Karelians

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 60,815 (2010)[3] | |

| 10,000 (1994)[4] | |

| 1,522 (2001)[5] | |

| 524 (1999)[6] | |

| 363 (2011)[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Karelian, Finnish, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity Lutheran (minority) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Baltic Finns | |

The Karelians, sometimes also Karels, East Karelians or Russian Karelians (Template:Lang-krl) are a Baltic-Finnic ethnic group living mostly in the Republic of Karelia and in other north-western parts of the Russian Federation. The historic homeland of the Karelians includes also parts of present-day Eastern Finland (North Karelia) and the formerly Finnish territory of Ladoga Karelia. In a process starting during the 17th century and culminating after the Second World War, the ethnic Karelians in Finland have been linguistically and ethnically assimilated with the closely related Finnish people and are included in the wider group of Finnish Karelians,[8] who are considered to form a sub-group of the ethnic Finns.

The separation between the Finnish Karelians and the East or Russian Karelians has been created and maintained by different religions, dialects and historical experiences.[9] The Karelians in Russia have lived for centuries under the Slavic cultural influence, adopted the Russian Orthodox religion, although not truly assimilated by Russians.[10][11][12]

Over the centuries the Karelians living in Russia have become dispersed in several distinct subgroups. The largest groups are North Karelians living in the Republic of Karelia and the South Karelians in the Tver, Novgorod and in the Leningrad Oblast of Russian federation. The subgroups of South Karelians, the Tikhvin Karels and Valdai Karels numbered between 90,000-100,000 are considered assimilated and speak Russian as their first language. The North Karelians include the Olonets and the Ludes, speakers of Olonets Karelian language and Ludic language live in the Russian Republic of Karelia.[13] According to 2010 census there were 60,815 Karelians in Russia.

History

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2008) |

The name Karelia first occurs in Scandinavian sources in the 8th century. In the mid-12th century Karelia and the Karelians are mentioned in Russian chronicles, referred to as Корела (Koryela), кореляне (koryelyanye). The Karelians are the original Baltic-Finnic tribe in the area between Lakes Ladoga and Onega. However, the Finns from Finnish Karelia have also been called Karelians, although they speak a Finnish dialect. The Izhorians are of the same origin as the Karelian people.[14]

Since the 13th century the Karelians have lived in the tension between the East and the West, between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism, later Lutheranism. Some Karelians were Christianized and subdued by Sweden, others by Novgorod or Russia. Thus Karelia was divided between two different and often hostile realms, and the Karelian population was split politically and religiously, after a while also linguistically and culturally.

The Kingdom of Sweden held Western Karelia and Karelian Isthmus but the so-called East Karelia was under the Russian rule. In 1617, the regions of Ladoga Karelia and North Karelia were annexed by Sweden. In the 17th century the tension between the Lutheran Swedish government and Orthodox Karelians triggered a mass migration from these areas into the region of Tver in Russia, forming the Tver Karelians minority. People from Savonia moved to Karelia in large numbers, and the present-day Finnish Karelians are largely their descendants. In 1721, Russia reconquered Ladoga Karelia, joining it to the new Grand Duchy of Finland in 1812.

During the 19th century Finnish folklorists including Elias Lönnrot traveled to North, Central and Eastern Karelia to gather archaic folklore and epic poetry. The Orthodox Karelians in North Karelia and Russia were now seen as close brethren or even a sub-group of the Finns. The ideology of Karelianism inspired Finnish artists and researchers, who believed that the Orthodox Karelians had retained elements of an archaic, original Finnish culture which had disappeared from Finland.

When Finland gained its independence in 1917 only a small fraction of the Orthodox Karelians lived in the Finnish Karelia, and in three villages of Oulu province. This region was mainly populated by Finnish Karelians of Lutheran background. Finland lost most of this area to the Soviet Union in World War II, when over 400,000 people were evacuated over Finland's new border from the Karelian Isthmus, Ladoga Karelia and, to a lesser degree, from the main part of East Karelia that had been held by Finland 1941–1944. 55 000 Orthodox Karelians were included among the people Finland evacuated from Ladoga Karelia. These were mainly Karelian-speaking, but they and their descendants soon adopted the Finnish language after the war. Many of the evacuees have immigrated, mainly to Sweden, to Australia and to North America.

The Russian Karelians, living in the Republic of Karelia, are nowadays rapidly being absorbed into the Russian population. This process began several decades ago. For example, it has been estimated that even between the 1959 and 1970 Soviet censuses, nearly 30 percent of those who were enumerated as Karelian by self-identification in 1959 changed their self-identification to Russian 11 years later.[15]

Language

The Karelian language is closely related to the Finnish language, and particularly by Finnish linguists seen as a dialect of Finnish, although the variety spoken in East Karelia is usually seen as a distinct language.[16]

The dialect spoken in the South Karelian region of Finland belongs to the South Eastern dialects of the Finnish language. The dialect spoken in the Karelian Isthmus before World War II and the Ingrian dialect were also part of this dialect group. The dialect that is spoken in North Karelia is considered to be one of the Savonian dialects.[17]

Religion

The Russian Karelians are Eastern Orthodox Christians. Most Finnish Karelians are Lutherans.

Demographics

Significant enclaves of Karelians exist in the Tver oblast of Russia, resettled after Russia's defeat in 1617 against Sweden — in order to escape the peril of forced conversion to Lutheranism in Swedish Karelia. The Russians also promised tax deductions if the Orthodox Karelians migrated there. Olonets (Aunus) is the only city in Russia where the Karelians form a majority (60% of the population).

Karelians have been declining in numbers in modern times significantly due to a number of factors. These include low birthrates (characteristic of the region in general) and especially Russification, due to the predominance of Russian language and culture. In 1926, according to the census, Karelians only accounted for 37.4% of the population in the Soviet Karelian Republic (which at that time did not yet include territories that would later be taken from Finland and added, most of which had mostly Karelian inhabitants), or 0.1 million Karelians. Russians, meanwhile, numbered 153,967 in Karelia, or 57.2% of the population. By 2002, there were only 65,651 Karelians in the Republic of Karelia (65.1% of the number in 1926, including the Karelian regions taken from Finland which were not counted in 1926), and Karelians made up only 9.2% of the population in their homeland. Russians, meanwhile, were 76.6% of the population in Karelia. This trend continues to this day, and may cause the disappearance of Karelians as a distinct group.

Culture

The Karelian culture and language was a major inspiration for the Fennoman movement, and the unification of East Karelia with independent Finland (Greater Finland) was a major political issue in 20th century Finland.

See also

References

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7.

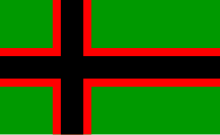

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Karelian flags

- ^ Russian census of 2010

- ^ Ethnologue report for language code: krl

- ^ Ethnic composition of Ukraine 2001

- ^ [1]

- ^ RL0428: Rahvastik rahvuse, soo ja elukoha järgi, 31. detsember 2011

- ^ Levinson, David (1991). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. G.K. Hall.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Karjalan kieltä ja murretta, in Finnish by Kotus, the Research Centre of Domestic Languages in Finland

- ^ Karjalan tulevaisuus, in Finnish ("The Future of Karelia") by Kotus

- ^ Taagepera, Rein (1999). The Finno-Ugric Republics and the Russian State. Routledge. pp. 100–146, Karelia Orthodox Finland. ISBN 978-0-415-91977-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Redbook, an Estonian site

- ^ Language Death and Language Maintenance. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2000. ISBN 978-90-272-4752-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The Peoples of the Red Book, The Karelians

- ^ Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, "Estimating Russification of Ethnic Identity among Non-Russians in the USSR," Demography 20 (November, 1983): 461-489.

- ^ [2]

- ^ http://www.kotus.fi/index.phtml?s=368

External links

- Russian Karelians (The Peoples of the Red Book)

- Saimaa Canal links two Karelias (ThisisFINLAND from Ministry for Foreign Affairs)

- Tracing Finland's Eastern Border(ThisisFINLAND from Ministry for Foreign Affairs)

- Finno-Ugric media center