Local government in the United States

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

Local government in the United States refers to governmental jurisdictions below the level of the state. Most states have at least two tiers of local government: counties and municipalities. In some states, counties are divided into townships. There are several different types of jurisdictions at the municipal level, including the city, town, borough, and village. The types and nature of these municipal entities varies from state to state.

Many rural areas and even some suburban areas of many states have no municipal government below the county level. In other places consolidated city–county jurisdictions exist, in which city and county functions are managed by a single municipal government. In some New England states, towns are the primary unit of local government and counties have no governmental function but exist in a purely perfunctory capacity (e.g. for census data).

In addition to general purpose local governments, there may be local or regional special-purpose local governments,[1] such as school districts and districts for fire protection, sanitary sewer service, public transportation, public libraries, or water resource management. Such special purpose districts often encompass areas in multiple municipalities. As of 2012, using the Census Bureau's definition, there were 89,055 local government units in the United States.[1]

History

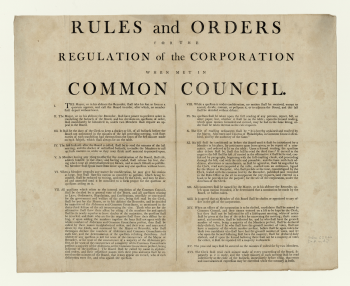

When America was settled by Europeans from the 17th century onward, there was initially little control from governments back in Europe.[2] Many settlements began as shareholder or stockholder business enterprises, and while the king of Britain had technical sovereignty, in most instances "full governmental authority was vested in the company itself."[2] Settlers had to fend for themselves; compact towns sprung up based as legal corporations in what has been described as "pure democracy":

The people, owing to the necessity of guarding against the Indians and wild animals, and to their desire to attend the same church, settled in small, compact communities, or townships, which they called towns. The town was a legal corporation, was the political unit, and was represented in the General Court. It was a democracy of the purest type. Several times a year the adult males met in town meeting to discuss public questions, to lay taxes, to make local laws, and to elect officers. The chief officers were the "selectmen," from three to nine in number, who should have the general management of the public business; the town clerk, treasurer, constables, assessors, and overseers of the poor. To this day the town government continues in a large measure in some parts of New England.––historian Henry William Elson writing in 1904.[3]

Propertied men voted; in no colonies was there universal suffrage.[4] The founding by a group of Puritans in 1629, led by John Winthrop came with the understanding that the enterprise was to be "based in the new world rather than in London".[5] Small towns in Massachusetts were compared to city-states in a somewhat oligarchic form, but an oligarchy based on "perceived virtue" rather than wealth or birth.[5] The notion of self-government became accepted in the colonies although it wasn't totally free from challenges; in the 1670s, the Lords of Trade and Plantations (a royal committee regulating mercantile trade in the colonies) tried to annul the Massachusetts Bay charter, but by 1691, the New England colonies had reinstalled their previous governments.[6]

Voting was established as a precedent early on; in fact, one of the first things that Jamestown settlers did was conduct an election.[7] Typically, voters were white males described as "property owners" aged twenty-one and older, but sometimes the restrictions were greater, and in practice, persons able to participate in elections were few.[7] Women were prevented from voting (although there were a few exceptions) and African-Americans were excluded.[7] The colonists never thought of themselves as subservient but rather as having a loose association with authorities in London.[6] Representative government sprung up spontaneously in various colonies, and during the colonial years, it was recognized and ratified by later charters.[8] But the colonial assemblies passed few bills and did not conduct much business, but dealt with a narrow range of issues, and legislative sessions lasted weeks (occasionally longer), and most legislators could not afford to neglect work for extended periods; so wealthier people tended to predominate in local legislatures.[7] Office holders tended to serve from a sense of duty and prestige, and not for financial benefit.[7]

Campaigning by candidates was different from today's. There were no mass media or advertising. Candidates talked with voters in person, walking a line between undue familiarity and aloofness. Prospective officeholders were expected to be at the polls on election day and made a point to greet all voters. Failure to appear or to be civil to all could be disastrous. In some areas, candidates offered voters food and drink, evenhandedly giving "treats" to opponents as well as supporters.––Ed Crews.[7]

Taxes were generally based on real estate since it was fixed in place, plainly visible, and its value was generally well known, and revenue could be allocated to the government unit where the property was located.[9]

After the American Revolution, the electorate chose the governing councils in almost every American municipality, and state governments began issuing municipal charters.[10] During the 19th century, many municipalities were granted charters by the state governments and became technically municipal corporations.[10] Townships and county governments and city councils shared much of the responsibility for decision-making which varied from state to state.[10] As the United States grew in size and complexity, decision-making authority for issues such as business regulation, taxation, environmental regulation moved to state governments and the national government, while local governments retained control over such matters as zoning issues, property taxes, and public parks.[citation needed] The concept of "zoning" originated in the U.S. during the 1920s, according to one source, in which state law gave certain townships or other local governing bodies authority to decide how land was used; a typical zoning ordinance has a map of a parcel of land attached with a statement specifying how that land can be used, how buildings can be laid out, and so forth.[11] Zoning legitimacy was upheld by the Supreme Court in its Euclid v. Ambler decision.[11]

Types

The Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution makes local government a matter of state rather than federal law, with special cases for territories and the District of Columbia. As a result, the states have adopted a wide variety of systems of local government. The United States Census Bureau conducts the Census of Governments every five years to compile statistics on government organization, public employment, and government finances. The categories of local government established in this Census of Governments is a convenient basis for understanding local government in the United States. The categories are as follows:[1]

- County Governments

- Town or Township Governments

- Municipal Governments

- Special-Purpose Local Governments

County governments

County governments are organized local governments authorized in state constitutions and statutes. Counties and county-equivalents form the first-tier administrative division of the states.

All the states are divided into counties or county-equivalents for administrative purposes, although not all counties or county-equivalents have an organized county government. County government has been eliminated through Connecticut and Rhode Island, as well as in parts of Massachusetts. The Unorganized Borough in Alaska also does not operate under a county level government. Additionally, a number of independent cities and consolidated city-counties operate under municipal governments that serve the functions of both city and county.

In areas lacking a county government, services are provided either by lower level townships or municipalities, or the state.

Town or township governments

Town or township governments are organized local governments authorized in the state constitutions and statutes of 20 Northeastern and Midwestern states,[1] established to provide general government for a defined area, generally based on the geographic subdivision of a county. Depending on state law and local circumstance, a township may or may not be incorporated, and the degree of authority over local government services may vary greatly.

Towns in the six New England states and townships in New Jersey and Pennsylvania are included in this category despite the fact that they are legally municipal corporations since their structure has no necessary relation to concentration of population,[1] which is typical of municipalities elsewhere in the United States. In particular, towns in New England have considerably more power than most townships elsewhere and often function as independent cities in all but name, typically exercising the full range of powers that are divided between counties, townships, and cities in other states.[12]

An additional dimension that distinguishes township governments from municipalities is the historical circumstance surrounding their formation. For example, towns in New England are also defined by a tradition of local government presided over by town meetings — assemblies open to all voters to express their opinions on public policy.

The term "town" is also used for a local level of government in New York and Wisconsin. The terms "town" and "township" are used interchangeably in Minnesota.

Municipal governments

Municipal governments are organized local governments authorized in state constitutions and statutes, established to provide general government for a defined area, generally corresponding to a population center rather than one of a set of areas into which a county is divided. The category includes those governments designated as cities, boroughs (except in Alaska), towns (except in Minnesota and Wisconsin), and villages.[13] This concept corresponds roughly to the "incorporated places" that are recognized in Census Bureau reporting of population and housing statistics, although the Census Bureau excludes New England towns from their statistics for this category, and the count of municipal governments excludes places that are governmentally inactive.

Municipalities range in size from the very small (e.g., the Village of Lazy Lake, Florida, with 24 residents), to the very large (e.g., New York City, with about 8 million people), and this is reflected in the range of types of municipal governments that exist in different areas.

In most states, county and municipal governments exist side-by-side. There are exceptions to this, however. In some states, a city can, either by separating from its county or counties or by merging with one or more counties, become independent of any separately functioning county government and function both as a county and as a city. Depending on the state, such a city is known as either an independent city or a consolidated city-county. Such a jurisdiction constitutes a county-equivalent and is analogous to a unitary authority in other countries. In Connecticut, Rhode Island, and parts of Massachusetts, counties exist only to designate boundaries for such state-level functions as park districts or judicial offices (Massachusetts). Municipal governments are usually administratively divided into several departments, depending on the size of the city.

Special-purpose local governments

School districts

School districts are organized local entities providing public elementary and secondary education which, under state law, have sufficient administrative and fiscal autonomy to qualify as separate governments. The category excludes dependent public school systems of county, municipal, township, or state governments (e.g., school divisions).

Special districts

Special districts are all organized local entities other than the four categories listed above, authorized by state law to provide designated functions as established in the district's charter or other founding document, and with sufficient administrative and fiscal autonomy to qualify as separate governments;[14] known by a variety of titles, including districts, authorities, boards, commissions, etc., as specified in the enabling state legislation. A special district may serve areas of multiple states if established by an interstate compact. Special districts are widely popular, their numbers having grown almost 300% from 1957 to 2007.[15]

Councils or associations of governments

It is common for residents of major U.S. metropolitan areas to live under six or more layers of special districts as well as a town or city, and a county or township.[16] In turn, a typical metro area often consists of several counties, several dozen towns or cities, and a hundred (or more) special districts. In one state, California, the fragmentation problem became so bad that in 1963 the California Legislature created Local Agency Formation Commissions in 57 of the state's 58 counties; that is, government agencies to supervise the orderly formation and development of other government agencies. One effect of all this complexity is that victims of government negligence occasionally sue the wrong entity and do not realize their error until the statute of limitations has run against them.[17]

Because efforts at direct consolidation have proven futile, U.S. local government entities often form "councils of governments," "metropolitan regional councils," or "associations of governments." These organizations serve as regional planning agencies and as forums for debating issues of regional importance, but are generally powerless relative to their individual members.[18] Since the late 1990s, "a movement, frequently called 'New Regionalism,' accepts the futility of seeking consolidated regional governments and aims instead for regional structures that do not supplant local governments."[19]

Dillon's Rule

Unlike the relationship of federalism that exists between the U.S. government and the states (in which power is shared), municipal governments have no power except what is granted to them by their states. This legal doctrine was established by Judge John Forrest Dillon in 1872 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Hunter v. Pittsburgh, 207 U.S. 161 (1907), which upheld the power of Pennsylvania to consolidate the city of Allegheny into the city of Pittsburgh, despite the wishes of the majority of Allegheny residents. In effect, state governments can place whatever restrictions they choose on their municipalities (including merging municipalities, controlling them directly, or abolishing them outright), as long as such rules don't violate the state's constitution.

Dillon's Rule does not apply in all states of the United States. The constitutional provisions of some states provide specific rights for municipalities and counties.[20] State constitutions which allow counties or municipalities to enact ordinances without the legislature's permission are said to provide home rule authority.[21] A state which is both a home rule state and a Dillon's Rule state applies Dillon's Rule to matters or governmental units not accounted for in the constitutional amendment or statutes which grant home rule. New Jersey, for example, provides for home rule.[22]

Governing bodies

The nature of both county and municipal government varies not only between states, but also between different counties and municipalities within them. Local voters are generally free to choose the basic framework of government from a selection established by state law.[1]

In most cases both counties and municipalities have a governing council, governing in conjunction with a mayor or president. Alternatively, the institution may be of the council-manager government form, run by a city manager under direction of the city council. In the past the municipal commission was also common.

The ICMA has classified local governments into five common forms: mayor–council, council–manager, commission, town meeting, and representative town meeting.[23]

In addition to elections for a council or mayor, elections are often also held for positions such as local judges, the sheriff (head of the county's police department), and other offices.

Indian reservations

While their territory nominally falls within the boundaries of individual states, Indian reservations actually function outside of their control. The reservation is usually controlled by an elected tribal council which provides local services.

Census of local government

A census of all local governments in the country is performed every 5 years by the United States Census Bureau, in accordance with 13 USC 161.

| Governments in the United States[1] (not including insular areas) | |

|---|---|

| Type | Number |

| Federal | 1 |

| State | 50 |

| County | 3,034 |

| Municipal (city, town, village...) * | 19,429 |

| Township (in some states called Town) ** | 16,504 |

| School district | 13,506 |

| Special purpose (utility, fire, police, library, etc.) |

35,052 |

| Total | 87,576 |

)* note: Municipalities are any incorporated places, such as cities, towns, villages, boroughs, etc.

)** note: New England towns and towns in New York and Wisconsin are classified as civil townships for census purposes.

Examples in individual states

The following sections provide details of the operation of local government in a selection of states, by way of example of the variety that exists across the country.

Alaska

Alaska calls its county equivalents "boroughs," functioning similar to counties in the Lower 48; however, unlike any other state, not all of Alaska is subdivided into county-equivalent boroughs. Owing to the state's low population density, most of the land is contained in what the state terms the Unorganized Borough which, as the name implies, has no intermediate borough government of its own, but is administered directly by the state government. Many of Alaska's boroughs are consolidated city-borough governments; other cities exist both within organized boroughs and the Unorganized Borough.

California

California has several different and overlapping forms of local government. Cities, counties, and the one consolidated city-county can make ordinances (local laws), including the establishment and enforcement of civil and criminal penalties.

The entire state is subdivided into 58 counties (e.g., Los Angeles County). The only type of municipal entity is the city (e.g., Los Angeles), although cities may either operate under "general law" or a custom-drafted charter. California has never had villages, never really used townships (they were for surveying and judicial purposes only), and allows cities to call themselves "towns" if they wish, but the name "town" is purely cosmetic with no legal effect. As a result, California has several towns with large populations in the tens of thousands and several cities that are home to only a few hundred people.

California cities are granted broad plenary powers under the California Constitution to assert jurisdiction over just about anything, and they cannot be abolished or merged without the consent of a majority of their inhabitants. For example, Los Angeles runs its own water and power utilities and its own elevator inspection department, while practically all other cities rely upon private utilities and the state elevator inspectors. San Francisco is unique in that it is the only consolidated city-county in the state.

The city of Lakewood pioneered the Lakewood Plan, a contract under which a city reimburses a county for performing services which are more efficiently performed on a countywide basis. Such contracts have become very popular throughout California and many other states, as they enable city governments to concentrate on particular local concerns like zoning. A city which contracts out most of its services, particularly law enforcement, is known as a contract city.

There are also thousands of "special districts", which are areas with a defined territory in which a specific service is provided, such as schools or fire stations. These entities lack plenary power to enact laws, but do have the power to promulgate administrative regulations that often carry the force of law within land directly controlled by such districts. Many special districts, particularly those created to provide public transportation or education, have their own police departments (e.g. Bay Area Rapid Transit District/BART Police and Los Angeles Unified School District/Los Angeles School Police Department).

District of Columbia

The District of Columbia is unique within the United States in that it is under the direct authority of the U.S. Congress, rather than forming part of any state. Actual government has been delegated under the District of Columbia Home Rule Act to a city council which effectively also has the powers given to county or state governments in other areas. Under the act, the Council of the District of Columbia has the power to write laws, as a state's legislature would, moving the bill to the mayor to sign into law. Following this, the United States Congress has the power to overturn the law.

Georgia

The state of Georgia is divided into 159 counties (the largest number of any state other than Texas), each of which has had home rule since at least 1980. This means that Georgia's counties not only act as units of state government, but also in much the same way as municipalities.

All municipalities are classed as a "city", regardless of population size. For an area to be incorporated as a city special legislation has to be passed by the General Assembly (state legislature); typically the legislation requires a referendum amongst local voters to approve incorporation, to be passed by a simple majority. This most recently happened in 2005 and 2006 in several communities near Atlanta. Sandy Springs, a city of 85,000 bordering Atlanta to the north, incorporated in December 2005. One year later, Johns Creek (62,000) and Milton (20,000) incorporated, which meant that the entirety of north Fulton County was now municipalized. The General Assembly also approved a plan that would potentially establish two new cities in the remaining unincorporated portions of Fulton County south of Atlanta: South Fulton and Chattahoochee Hills. Chattahoochee Hills voted to incorporate in December 2007; South Fulton voted against incorporation, and is the only remaining unincorporated portion of Fulton County.

City charters may be revoked either by the legislature or by a simple majority referendum of the city's residents; the latter last happened in 2004, in Lithia Springs. Revocation by the legislature last occurred in 1995, when dozens of cities were eliminated en masse for not having active governments, or even for not offering at least three municipal services required of all cities.

New cities may not incorporate land less than 3 miles (4.8 km) from an existing city without approval from the General Assembly. The body approved all of the recent and upcoming creations of new cities in Fulton County.

Four areas have a "consolidated city-county" government: Columbus, since 1971; Athens, since 1991; Augusta, since 1996; and Macon, which was approved by voters in 2012.

Hawaii

Hawaii is the only U.S. state that has no incorporated municipalities. Instead it has four counties and the "consolidated city-county" of Honolulu. All communities are considered to be census-designated places, with the exact boundaries being decided upon by co-operative agreement between the Governor's office and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Kalawao County is the second smallest county in the United States, and is often considered part of Maui County.

Louisiana

In Louisiana, counties are called parishes; likewise, the county seat is known as the parish seat. The difference in nomenclature does not reflect a fundamental difference in the nature of government, but is rather a reflection of the state's unique status as a former Spanish colony (although a small number of other states once had parishes too).

Maryland

Maryland has 23 counties. The State Constitution charters the City of Baltimore as an independent city, which is the functional equivalent of a county, and is separate from any county — e.g., there is also a Baltimore County, but its county seat is in Towson, not in the City of Baltimore. Other than Baltimore, all cities are the same, and there is no difference between a municipality called a city or a town. Cities and towns are chartered by the legislature.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has 67 counties. With the exception of Philadelphia and Allegheny, counties are governed by three to seven county commissioners who are elected every four years; the district attorney, county treasurer, sheriff, and certain classes of judge ("judges of election") are also elected separately. Philadelphia has been a consolidated city-county since 1854 and has had a consolidated city-county government since 1952. Allegheny County has had a council/chief executive government since 2001, while still retaining its townships, boroughs and cities.

Each county is divided into municipal corporations, which can be one of four types: cities, boroughs, townships, and incorporated towns. The Commonwealth does not contain any unincorporated land that is not served by a local government. However, the US Postal Service has given names to places within townships that are not incorporated separately. For instance King of Prussia is a census-designated place but has no local government of its own. It is rather contained within Upper Merion Township, governed by Upper Merion's supervisors, and considered to be a part of the township.

Townships are divided into two classes, depending on their population size and density. Townships of the "First Class" have a board made up of five to fifteen commissioners who are elected either at-large or for a particular ward to four-year terms, while those of the "Second Class" have a board of three to five supervisors who are elected at-large to six-year terms. Some townships have adopted a home rule charter which allows them to choose their form of government. One example is Upper Darby Township, in Delaware County, which has chosen to have a "mayor-council" system similar to that of a borough.

Boroughs in Pennsylvania are governed by a "mayor-council" system in which the mayor has only a few powers (usually that of overseeing the municipal police department, if the borough has one), while the borough council has very broad appointment and oversight. The council president, who is elected by the majority party every two years, is equivalent to the leader of a council in the United Kingdom; his or her powers operate within boundaries set by the state constitution and the borough's charter. A small minority of the boroughs have dropped the mayor-council system in favor of the council-manager system, in which the council appoints a borough manager to oversee the day-to-day operations of the borough. As in the case of townships, a number of boroughs have adopted home rule charters; one example is State College, which retains the mayor-council system that it had as a borough.

Bloomsburg is the Commonwealth's only incorporated town; McCandless Township in Allegheny County calls itself a town, but it officially remains a township with a home rule charter.

Cities in Pennsylvania are divided into four classes: Class 1, Class 2, Class 2A, and Class 3. Class 3 cities, which are the smallest, have either a mayor-council system or a council-manager system like that of a borough, although the mayor or city manager has more oversight and duties compared to their borough counterparts. Pittsburgh and Scranton are the state's only Class 2 and Class 2A cities respectively, and have mayors with some veto power, but are otherwise still governed mostly by their city councils.

Philadelphia is the Commonwealth's only Class 1 city. It has a government similar to that of the Commonwealth itself, with a mayor with strong appointment and veto powers and a 17-member city council that has both law-making and confirmation powers. Certain types of legislation that can be passed by the city government require state legislation before coming into force. Unlike the other cities in Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia city government also has oversight of county government, and as such controls the budget for the district attorney, sheriff, and other county offices that have been retained from the county's one-time separate existence; these offices are elected for separately than those for the city government proper.

Texas

Texas has 254 counties, the most of any state.

Each county is governed by a five-member Commissioners Court, which consists of a County Judge (elected at-large) and four Commissioners (elected from single-member precincts). The County Judge has no veto authority over the decisions of the Court, s/he has one vote along with the other Commissioners. In smaller counties, the County Judge also performs judicial functions, while in larger counties his/her role is limited to the Court. Elections are held on a partisan basis.

Counties have no home rule authority; their authority is strictly limited by the State. They operate in areas which are considered "unincorporated" (those parts not within the territory of a city; Texas does not have townships) unless the city has contracted with the county for essential services. In plain English, Texas counties merely exist to deliver specific types of services at the local level as prescribed by state law, but cannot enact or enforce local ordinances.

As one textbook produced for use in Texas schools has openly acknowledged, Texas counties are prone to inefficient operations and are vulnerable to corruption, for several reasons.[24] First, most of them do not have a merit system but operate on a spoils system, so that many county employees obtain their positions through loyalty to a particular political party and commissioner rather than whether they actually have the skills and experience appropriate to their positions.[24] Second, most counties have not centralized purchasing into a single procurement department which would be able to seek quantity discounts and carefully scrutinize bids and contract awards for unusual patterns.[24] Third, in 90 percent of Texas counties, each commissioner is individually responsible for planning and executing their own road construction and maintenance program for their own precinct, which results in poor coordination and duplicate construction machinery.[24]

Cities may be either general law or home rule. Once a city reaches 5,000 in population, it may submit a ballot petition to create a "city charter" and operate under home rule status (they will maintain that status even if the population falls under 5,000) and may choose its own form of government (weak or strong mayor-council, commission, council-manager). Cities under general law status have only those powers authorized by the State. Annexation policies are highly dependent on whether the city is general law (annexation can only occur with the consent of the landowners) or home rule (no consent is required, but if the city fails to provide essential services, the landowners can petition for de-annexation), and city boundaries can cross county ones. The city council can be elected either at-large or from single-member districts. Ballots are on a nonpartisan basis (though, generally, the political affiliation of the candidates is commonly known).

With the exception of the Stafford Municipal School District, all 1,000+ school districts in Texas are "independent" school districts. State law requires seven trustees, which can be elected either at-large or from single-member districts. Ballots are non-partisan. The Texas Education Agency has state authority to order consolidation of school districts, generally for repeated failing performance as was the case with the Wilmer-Hutchins Independent School District.

In addition, state law allows the creation of special districts, such as hospital districts or water supply districts.

Texas does not provide for independent cities nor for consolidated city-county governments. However, local governments are free to enter into "interlocal agreements" with other ones, primarily for efficiency purposes (a common example is for cities and school districts in a county to contract with the county for property tax collection; thus, each resident receives only one property bill).

Virginia

Virginia is divided into 95 counties and 38 cities. All cities are independent cities, which mean that they are separate from, and independent of, any county they may be near or within. Cities in Virginia thus are the equivalent of counties as they have no higher local government intervening between them and the state government. The equivalent in Virginia to what would normally be an incorporated city in any other state, e.g. a municipality subordinate to a county, is a town. For example, there is a County of Fairfax as well as a totally independent City of Fairfax, which technically is not part of Fairfax County even though the City of Fairfax is the county seat of Fairfax County. Within Fairfax County, however, is the incorporated town of Vienna, which is part of Fairfax County. Similar names do not necessarily reflect relationships; Franklin County is far from the city of Franklin, while Charles City is an unincorporated community in Charles City County, and there is no city of Charles.

Other states

- Administrative divisions of Connecticut

- Administrative divisions of Massachusetts

- Local government in New Hampshire

- Local government in New Jersey

- Local government in New Mexico

- Administrative divisions of New York

- Administrative divisions of Wisconsin

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g U.S. Census Bureau. 2012 Census of Governments

- ^ a b "Emergence of Colonial Government". United States History. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

In all phases of colonial development, a striking feature was the lack of controlling influence by the English government. All colonies except Georgia emerged as companies of shareholders, or as feudal proprietorships stemming from charters granted by the Crown. The fact that the king had transferred his immediate sovereignty over the New World settlements to stock companies and proprietors did not, of course, mean that the colonists in America were necessarily free of outside control. Under the terms of the Virginia Company charter, for example, full governmental authority was vested in the company itself. Nevertheless, the crown expected that the company would be resident in England. Inhabitants of Virginia, then, would have no more voice in their government than if the king himself had retained absolute rule.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Henry William Elson (1904). "Colonial Government". MacMillan Company. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

In methods of local government the colonies were less uniform than in the general government. As stated in our account of Massachusetts, the old parish of England became the town in New England. ...

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Henry William Elson (1904). "Colonial Government". MacMillan Company. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

In no colony was universal suffrage to be found.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "HISTORY OF BRITISH COLONIAL AMERICA". History World. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

In 1629 a Puritan group secures from the king a charter to trade with America, as the Massachusetts Bay Company. Led by John Winthrop, a fleet of eleven vessels sets sail for Massachusetts in 1630. The ships carry 700 settlers, 240 cows and 60 horses. Winthrop also has on board the royal charter of the company. The enterprise is to be based in the new world rather than in London. This device is used to justify a claim later passionately maintained by the new colony - that it is an independent political entity, entirely responsible for its own affairs.In 1630 Winthrop selects Boston as the site of the first settlement, and two years later the town is formally declared to be the capital of the colony.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Emergence of Colonial Government". United States History. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

For their part, the colonies had never thought of themselves as subservient. Rather, they considered themselves chiefly as commonwealths or states, much like England itself, having only a loose association with the authorities in London. In one way or another, exclusive rule from the outside withered away.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Ed Crews (Spring 2007). "Voting in Early America". history.org. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

Among the first things the Jamestown voyagers did when they set up English America's first permanent settlement was conduct an election. Nearly as soon as they landed—April 26, 1607, by their calendar—the commanders of the 105 colonists unsealed a box containing a secret list of seven men picked in England to be the colony's council and from among whom the councilors were to pick a president.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Henry William Elson (1904). "Colonial Government". MacMillan Company. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

The system of representative government was allowed, but not required, by the early charters. But after it had sprung up spontaneously in various colonies, it was recognized and ratified by the later charters, as in those of Connecticut and Rhode Island, and the second charter of Massachusetts, though it was not mentioned in the New York grant. The franchise came to be restricted by some property qualifications in all the colonies, in most by their own act, as by Virginia in 1670, or by charter, as in Massachusetts, 1691.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Glenn W. Fisher (2010-02-01). "History of Property Taxes in the United States". EH.net (Economic History Association). Retrieved 2010-06-16.

The property tax, especially the real estate tax, was ideally suited to such a situation. Real estate had a fixed location, it was visible, and its value was generally well known. Revenue could easily be allocated to the governmental unit in which the property was located.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c "Political Dictionary: local government". answers.com. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

Both county governments and towns were significant, sharing responsibility for local rule. In the middle colonies and in Maryland and Virginia as well, the colonial governors granted municipal charters to the most prominent communities, endowing them with the powers and privileges of a municipal corporation. Although in some of these municipalities the governing council was elected ... By the 1790s the electorate chose the governing council in every American municipality. Moreover, the state legislatures succeeded to the sovereign prerogative of the royal governors and thenceforth granted municipal charters. During the nineteenth century, thousands of communities became municipal corporations. Irritated by the many petitions for incorporation burdening each legislative session, nineteenth-century state legislatures enacted general municipal incorporation laws that permitted communities to incorporate simply by petitioning the county authorities.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Getting a Grip on Zoning Regulations". useful-community-development.org. 2010-06-16. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

Zoning is a concept that originated in the United States in the 1920s. State law often gives certain townships, municipal governments, county governments, or groups of governments acting together the power to zone.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Osborne M. Reynolds, Jr., Local Government Law, 3rd ed. (St. Paul: West, 2009), 30.

- ^ Reynolds, 24.

- ^ Reynolds, 31.

- ^ Reynolds, 31-32.

- ^ Reynolds, 33.

- ^ Spencer v. Merced County Office of Education, 59 Cal. App. 4th 1429 (1997).

- ^ Reynolds, 53.

- ^ Reynolds, 55.

- ^ Adrian, Charles R. and Fine, Michael R. (1991) State and Local Politics Lyceum Books/Nelson Hall Publishers, Chicago, page 83, ISBN 0-8304-1285-9

- ^ Allen, J. Michael, III and Hinds, Jamison W. (2001) "Alabama Constitutional Reform" Alabama Law Review 53: pp. 1-30, pages 7-8

- ^ The provisions of this Constitution and of any law concerning municipal corporations formed for local government, or concerning counties, shall be liberally construed in their favor. The powers of counties and such municipal corporations shall include not only those granted in express terms but also those of necessary or fair implication, or incident to the powers expressly conferred, or essential thereto, and not inconsistent with or prohibited by this Constitution or by law. Constitution of the State of New Jersey, Article IV, Section VII (11).

- ^ ICMA

- ^ a b c d Charldean Newell, David Forrest Prindle, and James W. Riddlesperger, Jr., Texas Politics, 11th ed. (Boston: Cengage Learning, 2011), 376-381.

Further reading

- Jon C. Teaford (2009). "Local Government". In Michael Kazin (ed.). Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton University Press. pp. 488?-491. ISBN 1-4008-3356-6.

- Check list of books and pamphlets on municipal government. Chicago Public Library. 1911.

External links

- National Association of Counties

- National League of Cities

- National Association of Towns and Townships

- International City/County Management Association (ICMA)

- U.S. Census Bureau page for local government

- American Public Works Association

- National Association of County Engineers

- National Association of Development Organizations

- National Center for Small Communities

- Municipal Research & Services Center of Washington (MRSC)

- U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. State Laws Governing Local Government Structure and Administration