Frances Wisebart Jacobs

Frances Wisebart Jacobs | |

|---|---|

Frances Wisebart Jacobs, ca. 1890 | |

| Born | Frances Wisebart March 29, 1843 |

| Died | November 3, 1892 (aged 49) |

| Occupation(s) | School teacher, philanthropist |

| Known for | Founding the United Way |

| Spouse |

Abraham Jacobs (m. 1863) |

Frances Jacobs (née Wisebart; March 29, 1843 – November 3, 1892) was born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, to Jewish[1] Bavarian immigrants and raised in Cincinnati, Ohio. She married Abraham Jacobs, the partner of her brother Jacob, and came west with him to Colorado where Wisebart and Jacobs had established businesses in Denver and Central City. In Denver, Frances Jacobs became a driving force for the city's charitable organizations and activities, with national exposure. Among the philanthropical organizations she founded, she is best remembered as a founder of the United Way and the Denver's Jewish Hospital Association.

Biography

Frances Wisebart was born March 29, 1843, in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, to Leon Wisebart, a tailor, and his wife.[2] In addition to Frances, they had a son, Jacob (also called Benjamin), and five more girls, all of whom attended public school.[2][3] Frances was a school teacher in Cincinnati, Ohio before she married Abraham Jacobs[3] on February 18, 1863.[2] After their marriage, the newlywed couple traveled by wagon to Colorado where Abraham Jacobs and Frances' brother, Jacob Wisebart had established stores in Denver and Central City. Frances and Abraham had two sons, one named Benjamin, and a daughter, named Evelyn.[2][3]

The Jacobs were beset a number of difficulties during their marriage: major fires to two stores, the OK Clothing Store in Denver went out of business in 1885 and the early death of one of their sons. The April 19, 1863 "great fire" of Denver was one of the fires.[4] Frances' brother, Jacob was the fifth mayor of Central City. The store he ran with his brother-in-law Abraham Jacobs, called the Wisebart store, succumbed to fire after the Denver 1863 fire, with $50,000 in damages.[3] In 1866 Frances' sister, Mollie, married Philip Trounstine in Cincinnati, Ohio. They moved to Denver where Trounstine became a volunteer firefighter in March 1866, the first leader of Denver's firefighters and managed Abraham Jacob's Denver clothing store.[5]

Following the Central City fire Frances and Abraham moved to Denver for a fresh start.[2] Abraham Jacobs established and ran the OK Clothing Store,[6] served on the Denver city council, helped draft the Denver "people's constitution", was involved in the important merger of Denver and Auraria, and established and ran a stagecoach line until 1869, when it became unprofitable.[3][7]

Frances Wisebart Jacobs, involved in Denver charitable activities shortly after settling in Denver,[6] was described as a "frail woman with an unfailing sense of humor."[8] She became a forceful, persuasive speaker engaging and inspiring support for Denver's charitable organizations.[6] Jacob's niece said of her, "Aunt Frank was that rare combination of dreamer and doer. She not only dreamed of free kindergartens and orphanages, a home for the aged and a hospital, but with good business sense brought them to reality."[2]

Frances Wisebart Jacobs was quoted in the Rocky Mountain News, August 27, 1888, as having said: "I know that whenever women lead in good work, men will follow."[9]

Background

In 1858 settlers arrived to frontier land: "The early pioneer came to a silent wilderness. He took hold of the territory 'in the raw.' He had nothing by his hands, his energy and his courage to start a new civilization in the wilderness."[10] In 1859 and 1860 people began arriving in the thousands to settle in the mountains, mining camps or valleys.[11]

People also came to Colorado was the restorative benefits of its "clean air and sunshine."[8][12] Starting in the 1860s, when tuberculosis (TB) was a worldwide problem, physicians in the eastern United States recommended that their patients go to Colorado.[8] As a result, the number of people with tuberculosis, called "lungers", in the state grew alarmingly[8] and without the services or facilities to support their needs.[6][13] Not knowing how to manage a population of homeless ill people, many were taken to jail.[13] Because of the number of people with TB flocking to Denver, by the 1880s it was nicknamed the "World's Sanitarium".[9] Cynthia Stout, a history scholar, asserted that by 1900 "one-third of Colorado's population were residents of the state because of tuberculosis."[14]

-

Denver Colorado in 1859

-

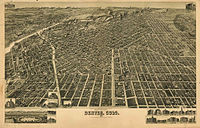

Denver, Colorado 22 years later, in 1881

-

Denver, Colorado in 1889

Charitable activities

Jacobs was known across the nation as the "Mother of Charities" for her ground-breaking philanthropic service in Denver, Colorado.[15][16]

Hebrew Ladies' Benevolent Society

To meet the needs of Jewish pioneers living in Denver,[17] in 1872 Jacobs organized, and was president of, the Hebrew Ladies' Benevolent Society.[12][15] At that time, there were 300 Jewish pioneers in Denver,[17] from Germany, Lithuania, Belorussia, Ukraine and Russian Poland. They came to Colorado to cure their tuberculosis or to pursue opportunities and freedom that previously had been denied to them.[18]

Jacobs was troubled by the number of critically ill people with tuberculosis she saw on the streets and who lived like refugees in tents and shacks. As a member and early president of the Hebrew Ladies' Benevolent Society, Jacobs cared for critically ill Jewish people living in squalor along the Platte River banks and West Colfax by bringing soup, coal, clothing, soap and physicians.[6][19] She also aided those who, due to hemorrhaging, fell ill on the street.[2][19] West Colfax, comparable to New York City's Lower East Side, was a community primarily of Eastern European Jews.[20]

The nonprofit, nonsectarian organization is known today as Jewish Family Service of Colorado, serves 21,500 people per year.[17]

Denver Ladies' Relief Society

To help serve the entire Denver community, she helped found the nonsectarian Denver Ladies' Relief Society in 1874[6] and served as president. A capable and compelling speaker, Jacobs increased public awareness of unfair workplace conditions for women, the need for separate quarters for women in prisons, staffed by women, and the adversity of homeless women.[8]

Free kindergarten

Jacobs visited the free Golden Gate kindergarten when she attended and spoke at the San Francisco National Conference of Charities and Correction. Golden Gate became a model for Denver's first free kindergarten at the Stanley Public School established by the Free Kindergarten Association that Jacobs founded in 1885.[8][9] It was Frances's belief that "God never made a pauper in the world, children come into the world and conditions and surroundings make them either princes or paupers."[19]

Charitable Organization Society, later the United Way

In 1887, she joined Father William O'Brien, Reverend Myron Reed, Dean H. Martin Hart and another Catholic priest to create the Charity Organization Society, coordinating fundraising and other efforts and sharing the proceeds with a federation of twenty-three charities. Jacobs served as secretary for the remainder of her life.[6]

The Charity Organization Society, the first of its kind in the nation, evolved in 1922 to the national Community Chest and ultimately to the United Way.[6]

Denver's Jewish Hospital Association

Jacobs wrote of the Denver residents reaction to people with tuberculosis, "Most of the community ignores those who roam the city coughing or hemorrhaging."[13] In 1883 she organized a hospital benefit and over several years insisted that the Denver community face the reality of the lack of respectful treatment services and facilities.[8] According to one Denver journalist, "Everyone put down his pencil to hear her tell of the crucial need for a hospital".[12]

Due to the advocacy by Rabbi William S. Friedman of Denver's Temple Emanuel, Denver's Jewish Hospital Association was organized in November 1889,[8] incorporated in April 1890 and a hospital cornerstone was laid in October of that year.[12][13]

The Denver's Jewish Hospital Association trustees voted to name the hospital for Jacobs the year after her death;[21] Construction was completed in 1893, but the unfurnished Frances Jacobs Hospital stood empty for six years due to lack of funds as the result of an economic downturn. B'nai B'rith, a Jewish charitable organization, accepted the hospital as one of its endeavors and the hospital opened its doors as National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives in Denver on December 10, 1899.[12] The hospital was the first in the world to accept only destitute TB patients, from anywhere in the country, under the condition that upon leaving the hospital "they did not become a charge upon the Denver community."[21]

Due in part to the research of the National Jewish Medical and Research Center, tuberculosis is no longer an epidemic.[12]

Death and memorial

Jacobs, ill herself, delivered medicine to a sick child on a rainy night in 1892. She contracted pneumonia and was hospitalized at Marquette Sanitorium in Denver and died on November 3, 1892, following the illness that lasted for three months.[21]

Over 4,000 people attended her funeral at the Temple Emanuel which was open to people of all faiths, classes, and races. A week later, a memorial service was held at the First Congregational Church. Speakers included prominent Denver people, such as the city's mayor, and the governor of Colorado. J.S. Appel, her coworker said "For long years she gave her time and her services to the practical work of charity, and looked more poor and wretched people in the face than any other person in Denver. The keynote of her character was… her great fund of humor that made her see the bright side of everything, that enabled her to devote her life to the work of saving and uplifting humanity… This love of humor was the safety valve that kept her heart from bursting at the sorrows and miseries she beheld."[21]

Jacobs is memorialized as one of 16 Colorado pioneers, and the only woman, in a stained glass window at the Colorado state capitol Rotunda. She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1987.[22] In 1994, Jacobs was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame,[23] and in 2000 Jacobs and the National Jewish Medical and Research Center were awarded the Denver Mayor's Millennium Award.[24]

A bronze statue sits in the lobby of the National Jewish Medical and Research Center, a memorial to Jacobs, with her holding a bag of medicines and soaps.[25]

See also

- Dr. Frederick J. Bancroft, 19th century Colorado public health advocate

- Dr. Josepha Williams Douglas, one of the state's first female doctors and owner and operator of a Denver sanitarium

Notes

- ^ "Frances Wisebart Jacobs: Denver's Jewish Pioneer "Mother of Charities" – JMAW – Jewish Museum of the American West". Archived from the original on 2017-11-10. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g Frances Wisebart Jacobs, The Colorado Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d e Varnell, 38.

- ^ Varnell, 38-39.

- ^ Abrams, 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Varnell, 39.

- ^ Abrams, 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Varnell, 40.

- ^ a b c A Legacy of Caring, Center for Judaic Studies.

- ^ Hill, 157.

- ^ Hill, 156.

- ^ a b c d e f Denver Jewry Builds a Hospital, American Jewish Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d Davis, 23.

- ^ Tuberculosis in Colorado history, The Denver Post.

- ^ a b National Women's Hall of Fame.

- ^ Abrams, 13.

- ^ a b c Jewish Family Services, History.

- ^ Abrams, 7-8, 71.

- ^ a b c Davis, 22.

- ^ Abrams, 8.

- ^ a b c d Varnell, 41.

- ^ "Colorado Women's Hall of Fame, Frances Wisebart Jacobs". Archived from the original on 2019-07-19. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- ^ Varnell, 42.

- ^ Mayor announced Millennium Award honorees, Denver Business Journal.

- ^ Abrams, 75.

References

- "A Legacy of Caring: Jewish Women in Early Colorado: Frances Wisebart Jacobs – Mother of All Charities". Center for Judaic Studies, University of Denver. 2007. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- Abrams (2007). Jewish Denver 1859-1940. Charleston and more: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-4829-6.

- American Jewish Historical Society (2011). "Denver Jewry Builds a Hospital". The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise.

- Davis, Richard (2010). The Intangibles of Leadership. Mississauga, Ontario: John Wiley & Sons. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-470-67915-9.

- "Frances Wisebart Jacobs" (PDF). The Colorado Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- "Frances Wisebart Jacobs". National Women's Hall of Fame. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- Hill, A. (1915). Colorado Pioneers in Picture and Story. Denver: Brock-Hafner Press. p. 156.

- "Jewish Family Service, History". Jewish Family Service of Colorado. 2008–2011. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- "Mayor announced Millennium Award honorees". Denver Business Journal, of American City Business Journals, Inc. December 4, 2000. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- Perry, Marilyn Elizabeth (2000). Jacobs, Frances Wisebart (1843-1892), welfare worker and charity organizer | American National Biography. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1501041.

- "Tuberculosis in Colorado history". The Denver Post. 2007-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- Varnell, Jeanne (1999). Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Boulder: Johnson Press. ISBN 1-55566-214-5.

Further reading

- Ida Libert Uchill (2000). Pioneers, Peddlers & Tsadikim: The story of Jews in Colorado 3rd ed. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-0870815935.