Jain cosmology

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Jain cosmology is the description of the shape and functioning of the Universe (loka) and its constituents (such as living beings, matter, space, time etc.) according to Jainism. Jain cosmology considers the universe, as an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, having neither beginning nor end.[1] Jain texts describe the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom.[2]

Six eternal substances

According to Jains, the Universe is made up of six simple and eternal substances called dravya classified as follows:

- Jīva (Living Substances)

- Jīva (Jainism)|Jīva i.e. Souls - Jīva exists as a reality, having a separate existence from the body that houses it. It is characterised by chetana (consciousness) and upayoga (knowledge and perception).[3] Though the soul experiences both birth and death, it is neither really destroyed nor created. Decay and origin refer respectively to the disappearing of one state of soul and appearing of another state, these being merely the modes of the soul.[4]

- Ajīva (Non-Living Substances)

- Pudgala (Matter) - Matter is classified as solid, liquid, gaseous, energy, fine Karmic materials and extra-fine matter i.e. ultimate particles. Paramāṇu or ultimate particle is the basic building block of all matter. The Paramāṇu and Pudgala are permanent and indestructible. Matter combines and changes its modes but its basic qualities remain the same. According to Jainism, it cannot be created, nor destroyed.

- Dharma-dravya (Principle of Motion) and

- Adharma-dravya (Principle of Rest) - Dharmastikāya and Adharmastikāya are distinctly peculiar to Jaina system of thought depicting the principle of Motion and Rest. They are said to pervade the entire universe. Dharma and Adharma are by itself not motion or rest but mediate motion and rest in other bodies. Without Dharmastikāya motion is not possible and without Adharmastikāya rest is not possible in the universe.

- Ākāśa (Space) - Space is a substance that accommodates the living souls, the matter, the principle of motion, the principle of rest and time. It is all-pervading, infinite and made of infinite space-points.

- Kāla (Time) - Kāla is an eternal substance according to Jainism and all activities, changes or modifications can be achieved only through the progress of time. According to the Jain text, Dravyasaṃgraha:

Conventional time (vyavahāra kāla) is perceived by the senses through the transformations and modifications of substances. Real time (niścaya kāla), however, is the cause of imperceptible, minute changes (called vartanā) that go on incessantly in all substances.

— Dravyasaṃgraha (21)[5]

Universe and its structure

The Jain doctrine postulates an eternal and ever-existing world which works on universal natural laws. The existence of a creator deity is overwhelmingly opposed in the Jain doctrine. Mahāpurāṇa, a Jain text authored by Ācārya Jinasena is famous for this quote:

Some foolish men declare that a creator made the world. The doctrine that the world was created is ill advised and should be rejected. If God created the world, where was he before the creation? If you say he was transcendent then and needed no support, where is he now? How could God have made this world without any raw material? If you say that he made this first, and then the world, you are faced with an endless regression.

According to Jains, the universe has a firm and an unalterable shape which is measured in the Jain texts by means of a unit called Rajju which is supposed to be very large. The Digambara sect of Jainism postulates that the universe is fourteen Rajju high and extends seven Rajjus from north to south. Its breadth is seven Rajjus at the bottom and decreases gradually till the middle where it is one Rajju. The width then increases gradually till it is five Rajju and again decreases till it is one Rajju. The apex of the universe is one Rajju long, one Rajju wide and eight Rajju high. The total space of the world is thus 343 cubic Rajju. The svetambara view differs slightly and postulates that there is constant increase and decrease in the breadth and the space is 239 cubic Rajju. Apart from the apex which is the abode of liberated beings, the universe is divided into three parts. The world is surrounded by three atmospheres: dense-water, dense-wind and thin-wind. It is then surrounded by infinitely large non-world which is absolutely empty.

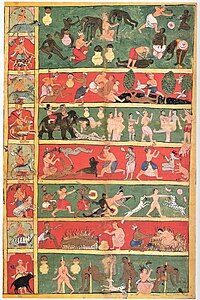

The whole world is said to be filled with living beings. In all the three parts, there is the existence of very small living beings called nigoda. Nigoda are of two types: nitya-nigoda and Itara-nigoda. Nitya-nigoda are those which will reborn as nigoda throughout eternity where as Itara-nigoda will be reborn as other beings too. The mobile region of universe (Trasandi) is one Rajju wide, one Rajju broad and fourteen Rajju high. Within this, there are animals and plants everywhere where as Human beings are restricted to 2.5 continents of middle world. The beings inhabiting lower world are called Naraki (Hellish beings). Deva (roughly demi-gods) live in whole of the top and middle world and top three realms of lower world. Living beings are divided in fourteen classes (Jivasthana) : 1. fine beings with one sense. 2. Crude beings with one sense. 3. beings with two sense. 4. beings with three sense. 5. Beings with four sense. 6. beings with five sense without mind. 7. beings with five sense with a mind. These can be under-developed or developed which makes it a total of fourteen. Human beings get any form of existence and are the only ones which can attain salvation.

Three lokas

The early Jains contemplated the nature of the earth and universe and developed a detailed hypothesis on the various aspects of astronomy and cosmology. According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into 3 parts:[6]

- Urdhva Loka – the realms of the gods or heavens

- Madhya Loka – the realms of the humans, animals and plants

- Adho Loka – the realms of the hellish beings or the infernal regions

The following Upanga āgamas describe the Jain cosmology and geography in a great detail:[6]

- Sūryaprajñapti – Treatise on Sun

- Jambūdvīpaprajñapti - Treatise on the island of Roseapple tree; it contains a description of Jambūdvī and life biographies of Ṛṣabha and King Bharata

- Candraprajñapti - Treatise on moon

Additionally, the following texts describe the Jain cosmology and related topics in detail:

- Trilokasāra – Essence of the three worlds (heavens, middle level, hells)

- Trilokaprajñapti – Treatise on the three worlds

- Trilokadipikā – Illumination of the three worlds

- Tattvārthasūtra - Description on nature of realities

- Kṣetrasamasa – Summary of Jain geography

- Bruhatsamgrahni – Treatise on Jain cosmology and geography

Urdhva Loka, the upper world

Upper World (Udharva loka) is divided into different abodes and are the realms of the heavenly beings (demi-gods) who are non-liberated souls.

Upper World is divided into sixteen Devalokas, nine Graiveyaka, nine Anudish and five Anuttar abodes. Sixteen Devaloka abodes are Saudharma, Aishana, Sanatkumara, Mahendra, Brahma, Brahmottara, Lantava, Kapishta, Shukra, Mahashukra, Shatara, Sahasrara, Anata, Pranata, Arana and Achyuta. Nine Graiveyak abodes are Sudarshan, Amogh, Suprabuddha, Yashodhar, Subhadra, Suvishal, Sumanas, Saumanas and Pritikar. Nine Anudish are Aditya, Archi, Archimalini, Vair, Vairochan, Saum, Saumrup, Ark and Sphatik. Five Anuttar are Vijaya, Vaijayanta, Jayanta, Aparajita and Sarvarthasiddhi.

The sixteen heavens in Devalokas are also called Kalpas and the rest are called Kalpatit. Those living in Kalpatit are called Ahamindra and are equal in grandeur. There is increase with regard to the lifetime, influence of power, happiness, lumination of body, purity in thought-colouration, capacity of the senses and range of clairvoyance in the Heavenly beings residing in the higher abodes. But there is decrease with regard to motion, stature, attachment and pride. The higher groups, dwelling in 9 Greveyak and 5 Anutar Viman. They are independent and dwelling in their own vehicles. The anuttara souls attain liberation within one or two lifetimes. The lower groups, organized like earthly kingdoms - rulers (Indra), counselors, guards, queens, followers, armies etc.

Above the Anutar vimans, at the apex of the universe, is the Siddhasila, the realms of the liberated souls also known as the Siddhas, the perfected omniscient and blissful beings, who are venerated by the Jains.[7]

Madhya Loka, the middle world

Madhya Loka, at the centre of the universe consists of 900 yojans above and 900 yojans below earth surface. It is inhabited by:[7]

- Jyotishka devas (luminous gods) - 790 to 900 yojans above earth

- Humans,[8] Tiryanch (Animals, birds, plants) on the surface

- Vyantar devas (Intermediary gods)- 100 yojan below the ground level

Madhyaloka consists of many continent-islands surrounded by oceans, first eight whose names are:

Continent/ Island Ocean Jambūdvīpa Lavanoda (Salt - ocean) Ghatki Khand Kaloda (Black sea) Puskarvardvīpa Puskaroda (Lotus Ocean) Varunvardvīpa Varunoda (Varun Ocean) Kshirvardvīpa Kshiroda (Ocean of milk) Ghrutvardvīpa Ghrutoda (Butter milk ocean) Ikshuvardvīpa Iksuvaroda (Sugar Ocean) Nandishwardvīpa Nandishwaroda

Mount Meru (also Sumeru) is at the centre of the world surrounded by Jambūdvīpa,[8] in form of a circle forming a diameter of 100,000 yojans.[7] There are two sets of sun, moon and stars revolving around Mount Meru; while one set works, the other set rests behind the Mount Meru.[9][10][11]

Jambūdvīpa continent has 6 mighty mountains, dividing the continent into 7 zones (Ksetra). The names of these zones are:

- Bharat Kshetra

- Mahavideh Kshetra

- Airavat Kshetra

- Ramyak

- Hairanyvat Kshetra

- Haimava Kshetra

- Hari Kshetra

The three zones i.e. Bharat Kshetra, Mahavideh Kshetra and Airavat Kshetra are also known as Karma bhoomi because practice of austerities and liberation is possible and the Tirthankaras preach the Jain doctrine.[12] The other four zones, Ramyak, Hairanyvat Kshetra, Haimava Kshetra and Hari Kshetra are known as akarmabhoomi or bhogbhumi as humans live a sinless life of pleasure and no religion or liberation is possible.

Nandishvara Dvipa is not the edge of cosmos, but it is beyond the reach of humans.[8] Humans can reside only on Jambudvipa, Dhatatikhanda Dvipa, and the inner half of Pushkara Dvipa.[8]

Adho Loka, the lower world

The lower world consists of seven hells, which are inhabited by Bhavanpati demigods and the hellish beings. Hellish beings reside in the following hells -

- Ratna prabha-dharma.

- Sharkara prabha-vansha.

- Valuka prabha-megha.

- Pank prabha-anjana.

- Dhum prabha-arista.

- Tamah prabha-maghavi.

- Mahatamah prabha-maadhavi

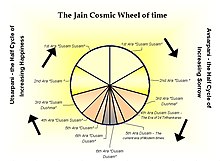

Time cycle

According to Jainism, time is beginningless and eternal.[13] The Kālacakra, the cosmic wheel of time, rotates ceaselessly. The wheel of time is divided into two half-rotations, Utsarpiṇī or ascending time cycle and Avasarpiṇī, the descending time cycle, occurring continuously after each other.[14][15] Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity and happiness where the time spans and ages are at an increasing scale, while Avsarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality with decline in timespans of the epochs. Each of this half time cycle consisting of innumerable period of time (measured in sagaropama and palyopama years)[note 1] is further sub-divided into six aras or epochs of unequal periods. Currently, the time cycle is in avasarpiṇī or descending phase with the following epochs.[16]

| Name of the Ara | Degree of happiness | Duration of Ara | Maximum height of people | Maximum lifespan of people |

| Suṣama-suṣamā | Utmost happiness and no sorrow | 400 trillion sāgaropamas | Six miles tall | Three Palyopam years |

| Suṣamā | Moderate happiness and no sorrow | 300 trillion sāgaropamas | Four miles tall | Two Palyopam Years |

| Suṣama-duḥṣamā | Happiness with very little sorrow | 200 trillion sāgaropamas | Two miles tall | One Palyopam Years |

| Duḥṣama-suṣamā | Happiness with little sorrow | 100 trillion sāgaropamas | 1500 meters | 84 Lakh Purva |

| Duḥṣamā | Sorrow with very little happiness | 21,000 years | 7 hatha | 120 years |

| Duḥṣama- duḥṣamā | Extreme sorrow and misery | 21,000 years | 1 hatha | 20 years |

- Suṣama-suṣamā (read as Sukhma-sukhma) - During the first ara of the Avsarpini, people lived for three palyopama years. During this ara people were on average six miles tall. They took their food on every fourth day; they were very tall and devoid of anger, pride, deceit, greed and other sinful acts. Various kinds of the kalpavriksha fulfilled their wishes and needs like food, clothing, homes, entertainment, jewels etc.

- Suṣamā (read as Sukhma) - During the second ara the people lived for two palyopama years. During this ara people were on average 4 miles tall. They took their food at an interval of three days, but the kalpavriksha supplied their wants, less than before. The land and water became less sweet and fruitful than they were during the first ara.

- Suṣama-duḥṣamā (read as Sukhma-dukhma) - During the third ara, the age limit of the people became one palyopama year. During this are people were on average 2 miles tall. They took their food on every second day. The earth and water as well as height and strength of the body went on decreasing and they became less than they were during the second ara. The first three ara the children were born as twins, one male and one female, who married each other and once again gave birth to twins. On account of happiness and pleasures, the religion, renunciation and austerities was not possible. At the end of the third ara, the wish-fulfilling trees stopped giving the desired fruits and the people started living in the societies. The first Tirthankara, Rishabhanatha was born at the end of this ara. He taught the people the skills of farming, commerce, defence, politics and arts (intotal 72 arts for men and 64 arts for women) and organised the people in societies. That is why he is known as the father of human civilisation.

- Duḥṣama-suṣamā (read as Dukhma-sukhma) - During the fourth ara, people lived for 705.6 Quintillion Years. During this are people were on average 1500 Meters tall. The fourth ara was the age of religion, where the renunciation, austerities and liberation was possible. The 63 Śalākāpuruṣas, or the illustrious persons who promote the Jain religion, regularly appear in this ara. The balance 23 Tīrthaṅkars, including Lord Māhavīra appeared in this ara. This ara came to an end 3 years and 8 months after the nirvāṇa of Māhavīra.

- Duṣama (read as Dukhma) - According to Jain texts, currently we are in the 5th ara. As of 2016, exactly 2,540 years have elapsed and 18,460 years are still left.[17] It is an age of sorrow and misery. The maximum age a person can live to in this ara is not more than 125 years. The average height of people in this ara is six feet tall. No liberation is possible, although people practice religion in lax and diluted form. At the end of this ara, even the Jain religion will disappear,[17] only to appear again with the advent of 1st Tirthankara in the next cycle.

- Duṣama - duṣama (read as Dukhma-dukhma)- The sixth ara will be the age of intense misery and sorrow, making it impossible to practice religion in any form. The age, height and strength of the human beings will decrease to a great extent. In this era people will live for no more than 16–20 years. This trend will start reversing at the onset of utsarpiṇī kāl.

In utsarpiṇī the order of the eras is reversed. Starting from Duḥṣama- duḥṣamā, it ends with Suṣama-suṣamā and thus this never ending cycle continues.[18] Each of these aras progress into the next phase seamlessly without any apocalyptic consequences. The increase or decrease in the happiness, life spans and length of people and general moral conduct of the society changes in a phased and graded manner as the time passes. No divine or supernatural beings are credited or responsible with these spontaneous temporal changes, either in a creative or overseeing role, rather human beings and creatures are born under the impulse of their own karmas.[19]

Śalākāpuruṣas - The deeds of the 63 Illustrious Men

During each motion of the half-cycle of the wheel of time, 63 Śalākāpuruṣa or 63 illustrious men, consisting of the 24 Tīrthaṅkaras and their contemporaries regularly appear.[15] The Jain universal or legendary history is basically a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious men. They are categorised as follows:[20]

- 24 Tīrthaṅkaras – The 24 Tīrthaṅkaras or the ford makers appear in succession to activate the true religion and establish the community of ascetics and laymen.

- 12 Chakravartis – The Chakravartīs are the universal monarchs who rule over the six continents.

- 9 Balabhadras who lead an ideal Jain life.[21]

- 9 Narayana or Vasudev (heroes)

- 9 Prati-Naryana or Prati-Vasudev (anti-heroes) – They are anti-heroes who are ultimately killed by the Narayana.

Balabhadra and Narayana are half brothers who jointly rule over three continents.

Besides these a few other important classes of 106 persons are recognized:-

- 9 Naradas.

- 11 Rudras.

- 24 Kamdevas.

- 24 Fathers of the Tirthankaras.

- 24 Mothers of the Tirthankaras.

- 14 Kulakara (patriarchs)

See also

Notes

- ^ As per the Jain cosmology Sirsapahelika is the highest measurable number in Jainism which is 10^194 years. Higher than that is palyopama (pit measured years) which is explained by an analogy of a pit. Accordingly, a hollow pit of 8 x 8 x 8 miles tightly filled with hair particles of seven day old newly born. [A single hair form the above cut into eight pieces seven times = 20,97,152 Particles]. 1 Particle emptied after every 100 years, the time taken to empty the whole pit = 1 palyopama. (1 palyopama = countless years.) Hence palyopama is at least 10^194 years. Sagrapoma is 10 quadrillion palyopama, that means a Sagrapoma is more than 10^210 Years

Citations

- ^ "This universe is not created nor sustained by anyone; It is self sustaining, without any base or support" "Nishpaadito Na Kenaapi Na Dhritah Kenachichch Sah Swayamsiddho Niradhaaro Gagane Kimtvavasthitah" [Yogaśāstra of Ācārya Hemacandra 4.106] Tr by Dr. A. S. Gopani

- ^ See Hemacandras description of universe in Yogaśāstra "…Think of this loka as similar to man standing akimbo…"4.103-6

- ^ Ācārya Kundakunda, Pañcāstikāyasāra, Gatha 16

- ^ Ācārya Kundakunda, Pañcāstikāyasāra, Gatha 18

- ^ Jain 2013, p. 74.

- ^ a b Shah, Natubhai (1998). p. 25

- ^ a b c Schubring, Walther (1995), pp. 204–246

- ^ a b c d Cort 2010, p. 90.

- ^ CIL, "Indian Cosmology Reflections in Religion and Metaphysics", Ignca.nic.in

- ^ http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~pluralsm/affiliates/jainism/workshop/Jain%20Geoghaph.PDF

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal - Asiatic Society of Bengal, 1834

- ^ von Glasenapp 1999, p. 286.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 20.

- ^ a b Jaini 1998.

- ^ von Glasenapp 1999, pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b Dundas 2002, p. 13.

- ^ von Glasenapp 1999, p. 272.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Joseph, P. M. (1997), Jainism in South India, p. 178, ISBN 9788185692234

- ^ Jain, Jagdish Chandra; Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath (1 January 1994). Jainism and Prakrit in Ancient and Medieval India. p. 146. ISBN 9788173040511.

Sources

- Jain, Vijay K. (2013), Ācārya Nemichandra's Dravyasaṃgraha, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 9788190363952,

Non-copyright

- Nayanar, Prof. A. Chakravarti (2005), Pañcāstikāyasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda, New Delhi: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher, ISBN 81-7019-436-9

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1376-6

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Shah, Natubhai (1998), Jainism: The World of Conquerors, Volume I and II, Sussex: Sussex Academy Press, ISBN 1-898723-30-3

- Schubring, Walther (1995), "Cosmography", in (ed.) Wolfgang Beurlen (ed.), The Doctrine of the Jainas, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0933-5

{{citation}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Gopani, A. S.; Surendra Bothara ed. (1989), Yogaśāstra (Sanskrit) of Ācārya Hemacandra, Jaipur: Prakrit Bharti Academy

{{citation}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Cort, John (2010) [1953], Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1