Swaraj

Swaraj (Hindi: स्वराज swa- "self", raj "rule") can mean generally self-governance or "self-rule", and was used synonymously with "home-rule" by Maharishi Dayanand Saraswati and later on by Mahatma Gandhi,[1] but the word usually refers to Gandhi's concept for Indian independence from foreign domination.[2] Swaraj lays stress on governance, not by a hierarchical government, but by self governance through individuals and community building. The focus is on political decentralisation.[3] Since this is against the political and social systems followed by Britain, Gandhi's concept of Swaraj advocated India's discarding British political, economic, bureaucratic, legal, military, and educational institutions.[4] S. Satyamurti, Chittaranjan Das and Motilal Nehru were among a contrasting group of Swarajists who laid the foundation for parliamentary democracy in India.

Although Gandhi's aim of totally implementing the concepts of Swaraj in India was not achieved, the voluntary work organisations which he founded for this purpose did serve as precursors and role models for people's movements, voluntary organisations, and some of the non-governmental organisations that were subsequently launched in various parts of India.[5] The student movement against oppressive local and central governments, led by Jayaprakash Narayan, and the Bhoodan movement, which presaged demands for land reform legislation throughout India, and which ultimately led to India's discarding of the Zamindari system of land tenure and social organisation, were also inspired by the ideas of Swaraj.

Key concepts

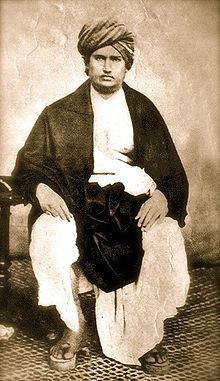

Swami Dayanand Saraswati, founder of the Arya Samaj and a Hindu reformer, defined swaraj as the administration of self or democracy. He said that when God has made people free to do any work as they want, then who were the British to make them slaves in our land? In his view, swaraj was the basis for freedom fighting. Dadabhai Navroji said that he had learnt the word swaraj from the Satyarth Prakash of Saraswati.[citation needed]

Swaraj warrants a stateless society. According to Gandhi, the overall impact of the state on the people is harmful. He called the state a "soulless machine" which, ultimately, does the greatest harm to mankind.[6] The raison d'etre of the state is that it is an instrument of serving the people. But Gandhi feared that in the name of moulding the state into a suitable instrument of serving people, the state would abrogate the rights of the citizens and arrogate to itself the role of grand protector and demand abject acquiescence from them. This would create a paradoxical situation where the citizens would be alienated from the state and at the same time enslaved to it, which, according to Gandhi, was demoralising and dangerous. If Gandhi's close acquaintance with the working of the state apparatus in South Africa and in India strengthened his suspicion of a centralised, monolithic state, his intimate association with the Congress and its leaders confirmed his fears about the corrupting influence of political power and his skepticism about the efficacy of the party systems of power politics (due to which he resigned from the Congress on more than one occasion only to be persuaded back each time) and his study of the British parliamentary systems convinced him that representative democracy was incapable of meting out justice to people.[7]

Gandhi thought it necessary to evolve a mechanism to achieve the twin objectives of empowering the people and 'empowering' the state. It was for this that he developed the two pronged strategy of resistance (to the state) and reconstruction (through voluntary and participatory social action).[citation needed]

Although the word "Swaraj" means self-rule, Gandhi gave it the content of an integral revolution that encompasses all spheres of life: "At the individual level Swaraj is vitally connected with the capacity for dispassionate self-assessment, ceaseless self-purification and growing self-reliance."[8] Politically, swaraj is self-government and not good government (for Gandhi, good government is no substitute for self-government) and it means a continuous effort to be independent of government control, whether it is foreign government or whether it is national. In other words, it is sovereignty of the people based on pure moral authority. Economically, Swaraj means full economic freedom for the toiling millions. And in its fullest sense, Swaraj is much more than freedom from all restraints, it is self-rule, self-restraint, and could be equated with moksha or salvation.[9]

Adopting Swaraj means implementing a system whereby the state machinery is virtually nil, and the real power directly resides in the hands of people. Gandhi said: "Power resides in the people, they can use it at any time."[10] This philosophy rests inside an individual who has to learn to be master of his own self and spreads upwards to the level of his community which must be dependent only on itself. Gandhi said: "In such a state (where swaraj is achieved) everyone is his own ruler. He rules himself in such a manner that he is never a hindrance to his neighbour."[11] He summarised the core principle like this: "It is Swaraj when we learn to rule ourselves."[12]

Gandhi explained his vision in 1946:

Independence begins at the bottom... A society must be built in which every village has to be self sustained and capable of managing its own affairs... It will be trained and prepared to perish in the attempt to defend itself against any onslaught from without... This does not exclude dependence on and willing help from neighbours or from the world. It will be a free and voluntary play of mutual forces... In this structure composed of innumerable villages, there will be ever widening, never ascending circles. Growth will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom. But it will be an oceanic circle whose center will be the individual. Therefore the outermost circumference will not wield power to crush the inner circle but will give strength to all within and derive its own strength from it.[13]

Gandhi was undaunted by the task of implementing such a utopian vision in India. He believed that by transforming enough individuals and communities, society at large would change. He said: "It may be taunted with the retort that this is all Utopian and, therefore not worth a single thought... Let India live for the true picture, though never realisable in its completeness. We must have a proper picture of what we want before we can have something approaching it."[14]

After Gandhi

After Gandhi's assassination Vinoba Bhave formed the Sarva Seva Sangh at the national level and Sarvodya Mandals at the regional level to the carry on integrated village service - with the end purpose of achieving the goal of Swaraj. Two major nonviolent movements for socio-economic and political revolution in India: the Bhoodan movement led by Vinoba Bhave and the Total Revolution movement led by Jayaprakash Narayan were actually formed under the aegis of the ideas of Swaraj. These movements had some success, but due to the socialist tendencies of Nehruvian India were not able to unleash the kind of revolution that was aimed at.

Gandhi's model of Swaraj was almost entirely discarded by the Indian government. He had wanted a system of a classless, stateless direct democracy.[15]

Additionally, modern India has kept in place many aspects of British (and Western) influence, including widespread use of the English language, the common law, industrialisation, liberal democracy, military organisation, and bureaucracy.

Present day

The Aam Aadmi Party was founded in late 2012, by Arvind Kejriwal and some erstwhile activists of India Against Corruption movement, with the aim of empowering people by applying the concept of swaraj enunciated by Gandhi, in the present day context by changing the system of governance.[16]

See also

References

- ^ Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Gandhi, 1909

- ^ What is Swaraj?. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

- ^ Parel, Anthony. Hind Swaraj and other writings of M. K. Gandhi. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 1997.

- ^ What is Swaraj?. Retrieved on March 3, 2007.

- ^ What Swaraj meant to Gandhi. Retrieved on September 17, 2008.

- ^ Jesudasan, Ignatius. A Gandhian theology of liberation. Gujarat Sahitya Prakash: Ananda India, 1987, pp 236-237.

- ^ Hind Swaraj. M.K. Gandhi. Chapter V

- ^ M. K. Gandhi, Young India, June 28, 1928, p. 772.

- ^ "M. K. Gandhi, Young India, December 8, 1920, p.886 (See also Young India, August 6, 1925, p. 276 and Harijan, March 25, 1939, p.64.)

- ^ Jesudasan, Ignatius. A Gandhian theology of liberation. Gujarat Sahitya Prakash: Ananda India, 1987, pp 251.

- ^ Murthy, Srinivas.Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy Letters. Long Beach Publications: Long Beach, 1987, pp 13.

- ^ M. K. Gandhi. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Ahmedabad, Gujarat: Navajivan Publishing House, 1938.

- ^ Murthy, Srinivas.Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy Letters. Long Beach Publications: Long Beach, 1987, pp 189.

- ^ Parel, Anthony. Hind Swaraj and other writings of M. K. Gandhi. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, 1997, pp 189.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Buddhadeva. Evolution of the political philosophy of Gandhi. Calcutta Book House: Calcutta, 1969, pp 479.

- ^ BusinessLine Bureau. "With Swaraj in mind, Kejriwal launches Aam Aadmi Party". The Hindu. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)