American Museum of Natural History

Looking at the east entrance from Central Park West | |

| |

| Established | April 6, 1869[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | 200 Central Park West, New York, NY 10024 United States |

| Type | Natural history |

| Visitors | 5 million (2018)[2] |

| President | Ellen V. Futter |

| Public transit access | New York City Bus: M7, M10, M11, M79 New York City Subway: |

| Website | AMNH.org |

American Museum of Natural History | |

| Built | 1874 |

| NRHP reference No. | 76001235[3] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 24, 1976 |

| Designated NYCL | August 24, 1967 |

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH), located on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York City, is one of the largest[clarification needed][citation needed] natural history museums in the world. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 interconnected buildings housing 45 permanent exhibition halls, in addition to a planetarium and a library. The museum collections contain over 34 million specimens[4] of plants, animals, fossils, minerals, rocks, meteorites, human remains, and human cultural artifacts as well as specialized collections for frozen tissue and genomic and astrophysical data, of which only a small fraction can be displayed at any given time, and occupies more than 2 million square feet (190,000 m2). The museum has a full-time scientific staff of 225, sponsors over 120 special field expeditions each year,[5] and averages about five million visits annually.[6]

The one mission statement of the American Museum of Natural History is: "To discover, interpret, and disseminate—through scientific research and education—knowledge about human cultures, the natural world, and the universe."[7]

History

Founding

Before construction of the present complex, the museum was housed in the Arsenal building in Central Park. Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., the father of Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th U.S. President, was one of the founders along with John David Wolfe, William T. Blodgett, Robert L. Stuart, Andrew H. Green, Robert Colgate, Morris K. Jesup, Benjamin H. Field, D. Jackson Steward, Richard M. Blatchford, J. P. Morgan, Adrian Iselin, Moses H. Grinnell, Benjamin B. Sherman, A. G. Phelps Dodge, William A. Haines, Charles A. Dana, Joseph H. Choate, Henry G. Stebbins, Henry Parish, and Howard Potter. The founding of the museum realized the dream of naturalist Dr. Albert S. Bickmore. Bickmore, a one-time student of zoologist Louis Agassiz, lobbied tirelessly for years for the establishment of a natural history museum in New York. His proposal, backed by his powerful sponsors, won the support of the Governor of New York, John Thompson Hoffman, who signed a bill officially creating the American Museum of Natural History on April 6, 1869.[8]

Construction

In 1874, the cornerstone was laid for the museum's first building, which is now hidden from view by the many buildings in the complex that today occupy most of Manhattan Square. The original Victorian Gothic building, which was opened in 1877,[1] was designed by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould, both already closely identified with the architecture of Central Park.[9]: 19–20

Expansion

The original building was soon eclipsed by the south range of the museum, designed by J. Cleaveland Cady, an exercise in rusticated brownstone neo-Romanesque, influenced by H. H. Richardson.[10] It extends 700 feet (210 m) along West 77th Street,[11] with corner towers 150 feet (46 m) tall. Its pink brownstone and granite, similar to that found at Grindstone Island in the St. Lawrence River, came from quarries at Picton Island, New York.[12]

The entrance on Central Park West, the New York State Memorial to Theodore Roosevelt, completed by John Russell Pope in 1936, is an overscaled Beaux-Arts monument.[13] It leads to a vast Roman basilica, where visitors are greeted with a cast of a skeleton of a rearing Barosaurus defending her young from an Allosaurus. The museum is also accessible through its 77th Street foyer, renamed the "Grand Gallery" and featuring a fully suspended Haida canoe. The hall leads into the oldest extant exhibit in the museum, the hall of Northwest Coast Indians.[14]

Later additions, restorations, and renovations

Since 1930, little has been added to the exterior of the original building. The architect Kevin Roche and his firm Roche-Dinkeloo have been responsible for the master planning of the museum since the 1990s.[15] Various renovations to both the interior and exterior have been carried out. Renovations to the Dinosaur Hall were undertaken starting in 1991,[15] and the museum also restored the mural in Roosevelt Memorial Hall in 2010.[16] In 1992 the Roche-Dinkeloo firm designed the eight-story AMNH Library.[citation needed] However, the entirety of the master plan was ultimately not fully realized, and by 2015, the museum consisted of 25 separate buildings that were poorly connected.[17]

The museum's south façade, spanning 77th Street from Central Park West to Columbus Avenue was cleaned, repaired and re-emerged in 2009. Steven Reichl, a spokesman for the museum, said that work would include restoring 650 black-cherry window frames and stone repairs. The museum's consultant on the latest renovation is Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., an architectural and engineering firm with headquarters in Northbrook, Illinois.[10]

In 2014, the museum published plans for a $325 million, 195,000-square-foot (18,100 m2) annex, the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, on the Columbus Avenue side.[18] Designed by Studio Gang, Higgins Quasebarth & Partners and landscape architects Reed Hilderbrand, the new building's pink Milford granite facade will have a textural, curvilinear design inspired by natural topographical elements showcased in the museum, including "geological strata, glacier-gouged caves, curving canyons, and blocks of glacial ice," as a striking contrast to the museum's predominance of High Victorian Gothic, Richardson Romanesque and Beaux Arts architectural styles. The interior itself would contain a new entrance from Columbus Avenue north of 79th Street; a multiple-story storage structure containing specimens and objects; rooms to display these objects; an insect hall; an "interpretive" "wayfinding wall", and a theater.[17][19] This expansion was originally supposed to be located to the south of the existing museum, occupying parts of Theodore Roosevelt Park. The expansion was relocated to the west side of the existing museum, and its footprint was reduced in size, due to opposition to construction in the park. The annex would instead replace three existing buildings along Columbus Avenue's east side, with more than 30 connections to the existing museum, and it would be six stories high, the same height as the existing buildings. The plans for the expansion were scrutinized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[17] On October 11, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously approved the expansion. Construction of the Gilder Center, which was expected to break ground the next year following design development and Environmental Impact Statement stages, would entail demolition of three museum buildings built between 1874 and 1935.[19] The museum formally filed plans to construct the expansion in August 2017,[20] but due to community opposition, construction did not start until June 2019. The project is expected to be complete by 2022.[21][22]

Presidents

The museum's first two presidents were John David Wolfe (1870–1872) and Robert L. Stuart (1872–1881), both among the museum's founders. The museum was not put on a sound footing until the appointment of the third president, Morris K. Jesup (also one of the original founders), in 1881. Jesup was president for over 25 years, overseeing its expansion and much of its golden age of exploration and collection. The fourth president, Henry Fairfield Osborn, was appointed in 1906 on the death of Jesup. Osborn consolidated the museum's expansion, developing it into one of the world's foremost natural history museums. F. Trubee Davison was president from 1933 to 1951, with A. Perry Osborn as Acting President from 1941 to 1946. Alexander M. White was president from 1951 to 1968. Gardner D. Stout was president from 1968 to 1975. Robert Guestier Goelet from 1975 to 1988. George D. Langdon, Jr. from 1988 to 1993. Ellen V. Futter has been president of the museum since 1993.[23]

Presidents of the American Museum of Natural History

- John David Wolfe (1869-1872);

- Robert L. Stuart (1872-1881);

- Morris K. Jesup (1881-1908);

- Henry Fairfield Osborn (1908-1933);

- F. Trubee Davison (1933-1935);

- Roy Chapman Andrews (1935-1951);

- A. Perry Osborn (1941-1946, Ad interim);

- Alexander M. White (1951-1968);

- Gardner D. Stout (1968-1975);

- Robert G. Goelet (1975-1988);

- George D. Langdon Jr. (1988-1993);

- Ellen V. Futter (1993–present).

Associated names

Famous names associated with the museum include the paleontologist and geologist Henry Fairfield Osborn; the dinosaur-hunter of the Gobi Desert, Roy Chapman Andrews (one of the inspirations for Indiana Jones);[9]: 97–8 photographer Yvette Borup Andrews; George Gaylord Simpson; biologist Ernst Mayr; pioneer cultural anthropologists Franz Boas and Margaret Mead; explorer and geographer Alexander H. Rice, Jr.; and ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy. J. P. Morgan was also among the famous benefactors of the museum.

Mammal halls

Old World mammals

Akeley Hall of African Mammals

Named after taxidermist Carl Akeley, the Akeley Hall of African Mammals is a two-story hall located directly behind the Theodore Roosevelt rotunda. Its 28 dioramas depict in meticulous detail the great range of ecosystems found in Africa and the mammals endemic to them. The centerpiece of the hall is a pack of eight African elephants in a characteristic 'alarmed' formation.[24] Though the mammals are typically the main feature in the dioramas, birds and flora of the regions are occasionally featured as well. In the 80 years since Akeley Hall’s creation, many of the species within have become endangered, some critically, and the locations deforested.[25] Despite this, none of the species are yet extinct, in part thanks to the work of Carl Akeley himself (see Virunga National Park). The hall connects to the Hall of African Peoples.

History

The Hall of African Mammals was first proposed to the museum by Carl Akeley around 1909.[26] His original concept contained forty dioramas which would present the rapidly vanishing landscapes and animals of Africa. The intent was that a visitor of the hall, “may have the illusion, at worst, of passing a series of pictures of primeval Africa, and at best, may think for a moment that he has stepped 5,000 miles (8,000 km) across the sea into Africa itself.” Akeley’s proposal was a hit with both the board of trustees and then museum president, Henry Fairfield Osborne. To fund its creation, Daniel Pomeroy, a trustee of the museum and partner at J.P. Morgan, offered interested investors the opportunity to accompany the museum’s expeditions in Africa in exchange for funding.[26]

Akeley began collecting specimens for the hall as early as 1909, famously encountering Theodore Roosevelt in the midst of the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African expedition (two of the elephants featured in the museum’s center piece were donated by Roosevelt, a cow, shot by Roosevelt himself, and a calf, shot by his son Kermit).[27] On these early expeditions, Akeley would be accompanied by his former apprentice in taxidermy, James L. Clark, and artist, William R. Leigh.[26]

When Akeley returned to Africa to collect gorillas for the hall’s first diorama, Clark remained behind and began scouring the country for artists to create the backgrounds. The eventual appearance of the first habitat groups would have a huge impact on the museum. Akeley and Clark’s skillful taxidermy paired with the backgrounds painted under Leigh’s direction created an illusion of life in these animals that made the museum’s other exhibits seem dull in comparison (the museum’s original style of exhibition can still be seen in the small area devoted to birds and animals of New York). Plans for other diorama halls quickly emerged and by 1929 Birds of the World, the Hall of North American Mammals, the Vernay Hall of Southeast Asian Mammals, and the Hall of Oceanic Life were all in stages of planning or construction.[26]

After Akeley’s unexpected death during the Eastman-Pommeroy expedition in 1926, responsibility of the hall’s completion fell to James L. Clark. Despite being hampered by the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, Clark’s passion for Africa and his dedication to his former mentor kept the project alive. In 1933, Clark would hire architectural artist James Perry Wilson to assist Leigh in the painting of backgrounds. More technically minded than Leigh, Wilson would make many improvements on Leigh’s techniques, including a range of methods to minimize the distortion caused by the dioramas’ curved walls.[26]

In 1936, William Durant Campbell, a wealthy board member with a desire to see Africa, offered to fund several dioramas if allowed to obtain the specimens himself. Clark agreed to this arrangement and shortly after Campbell left to collect the okapi and black rhinoceros specimens accompanied by artist Robert Kane. Campbell would be involved, in one capacity or another, with several other subsequent expeditions. Despite setbacks including malaria, flooding, foreign government interference, and even a boat sinking, these expeditions would succeed in acquiring some of Akeley Hall’s most impressive specimens.[26][28] Back in the museum, Kane would join Leigh and Wilson, along with a handful of other artists in completing the hall’s remaining dioramas. Though construction of the hall was completed in 1936, the dioramas would gradually open between the mid-1920s and early 1940s.[29]

Hall of Asian Mammals

The Hall of Asian Mammals, sometimes referred to as the Vernay-Faunthorpe Hall of Asian Mammals, is a one-story hall located directly to the left of the Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda. It contains 8 complete dioramas, 4 partial dioramas, and 6 habitat groups of mammals and locations from India, Nepal, Burma, and Malaysia. The hall opened in 1930 and, similar to Akeley Hall, is centered around 2 Asian elephants. At one point, a giant panda and Siberian tiger were also part of the Hall's collection, originally intended to be part of an adjoining Hall of North Asian Mammals (planned in the current location of Stout Hall of Asian Peoples). These specimens can currently be seen in the Hall of Biodiversity.[24][31]

History

Specimens for the Hall of Asian Mammals were collected over six expeditions led by Arthur S. Vernay and Col. John Faunthorpe (as noted by stylized plaques at both entrances). The expeditions were funded entirely by Vernay, a wealthy, British-born, New York antiques dealer. He characterized the expense as a British tribute to American involvement in World War I.[32]

The first Vernay-Faunthorpe expedition took place in 1922. At the time, many of the animals Vernay was seeking, such as the Sumatran rhinoceros and Asiatic lion, were already rare and facing the possibility of extinction. To acquire these specimens, Vernay would have to make many appeals to regional authorities in order to obtain hunting permits.[33] The relations he would forge during this time would assist later museum related expeditions headed by Vernay in gaining access to areas previously restricted to foreign visitors.[34] Artist Clarence C. Rosenkranz accompanied the Vernay-Faunthorpe expeditions as field artist and would later paint the majority of the diorama backgrounds in the hall.[35] These expeditions were also well documented in both photo and video, with enough footage of the first expedition to create a feature-length film, Hunting Tigers in India (1929).[36]

| Species and Locations Represented in the Hall of Asian Mammals | ||

|---|---|---|

| India (Assam) | Hoolock gibbon | |

| - | Thamin | |

| (Awadh) | Sambar | Barasingha |

| - | Chital | |

| (Bhopal) | Sambar | Dhole (listed as wild dog) |

| (Bikanir) | Blackbuck | Chinkara |

| (Biligiriranga Hills, listed as Kallegal Range) | Leopard | |

| (Mysore) | Gaur | Indian roller |

| (Manas River) | Wild water buffalo | |

| Nepal (Base of the Himalayas) | Tiger | |

| (Morang) | Indian rhinoceros | |

| Burma (Rangoon) | Banteng | |

| Habitat groups | ||

| Sloth bear | ||

| Four-horned antelope | Smooth-coated otter | |

| Muntjac | Spotted chevrotain | |

| Sumatran rhinoceros | ||

| Hog deer | Indian wild boar | |

| Asiatic lion |

New World mammals

Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals

The Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals features 43 dioramas of various mammals of the American continent, north of tropical Mexico. Each diorama places focus on a particular species, ranging from the largest megafauna to the smaller rodents and carnivorans. Notable dioramas include the Alaskan brown bears looking at a salmon after they scared off an otter, a pair of wolves, a pair of Sonoran jaguars, and dueling bull Alaska moose.

History

The Hall of North American Mammals opened in 1942 with only ten dioramas, including those of the larger North American mammals. In 1948, the wolf diorama was installed, but further progress on the hall was halted as World War II broke out. After the war the hall ceased completion in 1954. Since that time, the hall had remained much the same and the majority of the mounts were weathering and bleaching. A massive restoration project began in late 2011 due to a large donation from Jill and Lewis Bernard. Taxidermists were brought in to clean the mounts and skins and artists restored the diorama backdrops. In October 2012 the hall was reopened as the Bernard Hall of North American Mammals and included scientifically-updated signage for each diorama.

Hall of Small Mammals

The Hall of Small Mammals is an offshoot of the Bernard Family Hall of North American Mammals. There are several small dioramas featuring small mammals found throughout North America, including collared peccaries, Abert's squirrel, and a wolverine.

Birds, reptiles, and amphibian halls

Sanford Hall of North American Birds

The Sanford Hall of North American birds is a one-story hall located on the third floor of the museum, above the Hall of African Peoples and between the Hall of Primates and Akeley Hall’s second level. Its 25 dioramas depict birds from across North America in their native habitats. Opening in 1909, the dioramas in Sanford Hall were the first to be exhibited in the museum and are, at present, the oldest still on display. At the far end of the hall are two large murals by ornithologist and artist, Louis Agassiz Fuertes. In addition to the species listed below, the hall also has display cases devoted to large collections of warblers, owls, and raptors.

History

Conceived by museum ornithologist Frank Chapman, construction began on dioramas for the Hall of North American Birds as early as 1902. The Hall is named for Chapman's friend and amateur ornithologist Leonard C. Sanford, who partially funded the hall and also donated the entirety of his own bird specimen collection to the museum.[37]

Although Chapman was not the first to create museum dioramas, he was responsible for many of the innovations that would separate and eventually define the dioramas in the American Museum. Whereas other dioramas of the time period typically featured generic scenery, Chapman was the first to bring artists into the field with him in the hopes of capturing a specific location at a specific time. In contrast to the dramatic scenes later created by Carl Akeley for the African Hall, Chapman wanted his dioramas to evoke a scientific realism, ultimately serving as a historical record of habitats and species facing a high probability of extinction.[37]

At the time of Sanford Hall's construction, plume-hunting for the millinery trade had brought many coastal bird species to the brink of extinction, most notably the great egret. Frank Chapman was a key figure in the conservation movement that emerged during this time. His dioramas were created with the intention of furthering this conservationist cause, giving museum visitors a brief glimpse at the dwindling bird species being lost in the name of fashion. Thanks in part to Chapman's efforts, both inside and outside of the museum, conservation of these bird species would be very successful, establishing refuges, such as Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge, and eventually leading to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.[38]

Hall of Birds of the World

The global diversity of bird species is exhibited in this hall. 12 dioramas showcase various ecosystems around the world and provide a sample of the varieties of birds that live there. Example dioramas include South Georgia featuring king penguins and skuas, the East African plains featuring secretarybirds and bustards, and the Australian outback featuring honeyeaters, cockatoos, and kookaburras.

Whitney Memorial Hall of Oceanic Birds

This particular hall has undergone a complicated history over the years since its founding in 1953. Frank Chapman and Leonard C. Sanford, originally museum volunteers, had gone forward with creation of a hall to feature birds of the Pacific islands. In the years up to its founding, the museum had engaged in various expeditions to Fiji, New Zealand, and the Marianas (among other locations) to collect birds for the exhibit. The hall was designed as a completely immersive collection of dioramas, including a circular display featuring birds-of-paradise. In 1998, The Butterfly Conservatory was installed inside the hall originally as a temporary exhibit, but as the popular demand of the exhibit increased, the Hall of Oceanic Birds has more or less remained closed by the museum.

Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians

The Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians serves as an introduction to herpetology, with many exhibits detailing reptile evolution, anatomy, diversity, reproduction, and behavior. Notable exhibits include a Komodo dragon group, an American alligator, Lonesome George, the last Pinta island tortoise, and poison dart frogs.

In 1926, W. Douglas Burden, F.J. Defosse, and Emmett Reid Dunn collected specimens of the Komodo Dragon for the museum. Burden's chapter "The Komodo Dragon", in Look to the Wilderness, describes the expedition, the habitat, and the behavior of the dragon.[39]

Biodiversity and environmental halls

Hall of North American Forests

The Hall of North American Forests is a one-story hall located on the museum’s ground floor in between the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall and the Warburg Hall of New York State Environments. It contains ten dioramas depicting a range of forest types from across North America as well as several displays on forest conservation and tree health. Constructed under the guidance of noted botanist Henry K. Svenson (who also oversaw Warburg Hall’s creation) and opened in 1959, each diorama specifically lists both the location and exact time of year depicted.[40] Trees and plants featured in the dioramas are constructed of a combination of art supplies and actual bark and other specimens collected in the field. The entrance to the hall features a cross section from a 1,400-year-old sequoia taken from the King's River grove on the west flank of the Sierra Mountains in 1891.[41]

| Locations Represented in the Hall of North American Forests | |

|---|---|

| Oak-Hickory Forest in late August | Ozark Plateau |

| Northern Spruce-Fir in mid-August | Lake Nipigon |

| Jeffrey Pine Forest in early June | Inyo National Forest |

| Olympic Rain Forest in mid-June | Quinault Rainforest |

| Timberline of the Northern Rocky Mountains in mid-July | Logan Pass |

| Pinyon-Juniper Woodland in early October | Colorado National Monument |

| Giant Cactus Forest in mid-April | Saguaro National Park |

| Southeastern Coastal Plain Forest in mid-March | Coosawhatchie River, South Carolina |

| Mixed Deciduous Forest in late April | Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

| Early October in Southern New Hampshire | Lake Sunapee |

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments

Warburg Hall of New York State Environments is a one-story hall located on the museum’s ground floor in between the Hall of North American Forests and the Grand Hall. Based on the town of Pine Plains and near-by Stissing Mountain in Dutchess County,[42] the hall gives a multi-faceted presentation of the eco-systems typical of New York. Aspects covered include soil types, seasonal changes, and the impact of both humans and nonhuman animals on the environment. It is named for the German-American philanthropist, Felix M. Warburg. Originally known as the "Hall of Man and Nature", Warburg Hall opened in 1951.[42] It has changed little since and is now frequently regarded for its retro-modern styling.[43] The hall shares many of the exhibit types featured throughout the museum as well as one display type, unique to Warburg, which features a recessed miniature diorama behind a foreground of species and specimens from the environment depicted.

Milstein Hall of Ocean Life

The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life focuses on marine biology, botany and marine conservation. The hall is most famous for its 94-foot (29 m)-long[44] blue whale model, suspended from the ceiling behind its dorsal fin.

The upper level of the hall exhibits the vast array of ecosystems present in the ocean. Dioramas compare and contrast the life in these different settings including polar seas, kelp forests, mangroves, coral reefs and the bathypelagic. It attempts to show how vast and varied the oceans are while encouraging common themes throughout. The lower, and arguably more famous, half of the hall consists of several large dioramas of larger marine organisms. It is on this level that the famous "Squid and the Whale" diorama sits, depicting a hypothetical fight between the two creatures.[45] Other notable exhibits in this hall include the Andros Coral Reef Diorama, which is the only two-level diorama in the Western Hemisphere.[46] One of the most famous icons of the museum is a life-sized fiberglass model of a 94 foot (29 m) long Atlantic blue whale. The whale was redesigned dramatically in the 2003 renovation: its flukes and fins were readjusted, a navel was added, and it was repainted from a dull gray to various rich shades of blue. Upper dioramas are smaller versions of the ecosystems when the bottom versions are much bigger and more life like.

History

In 1910, museum president Henry F. Osborn proposed the construction of a large building in the museum's southeast courtyard to house a new Hall of Ocean Life in which "models and skeletons of whales" would be exhibited. This proposal to build in the courtyard marked a major reappraisal of the museum's original architectural plan. Calvert Vaux had designed the museum complex to include four open courtyards in order to maximize the amount of natural light entering the surrounding buildings. In 1969, a renovation gave the hall a more explicit focus on oceanic megafauna in order to paint the ocean as a grandiose and exciting place. The key component of the renovation became the addition of a lifelike blue whale model to replace a popular steel and papier-mâché whale model that had hung in the Biology of Mammals hall. Richard Van Gelder oversaw the creation of the hall in its current incarnation.[47]

The hall was renovated once again in 2003, this time with environmentalism and conservation being the main focal points. Paul Milstein was a real estate developer, business leader and philanthropist and Irma Milstein is a long-time Board member of the American Museum of Natural History. The 2003 renovation included refurbishment of the famous blue whale, suspended high above the 19,000 square foot (1,750 m2) exhibit floor, and updating of the 1930s and 1960s dioramas. New displays were linked to schools via technology.[48]

Human origins and cultural halls

Cultural halls

Stout Hall of Asian Peoples

The Stout Hall of Asian Peoples is a one-story hall located on the museum’s second floor in between the Hall of Asian Mammals and Birds of the World. It is named for Gardner D. Stout, a former president of the museum, and was primarily organized by Dr. Walter A. Fairservis, a longtime museum archaeologist. Opened in 1980, Stout Hall is the museum’s largest anthropological hall and contains artifacts acquired by the museum between 1869 and the mid-1970s.[49] Many famous expeditions sponsored by the museum are associated with the artifacts in the hall, including the Roy Chapman Andrews expeditions in Central Asia and the Vernay-Hopwood Chindwin expedition.[50]

Stout Hall has two sections: Ancient Eurasia, a small section devoted to the evolution of human civilization in Eurasia, and Traditional Asia, a much larger section containing cultural artifacts from across the Asian continent. The latter section is organized to geographically correspond with two major trade routes of the Silk Road. Like many of the museum’s exhibition halls, the artifacts in Stout Hall are presented in a variety of ways including exhibits, miniature dioramas, and 5 full scale dioramas. Notable exhibits in the Ancient Eurasian section include reproductions from the archaeological sites of Teshik-Tash and Çatalhöyük, as well as a full size replica of a Hammurabi Stele. The Traditional Asia section contains areas devoted to major Asian countries, such as Japan, China, Tibet, and India, while also including a vast array of smaller Asian tribes including the Ainu, Semai, and Yakut.[51]

-

A forced perspective, miniature diorama of Isfahan

-

A Yakut shaman performs a healing rite in this diorama

-

A range of costumes worn by women in Islamic Asia

Hall of African Peoples

The Hall of African Peoples is located behind Akeley Hall of African Mammals and underneath Sanford Hall of North American Birds. It is organized by the four major ecosystems found in Africa: River Valley, Grasslands, Forest-Woodland, and Desert.[52] Each section presents artifacts and exhibits of the peoples native to the ecosystems throughout Africa. The hall contains three dioramas and notable exhibits include a large collection of spiritual costumes on display in the Forest-Woodland section. Uniting the sections of the hall is a multi-faceted comparison of African societies based on hunting and gathering, cultivation, and animal domestication. Each type of society is presented in a historical, political, spiritual, and ecological context. A small section of African diaspora spread by the slave trade is also included. Below is a brief list of some of the tribes and civilizations featured:

River Valley: Ancient Egyptians, Nubians, Kuba, Lozi

Grasslands: Pokot, Shilluk, Barawa

Forest-Woodland: Yoruba, Kofyar, Mbuti

Hall of Mexico and Central America

The Hall of Mexico and Central America is a one-story hall located on the museum’s second floor behind Birds of the World and before the Hall of South American Peoples. It presents archaeological artifacts from a broad range of pre-Columbian civilizations that once existed across Middle America, including the Maya, Olmec, Zapotec, and Aztec. Because most of these civilizations did not leave behind recorded writing or have any contact with Western civilization, the overarching aim of the hall is to piece together what it is possible to know about them from the artifacts alone.

The museum has displayed pre-Columbian artifacts since its opening, only a short time after the discovery of the civilizations by archaeologists, with its first hall dedicated to the subject opening in 1899.[53] As the museum’s collection grew, the hall underwent major renovations in 1944 and again in 1970 when it re-opened in its current form.[54][55] Notable artifacts on display include the Kunz Axe and a full-scale replica of Tomb 104 from the Monte Albán archaeological site, originally displayed at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2017) |

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2015) |

The hall opened in 1971, named the Hall of Pacific Peoples, and reopened as the Margaret Mead Hall of Pacific Peoples in 1984.

Indians halls

Hall of Northwest Coast Indians

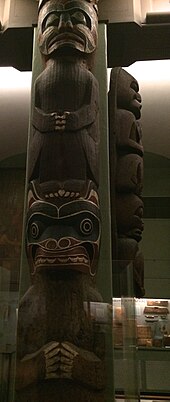

The Hall of Northwest Coast Indians is a one-story hall located on the museum's ground floor behind the Grand Gallery and in between Warburg and Spitzer Halls. Opened in 1900 under the name "Jesup North Pacific Hall", it is currently the oldest exhibition hall in the museum, though it has undergone many renovations in its history. The hall contains artifacts and exhibits of the tribes of the North Pacific Coast cultural region (Southern Alaska, Northern Washington, and a portion of British Columbia). Featured prominently in the hall are four "House Posts" from the Kwakwaka'wakw nation and murals by William S. Taylor depicting native life.[56]

History

Artifacts in the hall originated from three main sources. The earliest of these was a gift of Haida artifacts (including the now famous Haida canoe of the Grand Gallery) collected by John Wesley Powell and donated by Herbert Bishop in 1882. This was followed by the museum’s purchase of two collections of Tlingit artifacts collected by Lt. George T. Emmons in 1888 and 1894.[57]

The remainder of the hall’s artifacts were collected during the famed Jesup North Pacific Expedition between 1897 and 1902. Led by influential anthropologist Franz Boas and financed by museum president Morris Ketchum Jesup, the expedition was the first for the museum’s Division of Anthropology and is now considered the, “foremost expedition in American anthropology”.[58] Many famous ethnologists took part, including George Hunt, who secured the Kwakwaka’wakw House Posts that currently stand in the hall.[59]

At the time of its opening, the Hall of Northwest Coast Indians was one of four halls dedicated to the native peoples of United States and Canada. It was originally organized in two sections, the first being a general area pertaining to all peoples of the region and the second a specialized area divided by tribe. This was a point of contention for Boas who wanted all artifacts in the hall to be associated with the proper tribe (much like it is currently organized), eventually leading to the dissolution of Boas’ relationship with the museum.[57][60]

Other tribes featured in the hall include: Coastal Salish, Nuu-chah-nulth (listed as Nootka), Tsimshian, and Nuxalk (listed as Bella Coola)

Hall of Plains Indians

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2016) |

The primary focus of this hall is the North American Great Plains peoples as they were at the middle of the 19th Century, including depictions of Blackfeet (see also: Blackfoot Confederacy), Hidatsa, and Dakota cultures. Of particular interest is a Folsom point discovered in 1926 New Mexico, providing valuable evidence of early American colonization of the Americas.

Hall of Eastern Woodlands Indians

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2016) |

This hall details the lives and technology of traditional Native American peoples in the woodland environments of eastern North America. Particular cultures exhibited include Cree, Mohegan, Ojibwe, and Iroquois.

Human origins halls

Bernard and Anne Spitzer Hall of Human Origins

The Bernard and Anne Spitzer Hall of Human Origins, formerly The Hall of Human Biology and Evolution, opened on February 10, 2007.[61] Originally known under the name "Hall of the Age of Man", at the time of its original opening in 1921 it was the only major exhibition in the United States to present an in-depth investigation of human evolution.[62] The displays traced the story of Homo sapiens, illuminated the path of human evolution and examined the origins of human creativity.

Many of the celebrated displays from the original hall can still be viewed in the present expanded format. These include life-size dioramas of our human predecessors Australopithecus afarensis, Homo ergaster, Neanderthal, and Cro-Magnon, showing each species demonstrating the behaviors and capabilities that scientists believe they were capable of. Also displayed are full-sized casts of important fossils, including the 3.2-million-year-old Lucy skeleton and the 1.7-million-year-old Turkana Boy, and Homo erectus specimens including a cast of Peking Man.

The hall also features replicas of ice age art found in the Dordogne region of southwestern France. The limestone carvings of horses were made nearly 26,000 years ago and are considered to represent some of the earliest artistic expression of humans.[63]

Earth and planetary science halls

Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites

The Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites contains some of the finest specimens in the world including Ahnighito, a section of the 200 ton Cape York meteorite which was found at the location of the same name in Greenland. The meteorite's great weight—at 34 tons, it is the largest meteorite on display at any museum in the world[64]—requires support by columns that extend through the floor and into the bedrock below the museum.[65]

The hall also contains extra-solar nanodiamonds (diamonds with dimensions on the nanometer level) more than 5 billion years old. These were extracted from a meteorite sample through chemical means, and they are so small that a quadrillion of these fit into a volume smaller than a cubic centimeter.[66]

Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Gems and Minerals

The Harry Frank Guggenheim Hall of Minerals houses hundreds of unusual geological specimens. It adjoins the Morgan Memorial Hall of Gems showcasing many rare, and valuable gemstones. The exhibit was designed by the architectural firm of Wm. F. Pedersen and Assoc. with Fred Bookhardt in charge. Vincent Manson was the curator of the Mineralogy Department. The exhibit took six years to design and build, 1970–1976. The New York Times architectural critic, Paul Goldberger, said, "It is one of the finest museum installations that New York City or any city has seen in many years".[67]

On display are many renowned samples that are chosen from among the museum's more than 100,000 pieces. Included among these are the Patricia Emerald, a 632 carat (126 g), 12 sided stone. It was discovered during the 1920s in a mine high in the Colombian Andes and was named for the mine-owner's daughter. The Patricia is one of the few large gem-quality emeralds that remains uncut.[68] Also on display is the 563 carat (113 g) Star of India, the largest, and most famous, star sapphire in the world. It was discovered over 300 years ago in Sri Lanka,[citation needed] most likely in the sands of ancient river beds from where star sapphires continue to be found today. It was donated to the museum by the financier J.P. Morgan. The thin, radiant, six pointed star, or asterism, is created by incoming light that reflects from needle-like crystals of the mineral rutile which are found within the sapphire. The Star of India is polished into the shape of a cabochon, or dome, to enhance the star's beauty.[69] Among other notable specimens on display are a 596-pound (270 kg) topaz, a 4.5 ton specimen of blue azurite/malachite ore that was found in the Copper Queen Mine in Bisbee, Arizona at the start of the 20th century;[70] and a rare, 100 carat (20 g) orange-colored padparadschan sapphire from Sri Lanka, considered "the mother of all pads."[71] The collection also includes the Midnight Star, a 116.75-carat deep purplish-red star ruby, which was from Sri Lanka and was also donated by J.P. Morgan to the AMNH, like the Star of India. It was also donated to AMNH the same year the Star of India was donated to the AMNH, 1901.

On October 29, 1964, the Star of India, along with the Midnight Star, the DeLong Star Ruby, and the Eagle Diamond were all stolen from the museum.[72] The burglars, Jack Roland "Murph The Surf" Murphy, and his two accomplices, Allen Dale Kuhn and Roger Frederick Clark, gained entrance by climbing through a bathroom window they had unlocked hours before the museum was closed. The Midnight Star and the DeLong Star Ruby were later recovered in Miami. A few weeks later, also in Miami, the Star of India was recovered from a locker in a bus station, but the Eagle Diamond was never found; it may have been recut or lost.[73] Murphy, Kuhn, and Clark were all caught later on and were all sentenced to three years in jail, and they all were granted parole.[citation needed]

-

Assorted faceted and polished minerals

-

Labradorite specimen

-

Microcline specimen

-

Quartz var. amethyst geode

David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth

The David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Hall of Planet Earth is a permanent hall devoted to the history of Earth, from accretion to the origin of life and contemporary human impacts on the planet. Several sections also discuss the studies of Earth systems, including geology, glaciology, atmospheric sciences, and volcanology.

The exhibit is famous for its large, touchable rock specimens. The hall features striking samples of banded iron and deformed conglomerate rocks, as well as granites, sandstones, lavas, and three black smokers.

The north section of the hall, which deals primarily with plate tectonics, is arranged to mimic the Earth's structure, with the core and mantle at the center and crustal features on the perimeter.

Fossil halls

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Most of the museum's collections of mammalian and dinosaur fossils remain hidden from public view. They are kept in numerous storage areas located deep within the museum complex. Among these, the most significant storage facility is the ten story Childs Frick Building which stands within an inner courtyard of the museum. During construction of the Frick, giant cranes were employed to lift steel beams directly from the street, over the roof, and into the courtyard, in order to ensure that the classic museum façade remained undisturbed. The predicted great weight of the fossil bones led designers to add special steel reinforcement to the building's framework, as it now houses the largest collection of fossil mammals and dinosaurs in the world. These collections occupy the basement and lower seven floors of the Frick Building, while the top three floors contain laboratories and offices. It is inside this particular building that many of the museum's intensive research programs into vertebrate paleontology are carried out.

Other areas of the museum contain repositories of life from the past. The Whale Bone Storage Room is a cavernous space in which powerful winches come down from the ceiling to move the giant fossil bones about. The museum attic upstairs includes even more storage facilities, such as the Elephant Room, while the tusk vault and boar vault are downstairs from the attic.[9]: 119–20

The great fossil collections that are open to public view occupy the entire fourth floor of the museum as well as a separate exhibit that is on permanent display in the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall, the museum's main entrance. The fourth floor exhibits allow the visitor to trace the evolution of vertebrates by following a circuitous path that leads through several museum buildings. On the 77th street side of the museum the visitor begins in the Orientation Center and follows a carefully marked path, which takes the visitor along an evolutionary tree of life. As the tree "branches" the visitor is presented with the familial relationships among vertebrates. This evolutionary pathway is known as a cladogram.

To create a cladogram, scientists look for shared physical characteristics to determine the relatedness of different species. For instance, a cladogram will show a relationship between amphibians, mammals, turtles, lizards, and birds since these apparently disparate groups share the trait of having 'four limbs with movable joints surrounded by muscle', making them tetrapods. A group of related species such as the tetrapods is called a "clade". Within the tetrapod group only lizards and birds display yet another trait: "two openings in the skull behind the eye". Lizards and birds therefore represent a smaller, more closely related clade known as diapsids. In a cladogram the evolutionary appearance of a new trait for the first time is known as a "node". Throughout the fossil halls the nodes are carefully marked along the evolutionary path and these nodes alert us to the appearance of new traits representing whole new branches of the evolutionary tree. Species showing these traits are on display in alcoves on either side of the path. A video projection on the museum's fourth floor introduces visitors to the concept of the cladogram, and is popular among children and adults alike.

Many of the fossils on display represent unique and historic pieces that were collected during the museum's golden era of worldwide expeditions (1880s–1930s).[8] On a smaller scale, expeditions continue into the present and have resulted in additions to the collections from Vietnam, Madagascar, South America, and central and eastern Africa.

The 4th floor includes the following halls:[74]

- Hall of Vertebrate Origins

- Hall of Saurischian dinosaurs (recognized by their grasping hand, long mobile neck, and the downward/forward position of the pubis bone, they are forerunners of the modern bird)[75]

- Hall of Ornithischian Dinosaurs (defined for a pubic bone that points toward the back)

- Hall of Primitive Mammals

- Hall of Advanced Mammals

Fossils on display

The many outstanding fossils on display include, among others:

- Tyrannosaurus rex: Composed almost entirely of real fossil bones, it is mounted in a horizontal stalking pose beautifully balanced on powerful legs. The specimen is actually composed of fossil bones from two T. rex skeletons discovered in Montana in 1902 and 1908 by famous dinosaur hunter Barnum Brown.[76]

- Mammuthus: Larger than its relative the woolly mammoth, these fossils are from an animal that lived 11,000 years ago in Indiana.[77]

- Apatosaurus or Brontosaurus: This giant specimen was discovered at the end of the 19th century. Although most of its fossil bones are original, the skull is not, since none was found on site. It was only many years later that the first Apatosaurus skull was discovered, and so a plaster cast of that skull was made and placed on the museum's mount. A Camarasaurus skull had been used mistakenly until a correct skull was found.[78] It is not entirely certain whether this specimen is a Brontosaurus or an Apatosaurus, and therefore it is considered an "unidentified apatosaurine", as it could also potentially be an Amphicoelias or Atlantosaurus specimen.

- Brontops: Extinct mammal distantly related to the horse and rhinoceros. It lived 35 million years ago in what is now South Dakota. It is noted for its magnificent and unusual pair of horns.[79]

- A skeleton of Edmontosaurus annectens, a large herbivorous ornithopod dinosaur. The specimen is an example of a "mummified" dinosaur fossil in which the soft tissue and skin impressions were imbedded in the surrounding rock. The specimen is mounted as it was found, lying on its side with its legs drawn up and head drawn backwards.[80]

- On September 26, 2007, an 80-million-year-old, 2-foot (61 cm) diameter fossil of an ammonite, which is composed entirely of the gemstone ammolite, made its debut at the museum. Neil Landman, curator of fossil invertebrates, explained that ammonites (shelled cephalopod mollusks in the subclass Ammonoidea) became extinct 66 million years ago, in the same extinction event that killed the dinosaurs. Korite International donated the fossil after its discovery in Alberta, Canada.[81]

- One skeleton of an Allosaurus scavenging from an Apatosaurus corpse.[82]

- The only known skull of Andrewsarchus mongoliensis.[83]

A Triceratops and a Stegosaurus are also both on display, among many other specimens.

Besides the fossils in museum display, many specimens are stored in the collections available for scientists. Those include important specimens such as complete diplodocid skull,[84] tyrannosaurid teeth, sauropod vertebrae, and many holotype.

Rose Center for Earth and Space

The Hayden Planetarium, connected to the museum, is now part of the Rose Center for Earth and Space, housed in a glass cube containing the spherical Space Theater, designed by James Stewart Polshek.[85] The Heilbrun Cosmic Pathway is one of the most popular exhibits in the Rose Center, which opened February 19, 2000.[61]

The original Hayden Planetarium was founded in 1933 with a donation by philanthropist Charles Hayden. Opened in 1935,[86] it was demolished and replaced in 2000 by the $210 million Frederick Phineas and Sandra Priest Rose Center for Earth and Space. Designed by James Stewart Polshek, the new building consists of a six-story high glass cube enclosing a 87-foot (27 m) illuminated sphere that appears to float—although it is actually supported by truss work. James Polshek has referred to his work as a "cosmic cathedral".[87] The Rose Center and its adjacent plaza, both located on the north facade of the museum, are regarded as some of Manhattan's most outstanding recent architectural additions. The facility encloses 333,500 square feet (30,980 m2) of research, education, and exhibition space as well as the Hayden planetarium. Also located in the facility is the Department of Astrophysics, the newest academic research department in the museum. Neil DeGrasse Tyson is the director of the Hayden Planetarium. Further, Polshek designed the 1,800-square-foot (170 m2) Weston Pavilion, a 43-foot (13 m) high transparent structure of "water white" glass along the museum's west facade. This structure, a small companion piece to the Rose Center, offers a new entry way to the museum as well as opening further exhibition space for astronomically related objects. The planetarium's former magazine, The Sky, merged with "The Telescope", to become the astronomy magazine Sky & Telescope.[88]

Tom Hanks provided the voice-over for the first planetarium show during the opening of the new Rose Center for Earth & Space in the Hayden Planetarium in 2000. Since then such celebrities as Whoopi Goldberg, Robert Redford, Harrison Ford and Maya Angelou have been featured.[89][90]

Exhibitions Lab

Founded in 1869, the AMNH Exhibitions Lab has since produced thousands of installations. The department is notable for its integration of new scientific research into immersive art and multimedia presentations. In addition to the famous dioramas at its home museum and the Rose Center for Earth and Space, the lab has also produced international exhibitions and software such as the Digital Universe Atlas.[91]

The exhibitions team currently consists of over sixty artists, writers, preparators, designers and programmers. The department is responsible for the creation of two to three exhibits per year. These extensive shows typically travel nationally to sister natural history museums. They have produced, among others, the first exhibits to discuss Darwinian evolution,[62] human-induced climate change[92] and the mesozoic mass extinction via asteroid.

Research Library

The Research Library is open to staff and public visitors, and is located on the fourth floor of the museum.[93]

The Library collects materials covering such subjects as mammalogy, earth and planetary science, astronomy and astrophysics, anthropology, entomology, herpetology, ichthyology, paleontology, ethology, ornithology, mineralogy, invertebrates, systematics, ecology, oceanography, conchology, exploration and travel, history of science, museology, bibliography, genomics, and peripheral biological sciences. The collection is rich in retrospective materials — some going back to the 15th century — that are difficult to find elsewhere.[94]

History

In its early years, the Library expanded its collection mostly through such gifts as the John C. Jay conchological library, the Carson Brevoort library on fishes and general zoology, the ornithological library of Daniel Giraud Elliot, the Harry Edwards entomological library, the Hugh Jewett collection of voyages and travel and the Jules Marcou geology collection. In 1903 the American Ethnological Society deposited its library in the museum and in 1905 the New York Academy of Sciences followed suit by transferring its collection of 10,000 volumes.

Today, the Library's collections contain over 550,000 volumes of monographs, serials, pamphlets, reprints, microforms, and original illustrations, as well as film, photographic, archives and manuscripts, fine art, memorabilia and rare book collections.

The new Library was designed by the firm Roche-Dinkeloo in 1992. The space is 55,000 sq ft (5,100 m2) and includes five different 'conservation zones', ranging from the 50-person reading room and public offices, to temperature and humidity controlled rooms.[95]

Special collections

- Institutional Archives, Manuscripts, and Personal Papers: Includes archival documents, field notebooks, clippings and other documents relating to the museum, its scientists and staff, scientific expeditions and research, museum exhibitions, education, and general administration.[96]

- Art and Memorabilia Collection.[97]

- Moving Image Collection.[98]

- Vertical Files: Relating to exhibitions, expeditions, and museum operations.[99]

Activities offered

Research activities

The museum has a scientific staff of more than 225, and sponsors over 120 special field expeditions each year. Many of the fossils on display represent unique and historic pieces that were collected during the museum's golden era of worldwide expeditions (1880s–1930s). Examples of some of these expeditions, financed in whole or part by the AMNH are: Jesup North Pacific Expedition, the Whitney South Seas Expedition, the Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition, the Crocker Land Expedition, and the expeditions to Madagascar and New Guinea by Richard Archbold. On a smaller scale, expeditions continue into the present. The museum also publishes several peer-reviewed journals, including the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History.[100] In 1976, animal rights activist Henry Spira led a campaign against vivisection on cats that the American Museum of Natural History had been conducting for 20 years, intended to research the impact of certain types of mutilation on the sex lives of cats. The museum halted the research in 1977.[citation needed]

Educational outreach

AMNH's education programs include outreach to schools in New York City by the Moveable Museum.[101]

Additionally, the Museum itself offers a wide variety of educational programs, camps, and classes for students from pre-K to post-graduate levels. Notably, the Museum sponsors the Lang Science Program, a comprehensive 5th-12th grade research and science education program, and the Science Research Mentorship Program (SRMP), among the most prestigious paid internships in NYC, in which pairs of students conduct a full year of intensive original research with an AMNH scientist.[102]

Richard Gilder Graduate School

The AMNH offers a Master of Arts in Science Teaching and a PhD in Comparative Biology.[103][104]

On October 23, 2006, the museum launched the Richard Gilder Graduate School, which offers a PhD in Comparative Biology, becoming the first American museum in the United States to award doctoral degrees in its own name. Accredited in 2009, in 2011 the graduate school had 11 students enrolled, who work closely with curators and they have access to the collections.[105][106][107] The first seven graduates to complete the program were awarded their degrees on September 30, 2013.[108] The dean of the graduate school is AMNH paleontologist John J. Flynn, and the namesake and major benefactor is Richard Gilder.

Southwestern Research Station

The AMNH operates a biological field station in Portal, Arizona, among the Chiricahua Mountains. The Southwestern Research Station was established in 1955, purchased with a grant from philanthropist David Rockefeller, and with entomologist Mont Cazier as its first director.[109] The station, located in a "biodiversity hotspot," is used by researchers and students, and offers occasional seminars to the public.[110]

Surroundings

The museum is located at 79th Street and Central Park West, accessible via the B and C trains of the New York City Subway. There is a low-level floor direct access into the museum via the 81st Street–Museum of Natural History subway station on the IND Eighth Avenue Line at the south end of the upper platform (where uptown trains arrive).

On a pedestal outside the museum's Columbus Avenue entrance is a stainless steel time capsule, which was created after a design competition that was won by Santiago Calatrava. The capsule was sealed at the beginning of 2000, to mark the beginning of the 3rd millennium. It takes the form of a folded saddle-shaped volume, symmetrical on multiple axes, that explores formal properties of folded spherical frames. Calatrava described it as "a flower". The plan is that the capsule will be opened in the year 3000.[111]

The museum is situated in a 17-acre (69,000 m2) city park known as Theodore Roosevelt Park. The park extends from Central Park West to Columbus Avenue, and from West 77th to 81st Streets. Theodore Roosevelt Park contains park benches, gardens and lawns, and also a dog run.[112]

The Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt is located outside the museum facing Central Park West and is subject to removal due the subordinate depiction of African American and Native American figures behind Roosevelt.[113]

In popular culture

Literature

- In J. D. Salinger's novel The Catcher in the Rye, the protagonist Holden Caulfield at one point finds himself heading towards the museum, reflecting on past visits and remarking that what he likes is the permanence of the exhibits there.[114]

- The museum was the setting for the 1970 novel The Great Dinosaur Robbery by David Forrest, but was not featured in the film adaptation One of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing, which was set in the Natural History Museum in London, England.

- The novel Funny Bananas: The Mystery in the Museum, by Georgess McHargue (1975), features the museum.

- The novel Ritual, by William Heffernan (1989), features the museum.

- The novel Murder at the Museum of Natural History, by Michael Jahn (1994), features the museum.

- As the "New York Museum of Natural History", the museum is a favorite setting in many Douglas Preston and Lincoln Child novels, including Relic (1995), Reliquary (1997), The Cabinet of Curiosities (2002), and The Book of the Dead (2007). FBI Special Agent Aloysius X. L. Pendergast plays a major role in all of these thrillers. Preston was manager of publications at the museum before embarking upon his fiction writing career.

- The novel The Bone Vault, by Linda Fairstein (2003), features the museum.

- The museum has appeared repeatedly in the fiction of dark fantasy author Caitlín R. Kiernan, including appearances in her fifth novel Daughter of Hounds, her work on the DC/Vertigo comic book The Dreaming (#47, "Trinket"), and many of her short stories, including "Valentia" and "Onion" (both collected in To Charles Fort, With Love, 2005).

- In Mirage's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, Michelangelo acts as a tour guide for visiting aliens. His first assignment is the Saurian Regenta Seri and her Styracodon bodyguards who wish to see the museum, specifically the dinosaur exhibit.

- The novel Wood Sprites, by Wen Spencer (2014), features the museum.

Film

- A large portion of the 2017 film Wonderstruck takes place in the museum, showing the museum in 1927 as well as 1977.

- The museum in the film Night at the Museum (2006) is based on a 1993 book that was set at the AMNH (The Night at the Museum). The interior scenes were shot at a sound stage in Vancouver, British Columbia, but exterior shots of the museum's façade were done at the actual AMNH. AMNH officials have credited the movie with increasing the number of visitors during the holiday season in 2006 by almost 20 percent. According to museum president Ellen Futter, there were 50,000 more visits over the previous year during the 2006 holiday season.[115] Its sequels, Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian (2009) and Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014), were also partially set in this museum.

- The exterior of AMNH was used in a benefit party scene in the 2006 film The Devil Wears Prada.

- The 2005 movie The Squid and the Whale takes its name from the diorama of the giant squid and the sperm whale in the museum's Hall of Ocean Life. The diorama is shown in the film's final scene.

- The AMNH is featured in the 1998 film An American Tail: The Treasure of Manhattan Island. Fievel Mousekewitz and Tony Toponi go to the AMNH to meet Dr. Dithering to decipher a treasure map they have found in an abandoned subway.

- An ending for the 1993 film We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story shows all four dinosaurs finally reaching the AMNH.

- Late in the 1984 film Splash Tom Hanks's character is ejected from a laboratory whose entrance is clearly located under the stairs that lead the public to the lower floor of the AMNH's Hall of Ocean Life.

- Scenes from the horror film Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) and the biographic film Malcolm X (1992) were filmed in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals.

- In the 1955 Czechoslovak film, Journey to the Beginning of Time, (Czech: Cesta do pravěku, literally "Journey into prehistory") the four boys end their journey on a bench inside the AMNH's 77th St. entrance, beneath the exhibit of the long-boat, in which they'd had their adventure. While the story could be dismissed as a dream, one boy's journal has somehow suffered all the wear-&-tear of their journey through prehistoric eras. A dubbed and partly re-filmed US version of the film was released in 1966 under the title 'Journey to the Beginning of Time'.

- An early scene of Howard Hawke's 1938 film Bringing Up Baby is set in the museum.

- The 1914 popular silent cartoon Gertie the Dinosaur was set in the Museum.

Television

- In 2009, the museum hosted the live finale of the second season of The Celebrity Apprentice.

- In early seasons of Friends, Ross Geller works at the museum.

- The museum is featured in the How I Met Your Mother episode Natural History, although it is renamed the Natural History Museum.

- An episode of Mad About You, titled "Natural History", is set in the museum.

- In a second-season episode of The Spectacular Spider-Man titled "Destructive Testing", Spider-Man fights Kraven the Hunter in the museum.

- In many episodes of the Time Warp Trio on Discovery Kids, Joe, Sam, and Fred are in the museum; in one episode they see it 90 years into the future.

- In the episode Top Chef: All-Stars, "Night at the Museum", both the Quickfire Challenge and Elimination Challenge required the chef contestants to cook at the American Museum of Natural History.

- The museum has made many appearances in The Penguins of Madagascar.

Video games

- The AMNH is featured in the video game Grand Theft Auto IV and Episodes from Liberty City expansions The Lost and Damned and The Ballad of Gay Tony where it is known as the Liberty State Natural History Museum.

- The AMNH appears as a Resistance-controlled building in the Sierra game Manhunter: New York.

- Portions of the Sony PlayStation game Parasite Eve take place within the AMNH.

Gallery

-

Bengal tiger at the American Museum of Natural History

-

Diorama in Akeley Hall of African Mammals

-

Diorama in Akeley Hall of African Mammals

-

Diorama in Akeley Hall of African Mammals

-

Butterfly Conservatory

-

Display in Milstein Hall of Ocean Life

-

Tibetan Kalachakra statue

-

The museum's south range, and some of the west façade, in the 1920s

-

American bison and pronghorn diorama (right)

-

Night view of the museum, looking northwest from across Central Park West

See also

- Education in New York City

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- Margaret Mead Film Festival

- Constantin Astori

References

- ^ a b "History 1869-1900". AMNH.

- ^ "TEA-AECOM 2018 Theme Index and Museum Index: The Global Attractions Attendance Report" (PDF). Themed Entertainment Association. pp. 62–77. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ "NPS Focus". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Dioramas at the Museum: Millions of Specimens in Context". Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ "American Museum of Natural History - Overview and Programs". Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ "No. 7 American Museum of Natural History, New York City". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Mission Statement". AMNH. Archived from the original on December 14, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ a b "Timeline: The History of the American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ a b c Preston, Douglas (1986). Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion into the American Museum of Natural History. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-10456-1.

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (July 29, 2007). "The Face Will Still Be Forbidding, But Much Tighter and Cleaner". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (April 2, 2006). "Shoring Up a Castle Wall". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Newland, D. H. (January 1916). "The Quarry Materials of New York—Granite, Gneiss, Trap and Marble". New York State Museum Bulletin (181): 75.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (January 27, 1995). "Natural History Museum Plans Big Overhaul". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ "Permanent Exhibitions". Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Collins, Glenn (December 1, 1991). "Clearing a New Path for T. Rex and Company". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Barron, James (June 20, 2010). "Teddy Is Restored. In Paint, at Least". City Room. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Museum of Natural History Reveals Design for Expansion". The New York Times. November 5, 2015. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (December 11, 2014). "American Museum of Natural History Plans an Addition". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Wachs, Audrey (October 11, 2016). "Landmarks Commission approves Natural History Museum expansion". Archpaper.com. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "Natural History Museum files plans for Gilder Center expansion". Real Estate Weekly. August 14, 2017. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Appel, Alex (June 13, 2019). "American Museum of Natural History Launches $383M Expansion". Commercial Observer. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ "American Museum of Natural History to break ground on new center". am New York. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Timeline: The History of the American Museum of Natural History". Retrieved November 7, 2009.

- ^ a b "Full text of "General guide to the exhibition halls of the American Museum of Natural History"". Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Revisiting Akeley's Gorillas". YouTube. February 16, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Painting Actuality: Chapter 5: 1934: Joining the American Museum of Natural History". Peabody.yale.edu. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (October 26, 2012). "Roosevelt’s Elephant". nytimes.com

- ^ Wolfgang Saxon (October 25, 1995). "W.D. Campbell, 88; Promoted Scouting In the Third World - New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Akeley Hall of African Mammals". Amnh.org. May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Painting Actuality: Chapter 6: The African Hall". Peabody.yale.edu. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Hall of Asian Mammals". Amnh.org. May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Explorers hunt for pink duck". Kingston Daily Freeman. October 11, 1923.

- ^ Explorer Embarks on Long Journey to Search for Rare Wild Animals Lawrence Journal- January 17, 1924

- ^ Nina Gregorev. "Vernay-Hopwood Chindwin Expedition | Anthropology". Anthro.amnh.org. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Diorama diversity. - Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (December 10, 1929). "Movie Review - Hunting Tigers in India - THE SCREEN". NYTimes.com. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ a b "Painting Actuality: Chapter 7: Francis Lee Jaques and the American Museum of Natural History Bird Halls". Peabody.yale.edu. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge". Fws.gov. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Burden, W. Douglas (1956). Look to the Wilderness. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 169–193.

- ^ "Full text of "General guide to the exhibition halls of the American Museum of Natural History"". archive.org.

- ^ "Hall of North American Forests". AMNH.

- ^ a b "The Felix M. Warburg Memorial Hall of the American Museum of Natural History, New York City: (Pine Plains: Its Unique Natural Heritage)". ancestry.com.

- ^ "Mad men design a museum exhibit". Joseph Smith.

- ^ Retrieved October 2, 2010 Archived December 18, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Milstein Hall of Ocean Life". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ^ Retrieved October 2, 2010 Archived December 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of the Hall of Ocean Life". American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Rescuing the Diorama From the Fate of the Dodo", by Glenn Collins, New York Times, February 3, 2003

- ^ Christopher Swan. "Hall of Asian People; Orienting the Americans". CSMonitor.com. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Confluences: An American Expedition to Northern Burma, 1935" (PDF). AMNH. April 4, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ "Gardner D. Stout Hall of Asian Peoples". Amnh.org. May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Hall of African Peoples". Amnh.org. May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "Ancient Mexico and Central America". Internet Archive.

- ^ "The reopening of the Mexican and Central American hall, February 25, 1944, The American museum of natural history". Internet Archive.

- ^ "History 1961-1990". AMNH.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Brunoniana - Taylor, Will S." brown.edu.

- ^ a b "Indians of the Northwest Coast". Internet Archive.

- ^ Jesup North Pacific Expedition | Anthropology

- ^ "AMNH Special Collections — Jesup North Pacific Exhibition". amnh.org.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (November 14, 2006). "Canoe Goes Upriver, Without Its Paddlers". nytimes.com.

- ^ a b "Timeline: The History of the American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on March 10, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Osborn, Henry Fairfield (April 21, 1921). "The Hall of the Age of Man in the American Museum". Nature. 107 (2686): 236–240. Bibcode:1921Natur.107..236O. doi:10.1038/107236a0.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (February 9, 2007). "Meet the Relatives. They're Full of Surprises". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ "The AMNH Meteorites Collection". Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (September 19, 2003). "New Hall for Meteorites Old Beyond Imagining". The New York Times. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ "Arthur Ross Hall of Meteorites". Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Paul Goldberger (April 14, 1977). "Design Notebook". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Patricia Emerald". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ "Star of India". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ "Hall of Minerals and Gems". Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Hughes, Richard W. "Padparadscha and Pink Sapphire Defined". Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Montgomery, Paul (November 1, 1964). "3 Seized in Theft of Museum Gems". The New York Times.

- ^ "The AMNH Gem and Mineral Collection". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Fossil Halls". AMNH. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Considine, J. D. (April 12, 2005). "Dinosaurs that flocked together". Toronto: The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ "Fossil Halls". Archived from the original on March 12, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Fossil Halls". Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Fossil Halls". Archived from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Fossil Halls". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Hall of Ornithischian Dinosaurs". AMNH. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Dahl, Julia (September 27, 2007). "Ancient 'Snail' Is A Real Gem". New York Post. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ "Allosaurus". AMNH. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ "Andrewsarchus, "Superb Skull of a Gigantic Beast"". AMNH. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- ^ Tschopp, E., Mateus O., & Norell M. (2018). Complex Overlapping Joints between Facial Bones Allowing Limited Anterior Sliding Movements of the Snout in Diplodocid Sauropods. American Museum NovitatesAmerican Museum Novitates. 1 - 16.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (January 17, 2000). "Stairway to the Stars". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (August 16, 1996). "A Remnant of the 1930's, and Its Sky, Will Fall". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (May 8, 2000). "A cosmic cathedral on 81st Street". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Tyson, Neil deGrasse. "Hayden Planetarium and Digital Universe". American Museum of Natural History.

- ^ "DARK UNIVERSE, A NEW HAYDEN PLANETARIUM SPACE SHOW, PREMIERES NOVEMBER 2 AT AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY" (PDF). American Museum of Natural History. September 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Today we remember the inspirational Maya Angelou [AMNH blog entry]". American Museum of Natural History Blog. May 28, 2014. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "AMNH Education Exhibition". Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "In the Hall of Biodiversity". New York Times. June 1, 1998. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ "Research Library". Amnh.org. May 1, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ "AMNH Library - About the Library". Archived from the original on February 24, 2009. Retrieved March 3, 2009.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (November 7, 1992). "Handling the (Fragile) Story of Man With Care; Museum of Natural History Library Moves Its Million-Item Collection to a New Home". The New York Times.

- ^ "Institutional Archives, Manuscripts, and Personal Papers". Amnh.org. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Art and Memorabilia- AMNH.org

- ^ Moving Image Collection- AMNH.org

- ^ Vertical Files- AMNH.org

- ^ AMNH Scientific Publications, American Museum of Natural History, Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Jimmy Van Bramer brings Moveable Museum to Queensbridge for Family Day" (PDF). Woodside Herald. June 25, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"The Moveable Museum". Edwize.org. November 3, 2010. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"American Museum of Natural History 2009 Annual Report" (PDF). The American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"American Museum of Natural History Moveable Museum Program "Discovering the Universe" visits P.S. 225". NYC Department of Education. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"Moveable Museums Make Trip to D.C. (video)". AMNH Youtube Channel. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"Moveable Museum". National Lab Day. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"Moveable Museum". Stuyvesant Town Events. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"At Staten Island School, a Moving Way to Learn". SILive.com. October 3, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"Dinosaurs, Moveable Museums, and Science!". United States Department of Education. November 8, 2010. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"American Museum Of Natural History Brings Dinosaurs "Exhibit-On-Wheels" To Local Preschoolers". Educational Alliance. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"AMNH Moveable at Family Fun Day". Family Health Resource Center & Patient Library. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

"M.O.N.H. Moveable Museum". ColoriumLaboratorium. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved December 3, 2010. - ^ "AMNH - Learn and Teach".

- ^ "AMNH Master of Arts in Teaching". AMNH. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ "Richard Gilder Graduate School, School Overview". AMNH. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ Lewin, Tamar (July 22, 2011). "The Critter People". The New York Times.

- ^ "First US Museum to Award Ph.D. Degree: Dean John Flynn Assumes Helm at Richard Gilder Graduate School at AMNH". Education Update Online. February 2009.