shocklee, and Eric "Vietnam" Sadler, collectively known as the Bomb Squad, to be his production team and added another Spectrum City partner, Professor Griff, to become the group's Minister of Information. With the addition of Flavor Flav and another local mobile DJ named Terminator X, the group Public Enemy was born".[citation needed] According to Chuck, The S1W, which stands for Security of the First World, "represents that the black man can be just as intelligent as he is strong. It stands for the fact that we're not third-world people, we're first-world people; we're the original people".[11] Hank Shocklee came up with the name Public Enemy based on "underdog love and their developing politics" and the idea from Def Jam staffer Bill Stephney following the Howard Beach racial incident, Bernhard Goetz, and the death of Michael Stewart: "The Black man is definitely the public enemy."[12]

Public Enemy started out as opening act for the Beastie Boys during the latter's Licensed to Ill popularity,[citation needed] and in 1987 released their debut album Yo! Bum Rush the Show.[citation needed]

1987–1993: Mainstream success

The group's debut album, Yo! Bum Rush the Show, was released in 1987 to critical acclaim.[citation needed] In October 1987, music critic Simon Reynolds dubbed Public Enemy "a superlative rock band".[13] They released their second album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, in 1988, which performed better in the charts than their previous release, and included the hit single "Don't Believe the Hype" in addition to "Bring the Noise".[citation needed] It was the first hip hop album to be voted album of the year in The Village Voice's influential Pazz & Jop critics' poll.[4]

In 1989, the group returned to the studio to record their third album, Fear of a Black Planet, which continued their politically charged themes. The album was supposed to be released in late 1989,[14] but was pushed back to April 1990.[citation needed] It was the most successful of any of their albums and, in 2005, was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry.[citation needed] It included the singles "Welcome to the Terrordome", written after the band was criticized by Jews for Professor Griff's anti-semitic comments, "911 Is a Joke", which criticized emergency response units for taking longer to arrive at emergencies in the black community than those in the white community, and "Fight the Power".[15] "Fight the Power" is regarded as one of the most popular and influential songs in hip hop history.[16] It was the theme song of Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing.

The group's fourth album, Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black, continued this trend, with songs like "Can't Truss It", which addressed the history of slavery and how the black community can fight back against oppression; "I Don't Wanna be Called Yo Nigga", a track that takes issue with the use of the word nigga outside of its original derogatory context.[citation needed] The album also included the controversial song and video "By the Time I Get to Arizona", which chronicled the black community's frustration that some US states did not recognize Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday as a national holiday. The video featured members of Public Enemy taking out their frustrations on politicians in the states not recognizing the holiday.[17]

In 1992, the group was one of the first rap acts to perform at the Reading Festival in the UK, headlining the second day of the three-day festival.[18]

1994–2019: Later years and member changes

After a 1994 motorcycle accident shattered his left leg and kept him in the hospital for a full month,[citation needed] Terminator X relocated to his 15-acre farm in Vance County, North Carolina.[citation needed] By 1998, he was ready to retire from the group and focus full-time on raising African black ostriches on his farm.[19] In late 1998, the group started looking for Terminator X's permanent replacement. Following several months of searching for a DJ, Professor Griff saw DJ Lord at a Vestax Battle and approached him about becoming the DJ for Public Enemy.[20] DJ Lord joined as the group's full-time DJ just in time for Public Enemy's 40th World Tour.[21] Since 1999, he has been the official DJ for Public Enemy on albums and world tours while winning numerous turntablist competitions, including multiple DMC finals.[22]

In 2007, the group released an album entitled How You Sell Soul to a Soulless People Who Sold Their Soul?.[citation needed] Public Enemy's single from the album was "Harder Than You Think".[citation needed] Four years after How You Sell Soul ... , in January 2011, Public Enemy released the album Beats and Places, a compilation of remixes and "lost" tracks.[citation needed] On July 13, 2012, Most of My Heroes Still Don't Appear on No Stamp was released and was exclusively available on iTunes.[citation needed] In July 2012, on UK television an advert for the London 2012 Summer Paralympics featured a short remix of the song "Harder Than You Think". The advert caused the song to reach No. 4[23] in the UK Singles Chart on September 2, 2012.[24] On July 30, 2012, Public Enemy performed a free concert with Salt-N-Pepa and Kid 'n Play at Wingate Park in Brooklyn, New York as part of the Martin Luther King Jr. Concert Series.[citation needed] On August 26, 2012, Public Enemy performed at South West Four music festival in Clapham Common in London.[citation needed] On October 1, 2012 The Evil Empire of Everything was released.[citation needed] On June 29, 2013, they performed at Glastonbury Festival 2013.[citation needed] On September 14, 2013, they performed at Riot Fest & Carnival 2013 in Chicago, Illinois.[citation needed] On September 20, 2013, they performed at Riot Fest & Side Show in Byers, Colorado.[citation needed]

In 2014, Chuck D launched PE 2.0 with Oakland rapper Jahi as a spiritual successor and "next generation"[25] of Public Enemy.[26] Jahi met Chuck D backstage during a soundcheck at the 1999 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and later appeared as a support act on Public Enemy's 20th Anniversary Tour in 2007.[citation needed] PE 2.0's task is twofold, Jahi says, to "take select songs from the PE catalog and cover or revisit them" as well as new material with members of the original Public Enemy including DJ Lord, Davy DMX, Professor Griff and Chuck D.[27] PE 2.0's first album People Get Ready was released on October 7, 2014. InsPirEd PE 2.0's second album and part two of a proposed trilogy was released a year later on October 11, 2015.[26] Man Plans God Laughs, Public Enemy's thirteenth album, was released in July 2015.[citation needed] On June 29, 2017, Public Enemy released their fourteenth album, Nothing Is Quick in the Desert.[citation needed] The album was available for free download through Bandcamp until July 4, 2017.[28]

2020–present: Controversy, Public Enemy Radio, and return to Def Jam

In late February 2020, it was announced that Public Enemy (billed as Public Enemy Radio) would perform at a campaign rally in Los Angeles on March 1, 2020, for Bernie Sanders, who was campaigning to be the nominee of the Democratic Party in the 2020 presidential election.[29] Days following the announcement, Flavor Flav's lawyer Matthew Friedman issued a cease-and desist letter asking the campaign to not use the group's name or logo, stating: "While Chuck is certainly free to express his political views as he sees fit — his voice alone does not speak for Public Enemy".[30] Chuck D responded to the statement by saying: "Flavor chooses to dance for his money and not do benevolent work like this. He has a year to get his act together and get himself straight or he's out".[30] A lawyer for Chuck D added: "Chuck could perform as Public Enemy if he ever wanted to; he is the sole owner of the Public Enemy trademark. He originally drew the logo himself in the mid-80s, is also the creative visionary and the group's primary songwriter, having written Flavor's most memorable lines".[30][31]

On March 1, 2020, prior to the group's performance at the Sanders rally, Chuck D, DJ Lord, Jahi, James Bomb and Pop Diesel issued a joint statement announcing that Flavor Flav had been fired from the group, stating: "Public Enemy and Public Enemy Radio will be moving forward without Flavor Flav. We thank him for his years of service and wish him well".[32] The statement also claimed: "Flavor Flav has been on suspension since 2016 when he was MIA from the Harry Belafonte benefit in Atlanta, Georgia. That was the last straw for the group. He had previously missed numerous live gigs from Glastonbury to Canada, album recording sessions and photo shoots. He always chose to party over work".[33] On March 2, 2020, it was announced that Public Enemy Radio would be releasing the album Loud Is Not Enough which was due for release in April 2020. The album was to feature the lineup of Chuck D, DJ Lord, Jahi and the S1Ws and according to a statement from the group it will be "taking it back to hip hop’s original DJ-and-turntablist foundation".[34]

On April 1, 2020, it was revealed Flavor Flav's firing was a publicity stunt to gain attention and provide a commentary on disinformation, with Reuters claiming that Chuck D and Flavor Flav "concocted a fake split to grab attention and highlight media bias towards reporting bad news about hip hop".[5] In an interview with rapper Talib Kweli, Chuck D stated that the stunt was inspired by Orson Welles' 1938 radio drama "The War of the Worlds".[35] In response, Flavor Flav tweeted: "I am not a part of your hoax" and: "There are more serious things in the world right now than April Fool's jokes and dropping records. The world needs better than this,,,you say we are leaders so act like one".[36]

On June 19, 2020, Public Enemy (with Flavor Flav), released the single and music video for their anti-Donald Trump song, "State of the Union (STFU)".[citation needed] Chuck D stated, "Our collective voices keep getting louder. The rest of the planet is on our side. But it's not enough to talk about change. You have to show up and demand change. Folks gotta vote like their lives depend on it, cause it does".[37] In 2020, the group returned to Def Jam and released their thirteenth studio album, What You Gonna Do When the Grid Goes Down?, on September 25, 2020.[38]

Legacy

Public Enemy made contributions to the hip-hop world with sonic experimentation as well as political and cultural consciousness, which infused itself into skilled and poetic rhymes. Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote that "PE brought in elements of free jazz, hard funk, even musique concrète, via [its] producing team the Bomb Squad, creating a dense, ferocious sound unlike anything that came before."[39][40] Public Enemy held a strong, pro-black, political stance. Before PE, politically motivated hip-hop was defined by a few tracks by Ice-T, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Kurtis Blow and Boogie Down Productions. Other politically motivated opinions were shared by prototypical artists Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets. PE was a revolutionary hip-hop act whose entire image rested on a specified political stance. With the successes of Public Enemy, many hip-hop artists began to celebrate Afrocentric themes, such as Kool Moe Dee, Gang Starr, X Clan, Eric B. & Rakim, Queen Latifah, the Jungle Brothers, and A Tribe Called Quest.

Public Enemy was one of the first hip-hop groups to do well internationally. PE changed the Internet's music distribution capability by being one of the first groups to release MP3-only albums,[41] a format virtually unknown at the time.

Public Enemy helped to create and define "rap metal" by collaborating with Living Colour in 1988 ("Funny Vibe"), with Sonic Youth on the 1990 song "Kool Thing", and with New York thrash metal outfit Anthrax in 1991. The single "Bring the Noise" was a mix of semi-militant black power lyrics, grinding guitars, and sporadic humor. The two bands, cemented by a mutual respect and the personal friendship between Chuck D and Anthrax's Scott Ian, introduced a hitherto alien genre to rock fans, and the two seemingly disparate groups toured together. Flavor Flav's pronouncement on stage that "They said this tour would never happen" (as heard on Anthrax's Live: The Island Years CD) has become a legendary comment in both rock and hip-hop circles. Metal guitarist Vernon Reid (of Living Colour) contributed to Public Enemy's recordings, and PE sampled Slayer's "Angel of Death" half-time riff on "She Watch Channel Zero?!"

Members of the Bomb Squad produced or remixed works for other acts, like Bell Biv DeVoe, Ice Cube, Vanessa Williams, Sinéad O'Connor, Blue Magic, Peter Gabriel, L.L. Cool J, Paula Abdul, Jasmine Guy, Jody Watley, Eric B & Rakim, Third Bass, Big Daddy Kane, EPMD, and Chaka Khan. According to Chuck D, "We had tight dealings with MCA Records and were talking about taking three guys that were left over from New Edition and coming up with an album for them. The three happened to be Ricky Bell, Michael Bivins, and Ronnie DeVoe, later to become Bell Biv DeVoe. Ralph Tresvant had been slated to do a solo album for years, Bobby Brown had left New Edition and experienced some solo success beginning in 1988, and Johnny Gill had just been recruited to come in, but [he] had come off a solo career and could always go back to that. At MCA, Hiram Hicks, who was their manager, and Louil Silas, who was running the show, were like, 'Yo, these kids were left out in the cold. Can y'all come up with something for them?' It was a task that Hank, Keith, Eric, and I took on to try to put some kind of hip-hop-flavored R&B shit down for them. Subsequently, what happened in the four weeks of December [1989] was that the Bomb Squad knocked out a large piece of the production and arrangement on Bell Biv DeVoe's three-million selling album Poison. In January [1990], they knocked out Fear of a Black Planet in four weeks, and PE knocked out Ice Cube's album AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted in four to five weeks in February."[42] They have also produced local talent such as Son of Bazerk, Young Black Teenagers, Leaders of the New School, Kings of Pressure, and True Mathematics—and gave producer Kip Collins his start in the business.

Poet and hip-hop artist Saul Williams uses a sample from Public Enemy's "Welcome to the Terrordome" in his song "Tr[n]igger" on the Niggy Tardust album. He also used a line from the song in his poem, amethyst rocks.

The Manic Street Preachers track "Repeat (Stars And Stripes)" is a remix of the band's own anti-monarchy tirade by Public Enemy production team The Bomb Squad of whom James Dean Bradfield and Richey Edwards were big fans. The song samples "Countdown to Armageddon" from It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. The band had previously sampled Public Enemy on their 1991 single Motown Junk.

The revolutionary influence of the band is seen throughout hip-hop and is recognized in society and politics. The band "rewrote the rules of hip-hop", changing the image, sound and message forever.[43][44] Pro-black lyrics brought political and social themes to hardcore hip hop, with stirring ideas of racial equality, and retribution against police brutality, aimed at disenfranchised blacks, but appealing to all the poor and underrepresented.[45][46] Before Public Enemy, hip hop music was seen as "throwaway entertainment", with trite sexist and homophobic lyrics.[47] Public Enemy brought social relevance and strength to hip hop. They also brought black activist Louis Farrakhan to greater popularity, and they gave impetus to the Million Man March in 1995.[48]

The influence of the band goes also beyond hip-hop in a unique[citation needed] way, indeed the group was cited as an influence by artists as diverse as Autechre (selected in the All Tomorrow's Parties in 2003), Nirvana (It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back being cited by Kurt Cobain among his favorite albums), Moby (also selected It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back as one of his favourite albums),[49] Nine Inch Nails (mentioned the band in Pretty Hate Machine credits), Björk (included Rebel Without a Pause in her The Breezeblock Mix in July 2007), Tricky (did a cover of Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos and appears in Do You Wanna Go Our Way ??? video), The Prodigy (included Public Enemy No. 1 in The Dirtchamber Sessions Volume One), Ben Harper, Underground Resistance (cited by both Mad Mike and Jeff Mills), Orlando Voorn, M.I.A., Amon Tobin, Mathew Jonson, Aphex Twin (Welcome To The Terrordome being the first track played after the introduction at the Coachella Festival in April 2008), Rage Against the Machine (sampling the track in their song "Renegades of Funk"), Porcupine Tree's Fear of a Blank Planet, and My Bloody Valentine who was influenced by the Bomb Squad's production for their sound.[50]

Controversy

Anti-Semitism

In 1989, in an interview with Public Enemy for the Washington Times, the interviewing journalist, David Mills, lifted some quotations from a UK magazine in which the band were asked their opinion on the Arab–Israeli conflict. Professor Griff commented that "Jews are responsible for the majority of the wickedness in the world" (p. 177), a quote from The International Jew. Shortly after, Chuck D expressed an apology on his behalf.[51] At a June 21, 1989, press conference, Chuck D announced Griff's dismissal from the group,[51] and a June 28 statement by Russell Simmons, president of Def Jam Recordings and Rush Artists Management, stated that Chuck D. had disbanded Public Enemy "for an indefinite period of time".[52] By August 10, however, Chuck D denied that he had disbanded the group, and stated that Griff had been re-hired as "Supreme Allied Chief of Community Relations" (in contrast to his previous position with the group as Minister of Information).[51] Griff later denied holding anti-Semitic views and apologized for the remarks.[53] Several people who had worked with Public Enemy expressed concern about Chuck D's leadership abilities and role as a social spokesman.[54]

In his 2009 book, entitled Analytixz,[55] Griff criticized his 1989 statement: "to say the Jews are responsible for the majority of wickedness that went on around the globe I would have to know about the majority of wickedness that went on around the globe, which is impossible ... I'm not the best knower. Then, not only knowing that, I would have to know who is at the crux of all of the problems in the world and then blame Jewish people, which is not correct." Griff also said that not only were his words taken out of context, but that the recording has never been released to the public for an unbiased listen.

The controversy and apologies on behalf of Griff spurred Chuck D to reference the negative press they were receiving. In 1990, Public Enemy issued the single "Welcome to the Terrordome", which contains the lyrics: "Crucifixion ain't no fiction / So-called chosen frozen / Apologies made to whoever pleases / Still they got me like Jesus". These lyrics have been cited by some in the media as anti-Semitic, making supposed references to the concept of the "chosen people" with the lyric "so-called chosen" and Jewish deicide with the last line.[56]

In 1999 the group released an album entitled There's a Poison Goin' On. The title of the last song on the album is called "Swindler's Lust". The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) claimed that the title of the song was a word play on the title of the Steven Spielberg movie Schindler's List about the genocide of Jews in World War II.[57] Similarly in 2000 a Public Enemy spin off group under the name Confrontation Camp, a name according to the ADL, that is a pun on the term concentration camp, released an album.[58] The group consisted of Kyle Jason, Chuck D (under the name Mistachuck) and Professor Griff.

Homophobia

Fear of a Black Planet's "Meet the G That Killed Me" described propagation of HIV. Upon its 1990 release, New York Times writer Peter Watrous criticized the song's lyrics as containing "stupidly crude" homophobia.[59] Zoe Williams defended Public Enemy against charges of homophobia, citing the same passage as Watrous:

If you look at the seminal black artists at the start of hip-hop, Public Enemy and Niggaz Wit Attitudes, you won't actually find much homophobia. The only recorded homophobic lyric in Public Enemy's canon was: 'Man to man/ I don't know if they can/ From what I know/ The parts don't fit' (a lyric from "Meet the G that Killed Me" on Fear of a Black Planet").

— Williams, Zoe, "Hiphopophobia", The Guardian, 29 April 2003

Group members

Current members

- Chuck D (Carlton D. Ridenhour) – MC

- Flavor Flav (William J. Drayton, Jr.) – Hype man, multi-instrumentalist

- Sammy Sam (Samule Kim) – MC, Music Producer

- Khari Wynn – lead guitars, music director, MD, AMD

- DJ Lord (Lord Aswod) – DJ

- Davy DMX (David Franklin Reeves Jr.) – bass

- T-Bone Motta – drums, percussion

- S1W

- Brother James (James Norman)

- Brother Roger (Roger Chillous)

- Brother Mike (Michael Williams)

- James Bomb (James Allen)

- The Interrogator (Shawn K. Carter)

- Big Casper (Tracy D. Walker)

- Pop Diesel (sometimes spelt Popp Diezel)

Former members

- Terminator X (Norman Rogers) – DJ, Producer

- Professor Griff (Richard Griffin) – Minister of Information

- DJ Johnny "Juice" Rosado – DJ, Scratching, Turntablist, Producer

- Sister Souljah (Lisa Williamson) – Minister of Information (took over Richard Griffin's place when Griffin left group)

- Brian Hardgroove – bass, guitars

- Michael Faulkner – drums, percussion

- S1W

- Jacob "Big Jake" Shankle

- The Bomb Squad

- Hank Shocklee (James Hank Boxley III) *original member

- Keith Shocklee (Keith Boxley) *original member

- Eric "Vietnam" Sadler *original member

- Gary G-Wiz (Gary Rinaldo) (took Eric Sadler's place when Sadler left group)

Discography

Studio albums

- Yo! Bum Rush the Show (1987)

- It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988)

- Fear of a Black Planet (1990)

- Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black (1991)

- Muse Sick-n-Hour Mess Age (1994)

- There's a Poison Goin' On (1999)

- Revolverlution (2002)

- New Whirl Odor (2005)

- How You Sell Soul to a Soulless People Who Sold Their Soul? (2007)

- Most of My Heroes Still Don't Appear on No Stamp (2012)

- The Evil Empire of Everything (2012)

- Man Plans God Laughs (2015)

- Nothing Is Quick in the Desert (2017)

- Loud Is Not Enough (2020) (released under the name Public Enemy Radio)

- What You Gonna Do When the Grid Goes Down? (2020)

Collaboration albums

- Rebirth of a Nation with Paris (2006)

Soundtrack albums

- He Got Game (1998)

Awards and nominations

Grammy Awards

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | "Fight the Power" | Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| 1991 | Fear of a Black Planet | Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| 1992 | Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black | Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| 1993 | Greatest Misses | Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group | Nominated |

| 1995 | "Bring the Noise" (with Anthrax) | Best Metal Performance | Nominated |

American Music Awards

| Year | Nominated work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back | Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album | Nominated |

| 1991 | Fear of a Black Planet | Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album | Nominated |

| 1992 | Apocalypse 91... The Enemy Strikes Black | Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album | Nominated |

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Public Enemy was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Pinn, Anthony (2005). "Rap Music and Its Message". In Forbes, Bruce; Mahan, Jeffrey H. (eds.). Religion and Popular Culture in America. University of California Press. p. 262. ISBN 9780520932579. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Flavor of the month". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy is 'moving forward without Flavor Flav' after Bernie Sanders rally dispute". USA Today. Retrieved March 6, 2020.

- ^ a b McCombs, Joseph (December 11, 2012). "Decking the Hall: The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's New Members – Public Enemy". Time. New York. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ a b "Public Enemy split with Flavor Flav was a hoax, group now says". Reuters. April 1, 2020.

- ^ "On April Fools' Day, Public Enemy reveals Flavor Flav's firing was a hoax". Los Angeles Times. April 1, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (July 5, 1998). "Is Anyone Out There Really Listening?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Public Enemy - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ "Public Enemy, Rush, Heart, Donna Summer to be inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". EW.com. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Chang 2005, pp. 239, 241-242.

- ^ Chuck D. and Yusuf Jah, Fight the Power, p. 82.

- ^ Chang 2005, p. 247.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon. "Public Enemy", Melody Maker, October 17, 1987.

- ^ SPIN - Google Books. September 1989. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Canadian Music - HuffPost Canada". music.aol.ca. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Spike. "Riot on the Set: How Public Enemy Crafted the Anthem 'Fight the Power'". rollingstone.com, June 30, 2014. Retrieved May 28, 2017

- ^ "Public Enemy Look Back at 20 Years of 'By the Time I Get to Arizona'". Spin Magazine. SpinMedia. November 10, 2011.

- ^ Azerrad, Michael (October 29, 1992). "Nirvana, Public Enemy, Beastie Boys Cross the Pond for Reading Fest". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 25, 2021.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "My Ostrich Weighs a Ton". Vibe. March 1998.

- ^ "Dj Lord of the battle". In the Mix. June 4, 2002.

- ^ "DMC Kicks Back ... Mr. Lord-Public Enemy Spinner & Hip Hop King". DMC World Magazine. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Dj Lord Biography". Rap Artists. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "PUBLIC ENEMY | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". Officialcharts.com. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "UK Top 40 Singles Chart = Radio 1". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "SUN 5.31 The Next Gen of Public Enemy PE 2.0 DOORS: 9:15 PM / SHOW: 9:30 PM". Yoshis.com. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Arnold, Eric K. (October 8, 2014). "The Oak Q & A: Jahi as PE2.0". Oakculture.wordpress.com. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ "The time is now. - The time is now. - BIO". October 26, 2015. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Public Enemy Release Surprise New Album 'Nothing Is Quick in the Desert'". Rolling Stone. June 29, 2017.

- ^ Moore, Sam (February 27, 2020). "Public Enemy to perform at Bernie Sanders rally". NME. NME. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Flavor Flav Sends Bernie Sanders Cease and Desist Over Public Enemy Rally Gig". Yahoo. March 1, 2020.

- ^ "Chuck D Responds to Bernie Sanders Endorsement Controversy: 'I Don't Attack Flav On What He Don't Know'". Billboard. March 1, 2020.

- ^ "Public Enemy Fire Flavor Flav After Bernie Sanders Rally Spat". Rolling Stone. March 1, 2020.

- ^ Aniftos, Rania (March 2, 2020). "Public Enemy Releases Statement on Flavor Flav Exit, Says He's Been on 'Suspension Since 2016'". Billboard. Billboard. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ "Public Enemy and Public Enemy Radio to Move Forward Without Flavor Flav". Spin. March 2, 2020.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (April 1, 2020). "Public Enemy's Chuck D says feud with Flavor Flav was a hoax: "We takin' April Fools"". NME. NME. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ "Chuck D says Flavor Flav firing was a stunt, but Flav disagrees". CNN. April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Public Enemy Takes on Trump In Scorching New Single "State Of The Union (STFU)": Stream". Consequence of Sound. June 19, 2020.

- ^ Eustice, Kyle (August 28, 2020). "Public Enemy Returns To Def Jam Armed With New Album 'What You Gonna Do When The Grid Goes Down?'". HipHopDX. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Stephen Thomas Erlewine. "It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back - Public Enemy | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Electric & Acoustic Guitar Gear, Lessons, News, Blogs, Video, Tabs & Chords". GuitarPlayer.com. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ "Transcriptions Topics: Artists of Information: Public Enemy and MP3". May 9, 2003. Archived from the original on May 9, 2003. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Fight The Power, pp. 236–237

- ^ "Public Enemy - Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Public Enemy Talks 'It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back' on Its 30th Anniversary". Billboard. June 30, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Boissoneault, Lorraine. "The Ballad of the Boombox: What Public Enemy Tells Us About Hip-Hop, Race and Society". Smithsonian. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Jihad Hassan Muhammad. "The Undying Influence of Public Enemy". The Dallas Weekly. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Pettie, Andrew (December 9, 2011). "Public Enemy: Prophets of Rage - how the hip hop group rescued rap". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Russell Simmons Says "Public Enemy Changed Everything About Black America"". HipHopDX.com. September 17, 2014. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "The Quietus | Features | Baker's Dozen | Corrupting Sonic DNA: Moby's Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "CLASSIC TRACKS: My Bloody Valentine 'Only Shallow'". Soundonsound.com. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Pareles, Jon (August 11, 1989). "Public Enemy Rap Group Reorganizes After Anti-Semitic Comments". The New York Times. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ^ Pareles, John (June 29, 1989). "Rap Group Disbands Under Fire". The New York Times. p. C19.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (April 10, 1990). "POP MUSIC REVIEW: Public Enemy Keeps Up Attack". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (February 4, 1990). "Rap—The Power and the Controversy: Success has validated pop's most volatile form, but its future impact could be shaped by the continuing Public Enemy uproar". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Professor Griff. Analytixz: 20 Years of Conversations and Enter-views with Public Enemy's Minister of Information. Atlanta: RATHSI Publishing, 2009, p. 12.

- ^ Christgau, Robert. Jesus, Jews, and the Jackass Theory: Public Enemy

- ^ "Profits of Rage". Villagevoice.com. July 13, 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ Archive-Chris-Nelson. "Jewish Group Decries Public Enemy's 'Swindler's Lust'". MTV News. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Public Enemy Makes Waves - and Compelling Music". The New York Times. April 22, 1990. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "ROCK ON THE NET ... your music resource and more - music charts, info pages, live tv and new release info, music news links and more". Rockonthenet.com. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

Bibliography

- Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York: Picador. ISBN 0312425791.

- Chuck D: Lyrics of a Rap Revolutionary, Off Da Books, 2007 ISBN 0-9749484-1-1

- Chuck D with Yusuf Jah, Fight the Power, Delacorte Press, 1997 ISBN 0-385-31868-5

- Fuck You Heroes, Glen E. Friedman Photographs 1976–1991, Burning Flags Press, 1994, ISBN 0-9641916-0-1

- Serpick, Evan. "Public Enemy Look Back at 20 Years of 'By the Time I Get to Arizona'." Spin. Spin, November 10, 2011. Web.

- White, Miles. Race, Rap and the performance of Mascinity in American Popular Culture. 2011. University of Illinois. Urbana. ISBN 978-0-252-07832-3

External links

- Public Enemy discography at Discogs

- Videos

- Public Enemy (band)

- African-American musical groups

- American hip hop groups

- Musical groups established in 1985

- Def Jam Recordings artists

- East Coast hip hop groups

- Political music groups

- LGBT-related controversies in music

- Obscenity controversies in music

- Hardcore hip hop groups

- 1985 establishments in New York (state)

- Musical groups from Long Island

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners