Dadabhai Naoroji

Dadabhai Naoroji | |

|---|---|

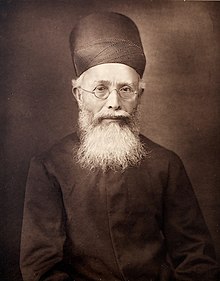

Dadabhai Naoroji c. 1889 | |

| Member of Parliament | |

| In office 1892–1895 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick Thomas Penton |

| Succeeded by | William Frederick Barton Massey-Mainwaring |

| Constituency | Finsbury Central |

| Majority | 5 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 September 1825 Navsari, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 30 June 1917 (aged 91) Bombay, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Other political affiliations | Co-founder of Indian National Congress |

| Spouse | Gulbaai |

| Residence | London, United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | University of Mumbai |

| Occupation | Academician, politician, trader |

| Signature | |

Dadabhai Naoroji (4 September 1825 – 30 June 1917) also known as the "Grand Old Man of India" and "official Ambassador of India" was an Indian Parsi scholar, trader and politician who was a Liberal Party member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom House of Commons between 1892 and 1895, and the first Asian to be a British MP,[1][2] notwithstanding the Anglo-Indian MP David Ochterlony Dyce Sombre, who was disenfranchised for corruption after nine months. Naoroji was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress.[3]

His book Poverty and Un-British Rule in India[2] brought attention to the Indian wealth drain into Britain. In it he explained his wealth drain theory. He was also a member of the Second International along with Kautsky and Plekhanov. Dadabhai Naoroji's works in the congress are praiseworthy. In 1886,1893 and 1906, i.e., thrice was he elected as the president of INC. In 2014, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg inaugurated the Dadabhai Naoroji Awards for services to UK-India relations.[4] India Post depicted Naoroji on stamps in 1963, 1997 and 2017.[5][6]

Life and career

Naoroji was born in Navsari into a Gujarati-speaking Parsi family, and educated at the Elphinstone Institute School.[7] He was patronised by the Maharaja of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad III, and started his career life as Dewan (Minister) to the Maharaja in 1874. Being an Athornan (ordained priest), Naoroji founded the Rahnumae Mazdayasne Sabha (Guides on the Mazdayasne Path) on 1 August 1851 to restore the Zoroastrian religion to its original purity and simplicity. In 1854, he also founded a Gujarati fortnightly publication, the Rast Goftar (or The Truth Teller), to clarify Zoroastrian concepts and promote Parsi social reforms.[8] In this time he also published another newspaper called "The Voice of India." In December 1855, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics and Natural Philosophy in Elphinstone College in Bombay,[9] becoming the first Indian to hold such an academic position. He travelled to London in 1855 to become a partner in Cama & Co, opening a Liverpool location for the first Indian company to be established in Britain. Within three years, he had resigned on ethical grounds. In 1859, he established his own cotton trading company, Dadabhai Naoroji & Co. Later, he became Professor of Gujarati in University College London.

In 1865, Naoroji directed and launch the London Indian Society, the purpose of which was to discuss Indian political, social and literary subjects.[10] In 1861 Naoroji founded The Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe alongside Muncherjee Hormusji Cama.[11] In 1867 he also helped to establish the East India Association, one of the predecessor organisations of the Indian National Congress with the aim of putting across the Indian point of view before the British public. The Association was instrumental in counter-acting the propaganda by the Ethnological Society of London which, in its session in 1866, had tried to prove the inferiority of the Asians to the Europeans. This Association soon won the support of eminent Englishmen and was able to exercise considerable influence in the British Parliament.[citation needed] In 1874, he became Prime Minister of Baroda and was a member of the Legislative Council of Bombay (1885–88). He was also a member of the Indian National Association founded by Sir Surendranath Banerjee from Calcutta a few years before the founding of the Indian National Congress in Bombay, with the same objectives and practices.[3] The two groups later merged into the INC, and Naoroji was elected President of the Congress in 1886. Naoroji published Poverty and un-British Rule in India in 1901.[3]

Naoroji moved to Britain once again and continued his political involvement. Elected for the Liberal Party in Finsbury Central at the 1892 general election, he was the first British Indian MP.[12][13] He refused to take the oath on the Bible as he was not a Christian, but was allowed to take the oath of office in the name of God on his copy of Khordeh Avesta. During his time he put his efforts towards improving the situation in India. He had a very clear vision and was an effective communicator. He set forth his views about the situation in India over the course of history of the governance of the country and the way in which the colonial rulers rules. In Parliament, he spoke on Irish Home Rule and the condition of the Indian people. He was also a notable Freemason. In his political campaign and duties as an MP, he was assisted by Muhammed Ali Jinnah, the future Muslim nationalist and founder of Pakistan. In 1906, Naoroji was again elected president of the Indian National Congress. Naoroji was a staunch moderate within the Congress, during the phase when opinion in the party was split between the moderates and extremists. Naoroji was a mentor to Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. He was married to Gulbai at the age of eleven. He died in Bombay on 30 June 1917, at the age of 91. Today the Dadabhai Naoroji Road, a heritage road of Mumbai, is named after him. Also, the Dadabhai Naoroji Road in Karachi, Pakistan is also named after him as well, as Naoroji Street in the Finsbury area of London. A prominent residential colony for central government servants in the south of Delhi is also named Naoroji Nagar. His granddaughters Perin and Khrushedben were also involved in the freedom struggle. In 1930, Khurshedben was arrested along with other revolutionaries for attempting to hoist the Indian flag in a Government College in Ahmedabad.[14]

Naoroji's drain theory and poverty

Dadabhai Naoroji's work focused on the drain of wealth from India to England during colonial rule of British in India.[15] One of the reasons that the Drain theory is attributed to Naoroji is his decision to estimate the net national profit of India, and by extension, the effect that colonisation has on the country. Through his work with economics, Naoroji sought to prove that Britain was draining money out of India.[16] Naoroji described 6 factors which resulted in the external drain. Firstly, India is governed by a foreign government. Secondly, India does not attract immigrants which bring labour and capital for economic growth. Thirdly, India pays for Britain's civil administrations and occupational army. Fourthly, India bears the burden of empire building in and out of its borders. Fifthly, opening the country to free trade was actually a way to exploit India by offering highly paid jobs to foreign personnel. Lastly, the principal income-earners would buy outside of India or leave with the money as they were mostly foreign personnel.[17] In Naoroji's book 'Poverty' he estimated a 200–300 million pounds loss of India's revenue to Britain that is not returned. Naoroji described this as vampirism, with money being a metaphor for blood, which humanised India and attempted to show Britain's actions as monstrous in an attempt to garner sympathy for the nationalist movement.[18]

When referring to the Drain, Naoroji stated that he believed some tribute was necessary as payment for the services that England brought to India such as the railways. However the money from these services were being drained out of India; for instance the money being earned by the railways did not belong to India, which supported his assessment that India was giving too much to Britain. India was paying tribute for something that was not bringing profit to the country directly. Instead of paying off foreign investment which other countries did, India was paying for services rendered despite the operation of the railway being already profitable for Britain. This type of drain was experienced in different ways as well, for instance, British workers earning wages that were not equal with the work that they have done in India, or trade that undervalued India's goods and overvalued outside goods.[15][17] Englishmen were encouraged to take on high paying jobs in India, and the British government allowed them to take a portion of their income back to Britain. Furthermore, the East India Company was purchasing Indian goods with money drained from India to export to Britain, which was a way that the opening up of free trade allowed India to be exploited.[19]

When elected to Parliament by a narrow margin of 5 votes his first speech was about questioning Britain's role in India. Naoroji explained that Indians were either British subjects or British slaves, depending on how willing Britain was to give India the institutions that Britain already operated. By giving these institutions to India it would allow India to govern itself and as a result the revenue would stay in India.[20] It is because Naoroji identified himself as an Imperial citizen that he was able to address the economic hardships facing India to an English audience. By presenting himself as an Imperial citizen he was able to use rhetoric to show the benefit to Britain that an ease of financial burden on India would have. He argued that by allowing the money earned in India to stay in India, tributes would be willingly and easily paid without fear of poverty; he argued that this could be done by giving equal employment opportunities to Indian professionals who consistently took jobs they were over-qualified for. Indian labour would be more likely to spend their income within India preventing one aspect of the drain.[18] Naoroji believed that to solve the problem of the drain it was important to allow India to develop industries; this would not be possible without the revenue draining from India into England.

It was also important to examine British and Indian trade to prevent the end of budding industries due to unfair valuing of goods and services.[19] By allowing industry to grow in India, tribute could be paid to Britain in the form of taxation and the increase in interest for British goods in India. Over time, Naoroji became more extreme in his comments as he began to lose patience with Britain. This was shown in his comments which became increasingly aggressive. Naoroji showed how the ideologies of Britain conflicted when asking them if they would allow French youth to occupy all the lucrative posts in England. He also brought up the way that Britain objected to the drain of wealth to the papacy during the 16th century.[21] Naoroji's work on the drain theory was the main reason behind the creation of the Royal Commission on Indian Expenditure in 1896 in which he was also a member. This commission reviewed financial burdens on India and in some cases came to the conclusion that those burdens were misplaced.[22]

Views and legacy

Dadabhai Naoroji is regarded as one of the most important Indians during the independence movement. In his writings, he considered that the foreign intervention into India was clearly not favourable for the country.

Further development was checked by the frequent invasions of India by, and the subsequent continuous rule of, foreigners of entirely different character and genius, who, not having any sympathy with the indigenous literature – on the contrary, having much fanatical antipathy to the religion of the Hindus – prevented its further growth. Priest-hood, first for power and afterwards from ignorance, completed the mischief, as has happened in all other countries.[23]

Naoroji is remembered as the "Grand Old Man of Indian Nationalism"

Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Naoroji in a letter of 1894 that "The Indians look up to you as children to the father. Such is really the feeling here."[24]

Bal Gangadhar Tilak admired him; he said:

If we twenty eight crore of Indians were entitled to send only one member to the British parliament, there is no doubt that we would have elected Dadabhai Naoroji unanimously to grace that post.[25]

Here are the significant extracts taken from his speech delivered before the East India Association on 2 May 1867 regarding what educated Indians expect from their British rulers.

The difficulties thrown in the way of according to the natives such reasonable share and voice in the administration of the country ad they are able to take, are creating some uneasiness and distrust. The universities are sending out hundreds and will soon begin to send out thousands of educated natives. This body naturally increases in influence...

"In this Memorandum I desire to submit for the kind and generous consideration of His Lordship the Secretary of State for India, that from the same cause of the deplorable drain [of economic wealth from India to England], besides the material exhaustion of India, the moral loss to her is no less sad and lamentable . . . All [the Europeans] effectually do is to eat the substance of India, material and moral, while living there, and when they go, they carry away all they have acquired . . . The thousands [of Indians] that are being sent out by the universities every year find themselves in a most anomalous position. There is no place for them in their motherland . . . What must be the inevitable consequence? . . . despotism and destruction . . . or destroying hand and power. "

In this above quotation he explains his theory in which the British used India as a drain of wealth.

A plaque referring to Dadabhai Naoroji is located outside the Finsbury Town Hall on Rosebery Avenue, London.

Works

- Started the Rast Goftar Anglo-Gujarati Newspaper in 1854.

- The manners and customs of the Parsees (Bombay, 1864)

- The European and Asiatic races (London, 1866)

- Admission of educated natives into the Indian Civil Service (London, 1868)

- The wants and means of India (London, 1876)

- Condition of India (Madras, 1882)

- Poverty of India

- A Paper Read Before the Bombay Branch of the East India Association, Bombay, Ranima Union Press, (1876)

- C. L. Parekh, ed., Essays, Speeches, Addresses and Writings of the Honourable Dadabhai Naoroji, Bombay, Caxton Printing Works (1887). An excerpt, "The Benefits of British Rule", in a modernised text by J. S. Arkenberg, ed., on line at Paul Halsall, ed., Internet Modern History Sourcebook.

- Lord Salisbury's Blackman (Lucknow, 1889)

- Naoroji, Dadabhai (1861). The Parsee Religion. University of London.

- Dadabhai Naoroji (1902). Poverty and Un-British Rule in India. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

poverty and un british rule in india.

; Commonwealth Publishers, 1988. ISBN 81-900066-2-2

He made the first attempt to estimate the national income of India in 1867.

See also

References

- ^ Mukherjee, Sumita. "'Narrow-majority' and 'Bow-and-agree': Public Attitudes Towards the Elections of the First Asian MPs in Britain, Dadabhai Naoroji and Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree, 1885–1906" (PDF). Journal of the Oxford University History Society (2 (Michaelmas 2004)).

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 167.

- ^ a b c Nanda, B. R. (2015) [1977], Gokhale: The Indian Moderates and the British Raj, Legacy Series, Princeton University Press, p. 58, ISBN 978-1-4008-7049-3

- ^ "Dadabhai Naoroji Awards presented for the first time – GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "India Post Honors Dadabhai Naoroji With Stamp – Parsi Times". Parsi Times. 6 January 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ "India Post Issued Stamp on Dadabhai Naoroji". Phila-Mirror. 29 December 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ Dilip Hiro (2015). The Longest August: The Unflinching Rivalry Between India and Pakistan. Nation Books. p. 9. ISBN 9781568585031. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Mohanram, edited by Ralph J. Crane & Radhika (2000). Shifting continents/colliding cultures : diaspora writing of the Indian subcontinent. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 62. ISBN 978-9042012615. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ Mistry, Sanjay (2007) "Naorojiin, Dadabhai" in Dabydeen, David et al. eds. The Oxford Companion of Black British History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 336–7. ISBN 9780199238941

- ^ Fourteenth Annual General Meeting of the British Indian Association, 14 February 1866, p.22 British Indian Association

- ^ John R. Hinnells (28 April 2005). The Zoroastrian Diaspora: Religion and Migration. OUP Oxford. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-19-826759-1. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Peters, K. J. (29 May 1946). "Indian Patchwork Is Made of Many Colours". Aberdeen Journal. Retrieved 2 December 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.(subscription required)

- ^ "From the archive, 26 July 1892: Britain's first Asian MP elected", The Guardian, 26 July 2013, retrieved 2 May 2018

- ^ "Millionaire's daughter arrested". Portsmouth Evening News. 21 August 1930. Retrieved 2 December 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive.(subscription required)

- ^ a b Kozicki, Richard P.; Ganguli, B. N. (1967). "Reviewed work: Dadabhai Naoroji and the Drain Theory., B. N. Ganguli". The Journal of Asian Studies. 26 (4): 728–729. doi:10.2307/2051282. JSTOR 2051282.

- ^ Raychaudhuri G.S. (1966). "On Some Estimates of National Income Indian Economy 1858–1947". Economic and Political Weekly. 1 (16): 673–679. JSTOR 4357298.

- ^ a b Ganguli B.N. (1965). "Dadabhai Naoroji and the Mechanism of 'External Drain'". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 2 (2): 85–102. doi:10.1177/001946466400200201.

- ^ a b Banerjee, Sukanya (2010) Becoming Imperial Citizens : Indians in the Late Victorian Empire Durham. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4608-1

- ^ a b Doctor, Adi H. (1997) Political Thinkers of Modern India. New Delhi Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-8170996613

- ^ Chatterjee, Partha (1999). "Modernity, Democracy and a Political Negotiation of Death". South Asia Research. 19 (2): 103–119. doi:10.1177/026272809901900201.

- ^ Chandra, Bipan (1965). "Indian Nationalists and the Drain, 1880—1905". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 2 (2): 103–144. doi:10.1177/001946466400200202.

- ^ Chishti, M. Anees ed. (2001) Committees And Commissions in Pre-Independence India 1836–1947 Volume 2: 1882–1895. New Delhi Mittal Publications. ISBN 9788170998020

- ^ "Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London", p. 9

- ^ Bakshi, Shiri Ram (1988) Gandhi and Indians in South Africa. p. 37.

- ^ Pasricha, Ashu (1998) Encyclopedia Eminent Thinkers. Vol. 11: The Political Thought of Dadabhai Naoroji. Concept Publishing Company. p. 30. ISBN 9788180694912

Further reading

- Rustom P. Masani, Dadabhai Naoroji (1939).

- Munni Rawal, Dadabhai Naoroji, Prophet of Indian Nationalism, 1855–1900, New Delhi, Anmol Publications (1989).

- S. R. Bakshi, Dadabhai Naoroji: The Grand Old Man, Anmol Publications (1991). ISBN 81-7041-426-1

- Verinder Grover, ‘'Dadabhai Naoroji: A Biography of His Vision and Ideas’’ New Delhi, Deep & Deep Publishers (1998) ISBN 81-7629-011-4

- Debendra Kumar Das, ed., ‘'Great Indian Economists : Their Creative Vision for Socio-Economic Development.’’ Vol. I: ‘Dadabhai Naoroji (1825–1917) : Life Sketch and Contribution to Indian Economy.’’ New Delhi, Deep and Deep (2004). ISBN 81-7629-315-6

- P. D. Hajela, ‘'Economic Thoughts of Dadabhai Naoroji,’’ New Delhi, Deep & Deep (2001). ISBN 81-7629-337-7

- Pash Nandhra, entry Dadabhai Naoroji in Brack et al. (eds).Dictionary of Liberal History; Politico's, 1998

- Zerbanoo Gifford, Dadabhai Naoroji: Britain's First Asian MP; Mantra Books, 1992

- Codell, J. "Decentering & Doubling Imperial Discourse in the British Press: D. Naoroji & M. M. Bhownaggree," Media History 15 (Fall 2009), 371–84.

- Metcalf and Metcalf, Concise History of India

External links

- Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs

- "Dr Dadabhai Naoroji, 'The Grand Old Man of India'", Vohuman.org – Presents a complete chronology of Naoroji's life.

- Portraits of Dadabhai Naoroji at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Works by or about Dadabhai Naoroji at the Internet Archive

- Works by Dadabhai Naoroji at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- B. Shantanu, "Drain of Wealth during British Raj", iVarta.com, 6 February 2006

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Dadabhai Naoroji

- India House

- 1825 births

- 1917 deaths

- Parsi people

- Parsi people from Mumbai

- British Zoroastrians

- Businesspeople from Mumbai

- British politicians of Indian descent

- British people of Parsi descent

- Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

- UK MPs 1892–1895

- Presidents of the Indian National Congress

- Indian emigrants to England

- English people of Parsi descent

- English people of Indian descent

- Elphinstone College alumni

- Academics of University College London

- Politicians from Mumbai

- 19th-century Indian politicians

- Indian National Congress politicians from Maharashtra

- Zoroastrian studies scholars