All the President's Men (film)

| All the President's Men | |

|---|---|

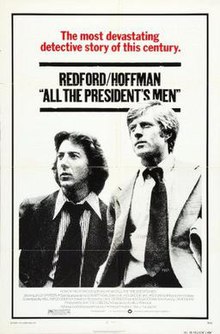

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Screenplay by | William Goldman |

| Based on | All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein Bob Woodward |

| Produced by | Walter Coblenz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by | Robert L. Wolfe |

| Music by | David Shire |

Production company | Wildwood Enterprises |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $8.5 million |

| Box office | $70.6 million[1] |

All the President's Men is a 1976 American political thriller film about the Watergate scandal, which brought down the presidency of Richard M. Nixon. Directed by Alan J. Pakula with a screenplay by William Goldman, it is based on the 1974 non-fiction book of the same name by Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, the two journalists investigating the Watergate scandal for The Washington Post. The film stars Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman as Woodward and Bernstein, respectively; it was produced by Walter Coblenz for Redford's Wildwood Enterprises.

The film was nominated in multiple Oscar, Golden Globe and BAFTA categories, and, in 2010, was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[2][3]

Plot

On June 17, 1972, security guard Frank Wills at the Watergate complex finds a door's bolt taped over so that it will not lock. He calls the police, who find and arrest five burglars in the Democratic National Committee headquarters within the complex. The next morning, The Washington Post assigns new reporter Bob Woodward to the local courthouse to cover the story, which is considered of minor importance.

Woodward learns that the five men, four Cuban-Americans from Miami and James W. McCord, Jr., had electronic bugging equipment and are represented by a high-priced "country club" attorney. At the arraignment, McCord identifies himself in court as having recently left the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the others are also revealed to have CIA ties. Woodward connects the burglars to E. Howard Hunt, a former employee of the CIA, and President Richard Nixon's White House Counsel, Charles Colson.

Carl Bernstein, another Post reporter, is assigned to cover the Watergate story with Woodward. The two young men are reluctant partners, but work well together. Executive editor Benjamin Bradlee believes their work lacks reliable sources and is not worthy of the Post's front page, but he encourages further investigation.

Woodward contacts a senior government official, an anonymous source whom he has used before and refers to as "Deep Throat." Communicating secretly, using a flag placed in a balcony flowerpot to signal meetings, they meet at night in an underground parking garage. Deep Throat speaks in riddles and metaphors, avoiding substantial facts about the Watergate break-in, but keeps advising Woodward to "follow the money".

Woodward and Bernstein manage to connect the five burglars to corrupt activities around campaign contributions to Nixon's Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP or, more common at the time, CREEP). This includes a check for $25,000 paid by Kenneth H. Dahlberg, whom Miami authorities identified when investigating the Miami-based burglars. Still, Bradlee and others at the Post doubt the investigation and its dependence on sources such as Deep Throat, wondering why the Nixon administration should break the law when the President is almost certain to defeat his opponent, Democratic nominee George McGovern.

Through former CREEP treasurer Hugh W. Sloan, Jr., Woodward and Bernstein connect a slush fund of hundreds of thousands of dollars to White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman—"the second most important man in this country"—and to former Attorney General John N. Mitchell, now head of CREEP. They learn that CREEP was financing a "ratfucking" campaign to sabotage Democratic presidential candidates a year before the Watergate burglary, when Nixon was lagging Edmund Muskie in the polls.

While Bradlee's demand for thoroughness compels the reporters to obtain other sources to confirm the Haldeman connection, the White House issues a non-denial denial of the Post's above-the-fold story. The editor continues to encourage investigation.

Woodward again meets secretly with Deep Throat, and demands he be less evasive. Deep Throat reveals that Haldeman masterminded the Watergate break-in and cover-up. He also states that the cover-up was not just to camouflage the CREEP involvement but to hide "covert operations" involving "the entire U.S. intelligence community", including the CIA and FBI. He warns Woodward and Bernstein that their lives, and others, are in danger. When the two relay this to Bradlee, he urges them to carry on despite the risk from Nixon's re-election.

On January 20, 1973, Bernstein and Woodward type the full story, while a television in the foreground shows Nixon taking the Oath of Office for his second term as President. A montage of Watergate-related teletype headlines from the following year is shown, ending with Nixon's resignation and the inauguration of Vice President Gerald Ford on August 9, 1974.

Cast

- Robert Redford as Bob Woodward

- Dustin Hoffman as Carl Bernstein

- Jack Warden as Harry M. Rosenfeld

- Martin Balsam as Howard Simons

- Hal Holbrook as "Deep Throat"

- Jason Robards as Ben Bradlee

- Jane Alexander as Judy Hoback Miller

- Stephen Collins as Hugh W. Sloan, Jr.

- Ned Beatty as Martin Dardis

- Meredith Baxter as Deborah Murray Sloan

- Penny Fuller as Sally Aiken (based on Marilyn Berger)[4]

- Penny Peyser as Sharon Lyons

- Lindsay Crouse as Kay Eddy

- Robert Walden as Donald Segretti

- F. Murray Abraham as Sgt. Paul Leeper

- David Arkin as Eugene Bachinski

- Richard Herd as James W. McCord, Jr. (Watergate Burglar)

- Henry Calvert as Bernard Barker (Watergate Burglar)

- Dominic Chianese as Eugenio Martínez (Watergate Burglar)

- Ron Hale as Frank Sturgis (Watergate Burglar)

- Nate Esformes as Virgilio R. Gonzales (Watergate Burglar)

- Nicolas Coster as Markham

- Joshua Shelley as Al Lewis

- Ralph Williams as Ray Steuben

- Gene Lindsey as Alfred D. Baldwin

- Polly Holliday as Dardis' secretary

- Carol Trost as Ben Bradlee's secretary

- James Karen as Hugh Sloan's attorney

- Basil Hoffman as Assistant Metro Editor

- Stanley Bennett Clay as Assistant Metro Editor

- John McMartin as Foreign Editor

- John Devlin as Metro Editor

- Paul Lambert as National Editor

- Richard Venture as Assistant Metro Editor

- John Furlong as News Desk Editor

- Valerie Curtin as Miss Milland

- Jess Osuna as Joe (FBI agent)

- Allyn Ann McLerie as Carolyn Abbott

- Christopher Murray as Photo Aide

- Frank Wills as himself (the actual security guard at the Watergate complex)

- Cara Duff-MacCormick as Tammy Ulrich (uncredited)

- John Randolph as John Mitchell (voice) (uncredited)

Differences from the book

Unlike the book, the film covers only the first seven months of the Watergate scandal, from the time of the break-in to Nixon's second inauguration on January 20, 1973.[5] The film introduced the catchphrase "follow the money" in relation to the case, which did not appear in the book or any documentation of Watergate.[6]

Production

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

Robert Redford bought the rights to Woodward and Bernstein's book in 1974 for $450,000 with the notion to adapt it into a film with a budget of $5 million.[7] Ben Bradlee, executive editor of the Washington Post, realized that the film was going to be made regardless of whether he approved of it and believed that it made "more sense to try to influence it factually".[7] He hoped that the film would show newspapers "strive very hard for responsibility".[7]

William Goldman was hired by Redford to write the script in 1974. He said Bob Woodward was extremely helpful to him but Carl Bernstein was not. Goldman wrote that his crucial decision as to structure was to throw away the second half of the book.[8] After he delivered his first draft in August 1974, Warners agreed to finance the movie.

Redford said he was not happy with Goldman's first draft.[7] Woodward and Bernstein also read it and did not like it. Redford asked for their suggestions, but Bernstein and his girlfriend, writer Nora Ephron, wrote their own draft. Redford showed this draft to Goldman, suggesting there might be some material he could use; Goldman later called Redford's acceptance of the Bernstein–Ephron draft a "gutless betrayal".[9] Redford later expressed dissatisfaction with the Ephron–Bernstein draft, saying, "a lot of it was sophomoric and way off the beat".[7] According to Goldman, "in what they wrote, Bernstein was sure catnip to the ladies".[9] He also says a scene of Bernstein and Ephron's made it to the final film, a bit where Bernstein outfakes a secretary in order to see someone—something that was not factually true.

Alan J. Pakula was hired to direct and requested rewrites from Goldman. In a 2011 biography, Redford claimed that he and Pakula held all-day sessions working on the script. The director also spent hours interviewing editors and reporters, taking notes of their comments.

Later in 2011, Richard Stayton published an investigative article debunking the claims that the material Pakula and Redford rewrote for the screenplay was significant to the finished film. Stayton, who published his report in Written By magazine, compared several drafts of the script, including the final production draft. He concluded that Goldman was properly credited as the writer and that the final draft had "William Goldman's distinct signature on each page".[10]

Casting

Redford first selected Al Pacino to play Bernstein, but after some thought, he decided that Dustin Hoffman was a better fit for the role.

Jason Robards was always Redford's choice to play Ben Bradlee. Bradlee initially recommended George C. Scott for the role, and he was somewhat unimpressed when Robards showed up at the Post offices to develop a feel for the newsroom. In advance of the shoot, Bradlee told Robards: "Just don't make me look like an asshole". At first, Pakula was worried that Robards could not carry Bradlee's easy elegance and command authority. Karl Malden, Hal Holbrook (who would play Deep Throat), John Forsythe, Leslie Nielsen, Henry Fonda, Richard Widmark, Christopher Plummer, Anthony Quinn, Gene Hackman, Burt Lancaster, Robert Stack, Robert Mitchum and Telly Savalas were also considered for the role.[11]

Character actor Martin Balsam played managing editor Howard Simons. According to Bradlee, Simons felt that he and his role were fatally shortchanged in the script and that he never got over his resentment.

Bradlee teased The Post publisher Katharine Graham about who would play her in the film. "Names like Katharine Hepburn, Lauren Bacall and Patricia Neal were tossed out—by us—to make her feel good," Bradlee said. "And names like Edna May Oliver or Marie Dressler, if it felt like teasing time. And then her role was dropped from the final script, half to her relief."[12]

Filming

Hoffman and Redford visited The Washington Post's offices for months, sitting in on news conferences and conducting research for their roles.[7] As the Post denied the production permission to shoot in its newsroom, set designers took measurements of the newspaper's offices, and photographed everything. Boxes of trash were gathered and transported to sets recreating the newsroom on two soundstages in Hollywood's Burbank Studios at a cost of $200,000. The filmmakers went to great lengths for accuracy and authenticity, including making replicas of outdated phone books.[7] Nearly 200 desks at $500 a piece were purchased from the same firm that sold desks to the Post in 1971. The desks were painted the same color as those of the newsroom. The production was supplied with a brick from the main lobby of the Post so that it could be duplicated in fiberglass for the set. Principal photography began on May 12, 1975, in Washington, D.C.[7]

The billing followed the formula of James Stewart and John Wayne in John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), with Redford billed over Hoffman in the posters and trailers, and Hoffman billed above Redford in the film itself.[citation needed]

Reception

Box office

All the President's Men grossed $70.6 million at the box office.[1]

Critical response

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes it has an approval rating of 93% based on 60 reviews, with an average rating of 9.08/10. The website's consensus reads: "A taut, solidly acted paean to the benefits of a free press and the dangers of unchecked power, made all the more effective by its origins in real-life events."[13] On Metacritic, which gives a weighted average score, the film has a score of 80 out of 100, based on reviews from 13 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[14]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave it 3+1⁄2 stars out of 4, and wrote: "It provides the most observant study of working journalists we're ever likely to see in a feature film. And it succeeds brilliantly in suggesting the mixture of exhilaration, paranoia, self-doubt, and courage that permeated The Washington Post as its two young reporters went after a presidency."[15] Variety magazine praised "ingenious direction [...] and scripting" which overcame the difficult lack of drama that a story about reporters running down a story might otherwise have.[16] Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader was critical of the writing and called the film "pedestrian" and "a study in missed opportunities."[17]

Accolades

In 2007, it was added to the AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list at No. 77. AFI also named it No. 34 on its America's Most Inspiring Movies list and No. 57 on the Top 100 Thrilling Movies. The characters of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein shared the rank of No. 27 (Heroes) on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains list. Entertainment Weekly ranked All the President's Men as one of its 25 "Powerful Political Thrillers".[18]

In 2015, The Hollywood Reporter polled hundreds of Academy members, asking them to re-vote on past controversial decisions. Academy members indicated that, given a second chance, they would award the 1977 Oscar for Best Picture to All the President's Men instead of Rocky.[19]

| Award | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[20][21] | |||

| Best Art Direction | Art Direction: George Jenkins; Set Decoration: George Gaines |

Won | |

| Best Director | Alan J. Pakula | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Robert L. Wolfe | ||

| Best Picture | Walter Coblenz | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | William Goldman | Won | |

| Best Sound | Arthur Piantadosi, Les Fresholtz, Dick Alexander and James E. Webb | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Jane Alexander | Nominated | |

| American Cinema Editors (ACE) | Best Edited Feature Film | Robert L. Wolfe | |

| BAFTA Film Awards | Best Actor | Dustin Hoffman | |

| Best Cinematography | Gordon Willis | ||

| Best Director | Alan J. Pakula | ||

| Best Film | |||

| Best Editing | Robert L. Wolfe | ||

| Best Production Design/Art Direction | George Jenkins | ||

| Best Screenplay | William Goldman | ||

| Best Sound Track | Arthur Piantadosi James E. Webb Les Fresholtz Dick Alexander Milton C. Burrow | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Martin Balsam | ||

| Directors Guild of America | Outstanding Directorial Achievement | Alan J. Pakula | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Director | Alan J. Pakula | |

| Best Picture | |||

| Best Screenplay | William Goldman | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | ||

| Kansas City Film Critics | Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | Won |

| National Board of Review | Best Director | Alan J. Pakula | |

| Top 10 Films of the Year | 1st place | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | Won | |

| New York Film Critics | Best Director | Alan J. Pakula | |

| Best Film | |||

| Best Supporting Actor | Jason Robards | ||

| Writers Guild of America (WGA) | Best Adapted Screenplay | ||

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills – #57

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains:

- Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein – #27 Heroes

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes

- "Follow the money." – Nominated.

- AFI's100 Years...100 Cheers – #34

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies: 10th Anniversary Edition– #77

"All The President's Men" Revisited

Sundance Productions, which Redford owns, produced a two-hour documentary entitled "All The President's Men" Revisited.[22] Broadcast on Discovery Channel Worldwide on March 24, 2013, the documentary focuses on the Watergate case and the subsequent film adaptation. It simultaneously recounts how The Washington Post broke Watergate and how the scandal unfolded, going behind the scenes of the film. It explores how the Watergate scandal would be covered in the present day, whether such a scandal could happen again, and who Richard Nixon was as a man. W. Mark Felt, Deputy Director of the FBI during the early 1970s, revealed in 2005 his role as Deep Throat during the investigation; this is also covered.

Footage from the film is used, as well as interviews with Redford and Hoffman as well as actual central characters including Woodward, Bernstein, Bradlee, John Dean and Alexander Butterfield. Contemporary media figures such as Tom Brokaw, Jill Abramson, Rachel Maddow and Jon Stewart also are featured in the documentary, which earned a 2013 Emmy nomination for Outstanding Documentary Or Nonfiction Special.[23][24]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "All the President's Men, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "Hollywood Blockbusters, Independent Films and Shorts Selected for 2010 National Film Registry". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ^ Reeling Back assessed 8-2-2015

- ^ "Differences between All the President's Men Book vs Movie". thatwasnotinthebook.com. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- ^ Shapiro, Fred (2011-09-23). "Follow the Money". Freakonomics. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shales, Tom; Tom Zito; Jeannette Smyth (April 11, 1975). "When Worlds Collide: Lights! Camera! Egos!". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ^ Goldman 1982, p. 235

- ^ a b Goldman 1982, p. 240

- ^ Stayton, Richard. "Fade In". Written By. WGA.

- ^ Himmelman, Jeff (2012). "Yours in Truth: A Personal Portrait of Ben Bradlee, Legendary Editor of The Washington Post". Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-679-60364-1.

- ^ "Ben Bradlee: Iconic Editor".

- ^ All the President's Men at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ All the President's Men at Metacritic

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1976). "All the President's Men". RogerEbert.com.

- ^ "All the President's Men". Variety. December 31, 1975.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. "All the President's Men". Chicago Reader.

- ^ "Democracy 'n' Action: 25 Powerful Political Thrillers". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ^ "Recount! Oscar Voters Today Would Make 'Brokeback Mountain' Best Picture Over 'Crash'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2020-01-03.

- ^ "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ^ "NY Times: All the President's Men". NY Times. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ^ "Watergate subject for Redford-owned Sundance Productions"[permanent dead link], Chicago Tribune, 3 April 2012

- ^ Bauder, David (March 20, 2013). "'All the President's Men Revisited' Documentary To Air On Discovery". The Huffington Post. AOL. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ The Primetime Emmys – All The President's Men Revisted The Emmys

References

- Goldman, William (1982). Adventures in the Screen Trade. Warner Books.

External links

- All The President's Men essay by Mike Canning at National Film Registry [1]

- All the President's Men at IMDb

- All the President's Men at the TCM Movie Database

- Template:Allrovi movie

- All the President's Men at Box Office Mojo

- All the President's Men at Rotten Tomatoes

- Slovick, Matt (1996). "'All the President's Men'". The Washington Post.

- "Cinema: Watergate on Film". Time. March 29, 1976.

- Lyman, Rick (February 16, 2001). "WATCHING MOVIES WITH/Steven Soderbergh; Follow the Muse: Inspiration To Balance Lofty and Light". The New York Times.

- Savlov, Marc (April 15, 2011). "From the Watergate Break-in to a Broken News Media". The Austin Chronicle.

- Ann Hornaday, "The 34 best political movies ever made" The Washington Post Jan. 23, 2020), ranked #2

- 1976 films

- 1970s political drama films

- American films

- American political drama films

- American political thriller films

- English-language films

- Spanish-language films

- Films directed by Alan J. Pakula

- Films scored by David Shire

- Films with screenplays by William Goldman

- Biographical films about journalists

- Films about elections

- Films about freedom of expression

- Films about security and surveillance

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award-winning performance

- Cultural depictions of Richard Nixon

- Films set in offices

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films set in Miami

- Films set in 1972

- Films set in 1973

- Films set in 1974

- Films set in 1975

- Films shot in Washington, D.C.

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Procedural films

- Watergate scandal in film

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- Films about journalism

- Films about journalists

- Films about Richard Nixon

- Films about Presidents of the United States

- Films about The Washington Post

- 1970s buddy films

- 1970s political films

- American neo-noir films

- 1976 drama films

- Drama films based on actual events

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners