Mil Mi-24

| Mi-24 / Mi-25 / Mi-35 | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Mi-24W of the Polish Land Forces | |

| Role | Attack helicopter with transport capabilities |

| National origin | Soviet Union/Russia |

| Manufacturer | Mil |

| First flight | 19 September 1969 |

| Introduction | 1972 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Air Force ca. 50 other users (see Operators section below) |

| Produced | 1969–present |

| Number built | 2,648 |

| Developed from | Mil Mi-8 |

The Mil Mi-24 (Template:Lang-ru; NATO reporting name: Hind) is a large helicopter gunship, attack helicopter and low-capacity troop transport with room for eight passengers.[1] It is produced by Mil Moscow Helicopter Plant and has been operated since 1972 by the Soviet Air Force and its successors, along with more than 30 other nations.

In NATO circles, the export versions, Mi-25 and Mi-35, are denoted with a letter suffix as "Hind D" and "Hind E". Soviet pilots called the Mi-24 the "flying tank" (летающий танк; letayushchiy tank), a term used historically with the famous World War II Soviet Il-2 Shturmovik armored ground attack aircraft. More common unofficial nicknames were "Galina" (or "Galya"), "Crocodile" (Крокодил; Krokodil), due to the helicopter's camouflage scheme and "Drinking Glass" (Стакан; Stakan), because of the flat glass plates that surround earlier Mi-24 variants' cockpits.[2]

Development

During the early 1960s, it became apparent to Soviet designer Mikhail Leont'yevich Mil that the trend towards ever-increasing battlefield mobility would result in the creation of flying infantry fighting vehicles, which could be used to perform both fire support and infantry transport missions. The first expression of this concept was a mock-up unveiled in 1966 in the experimental shop of the Ministry of Aircraft's factory number 329, where Mil was head designer. The mock-up designated V-24 was based on another project, the V-22 utility helicopter, which itself never flew. The V-24 had a central infantry compartment that could hold eight troops sitting back to back, and a set of small wings positioned to the top rear of the passenger cabin, capable of holding up to six missiles or rockets and a twin-barreled GSh-23L cannon fixed to the landing skid.

Mil proposed the design to the heads of the Soviet armed forces. While he had the support of a number of strategists, he was opposed by several more senior members of the armed forces, who believed that conventional weapons were a better use of resources. Despite the opposition, Mil managed to persuade the defence minister's first deputy, Marshal Andrey A. Grechko, to convene an expert panel to look into the matter. While the panel's opinions were mixed, supporters of the project eventually held sway and a request for design proposals for a battlefield support helicopter was issued. The development and use of gunships and attack helicopters by the US Army during the Vietnam War convinced the Soviets of the advantages of armed helicopter ground support, and fostered support for the development of the Mi-24.[3]

Mil engineers prepared two basic designs: a 7-ton single-engine design and a 10.5-ton twin-engine design, both based on the 1,700 hp Izotov TV3-177A turboshaft. Later, three complete mock-ups were produced, along with five cockpit mock-ups to allow the pilot and weapon station operator positions to be fine-tuned.

The Kamov design bureau suggested an army version of their Ka-25 ASW helicopter as a low-cost option. This was considered but later dropped in favor of the new Mil twin-engine design. A number of changes were made at the insistence of the military, including the replacement of the 23 mm cannon with a rapid-fire heavy machine gun mounted in a chin turret, and the use of the 9K114 Shturm (AT-6 Spiral) anti-tank missile.

A directive was issued on 6 May 1968 to proceed with the development of the twin-engine design. Work proceeded under Mil until his death in 1970. Detailed design work began in August 1968 under the codename Yellow 24. A full-scale mock-up of the design was reviewed and approved in February 1969. Flight tests with a prototype began on 15 September 1969 with a tethered hover, and four days later the first free flight was conducted. A second prototype was built, followed by a test batch of ten helicopters.

Acceptance testing for the design began in June 1970, continuing for 18 months. Changes made in the design addressed structural strength, fatigue problems and reduced vibration levels. Also, a 12-degree anhedral was introduced to the wings to address the aircraft's tendency to Dutch roll at speeds in excess of 200 km/h (124 mph), and the Falanga missile pylons were moved from the fuselage to the wingtips. The tail rotor was moved from the right to the left side of the tail, and the rotation direction reversed. The tail rotor now rotated up on the side towards the front of the aircraft, into the downwash of the rotor, which increased the efficiency of the tail rotor. A number of other design changes were made until the production version Mi-24A (izdeliye 245) entered production in 1970, obtaining its initial operating capability in 1971 and was officially accepted into the state arsenal in 1972.[4]

In 1972, following completion of the Mi-24, development began on a unique attack helicopter with transport capability. The new design had a reduced transport capability (three troops instead of eight) and was called the Mi-28, and that of the Ka-50 attack helicopter, which is smaller and more maneuverable and does not have the large cabin for carrying troops. In October 2007, the Russian Air Force announced it would replace its Mi-24 fleet with Mi-28Ns and Ka-52s by 2015.[5][6]

Design

Overview

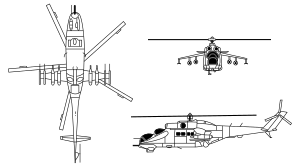

The core of the aircraft was derived from the Mil Mi-8 (NATO reporting name "Hip") with two top-mounted turboshaft engines driving a mid-mounted 17.3 m five-blade main rotor and a three-blade tail rotor. The engine configuration gave the aircraft its distinctive double air intake. Original versions have an angular greenhouse-style cockpit; Model D and later have a characteristic tandem cockpit with a "double bubble" canopy. Other airframe components came from the Mi-14 "Haze". Two mid-mounted stub wings provide weapon hardpoints, each offering three stations, in addition to providing lift. The loadout mix is mission dependent; Mi-24s can be tasked with close air support, anti-tank operations, or aerial combat.

The Mi-24 fuselage is heavily armored and can resist impacts from 12.7 mm (0.50 in) rounds from all angles. The titanium rotor blades are also resistant to 12.7 mm rounds. The cockpit is protected by ballistic-resistant windscreens and a titanium-armored tub.[7] The cockpit and crew compartment are overpressurized to protect the crew in NBC conditions.[8]

Flight characteristics

Considerable attention was given to making the Mi-24 fast. The airframe was streamlined, and fitted with retractable tricycle undercarriage landing gear to reduce drag. At high speed, the wings provide considerable lift (up to a quarter of total lift). The main rotor was tilted 2.5° to the right from the fuselage to compensate for translating tendency at a hover. The landing gear was also tilted to the left so that the rotor would still be level when the aircraft was on the ground, making the rest of the airframe tilt to the left. The tail was also asymmetrical to give a side force at speed, thus unloading the tail rotor.[9]

A modified Mi-24B, named A-10, was used in several speed and time-to-climb world record attempts. The helicopter had been modified to reduce weight as much as possible—one measure was the removal of the stub wings.[4] The official speed record set on 13 August 1975 over a closed 1000 km course of 332.65 km/h (206.7 mph) still stands, as do many of the female-specific records set by the all-female crew of Galina Rastorguyeva and Lyudmila Polyanskaya.[10] On 21 September 1978, the A-10 set the absolute speed record for helicopters with 368.4 km/h (228.9 mph) over a 15/25 km course. The record stood until 1986, when it was broken by the current official record holder, a modified Westland Lynx.[11]

Comparison to Western helicopters

As a combination of armoured gunship and troop transport, the Mi-24 has no direct NATO counterpart. While the UH-1 ("Huey") helicopters were used in the Vietnam War either to ferry troops, or as gunships, they were not able to do both at the same time. Converting a UH-1 into a gunship meant stripping the entire passenger area to accommodate extra fuel and ammunition, and removing its troop transport capability. The Mi-24 was designed to do both, and this was greatly exploited by airborne units of the Soviet Army during the 1980–89 Soviet–Afghan War. The closest Western equivalent was the Sikorsky S-67 Blackhawk, which used many of the same design principles and was also built as a high-speed, high-agility attack helicopter with limited troop transport capability using many components from the existing Sikorsky S-61. The S-67, however, was never adopted for service.[1] Other Western equivalents are the Romanian Army's IAR 330, which is a licence-built armed version of the Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma, and the MH-60 Direct Action Penetrator, a special purpose armed variant of the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk. The Hind has been called the world's only "assault helicopter" due to its combination of firepower and troop-carrying capability.[citation needed]

Operational history

Ogaden War (1977–1978)

The first combat use of the Mi-24 was with the Ethiopian forces during the Ogaden War against Somalia. The helicopters formed part of a massive airlift of military equipment from the Soviet Union, after the Soviets switched sides towards the end of 1977. The helicopters were instrumental in the combined air and ground assault that allowed the Ethiopians to retake the Ogaden, by the beginning of 1978.[12]

Chadian-Libyan conflict (1978–1987)

The Libyan air force used Mi-24A and Mi-25 units during their numerous interventions in Chad's civil war.[9] The Mi-24s were first used in October 1980 in the battle of N'Djamena, where they helped the People's Armed Forces seize the capital.

In March 1987, the Armed Forces of the North, which were backed by the USA and France, captured a Libyan air force base at Ouadi-Doum in Northern Chad. Among the aircraft captured during this raid were three Mi-25s. These were supplied to France, which in turn sent one to the United Kingdom and one to the USA.[4]

Soviet war in Afghanistan (1979–1989)

The aircraft was operated extensively during the Soviet–Afghan War, mainly for bombing Mujahideen fighters. When the U.S. supplied heat-seeking Stinger missiles to the Mujahideen, the Soviet Mi-8 and Mi-24 helicopters proved to be favorite targets of the rebels.

It is difficult to find the total number of Mi-24s used in Afghanistan.[13] At the end of 1990, the whole Soviet Army had 1,420 Mi-24s.[14] During the Afghan war, sources estimated the helicopter strength to be as much as 600 machines, with up to 250 being Mi-24s.[15] Whereas a (formerly secret) 1987 CIA report says that the number of Mi-24s in theatre increased from 85 in 1980 to 120 in 1985.[16]

First deployment and combat

In April 1979, Mi-24s were supplied to the Afghan government to deal with Mujahideen guerrillas.[17] The Afghan pilots were well-trained and made effective use of their machines, but the Mujahideen were not easy targets. The first Mi-24 to be lost in action was shot down by guerrillas on 18 July 1979.[18][19] The situation in Afghanistan grew worse, and on 27 December 1979, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan.

Despite facing strong resistance from Afghan rebels, the Mi-24 proved to be very destructive. The rebels called the Mi-24 "Shaitan-Arba" (Satan's Chariot)".[17] In one case, an Mi-24 pilot who was out of ammunition managed to rescue a company of infantry by maneuvering aggressively towards Mujahideen guerrillas and scaring them off. The Mi-24 was popular with ground troops, since it could stay on the battlefield and provide fire as needed, while "fast mover" strike jets could only stay for a short time before heading back to base to refuel.

The Mi-24's favoured munition was the 80-millimetre (3.1 in) S-8 rocket, the 57 mm (2.2 in) S-5 having proven too light to be effective. The 23 mm (0.91 in) gun pod was also popular. Extra rounds of rocket ammunition were often carried internally so that the crew could land and self-reload in the field. The Mi-24 could carry ten 100-kilogram (220 lb) iron bombs for attacks on camps or strongpoints, while harder targets could be dealt with a load of four 250-kilogram (550 lb) or two 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) iron bombs.[20] Some Mi-24 crews became experts at dropping bombs precisely on targets. Fuel-air explosive bombs were also used in a few instances, though crews initially underestimated the sheer blast force of such weapons and were caught by the shock waves.

Combat experience quickly demonstrated the disadvantages of having an Mi-24 carrying troops. Gunship crews found the soldiers a concern and a distraction while being shot at, and preferred to fly lightly loaded anyway, especially given their operations from high ground altitudes in Afghanistan. Mi-24 troop compartment armour was often removed to reduce weight. Troops would be carried in Mi-8 helicopters while the Mi-24s provided fire support.

It proved useful to carry a technician in the Mi-24's crew compartment to handle a light machine gun in a window port. This gave the Mi-24 some ability to "watch its back" while leaving a target area. In some cases, a light machine gun was fitted on both sides to allow the technician to move from one side to the other without having to take the machine gun with him.

This weapon configuration still left the gunship blind to the direct rear, and Mil experimented with fitting a machine gun in the back of the fuselage, accessible to the gunner through a narrow crawl-way. The experiment was highly unsuccessful, as the space was cramped, full of engine exhaust fumes, and otherwise unbearable. During a demonstration, an overweight Soviet Air Force general got stuck in the crawl-way.[4] Operational Mi-24s were retrofitted with rear-view mirrors to help the pilot spot threats and take evasive action.

Besides protecting helicopter troop assaults and supporting ground actions, the Mi-24 also protected convoys, using rockets with flechette warheads to drive off ambushes; performed strikes on predesignated targets; and engaged in "hunter-killer" sweeps. Hunter-killer Mi-24s operated at a minimum in pairs, but were more often in groups of four or eight, to provide mutual fire support. The Mujahideen learned to move mostly at night to avoid the gunships, and in response the Soviets trained their Mi-24 crews in night-fighting, dropping parachute flares to illuminate potential targets for attack. The Mujahideen quickly caught on and scattered as quickly as possible when Soviet target designation flares were lit nearby.

Attrition in Afghanistan

The war in Afghanistan brought with it losses by attrition.[17] The environment itself, dusty and often hot, was rough on the machines; dusty conditions led to the development of the PZU air intake filters. The rebels' primary air-defense weapons early in the war were heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft cannons, though anything smaller than a 23 millimetre shell generally did not do much damage to an Mi-24. The cockpit glass panels were resistant to 12.7 mm (.50 in caliber) rounds.

The rebels also used Soviet-made shoulder-launched, heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and American Redeye shoulder-launched SAMs, which had either been captured from the Soviets or their Afghan allies or were supplied from Western sources. Many of them came from stocks that the Israelis had captured during their wars with Soviet backed states in the Middle East. Owing to a combination of the limited capabilities of these early types of missiles, poor training and poor material condition of the missiles, they were not particularly effective. The RPG-7, originally developed as an antitank weapon, was the first effective countermeasure to the Hind. However, the RPG-7, not being designed for air defense, had several shortcomings owing to its design. Often, attempting to use one to shoot down a helicopter could lead to the user injuring himself with the rocket's backblast.

From 1986,[20] the CIA began supplying the Afghan rebels with newer Stinger shoulder-launched, heat-seeking SAMs.[21] These were a marked improvement over earlier weapons, and while their actual military impact was not irrelevant, their real value was their demoralization and deterrent value against air power, and their propaganda worth to anti-Soviet groups. The Stinger missile locked on to infra-red emissions from the aircraft, particularly engine exhaust, and was resistant to interference from decoy flares. Countermeasure flares and missile warning systems were later installed in all Soviet Mil Mi-2, Mi-8, and Mi-24 helicopters, giving pilots a chance to evade the missile. Heat dissipaters were also fitted to exhausts to decrease the Mi-24's heat signature. Tactical and doctrinal changes were introduced to make it harder for the enemy to deploy these weapons effectively. These reduced the Stinger threat, but did not eliminate it.

Initially, the attack doctrine of the Mi-24 was to approach its target from high altitude and dive downwards. After the introduction of the Stinger, doctrine changed to "nap of the earth" flying, where they approached very low to the ground and engaged more laterally, popping up to only about 200 ft (61 m) in order to aim rockets or cannons.[22]

Mi-24s were also used to shield jet transports flying in and out of Kabul from Stingers. The gunships carried flares to blind the heat-seeking missiles. The crews called themselves "Mandatory Matrosovs", after a Soviet hero of the Second World War who threw himself across a German machine gun to let his comrades break through.

According to Russian sources, 74 helicopters were lost, including 27 shot down by Stinger and two by Redeye.[20] In many cases, however, the helicopters, thanks to their armour and the durability of construction, withstood significant damage and were able to return to base.

Mi-24 crews and end of Soviet involvement

Mi-24 crews carried AK-74 assault rifles and other hand-held weapons to give them a better chance of survival if forced down.[17] Early in the war, Marat Tischenko, head of the Mil design bureau visited Afghanistan to see what the troops thought of his helicopters, and gunship crews put on several displays for him. They even demonstrated maneuvers, such as barrel rolls, which design engineers considered impossible. An astounded Tischenko commented, "I thought I knew what my helicopters could do, now I'm not so sure!"[17]

The last Soviet Mi-24 shot down was during the night of 2 February 1989, with both crewmen killed. It was also the last Soviet helicopter lost during nearly 10 years of warfare.[20]

Mi-24s in Afghanistan after Soviet withdrawal

Mi-24s passed on to Soviet-backed Afghan forces during the war remained in dwindling service in the grinding civil war that continued after the Soviet withdrawal.[17]

Afghan Air Force Mi-24s in the hands of the ascendant Taliban gradually became inoperable, but a few flown by the Northern Alliance, which had Russian assistance and access to spares, remained operational up to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001. In 2008, the Afghan Air Force took delivery of six refurbished Mi-35 helicopters, purchased from the Czech Republic. The Afghan pilots were trained by India and began live firing exercises in May 2009 in order to escort Mi-17 transport helicopters on operations in restive parts of the country.

Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988)

The Mi-25 saw considerable use by the Iraqi Army during the long war against Iran.[23] Its heavy armament caused severe losses to Iranian ground forces during the war. However, the Mi-25 lacked an effective anti-tank capability, as it was only armed with obsolete 9M17 Skorpion missiles.[24] This led the Iraqis to develop new gunship tactics, with help from East German advisors. The Mi-25s would form "hunter-killer" teams with French-built Aérospatiale Gazelles, with the Mi-25s leading the attack and using their massive firepower to suppress Iranian air defenses, and the Gazelles using their HOT missiles to engage armoured fighting vehicles. These tactics proved effective in halting Iranian offensives, such as Operation Ramadan in July 1982.[24]

This war also saw the only confirmed air-to-air helicopter battles in history with the Iraqi Mi-25s flying against Iranian AH-1J SeaCobras (supplied by the United States before the Iranian Revolution) on several separate occasions. In November 1980, not long after Iraq's initial invasion of Iran, two Iranian SeaCobras engaged two Mi-25s with TOW wire-guided antitank missiles. One Mi-25 went down immediately, the other was badly damaged and crashed before reaching base.[20][25] The Iranians repeated this accomplishment on 24 April 1981, destroying two Mi-25s without incurring losses to themselves.[20] One Mi-25 was also downed by an IRIAF F-14A.[26]

The Iraqis hit back, claiming the destruction of a SeaCobra on 14 September 1983 (with YaKB machine gun), then three SeaCobras on 5 February 1984[25] and three more on 25 February 1984 (two with Falanga missiles, one with S-5 rockets).[20] After a lull in helicopter losses, each side lost a gunship on 13 February 1986.[20] Later, a Mi-25 claimed a SeaCobra shot down with YaKB gun on 16 February, and a SeaCobra claimed a Mi-25 shot down with rockets on 18 February.[20] The last engagement between the two types was on 22 May 1986, when Mi-25s shot down a SeaCobra. The final claim tally was 10 SeaCobras and 6 Mi-25s destroyed. The relatively small numbers and the inevitable disputes over actual kill numbers makes it unclear if one gunship had a real technical superiority over the other. Iraqi Mi-25s also claimed 43 kills against other Iranian helicopters, such as Agusta-Bell UH-1 Hueys.[25]

In general, the Iraqi pilots liked the Mi-25, in particular for its high speed, long range, high versatility and large weapon load, but disliked the relatively ineffectual weapons and lack of agility.[24] The Mi-25 was also used by Iraq in chemical warfare against Iranians and Kurdish civilians in Halabja.[25]

Nicaraguan civil war (1980–1988)

Mi-25s were also used by the Nicaraguan Army during the civil war of the 1980s.[27][28] Nicaragua received 12 Mi-25s (some sources claim 18) in the mid-1980s to deal with "Contra" insurgents.[25] The Mi-25s performed ground attacks on the Contras and were also fast enough to intercept light aircraft being used by the insurgents. The U.S. Reagan Administration regarded introduction of the Mi-25s as a major escalation of tensions in Central America.

Two Mi-25s were shot down by Stingers fired by the Contras. A third Mi-25 was damaged while pursuing Contras near the Honduran border, when it was intercepted by Honduran F-86 Sabres and A-37 Dragonflies. A fourth was flown to Honduras by a defecting Sandinista pilot in December 1988.

Sri Lankan Civil War (1987–2009)

The Indian Peace Keeping Force (1987–90) in Sri Lanka used Mi-24s when an Indian Air Force detachment was deployed there in support of the Indian and Sri Lankan armed forces in their fight against various Tamil militant groups such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). It is believed that Indian losses were considerably reduced by the heavy fire support from their Mi-24s. The Indians lost no Mi-24s in the operation, as the Tigers had no weapons capable of downing the gunship at the time.[25][29]

Since 14 November 1995, the Mi-24 has been used by the Sri Lanka Air Force in the war against the LTTE and has proved highly effective at providing close air support for ground forces. The Sri Lanka Air Force operates a mix of Mi-24/-35P and Mi-24V/-35 versions attached to its No. 9 Attack Helicopter Squadron. They have recently been upgraded with modern Israeli FLIR and electronic warfare systems. Five were upgraded to intercept aircraft by adding radar, fully functional helmet mounted target tracking systems, and AAMs. More than five Mi-24s have been lost to LTTE MANPADs, and another two lost in attacks on air bases, with one heavily damaged but later returned to service.[29]

Gulf War (1991)

The Mi-24 was also heavily employed by the Iraqi Army during their invasion of Kuwait, although most were withdrawn by Saddam Hussein when it became apparent that they would be needed to help retain his grip on power in the aftermath of the war. In the ensuing 1991 uprisings in Iraq, these helicopters were used against dissidents as well as fleeing civilian refugees.[30][31]

Sierra Leone Civil War (1991–2002)

Three Mi-24Vs owned by Sierra Leone and flown by South African military contractors, including Neall Ellis, were used against RUF rebels.[32] In 1995, they helped drive the RUF from the capital, Freetown.[33] Neall Ellis also piloted a Mi-24 during the British-led operation Barras against West Side Boys.[34] Guinea also used its Mi-24s against the RUF on both sides of the border and was alleged to have provided air support to the LURD insurgency in northern Liberia in 2001–03.

Croatian War of Independence (1990s)

Twelve Mi-24s were delivered to Croatia in 1993, and were used effectively in 1995 by the Croatian Army in Operation Storm against the army of Krajina. The Mi-24 was used to strike deep into enemy territory and disrupt Krajina army communications. One Croatian Mi-24 crashed near the city of Drvar, Bosnia and Herzegovina due to strong winds. Both the pilot and the operator survived. The Mi-24s used by Croatia were obtained from Ukraine. One Mi-24 was modified to carry Mark 46 torpedoes. The helicopters were withdrawn from service in 2004.[35]

First and Second Wars in Chechnya (1990s–2000s)

During the First and Second Chechen Wars, beginning in 1994 and 1999 respectively, Mi-24s were employed by the Russian armed forces.

In the first year of the Second Chechen War, 11 Mi-24s were lost by Russian forces, about half of which were lost as a result of enemy action.[36]

Peruvian operations (1989–1995)

The Peruvian Air Force received 12 Mi-25Ds from the USSR in 1983–1985 after ordering them in the aftermath of 1981 Paquisha conflict with Ecuador. These have been permanently based at the Vitor airbase near La Joya ever since, operated by the 4th Air Group (formerly the 2nd) of the 211th Air Squadron. Their first deployment occurred in June 1989 during the war against Communist guerrillas in the Peruvian highlands, mainly against Shining Path. Despite the conflict continuing, it has decreased in scale and is now limited to the jungle areas of Valley of Rivers Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro (VRAE).[37][38][39][40]

Peru employed Mi-25s against Ecuadorian forces during the short Cenepa conflict in early 1995. The only loss occurred on 7 February, when a FAP Mi-25 was downed after being hit in quick succession by at least two, probably three, 9K38 Igla shoulder-fired missiles during a low-altitude mission over the Cenepa valley. The three crewmen were killed.[41]

Sudanese Civil War (1995–2005)

In 1995, the Sudanese Air Force acquired six Mi-24s for use in Southern Sudan and the Nuba mountains to engage the SPLA. At least two aircraft were lost in non-combat situations within the first year of operation. A further twelve were bought in 2001,[42] and used extensively in the oil fields of Southern Sudan. Mi-24s were also deployed to Darfur in 2004–5.

First and Second Congo Wars (1996–2003)

Three Mi-24s were used by Mobutu's army and were later acquired by the new Air Force of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[43] These were supplied to Zaire in 1997 as part of a French-Serbian contract. At least one was flown by Serbian mercenaries. One hit a power line and crashed on 27 March 1997, killing the three crew and four passengers.[44] Zimbabwean Mi-24s were also operated in coordination with the Congolese Army.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission employed Indian Air Force Mi-24/-35 helicopters to provide support during the Second Congo War. The IAF has been operating in the region since 2003.[45]

Conflict in Republic of Macedonia (2001)

The Military of the Republic of Macedonia acquired used Ukrainian Mi-24Vs. They were used frequently against Albanian insurgents during the 2001 conflict in Macedonia. The main areas of action were in Tetovo, Radusha and Aracinovo.[46]

Ivorian Civil War (2002–2004)

During the Ivorian Civil War, five Mil Mi-24s piloted by mercenaries were used in support of government forces. They were later destroyed by the French Army in retaliation for an air attack on a French base that killed nine soldiers.[47]

Afghanistan War (2001–present)

In 2008 and 2009, the Czech Republic donated six Mi-24s under the ANA Equipment Donation Programme. As a result, the Afghan National Army Air Corps (ANAAC) now has the ability to escort its own helicopters with heavily armed attack helicopters. Currently, nine Mi-35 attack helicopters are operated by the ANAAC. Major Caleb Nimmo, a United States Air Force Pilot, was the first American to fly the Mi-35 Hind, or any Russian helicopter, in combat.[48][49] On 13 September 2011, a Mi-35 attack chopper of the Afghan Air Force was used to hold back an attack on ISAF and police buildings.[50]

The Polish Helicopter Detachment contributed Mi-24s to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). The Polish pilots trained in Germany before deploying to Afghanistan and currently train with U.S. service personnel. On 26 January 2011, one Mi-24 caught on fire during takeoff from its base in Ghazni. One American and four Polish soldiers evacuated unharmed.[51]

India is also donating Mi-35s to Afghanistan, which is the first time India has transferred lethal military equipment to the war-torn nation. Four helicopters are to be supplied, with three already transferred in January 2016.[52] The three Mi-35s made a big difference in the offensive against militants, according to General John Campbell, commander of US forces in Afghanistan.[53]

Iraq War (March 2003–2011)

The Polish contingent in Iraq has been using six Mi-24Ds since December 2004. One of them crashed on 18 July 2006 in an air base in Al Diwaniyah.[54] Polish Mi-24Ds used in Iraq will not be returning to Poland due to their age, condition, low combat value of the Mi-24D variant, and high shipping costs; depending on their condition, they will be transferred to the New Iraqi Army or scrapped. New Mi-35Ps will be bought by the Polish Army as "replacements of equipment depleted during combat operations" for the Mi-24Ds used and left in Iraq.[citation needed]

War in Somalia (2006–2009)

The Ethiopian Air Force operated about three Mil Mi-35 and ten Mil Mi-24D helicopter gunships in the Somali theater. One was shot down near the Mogadishu International Airport on 30 March 2007 by Somali insurgents.[55]

2008 Russo-Georgian War

Mil Mi-24s were used by both sides during fighting in South Ossetia,[56] During war Georgian Air Force Mi-24s attacked first targets on early morning hour of 8 August, targeting Ossetian presidential palace, second target was cement factory near Tskhinval where major enemy forces and ammunition were located,[56] Last combat mission of GAF Mi-24s was on August 11 when large Russian convoy consisting from light trucks and BMP IFVs which was heading to Georgian village Avnevi was targeted by Mi-24s, completely destroying convoy.[56] Georgian Air Force lost 2 Mi-24s on Senaki air base, they were destroyed by Russian troops on the ground, both helicopters were inoperational.[57] Russian army heavily used Mi-24s in conflict, Russian uprgaded Mi-24PNs were credited for destroying 2 Georgian T-72SIM1 tanks using guided missiles at night time, thought some sources attribute those kills to Mil Mi-28,[56] Russian army did not lost any Mi-24s through contlict, mainly because those helicopters were deployed to areas where Georgian air defence was not active,[56] thought some were damaged by small arms fire and at least one Mi-24 was lost due to technical reasons.

War in Chad (2008)

On returning to Abeche, one of the Chadian Mi-35s made a forced landing at the airport. It was claimed that it was shot down by rebels.[58][59]

Libyan civil war (2011)

The Libyan Air Force Mi-24s were used by both sides to attack enemy positions during the 2011 Libyan civil war.[60] A number were captured by the rebels, who formed the Free Libyan Air Force together with other captured air assets. During the battle for Benina airport, one Mi-35 (serial number 853), was destroyed on the ground on 23 February 2011. In the same action, serial number 854 was captured by the rebels together with an Mi-14 (serial number 1406).[61][62] Two Mi-35s operating for the pro-Gaddafi Libyan Air Force were destroyed on the ground on 26 March 2011 by French aircraft enforcing the no-fly zone.[63] One Free Libyan Air Force Mi-25D (serial number 854, captured at the beginning of the revolt) violated the no-fly-zone on 9 April 2011 to strike loyalist positions in Ajdabiya. It was shot down by Libyan ground forces during the action. The pilot, Captain Hussein Al-Warfali, died in the crash.[64] The rebels claimed that a number of other Mi-25s were shot down.

2010–2011 Ivorian crisis

Ukrainian army Mi-24P helicopters as part of the United Nations peacekeeping force fired four missiles at a pro-Gbagbo military camp in Ivory Coast's main city of Abidjan.[65]

Syrian Civil War (2011–present)

The Syrian Air Force have used Mi-24s to attack rebels throughout Syria, including many of the nation's major cities.[66] Controversy has surrounded an alleged delivery of Mi-25s to the Syrian military, due to Turkey and other NATO members disallowing such arms shipments through their territory.[67]

Syrian insurgents captured at least one damaged or destroyed Mi-24, along with other helicopters, after the fall of Taftanaz Air Base in January 2013.[68]

On 9 July 2016, Russian Ministry of Defense reported that a Russian Mil Mi-35M helicopter was shot down by ISIS killing two pilots in east of Palmyra, Syria while supporting Syrian government forces.[69] This was the first loss of a Russian attack helicopter recorded in Syrian Civil War.

Kachin conflict (2012–2013)

The Myanmar Air Force used the Mi-24 in the Kachin conflict against the Kachin Independence Army.[70]

Post-U.S Iraqi insurgency

The new Iraqi Air Force is currently receiving 40 Mi-35 ordered from Russia as part of an arms deal that includes Mi-28 and Ka-52 attack helicopters, as well as Pantsir air defense systems. The delivery of the first four was announced by then-Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki in November 2013.[71][72]

Their first deployment began in late December against camps of the al-Qaeda linked Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and several Islamist militants in the al-Anbar province that have taken control of several areas of Fallujah and Ramadi.[73] FLIR footage of the strikes has been released by the military.[74]

On 3 October 2014, ISIL militants reportedly used a FN-6 shoulder-launched missile in Baiji, Iraq to shoot down an Iraqi Army Mi-35M attack helicopter.[75] Video footage released by ISIL militants shows at least another two Iraqi Mi-24/35s brought down by light anti-aircraft artillery.[76]

Crimean crisis (2014)

During the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, Russia deployed 13 MI-24s to support their infantry as they advanced through the region. However these aircraft saw no combat during their deployment.[77]

Donbass war (2014)

During the Siege of Sloviansk, on 2 May 2014, two Ukrainian Mi-24s were shot down by pro-Russian insurgents. The Ukrainian armed forces claim that they were downed by MANPADS while on patrol close to Slavyansk.[78] The Ukrainian government confirmed that both aircraft were shot down, along with an Mi-8 damaged by small arms fire. Initial reports mentioned two dead and others wounded; later, five crew members were confirmed dead and one taken prisoner until being released on 5 May.[79][80][81]

On 5 May 2014, another Ukrainian Mi-24 was forced to make an emergency landing after being hit by machine gun fire while on patrol close to Slavyansk. The Ukrainian forces recovered the two pilots and destroyed the helicopter with a rocket strike by an Su-25 aircraft to prevent its capture by pro-Russian insurgents.[82]

Mi-24s supported Sukhoi Su-25 attack aircraft, with MiG-29 fighters providing top cover, during the battle for Donetsk Airport.[83]

Chadian offensive against Boko Haram (2015)

Chadian Mi-24s were used during the 2015 West African offensive against Boko Haram.[84]

Nagorno-Karabakh (2014–2016)

On 12 November 2014, Azerbaijani forces shot down an Armenian forces Mi-24 from a formation of two which were flying along the disputed border, close to the frontline between Azerbaijani and Armenian troops in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh territory. The helicopter was hit by an Igla-S shoulder-launched missile fired by Azerbaijani soldiers while flying at low altitude and crashed, killing all three on board.[85][86][87]

On 2 April 2016, after a clash between Azerbaijani and Armenian forces, a Mil Mi-24 helicopter was destroyed.[88][89]

Other users

Pakistan and Russia on 20 August 2015 finalized a deal for the purchase of four Mi-35M helicopters, a number that is expected to grow. In August 2017 Pakistan received 4 x Mi-35 from Russia.[90][91]

Variants

Operators

Former operators

Accidents

- On 12 August 2012, two Ugandan Army MI-24s flying from Entebbe, Uganda across Kenya to Somalia crashed in rugged terrain in Kenya. They were found two days later, burned out, with no likely survivors from the 10 Ugandan servicemen on board the two helicopters. Another aircraft from the same flight crashed on Mount Kenya and all seven Ugandan servicemen on board were rescued a day later. The aircraft were supporting an African Union force to fight Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Shabaab insurgents in the ongoing Somali Civil War. A Mi-17 transport helicopter, part of the same mission, landed without problems in the eastern Kenyan town of Garissa near the Somali border for a scheduled refuelling stop.[113]

- On 27 December 2009, a Mi-24 of the Sri Lankan Air Force crashed in the Buttala area due to a technical failure. It has been found later that a "power generator failure" warning in the cockpit persuaded pilots to perform protective actions which eventually lead to reducing speed. The actual problem was a failure of the tail rotor drive shaft which was also connected to the power generator and caused the warning. Without tail rotor support, it went out of control and crashed in to the jungle. The crew of two pilots and two gunners were killed.[114][115][116]

Aircraft on display

Mi-24 helicopters can be seen in the following museums:

| Russia | Central Air Force Museum, Monino – Mi-24A, Mi-25 |

| Belgium | Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History, Brussel – Mi-24 |

| Bulgaria | Muzei na aviatsiyata, Plovdiv – Mi-24 |

| Czech Republic | Prague Aviation Museum, Kbely – Mi-24D tactical number 0220 |

| China | Chinese Aviation Museum, Beijing – Mi-24 |

| Germany |

|

| Hungary |

|

| Iran | Sa'ad Abad Museum in Tehran |

| Latvia | Riga Aviation Museum, Riga – Mi-24A tactical number 20 |

| Nicaragua | Airforce Base Augusto C. Sandino International Airport, Managua, Mi-25 tactical number 361 |

| Poland |

|

| South Africa | South African Air Force Museum, Swartkops Air Force Base – One Mi-24A of the Algerian Air Force on display. |

| Slovakia | Military History Museum, Piešťany – Mi-24D tactical number 0100[117] |

| Sri Lanka | |

| Ukraine |

|

| United Kingdom |

|

| United States |

|

| Vietnam |

Specifications (Mi-24)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

Data from Indian-Military.org[122]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2–3: pilot, weapons system officer and technician (optional)

- Capacity: 8 troops or 4 stretchers or 2400 kg (5,291 lb) cargo on an external sling

Performance

- Armament

- Internal guns

-

- flexible 12.7 mm Yakushev-Borzov Yak-B Gatling gun on most variants. Maximum of 1,470 rounds of ammunition.

- fixed twin-barrel GSh-30K autocannon on the Mi-24P. 750 rounds of ammunition.

- flexible twin-barrel GSh-23L autocannon on the Mi-24VP and Mi-24VM. 450 rounds of ammunition.

- PKB passenger compartment window mounted machine guns

- External stores

-

- Total payload is 1,500 kg of external stores.

- Inner hardpoints can carry at least 500 kg

- Outer hardpoints can carry up to 250 kg

- Wing-tip pylons can only carry the 9M17 Phalanga (in the Mi-24A-D) or the 9K114 Shturm complex (in the Mi-24V-F).

- Bomb-load

-

- Bombs within weight range (presumably ZAB, FAB, RBK, ODAB etc.), Up to 500 kg.

- MBD multiple ejector racks (presumably MBD-4 with 4 × FAB-100)

- KGMU2V submunition/mine dispenser pods

- First-generation armament (standard production Mi-24D)

-

- GUV-8700 gunpod (with a 12.7 mm Yak-B + 2 × 7.62 mm GShG-7.62 mm combination or one 30 mm AGS-17)

- UB-32 S-5 rocket launchers

- S-24 240 mm rocket

- 9M17 Fleyta (a pair on each wingtip pylon)

- Second-generation armament (Mi-24V, Mi-24P and most upgraded Mi-24D)

-

- UPK-23-250 gunpod carrying the GSh-23L

- B-8V20 a lightweight long tubed helicopter version of the S-8 rocket launcher

- 9K114 Shturm in pairs on the outer and wingtip pylons

Popular culture

The Mi-24 has appeared in several films and has been a common feature in many video games.

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

- ^ a b "Air-to-Air Defense for Attack Helicopters" (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Day, Dwayne A. "Mi-24 Hind 'Krokodil'". US Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Culhane, Kevin V. (1977). "Student research report: The Soviet attack helicopter" (PDF). DTIC. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d Yefim Gordon & Dmitry Komissarov (2001). Mil Mi-24, Attack Helicopter. Airlife.

- ^ "Mi-28 Replacing Mi-24". Strategy Page. 1 October 2007.

- ^ "Russia's Air Force to Replace Combat Helicopters by 2015". Kommersant. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Halberstadt, Hans (1994). "Red Star Fighters & Ground Attack". Windrow & Greene. pp. 85, 88. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mil Mi-24 Helicopter – Military Forces". Military Forces. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ a b Gordon, Yefim; Komissarov, Dmitry (2001). Mil Mi-24 Hind, Attack Helicopter. Airlife.

- ^ "Rotorcraft World Records: List of records established by the 'A-10'". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Archived from the original on 23 July 2003. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rotorcraft World Records: History of Rotorcraft World Records". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper, Tom. "Ogaden War, 1977–1978". Air Combat Information Group. Archived from the original on 7 January 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ Grau, Lester W. The Bear Went Over the Mountain: Soviet Combat Tactics in Afghanistan. National Defense University Press, 1996.

- ^ John Pike. "Russian Army Equipment". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ "Soviet Air Power:". Airpower.au.af.mil. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "The Costs of Soviet Involvement in Afghanistan". Office of Soviet Analysis

- ^ a b c d e f Goebel, Greg (1 April 2009). "Hind Variants / Soviet Service". Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 18-JUL-1979 Mil Mi-24A". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Afghanistan – Air force in local wars". Skywar.ru. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Yakubovich, Nikolay. Boevye vertolety Rossii. Ot "Omegi" do "Alligatora" (Russia's combat helicopters. From Omega to Alligator). Moscow, Yuza & Eksmo, 2010, ISBN 978-5-699-41797-1, pp.164–173.

- ^ Silverstein, Ken (2 October 2001). "Stingers, Stingers, Who's Got the Stingers?". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ In Syria, hints of Soviet helicopter tactics from Afghanistan – Washingtonpost.com, 8 October 2015

- ^ Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad (9 September 2003). "I Persian Gulf War: Iraqi Invasion of Iran, September 1980". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ a b c Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad (9 September 2003). "Fire in the Hills: Iranian and Iraqi Battles of Autumn 1982". Air Combat Information Group. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Goebel, Greg (16 September 2012). "Hind in Foreign Service / Hind Upgrades / Mi-28 Havoc". The Mil Mi-24 Hind & Mi-28 Havoc. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Mi-24". Wings Palette. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ "Mil Mi-24". Aerospaceweb.org. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ a b Cooper, Tom (29 October 2003). "Sri Lanka, since 1971". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ Johns, Dave. "Suppression of the 1991 Uprising". The Crimes of Saddam Hussein. PBS. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Brew, Nigel (16 June 2003). "Behind the Mujahideen-e-Khalq (MeK)". Parliament of Australia. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Corcoran, Mark (28 September 2000). "Gunship for Hire". Foreign Correspondent. ABC News (Australia).

- ^ Cooper, Tom; Chick, Court "Skyler" (5 August 2004). "Sierra Leone, 1990–2002". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ Fowler, Will (10 April 2010). ellis Certain Death in Sierra Leone: The SAS and Operation Barras 2000. Raid 10. Osprey Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 9781846038501.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Berger, Heinz (July 2011). "Croatian Air Force at 20". Combat Aircraft. 12 (7): 83. ISSN 2041-7470.

- ^ Pashin, Alexander. "Russian Army Operations and Weaponry During Second Military Campaign in Chechnya". Moscow Defense Brief. Archived from the original on 1 May 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Los Mi-25 de la FAP". Geocities.ws. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Arequipa: Presentan los helicópteros MI – 25 para la lucha en el VRAEM". Perú.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Ofensiva Mayor en el VRAE". YouTube. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "PeruDefensa.com – PeruDefensa.com's Photos – Facebook". Facebook.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Cooper, Tom. "Peru vs. Ecuador; Alto Cenepa War, 1995". ACIG.org. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "Government Revenue from Oil and Expenditures on Arms". Sudan, Oil, and Human Rights. Human Rights Watch. September 2003. ISBN 978-1-56432-291-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper, Tom (26 November 2004). "Mil-Helicopters in World-Wide Service, Part 1". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ Cooper, Tom; Weinert, Pit (2 September 2003). "Zaire/DR Congo since 1980". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ Datt, Gautam (27 July 2005). "More troops may go to Congo". DefenceIndia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cooper, Tom (30 November 2003). "Macedonia, 2001". Air Combat Information Group.

- ^ Bridgland, Fred (8 November 2004). "Ivory Coast descends into chaos and war". The Scotsman. UK. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008.

- ^ "First American flies Mi-35 HIND in combat". Af.mil. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ Radin, CJ (July 2009). "Afghan National Security Forces Order of Battle, Afghan National Army Air Corps (ANAAC)" (PDF). The Long War Journal. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ "Taliban Attack US Embassy, Other Kabul Buildings". Associated Press. 13 September 2011.

- ^ "Mil Mi-24 Ghazni, Afghanistan". Helihub – the Helicopter Industry Data Source. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "Why India Transferred Attack Helicopters to Afghanistan". The Diplomat. 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Indian multi-role helicopters Mi-35 made a difference in Afghanistan: US General John Campbell". DNA News. 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Śmigłowce Mi-24 w PKW w Iraku" (in Polish). Ministerstwo Obrony Narodowej. 24 January 2005. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Helicopter shot down in Somalia". BBC. 30 March 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Tanks of August" (PDF). Cast.ru. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ^ Ираклий Аладашвили. Потери ВВС Грузии были минимальными. //Авиация и время. — 2008. — № 6. — С.19.

- ^ Axe, David (4 August 2008). "Chadian helicopter shot down". Demotix. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chad helicopter in 'hard landing' after air attack on rebels". Google. AFP. 12 June 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Options in Libya after UN vote", Strategic Comments, vol. 17, IISS, 2011

- ^ "Libia: Mi-25 destruido en Bengasi", Blogger (JPEG) (in Spanish)

- ^ The Boresight, Blogger, March 2011

- ^ "Libye: point de situation, opération Harmattan", Actualités, Opérations (in French), FR: Défense

- ^ Libyan Conflict, Military Photos, p. 96

- ^ "U.N. helicopters fire on Gbagbo army camp – witnesses". Reuters. 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Syrian forces attack Aleppo". YouTube. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ "To Retrieve Attack Helicopters from Russia, Syria Asks Iraq for Help, Documents Show". ProPublica. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Civil War in Syria (11) : the fall of the airbase of Taftanaz". Military In the Middle East. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "ISIS shoots down a Russian attack helicopter". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Myanmar continues assault on Kachin rebels". AlJazeera. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ "Iraq Starts Taking Delivery of Russian Mi-35 Helicopters". IHS Jane's Archived 28 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "قيادة طيران الجيش تتسلم مروحيات Iraq Receives helicopters mi-35 – YouTube". YouTube. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Al Qaeda's use of old camps sparks tension, violence in Iraq". Al Bawaba. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Iraqi Military Destroys ISIL Camps In Anbar". YouTube. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Kirk Semple And Eric Schmitt (26 October 2014). "Missiles of ISIS May Pose Peril for Aircrews in Iraq". New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ^ Jeremy Binnie. "Iraqi Abrams losses revealed". IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ "The Aviationist " New video shows 12 Russian Mi-24 and Mi-8 helicopters in Crimea". The Aviationist. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 02-MAY-2014 Mil Mi-24P 02 YELLOW". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Two Ukrainian Mi-24s shot down by MANPADS". Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 05-MAY-2014 Mil Mi-24P Hind 29 RED". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "The Aviationist " Impressive Videos of the Ukrainian Air Strikes on Donetsk". The Aviationist. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Forestier, Patrick (17 April 2015). "Offensive contre Boko Haram". Paris Match.

- ^ "Azerbaijan downs Armenian helicopter". BBC News. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 12-NOV-2014 Mil Mi-24". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Ağdamda helikopterin vurulma anı (həqiqi görüntülər)". YouTube. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Hodge, Nathan (2 April 2016). "A Dozen Dead in Heavy Fighting Reported in Nagorno-Karabakh". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ By aida sultanova, associated press. "Azerbaijan Says 12 of Its Soldiers Killed in Fighting – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ "Russia has delivered Mi-35M assault helicopters to Pakistan". Quwa.org. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan Finalizes Hind Deal With Russia". Defense News. 21 August 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd "World Air Forces 2018". Flightglobal Insight. 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2017.(registration required)

- ^ "Интензивни полети и стрелби в рамките на ТУБС "Шабла 2017"" [Intensive flights and shootings within the TUBS "Shabla 2017"] (in Bulgarian). aeropress-bg.com. 16 July 2017.

- ^ Bozinovski, Igor (2 January 2018). "Bulgarian Air Force returns second Mi-24 attack helicopter to service". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "World Air Forces 2015". Flightglobal Insight. 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Bilal, Khan (28 August 2017). "Russia has delivered Mi-35M assault helicopters to Pakistan". Quwa Defence News & Analysis Group. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mladenov Air International May 2011, p. 112.

- ^ Mladenov Air International May 2011, p. 114.

- ^ "Croatia Air Force". aeroflight.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "World's Air Forces 1987 pg. 49". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "Czechoslovak army air force". Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "World's Air Forces 1987 pg. 50". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "landstreitkrafte Mil Mi-24". Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Who Else Used It?". nationalcoldwarexhibition.org. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "96+50 East German Air Force Mil Mi-24 – Planespotters.net Just Aviation". Planespotters.net. 25 April 2010. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hungarian Air Force To Issue Helo Tender". aviationweek.com. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ "Trade Registers". Armstrade.sipri.org. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Slovakia Mi-24 were withdrawn from service" (PDF). Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ SME – Petit Press, a.s. "Vrtuľníky Mi-24 vzlietli v Prešove naposledy". presov.korzar.sme.sk. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "World's Air Forces 1987 pg. 86". flightglobal.com. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ "Soviet Union". nationalcoldwarexhibition.org. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Serbia Paramilitary Police". Aeroflight.co.uk. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Burnt wreckage of two Ugandan army helicopters found". Agence France-Presse via SpaceWar.com, 14 October 2012. Accessed 15 August 2012.

- ^ "MI-24 Attack Helicopter Crashes During Training Mission (updated) | Sri Lanka Air Force". Airforce.lk. 27 November 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ^ Harro Ranter. "ASN Aircraft accident 27-NOV-2009 Mil Mi-24P CH635". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ "Sri Lanka News". Sundayobserver.lk. 29 November 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Military History Museum, Piešťany" foto number 7

- ^ "Eastern European Helicopters." The Helicopter Museum. Retrieved: 10 August 2014.

- ^ "Midland Air Museum - Explore our Exhibits - Aircraft Listing". Midlandairmuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ "Aircraft". Cwam.org. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Russell Military Museum".

- ^ "Mil Mi-24, Mi-25, Mi-35 (Hind) Akbar". Indian-Military.org. 5 October 2009. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Hoyle, Craig (11–17 December 2012). "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International. Vol. 182, no. 5370. pp. 40–64. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Hoyle, Craig (5–11 December 2017). "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International. Vol. 192, no. 5615. pp. 26–57. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Mladenov, Alexander (May 2011). "Fighting Terrorism & Enforcing the Law in Russia". Air International. Vol. 80, no. 5. pp. 108–114. ISSN 0306-5634.

Further reading

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London, UK: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1-904687-84-9.