Geraldo Rivera

Geraldo Rivera | |

|---|---|

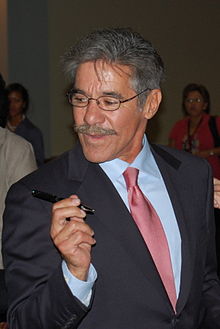

Rivera in 2011 | |

| Born | Gerald Michael Rivera July 4, 1943 Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Arizona Brooklyn Law School |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, talk show host, writer, attorney |

| Years active | 1980–present |

| Organization | Fox News Channel |

| Television | Geraldo Geraldo at Large The Five |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Linda Coblentz (m. 1965–1969)Sherryl Raymond

(m. 1976–1984)C.C. Dyer (m. 1987–2000)Erica Michelle Levy (m. 2003) |

| Children | 6 |

| Family | Craig Rivera (brother) |

| Website | www |

Gerald Michael Rivera (born July 4, 1943),[2] better known as Geraldo Rivera (/ˌhɜːrˈɔːldoʊ ˌrɪˈvɛrə/),[3] is an American attorney, reporter, author, and talk show host. He was the host of the talk show Geraldo from 1987 to 1998. Rivera hosted the newsmagazine program Geraldo at Large, hosts the occasional broadcast of Geraldo Rivera Reports (in lieu of hosting At Large), and appears regularly on Fox News Channel programs such as The Five.

Early life

Rivera was born at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York City, New York, the son of Lillian (née Friedman) and Cruz "Allen" Rivera (October 1, 1915 – November 1987), a restaurant worker and cab driver.[4][5] Rivera's father was a Catholic Puerto Rican,[6] and his mother is of Ashkenazi Russian Jewish descent. He was raised "mostly Jewish" and had a Bar Mitzvah ceremony.[7][8] He grew up in Brooklyn and West Babylon, New York, where he attended West Babylon High School. Rivera's family was sometimes subjected to prejudice and racism, and took to spelling their surname as "Riviera" because they thought it sounded "less ethnic".[9]

From September 1961 to May 1963, he attended the State University of New York Maritime College, where he was a member of the rowing team.[10][11] In 1965, Rivera graduated from the University of Arizona (where he continued his involvement in athletics as a goalie on the lacrosse team) with a B.S. degree in business administration.

Following a series of jobs ranging from clothing salesman to short-order cook, Rivera enrolled at Brooklyn Law School in 1966. As a law student, he held internships with the New York County District Attorney under legendary crime-fighter Frank Hogan and Harlem Assertion of Rights (a community-based provider of legal services) before receiving his J.D. near the top of his class in 1969. He then held a Reginald Heber Smith Fellowship in poverty law at the University of Pennsylvania Law School in the summer of 1969 before being admitted to the New York State Bar later that year.[12]

After working with such organizations as the lower Manhattan-based Community Action for Legal Services and the National Lawyers Guild, Rivera became a frequent attorney for the Puerto Rican activist group, the Young Lords, eventually precipitating his entry into private practice.[13][14] This work attracted the attention of WABC-TV news director Al Primo when Rivera was interviewed about the group's occupation of an East Harlem church in 1969. Primo offered Rivera a job as a reporter but was unhappy with the first name "Gerald" (he wanted something more identifiably Latino) so they agreed to go with the pronunciation used by the Puerto Rican side of Rivera's family: Geraldo.[15] Due to his dearth of journalistic experience, ABC arranged for Rivera to study introductory broadcast journalism under Fred Friendly in the Ford Foundation-funded Summer Program in Journalism for Members of Minority Groups at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in 1970.[13][16]

Career

Early stages

Rivera was hired by WABC-TV in 1970 as a reporter for Eyewitness News. In 1972, he garnered national attention and won a Peabody Award[17][18] for his report on the neglect and abuse of patients with intellectual disabilities at Staten Island's Willowbrook State School, and he began to appear on ABC national programs such as 20/20 and Nightline. After John Lennon watched Rivera's report on the patients at Willowbrook, he and Rivera put on a benefit concert called "One to One" (released in 1986 as Live in New York City).

Around this time, Rivera also began hosting ABC's Good Night America. The show featured the famous refrain from Arlo Guthrie's hit "City of New Orleans" (written by Steve Goodman) as the theme. A 1975 episode of the program, featuring Dick Gregory and Robert J. Groden, showed the first national telecast of the historic Zapruder Film.[19]

In October 1985, ABC's Roone Arledge refused to air a report done by Sylvia Chase for 20/20 on the relationship between Marilyn Monroe and John and Robert Kennedy. Rivera publicly criticized Arledge's journalistic integrity, claiming that his friendship with the Kennedy family (for example, Pierre Salinger, a former Kennedy aide, worked for ABC News at the time) had caused him to spike the story; as a result, Rivera was fired. During a Fox News interview with Megan Kelly aired May 15, 2015, Rivera stated the official reason given for the firing was that he violated ABC policy when he donated $200 to a non-partisan mayoral race candidate.[vague]

On April 21, 1986, Rivera hosted The Mystery of Al Capone's Vaults. The special broadcast was billed as the unearthing of Capone's secret vaults located under the old Lexington Hotel in Chicago. Millions of people watched the 2-hour show, but all that they uncovered was dirt. Recently, Rivera told the Chicago Tribune, "It was an amazingly high profile program — maybe the highest profile program I've ever been associated with." [20]

Talk shows, specials and guest appearances

In 1987, Rivera began producing and hosting the daytime talk show Geraldo, which ran for 11 years. The show featured controversial guests and theatricality, which led to the characterization of his show as "Trash TV" by Newsweek and two United States senators.[21] One early show was titled "Men in Lace Panties and the Women Who Love Them". In another in 1988, Rivera's nose was broken in a well-publicized brawl during a show whose guests included white supremacists, antiracist skinheads, black activist Roy Innis, and Jewish activists.[22]

From 1994 to 2001, Rivera hosted Rivera Live, a CNBC evening news and interview show which aired on weeknights.[23]

Fox News to present

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he accepted a pay cut and went to work for the Fox News Channel as a war correspondent in November 2001. Rivera's brother Craig accompanied him as a cameraman on assignments in Afghanistan.

In 2001, during the War in Afghanistan, Rivera was derided for a report in which he claimed to be at the scene of a friendly fire incident; it was later revealed he was actually 300 miles away. Rivera blamed a minor misunderstanding for the discrepancy.[24]

Controversy arose in early 2003, while Rivera was traveling with the 101st Airborne Division in Iraq. During a Fox News broadcast, Rivera began to disclose an upcoming operation, even going so far as to draw a map in the sand for his audience. The military immediately issued a firm denunciation of his actions, saying it put the operation at risk; Rivera was expelled from Iraq.[25][26] Two days later, he announced that he would be reporting on the Iraq conflict from Kuwait.[27]

In 2005, Rivera engaged in a feud with The New York Times over their allegations that he pushed aside a member of a rescue team in order to be filmed "assisting" a woman in a wheelchair down some steps in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. The ensuing controversy caused Rivera to appear on television and demand a retraction from the Times. He further threatened to sue the paper if one was not provided.[28]

In 2007, Geraldo was involved in a dispute with fellow Fox colleague Michelle Malkin. Malkin announced that she would not return to The O'Reilly Factor, claiming that Fox News had mishandled a dispute over derogatory statements Rivera had made about her in a Boston Globe interview. Rivera, while objecting to her views on immigration, said, "Michelle Malkin is the most vile, hateful commentator I've ever met in my life. She actually believes that neighbors should start snitching out neighbors, and we should be deporting people." He added, "It's good she's in D.C., and I'm in New York. I'd spit on her if I saw her." Rivera later apologized for his comments.[29][30]

In 2008, Rivera's book, titled HisPanic: Why Americans Fear Hispanics in the U.S., was released.[31]

On January 3, 2012, Rivera began hosting a weekday radio talk show on 77 WABC in New York, N.Y.[32] The show was scheduled in the two hours between Imus in the Morning and The Rush Limbaugh Show on WABC. On January 30, 2012, Rivera also began hosting a weekday show on Talk Radio 790 KABC in Los Angeles.[33]

On March 23, 2012, Rivera made controversial comments regarding Trayvon Martin's hoodie and how the hoodie was connected to Martin's shooting death, and as of November 5, 2014, he continues to do so as he did on the Dan LeBatard Radio Show on ESPN.[34] Rivera apologized for any offense that he caused with the comments, of which even Rivera's son Gabriel was "ashamed".[35] Some, have reportedly taken the apology as disingenuous;[36] among those who did not accept it was Rivera's longtime friend Russell Simmons.[37] He later apologized to Trayvon Martin's parents as well.[38]

Rivera planned to visit Iraq in April 2012, for what he promised his wife would be his last (and eleventh) visit.[39]

Although he considered running as a Republican in the United States Senate special election in New Jersey, 2013 (to fill the Senate seat left vacant by the death of Frank Lautenberg), he eventually decided not to stand for election.[40]

Present

In 2015, Rivera competed on the 14th season of the television series The Celebrity Apprentice, where he ultimately placed second to TV personality Leeza Gibbons. However, Rivera still raised the highest amount of money out of any contestant in the season, with $726,000 (just $12,000 more than Gibbons).

Rivera hosts the newsmagazine program Geraldo at Large and appears regularly on Fox News Channel. He hosts the talk radio show Geraldo Show on WABC 770 AM radio every weekday. On November 13, 2015, Rivera revealed on Fox News that his daughter, Simone Cruickshank, was at the Stade de France when the attacks and explosions occurred; fortunately, she and her friends made it out alive and would be returning safely home.[41]

On March 8, 2016, Rivera was announced as one of the celebrities who will compete on season 22 of Dancing with the Stars. He was partnered with professional dancer Edyta Śliwińska.[42] On March 28, 2016, Rivera and Śliwińska were the first couple to be eliminated from the competition.[43]

Personal life

Rivera has been married five times:

- Linda Coblentz (1965–69, divorced)

- Edith Vonnegut (December 14, 1971–75, divorced)

- Sherryl Raymond (December 31, 1976–84, divorced)

son: Gabriel Miguel (born July 1979)[44][45] - C.C. (Cynthia Cruickshank) Dyer (July 11, 1987 – 2000, divorced)

daughters: Isabella Holmes (born 1992)[46] and Simone Cruickshank (born 1994) - Erica Michelle Levy (since August 2003)

daughter: Sol Liliana (born 2005)[47]

Rivera is a resident of Edgewater, New Jersey.[48] He previously resided in Middletown Township, New Jersey at Rough Point, an 1895 shingle-style estate.[49]

Rivera is an active sailor. As owner and skipper of the sailing vessel 'Voyager', he has participated in Marion-Bermuda races in 1985, 2005, 2011, and most recently, 2013. In 2013, his vessel finished in 10th place out of 12 finishers in the Class "A" category.[50]

Geraldo also sailed S/V 'Voyager' 1,400 miles up the Amazon river and around the world, going so far as to meet the King of Tonga on the international dateline in time for the new millennium. The adventures were chronicled in eight hour long specials on The Travel Channel,[51] and some of this footage remains available on Geraldo's website.[52]

Author

- Rivera, Geraldo (1972). Willowbrook: A report on how it is and why it doesn't have to be that way. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-71844-5.

- Rivera, Geraldo (1973). Miguel Robles—So Far. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-253900-X.

- Rivera, Geraldo (1973). Puerto Rico: Island of Contrasts, pictures by William Negron. Parents Magazine Press. ISBN 0-8193-0683-5.

- Rivera, Geraldo (1977). A Special Kind of Courage: Profiles of young Americans. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-10501-9.

- Rivera, Geraldo (1992). Exposing Myself. London: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-29874-7.

- Rivera, Geraldo (2008). HisPanic: Why Americans fear Hispanics in the U. S. New York: Celebra. ISBN 0-451-22414-0.

- Rivera, Geraldo (2009). The Great Progression: How Hispanics Will Lead America to a New Era of Prosperity. New York: New American Library. ISBN 0-451-22881-2.

See also

References

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera: 'The Jews Need Me Right Now' –". Forward.com. May 23, 2003. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera Biography". Biography.com. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera Was Born 'Jerry Rivers'?". Snopes.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Excerpt: "His Panic" – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. February 26, 2008. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera Biography (1943-)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Excerpt: "His Panic"". ABC News. February 26, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Biography for Geraldo Rivera". IMDb.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Miller, Gerri. "InterfaithFamily". InterfaithFamily.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Wood, Jamie Martinez (2007). Latino Writers and Journalists. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8160-6422-9.

- ^ – Sailing Book (continues). Geraldo.com. Retrieved on December 17, 2011.

- ^ Fort Schuyler Maritime Alumni Association. Fsmaa.org. (September 24, 1998) Retrieved on December 17, 2011.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=NLPrMMKmynwC&pg=PA364&dq=geraldo+rivera+smith+fellow&hl=en&sa=X&ei=j0uQVc6KE8bp-AGftI3QCg&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=geraldo%20rivera%20smith%20fellow&f=false

- ^ a b "Notable Caribbeans and Caribbean Americans". google.com. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ Bloom, Joshua; Martin, Waldo E., Jr. (January 2013). Black against Empire. University of California Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-520-27185-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Urban Legend about Geraldo Rivera's name being changed from Jerry Rivers". Snopes.com. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ "Pulitzer's School". google.com. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ^ Powers, Ron (1977). The Newscasters: The News Business as Show Business. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 185. ISBN 0312572085.

- ^ See also List of Peabody Award winners (1970–1979)#1972

- ^ Ron Rosenbaum (September 2013). "What Does the Zapruder Film Really Tell Us?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- ^ Kori Rumore (April 22, 2016). "For its 30th anniversary, we watched 'Al Capone's Vaults' with Geraldo Rivera so you didn't have to". Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "TWO DEMOCRATIC SENATORS JOIN BENNETT'S CRUSADE AGAINST `TRASH TV'" (newspaper). Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. December 8, 1995. p. 26. Retrieved March 2, 2009.

Two Democratic senators are joining Friday with William Bennett... to criticize advertisers who support what critics call 'trash TV' talk shows... In television and radio ads to begin airing Friday, Bennett and Sens. Joseph Lieberman (D-Conn.) and Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) urge companies to withdraw advertising dollars from... [shows including] 'Geraldo,'

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera's Nose Broken In Scuffle on His Talk Show". New York Times. November 4, 1988. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Beatty, Sally (November 2, 2001). "Geraldo Rivera to Leave CNBC For Fox and, Then, to Cover War". Wall Street Journal. New York, NY.

- ^ "Gun-toting Geraldo under fire for the story that never was", The Daily Telegraph, December 20, 2001

- ^ Plante, Chris (March 31, 2003). "Military kicks Geraldo out of Iraq". CNN. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- ^ Carr, David (April 1, 2003). "A NATION AT WAR: COVERAGE; Pentagon Says Geraldo Rivera Will Be Removed From Iraq". The New York Times. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera apologizes for breaking reporting rules in Iraq". Legacy.utsandiego.com. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera might sue The New York Times". TV Squad. September 7, 2005. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Shanahan, Mark. "Making waves: controversial celebrity newsman Geraldo Rivera", The Boston Globe, September 1, 2007.

- ^ Malkin, Michelle. "Geraldo Rivera unhinged", MichelleMalkin.com, September 1, 2007.

- ^ Rivera, Geraldo. "Rivera Takes on Anti-Immigrant Fervor in 'His Panic'". NPR. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ^ Brian Stelter (December 11, 2011). "Geraldo Rivera Gets Talk Deal on WABC Radio". The New York Times.

- ^ Steve Carney (January 20, 2012). "Geraldo Rivera to debut radio talk show on KABC-AM". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Fox News Segment of Geraldo Rivera's Comments Regarding Trayvon Martin's Death on YouTube

- ^ Lee, MJ (March 23, 2012). "Geraldo Rivera: My own son ashamed of me". Politico. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (March 27, 2012). "Geraldo undoes apology!". The Washington Post.

- ^ Simmons, Russell (March 27, 2012). "Geraldo, Your Apology Is Bullsh*t!". Global Grind.

- ^ Geraldo Rivera's Apology on YouTube

- ^ "Twitter". Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Stetler, Brian (February 4, 2013). "Fox News Monitors Geraldo as He Mulls Political Office". The NY Times.

- ^ Adams, T. Becket (November 13, 2015). "Geraldo Rivera's daughter in Paris during terror attack". Washington Examiner. Retrieved November 14, 2015.

- ^ "'Dancing With the Stars' 2016: Season 22 Celebrity Cast Revealed Live on 'GMA'". ABC News. March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ^ "'Dancing with the Stars' Recap: Latin Night and the First Elimination". buddytv.com. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ McDougal, Dennis (March 5, 1989). "There's a New Geraldo...Sort of : Rivera' still a TV outlaw, but he's moving into new corporate, personal and professional worlds". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Froelich, Janis D.. (July 15, 1991) Geraldo . . . Er, Make That Gerald Rivera's Moms Tell All!. Deseret News. Retrieved on December 17, 2011.

- ^ Geraldo, wife overcome fertility foes, have baby. Herald-Journal. November 9, 1992

- ^ 50 Highs and Lows from 40 Years in the News Business. Geraldo.com (September 5, 2010). Retrieved on December 17, 2011.

- ^ via Associated Press. "Geraldo Rivera sues over housing dispute", USA Today, September 13, 2004. Accessed March 17, 2011. "The Fox News senior correspondent owns two homes in the 26-acre Edgewater Colony, where residents own their homes but share ownership of the land.... 'I intend living here always, hopefully in peace and loving my neighbors.'"

- ^ Cheslow, Jerry. "If You're Thinking of Living In: Middletown Township, N.J.;A Historic Community on Raritan Bay", The New York Times, December 24, 1995. Accessed May 10, 2007. "The most expensive area is along the Shrewsbury River, where an eight-bedroom colonial on five acres is listed at $5.9 million. Among the residents of that area are Geraldo Rivera, the television personality, and members of the Hovnanian home-building family."

- ^ "Race Archives". Marionbermuda.com.

- ^ "IMDB Sail To The Century". imdb.com.

- ^ "Geraldo Rivera: Sail To The Century". geraldo.com.

External links

- Official website

- "Geraldo Rivera Official Statement Regarding Embedment Controversy", 4 April 2003 at the Wayback Machine (archived November 20, 2006) – Rivera tells the story of his Iraq "Map in the Sand"

- "Pentagon Says Geraldo Rivera Will Be Removed From Iraq" – The New York Times, April 1, 2003

- Geraldo Rivera's Influence on the Satanic Ritual Abuse and Recovered Memory Hoaxes – from religioustolerance.org

- Urban Legend about Geraldo Rivera's name being changed from Jerry Rivers – from snopes.com

- Geraldo Rivera at IMDb

- Geraldo Rivera at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1943 births

- 20th-century American writers

- 21st-century American writers

- American journalists of Puerto Rican descent

- American male writers

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American political writers

- American radio personalities

- American Reform Jews

- American television reporters and correspondents

- American television talk show hosts

- Brooklyn Law School alumni

- CNBC people

- American conspiracy theorists

- Fox News Channel people

- Jewish American writers

- Journalists from New Jersey

- Journalists from New York City

- Living people

- New Jersey lawyers

- New York lawyers

- New Jersey Republicans

- New York Republicans

- Peabody Award winners

- People from Edgewater, New Jersey

- People from Middletown Township, New Jersey

- People from West Babylon, New York

- University of Arizona alumni

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from New Jersey

- Writers from New York City

- Participants in American reality television series

- American journalists of Jewish descent