Napoleon

| Napoleon I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Emperor of the French | |||||

| Reign | 18 May 1804 – 11 April 1814 20 March 1815 – 22 June 1815 | ||||

| Coronation | 2 December 1804 | ||||

| Predecessor | None (himself as First Consul of the French First Republic; previous ruling monarch was Louis XVI) | ||||

| Successor | Louis XVIII (de jure in 1814) | ||||

| King of Italy | |||||

| Reign | 17 March 1805 – 11 April 1814 | ||||

| Coronation | 26 May 1805 | ||||

| Predecessor | None (himself as President of the Italian Republic; previous ruling monarch was Emperor Charles V) | ||||

| Successor | None (kingdom disbanded, next king of Italy was Victor Emmanuel II) | ||||

| Born | 15 August 1769 Ajaccio, Corsica, France | ||||

| Died | 5 May 1821 (aged 51) Longwood, Saint Helena | ||||

| Burial | Les Invalides, Paris, France | ||||

| Spouse | Joséphine de Beauharnais Marie Louise of Austria | ||||

| Issue | Napoleon II | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Bonaparte | ||||

| Father | Carlo Buonaparte | ||||

| Mother | Letizia Ramolino | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (see Napoleon and religions) | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Napoleon Bonaparte (Template:Lang-fr [napoleɔ̃ bɔnɑpaʁt]) (15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the latter stages of the French Revolution and its associated wars in Europe.

As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815. His legal reform, the Napoleonic Code, has been a major influence on many civil law jurisdictions worldwide, but he is best remembered for his role in the wars led against France by a series of coalitions, the so-called Napoleonic Wars. He established hegemony over most of continental Europe and sought to spread the ideals of the French Revolution, while consolidating an imperial monarchy which restored aspects of the deposed Ancien Régime. Due to his success in these wars, often against numerically superior enemies, he is generally regarded as one of the greatest military commanders of all time, and his campaigns are studied at military academies throughout much of the world.[1]

Napoleon was born at Ajaccio in Corsica to parents of noble Italian ancestry. He trained as an artillery officer in mainland France. He rose to prominence under the French First Republic and led successful campaigns against the First and Second Coalitions arrayed against France. He led a successful invasion of the Italian peninsula.

In 1799, he staged a coup d'état and installed himself as First Consul; five years later the French Senate proclaimed him emperor. In the first decade of the 19th century, the French Empire under Napoleon engaged in a series of conflicts—the Napoleonic Wars—that involved every major European power.[1] After a streak of victories, France secured a dominant position in continental Europe, and Napoleon maintained the French sphere of influence through the formation of extensive alliances and the appointment of friends and family members to rule other European countries as French client states.

The Peninsular War and 1812 French invasion of Russia marked turning points in Napoleon's fortunes. His Grande Armée was badly damaged in the campaign and never fully recovered. In 1813, the Sixth Coalition defeated his forces at Leipzig; the following year the Coalition invaded France, forced Napoleon to abdicate and exiled him to the island of Elba. Less than a year later, he escaped Elba and returned to power, but was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815. Napoleon spent the last six years of his life in confinement by the British on the island of Saint Helena. An autopsy concluded he died of stomach cancer. There has been debate about his death, as some scholars have held that he was a victim of arsenic poisoning.

Origins and education

Napoleon was born on 15 August 1769, the second of eight children, in his family's ancestral home Casa Buonaparte, located in the town of Ajaccio, Corsica. This was a year after the island was transferred to France by the Republic of Genoa.[2] He was christened Napoleone di Buonaparte, probably named for an uncle (an older brother, who did not survive infancy, was the first of the sons to be called Napoleone). In his twenties, he adopted the more French-sounding Napoléon Bonaparte.[3][note 1]

The Corsican Buonapartes were descended from minor Italian nobility,[4][5] who had come to Corsica from Liguria in the 16th century.[6] 2012 DNA tests found some of the family's ancestors were from the Caucasus region.[7] The study found haplogroup type E1b1c1*, which originated in Northern Africa circa 1200 BC; the people migrated into the Caucasus and into Europe.[8]

His father Nobile Carlo Buonaparte, an attorney, was named Corsica's representative to the court of Louis XVI in 1777. The dominant influence of Napoleon's childhood was his mother, Letizia Ramolino, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child.[9]

He had an elder brother, Joseph; and younger siblings Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline and Jérôme. A boy and girl were born before Joseph but died in infancy.[10] Napoleon was baptised as a Catholic just before his second birthday, on 21 July 1771 at Ajaccio Cathedral.[11]

Napoleon's noble, moderately affluent background and family connections afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time.[12] In January 1779, Napoleon was enrolled at a religious school in Autun, mainland France, to learn French. In May he was admitted to a military academy at Brienne-le-Château.[13] He spoke with a marked Corsican accent and never learned to spell properly.[14] Napoleon was teased by other students for his accent and applied himself to reading.[15][note 2] An examiner observed that Napoleon "has always been distinguished for his application in mathematics. He is fairly well acquainted with history and geography... This boy would make an excellent sailor."[17][note 3]

On completion of his studies at Brienne in 1784, Napoleon was admitted to the elite École Militaire in Paris. This ended his naval ambition, which had led him to consider an application to the British Royal Navy.[19] He trained to become an artillery officer and, when his father's death reduced his income, was forced to complete the two-year course in one year.[20] He was the first Corsican to graduate from the École Militaire.[20] He had been tested by the famed scientist Pierre-Simon Laplace, whom Napoleon later appointed to the Senate.[21]

Early career

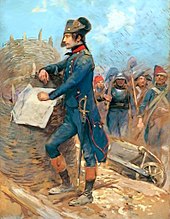

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant in La Fère artillery regiment.[13][note 4] He served on garrison duty in Valence, Drôme and Auxonne until after the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, and took nearly two years' leave in Corsica and Paris during this period. A fervent Corsican nationalist, Bonaparte wrote to the Corsican leader Pasquale Paoli in May 1789:

"As the nation was perishing I was born. Thirty thousand Frenchmen were vomited on to our shores, drowning the throne of liberty in waves of blood. Such was the odious sight which was the first to strike me."[23]

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. He supported the revolutionary Jacobin faction, gained the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Corsican militia, and command over a battalion of volunteers. Despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against a French army in Corsica, he was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792.[24]

He returned to Corsica and came into conflict with Paoli. He had decided to split with France and sabotage a French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena, where Bonaparte was one of the expedition leaders.[25] Bonaparte and his family fled to the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.[26]

Siege of Toulon (1793)

In July 1793, he published a pro-republican pamphlet, Le souper de Beaucaire (Supper at Beaucaire), which gained him the admiration and support of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. With the help of fellow Corsican Antoine Christophe Saliceti, Bonaparte was appointed artillery commander of the republican forces at the siege of Toulon. The city had risen against the republican government and was occupied by British troops.[27]

He adopted a plan to capture a hill where republican guns could dominate the city's harbour and force the British ships to evacuate. The assault on the position, during which Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh, led to the capture of the city. He was promoted to brigadier general at the age of 24. Catching the attention of the Committee of Public Safety, he was put in charge of the artillery of France's Army of Italy.[28]

Whilst waiting for confirmation of this post, Napoleon spent time as inspector of coastal fortifications on the Mediterranean coast near Marseille. He devised plans for attacking the Kingdom of Sardinia as part of France's campaign against the First Coalition.[29] The commander of the Army of Italy, Pierre Jadart Dumerbion, had seen too many generals executed for failing or for having the wrong political views. Therefore, he deferred to the powerful représentants en mission, Augustin Robespierre and Saliceti, who in turn were ready to listen to the freshly promoted artillery general.[30]

Carrying out Bonaparte's plan in the Battle of Saorgio in April 1794, the French army advanced northeast along the Italian Riviera then turned north to seize Ormea in the mountains. From Ormea, they thrust west to outflank the Austro-Sardinian positions around Saorge. As a result, the coastal towns of Oneglia and Loano, as well as the strategic Col de Tende (Tenda Pass), were taken by the French.[31] Later, Augustin Robespierre sent Bonaparte on a mission to the Republic of Genoa to determine that country's intentions towards France.[29]

13 Vendémiaire (1795)

Following the fall of the Robespierres in the July 1794 Thermidorian Reaction, one account alleges that Bonaparte was put under house arrest at Nice for his association with the brothers.[note 5] Napoleon's secretary, Bourrienne, disputed this allegation in his memoirs. According to Bourrienne, jealousy between the Army of the Alps and the Army of Italy (with whom Napoleon was seconded at the time) was responsible.[33] After an impassioned defense in a letter Bonaparte dispatched to representants Salicetti and Albitte, he was acquitted of any wrongdoing.[34]

He was released within two weeks and, due to his technical skills, was asked to draw-up plans to attack Italian positions in the context of France's war with Austria. He also took part in an expedition to take back Corsica from the British, but the French were repulsed by the Royal Navy.[35]

Bonaparate became engaged to Désirée Clary, whose sister, Julie Clary, married Bonaparte's elder brother Joseph; the Clarys were a wealthy merchant family from Marseilles.[36] In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée—a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west central France, on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general—for which the army already had a full quota—and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.[37]

He was moved to the Bureau of Topography of the Committee of Public Safety and sought, unsuccessfully, to be transferred to Constantinople in order to offer his services to the Sultan.[38] During this period, he wrote a romantic novella, Clisson et Eugénie, about a soldier and his lover, in a clear parallel to Bonaparte's own relationship with Désirée.[39] On 15 September, Bonaparte was removed from the list of generals in regular service for his refusal to serve in the Vendée campaign. He faced a difficult financial situation and reduced career prospects.[40]

On 3 October, royalists in Paris declared a rebellion against the National Convention after they were excluded from a new government, the Directory.[41] Paul Barras, a leader of the Thermidorian Reaction, knew of Bonaparte's military exploits at Toulon and gave him command of the improvised forces in defence of the Convention in the Tuileries Palace. Having seen the massacre of the King's Swiss Guard there three years earlier, he realised artillery would be the key to its defence.[13]

He ordered a young cavalry officer, Joachim Murat, to seize large cannons and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795—13 Vendémiaire An IV in the French Republican Calendar. After 1400 royalists died, the rest fled.[41] He had cleared the streets with "a whiff of grapeshot", according to the 19th century historian Thomas Carlyle in The French Revolution: A History.[42]

The defeat of the Royalist insurrection extinguished the threat to the Convention and earned Bonaparte sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new Directory. Murat married one of his sisters and became his brother-in-law; he also served under Napoleon as one of his generals. Bonaparte was promoted to Commander of the Interior and given command of the Army of Italy.[26]

Within weeks he was romantically attached to Barras's former mistress, Joséphine de Beauharnais. They married on 9 March 1796 after he had broken off his engagement to Désirée Clary.[43]

First Italian campaign (1796–97)

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy and led it on a successful invasion of Italy. At the Battle of Lodi he defeated Austrian forces and drove them out of Lombardy.[26] He was defeated at Caldiero by Austrian reinforcements, led by József Alvinczi, though Bonaparte regained the initiative at the crucial Battle of the Bridge of Arcole and proceeded to subdue the Papal States.[44]

Bonaparte argued against the wishes of Directory atheists to march on Rome and dethrone the Pope as he reasoned this would create a power vacuum which would be exploited by the Kingdom of Naples. Instead, in March 1797, Bonaparte led his army into Austria and forced it to negotiate peace.[45] The Treaty of Leoben gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of independence; he also authorised the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark.[46]

His application of conventional military ideas to real-world situations effected his military triumphs, such as creative use of artillery as a mobile force to support his infantry. He referred to his tactics thus: "I have fought sixty battles and I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last."[47]

He was adept at espionage and deception and could win battles by concealment of troop deployments and concentration of his forces on the 'hinge' of an enemy's weakened front. If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two co-operating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other.[48] In this Italian campaign, Bonaparte's army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons and 170 standards.[49] The French army fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battles through superior artillery technology and Bonaparte's tactics.[50]

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics; he founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France.[51] The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned he might become a dictator.[52] Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau to Paris to lead a coup d'état and purge the royalists on 4 September — Coup of 18 Fructidor. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent on Bonaparte who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio, and Bonaparte returned to Paris in December as a hero.[53] He met Talleyrand, France's new Foreign Minister—who would later serve in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon—and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.[26]

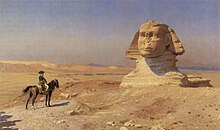

Egyptian expedition (1798–1801)

After two months of planning, Bonaparte decided France's naval power was not yet strong enough to confront the Royal Navy in the English Channel and proposed a military expedition to seize Egypt and thereby undermine Britain's access to its trade interests in India.[26] Bonaparte wished to establish a French presence in the Middle East, with the ultimate dream of linking with a Muslim enemy of the British in India, Tipu Sultan.[54]

Napoleon assured the Directory that "as soon as he had conquered Egypt, he will establish relations with the Indian princes and, together with them, attack the English in their possessions."[55] According to a February 1798 report by Talleyrand: "Having occupied and fortified Egypt, we shall send a force of 15,000 men from Suez to India, to join the forces of Tipu-Sahib and drive away the English."[55] The Directory agreed in order to secure a trade route to India.[56]

In May 1798, Bonaparte was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences. His Egyptian expedition included a group of 167 scientists: mathematicians, naturalists, chemists and geodesists among them; their discoveries included the Rosetta Stone, and their work was published in the Description de l'Égypte in 1809.[57]

En route to Egypt, Bonaparte reached Malta on 9 June 1798, then controlled by the Knights Hospitaller. The two hundred Knights of French origin did not support the Grand Master, Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim, who had succeeded a Frenchman, and made it clear they would not fight against their compatriots. Hompesch surrendered after token resistance, and Bonaparte captured an important naval base with the loss of only three men.[58]

General Bonaparte and his expedition eluded pursuit by the Royal Navy and on 1 July landed at Alexandria.[26] He fought the Battle of Shubra Khit against the Mamluks, Egypt's ruling military caste. This helped the French practice their defensive tactic for the Battle of the Pyramids fought on 21 July, about 24 km from the pyramids. General Bonaparte's forces of 25,000 roughly equalled those of the Mamluks' Egyptian cavalry, but he formed hollow squares with supplies kept safely inside. 29 French[59] and approximately 2,000 Egyptians were killed. The victory boosted the morale of the French army.[60]

On 1 August, the British fleet under Horatio Nelson captured or destroyed all but two French vessels in the Battle of the Nile, and Bonaparte's goal of a strengthened French position in the Mediterranean was frustrated.[61] His army had succeeded in a temporary increase of French power in Egypt, though it faced repeated uprisings.[62] In early 1799, he moved an army into the Ottoman province of Damascus (Syria and Galilee). Bonaparte led these 13,000 French soldiers in the conquest of the coastal towns of Arish, Gaza, Jaffa, and Haifa.[63] The attack on Jaffa was particularly brutal: Bonaparte, on discovering many of the defenders were former prisoners of war, ostensibly on parole, ordered the garrison and 1,400 prisoners to be executed by bayonet or drowning to save bullets.[61] Men, women and children were robbed and murdered for three days.[64]

With his army weakened by disease—mostly bubonic plague—and poor supplies, Bonaparte was unable to reduce the fortress of Acre and returned to Egypt in May.[61] To speed up the retreat, he ordered plague-stricken men to be poisoned.[65] (However, British eyewitness accounts later showed that most of the men were still alive and had not been poisoned.) His supporters have argued this was necessary given the continued harassment of stragglers by Ottoman forces, and indeed those left behind alive were tortured and beheaded by the Ottomans. Back in Egypt, on 25 July, Bonaparte defeated an Ottoman amphibious invasion at Abukir.[66]

Ruler of France

While in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs through irregular delivery of newspapers and dispatches. He learned France had suffered a series of defeats in the War of the Second Coalition.[67] On 24 August 1799, he took advantage of the temporary departure of British ships from French coastal ports and set sail for France, despite the fact he had received no explicit orders from Paris.[61] The army was left in the charge of Jean Baptiste Kléber.[68]

Unknown to Bonaparte, the Directory had sent him orders to return to ward off possible invasions of French soil, but poor lines of communication meant the messages had failed to reach him.[67] By the time he reached Paris in October France's situation had been improved by a series of victories. The Republic was bankrupt, however, and the ineffective Directory was unpopular with the French population.[69] The Directory discussed Bonaparte's "desertion" but was too weak to punish him.[67]

Bonaparte was approached by one of the Directors, Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, for his support in a coup to overthrow the constitutional government. The leaders of the plot included his brother Lucien; the speaker of the Council of Five Hundred, Roger Ducos; another Director, Joseph Fouché; and Talleyrand. On 9 November—18 Brumaire by the French Republican Calendar—Bonaparte was charged with the safety of the legislative councils, who were persuaded to remove to the Château de Saint-Cloud, to the west of Paris, after a rumour of a Jacobin rebellion was spread by the plotters.[70] By the following day, the deputies had realised they faced an attempted coup. Faced with their remonstrations, Bonaparte led troops to seize control and disperse them, which left a rump legislature to name Bonaparte, Sieyès, and Ducos as provisional Consuls to administer the government.[61]

French Consulate

Though Sieyès expected to dominate the new regime, he was outmanoeuvred by Bonaparte, who drafted the Constitution of the Year VIII and secured his own election as First Consul, and he took up residence at the Tuileries.[71] This made Bonaparte the most powerful person in France.[61]

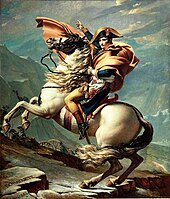

In 1800, Bonaparte and his troops crossed the Alps into Italy, where French forces had been almost completely driven out by the Austrians whilst he was in Egypt.[note 6] The campaign began badly for the French after Bonaparte made strategic errors; one force was left besieged at Genoa but managed to hold out and thereby occupy Austrian resources.[73] This effort, and French general Louis Desaix's timely reinforcements, allowed Bonaparte narrowly to avoid defeat and to triumph over the Austrians in June at the significant Battle of Marengo.[74]

Bonaparte's brother Joseph led the peace negotiations in Lunéville and reported that Austria, emboldened by British support, would not recognise France's newly gained territory. As negotiations became increasingly fractious, Bonaparte gave orders to his general Moreau to strike Austria once more. Moreau led France to victory at Hohenlinden. As a result, the Treaty of Lunéville was signed in February 1801; the French gains of the Treaty of Campo Formio were reaffirmed and increased.[74]

Temporary peace in Europe

Both France and Britain had become tired of war and signed the Treaty of Amiens in October 1801 and March 1802. This called for the withdrawal of British troops from most colonial territories it had recently occupied.[73] The peace was uneasy and short-lived. Britain did not evacuate Malta as promised and protested against Bonaparte's annexation of Piedmont and his Act of Mediation, which established a new Swiss Confederation, though neither of these territories were covered by the treaty.[75] The dispute culminated in a declaration of war by Britain in May 1803, and he reassembled the invasion camp at Boulogne.[61]

Bonaparte faced a major setback and eventual defeat in the Haitian Revolution. By the Law of 20 May 1802 Bonaparte re-established slavery in France's colonial possessions, where it had been banned following the Revolution.[76] Following a slave revolt, he sent an army to reconquer Saint-Domingue and establish a base. The force was, however, destroyed by yellow fever and fierce resistance led by Haitian generals Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines.[note 7] Faced by imminent war against Britain and bankruptcy, he recognised French possessions on the mainland of North America would be indefensible and sold them to the United States—the Louisiana Purchase—for less than three cents per acre (7.4 cents per hectare).[78]

French Empire

Napoleon faced royalist and Jacobin plots as France's ruler, including the Conspiration des poignards (Dagger plot) in October 1800 and the Plot of the Rue Saint-Nicaise (also known as the infernal machine) two months later.[79] In January 1804, his police uncovered an assassination plot against him which involved Moreau and which was ostensibly sponsored by the Bourbon former rulers of France. On the advice of Talleyrand, Napoleon ordered the kidnapping of Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien, in violation of neighbouring Baden's sovereignty. After a secret trial the Duke was executed, even though he had not been involved in the plot.[80]

Napoleon used the plot to justify the re-creation of a hereditary monarchy in France, with himself as emperor, as a Bourbon restoration would be more difficult if the Bonapartist succession was entrenched in the constitution.[81] Napoleon crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I on 2 December 1804 at Notre Dame de Paris and then crowned Joséphine Empress. Ludwig van Beethoven, a long-time admirer, was disappointed at this turn towards imperialism and scratched his dedication to Napoleon from his 3rd Symphony.[81] The story that Napoleon seized the crown out of the hands of Pope Pius VII during the ceremony to avoid his subjugation to the authority of the pontiff is apocryphal; the coronation procedure had been agreed in advance.[note 8][citation needed]

At Milan Cathedral on 26 May 1805, Napoleon was crowned King of Italy with the Iron Crown of Lombardy. He created eighteen Marshals of the Empire from amongst his top generals, to secure the allegiance of the army.

War of the Third Coalition

Great Britain broke the Peace of Amiens and declared war on France in May 1803. Napoleon set up a camp at Boulogne-sur-Mer to prepare for an invasion of Britain. By 1805, Britain had convinced Austria and Russia to join a Third Coalition against France. Napoleon knew the French fleet could not defeat the Royal Navy in a head-to-head battle and planned to lure it away from the English Channel.[82]

The French Navy would escape from the British blockades of Toulon and Brest and threaten to attack the West Indies, thus drawing off the British defence of the Western Approaches, in the hope a Franco-Spanish fleet could take control of the channel long enough for French armies to cross from Boulogne and invade England.[82] However, after defeat at the naval Battle of Cape Finisterre in July 1805 and Admiral Villeneuve's retreat to Cadiz, invasion was never again a realistic option for Napoleon.[83]

As the Austrian army marched on Bavaria, he called the invasion of Britain off and ordered the army stationed at Boulogne, his Grande Armée, to march to Germany secretly in a turning movement—the Ulm Campaign. This encircled the Austrian forces about to attack France and severed their lines of communication. On 20 October 1805, the French captured 30,000 prisoners at Ulm, though the next day Britain's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar meant the Royal Navy gained control of the seas.[84]

Six weeks later, on the first anniversary of his coronation, Napoleon defeated Austria and Russia at Austerlitz. This ended the Third Coalition, and he commissioned the Arc de Triomphe to commemorate the victory. Austria had to concede territory; the Peace of Pressburg led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and creation of the Confederation of the Rhine with Napoleon named as its Protector.[84]

Napoleon would go on to say, "The battle of Austerlitz is the finest of all I have fought."[85] Frank McLynn suggests Napoleon was so successful at Austerlitz he lost touch with reality, and what used to be French foreign policy became a "personal Napoleonic one".[86] Vincent Cronin disagrees, stating Napoleon was not overly ambitious for himself, that "he embodied the ambitions of thirty million Frenchmen".[87]

Middle-Eastern alliances

Even after the failed campaign in Egypt, Napoleon continued to entertain a grand scheme to establish a French presence in the Middle East.[54] An alliance with Middle-Eastern powers would have the strategic advantage of pressuring Russia on its southern border. From 1803, Napoleon went to considerable lengths to try to convince the Ottoman Empire to fight against Russia in the Balkans and join his anti-Russian coalition.[88]

Napoleon sent General Horace Sebastiani as envoy extraordinary, promising to help the Ottoman Empire recover lost territories.[88] In February 1806, following Napoleon's victory at Austerlitz and the ensuing dismemberment of the Habsburg Empire, the Ottoman Emperor Selim III finally recognised Napoleon as Emperor, formally opting for an alliance with France "our sincere and natural ally", and war with Russia and England.[89]

A Franco-Persian alliance was also formed, from 1807 to 1809, between Napoleon and the Persian Empire of Fat′h-Ali Shah Qajar, against Russia and Great Britain. The alliance ended when France allied with Russia and turned its focus to European campaigns.[54]

War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition was assembled in 1806, and Napoleon defeated Prussia at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt in October.[90] He marched against advancing Russian armies through Poland and was involved in the bloody stalemate of the Battle of Eylau on 6 February 1807.[91]

After a decisive victory at Friedland, he signed the Treaties of Tilsit; one with Tsar Alexander I of Russia which divided the continent between the two powers; the other with Prussia which stripped that country of half its territory. Napoleon placed puppet rulers on the thrones of German states, including his brother Jérôme as king of the new Kingdom of Westphalia. In the French-controlled part of Poland, he established the Duchy of Warsaw with King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony as ruler.[92]

With his Milan and Berlin Decrees, Napoleon attempted to enforce a Europe-wide commercial boycott of Britain called the Continental System. This act of economic warfare did not succeed, as it encouraged British merchants to smuggle into continental Europe, and Napoleon's exclusively land-based customs enforcers could not stop them.[93]

Peninsular War

Portugal did not comply with the Continental System, so in 1807 Napoleon invaded with the support of Spain. Under the pretext of a reinforcement of the Franco-Spanish army occupying Portugal, Napoleon invaded Spain as well, replaced Charles IV with his brother Joseph and placed his brother-in-law Joachim Murat in Joseph's stead at Naples. This led to resistance from the Spanish army and civilians in the Dos de Mayo Uprising.[94]

In Spain, Napoleon faced a new type of war, coined since then as guerrilla, in which the local population, inspired by religion and patriotism, was heavily involved. This early type of national war consisted of various types of low intensity fighting (ambushes, sabotage, uprisings...) and open support to the Spanish-allied regular armies.

Following a French retreat from much of the country, Napoleon took command and defeated the Spanish Army. He retook Madrid, then outmanoeuvred a British army sent to support the Spanish and drove it to the coast.[95] Before the Spanish population had been fully subdued, Austria again threatened war, and Napoleon returned to France.[96]

The costly and often brutal Peninsular War continued in Napoleon's absence; in the second Siege of Zaragoza most of the city was destroyed and over 50,000 people perished.[97] Although Napoleon left 300,000 of his finest troops to battle Spanish guerrillas as well as British and Portuguese forces commanded by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, French control over the peninsula again deteriorated.[98]

Following several allied victories, the war concluded after Napoleon's abdication in 1814.[99] Napoleon later described the Peninsular War as central to his final defeat, writing in his memoirs "That unfortunate war destroyed me... All... my disasters are bound up in that fatal knot."[100]

War of the Fifth Coalition and remarriage

In April 1809, Austria abruptly broke its alliance with France, and Napoleon was forced to assume command of forces on the Danube and German fronts. After early successes, the French faced difficulties in crossing the Danube and suffered a defeat in May at the Battle of Aspern-Essling near Vienna. The Austrians failed to capitalise on the situation and allowed Napoleon's forces to regroup. He defeated the Austrians again at Wagram, and the Treaty of Schönbrunn was signed between Austria and France.[101]

Britain was the other member of the coalition. In addition to the Iberian Peninsula, the British planned to open another front in mainland Europe. However, Napoleon was able to rush reinforcements to Antwerp, owing to Britain's inadequately organised Walcheren Campaign.[102]

He concurrently annexed the Papal States because of the Church's refusal to support the Continental System; Pope Pius VII responded by excommunicating the emperor. The pope was then abducted by Napoleon's officers, and though Napoleon had not ordered his abduction, he did not order Pius' release. The pope was moved throughout Napoleon's territories, sometimes while ill, and Napoleon sent delegations to pressure him on issues including agreement to a new concordat with France, which Pius refused. In 1810 Napoleon married Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, following his divorce of Joséphine; this further strained his relations with the Church, and thirteen cardinals were imprisoned for non-attendance at the marriage ceremony.[103] The pope remained confined for 5 years and did not return to Rome until May 1814.[104]

In November 1810, Napoleon consented to the ascent to the Swedish throne of Bernadotte, one of his marshals, with whom Napoleon had always had strained relations. Napoleon had indulged Bernadotte's indiscretions because he was married to Désirée Clary, his former fiancée and sister of the wife of his brother Joseph. Napoleon came to regret accepting this appointment when Bernadotte later allied Sweden with France's enemies.[105]

Invasion of Russia

The Congress of Erfurt sought to preserve the Russo-French alliance, and the leaders had a friendly personal relationship after their first meeting at Tilsit in 1807.[106] By 1811, however, tensions had increased and Alexander was under pressure from the Russian nobility to break off the alliance. An early sign the relationship had deteriorated was the Russian's virtual abandonment of the Continental System, which led Napoleon to threaten Alexander with serious consequences if he formed an alliance with Britain.[107]

By 1812, advisers to Alexander suggested the possibility of an invasion of the French Empire and the recapture of Poland. On receipt of intelligence reports on Russia's war preparations, Napoleon expanded his Grande Armée to more than 450,000 men.[108] He ignored repeated advice against an invasion of the Russian heartland and prepared for an offensive campaign; on 23 June 1812 the invasion commenced.[109]

In an attempt to gain increased support from Polish nationalists and patriots, Napoleon termed the war the Second Polish War—the First Polish War had been the Bar Confederation uprising by Polish nobles against Russia in 1768. Polish patriots wanted the Russian part of Poland to be joined with the Duchy of Warsaw and an independent Poland created. This was rejected by Napoleon, who stated he had promised his ally Austria this would not happen. Napoleon refused to manumit the Russian serfs because of concerns this might provoke a reaction in his army's rear. The serfs later committed atrocities against French soldiers during France's retreat.[110]

The Russians avoided Napoleon's objective of a decisive engagement and instead retreated deeper into Russia. A brief attempt at resistance was made at Smolensk in August; the Russians were defeated in a series of battles, and Napoleon resumed his advance. The Russians again avoided battle, although in a few cases this was only achieved because Napoleon uncharacteristically hesitated to attack when the opportunity arose. Owing to the Russian army's scorched earth tactics, the French found it increasingly difficult to forage food for themselves and their horses.[111]

The Russians eventually offered battle outside Moscow on 7 September: the Battle of Borodino resulted in approximately 44,000 Russian and 35,000 French dead, wounded or captured, and may have been the bloodiest day of battle in history up to that point in time.[112] Although the French had won, the Russian army had accepted, and withstood, the major battle Napoleon had hoped would be decisive. Napoleon's own account was: "The most terrible of all my battles was the one before Moscow. The French showed themselves to be worthy of victory, but the Russians showed themselves worthy of being invincible."[113]

The Russian army withdrew and retreated past Moscow. Napoleon entered the city, assuming its fall would end the war and Alexander would negotiate peace. However, on orders of the city's governor Feodor Rostopchin, rather than capitulation, Moscow was burned. After a month, concerned about loss of control back in France, Napoleon and his army left.[114]

The French suffered greatly in the course of a ruinous retreat, including from the harshness of the Russian Winter. The Armée had begun as over 400,000 frontline troops, but in the end fewer than 40,000 crossed the Berezina River in November 1812.[115] The Russians had lost 150,000 in battle and hundreds of thousands of civilians.[116]

War of the Sixth Coalition

There was a lull in fighting over the winter of 1812–13 while both the Russians and the French rebuilt their forces; Napoleon was then able to field 350,000 troops.[117] Heartened by France's loss in Russia, Prussia joined with Austria, Sweden, Russia, Great Britain, Spain, and Portugal in a new coalition. Napoleon assumed command in Germany and inflicted a series of defeats on the Coalition culminating in the Battle of Dresden in August 1813.[118]

Despite these successes, the numbers continued to mount against Napoleon, and the French army was pinned down by a force twice its size and lost at the Battle of Leipzig. This was by far the largest battle of the Napoleonic Wars and cost more than 90,000 casualties in total.[119]

Napoleon withdrew back into France, his army reduced to 70,000 soldiers and 40,000 stragglers, against more than three times as many Allied troops.[120] The French were surrounded: British armies pressed from the south, and other Coalition forces positioned to attack from the German states. Napoleon won a series of victories in the Six Days' Campaign, though these were not significant enough to turn the tide; Paris was captured by the Coalition in March 1814.[121]

When Napoleon proposed the army march on the capital, his marshals decided to mutiny.[122] On 4 April, led by Ney, they confronted Napoleon. Napoleon asserted the army would follow him, and Ney replied the army would follow its generals. Napoleon had no choice but to abdicate. He did so in favour of his son; however, the Allies refused to accept this, and Napoleon was forced to abdicate unconditionally on 11 April.

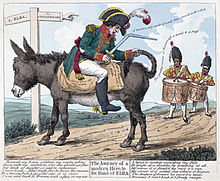

Exile to Elba

The Allied Powers having declared that Emperor Napoleon was the sole obstacle to the restoration of peace in Europe, Emperor Napoleon, faithful to his oath, declares that he renounces, for himself and his heirs, the thrones of France and Italy, and that there is no personal sacrifice, even that of his life, which he is not ready to do in the interests of France.

Done in the palace of Fontainebleau, 11 April 1814.— Act of abdication of Napoleon[123]

In the Treaty of Fontainebleau, the victors exiled him to Elba, an island of 12,000 inhabitants in the Mediterranean, 20 km off the Tuscan coast. They gave him sovereignty over the island and allowed him to retain his title of emperor. Napoleon attempted suicide with a pill he had carried since a near-capture by Russians on the retreat from Moscow. Its potency had weakened with age, and he survived to be exiled while his wife and son took refuge in Austria.[124] In the first few months on Elba he created a small navy and army, developed the iron mines, and issued decrees on modern agricultural methods.[125]

Hundred Days

Separated from his wife and son, who had come under Austrian control, cut off from the allowance guaranteed to him by the Treaty of Fontainebleau, and aware of rumours he was about to be banished to a remote island in the Atlantic Ocean, Napoleon escaped from Elba on 26 February 1815. He landed at Golfe-Juan on the French mainland, two days later.[126]

The 5th Regiment was sent to intercept him and made contact just south of Grenoble on 7 March 1815. Napoleon approached the regiment alone, dismounted his horse and, when he was within gunshot range, shouted, "Here I am. Kill your Emperor, if you wish."[127]

The soldiers responded with, "Vive L'Empereur!" and marched with Napoleon to Paris; Louis XVIII fled. On 13 March, the powers at the Congress of Vienna declared Napoleon an outlaw, and four days later Great Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia bound themselves to each put 150,000 men into the field to end his rule.[128]

Napoleon arrived in Paris on 20 March and governed for a period now called the Hundred Days. By the start of June the armed forces available to him had reached 200,000, and he decided to go on the offensive to attempt to drive a wedge between the oncoming British and Prussian armies. The French Army of the North crossed the frontier into the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, in modern-day Belgium.[129]

Napoleon's forces fought the allies, led by Wellington and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815. Wellington's army withstood repeated attacks by the French and drove them from the field while the Prussians arrived in force and broke through Napoleon's right flank. Napoleon was defeated because he had to fight two armies with one, attacking an army in an excellent defensive position through wet and muddy terrain.

His health that day may have affected his presence and vigour on the field, added to the fact that his subordinates may have let him down. Despite this, Napoleon came very close to clinching victory. Outnumbered, the French army left the battlefield in disorder, which allowed Coalition forces to enter France and restore Louis XVIII to the French throne.

Off the port of Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, after consideration of an escape to the United States, Napoleon formally demanded political asylum from the British Captain Frederick Maitland on HMS Bellerophon on 15 July 1815.[130]

Exile on Saint Helena

Napoleon was imprisoned and then exiled to the island of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean, 1,870 km from the west coast of Africa. In his first two months there, he lived in a pavilion on the Briars estate, which belonged to a William Balcombe. Napoleon became friendly with his family, especially his younger daughter Lucia Elizabeth who later wrote Recollections of the Emperor Napoleon.[131] This friendship ended in 1818 when British authorities became suspicious that Balcombe had acted as an intermediary between Napoleon and Paris and dismissed him from the island.[132]

Napoleon moved to Longwood House in December 1815; it had fallen into disrepair, and the location was damp, windswept and unhealthy. The Times published articles insinuating the British government was trying to hasten his death, and he often complained of the living conditions in letters to the governor and his custodian, Hudson Lowe.[133]

With a small cadre of followers, Napoleon dictated his memoirs and criticised his captors—particularly Lowe. Lowe's treatment of Napoleon is regarded as poor by historians such as Frank McLynn.[134] Lowe exacerbated a difficult situation through measures including a reduction in Napoleon's expenditure, a rule that no gifts could be delivered to him if they mentioned his imperial status, and a document his supporters had to sign that guaranteed they would stay with the prisoner indefinitely.[134]

In 1818, The Times reported a false rumour of Napoleon's escape and said the news had been greeted by spontaneous illuminations in London.[note 9] There was sympathy for him in the British Parliament: Lord Holland gave a speech which demanded the prisoner be treated with no unnecessary harshness.[136] Napoleon kept himself informed of the events through The Times and hoped for release in the event that Holland became prime minister. He also enjoyed the support of Lord Cochrane, who was involved in Chile's and Brazil's struggle for independence and wanted to rescue Napoleon and help him set up a new empire in South America, a scheme frustrated by Napoleon's death in 1821.[137]

There were other plots to rescue Napoleon from captivity including one from Texas, where exiled soldiers from the Grande Armée wanted a resurrection of the Napoleonic Empire in America. There was even a plan to rescue him with a primitive submarine.[138] For Lord Byron, Napoleon was the epitome of the Romantic hero, the persecuted, lonely and flawed genius. The news that Napoleon had taken up gardening at Longwood also appealed to more domestic British sensibilities.[139]

Death

His personal physician, Barry O'Meara, warned the authorities of his declining state of health mainly caused, according to him, by the harsh treatment of the captive in the hands of his "gaoler", Lowe, which led Napoleon to confine himself for months in his damp and wretched habitation of Longwood. O'Meara kept a clandestine correspondence with a clerk at the Admiralty in London, knowing his letters were read by higher authorities: he hoped, in such way, to raise alarm in the government, but to no avail.[140]

In February 1821, Napoleon's health began to fail rapidly, and on 3 May two British physicians, who had recently arrived, attended on him but could only recommend palliatives.[141] He died two days later, after confession, Extreme Unction and Viaticum in the presence of Father Ange Vignali.[141] His last words were, "France, armée, tête d'armée, Joséphine."("France, army, head of the army, Joséphine.")[141]

Napoleon's original death mask was created around 6 May, though it is not clear which doctor created it.[142][note 10] In his will, he had asked to be buried on the banks of the Seine, but the British governor said he should be buried on St. Helena, in the Valley of the Willows. Hudson Lowe insisted the inscription should read "Napoleon Bonaparte"; Montholon and Bertrand wanted the Imperial title "Napoleon" as royalty were signed by their first names only. As a result the tomb was left nameless.[141]

In 1840, Louis Philippe I obtained permission from the British to return Napoleon's remains to France. The remains were transported aboard the frigate Belle-Poule, which had been painted black for the occasion, and on 29 November she arrived in Cherbourg. The remains were transferred to the steamship Normandie, which transported them to Le Havre, up the Seine to Rouen and on to Paris.[144]

On 15 December, a state funeral was held. The hearse proceeded from the Arc de Triomphe down the Champs-Élysées, across the Place de la Concorde to the Esplanade des Invalides and then to the cupola in St Jérôme's Chapel, where it stayed until the tomb designed by Louis Visconti was completed. In 1861, Napoleon's remains were entombed in a porphyry sarcophagus in the crypt under the dome at Les Invalides.[144]

Cause of death

Napoleon's physician, François Carlo Antommarchi, led the autopsy, which found the cause of death to be stomach cancer. Antommarchi did not, however, sign the official report.[145] Napoleon's father had died of stomach cancer though this was seemingly unknown at the time of the autopsy.[146] Antommarchi found evidence of a stomach ulcer, and it was the most convenient explanation for the British who wanted to avoid criticism over their care of the emperor.[141]

In 1955, the diaries of Napoleon's valet, Louis Marchand, appeared in print. His description of Napoleon in the months before his death led Sten Forshufvud to put forward other causes for his death, including deliberate arsenic poisoning, in a 1961 paper in Nature.[147] Arsenic was used as a poison during the era because it was undetectable when administered over a long period. Forshufvud, in a 1978 book with Ben Weider, noted the emperor's body was found to be remarkably well-preserved when moved in 1840. Arsenic is a strong preservative, and therefore this supported the poisoning hypothesis. Forshufvud and Weider observed that Napoleon had attempted to quench abnormal thirst by drinking high levels of orgeat syrup that contained cyanide compounds in the almonds used for flavouring.[147]

They maintained that the potassium tartrate used in his treatment prevented his stomach from expulsion of these compounds and that the thirst was a symptom of the poison. Their hypothesis was that the calomel given to Napoleon became an overdose, which killed him and left behind extensive tissue damage.[147] A 2007 article stated the type of arsenic found in Napoleon's hair shafts was mineral type, the most toxic, and according to toxicologist Patrick Kintz, this supported the conclusion his death was murder.[148]

The wallpaper used in Longwood contained a high level of arsenic compound used for dye by British manufacturers. The adhesive, which in the cooler British environment was innocuous, may have grown mould in the more humid climate and emitted the poisonous gas arsine. This theory has been ruled out as it does not explain the arsenic absorption patterns found in other analyses.[147]

There have been modern studies which have supported the original autopsy finding.[148] Researchers, in a 2008 study, analysed samples of Napoleon's hair from throughout his life, and from his family and other contemporaries. All samples had high levels of arsenic, approximately 100 times higher than the current average. According to these researchers, Napoleon's body was already heavily contaminated with arsenic as a boy, and the high arsenic concentration in his hair was not caused by intentional poisoning; people were constantly exposed to arsenic from glues and dyes throughout their lives.[note 11] 2007 and 2008 studies dismissed evidence of arsenic poisoning, and confirmed evidence of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer as the cause of death.[150]

Reforms

Bonaparte instituted lasting reforms, including higher education, a tax code, road and sewer systems, and established the Banque de France (central bank). He negotiated the Concordat of 1801 with the Catholic Church, which sought to reconcile the mostly Catholic population to his regime. It was presented alongside the Organic Articles, which regulated public worship in France. Later that year, Bonaparte became President of the French Academy of Sciences and appointed Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre its Permanent Secretary.[57]

In May 1802, he instituted the Legion of Honour, a substitute for the old royalist decorations and orders of chivalry, to encourage civilian and military achievements; the order is still the highest decoration in France.[151] His powers were increased by the Constitution of the Year X including: Article 1. The French people name, and the Senate proclaims Napoleon-Bonaparte First Consul for Life.[152] After this he was generally referred to as Napoleon rather than Bonaparte.[22]

Napoleon's set of civil laws, the Code Civil—now often known as the Napoleonic Code—was prepared by committees of legal experts under the supervision of Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès, the Second Consul. Napoleon participated actively in the sessions of the Council of State that revised the drafts. The development of the code was a fundamental change in the nature of the civil law legal system with its stress on clearly written and accessible law. Other codes were commissioned by Napoleon to codify criminal and commerce law; a Code of Criminal Instruction was published, which enacted rules of due process.[153] See Legacy.

Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic code was adopted throughout much of Europe, though only in the lands he conquered, and remained in force after Napoleon's defeat. Napoleon said: "My true glory is not to have won 40 battles...Waterloo will erase the memory of so many victories. ... But...what will live forever, is my Civil Code."[154] The Code still has importance today in a quarter of the world's jurisdictions including in Europe, the Americas and Africa.[155]

Dieter Langewiesche described the code as a "revolutionary project" which spurred the development of bourgeois society in Germany by the extension of the right to own property and an acceleration towards the end of feudalism. Napoleon reorganised what had been the Holy Roman Empire, made up of more than a thousand entities, into a more streamlined forty-state Confederation of the Rhine; this provided the basis for the German Confederation and the unification of Germany in 1871.[156]

The movement toward national unification in Italy was similarly precipitated by Napoleonic rule.[157] These changes contributed to the development of nationalism and the nation state.[158]

Metric system

The official introduction of the metric system in September 1799 was unpopular in large sections of French society, and Napoleon's rule greatly aided adoption of the new standard across not only France but the French sphere of influence. Napoleon ultimately took a retrograde step in 1812 when he passed legislation to introduce the mesures usuelles (traditional units of measurement) for retail trade[159]—a system of measure that resembled the pre-revolutionary units but were based on the kilogram and the metre; for example the livre metrique (metric pound) was 500 g[160] instead of 489.5 g—the value of the livre du roi (the king's pound).[161] Other units of measure were rounded in a similar manner. This however laid the foundations for the definitive introduction of the metric system across Europe in the middle of the 19th century.[162]

Napoleon and religions

Napoleon's baptism was held in Ajaccio on 21 July 1771; he was piously raised and received a Christian education; however, his teachers failed to give faith to the young boy.[163] As an adult, Napoleon was described as a "deist with involuntary respect and fondness for Catholicism."[164] He never believed in a living God; Napoleon's deity was an absent and distant God,[163] but he pragmatically considered organised religions as key elements of social order,[163] and especially Catholicism, whose, according to him, "splendorous ceremonies and sublime moral better act over the imagination of the people than other religions".[163]

Napoleon had a civil marriage with Joséphine de Beauharnais, without religious ceremony, on 9 March 1796. During the campaign in Egypt, Napoleon showed much tolerance towards religion for a revolutionary general, holding discussions with Muslim scholars and ordering religious celebrations, but General Dupuy, who accompanied Napoleon, revealed, shortly after Pope Pius VI's death, the political reasons for such behaviour: "We are fooling Egyptians with our pretended interest for their religion; neither Bonaparte nor we believe in this religion more than we did in Pius the Defunct's one".[note 12] In his memoirs, Bonaparte's secretary Bourienne wrote about Napoleon's religious interests in similar wordings.[166]

His religious opportunism is epitomized in his famous quote: "It is by making myself Catholic that I brought peace to Brittany and Vendée. It is by making myself Italian that I won minds in Italy. It is by making myself a Moslem that I established myself in Egypt. If I governed a nation of Jews, I should reestablish the Temple of Solomon."[167]

Napoleon crowned himself Emperor Napoleon I on 2 December 1804 at Notre Dame de Paris with the benediction of Pope Pius VII. The 1 April 1810, Napoleon religiously married the Austrian princess Marie Louise. In a private discussion with general Gourgaud during his exile on Saint Helena, Napoleon expressed materialistic views on the origin of man,[note 13] and doubted the divinity of Jesus, stating that it is absurd to believe that Socrates, Plato, Muhammad and the Anglicans should be damned for not being Roman Catholics.[note 14] However, Napoleon was anointed by a priest before his death.[170]

Concordat

Seeking national reconciliation between revolutionaries and Catholics, the Concordat of 1801 was signed on 15 July 1801 between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII. It solidified the Roman Catholic Church as the majority church of France and brought back most of its civil status.

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly had taken Church properties and issued the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which made the Church a department of the State, removing it from the authority of the Pope. This caused hostility among the Vendeans towards the change in the relationship between the Catholic Church and the French government. Subsequent laws abolished the traditional Gregorian calendar and Christian holidays.

While the Concordat restored some ties to the papacy, it was largely in favor of the state; the balance of church-state relations had tilted firmly in Napoleon's favour. Now, Napoleon could win favor with the Catholics within France while also controlling Rome in a political sense. Napoleon once told his brother Lucien in April 1801, "Skillful conquerors have not got entangled with priests. They can both contain them and use them."[171] As a part of the Concordat, he presented another set of laws called the Organic Articles.

Religious emancipation

Napoleon emancipated Jews, as well as Protestants in Catholic countries and Catholics in Protestant countries, from laws which restricted them to ghettos, and he expanded their rights to property, worship, and careers. Despite the anti-semitic reaction to Napoleon's policies from foreign governments and within France, he believed emancipation would benefit France by attracting Jews to the country given the restrictions they faced elsewhere.[172]

He stated, "I will never accept any proposals that will obligate the Jewish people to leave France, because to me the Jews are the same as any other citizen in our country. It takes weakness to chase them out of the country, but it takes strength to assimilate them."[173] He was seen as so favourable to the Jews that the Russian Orthodox Church formally condemned him as "Antichrist and the Enemy of God".[174]

Image

Napoleon has become a worldwide cultural icon who symbolises military genius and political power. Martin van Creveld described him as "the most competent human being who ever lived".[175] Since his death, many towns, streets, ships, and even cartoon characters have been named after him. He has been portrayed in hundreds of films and discussed in hundreds of thousands of books and articles.[176]

During the Napoleonic Wars he was taken seriously by the British press as a dangerous tyrant, poised to invade. A nursery rhyme warned children that Bonaparte ravenously ate naughty people; the "bogeyman".[177] The British Tory press sometimes depicted Napoleon as much smaller than average height, and this image persists. Confusion about his height also results from the difference between the French pouce and British inch—2.71 and 2.54 cm respectively; he was about 1.7 metres (5 ft 7 in) tall, average height for the period.[note 15][179]

In 1908 psychologist Alfred Adler cited Napoleon to describe an inferiority complex in which short people adopt an over-aggressive behaviour to compensate for lack of height; this inspired the term Napoleon complex.[180] The stock character of Napoleon is a comically short "petty tyrant" and this has become a cliché in popular culture. He is often portrayed wearing a large bicorne hat with a hand-in-waistcoat gesture—a reference to the 1812 painting by Jacques-Louis David.[181]

Legacy

Warfare

In the field of military organisation, Napoleon borrowed from previous theorists such as Jacques Antoine Hippolyte, Comte de Guibert, and from the reforms of preceding French governments, and then developed much of what was already in place. He continued the policy, which emerged from the Revolution, of promotion based primarily on merit.[182]

Corps replaced divisions as the largest army units, mobile artillery was integrated into reserve batteries, the staff system became more fluid and cavalry returned as an important formation in French military doctrine. These methods are now referred to as essential features of Napoleonic warfare.[182] Though he consolidated the practice of modern conscription introduced by the Directory, one of the restored monarchy's first acts was to end it.[183]

His opponents learned from Napoleon's innovations. The increased importance of artillery after 1807 stemmed from his creation of a highly mobile artillery force, the growth in artillery numbers, and changes in artillery practices. As a result of these factors, Napoleon, rather than relying on infantry to wear away the enemy's defenses, now could use massed artillery as a spearhead to pound a break in the enemy's line that was then exploited by supporting infantry and cavalry. McConachy rejects the alternative theory that growing reliance on artillery by the French army beginning in 1807 was an outgrowth of the declining quality of the French infantry and, later, France's inferiority in cavalry numbers.[184] Weapons and other kinds of military technology remained largely static through the Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, but 18th century operational mobility underwent significant change.[185]

Napoleon's biggest influence was in the conduct of warfare. Antoine-Henri Jomini explained Napoleon's methods in a widely used textbook that influenced all European and American armies.[186] Napoleon was regarded by the influential military theorist Carl von Clausewitz as a genius in the operational art of war, and historians rank him as a great military commander.[187] Wellington, when asked who was the greatest general of the day, answered: "In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon."[188]

Under Napoleon, a new emphasis towards the destruction, not just outmanoeuvring, of enemy armies emerged. Invasions of enemy territory occurred over broader fronts which made wars costlier and more decisive. The political impact of war increased significantly; defeat for a European power meant more than the loss of isolated enclaves. Near-Carthaginian peaces intertwined whole national efforts, intensifying the Revolutionary phenomenon of total war.[189]

Bonapartism

In French political history, Bonapartism has two meanings. The term can refer to people who restored the French Empire under the House of Bonaparte including Napoleon's Corsican family and his nephew Louis. Napoleon left a Bonapartist dynasty which ruled France again; Louis became Napoleon III, Emperor of the Second French Empire and was the first President of France. In a wider sense, Bonapartism refers to a broad centrist or center-right political movement that advocates the idea of a strong and centralised state, based on populism.[190]

Criticism

Napoleon ended lawlessness and disorder in post-Revolutionary France.[191] He was, however, considered a tyrant and usurper by his opponents.[192] His critics charge that he was not significantly troubled when faced with the prospect of war and death for thousands, turned his search for undisputed rule into a series of conflicts throughout Europe and ignored treaties and conventions alike. His role in the Haitian Revolution and decision to reinstate slavery in France's oversea colonies are controversial and have an impact on his reputation.[193]

Napoleon institutionalised plunder of conquered territories: French museums contain art stolen by Napoleon's forces from across Europe. Artefacts were brought to the Musée du Louvre for a grand central museum; his example would later serve as inspiration for more notorious imitators.[194] He was compared to Adolf Hitler most famously by the historian Pieter Geyl in 1947.[195] David G. Chandler, historian of Napoleonic warfare, wrote that, "Nothing could be more degrading to the former and more flattering to the latter."[196]

Critics argue Napoleon's true legacy must reflect the loss of status for France and needless deaths brought by his rule: historian Victor Davis Hanson writes, "After all, the military record is unquestioned—17 years of wars, perhaps six million Europeans dead, France bankrupt, her overseas colonies lost."[197] McLynn notes that, "He can be viewed as the man who set back European economic life for a generation by the dislocating impact of his wars.[192] However, Vincent Cronin replies that such criticism relies on the flawed premise that Napoleon was responsible for the wars which bear his name, when in fact France was the victim of a series of coalitions which aimed to destroy the ideals of the Revolution.[198]

Propaganda and memory

Napoleon's masterful use of propaganda contributed to his rise to power, legitimated his regime, and established his image for posterity. Strict censorship, controlling aspect of the press, books, theater, and art, was only part of his propaganda scheme, aimed at portraying him as bringing desperately wanted peace and stability to France. The propagandistic rhetoric changed in relation to events and the atmosphere of Napoleon's reign, focusing first on his role as a general in the army and identification as a soldier, and moving to his role as emperor and a civil leader. Specifically targeting his civilian audience, Napoleon fostered an important, though uneasy, relationship with the contemporary art community, taking an active role in commissioning and controlling different forms art production to suit his propaganda goals.[199]

Hazareesingh (2004) explores how Napoleon's image and memory is best understood when considered within its socio-political context. It played a key role in collective political defiance of the Bourbon restoration monarchy in 1815–30. People from all walks of life and all areas of France, particularly Napoleonic veterans, drew on the Napoleonic legacy and its connections with the ideals of the 1789 revolution.[200]

Widespread rumors of Napoleon's return from St. Helena and Napoleon as an inspiration for patriotism, individual and collective liberties, and political mobilization manifested themselves in seditious materials, notably displaying the tricolor and rosettes, and subversive activities celebrating anniversaries of Napoleon's life and reign and disrupting royal celebrations, and demonstrated the prevailing and successful goal of the varied supporters of Napoleon to constantly destabilize the Bourbon regime.[200]

Datta (2005) shows that following the collapse of militaristic Boulangism in the late 1880s, the Napoleonic legend was divorced from party politics and revived in popular culture. Concentrating on two plays and two novels from the period—Victorien Sardou's Madame Sans-Gêne (1893), Maurice Barrès's Les Déracinés (1897), Edmond Rostand's L'Aiglon (1900), and André de Lorde and Gyp's Napoléonette (1913) Datta examines how writers and critics of the Belle Epoque exploited the Napoleonic legend for diverse political and cultural ends.[201]

Reduced to a minor character, the new fictional Napoleon was not a world historical figure but an intimate one fashioned by each individual's needs and consumed as popular entertainment. In their attempts to represent the emperor as a figure of national unity, proponents and detractors of the Third Republic used the legend as a vehicle for exploring anxieties about gender and fears about the processes of democratization that accompanied this new era of mass politics and culture.[201]

International Napoleonic Congresses are held regularly and include participation by members of the French and American military, French politicians and scholars from different countries.[202]

Slated for completion in 2014, the Napoleonland theme park near Montereau-Fault-Yonne on the site of Napoleon's victory at the Battle of Montereau, will have attractions detailing his life.

Legacy outside France

Napoleon was responsible for overthrowing multiple Ancien Régime-type monarchies in Europe and spreading the official values of the French Revolution to other countries. In particular, Napoleon's French nationalism had the effect of influencing the development of nationalism elsewhere—often inadvertently. German nationalism of Fichte rose to challenge Napoleon's conquest of Germany. Napoleon was also responsible for inventing the green-white-red tricolour basis of the flag of Italy during the period when Napoleon ruled as King of Italy alongside his position as French Emperor.

The Napoleonic Code is a codification of law including civil, family and criminal law that Napoleon imposed on French-conquered territories. After the fall of Napoleon, not only was Napoleonic Code retained by many such countries including the Netherlands, Belgium, parts of Italy and Germany, but has also been used as the basis of certain parts of law outside Europe including the Dominican Republic, the US state of Louisiana and the Canadian province of Quebec.[203]

The memory of Napoleon in Poland is highly favorable, for his support for independence and opposition to Russia, his legal code, the abolition of serfdom, and the introduction of modern middle class bureaucracies.[204]

A number of leaders have been influenced by Napoleon. Muhammad Ali of Egypt sought alliance with Napoleon's France and sought to modernize Egypt along French governmental lines. In the 20th century, Adolf Hitler admired and emulated Napoleon as a leader and empire-builder, Hitler paid hommage to Napoleon by visiting his tomb after Germany occupied France in World War II.

Marriages and children

Napoleon married Joséphine de Beauharnais in 1796, when he was 26; she was a 32-year-old widow whose first husband had been executed during the Revolution. Until she met Bonaparte, she had been known as "Rose", a name which he disliked. He called her "Joséphine" instead, and she went by this name henceforth. Bonaparte often sent her love letters while on his campaigns.[205] He formally adopted her son Eugène and cousin Stéphanie and arranged dynastic marriages for them. Joséphine had her daughter Hortense marry Napoleon's brother Louis.[206]

Joséphine had lovers, including a Hussar lieutenant, Hippolyte Charles, during Napoleon's Italian campaign.[207] Napoleon learnt the full extent of her affair with Charles while in Egypt, and a letter he wrote to his brother Joseph regarding the subject was intercepted by the British. The letter appeared in the London and Paris presses, much to Napoleon's embarrassment. Napoleon had his own affairs too: during the Egyptian campaign he took Pauline Bellisle Foures, the wife of a junior officer, as his mistress. She became known as "Cleopatra" after the Ancient Egyptian ruler.[208][note 16]

While Napoleon's mistresses had children by him, Joséphine did not produce an heir, possibly because of either the stresses of her imprisonment during the Reign of Terror or an abortion she may have had in her 20s.[210] Napoleon ultimately chose divorce so he could remarry in search of an heir. In March 1810, he married Marie Louise, Archduchess of Austria, and a great niece of Marie Antoinette by proxy; thus he had married into a German royal and imperial family.[211]

They remained married until his death, though she did not join him in exile on Elba and thereafter never saw her husband again. The couple had one child, Napoleon Francis Joseph Charles (1811–1832), known from birth as the King of Rome. He became Napoleon II in 1814 and reigned for only two weeks. He was awarded the title of the Duke of Reichstadt in 1818 and died of tuberculosis aged 21, with no children.[211]

Napoleon acknowledged two illegitimate children: Charles Léon (1806–1881) by Eléonore Denuelle de La Plaigne,[212] and Count Alexandre Joseph Colonna-Walewski (1810–1868) by Countess Marie Walewska.[212] He may have had further unacknowledged illegitimate offspring as well, such as Karl Eugin von Mühlfeld by Victoria Kraus;[101] Hélène Napoleone Bonaparte (1816–1910) by Albine de Montholon; and Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire, whose mother remains unknown.[213]

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

| Monarchical styles of Napoleon I of France | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | My Lord |

| Monarchical styles of Napoleon I of Italy | |

|---|---|

| File:Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Italy (1805-1814) (2).svg | |

| Reference style | His Royal Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Royal Majesty |

| Alternative style | My Lord |

- 18 May 1804 – 11 April 1814: His Imperial Majesty The Emperor of the French

- 17 March 1805 – 11 April 1814: His Imperial and Royal Majesty The Emperor of the French, King of Italy

- 20 March 1815 – 22 June 1815: His Imperial Majesty The Emperor of the French

Full titles

1804–1805

His Imperial Majesty Napoleon I, By the Grace of God and the Constitutions of the Republic, Emperor of the French.

1805–1806

His Imperial and Royal Majesty Napoleon I, By the Grace of God and the Constitutions of the Republic, Emperor of the French, King of Italy.

1806–1809

His Imperial and Royal Majesty Napoleon I, By the Grace of God and the Constitutions of the Republic, Emperor of the French, King of Italy, Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine.

1809–1814

His Imperial and Royal Majesty Napoleon I, By the Grace of God and the Constitutions of the Republic, Emperor of the French, King of Italy, Protector of the Confederation of the Rhine, Mediator of the Helvetic Confederation.

1815

His Imperial Majesty Napoleon I, By the Grace of God and the Constitutions of the Republic, Emperor of the French.

Ancestry

| 16. Giuseppe Maria Buonaparte (1663–1703) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Sebastiano Nicola Buonaparte (1683–1720/60) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Maria Colonna Bozzi (1668–1704) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Giuseppe Maria Buonaparte (1713–1763) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Carlo Tusoli | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Maria Anna Tusoli (1690–1760) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Isabella | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Carlo Maria Buonaparte (1746–1785) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Giuseppe Maria Paravisini | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Maria Saveria Paravisini (1715–bef. 1750) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Angelo Agostino Salineri | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Maria Angela Salineri | |||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Francetta Merezano | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Napoleon I, Emperor of the French and King of Italy (1769–1821) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 24. Giovanni Girolamo Ramolino (1645–?) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Giovanni Agostino Ramolino | |||||||||||||||||||

| 25. Maria Laetitia Boggiano | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Giovanni Geronimo Ramolino (1723–1755) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 26. Andrea Peri (1669–?) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Angela Maria Peri | |||||||||||||||||||

| 27. Maria Maddalena Colonna d'Istria | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Maria Letizia Ramolino (1750–1836) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 28. Giovanni Antonio Pietrasanta | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Giuseppe Maria Pietrasanta | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Angela Maria Pietrasanta (1725–1790) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Maria Josephine Malerba | |||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^ His name was also spelled as Nabulione, Nabulio, Napolionne, and Napulione.[3]

- ^ At Brienne, Napoleon first met Jean-Rémy Moët. who later was a maker of champagne. They became friends, and Napoleon later frequently stayed at Moët's estate. Victorious French armies were known for their indulgence in sabrage: opening a champagne bottle with a sabre.[16]

- ^ Aside from his name, there does not appear to be a connection between him and Napoleon's theorem.[18]

- ^ He was mainly referred to as Bonaparte until he became First Consul for life.[22]

- ^ Some histories state he was imprisoned at the Fort Carré in Antibes but there does not appear to be evidence for this.[32]

- ^ This is depicted in Bonaparte Crossing the Alps by Hippolyte Delaroche and in Jacques-Louis David's imperial Napoleon Crossing the Alps, he is less realistically portrayed on a charger in the latter work.[72]

- ^ Claude Ribbe advances the thesis that the French used gas chambers.[77]

- ^ Napoleon gave the pope a tiara following the ceremony, now referred to as the Napoleon Tiara.

- ^ A custom in which householders place candles in street-facing windows to herald good news.[135]

- ^ It was customary to cast a death mask or mold of a leader. Four genuine death masks of Napoleon are known to exist: one in The Cabildo, a state museum located in New Orleans, one in a Liverpool museum, another in Havana and one in the library of the University of North Carolina.[143]

- ^ The body can tolerate large doses of arsenic if ingested regularly, and arsenic was a fashionable cure-all.[149]

- ^ “Nous trompons les Égyptiens par notre simili attachement à leur religion, à laquelle Bonaparte et nous ne croyons pas plus qu'à celle de Pie le défunt.”[165]