Greek numerals

| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Greek numerals is a system of representing numbers using the letters of the Greek alphabet. These alphabetic numerals are also known by names Ionic or Ionian numerals, Milesian numerals, and Alexandrian numerals. In modern Greece, they are still used for ordinal numbers and in situations similar to those in which Roman numerals are still used elsewhere in the West. For ordinary cardinal numbers, however, Greece uses Arabic numerals.

History

The Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations' Linear A and Linear B alphabets used a different system, called Aegean numerals, which included specialized symbols for numbers: 𐄇 = 1, 𐄐 = 10, 𐄙 = 100, 𐄢 = 1000, and 𐄫 = 10000.[1]

Attic numerals, which were later adopted as the basis for Roman numerals, were the first alphabetic set. They were acrophonic, derived (after the initial one) from the first letters of the names of the numbers represented. They ran ![]() = 1,

= 1, ![]() = 5,

= 5, ![]() = 10,

= 10, ![]() = 100,

= 100, ![]() = 1000, and

= 1000, and ![]() = 10000. 50, 500, 5000, and 50000 were represented by the letter

= 10000. 50, 500, 5000, and 50000 were represented by the letter ![]() with minuscule powers of ten written in the top right corner:

with minuscule powers of ten written in the top right corner: ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .[1] The same system was used outside of Attica, but the symbols varied with the local alphabets: in Boeotia,

.[1] The same system was used outside of Attica, but the symbols varied with the local alphabets: in Boeotia, ![]() was 1000.[2]

was 1000.[2]

The present system probably developed around Miletus in Ionia. 19th-century classicists placed its development in the 3rd century BC, the occasion of its first widespread use.[3] More thorough modern archaeology has caused the date to be pushed back at least to the 5th century BC,[4] a little before Athens abandoned its pre-Euclidean alphabet in favor of Miletus's in 402 BC, and it may predate that by a century or two.[5] The present system uses the 24 letters adopted by Euclid as well as three Phoenician and Ionic ones that were not carried over: digamma, koppa, and sampi. The position of those characters within the numbering system imply that the first two were still in use (or at least remembered as letters) while the third was not. The exact dating, particularly for sampi, is problematic since its uncommon value means the first attested representative near Miletus does not appear until the 2nd century BC[6] and its use is unattested in Athens until the 2nd century AD.[7] (In general, Athens resisted the use of the new numerals for the longest of any of the Greek states but had fully adopted them by AD c. 50.[2])

Description

Greek numerals are decimal, based on powers of 10. The units from 1 to 9 are assigned to the first nine letters of the old Ionic alphabet from alpha to theta. Instead of reusing these numbers to form multiples of the higher powers of ten, however, each multiple of ten from 10 to 90 was assigned its own separate letter from the next nine letters of the Ionic alphabet from iota to koppa. Each multiple of one hundred from 100 to 900 was then assigned its own separate letter as well, from rho to sampi.[8] (The fact that this was not the traditional location of sampi or its possible predecessor san has led classicists to conclude that it was no longer in use even locally by the time the system was created.)

This alphabetic system operates on the additive principle in which the numeric values of the letters are added together to obtain the total. For example, 241 was represented as ![]()

![]()

![]() (200 + 40 + 1). (It was not always the case that the numbers ran from highest to lowest: a 4th-century BC inscription at Athens placed the units to the left of the tens. This practice continued in Asia Minor well into the Roman period.[2]) In ancient and medieval manuscripts, these numerals were eventually distinguished from letters using overbars: α, β, γ, etc. In medieval manuscripts of the Book of Revelation, the number of the Beast 666 is written as χξς (600 + 60 + 6). (Numbers larger than 1,000 reused the same letters but included various marks to note the change.)

(200 + 40 + 1). (It was not always the case that the numbers ran from highest to lowest: a 4th-century BC inscription at Athens placed the units to the left of the tens. This practice continued in Asia Minor well into the Roman period.[2]) In ancient and medieval manuscripts, these numerals were eventually distinguished from letters using overbars: α, β, γ, etc. In medieval manuscripts of the Book of Revelation, the number of the Beast 666 is written as χξς (600 + 60 + 6). (Numbers larger than 1,000 reused the same letters but included various marks to note the change.)

Although the Greek alphabet began with only majuscule forms, surviving papyrus manuscripts from Egypt show that uncial and cursive minuscule forms began early. These new letter forms sometimes replaced the former ones, especially in the case of the obscure numerals. The old Q-shaped koppa (Ϙ) began to be broken up (![]() and

and ![]() ) and simplified (

) and simplified (![]() and

and ![]() ). The numeral for 6 changed several times. During antiquity, the original letter form of digamma (

). The numeral for 6 changed several times. During antiquity, the original letter form of digamma (![]() ) came to be avoided in favor of a special numerical one (

) came to be avoided in favor of a special numerical one (![]() ). By the Byzantine era, the letter was known as episemon and written as

). By the Byzantine era, the letter was known as episemon and written as ![]() or

or ![]() . This eventually merged with the sigma-tau ligature stigma (

. This eventually merged with the sigma-tau ligature stigma (![]() or

or ![]() ).

).

In modern Greek, a number of other changes have been made. Instead of extending an overbar over an entire number, the keraia (κεραία, lit. "hornlike projection") is marked to its upper right, a development of the short marks formerly used for single numbers and fractions. The modern keraia is a symbol (ʹ) similar the acute accent (´) but has its own Unicode character as U+0374. Alexander the Great's father Philip II of Macedon is thus known as Φίλιππος Βʹ in modern Greek. A lower left keraia (Unicode: U+0375, "Greek Lower Numeral Sign") is now standard for distinguishing thousands: 2015 is represented as ͵ΒΙΕʹ (2000 + 10 + 5).

The declining use of ligatures in the 20th century also means that stigma is frequently written as the separate letters ΣΤʹ, although a single keraia is used for the group.[9]

The art of assigning Greek letters also being thought of as numerals and therefore giving words/names/phrases a numeric sum that has meaning through being connected to words/names/phrases of similar sum is called isopsephy (gematria).

Table

| Ancient | Byzantine | Modern | Value | Ancient | Byzantine | Modern | Value | Ancient | Byzantine | Modern | Value | Ancient | Byzantine | Modern | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | Αʹ | 1 | ι | Ιʹ | 10 | ρ | Ρʹ | 100 | ͵α | ͵Α | 1000 | |||||||

| β | Βʹ | 2 | κ | Κʹ | 20 | σ | Σʹ | 200 | ͵β | ͵Β | 2000 | |||||||

| γ | Γʹ | 3 | λ | Λʹ | 30 | τ | Τʹ | 300 | ͵ |

͵Γ | 3000 | |||||||

| δ | Δʹ | 4 | μ | Μʹ | 40 | υ | Υʹ | 400 | ͵ |

͵Δ | 4000 | |||||||

| ε | Εʹ | 5 | ν | Νʹ | 50 | φ | Φʹ | 500 | ͵ε | ͵Ε | 5000 | |||||||

| Ϛʹ ΣΤʹ |

6 | ξ | Ξʹ | 60 | χ | Χʹ | 600 | ͵ ͵ |

͵Ϛ | 6000 | ||||||||

| ζ | Ζʹ | 7 | ο | Οʹ | 70 | ψ | Ψʹ | 700 | ͵ζ | ͵Z | 7000 | |||||||

| η | Ηʹ | 8 | π | Πʹ | 80 | ω | Ωʹ | 800 | ͵η | ͵H | 8000 | |||||||

| θ | Θʹ | 9 | Ϟʹ | 90 | Ϡʹ | 900 | ͵θ | ͵Θ | 9000 |

- Alternatively, sub-sections of manuscripts are sometimes numbered {1,2,3,...,9} by lowercase characters {αʹ. βʹ. γʹ. δʹ. εʹ. ϛʹ. ζʹ. ηʹ. θʹ.}

- In Ancient Greek, Myriad notation is used for numbers larger than 9,999, e.g. ͵εωοεʹ for 1,755,875.

Higher numbers

In his text The Sand Reckoner, the natural philosopher Archimedes gives an upper bound of the number of grains of sand required to fill the entire universe, using a contemporary estimation of its size. This would defy the then-held notion that it is impossible to name a number greater than that of the sand on a beach or on the entire world. In order to do that, he had to devise a new numeral scheme with much greater range.

Zero

Hellenistic astronomers extended alphabetic Greek numerals into a sexagesimal positional numbering system by limiting each position to a maximum value of 50 + 9 and including a special symbol for zero, which was also used alone like today's modern zero, more than as a simple placeholder. However, the positions were usually limited to the fractional part of a number (called minutes, seconds, thirds, fourths, etc.) — they were not used for the integral part of a number. This system was probably adapted from Babylonian numerals by Hipparchus c. 140 BC. It was then used by Ptolemy (c. 140), Theon (c. 380) and Theon's daughter Hypatia (murdered 415).

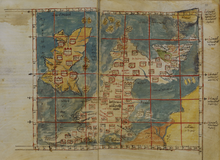

In Ptolemy's table of chords, the first fairly extensive trigonometric table, there were 360 rows, portions of which looked as follows:

Each number in the first column, labeled περιφερειῶν, is the number of degrees of arc on a circle. Each number in the second column, labeled ευθειῶν, is the length of the corresponding chord of the circle, when the diameter is 120. Thus πδ represents an 84° arc, and the ∠' after it means one-half, so that πδ∠' means 84.5°. In the next column we see π μα γ, meaning 80 + 41/60 + 3/602. That is the length of the chord corresponding to an arc of 84.5° when the diameter of the circle is 120. The next column, labeled ὲξηκοστῶν, for "sixtieths", is the number to be added to the chord length for each 1° increase in the arc, over the span of the next 12°. Thus that last column was used for linear interpolation.

The Greek sexagesimal placeholder or zero symbol changed over time. The symbol used on papyri during the second century was a very small circle with an overbar several diameters long, terminated or not at both ends in various ways. Later, the overbar shortened to only one diameter, similar to the modern o macron (ō) which was still being used in late medieval Arabic manuscripts whenever alphabetic numerals were used. But the overbar was omitted in Byzantine manuscripts, leaving a bare ο (omicron). This gradual change from an invented symbol to ο does not support the hypothesis that the latter was the initial of ουδέν meaning "nothing".[10][11] Note that the letter ο was still used with its original numerical value of 70; however, there was no ambiguity, as 70 could not appear in the fractional part of a number, and zero was usually omitted when it was the integer.

Some of Ptolemy's true zeros appeared in the first line of each of his eclipse tables, where they were a measure of the angular separation between the center of the Moon and either the center of the Sun (for solar eclipses) or the center of Earth's shadow (for lunar eclipses). All of these zeros took the form 0 | 0 0, where Ptolemy actually used three of the symbols described in the previous paragraph. The vertical bar (|) indicates that the integral part on the left was in a separate column labeled in the headings of his tables as digits (of five arc-minutes each), whereas the fractional part was in the next column labeled minute of immersion, meaning sixtieths (and thirty-six-hundredths) of a digit.[12]

See also

- Attic numerals

- Gematria

- Greek numerals in Unicode (acrophonic, not alphabetic, numerals)

- Isopsephy

- Number of the Beast

References

- ^ a b Samuel Verdan (20 Mar 2007). "Systèmes numéraux en Grèce ancienne: description et mise en perspective historique" (in French). Retrieved 2 Mar 2011.

- ^ a b c Heath, Thomas L. A Manual of Greek Mathematics, pp. 14 ff. Oxford Univ. Press (Oxford), 1931. Reprinted Dover (Mineola), 2003. Accessed 1 November 2013.

- ^ Thompson, Edward M. Handbook of Greek and Latin Palaeography, p. 114. D. Appleton (New York), 1893.

- ^ The Packard Humanities Institute (Cornell & Ohio State Universities). Searchable Greek Inscriptions: "IG I³ 1387" [also known as IG I² 760]. Accessed 1 November 2013.

- ^ Jeffery, Lilian H. The Local Scripts of Archaic Greece, pp. 38 ff. Clarendon (Oxford), 1961.

- ^ The Packard Humanities Institute (Cornell & Ohio State Universities). Searchable Greek Inscriptions: "Magnesia 4" [also known as Syll³ 695.b]. Accessed 1 November 2013.

- ^ The Packard Humanities Institute (Cornell & Ohio State Universities). Searchable Greek Inscriptions: "IG II² 2776". Accessed 1 November 2013.

- ^ Edkins, Jo (2006). "Classical Greek Numbers". Retrieved 29 Apr 2013.

- ^ Nick Nicholas (9 Apr 2005). "Numerals: Stigma, Koppa, Sampi". Retrieved 2 Mar 2011.

- ^ Neugebauer, Otto (1969) [1957]. The Exact Sciences in Antiquity (2 ed.). Dover Publications. pp. 13–14, plate 2. ISBN 978-0-486-22332-2.

- ^ Raymond Mercier, "Consideration of the Greek symbol 'zero'" (PDF). (1.32 MiB) Numerous examples

- ^ Ptolemy's Almagest, translated by G. J. Toomer, Book VI, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), pp. 306–7.