Maktar

Maktar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Siliana Governorate |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 12,942[1] |

| Time zone | UTC1 (CET) |

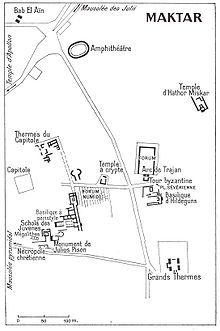

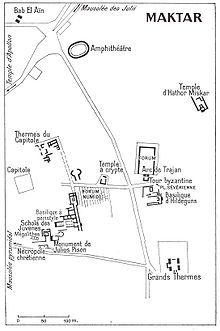

Maktar (Arabic: مكتر, Latin: Mactaris), or Makthar, is a town and Roman-Berber site in Siliana Governorate, Tunisia.[2] It is located at 35°51′38″N 9°12′21″E / 35.86056°N 9.20583°E, around 140 km (90 mi) southwest of Tunis and 60 km (40 mi) southeast of El Kef. The population in 2004 was 12,942.[1]

History

The ancient town was founded by the Numidians as a defense post against the Carthaginians. It was settled by Punics after the destruction of Carthage by the Romans in 146 BC. Numerous inscriptions are recorded through the ruins.[3] Under Roman and Byzantine control, it served as a defense against the local Berber tribes. In 46 BC, it obtained status as a free city and by 146 AD was established as a Roman colony, during which the town saw its greatest development.

It was eventually destroyed by the Banu Hillal tribe in the 10th century.

The modern town lies on a plateau at 900 m (3,000 ft) above sea level. It sits on the other side of a ravine from the Roman remains and is known for its scenic views. The town has a continental climate, with cold winters and warm summers and occasional snowfall during the months of January and February.

History

In the 3rd century BC The Numidians built in the strategic location a fortress which should control the trade routes between Sbeitla, Kairouan and El Kef. The establishment grew rapidly zoom to a larger settlement, which developed under Massinissa a center of Numidia. After the fall of Carthage flocked numerous Punic refugees to Maktar who brought their culture and their skills. Buildings, management system and language were strong Carthaginian influences. Testify many Punic inscriptions and figures but also the remains of temples.

Roman occupation saw, retained the Punic government and administration in the division into suffetes while the immigrant Romans merged in Pagus. The growth of the city continued. As transit point for grain, oil, livestock and textiles and as a transport hub between Carthage, Sufetula, Thugga and Tebessa Mactaris grew into one of the richest cities in the province.

Only under Trajan (97-117), the romanization of the city had prevailed. You got a uniform Roman constitution and the status of Colonia awarded, whereby all residents were automatically given Roman citizenship. The troubles of the third century, which ushered in the decline of the Roman Empire, also influenced Maktar. The decline was halted again under Diocletian (284-305). Maktar survived the invasion of the Vandals and became an important Byzantine fortress. In late antiquity was Mactaris diocese, on the titular Mactaris returns. The Christianization documented in the construction of numerous churches. The devastating raid of the Beni Hilal (1050) led to the complete destruction of the city.

1914 began archaeological excavations of the French, among others with German prisoners of war, and were continued from 1944 on a large scale. Although until now everything has not yet been exposed, include the ruins site, especially for its spas and the Schola of the Juvenes to the most remarkable ancient sites in Tunisia.

Archaeology

Trajan Forum

The rectangular, paved gathering place was designed in the 2nd century for the Roman population, while the indigenous population 50m southwest had its own forum. The place was surrounded by a portico. On its south side by the powerful and well-preserved Arch of Trajan.

The Trajan forum was built by citizens of the city (116AD) on the award of Roman citizenship to parts of the local elite of Mactaris under Trajan.[4]

Large baths

The Great Baths are among the best preserved of its kind in North Africa. The walls of the frigidarium rise up to 15 m up. The building was constructed around the year 200AD and is decorated with oriental acting foliage on the capitals and with a beautiful mosaic floor.

School Juvenum

Begun and completed around the year 200 building complex was the meeting point of the "youth organization", a kind of militia of the young men who perceived some police duties, especially tax collection. In Maktar it consisted of about 70 members. The organization played here as in other Roman provincial cities temporarily an important role. To enter into the upscale military service membership in the strictly managed organization was a prerequisite. The curriculum of the Schola stood beside paramilitary exercises and sports also subjects such as Silo, finance, politics and culture. Over time, the Brotherhood received more and more influence, because the rich citizens of provincial cities defended with their help against the power claims of the central government. So it was even in the year 238 the Emperor Gordian I. himself joined the organization. Emperor Diocletian the Schola was restored the school. The original building, called the Basilica, was used in the Christian era as a church, a Punic sarcophagus from the adjacent necropolis served as altar.

-

the Arch of Trajan

-

Forum and arc of Trajan.

-

Makthar amphithéâtre.jpg

Pre Roman Structures

The site has a beautiful set of megaliths that was searched. Consisting of large slabs, all had a space for the worship of the dead during the laying ceremonies ashes . Megaliths served as a place of collective burial . Excavations of an intact burial chamber, made by Mansour Ghaki, have uncovered a large number of ceramics of various origins, local but also imported. This material has a dating from the early third century BC. BC at the end of the first century . The 17 January 2012 The Tunisian government proposes for future ranking on the World Heritage List of Unesco , as part of the royal mausoleums of Numidia, Mauretania and pre-Islamic monuments .

There are also on site an example of mausoleum pyramid type punicisant, approaching the mausoleum Atban to Dougga . In addition, archaeologists have unearthed a numidian period public square that is thought to be the religious center of the city, due to the presence of temples, which housed a temple of Augustus and Rome.

The temple of Hathor Miskar is well known because of the extensive excavations that were carried out there, even if the remains are poorly preserved. At the center of the sanctuary, archaeologists have found an altar dated to about 100 BC.

Bishopric

The Roman town at Maktar was known as Colonia Aelia Aurelia Mactaris[5] or Mactaris.[6]

It was the seat of a Bishopric in pre Islamic times, which remains a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church to this day. It is in the province of Bizacena, and mentioned by the Notia Africae and ruins of the cities Basilica remain today which have revealed many Christian inscriptions and evidence of two reliquies.

It is in the provence of Bizacena,[7] and mentioned by the Notia Africae Although the diocese effectivly ceased operating with the arrival of the Islamic armies, the see remains a titular of the Roman Catholic church and there have been titular bishops since 1514.[8] The current Bishop is Pedro Dulay Arigo,[9]

There are known to be 6 bishops from Antquity[10] and 20 titular bishops of Maktar, including:

- Marcus of Mactaris[11] fl 325.

- Comparitor fl411 (Donatist)

- Adelfius fl484 (Catholic)

- Germanus[12]

- Rutilius

- Victor 6th century[13]

References

- ^ a b Population Census 2004 National Institute of Statistics Template:Fr icon

- ^ Claude Lepelley: Les cités de l’Afrique romaine. 1981, Bd. 2, pp. 289–295.

- ^ Robert M. Kerr, Latino-Punic Epigraphy: A Descriptive Study of the Inscriptions (Mohr Siebeck, 2010).

- ^ http://db.edcs.eu/epigr/epi_einzel.php?s_sprache=de&p_belegstelle=CIL+08%2C+11798&r_sortierung=Belegstelle

- ^ Inscription de l'Henchir Makter (Colonia Aelia Aurelia Mactaris) 27 juin 1884 Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres / Année 1884 / Volume 28 / Numéro 2 pp. 281-286.

- ^ Henri Marrou Irenaeus, André Mandouze, Anne-Marie Bonnardière , Prosopography of Christian Africa (303-533) p 1314.

- ^ Joseph Bingham, Origines Ecclesiasticae, Volume 3 (Straker, 1843) p231

- ^ Titular Episcopal See of Mactaris at GCatholic.org.

- ^ Mactaris, at CatholicHeirachy.org

- ^ TOULOTTE, Géographie de l'Afrique chrétienne, Byzacène et Tripolitaine (Montreuil-sur-Mer 1894), 127-133.

- ^ Philip Schaff, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: First Series, Volume IV St. Augustine.(Cosimo, Inc., 1 May 2007)p500.

- ^ known only from inscription in Basilica at Maktar.

- ^ Brent D. Shaw, Bringing in the Sheaves: Economy and Metaphor in the Roman World(University of Toronto Press, 2013) p56.

External links

- Lexicorient

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.