Scouse

| Scouse | |

|---|---|

| Liverpool English, Merseyside English | |

| Native to | United Kingdom |

| Region | Merseyside |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-scouse |

Scouse (/skaʊs/; also, in academic sources, called Liverpool English[1] or Merseyside English)[2][3][4] is an accent and dialect of English found primarily in the Metropolitan county of Merseyside, and closely associated with the city of Liverpool. The accent extends through Birkenhead and all along the North Wales coast, from Flintshire and Wrexham where it is strongest in Wales, to as far west as Prestatyn, Rhyl, Colwyn Bay, Penmaenmawr and Bangor where the surrounding accents have a distinct overlap between Welsh and Scouse English. In some cases Scouse can also be heard in Runcorn and Widnes in Cheshire and Skelmersdale in Lancashire.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

The Scouse accent is highly distinctive, and has little in common with those used in the neighbouring regions of Cheshire and Lancashire.[8] The accent itself is not specific to all of Merseyside, with the accents of residents of St Helens and Southport, for example, more commonly associated with the historic Lancastrian accent.[5][6][7][8][9][11]

North of the Mersey, the accent was primarily confined to Liverpool until the 1950s when slum clearance in the city resulted in migration of the populace into new pre-war and post-war developments in surrounding areas of Merseyside.[10] South of the Mersey, Scouse spread very early to Birkenhead in the 19th century but much later to the rest of the Wirral.[13] The continued development of the city and its urban areas has brought the accent into contact with areas not historically associated with Liverpool such as Prescot, Whiston and Rainhill in Merseyside and Widnes, Runcorn and Ellesmere Port in Cheshire.[10]

Variations within the accent and dialect are noted, along with popular colloquialisms, that show a growing deviation from the historical Lancashire dialect[10] and a growth in the influence of the accent in the wider area.[5][6][7][8][9][11]

Inhabitants of Liverpool can be referred to as Liverpudlians, Liverpolitans or Wackers but are more often described by the colloquialism "Scousers".[14]

Etymology

The word "scouse" is a shortened form of "lobscouse", whose origin is uncertain.[15] It is related to the Norwegian lapskaus, Swedish lapskojs and Danish labskovs and the Low German Labskaus, and refers to a stew commonly eaten by sailors. In the 19th century, poorer people in Liverpool, Birkenhead, Bootle and Wallasey commonly ate "scouse" as it was a cheap dish, and familiar to the families of seafarers. Outsiders tended to call these people "scousers".[16]

In The Lancashire Dictionary of Dialect, Tradition and Folklore, Alan Crosby suggested that the word only became known nationwide with the popularity of the programme Till Death Us Do Part, which featured a Liverpudlian socialist, and a Cockney conservative in regular argument.[17]

Origins

Originally a small fishing village, Liverpool developed as a port, trading particularly with Ireland, and after the 1700s as a major international trading and industrial centre. The city consequently became a melting pot of several languages and dialects, as sailors and traders from different areas, and migrants from other parts of Britain, Ireland and northern Europe, established themselves in the area.

Until the mid-19th century, the dominant local accent was similar to that of neighbouring areas of Lancashire. The influence of Irish and Welsh migrants, combined with European accents, contributed to a distinctive local Liverpool accent.[18] The first reference to a distinctive Liverpool accent was in 1890.[19] Linguist Gerald Knowles suggested that the accent's nasal quality may have derived from poor 19th-century public health, by which the prevalence of colds for many people over a long time resulted in a nasal accent becoming regarded as the norm and copied by others learning the language.[20]

Academic research

The period of early dialect research in Great Britain did little to cover Scouse. The early researcher Alexander John Ellis said that Liverpool and Birkenhead "had no dialect proper", as he conceived of dialects as speech that had been passed down through generations from the earliest Germanic speakers. Ellis did research some locations on the Wirral, but these respondents spoke in traditional Cheshire dialect at the time and not in Scouse.[21] The 1950s Survey of English Dialects recorded traditional Lancastrian dialect from the town of Halewood and found no trace of Scouse influence. The phonetician John C Wells wrote "The Scouse accent might as well not exist" in the context of The Linguistic Atlas of England, which was the Survey's principle output.[22]

The first academic study of Scouse was undertaken by Gerald Knowles at the University of Leeds in 1973. He identified the key problem being that traditional dialect research had focused on developments from a single Ursprache (e.g. West Saxon in the work of AJ Ellis), but Scouse (and many other urban dialects) had resulted from interaction from an unknown aggregate of Ursprachen. He also noted that the means by which Scouse was so easily distinguished from other British accents could not be adequately summarised by traditional phonetic notation.[23]

Phonetics and phonology

The phonemic notation used in this article is based on the set of symbols used by Watson (2007).

Vowels

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| short | long | short | long | ||

| Close | ɪ | iː | ʉː | ʊ | |

| Mid | ɛ | eː | ə | ɔː | |

| Open | a | ɒ | ɑː | ||

- As other Northern English varieties, Scouse lacks the FOOT-STRUT and TRAP-BATH splits, so that words like cut /kʊt/ and pass /pas/ have the same vowels as put /pʊt/ and back /bak/.[26][27] However, some middle-class speakers may use a more RP-like pronunciation, so that cut and pass may be /kʌt/ and /pɑːs/, with the former containing an extra /ʌ/ phoneme that is normally not found in Northern England English. Generally, speakers are not very successful in differentiating between /ʊ/ and /ʌ/ or /a/ and /ɑː/ (only in the BATH words), which often leads to hypercorrection. Utterances such as good luck or black castle may be /ˌɡʌd ˈlʊk/ and /ˌblɑːk ˈkasəl/ instead of RP-like /ˌɡʊd ˈlʌk/, /ˌblak ˈkɑːsəl/ or Scouse /ˌɡʊd ˈlʊk/, /ˌblak ˈkasəl/. Speakers who successfully differentiate between the vowels in good and luck may use a schwa [ə] (best identified phonemically as /ə/, rather than a separate phoneme /ʌ/) instead of an RP-like [ʌ] in the second word, so that they pronounce good luck as /ˌɡʊd ˈlək/.[26]

- Words such as 'book' and 'cook' can be pronounced with the same tenser vowel as in GOOSE, not the one of FOOT. This is true to other towns from the midlands, northern England and Dublin English. The use of a long /uː/ in such words was once used across the whole of Britain, but is now confined to the more traditional accents of Northern England and Scotland.[28]

- Some speakers exhibit the weak vowel merger, so that the unstressed /ɪ/ merges with /ə/. For those speakers, eleven and orange are pronounced /əˈlɛvən/ and /ˈɒrəndʒ/ rather than /ɪˈlɛvən/ and /ˈɒrɪndʒ/.[29]

- In final position, /iː, ʉː/ tend to be somewhat diphthongal [ɪ̈i ~ ɪ̈ɪ, ɪ̈u ~ ɪ̈ʊ]. Sometimes this also happens before /l/ in words such as school [skɪ̈ʊl].[30]

- /ʉː/ is typically central [ʉː] and it may be even fronted to [yː] so that it becomes the rounded counterpart of /iː/.[24]

- The HAPPY vowel is tense [i] and is best analysed as belonging to the /iː/ phoneme.[29][31]

- /eː/ has a huge allophonic variation. Contrary to most other accents of England, the /eː/ vowel covers both SQUARE and NURSE lexical sets. This vowel has unrounded front [ɪː, eː, ëː, ɛː, ɛ̈ː], rounded front [œː], unrounded central [ɘː, əː, ɜː] and rounded central [ɵː] variants. Diphthongs of the [əɛ] and [ɛə] types are also possible.[24][32][33][34][35] For simplicity, this article uses only the symbol ⟨eː⟩. There is not a full agreement on which realisations are the most common:

- According to Wells (1982), they are [ɛ̈ː] and [ëː], with the former being more conservative.[32]

- According to Roca & Johnson (1999), it is [ɘː].[33]

- According to Beal (2004), they are [ɛː] and [ɜː], with the latter being more conservative.[34]

- According to Watson (2007), it is typically a front vowel of the [eː ~ ɛː ~ ɪː] type.[24]

- According to Gimson (2014), it is [œː].[35]

- Middle class speakers may differentiate SQUARE from NURSE by using a front vowel [ɛː] for the former and a central [ɜː] for the latter, much like in RP.[24]

- There is not a full agreement on the phonetic realisation of /ɑː/:

- According to Watson (2007), it is back [ɑː], with front [aː] being a common realisation for some speakers.[24]

- According to Collins & Mees (2013) harvcoltxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCollinsMees2013 (help) and Gimson (2014), it is typically front [aː].[27][36]

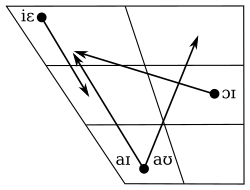

Diphthongs

| Start point |

Endpoint | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [-back] | [+back] | ||

| Close | iɛ (uɛ) | ||

| Mid | eɪ ɔɪ | ɛʉ | |

| Open | aɪ | aʊ | |

- The NEAR vowel /iɛ/ typically has a front second element [ɛ].[25]

- The CURE vowel /uɛ/ often merges with the THOUGHT vowel /ɔː/, so that sure is often /ʃɔː/. When distinct from THOUGHT, this vowel is a diphthong [uɛ] or a disyllabic sequence [ɪuə] or [ɪwə]. The last two realisations are best interpreted phonemically as a sequence /ʉːə/. Variants other than the monophthong [ɔː] are considered to be very conservative.[29]

- The FACE vowel /eɪ/ is typically diphthongal [eɪ], rather than being a monophthong [eː] that is commonly found in other Northern English accents.[37]

- The GOAT vowel /ɛʉ/ has a considerable allophonic variation. Its starting point can be open-mid front [ɛ], close-mid front [e] or mid central [ə] (similarly to the NURSE vowel), whereas its starting point varies between fairly close central [ʉ̞] and a more back [ʊ]. The most typical realisation is [ɛʉ̞], but [ɛʊ, eʉ̞, eʊ, əʉ̞] and an RP-like [əʊ] are also possible.[24] Wells (1982) also lists [oʊ] and [ɔʊ]. According to him, the [eʊ] version has a centralised starting point [ë]. This and variants similar to it sound inappropriately posh in combination with other broad Scouse vowels.[30]

- Older Scouse had a contrastive FORCE vowel /oə/ which is now most commonly merged with THOUGHT/NORTH /ɔː/.[29]

- The PRICE vowel /aɪ/ can be monophthongised to [äː] in certain environments.[24] According to Wells (1982) and Watson (2007), the diphthongal realisation is quite close to the conservative RP norm ([aɪ]),[25][38] but according to Collins & Mees (2013) harvcoltxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCollinsMees2013 (help) it has a rather back starting point ([ɑɪ]).[27]

- The MOUTH vowel /aʊ/ is [aʊ], close to the RP norm.[25][38]

Lexicon and syntax

Irish influences include the pronunciation of the name of the letter H with h-adding; as /heɪtʃ/, and the second person plural (you) as 'youse/yous/use' /juːz/.

The use of me instead of my is also attributed to Irish English influence: for example, "That's me book you got there" for "That's my book you got there".[dubious – discuss] An exception occurs when "my" is emphasised: for example, "That's my book you got there" (and not his (or hers) ).

Other Scouse features in common use include such examples as:

- The use of 'giz' instead of 'give us'. This became famous throughout the UK through Boys from the Blackstuff in 1982.

- The use of the term 'made up' to portray the feeling of happiness or joy in something. For example, 'I'm made up I didn't go out last night'.

- The terms 'sound' and 'boss' are used in many ways. They are used as a positive adjective such as 'it was sound' meaning it was good. It is used to answer questions of our wellbeing, such as 'I'm boss' in reply to 'How are you?' The term can also be used sarcastically in negative circumstances to affirm a type of indifference such as 'I'm dumping you'. The reply 'sound' in this case translates to the sarcastic use of 'good' or to 'yeah fine', 'ok', 'I'm fine about it', 'no problem' etc.

International recognition

Scouse is highly distinguishable from other English dialects. Because of this international recognition, on 16 September, 1996, Keith Szlamp made a request[40] to IANA to make it a recognised Internet dialect. After citing a number of references,[41][42][43][44][45] the application was accepted on 25 May 2000 and now allows Internet documents that use the dialect to be categorised as 'Scouse' by using the language tag "en-Scouse".

Scouse has also become well known as the accent of the international rock band The Beatles.[46] The members of the band are famously from Liverpool;[47] however, their accent is no longer viewed as "Scouse" because of how much Scouse has changed since the "Beatlemania" period of the 1960s.[46]

See also

Other northern English dialects include:

- Geordie (spoken in Newcastle upon Tyne)

- Pitmatic (spoken in Durham and Northumberland)

- Tyke (spoken in Yorkshire)

- Mackem (spoken in Sunderland)

- Mancunian (spoken in Manchester)

- Lancashire dialect and accent, which varies across the county.

- Cumbrian dialect, spoken largely in North and West Cumbria.

References

- ^ Watson (2007:351–360)

- ^ Collins, Beverley S.; Mees, Inger M. (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, pp. 193–194, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- ^ Coupland, Nikolas; Thomas, Alan R., eds. (1990), English in Wales: Diversity, Conflict, and Change, Multilingual Matters Ltd., ISBN 1-85359-032-0

- ^ Howard, Jackson; Stockwell, Peter (2011), An Introduction to the Nature and Functions of Language (2nd ed.), Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 172, ISBN 978-1-4411-4373-0

- ^ a b c Julie Henry (30 March 2008). "Scouse twang spreads beyond Merseyside". The Telegraph.

- ^ a b c "Geordie and Scouse accents on the rise as Britons 'look to protect their sense of identity'". Daily Mail. 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Nick Coligan (29 March 2008). "Scouse accent defying experts and 'evolving'". Liverpool Echo.

- ^ a b c d Dominic Tobin and Jonathan Leake (3 January 2010). "Regional accents thrive against the odds in Britain". The Sunday Times.

- ^ a b c Chris Osuh (31 March 2008). "Scouse accent on the move". Manchester Evening News.

- ^ a b c d Patrick Honeybone. "New-dialect formation in nineteenth century Liverpool: a brief history of Scouse" (PDF). Open House Press.

- ^ a b c Richard Savill (3 January 2010). "British regional accents 'still thriving'". The Telegraph.

- ^ John Mullan (18 June 1999). "Lost Voices". The Guardian.

- ^ Knowles, Gerald (1973). "2.2". Scouse: the urban dialect of Liverpool (PhD). University of Leeds. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Chris Roberts, Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind Rhyme, Thorndike Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-7862-8517-6)

- ^ "lobscouse" at Oxford English Dictionary; retrieved 13 May 2017

- ^ "Scouse" at Oxford English Dictionary; retrieved 13 May 2017

- ^ Alan Crosby, The Lancashire Dictionary of Dialect, Tradition and Folklore, 2000, entry for word Scouser

- ^ Paul Coslett, The origins of Scouse, BBC Liverpool, 11 January 2005. Retrieved 6 February 2015

- ^ Peter Grant, The Scouse accent: Dey talk like dat, don’t dey?, Liverpool Daily Post, 9 August 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2013

- ^ Times Higher Education, Scouse: the accent that defined an era, 29 June 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2015

- ^ Knowles, Gerald (1973). "2.2". Scouse: the urban dialect of Liverpool (PhD). University of Leeds. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Review of the Linguistic Atlas of England, John C Wells, The Times Higher Education Supplement, 1 December 1978

- ^ Knowles, Gerald (1973). "3.2". Scouse: the urban dialect of Liverpool (PhD). University of Leeds. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Watson (2007), p. 358.

- ^ a b c d e Watson (2007), p. 357.

- ^ a b Watson (2007), pp. 357–358.

- ^ a b c Collins & Mees (2013), p. 185. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCollinsMees2013 (help)

- ^ Peter Trudgill, The Dialects of England, page 71, Blackwell, Oxford, 2000

- ^ a b c d Wells (1982), p. 373.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), p. 372.

- ^ Gimson (2014), pp. 92, 115.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), pp. 361, 372.

- ^ a b Roca & Johnson (1999), p. 188.

- ^ a b Beal (2004), p. 125.

- ^ a b Gimson (2014), pp. 118, 138.

- ^ Gimson (2014), p. 125.

- ^ Beal (2004), p. 123.

- ^ a b Wells (1982), pp. 372–373.

- ^ "John Bishop". Desert Island Discs. 24 June 2012. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ "LANGUAGE TAG REGISTRATION FORM". IANA.org. 25 May 2000. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Shaw, Frank; Spiegl, Fritz; Kelly, Stan. Lern Yerself Scouse. Vol. 1: How to Talk Proper in Liverpool. Scouse Press. ISBN 978-0901367013.

- ^ Lane, Linacre; Spiegl, Fritz. Lern Yerself Scouse. Vol. 2: The ABZ of Scouse. Scouse Press. ISBN 978-0901367037.

- ^ Minard, Brian. Lern Yerself Scouse. Vol. 3: Wersia Sensa Yuma?. Scouse Press. ISBN 978-0901367044.

- ^ Spiegl, Fritz; Allen, Ken. Lern Yerself Scouse. Vol. 4: The Language of Laura Norder. Scouse Press. ISBN 978-0901367310.

- ^ Szlamp, K.: The definition of the word 'Scouser', Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ a b "CLEAN AIR CLEANING UP OLD BEATLES ACCENT". abcnews.go.com. 23 February 2002. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. Scouse at AllMusic. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

Bibliography

- Beal, Joan (2004), "English dialects in the North of England: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 113–133, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2013) [First published 2003], Practical Phonetics and Phonology: A Resource Book for Students (3rd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-50650-2

- Gimson, Alfred Charles (2014), Cruttenden, Alan (ed.), Gimson's Pronunciation of English (8th ed.), Routledge, ISBN 9781444183092

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999), A Course in Phonology, Blackwell Publishing

- Watson, Kevin (2007), "Liverpool English" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 37 (3): 351–360, doi:10.1017/s0025100307003180

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, Vol. 2: The British Isles (pp. i–xx, 279–466), Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511611759, ISBN 0-52128540-2

Further reading

- Black, William (2005), The Land that Thyme Forgot, Bantam, p. 348, ISBN 0-593-05362-1

- Tony, Crowley (2012), Scouse: A Social and Cultural History, Liverpool University Press, ISBN 1846318394

- Honeybone, Patrick (2001), "Lenition inhibition in Liverpool English", English Language and Linguistics, 5 (2), Cambridge University Press: 213–249, doi:10.1017/S1360674301000223

- Marotta, Giovanna; Barth, Marlen (2005), "Acoustic and sociolingustic aspects of lenition in Liverpool English" (PDF), Studi Linguistici e Filologici Online, 3 (2): 377–413

- Shaw, Frank; Kelly-Bootle, Stan (1966), Spiegl, Fritz (ed.), How to Talk Proper in Liverpool (Lern Yerself Scouse), Liverpool: Scouse Press, ISBN 0-901367-01-X

External links

- Sounds Familiar: Birkenhead (Scouse) — Listen to examples of Scouse and other regional accents and dialects of the UK on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- 'Hover & Hear' Scouse pronunciations, and compare with other accents from the UK and around the world

- Sound map – Accents & dialects in Accents & Dialects, British Library.

- BBC – Liverpool Local History – Learn to speak Scouse!

- A. B. Z. of Scouse (Lern Yerself Scouse) (ISBN 0-901367-03-6)

- IANA registration form for the

en-scousetag - IETF RFC 4646 — Tags for Identifying Languages (2006)

- Dialect Poems from the English regions

- Visit Liverpool — The official tourist board website to Liverpool

- A Scouser in New York — A syndicated on-air segment that airs on Bolton FM Radio during Kev Gurney's show (7 pm to 10 pm – Saturdays) and Magic 999 during Roy Basnett's Breakfast (6 am to 10 am – Monday to Friday)

- Clean Air Cleaning Up Old Beatles Accent, ABC News