History of Saturday Night Live

The long-running American late-night sketch comedy show Saturday Night Live (SNL) first premiered on NBC on October 11, 1975, and its fiftieth and most recent season premiered on September 28, 2024. Created by Lorne Michaels, who is the original and current showrunner, its history has been shaped by its large and constantly-changing cast of performers, as well as changes in its writing staff from year to year. It has played a prominent role in American popular culture and television since its inception, and changing attitudes towards cultural diversity have been evident particularly in its recent history.

Initially called NBC's Saturday Night and envisioned as something closer to a traditional variety show, the program was developed as a replacement for reruns of The Tonight Show and quickly became a staple of late-night television. The early years of SNL were dominated by its initial cast of performers, which became known as the "Not Ready for Prime Time Players", and included such performers as Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, and Gilda Radner. The cast members soon became famous during the first season, and the show became immediately known for its mix of satirical humor, political commentary, and celebrity impersonations, quickly developing a cult following.

Michaels left the program in 1980; the program was executive produced by associate producer Jean Doumanian for a year, then Dick Ebersol for several years, before Michaels returned in 1985. After an unstable 1985–1986 season, he introduced a new cast featuring performers like Phil Hartman and Dana Carvey, stabilising the show's production and helping to restore its popularity. He also reintroduced political satire of figures such as George H.W. Bush, an element of the series that had been deprioritised during the Ebersol era. Subsequent decades saw the rise of cast members like Will Ferrell, Tina Fey, and Kate McKinnon, helping to keep the show relevant to new generations of viewers.

Throughout its history, SNL has experienced fluctuations in critical reception and ratings. The show has launched the careers of numerous comedians and actors, with many cast members going on to successful careers in film and television. As of its fiftieth season in 2024, Saturday Night Live is one of the longest-running programs in television history, and has produced over 970 episodes. It has won numerous awards, including multiple Primetime Emmy Awards, and is often cited for its influence on popular culture and its impact on political satire.

Development: 1974–1975

[edit]

Beginning in 1965, NBC network affiliates broadcast reruns of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson on Saturday or Sunday nights. In 1974, Johnny Carson petitioned to NBC executives for the weekend shows to be pulled and saved so they could be aired during weeknights, allowing him to take time off.[1][2] In response, NBC president Herbert Schlosser approached the vice president of late-night programming, Dick Ebersol, and asked him to create a show to fill the Saturday night time slot.[3] The network had a weak Saturday night lineup at the time that garnered poor ratings,[4] and networks had little interest in late-night Saturday shows until the mid-1970s.[2]

At the suggestion of Paramount Pictures executive Barry Diller, Schlosser and Ebersol then approached Lorne Michaels. Over the next three weeks, Ebersol and Michaels developed the latter's idea for a variety show featuring high-concept comedy sketches, political satire, and music performances that would attract 18- to 34-year-old viewers.[5][6] NBC decided to base the new show at their studios in 30 Rockefeller Center. Michaels was given Studio 8H, a converted radio studio that was home to NBC's election and Apollo moon landing coverage. It was revamped for the premiere at a cost of $250,000.[7] By 1975, Michaels had assembled the show's initial cast, including Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Jane Curtin, Garrett Morris, Laraine Newman, Gilda Radner, and George Coe.[8] The cast was nicknamed the "Not Ready For Prime-Time Players",[9][10] a term coined by show writer Herb Sargent.[11] Much of the talent pool involved in the inaugural season was recruited from The National Lampoon Radio Hour,[12][13] including the original head writer, Michael O'Donoghue.[14]

Radner was the first person hired after Michaels himself.[15] Chase was initially hired as a writer but then became a performer.[16] Newman was brought aboard after having already worked with Michaels on a Lily Tomlin special in 1974.[15] Morris was initially brought in as a writer, but attempts to have him fired by another writer led Michaels to have Morris audition for the cast, where he turned in a successful performance.[15] Curtin and Belushi were the last two cast members hired.[15] Belushi had a disdain for television and had repeatedly turned down offers to appear on other shows, but decided to work with the show because of the involvement of Radner and writers Anne Beatts and O'Donoghue.[15] Michaels was still reluctant to hire Belushi, believing he would be a source of trouble for the show, but Beatts, O'Donoghue, and Ebersol successfully argued for his inclusion.[15] NBC executives insisted that Coe join the cast to balance out Michaels's younger selections.[17]

The original theme music was written by Howard Shore, who was the original bandleader.[18] The show was originally conceived with three rotating permanent hosts: Lily Tomlin, Richard Pryor, and George Carlin. According to Ebersol, consideration was given to Steve Martin and singer Linda Ronstadt also being included as a duo.[19] When Pryor dropped out because his brand of comedy was not censor-friendly, the concept was dropped.[20]

Debut and early years: 1975–1980

[edit]First seasons and cult success

[edit]NBC's Saturday Night[note 1] debuted on October 11, 1975,[6] with an episode featuring Carlin as host.[23] The cast was initially paid $750 per episode, and essentially lived at the offices, according to Michaels.[24][21] Chase was the first performer to say the show's introduction line in the first episode,[21] and would say it in all but two episodes for the rest of the season.[25] Michaels said it would take a few weeks for the show to find itself on-air.[26] Early episodes were more experimental with the show's format; segments from The Muppets were frequently featured in the first season, and the second episode featured eleven musical performances from host Paul Simon, with minimal appearances by the cast, who only appeared as the Bees only to be informed by Simon that their segment had been cut and Chase in the opening and Weekend Update.[21] The fourth episode, hosted by Candice Bergen, was seen as a turning point, with the cast featuring in most segments. The cast and crew were particularly happy with a "Jaws II" sketch, which was longer than was typical and featured multiple sets. Each cast member handed Bergen a red rose during the goodnights, and the show's format became more established following this episode.[27]

The seventh episode hosted by Richard Pryor was an important one for Michaels, who had insisted on booking Pryor as host, feeling that he could aid in making the show more modern.[28] However, network officials were concerned about Pryor's content and the possibility of profanity,[29] and ordered Michaels to run the episode on a five-second tape delay.[30] He was initially disallowed as host entirely, until Michaels threatened to walk off the show in protest.[31] Pryor, as the first person of color to host the show, found the delay to be an insult when informed after the broadcast, and objected to being treated differently to other comedians.[31][note 2] The Pryor episode was considered one of the show's best episodes, according to authors Doug Hill and Josh Weingrad.[33] The episode's "Word Association" sketch, featuring Pryor and Chase, is considered one of the greatest SNL sketches of all time, according to Rolling Stone.[34][35]

SNL's humor soon began to be seen as refreshing and daring, in comparison to previous sketch and variety shows that would rarely deal with controversial topics and issues,[36] and the show soon developed a cult following.[37][6] Michaels resisted the network censors on many occasions, and learned to effectively exploit the network's appeals process in order to maintain creative control and keep controversial sketches in production.[38] The cast's improvisational backgrounds allowed them to experiment with different forms of comedy.[10] Iconic characters during this period of the show included Belushi's samurai, the Coneheads (Aykroyd, Curtin, Newman), and Radner's Roseanne Roseannadanna.[39]

Some NBC executives were not satisfied with the show's Nielsen ratings.[37] Michaels and Ebersol successfully argued that baby boomers constituted a majority of the show's viewers according to Nielsen metrics, and many of them watched little else on television.[40] Young adults were the most desirable demographic for advertisers,[41] and executives eventually decided to keep the show on the air despite angry letters and phone calls from viewers who were offended by certain sketches.[42]

Chase was the first anchor of the show's recurring "Weekend Update" segment, and therefore received more screen time than the rest of the cast. Physical comedy and exaggerated pratfalls became his trademarks, and he became the show's first breakout star. His impression of Gerald Ford during the 1976 presidential campaign was later cited as a factor in Ford losing the November 2, 1976 election.[25][43] Chase's success led to tensions with the rest of the cast, particularly Belushi. Network executives also wanted him for a potential prime-time show, and he soon left the show during the 1976–1977 season.[44][note 3] He was replaced by Bill Murray, whom Michaels had intended to hire for the initial cast but was unable to because of budget restrictions.[45] Murray had a shaky start, but by the end of the second season, had begun to develop a following, with a sleazy know-it-all persona and characters such as Nick the Lounge Singer that became popular with viewers.[46] The show became a mainstream hit by 1978, and spawned "Best of Saturday Night Live" compilations that also reached viewers who could not stay awake for the live broadcasts.[47]

Cast tensions

[edit]Chase returned to host in 1978; during the live telecast, Murray, goaded by Belushi, got into a physical altercation with Chase while musical guest Billy Joel was performing, according to Newman and Michaels in 2002.[48] Chase later said the incident actually happened right before he delivered the opening monologue.[49] Chase's departure to work in movies had made Michaels possessive of his talent; he threatened to fire Aykroyd if he accepted the role of D-Day in the 1978 comedy Animal House (which Belushi starred in), and later refused to allow SNL musician/performer Paul Shaffer to participate in The Blues Brothers with Aykroyd and Belushi.[50][51] Animal House was a major box office success in 1978, which led to a further spike in SNL's popularity.[12] Belushi's independent success began to cause jealousy and discontent in the other cast members,[52] and Michaels became concerned that some cast members considered the show primarily a launching pad for movies and popular music.[53]

"It was embarrassing. We were the TV literati, very hip, the darlings of some intellectual culture. Then it sort of degenerated into people who thought the more shrill the better. Fan mail started to be from fourteen-year-olds who couldn't spell."

Radner starred in a successful one-woman Broadway show titled Gilda Live in the fall of 1979, produced by Michaels.[55] Tensions developed between Radner and some SNL writers because she and Michaels had spent much of the year working on the project.[56] She had also recently broken off a relationship with Murray, and the two could barely speak to one another.[57] Her Broadway show was filmed by director Mike Nichols for release to cinemas, but the project was a critical and financial disappointment upon its release in March 1980, despite the success of the Broadway show itself.[58] The stress of these projects caused "exhaustion" for Radner during SNL's 1979–1980 season, according to SNL historians Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad.[59]

Murray's visibility increased during this period, as cinemas screened the popular comedy Meatballs, which launched his movie career. Its PG rating allowed popularity with a broader audience, and this resulted in new SNL viewers who were not familiar with what writer Rosie Shuster considered to be the unorthodox style of the first two seasons.[60] The rapidly changing viewer demographics caused further concern for Michaels about the possible departures of cast members and writers.[61]

Drugs were a major problem during the show's first five years. Cocaine had become an "integral part of the working progress" on SNL by the 1978–1979 season, according to Hill and Weingrad.[62] Newman had developed serious eating disorders as well as drug problems, and spent so much time in her dressing room playing solitaire that for Christmas 1979, castmate Radner gave her a deck of playing cards with a picture of Laraine on the face of each card.[63] Radner was also suffering from bulimia.[62][64] Morris felt underutilized by the writers, and was often assigned sketches that involved racial stereotypes. One of these was a planned "Tarbrush" sketch that would dull African-Americans' supposedly shiny teeth, which was pulled at the last minute by Michaels.[65] He began to freebase cocaine, and during rehearsals for an episode hosted by Kirk Douglas, ran screaming onto the set, saying that someone had put an "invisible hypnotist robot" on his shoulder who watched him everywhere he went.[66] During the 1979–1980 season, Michaels had a guard posted outside the elevators on the seventeenth floor. Officially, he was there to keep away fans, but most on the show believed it was to protect against potential sweeps by law enforcement.[62]

Michaels and cast departures

[edit]Aykroyd and Belushi left the show after the 1978–1979 season to make The Blues Brothers.[67] Murray felt that Aykroyd and Belushi had left him stranded, and essentially forced him and Morris to play too many of the male parts in sketches.[57] The following season saw the hiring of many writers as featured players, such as Al Franken, Tom Davis, and Harry Shearer.[68] (Though Franken and Davis were technically featured cast members since season 3;[69] while Shearer was promoted to Repertory Status midway through the season) Another prominent contributor was writer Don Novello, whose "Father Guido Sarducci" character was especially popular and appeared on Weekend Update repeatedly during the season.[70]

As the fifth season ended in 1980, Michaels, emotionally and physically exhausted, asked executives to place the show on hiatus for a year in order to allow him time to pursue other projects.[71] Concerned that the show would be cancelled without him, Michaels suggested Franken, Davis, and Jim Downey as his replacements. NBC president Fred Silverman disliked Franken and was infuriated by his Update routine on May 10, 1980, called "A Limo for a Lame-O", a critique of Silverman's job performance and his insistence on traveling by limousine at the network's expense. Silverman blamed Michaels for approving this Weekend Update segment.[72] Unable to secure the deal that he wanted, Michaels chose to leave NBC for Paramount Pictures, intending to bring associate producer Jean Doumanian along with him. Michaels later learned that Doumanian had been given his position at SNL after being recommended by her friend, NBC Vice President Barbara Gallagher.[73]

The remaining cast appeared together for the last time on May 24, 1980, the final episode of the season, hosted by long-time host Buck Henry, who never again returned to host. Almost every writer and cast member, including Michaels, left the show after this episode.[74] Brian Doyle-Murray was the only writer to stay on for the following season with Doumanian as producer.[75]

Jean Doumanian and Dick Ebersol years: 1980–1985

[edit]Jean Doumanian season

[edit]The reputation of the show as a springboard to fame meant that many aspiring stars were eager to join the new series. Doumanian was tasked with hiring a full cast and writing staff in less than three months, and NBC immediately cut the show's budget from the previous $1 million per episode down to just $350,000. Doumanian also faced resentment and sabotage from the remaining Michaels staff.[76] Cast member Harry Shearer, who disliked Michaels, informed Doumanian that he would stay as long as she let him completely overhaul the program. Doumanian refused, so Shearer also left.[77]

The Doumanian-era cast faced immediate comparisons to the beloved former cast and was not received favorably by critics. Ratings were significantly down for the new season, and audiences failed to connect to the original cast's replacements, such as Charles Rocket and Ann Risley.[78] The New York Times wrote that "only the shell remained" of the previous show, and that the new season lacked innovation.[79] Tom Shales wrote that the show was a "snide and sordid embarrassment".[80]

In a February 1981 episode hosted by Charlene Tilton, Rocket used the profanity "fuck" during a sketch.[81] Director Dave Wilson, upon hearing the word, reportedly threw his script down and left the control room, and the incident was cut from the subsequent West Coast broadcast. Rocket later said he was trying to kill time before the show's close and had not meant to utter the word.[82][83] Following this episode, Doumanian was dismissed after only ten months on the job.[84][85]

Dick Ebersol years

[edit]

Although some executives suggested SNL be cancelled, Brandon Tartikoff, who succeeded Silverman as network chief in mid-1981, believed the show's concept was more important than its financial performance and decided to keep it on the air. He turned to Dick Ebersol to take over as producer, who sought Michaels' approval in order to avoid the same staff sabotage that had plagued Jean Doumanian's tenure.[86] To reconnect with the Michaels era, Ebersol re-hired Michael O'Donoghue as head writer[87] and fired most of Doumanian's hires, keeping only Eddie Murphy and Joe Piscopo.[88] He initially pursued John Candy and Catherine O'Hara from SCTV for the new cast. While Candy declined, O'Hara accepted, before changing her mind after a heated production meeting where O'Donoghue berated the cast and writers.[89] O'Donoghue himself was soon fired after creating chaos on set and proposing radical changes, including attempting to fire announcer Don Pardo live on air.[90]

Ebersol's first episode aired on April 11, featuring Chevy Chase on Weekend Update and an Al Franken commentary that humorously suggested it was time to "put SNL to sleep". Seeking to remind viewers of the original era, Ebersol allowed Franken's mock-serious segment to air.[91] However, Ebersol's approach differed markedly from Michaels'. His sketches leaned towards more accessible, broad comedy, which alienated some long-time fans, writers, and cast members. Tim Kazurinsky described Ebersol's style as favoring "lowest common denominator" content.[92][93] Ebersol focused on appealing to younger viewers, and discouraged sketches longer than five minutes in order to maintain their attention.[93] His distaste for political humor led the show to largely avoid jokes about President Ronald Reagan during his time as showrunner.[94]

Coming from a management background, Ebersol was adept at maintaining network relationships and took on many business and production duties,[95] increasingly leaving producer Bob Tischler in charge of creative decisions.[96] Under Ebersol's leadership, Eddie Murphy, who had been underused during Doumanian's tenure,[97][note 4] rose to prominence with popular characters like Mister Robinson's Neighborhood and Gumby.[99] His success was a major factor in the show's resurgence,[100] though it created tensions within the cast, particularly after Ebersol allowed Murphy to host following the cancellation of Murphy's 48 Hrs. co-star, Nick Nolte.[101][note 5]

After Murphy and much of the cast left following the 1983–1984 season, the show appeared talent-deprived. In a break with tradition, the producers hired established comedians like Billy Crystal and Martin Short for the 1984–1985 season, bringing their well-known material to the show.[102] Crystal had nearly appeared in SNL's first episode in 1975 but left due to a dispute during rehearsals.[103] During this season, he introduced popular characters such as Fernando.[104] However, the high salaries for Crystal and Short, $25,000 and $20,000 per episode respectively, drove up production costs.[102] Though this season was considered one of the series' funniest, it diverged significantly from Michaels' innovative approach in the eyes of audiences.[105][106]

By the end of the season, several cast members had grown weary of the demanding production schedule and were reluctant to return, leaving Crystal as the sole established cast member willing to continue. Like Michaels before him, Ebersol informed NBC that he would only return if the show took a hiatus to recast and rebuild.[107] He also proposed significantly departing from the established live format.[108] NBC rejected these requests and instead decided to approach Michaels to return as producer.[107]

Michaels returns: 1985–1995

[edit]1985–1986 season

[edit]Following unsuccessful forays into film and television, in need of money, and eager not to see Tartikoff cancel the show, Michaels decided to return for the 1985–1986 season. The show was again recast, with Michaels borrowing Ebersol's idea to seek out established actors such as Randy Quaid and Anthony Michael Hall, as well as younger stars like Robert Downey Jr. and Joan Cusack.[71] Michaels also expressed a desire to let a new generation "create it in its own image", seeking to appeal to a younger target audience.[109]

Writers found it difficult to write sketches for the eclectic new cast, which was reportedly put together in just six weeks.[110] The season premiere, hosted by Madonna, received "scathing" reviews according to The New York Times;[109] writer Downey later said the episode was one of the worst in the show's history.[111] Head writer Franken was later critical of Michaels' decision to seek a younger cast, observing that it was "impossible to write a Senate hearing", and Ebersol later called the year "very dark".[110] The season overall is considered one of the show's worst.[112] In April 1986, Tartikoff again made the decision to cancel the show, until he was convinced by producer Bernie Brillstein to give it one more year.[113]

1986–1990 cast

[edit]

The show was renewed for the 1986–1987 season, but, for the first time in its history, for only thirteen episodes instead of the usual twenty-two.[114] Michaels again fired most of the cast, and unlike the previous seasons, sought out unknown talent such as Dana Carvey and Phil Hartman instead of known names.[115] Only a few cast members from the previous season were retained, such as Jon Lovitz, Nora Dunn, and Dennis Miller, whose hosting of Weekend Update had been a source of praise.[116] The October 11 premiere hosted by Sigourney Weaver opened with Madonna reading a mock NBC statement that the previous season had been "a dream... a horrible, horrible dream".[117]

This new cast was successful at reviving the show's popularity in the eyes of critics and audiences.[118] The Washington Post observed that the show had "new life", crediting Carvey in particular.[119] It was considered a more disciplined, straight cast than previous eras, with less alcohol and drug use.[120] Lovitz was known for playing sleazy, obnoxious characters such as Tommy Flanagan, a pathological liar, and Carvey's impressions of celebrities like John Travolta quickly proved popular. He also created popular new characters such as Church Lady and the Grumpy Old Man.[121] The Church Lady's mannerisms was inspired by NBC's increased censorship of the show compared to the initial years, which Carvey and Dunn criticised.[120] Michaels had also reintroduced political humor to the show, and Carvey's impression of George H.W. Bush is considered one of the best presidential impressions in the show's history.[122]

The new core group of eight would be unchanged for the next four years,[123] excluding the addition of Mike Myers in 1989.[124] A two-and-a-half-hour prime time special aired on September 24, 1989, to celebrate the series' fifteenth year on the air. Original cast members Chase, Aykroyd, Curtin, Morris, and Newman all returned along with other cast and crew, with tributes to the late Belushi and Radner. Michaels said he and Tartikoff wanted to bring the "old" and "new" casts together to celebrate.[125]

Controversial comedian Andrew Dice Clay hosted the show on May 12, 1990, which prompted cast member Dunn to boycott the episode that week. Her actions were perceived as a publicity stunt by some involved with the show's production. After the cast took a vote, Dunn was not invited back to the cast for the following season.[126]

"Bad Boys" era: 1990–1995

[edit]

In the early 1990s, much of this core cast began to leave the show, and younger performers such as Chris Farley and Adam Sandler began to be promoted to repertory status. Carvey later remarked that these cast members were "bursting with energy" and that it was a natural time to transition to a newer cast.[127] Nealon observed that the newer cast members were much younger than him, almost as if they were his "teenage sons".[128]

Of the new cast members, Farley often used his size and physicality in sketches, like in the "Chippendales Audition" sketch alongside Patrick Swayze,[129] while David Spade's dry attitude and comedy quickly caught on with audiences.[130] Some of these cast members, like Sandler, Farley, Rob Schneider, Spade, and Chris Rock, would come to be known as the "Bad Boys of SNL" for their outrageous comedy style.[129][131] Many of these performers remained fairly close in the years after they left the show, often appearing in each other's movies.[129] Many of the sketches written by this newer cast mocked authority; some critics described it as "frat boy" humor, filled with profane language and jokes about bodily functions.[127] Afraid of cast members leaving for film careers, Michaels had overcrowded the cast, causing a divide between the veteran members and the new, younger talent. This led to increased competition for the show's limited screen time, and an increasing reliance on "younger", less subtle humor.[132]

An epynomous film based on Carvey and Myer's "Wayne's World" sketch was released on February 14, 1992, and was a critical and commercial success.[133][134] It was the only SNL film to gross over $100 million at the box office.[135] The film's success led to increased ratings for the show, which shed more light on what head writer Downey and many others thought were significant writing issues at the show.[136] The show also received much attention for a highly-publicised incident in October 1992 when musical guest Sinéad O'Connor presented a photo of Pope John Paul II while singing the word "evil", before tearing the image into pieces and saying "Fight the real enemy!"[137][138] NBC had no foreknowledge of O'Connor's plan; and she was banned for life from the network;[139] the show received thousands of calls in the aftermath of the incident, and protests against O'Connor occurred outside of 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[137]

The show lost Carvey and Hartman, two of its biggest stars, between 1992 and 1994. Hartman later gave an interview to TV Guide criticising the show's writing during this period, saying he felt like he had gotten off the Titanic.[140] Chris Rock left the show in 1993 after three years as a cast member, later criticising the show for limiting him to stereotypically Black roles.[141] Wanting to increase SNL's ratings and profitability, NBC West Coast president Don Ohlmeyer and other executives began to actively interfere in the show, recommending that new stars such as Chris Farley and Adam Sandler be fired and critiquing the costly nature of performing the show live. The show faced increasing criticism from the press and cast, in part encouraged by the NBC executives hoping to weaken Michaels's position.[142]

These issues had reached their peak by the 1994–1995 season, which is considered one of the series' worst. A widely-publicised profile of the show in New York during this period was highly critical of the show's humor, cast, and backstage dysfunction.[143][144] Nathan Rabin of The A.V. Club later called the season "brutally unfunny", criticising perceived homophobic sketches and the cast's lack of diversity.[145] Michaels received a lucrative offer to develop a Saturday night project for CBS during this time, but remained loyal to SNL.[146]

Cast overhaul: 1995–2005

[edit]

With the show being near cancellation, Michaels decided to overhaul the show for the 1995–1996 season. The only holdovers from the previous season were Norm Macdonald, Mark McKinney, Tim Meadows, Molly Shannon and Spade.[147] Michaels added a number of performers that would become important to the show, including Will Ferrell, Cheri Oteri, and Darrell Hammond.[148] The smaller cast also allowed producers to reduce the show's budget, which had reached a reported $1.5 million a week in the previous season.[149] Lenny Pickett also took over for G.E. Smith as leader of the Saturday Night Live Band,[150] and Jim Downey was removed as head writer.[151]

Of the cast members held over from the previous season, only Meadows and Spade were actual veterans. The other three were still newcomers to the show. Macdonald had a few bit parts in his first year (the 1993–1994 season) and had taken over from Nealon as the anchor of Weekend Update during the 1994–1995 season, his performance considered a high point that year.[152][153] Al Franken and Bill Maher also auditioned for the role.[154] Macdonald quickly became known for making frequent jokes about the criminal trial of O.J. Simpson, who was accused of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown. After Simpson's controversial acquittal in October 1995, Macdonald opened the segment with the joke, "Well, it is finally official. Murder is legal in the state of California."[154]

Don Ohlmeyer, a network executive that oversaw Michaels and SNL, was a longtime friend of Simpson's, and at one point even left a meeting early at SNL in order to visit Simpson in jail.[154] He was unhappy with the continuing Simpson jokes; though he did not communicate with Macdonald directly, he made his displeasure regarding Macdonald and Update writer Jim Downey known to Michaels regularly. During the 1997–1998 season, Ohlmeyer had Downey removed from the segment, and told Macdonald he could stay, but only under a new writing staff. Macdonald refused to perform the segment without Downey, and was then removed from Update.[154] Colin Quinn was made the new Update anchor.[155] Ohlmeyer later argued that ratings had been declining for the segment under Macdonald, which had not occurred previously during the segment.[156] Macdonald returned to host two years later in 1999, making fun of the firing in his monologue.[157]

The new cast members quickly made an impression and revitalised the show, particularly with sketches like the Spartan Cheerleaders, Mary Katherine Gallagher, and the Roxbury Guys.[158][159] Hammond in particular built up an array of popular impersonations, including Bill Clinton and Chris Matthews.[159] The show focused on performers in this period, and writers were forced to supply material for the cast's existing characters before they could write original sketches.[160] Newer cast members were restricted from filming movies during the season.[149] Shannon, Oteri, and Ana Gasteyer became cast standouts as their characters and impressions gained popularity.[161][162] Journalists said the women's prominence, backed by writers like Paula Pell and later Tina Fey, signaled a shift to a more female-friendly SNL where women had greater visibility.[163] The "rise of women" in SNL would continue with the addition of cast members Rachel Dratch, Maya Rudolph, and Amy Poehler in the next few years (particularly with Fey and Poehler as the first two women-anchor team on Weekend Update), to Kristen Wiig, Kate McKinnon, Cecily Strong, and others in later seasons.[164] Tina Fey would become the show's first female head writer in 1999.[21]

SNL faced new competition during this period in the form of Fox's sketch comedy show Mad TV, which aired a half hour earlier than SNL[165] and featured a more diverse cast.[166] Though Mad TV never posed a serious ratings threat to SNL, it did at times beat the NBC show in some younger demographics.[167][168] A three-hour prime time special aired in September 1999 to celebrate 25 years of the show's airing.[169]

Jimmy Fallon and Fey began hosting Weekend Update as a team in the 2000–2001 season.[170] Fey initially auditioned alone before pairing with Fallon; other auditions included cast members Gasteyer and Chris Parnell.[171] The pairing was an attempt at a more "playful" style compared to previous Update hosts, according to Michaels.[171] This season also contained many sketches focusing on that year's presidential campaign between Al Gore and George W. Bush. The two candidates even appeared (separately) on a special with the cast in fall 2000.[172] Writer Jim Downey coined the term "strategery" via Ferrell's Bush impression, in a sketch mocking Bush's propensity for mispronunciations, while Darrell Hammond's Gore was characterized by his slow, deliberate drawl and use of the term "lockbox".[173] In 2015, Ferrell stated that he thought his impression "humanized" Bush to the country and may have won him the election, and that Hammond's "rigid, robotic-like" take on Gore may have affected Gore's perception also.[174]

September 11 attacks and anthrax scare

[edit]

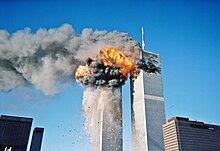

The show's New York City cast and crew were highly impacted by the September 11 attacks in 2001. Many entertainment programs were halted or postponed following the attacks, but late-night programs such as SNL began planning to return to the airwaves.[175] SNL's scheduled Reese Witherspoon episode, the September 29 season premiere for the 2001–2002 season, aired as planned. Producer Steve Higgins later said that he wanted to do something to "bring normalcy back" following the show's return, which occurred twelve days after talk show host David Letterman had returned to the air.[176]

New York mayor Rudy Giuliani spoke at the top of the show standing with NYC firefighters and police officers, including Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik and Fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen, followed by a performance of "The Boxer" from Paul Simon. Giuliani called the emergency workers heroes, which was applauded by the studio audience.[177] He also made mention of the victims of the attacks, hailing them as heroes also.[178] After Michaels asked, "Can we be funny?" Giuliani replied, "Why start now?" to laughter from the audience.[177] The joke was Michaels's idea. Michaels and Giuliani wanted to convey that the city was "open for business" with the episode.[179][176] Giuliani also delivered the show's signature opening line.[180] The episode is considered one of the most memorable in the show's history.[181]

The show took on a more serious tone for the rest of the season, with less political humor.[182] Planned second episode host Ben Stiller dropped out due to the attacks, forcing producers to find a replacement.[176] SNL's 30 Rockefeller Plaza production location was also the subject of an anthrax scare, during the production of Drew Barrymore's episode in October 2001, when an NBC News employee on a lower floor was diagnosed with anthrax after opening a letter in the NBC newsroom. Barrymore considered dropping out of the episode, but decided to continue hosting, citing Giuliani as an inspiration to continue.[182] Head writer Tina Fey later said she had a "panic attack, basically" and left the building, only returning later that night at the urging of Michaels.[176]

New set and 2004 presidential election

[edit]The show received a new set modelled after Grand Central Terminal in 2003.[183] A widely-publicised incident involving singer Ashlee Simpson also occurred during the 2004–2005 season, where she appeared to lip sync during her second performance, appearing flustered when the wrong song was played.[184] Simpson was the only musical performer in the show's history to unexpectedly leave the stage mid-performance, later apologising for the incident and explaining that she had lost her voice earlier in the week.[185]

The 2004–2005 season contained many sketches that focused on the 2004 presidential election between John Kerry and George W. Bush.[186] Innovation & Tech Today called this election "difficult" for the show, due to its relatively safe and restrained rhetorical nature compared to previous elections.[187]

Digital expansion: 2005–2015

[edit]The show switched to high-definition broadcasting for the 2005–2006 season, which required Studio 8H to be fitted with the necessary equipment.[188] Four new featured players were added during this period: Andy Samberg, Bill Hader, Kristen Wiig,[189] and Jason Sudeikis, the latter having been added at the end of the previous season.[190] Hader quickly became popular for his impersonations, such as Vincent Price and Al Pacino, and characters such as New York City correspondent Stefon.[191] Wiig gained popularity with impersonations of Drew Barrymore, Felicity Huffman and Megan Mullally, also creating memorable characters such as the Two A-Holes (with Sudeikis) and Target Lady.[192]

Before the start of the 2006–2007 season, the show suffered budget cuts that resulted in longtime cast members like Chris Parnell and Horatio Sanz being let go.[note 6] In addition, longtime cast members Dratch and Fey left the show to work on the NBC sitcom 30 Rock.[194] The following season was cut short by the 2007–2008 Writers Guild of America strike, which led to several cancelled episodes.[195] During the strike, the show's cast (along with Michael Cera, who acted as host, and musical guest Yo La Tengo) performed an "episode" of the show entitled, Saturday Night Live - On Strike! at the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, co-founded by cast member Amy Poehler in New York City.[195][196] The strike ended in February, and production continued that month for an episode hosted by Fey.[197] To make up for lost time and wages, four episodes were produced back-to-back during this period; this schedule had not been done since the first season in 1976.[198]

SNL Digital Shorts

[edit]

The Lonely Island, a comedy trio composed of Andy Samberg, Akiva Schaffer, and Jorma Taccone, were hired by SNL for the 2005–2006 season, following a writing gig for the 2005 MTV Movie Awards that was hosted by Jimmy Fallon.[199] Fallon's praise, and positive word of mouth to others like Fey and Michaels, had led the trio to audition in mid-2005. Samberg was hired as a cast member, while Schaffer and Taccone joined the writing staff.[200]

Schaffer and Taccone struggled initially, with only two of their sketches making it to air in the first three months.[201] They soon saw success incorporating more video work, deciding to bypass the pitching process, as they were so new to the show that it would have been dismissed as too expensive.[202][203] Their breakthrough was the short "Lazy Sunday" in December 2005, which had spread nationwide[201] and became one of the first viral YouTube videos.[202] It increased the trio's recognisability, particularly Samberg's, nearly overnight.[201] Their success, according to New York, "forced NBC into the iPod age".[204] This newfound popularity led to a record deal for the trio and the creation of the SNL Digital Shorts division, which allowed the group creative freedom to continue producing videos.[203] Michaels was often confused by the trio's pitches, and decided to stop taking their pitches and allow them to self-produce their efforts.[199][205]

The group's rise to fame was highlighted by a combination of "new" and "old" media, as described by Schaffer.[202] Many songs recorded for their 2009 album, Incredibad, and following albums Turtleneck & Chain and The Wack Album, would premiere as Digital Shorts on SNL.[206][207] Schaffer and Taccone left SNL in 2010, but stayed on for following seasons to produce Digital Shorts related to their musical work.[205] Samberg left the show in 2012, later calling the decision difficult, but saying he was stressed and "falling apart" due to the workload.[208]

2008 presidential election

[edit]Fey later returned to the show during the 2008 presidential election for several critically acclaimed guest appearances as vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin.[209] Michaels called Fey in August 2008 about reprising the role, and the first sketch in which she performed alongside Amy Poehler as Hillary Clinton aired on September 13. During this sketch, writer Mike Shoemaker coined the phrase, "I can see Russia from my house", a line frequently misattributed to Palin herself.[210][211]

Fey won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series in 2009 for her impersonation of Palin.[212] Writer Robert Smigel later said it was the show's "biggest moment since the 70s", and Michaels observed that it made Fey a "huge star" and that "you could see perception changing completely".[213] The show's ratings saw a significant increase during this period.[214]

Palin herself appeared on the show on October 18, 2008, watching and critiquing a sketch from a previous episode in which Fey had played her.[215] She did not appear directly alongside Fey, as Fey was "terrified" of anything resembling a political endorsement, according to Michaels.[216]

Fred Armisen played the role of Barack Obama using darkening makeup in the primary season leading up to the election, which was controversial. Michaels defended the decision to cast Armisen, saying that he hired the performer with the "cleanest" take on Obama.[217]

Obama presidency

[edit]Armisen continued to play Obama from 2008 to 2012, following which cast member Jay Pharoah assumed the impression. Pharoah and Killam were let go in 2016.[218] Darrell Hammond left the show in 2009 after fourteen years on the cast, holding the record at the time for the longest-running cast member (later beaten by Kenan Thompson). He holds a record for the most times saying the show's opening line, saying it over seventy times during his tenure.[21][219]

A Facebook campaign was started in early 2010 called "Betty White to Host SNL (please?)!" that garnered the attention of producers at the show. The campaign wound up successful, and White became the oldest person ever to host the show in 2010. For White's episode, Michaels brought back former cast members Rachel Dratch, Tina Fey, Ana Gasteyer, Amy Poehler, Maya Rudolph and Molly Shannon. The episode garnered the show's highest ratings in over a year. with a rating of 5.8 in the 18–49 rating, demographic and with 12.1 million viewers overall.[220]

From 2008, Seth Meyers was the solo host of Weekend Update,[221] before being partnered with Cecily Strong in 2013. After Meyers left for Late Night with Seth Meyers in February 2014, Strong was paired with head writer Colin Jost. However, later that year, she was replaced by writer Michael Che.[222][223] Jost was criticised initially for what some critics saw as a wooden performance,[224] but later received more praise after being paired with Michael Che later in 2014.[225]

Long-time performers Bill Hader, Jason Sudeikis and Fred Armisen all left the show after the 2012–2013 season, which prompted the show to add eight performers over the course of the following season, including Beck Bennett and Kyle Mooney.[148][226] Darrell Hammond succeeded Don Pardo as announcer after his death in August 2014, starting with the 2014–2015 season.[227] The show came under criticism during this period (including from its own cast) for not including at least one black female cast member in the cast.[228] As a result, Michaels announced that the show would be holding auditions for a black female cast member.[229] On January 6, 2014, it was announced that UCB-NY performer Sasheer Zamata would be joining the cast as a featured player. She made her first appearance on January 18, 2014.[230]

The show began to rely more on pre-recorded material and videos more than it ever had before during this period,[231] to the extent that some commentators said it had sometimes outshined live material on the show.[232][233][234]

A three-hour prime time special aired in February 2015 to celebrate 40 years of the show's airing.[235] The special generated 23.1 million viewers, becoming NBC's most-watched prime-time, non-sports, entertainment telecast (excluding Super Bowl lead-outs) since the Friends series finale in 2004.[236][237] It was preceded by an hour-long red carpet special entitled SNL 40th Red Carpet Live, hosted by Matt Lauer, Savannah Guthrie, Carson Daly and Al Roker, who interviewed past hosts, current and previous cast members, and musical guests.[238]

Trump era and new relevance: 2015–present

[edit]2016 presidential election

[edit]The 2015–2016 season coincided with the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election, which brought renewed attention to the show's political sketches.[239] Kate McKinnon portrayed Hillary Clinton during this period, the Democratic nominee, and Clinton herself made a cameo on the show alongside McKinnon in 2015.[240] Larry David also made recurring appearances with a portrayal of Bernie Sanders.[241] Prior to the start of the season, SNL announced that cast member Taran Killam would portray Donald Trump, the Republican nominee, on a recurring basis.[242] Some sketches required Killam to play other primary candidates, necessitating a secondary Trump impressionist. Jimmy Fallon was initially offered the role of Trump on a recurring cameo basis, but a last-minute change resulted in announcer Darrell Hammond portraying Trump, as he had done for fourteen seasons in the cast.[243] Hammond ultimately continued to play Trump on the show for the rest of the season.[244]

Trump himself hosted the show on November 7, 2015, while he was still a candidate for the Republican nomination.[245] His appearance led to protests and letters from Hispanic organizations and other groups, who asked NBC to rescind his hosting invitation.[246] Trump had previously hosted in 2004.[247] The episode garnered an overnight rating of 6.6, the show's largest since 2012.[248] Television critic Bill Carter called the episode "surprisingly mild", given the controversy.[248] Killam later called the appearance "embarrassing and shameful" for the cast in 2017, after he had left the show.[245]

Trump won the election over Clinton in a surprise victory on November 8, 2016.[249] The show's writing staff, initially expecting Clinton to win the election, were taken by surprise and forced to change course on their planned sketches.[250] Dave Chappelle hosted the show's first post-election episode on November 12 with musical guest A Tribe Called Quest.[251] During the cold open, a somber McKinnon (as Clinton) covered Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" at a grand piano, closing by saying, "I'm not giving up and neither should you."[251] The segment was intended both as a tribute to Cohen and as an acknowledgement of the country's divided state following the election.[250] The performance received divided responses; Alan Light of Esquire said it captured the "shock and horror" that much of the audience was feeling from the election,[250] while former cast member Rob Schneider said the show was "over" for good after the performance, accusing the show of "comedic indoctrination".[252] The Chappelle episode earned the show's highest ratings in four years.[250]

First Trump presidency

[edit]The show received positive attention for a recurring impression of Trump by actor Alec Baldwin. Baldwin's impression debuted during the 2016 campaign season and quickly became a recurring feature on the show. His exaggerated depiction of Trump, often highlighting the president's speech patterns, gestures, and persona, drew considerable attention.[253] McKinnon also played a number of political figures and Trump administration officials during the first Trump presidency, including Jeff Sessions, Kellyanne Conway, and Betsy DeVos.[254] The show's ratings significantly increased during this period, and SNL received a "shot of relevance", according to Vanity Fair's Joanna Robinson.[255] Baldwin won an Emmy for his performance.[256] The show began to air live coast-to-coast on April 15, 2017, as a trial run for the final four episodes of the 2016–2017 season;[257] NBC Entertainment Chairman Robert Greenblatt said that the show's significantly increased viewership and engagement had led to the decision.[258] This change was made permanent in September 2017.[259]

Trump would tweet about the show several times throughout his first presidency, criticising it for what he saw as one-sided coverage and questioning if the FCC should investigate the show.[260] Some outlets, like Paste and Vox, criticised the show's perceived over-reliance on Trump humor during this period, and what they saw as hypocrisy after allowing Trump to host the show as a presidential candidate.[261][262] Baldwin called his appearances as Trump "agony" in March 2018.[263] He retired the impression after the 2020 election,[264] and cast member James Austin Johnson assumed the impression in November 2021.[265]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, SNL's 2019–2020 season was indefinitely halted on March 16, 2020. The move came hours after New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio ordered all theaters in the city to close by the following morning.[266] The season resumed on April 11, 2020 with three remotely produced episodes labelled Saturday Night Live at Home, containing Weekend Update and other contributions from the cast in their homes.[267] The first remote episode was hosted by Tom Hanks, who was diagnosed with COVID-19 the month prior.[268] The third of these episodes, airing on May 9, 2020 and hosted by longtime former cast member Kristen Wiig, served as the season's finale.[269]

A December 2021 episode planned to feature host Paul Rudd and musical guest Charli XCX was forced to air without a live audience and musical guest, with limited cast and crew, due to a significant rise in cases of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in New York at the time.[270]

Joe Biden was played by Jim Carrey through the 2020 presidential election.[271] Alex Moffat succeeded Carrey as Biden in November, after the election.[272] Dave Chappelle hosted the first episode following the election, in which Biden was elected President, on November 7, 2020.[273]

Post-pandemic and fiftieth anniversary

[edit]The comedy troupe Please Don't Destroy, consisting of Ben Marshall, John Higgins, and Martin Herlihy, were hired as writers in 2021 and began contributing their short films to the show.[274] Their prerecorded sketches featured on the show usually include celebrity performers, such as Taylor Swift in a "Three Sad Virgins" sketch in November 2021. Billboard said the group had "capably picked up the digital short mantle" left on the show by The Lonely Island.[275]

The show has experimented with different avenues of broadcasting and digital content in recent years. Episodes were streamed live on the Peacock streaming service simultaneously with the TV airings beginning in the 2021–2022 season.[276] The show also experimented with live broadcasts on YouTube, beginning with a 2021 Elon Musk-hosted episode.[277]

The Hollywood Reporter said that the cast overhaul prior to the 2022–2023 season, in which eight cast members left including long-time cast members such as Kate McKinnon, Aidy Bryant, and Pete Davidson, had been the "biggest [...] in a generation". Michaels referred to ongoing disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic as the reason for the large exodus, saying cast members had lacked access to work that they would usually be able to find after leaving SNL.[148][278] For the 2022-2023 season, the show hired 4 stand-up comedians, including Marcello Hernandez, Michael Longfellow, and Devon Walker (hiring so many stand-ups around this time is something that Michaels also attributed to the pandemic).[279] Midway through the season, longtime cast member Cecily Strong exited the show. Becoming the longest-tenured female cast member in the show's history.[280] However, that season ended a month early in April 2023, due to the 2023 Writers Guild of America strike.[281] Due to the strike, the 2023–2024 season was delayed until October 14, 2023.[282]

The show's coverage from 2023 onwards has incorporated sketches about the upcoming 2024 presidential election. On July 31, it was announced that Maya Rudolph would return to portray Presidential nominee Kamala Harris through the 2024 election season.[283]

In January 2024, Variety said that "speculation [had] been rampant for years" that Michaels would retire from the series after its fiftieth season, premiering in 2024.[284] Michaels told Entertainment Tonight that month that former head writer and cast member Tina Fey could "easily" be his successor, were he to step down, but said he had not made a decision yet at that point. Michaels has worked with Fey several times since her SNL tenure ended, including on 30 Rock.[285] Michaels earlier said in 2021 that the show's fiftieth anniversary would be "a really good time to leave".[286] Kenan Thompson, the show's longest-serving cast member, speculated in 2022 that SNL may come to an end altogether after its fiftieth season, saying that it could make financial sense for NBC.[287] However, in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter in September 2024, Michaels denied that he was retiring at the end of the season.[288]

A three-hour prime-time live broadcast to celebrate the series' history will air on February 16, 2025.[289]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The original title was used because the Saturday Night Live title was in use by Saturday Night Live with Howard Cosell on rival network ABC. After the cancellation of Cosell's show in 1976, NBC purchased the rights to the name and officially changed the show's name to Saturday Night Live at the start of the 1977–1978 season.[2][21][22]

- ^ Dave Wilson, SNL's long-time director, later said that the show was in fact broadcast live, as his crew did not know how to work the delay.[32] However, the first edition of The Book of Lists, describing the broadcast, indicated that two words were deleted from the broadcast during Pryor's opening monologue, although what was censored is not specified.[29]

- ^ Chase had been hired on a one-year writer contract, and had refused to sign the performer contract that was repeatedly offered to him. This had allowed him to leave the show for other ventures after just one year as a performer.[16]

- ^ Talent coordinator Neil Levy claimed Murphy contacted and pleaded with him for a role on the show and, after seeing him audition, Levy fought with Doumanian to cast him instead of Robert Townsend. Doumanian also claimed credit for discovering Murphy and fighting with NBC executives to bring him onto the show.[98]

- ^ Nolte was booked to host the show, but had cancelled just four days before showtime. Ebersol offered Murphy the chance to host, a move that Piscopo would perceive as a major slight. Piscopo would later claim that Ebersol used Murphy's success to divide the two erstwhile friends and play them against one another.[101]

- ^ This was the second time Parnell had been fired from the show due to budget cuts, the first being after the 2000–2001 season ended.[193]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Henry & Henry 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Wilson Hunt, Stacy (April 22, 2011). "A Rare Glimpse Inside the Empire of 'SNL's' Lorne Michaels". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hammill 2004, p. 2008.

- ^ Greenfield, Jeff (February 11, 2015). "New York Magazine's Original 1975 Review of Saturday Night Live". Vulture. Archived from the original on February 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shaw, Gabbi; Olito, Frank (December 20, 2022). "WHERE ARE THEY NOW: All 162 cast members in 'Saturday Night Live' history". Business Insider. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Marx, Sienkiewicz & Becker 2013, p. 6.

- ^ a b Atwater, Carleton (December 7, 2010). "Looking Back at the First Five Years of SNL". Vulture. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 59.

- ^ a b Wayne, Teddy (October 29, 2013). "The Lowest Form of Humor: How the National Lampoon Shaped the Way We Laugh Now". The Millions. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (July 3, 2005). "National Lampoon Grows Up By Dumbing Down". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Wright, Megh (November 4, 2014). "Saturday Night's Children: Michael O'Donoghue (1975)". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 19, 2023. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 34–39.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, p. 23.

- ^ Wright, Megh (July 23, 2013). "Saturday Night's Children: George Coe (1975-1976)". Vulture. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Jeremy (March 11, 2023). "How Lord Of The Rings Composer Howard Shore Built The Original Saturday Night Live Band". /Film. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 21.

- ^ Tropiano 2013, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, Abby; Clair, Fiona (October 2, 2021). "22 things you probably never knew about 'Saturday Night Live'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Rothman, Lily (September 26, 2014). "The Surprising Story Behind Saturday Night Live's Most Famous Line". TIME. Retrieved August 19, 2024.

- ^ "Remembering Carlin on the "SNL" Premiere". Variety. June 23, 2008. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Sheff-Cahan, Vicki; Schindehette, Susan; Park, Jeannie (September 25, 1989). "'Saturday Night Live' !". People. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Top 10 Post-SNL Careers". TIME. June 5, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 94.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Henry & Henry 2013, p. 168.

- ^ a b Wallechinsky, Wallace & Wallace 1977, p. 217.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b Walfisz, Jonny (December 13, 2023). "Culture Re-View: Why Richard Pryor caused NBC to add a time delay to Saturday Night Live". Euronews. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Henry & Henry 2013, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 117–118.

- ^ "50 Greatest 'Saturday Night Live' Sketches of All Time". Rolling Stone. February 3, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Ventre, Michael (December 11, 2005). "Like 'Daddy Rich,' Pryor was a true king". TODAY. NBC News. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 103–104, 193.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 103–104, 313.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Tinnin, Drew (January 10, 2023). "One Of Chevy Chase's Most Famous Saturday Night Live Bits Sent Him Straight To The Hospital". /Film. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Edgers, Geoff (September 19, 2018). "Chevy Chase can't change". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 46, 101.

- ^ Rome, Emily (January 15, 2016). "On this day in pop culture history: Bill Murray replaced Chevy Chase on 'SNL'". Uproxx. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 314–315.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Peters, Fletcher (June 18, 2021). "Bill Murray and Chevy Chase's Infamous Fight Was "Awful," Say 'SNL' Co-stars". Decider. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Keller, Richard (April 17, 2008). "The Not Ready for Prime-Time Players who made it to the big time: 1975–1985". AOL. Archived from the original on August 3, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 308.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2002, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 313.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 341.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 338–339.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 352.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 343.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 359.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 344–346.

- ^ a b c Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 353.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 153.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 238.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 354–356.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 344–347.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20180417184338/http://www.nbc.com/saturday-night-live/explore/season-3

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 358.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, p. 288.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 178–182.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Wright, Megh (February 6, 2013). "Saturday Night's Children: Brian Doyle-Murray (1979-1980; 1981-1982)". Vulture. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 191–192, 195.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 387.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Schwartz, Tony (January 11, 1981). "Whatever happened to TV's 'Saturday Night Live'?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 412.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 175.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 431–433.

- ^ DeSantis, Rachel (February 6, 2017). "Saturday Night Live: A history of F-bombs". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 202.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (September 5, 2012). "How Bad Can It Be? Case File #23: Saturday Night Live's aborted 1980-81 season". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 207.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 209.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 441–444.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 449, 457.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 222–225.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 452.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 270.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 219.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 472.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 229.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Meaney, Jake (October 14, 2010). "'Saturday Night Live: The Best of Eddie Murphy' Brings on Bursts of Genius". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ a b Hill & Weingrad 1986, pp. 465–467.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, p. 255.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 286.

- ^ Hill & Weingrad 1986, p. 474.

- ^ a b Saturday Night Live in the '80s: Lost and Found (Documentary). November 13, 2005. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Atwater, Carleton (January 6, 2011). "Looking Back at Saturday Night Live, 1980-1985". Vulture. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b Bennetts, Leslie (December 12, 1985). "Struggles at the New 'Saturday Night'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (October 3, 2012). "Younger, Sexier, Inherently Doomed Case File #25: Saturday Night Live's 1985-1986 season". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 307.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 308–313.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 288, 294.

- ^ Grein, Paul (October 9, 2023). "Here's the Host & Musical Guest for Every 'Saturday Night Live' Season Premiere". Billboard. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (September 27, 2013). "The 8 Biggest Transitional Seasons in 'SNL' History". Vulture. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Ryan (July 25, 1987). "Well, Isn't He Special?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 3, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, Lynn (April 17, 1987). "On the Cover: "You can't compete with a memory," says Lorne Michaels". The Vindicator. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan 2014, p. 13.

- ^ Adalian, Josef (June 2, 2017). "How Each Era of SNL Has Ridiculed American Presidents". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 319.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 749.

- ^ Hanauer, Joan (September 20, 1989). "'SNL' celebrates 15th anny reunion". United Press International. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 332–337.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 358.

- ^ a b c Siegel, Alan (September 11, 2019). "Comedy in the '90s, Part 3: The Bad Boys of 'Saturday Night Live'". The Ringer. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 374.

- ^ Fallon, Kevin (June 14, 2015). "The Secrets of 'Saturday Night Live': Where Comedy Legends Are Born". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 360.

- ^ "Wayne's World". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Fox, David J. (March 3, 1992). "Weekend Box Office 'Wayne's World' Keeps Partyin' On". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 372.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 421.

- ^ a b Tapper, Jake (October 13, 2002). "Sin". Salon. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Murray, Noel (March 7, 2006). "Inventory: Ten Memorable Saturday Night Live Musical Moments". A.V. Club. The Onion. Retrieved June 19, 2015.

- ^ Gajanan, Mahita (July 26, 2023). "The Controversial Saturday Night Live Performance That Made Sinéad O'Connor an Icon". TIME. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Curtis, Bryan (August 27, 2014). "The Glue". Grantland. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 395.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 415–416.

- ^ Crouch, Ian (October 21, 2014). "The Nine Lives of "Saturday Night Live"". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 26, 2024. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Chris (March 13, 1995). "How 'Saturday Night Live' Became a Grim Joke". New York. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (July 14, 2016). "Everything old is new again case file #65: the 1994-95 season of Saturday Night Live". The A.V. Club. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 413–414.

- ^ "SNL new and improved". Ellensburg Daily Record. The Associated Press. September 27, 1995. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Porter, Rick (September 30, 2022). "Breaking Down 'SNL's' Biggest Cast Overhaul in a Generation". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Hall, Jane (July 14, 1995). "NBC Looks to Restore the Shine on 'SNL'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ "Another 'SNL' Shakeup Note: Long-Time Bandleader Bopped". New York Daily News. August 28, 1995. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

- ^ "Saturday Night's Alright for Firing". New York. June 12, 1995. p. 17. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Steve (October 4, 1995). "Jury still out on new 'SNL'". Chicago Tribune. p. C3. Retrieved May 28, 2024 – via Herald-Journal.

- ^ Mink, Eric (October 5, 1995). "New 'SNL' season is critical for show". New York Daily News. Retrieved May 28, 2024 – via Rome News-Tribune.

- ^ a b c d Edgers, Geoff (April 12, 2024). "The unlikely but enduring bond between Norm Macdonald and O.J. Simpson". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 24, 2024. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 432.

- ^ Jackson, Dory (September 14, 2021). "Norm Macdonald's Best Moments from His Time on 'Saturday Night Live' — Watch". People. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Saturday Night Live in the '90s: Pop Culture Nation (Television production). 2007.

- ^ a b "The 'Doctor' Is In". Chicago Tribune. May 14, 1996. Archived from the original on May 19, 2024. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 427.

- ^ Kohen 2012, p. 264.

- ^ Saturday Night Live in the '90s: Pop Culture Nation (Television production). 2007. Event occurs at 1:10:36.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 173–190.

- ^ Nussbaum, Emily (May 11, 2003). "TELEVISION/RADIO: RERUNS; It's the Revenge of the Ignorant Sluts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Boedeker, Hal (October 14, 1995). "'Mad TV' Clobbers 'SNL'". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ Funk, Tim (July 21, 1995). "'Saturday Night Dead' to be renovated". Ocala Star-Banner. Knight-Ridder Newspapers. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ Bellafante, Ginia (February 12, 1996). "Television: The Battle For Saturday Night". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ Greiving, Tim (May 18, 2016). "An Oral History of MADtv, the Sketch Show That Never Quite Changed Comedy". Vulture. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ "Saturday Night Live: The 25th Anniversary Special". Emmy Awards. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ Gray, Ellen (December 30, 2000). "Head writer: Timing helped her land job". The Vindicator. Knight Ridder Newspapers. p. B13. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ a b Baldwin, Kristen (May 10, 2002). "Tina Fey and Jimmy Fallon: Update With Destiny". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa (November 2, 2000). "Taped From New York, It's the Candidates on 'Saturday Night'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024.

- ^ McGee, Ryan; Fear, David; Murray, Noel (August 22, 2017). "20 Best 'Saturday Night Live' Political Sketches". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ Guerrasio, Jason (April 17, 2015). "Will Ferrell thinks his 'SNL' portrayal of George W. Bush influenced the 2000 election". Business Insider. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ Walfisz, Jonny (September 11, 2023). "Culture Re-View: How 9/11 changed films, music and books for two decades". Euronews. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Dickson, EJ; Greene, Andy (September 8, 2021). "'In Bad Times, People Turn to the Show': Inside the 9/11 Episode of 'SNL'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ a b "NYC Mayor on SNL: It's OK to Laugh". ABC News. October 3, 2001. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ McGahan, Michelle (September 11, 2015). "A Look Back At SNL's Powerful 9/11 Tribute". Bustle. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (April 14, 2010). "Saturday Night Live in the 2000s: Time and Again". Variety. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, p. 504.

- ^ Rosario, Alexandra Del (September 11, 2021). "Ming-Na Wen & 'SNL's Keith Ian Raywood Reflect On 9/11 At Creative Arts Emmys: "Twenty Years Ago Completely Changed Our Lives"". Deadline. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b "SNL Goes on Despite Anthrax Scare". ABC News. October 16, 2001. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela; Adalian, Josef (September 25, 2003). "SNL primed for 29". Variety. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ "Ashlee Simpson takes 'SNL' lip sync blame". TODAY. NBC News. October 28, 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ Leung, Rebecca (October 28, 2004). "Michaels: Lip-Sync An 'SNL' No-No". CBS News. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- ^ "'SNL' presenting special for election". The Spokesman-Review. November 1, 2004. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ "How SNL's Political Hamming Has Impacted Real-World Politics". Innovation & Tech Today. March 25, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ Kaplan, Don (April 27, 2005). "'SNL' Goes High-Def". New York Post. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ Coyle, Jake (February 4, 2006). "Venerable 'SNL' undergoing another generational shift"". Arizona Republic. The Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 19, 2006. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ "Kansan Jason Sudeikis establishes comedic footing on 'SNL'". Lawrence Journal-World. October 28, 2005. pp. 1E, 3E. Retrieved May 25, 2024.

- ^ Wright, Megh (January 7, 2014). "Saturday Night's Children: Bill Hader (2005-2013)". Vulture. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ Blake, Meredith (July 21, 2012). "SNL cast gets sketchier at awkward time for NBC". Winnipeg Free Press. Archived from the original on June 5, 2024. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 513–514.

- ^ Carter, Bill (September 21, 2006). "Bowing to Budget Cuts at NBC, 'Saturday Night Live' Pares Five Performers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Ryzik, Melena (November 19, 2007). "Strike or No Strike, for a Select Few, Saturday Night Was Live". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ "SNL stages two-hour live theatre show in Manhattan". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. November 18, 2007. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008.

- ^ "After strike, 'Saturday Night Live' works to retrieve audience". The New York Times. February 20, 2008. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Carter, Bill (February 21, 2008). "'SNL' Is Ready to Make Up for Lost Time". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 3, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Becker, Marx & Sienkiewicz 2013, pp. 236–245.

- ^ Jardin, Xeni (September 30, 2005). "Open Source Opens Doors to SNL". WIRED. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Itzkoff, Dave (December 27, 2005). "Nerds in the Hood, Stars on the Web". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 31, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c Echlin, Hobey (April 30, 2013). "The Lonely Island Guys Prove Once Again Why They're the Internet's Biggest Stars". Paper. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ a b McGurk, Stuart (April 10, 2012). "The Hits Squad". GQ. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Influentials: TV and Radio". New York. May 3, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Heisler, Steve (May 24, 2011). "Interview: The Lonely Island". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (May 18, 2011). "The Lonely Island: Turtleneck & Chain Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Czajkowski, Elise (June 10, 2013). "Talking to The Lonely Island About 'The Wack Album', 'SNL', and Why They Haven't Done a Live Show Yet". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (July 11, 2024). "Andy Samberg Opens Up About 'Difficult' Decision to Leave 'SNL': 'I Was Falling Apart in My Life'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Poniewozik, James (September 14, 2008). "Fey's Palin? Not Failin'". TIME. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Poehler, Amy (October 29, 2014). "Amy Poehler on What It Was Like to Tape Saturday Night Live While Pregnant". Vulture. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 587–588.

- ^ O'Neil, Tom (September 13, 2009). "You betcha - Tina Fey wins Emmy as Sarah Palin on 'SNL'". The Envelope. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 586–589.

- ^ Stelter, Brian (September 14, 2008). "'SNL' Sees Its Ratings Soar". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Hamby, Peter; Hornick, Ed (October 18, 2008). "Sarah Palin appears on 'Saturday Night Live'". CNN. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Shales & Miller 2015, pp. 590–591.

- ^ Izadi, Elahe (September 3, 2016). "The most memorable comedy moments of the Obama presidency". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Joanna (August 9, 2016). "Eight Years Later, S.N.L. Still Has an Obama Problem". Vanity Fair. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ Gallagher, Danny (October 4, 2023). "A Look at Some of the Longest-Running SNL Cast Members and What Kept Them on Air". Paste. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ Seidman, Robert (May 13, 2010). "Update: Betty White Hosting Turn on "Saturday Night Live" Averages 12.1 Million Viewers and a 4.6 Rating With Adults 18–49". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on June 25, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Gross, Doug (September 15, 2009). "Seth Meyers says he'll man 'SNL' Update desk alone". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Cooper (January 23, 2014). "'SNL' head writer to join Cecily Strong as 'Weekend Update' co-anchor shingbauer". Today. NBC News. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ^ Ge, Linda; Maglio, Tony (September 11, 2014). "Saturday Night Live' Replaces Cecily Strong With Michael Che as 'Weekend Update' Anchor". Yahoo!. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Greenberg, Rudi (March 5, 2014). "When a 'Weekend Update' anchor is as mediocre as Colin Jost, all you can do is shrug". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 16, 2024. Retrieved August 25, 2024.

- ^ Rowles, Dustin (April 17, 2023). "'Update' Anchors Michael Che and Colin Jost Are Good at their Jobs". Pajiba. Retrieved August 25, 2024.