Mount Sanford (Alaska)

| Mount Sanford | |

|---|---|

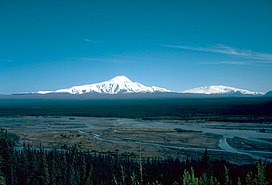

Mount Sanford (left) and Mount Wrangell in 1980 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 16,237 ft (4,949 m)[1] NAVD88 |

| Prominence | 7,687 ft (2,343 m)[1] |

| Isolation | 40.3 mi (64.8 km)[1] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 62°12′50″N 144°07′44″W / 62.2138889°N 144.1288889°W[2] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska, U.S. |

| Parent range | Wrangell Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS Gulkana A-1 |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Shield volcano[3] |

| Last eruption | 320,000 years ago |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | July 21, 1938 by Terris Moore and Bradford Washburn[4] |

| Easiest route | Sheep Glacier (North Ramp) Route, Alaska Grade 2[4] |

Mount Sanford is a shield volcano[3] in the Wrangell Volcanic Field, in eastern Alaska near the Copper River. It is the sixth highest mountain in the United States and the third highest volcano behind Mount Bona and Mount Blackburn. The south face of the volcano, at the head of the Sanford Glacier, rises 8,000 feet (2,400 m) in 1 mile (1,600 m) resulting in one of the steepest gradients in North America.

Geology

Mount Sanford is mainly composed of andesite, and is an ancient peak, being mostly Pleistocene, although some of the upper parts of the mountain may be Holocene. The mountain first began developing 900,000 years ago, when it began growing on top of three smaller shield volcanoes that had coalesced. Although obscured by icefields, the uppermost 2,000 feet (610 m) of the mountain appear to be a lava dome filling a larger summit crater.[5]

Two notable events in the mountain's history include a large rhyolite flow which traveled some 11 miles (18 km) to the north east of the peak and has a volume of about 5 cubic miles (21 km3), and another flow which erupted from a rift zone on the flank of the volcano some 320,000 years ago. The second flow was basaltic in nature and marks the most recent activity of the volcano. The flow was dated using radiometric methods.[3]

Observers have reported minor activity at Sanford, primarily vapor clouds or plumes from ice and rockfalls. Some reported incidents may have been orographic clouds, while others have been interpreted as avalanches.[6]

The majority of Mount Sanford above 8,000 feet (2,400 m) is covered by icefields, merging to the south with that surrounding Mount Wrangell. The largest glacier on Sanford is the Sanford Glacier, whose source lies at the steep cirque that cuts into the south side of the mountain.[5]

History

The mountain was named in 1885 by Lieutenant Henry T. Allen of the U.S. Army, a descendant of Reuben Sanford.[2]

Mount Sanford was first climbed on July 21, 1938 by noted mountaineers Terris Moore and Bradford Washburn, via the still standard North Ramp route up the Sheep Glacier. This route "offers little technical difficulty" and "is a glacier hike all the way to the summit"[4] but is still a serious mountaineering challenge (Alaska Grade 2) due to the altitude and latitude of the peak. The base of the route is usually accessed by air, but landing near the mountain is not straightforward.

On March 12, 1948, Northwest Airlines Flight 4422 crashed into Mount Sanford. All 24 passengers and 6 crew members were killed. The wreckage was quickly covered by snow and was not found again until 1999.[7]

The first solo ascent of Sanford was achieved on September 19, 1968, by Japanese mountaineer Naomi Uemura, who later died just after making the first solo winter ascent of Denali.[8]

See also

- List of mountain peaks of North America

- List of the highest major summits of the United States

- List of the most prominent summits of the United States

- List of the most isolated major summits of the United States

- List of volcanoes in the United States

References

- ^ a b c "Mount Sanford, Alaska". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- ^ a b "Mount Sanford". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ a b c "Sanford". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ a b c Wood, Michael; Coombs, Colby (2001). Alaska: A climbing guide. The Mountaineers. pp. 146–148. ISBN 0-89886-724-X.

- ^ a b Richter, Donald H.; Rosenkrans, Danny S.; Steigerwald, Margaret J. "Guide to the Volcanoes of the Western Wrangll Mountains, Alaska, U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2072" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey.

- ^ "Sanford reported activity". Alaska Volcano Observatory. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ Vickery, Jim Dale (1998). Winter Sign. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-8166-2969-2.

Sources

- Richter, Donald H.; Rosenkrans, Danny S.; Steigerwald, Margaret J. (1995). Guide to the Volcanoes of the Western Wrangell Mountains, Alaska (PDF). USGS Bulletin 2072.

- Richter, Donald H.; Preller, Cindi C.; Labay, Keith A.; Shew, Nora B. (2006). Geologic Map of the Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska. USGS Scientific Investigations Map 2877.

- Winkler, Gary R. (2000). A Geologic Guide to Wrangell—Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska: A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes. USGS Professional Paper 1616. ISBN 0-607-92676-7.

- Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen, eds. (1990). Volcanoes of North America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

External links

- Mount Sanford at the Alaska Volcano Observatory

- "Sanford Trip Report". Mt. Sanford Expedition via the Sheep Glacier, 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- Shield volcanoes of the United States

- Mountains of Alaska

- Volcanoes of Alaska

- Landforms of Valdez–Cordova Census Area, Alaska

- Wrangell–St. Elias National Park and Preserve

- Pleistocene volcanoes

- Pleistocene North America

- Quaternary United States

- North American 4000 m summits

- Mountains of Unorganized Borough, Alaska

- Volcanoes of Unorganized Borough, Alaska

- Polygenetic shield volcanoes