Great Renunciation

The Great Renunciation or Great Departure (Sanskrit: mahābhiniṣkramaṇa; Pali: mahābhinikkhamana) [1][2] is the traditional term for the departure of Gautama Buddha (c. 563–c. 483 BCE) from his palace at Kapilavastu to live a life as an ascetic (Sanskrit: śrāmaṇa, Pali: sāmaṇa). It is called the Great Renunciation because it is regarded as a great sacrifice. Most accounts of this event can be found in post-canonical Buddhist texts from several Buddhist traditions, which are the most complete. These are, however, of a more mythological nature than the early texts. They exist in Pāli, Sanskrit and Chinese language.

According to these accounts, at the birth of Prince Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha-to-be, Brahmanas predicted that he would either become a world teacher or a world ruler. To prevent his son from turning to religious life, Prince Siddhārtha's father and rāja of the Śākya clan Śuddhodana did not allow him to see death or suffering, and distracted him with luxury. During his childhood, Prince Siddhārtha had a meditative experience, which made him realize the suffering (Sanskrit: duḥkha, Pali: dukkha) inherent in all existence. He grew up and experienced a comfortable youth. But he continued to ponder about religious questions, and when he was 29 years old, he saw for the first time in his life what became known in Buddhism as the four sights: an old man, a sick person and a corpse, as well as an ascetic that inspired him. Shortly after, Prince Siddhārtha woke up at night and saw his female servants lying in unattractive poses, which shocked the prince. Moved by all the things he had experienced, the prince decided to leave the palace behind in the middle of the night against the will of his father, to live the life of an wandering ascetic, leaving behind his just-born son Rāhula and wife Yaśodharā. He traveled to the river Anomiya with his charioteer Chandaka and horse Kaṇṭhaka, and cut off his hair. Leaving his servant and horse behind, he journeyed into the woods and changed into monk's robes. Later, he met King Bimbisāra, who attempted to share his royal power with the former prince, but the now ascetic Gautama refused.

The story of Prince Siddhārtha's renunciation illustrates the conflict between lay duties and religious life, and shows how even the most pleasurable lives are still filled with suffering. Prince Siddhārtha was moved with a strong religious agitation (Sanskrit and Pali: saṃvega) about the transient nature of life, but believed there was a divine alternative to be found, found in this very life and accessible to the honest seeker. Apart from this sense of religious agitation, he was motivated by a deep empathy with human suffering (Sanskrit and Pali: karuṇā). Traditional accounts say little about the early life of the Buddha, and historical details cannot be known for certain. Historians argue that Siddhārtha Gauatama was indeed born in a wealthy and aristocratic family with a father as a rāja. But the hometown was an oligarchy or republic, not a kingdom, and the prince's wealth and blissful life have been embellished in the traditional texts. The historical basis of Siddhārtha Gautama's life has been affected by his association with the ideal king (cakravartin), inspired by the growth of the Maurya empire a century after he lived. The literal interpretation of the confrontation with the four sights—seeing old age, sickness and death for the first time in his life—is generally not accepted by historians, but seen as symbolical for a growing and shocking existential realization, which may have started in Gautama's early childhood. Later, he may have intentionally given birth to his son Rāhula before his renunciation, to obtain permission from his parents more easily.

The double prediction which occurred shortly after the prince's birth point at two natures within Prince Siddhārtha's person: the struggling human who worked to attain enlightenment, and the divine descendant and cakravartin, which are both important in Buddhist doctrine. The Great Renunciation has been depicted much in Buddhist art. It has influenced ordination rituals in several Buddhist communities, and sometimes such rituals have affected the accounts in turn. A modified version of the Great Renunciation can be found in the legend of the Christian saints Barlaam and Josaphat, one of the most popular and widespread legends in 11th-century Christianity. Although the story describes a victorious Christian king and ascetic, it is imbued with the Buddhist themes and doctrines derived from its original. In modern times, authors such as Edwin Arnold (1832–1904) and Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) have been influenced by the story of the Great Renunciation.

Sources

[edit]| Translations of Great Renunciation | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | Abhiniṣkramaṇa, Mahābhiniṣkramaṇa |

| Pali | Abhinikkhamaṇa |

| Chinese | 出家[3] (Pinyin: chūjiā) |

| Thai | มหาภิเนษกรมณ์ (RTGS: Mahaphinetsakrom) |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Several Early Buddhist Texts such as the Ariyapariyasenā Sutta and the Mahāsaccaka Sutta, as well as sections in the texts on monastic discipline (Sanskrit and Pali: Vinaya), contain fragments about the early life of the Buddha, but not a complete and continuous biography.[4] Nevertheless, even in these fragments, the great departure is often included, especially in Chinese translations of the early texts from the Mahīśāsaka and Dharmaguptaka schools.[5] Later onward, several Buddhist traditions have produced more complete accounts, but these are of a more mythological nature.[6] This includes a more complete biography in the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivādins from the 4th century BC, and several related texts.[7] Sanskrit texts that deal with the life of the Buddha are the Buddhacarita by Aśvaghoṣa (c. 80 – c. 150 CE), the Mahāvastu from the Lokottaravādins (1st century CE), the Lalitavistara from the Sarvāstivādins (1st century CE) and the Saṅghabedavastu.[8][9] There are also translated biographies in Chinese about the life of the Buddha, of which the earliest can be dated between the 2nd and 4th century BC.[7] Many of these include the Chinese word for Great Departure as part of the title.[5] One of the most well-known of these is the Fobenxingji Jing (Sanskrit: Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra), usually translated as the 'Sūtra of the Departure'. [10][note 1]

Sinhalese commentators have composed the Pāli language Jātakanidāna, a commentary to the Jātaka from the 2nd – 3rd century CE, which relates the Buddha's life up until the donation of the Jetavana Monastery.[11] Other important Pāli biographies of later origin are the 12th-century Jinālaṅkāra by Buddharakkhita, the 13th-century Jinacarita by Vanaratana Medhaṅkara, the 18th-century Mālāṅkāra Vatthu and Jinamahānidāna from the 14th - 18th century. However, the most widely distributed biography in Southeast Asia is the late medieval Paṭhamasambodhi, recorded in Pāli and at least eight vernacular languages.[12]

Besides textual sources, information about basic elements of the life of the Buddha can be obtained from early Buddhist art, which is often much older than biographical sources. These artistic depictions were produced in a time when there was no continuous written account of the life of the Buddha available yet.[13]

Accounts

[edit]In Buddhist discourses, the Great Renunciation and Departure are usually mentioned in the life of the Buddha, among several other motifs that cover the religious life of the Buddha-to-be, Prince Siddhārtha Gautama (Pali: Siddhattha Gotama): his first meditation, marriage, palace life, four encounters, life of ease in palace and renunciation, great departure, encounter with hunters, and farewell to his horse Kaṇṭhaka and his charioteer Chandaka (Pali: Channa).[14] In the Tibetan tradition, the Great Departure is mentioned as one of twelve great acts of a Buddha, and the Pāli commentarial tradition includes the Great Departure in a list of thirty deeds and fact that describe Buddhahood.[15]

Birth and early youth

[edit]

Traditional Buddhist texts relate that Prince Siddhārtha Gautama was born with 32 auspicious bodily characteristics. Based on the child's body, as well as his parents' dreams about his birth, eight Brahmin priests and a holy man called Asita made a prediction that he would either become a world teacher or a world ruler (Sanskrit: cakravartin, Pali: cakkavatin),[16][note 2] though one of the Brahmins, Kaundinya, and according to some sources Asita, stated that the child could only become a world teacher.[20] To prevent his son and heir apparent from turning to religious life, Prince Siddhārtha's father and rāja of the Śākya (Pali: Sakya) clan Śuddhodana (Pali: Suddhodana) did not allow him to see death or suffering, and distracted him with luxury to prevent him from worrying and becoming interested in the religious life.[21][22] The early texts and post-canonical biographies describe in much detail how the raja's son lived in great luxury.[23] Śuddhodana provided him with three palaces in Kapilavastu (Pali: Kapilvatthu) for the summer, winter and monsoon, as well as many female attendants to distract him.[24] During his childhood, the prince had his first experience of meditation sitting under a Jambu tree during the Royal Ploughing Ceremony.[25] In some later texts, this is extensively described, explaining how the young prince looked at the animals on the courtyard eating each other, and him realizing the suffering (Sanskrit: duḥkha, Pali: dukkha) inherent in all existence. This caused him to attain meditative absorption. During this meditative experience, the shadow of the tree remained miraculously still, leading the king to come and bow for his own son.[26] The experience would later be used by Gautama after his renunciation, when he discarded austerities and sought another path.[25] It is also a brief summary of what was yet to come: seeing duḥkha and using meditation to find a way to transcend it.[26][note 3]

The four sights

[edit]

When Prince Siddhārtha was 16, he married Yaśodharā (Pali: Yasodharā), just like him of the warrior-noble caste, who is described as perfect in many ways.[29][30] All the while, the texts depict Prince Siddhārtha as the perfect prince, being both a good student, a good warrior and a good husband, to emphasize the glory he would have to leave behind when renouncing the palace life.[31][32] He is described as intelligent, eager to learn and compassionate.[33] But the prince continued to ponder about religious questions, and when he was 29 years old,[note 4] he traveled outside the palace. He then saw—according to some accounts, on separate occasions—four sights for the first time in his life: an old man, a sick person, a corpse and an ascetic. Most traditional texts relate that the sights were brought about through the power of deities, because Śuddhodana had kept all such people away from his son's sight.[35] However, some sources say it was because of chance.[36] Regardless, Prince Siddhārtha learned that everyone, including himself, will have to face old age, sickness and death in the same way. He was shocked by this, and found no happiness in the palace life.[37] The fourth sign was an ascetic who looked at ease, restrained and compassionate.[38][39] The ascetic taught compassion and non-violence and gave the prince hope that there was a way out of suffering, or a way toward wisdom. Therefore, again, the prince discovered what he would later understand more deeply during his enlightenment: duḥkha and the end of duḥkha.[40]

Some time later, Prince Siddhārtha heard the news that a son had been born to him.[41][note 5] The Pāli account claims that when he received the news of his son's birth he replied "rāhulajāto bandhanaṃ jātaṃ", meaning 'A rāhu is born, a fetter has arisen',[44][45] that is, an impediment to the search for enlightenment. Accordingly, the rāja named the child Rāhula,[45] because he did not want his son to pursue a spiritual life as a mendicant.[46] In some versions, Prince Siddhārtha was the one naming his son this way, for being a hindrance on his spiritual path.[47][note 6]

Discontentment

[edit]

After having taken a bath and having been adorned by a barber who was a deity in disguise, Prince Siddhārtha returned to the palace.[50] On his way back, he heard a song from a Kapilavastu woman called Kisā Gotami,[note 7] praising the prince's handsome appearance. The song contained the word nirvṛtā (Pali: nibbuta), which can mean 'blissful, at peace', but also 'extinguished, gone to Nirvana'. The song fascinated him for this reason, and he took it as a sign that it was time for him to seek Nirvana.[53] Foucher describes this as follows:

Marvelous power of a word, which as a crystal dropped in a saturated solution produces crystallization, gave form to all his aspirations still vague and scattered. At that moment, he spontaneously discovered the goal towards his life had turned.[54]

In some versions of the story, he therefore rewarded the woman for her song with a string of pearls. Before Prince Siddhārtha decided to leave the palace, in the morally oriented Lalitavistara he is seen asking his father whether he could leave the city and retire to the forest, but his father said his son that he would give anything for him to stay. Then the prince asked his father whether he could prevent him from growing old, becoming sick or die: the rāja answered he could not.[55][56] Knowing that his son would therefore leave the palace, he gave him his blessing.[57] That night, Prince Siddhārtha woke up in the middle of the night only to find his female servant musicians lying in unattractive poses on the floor, some of them drooling.[56][58] The prince felt as though he was in a cemetery, surrounded by corpses.[59][58] Indologist Bhikkhu Telwatte Rahula notes that there is an irony here, in that the women originally sent by the rāja Śuddhodana to entice and distract the prince from thinking to renounce the worldly life, eventually accomplish just the opposite.[60] Prince Siddhārtha realized that human existence is conditioned by dukkha, and that the human body is of an impermanent and loathsome nature.[61] In another version of the story recorded in the Lalitavistara, the musicians played love songs to the prince, but the deities caused the prince to understand the songs as praising detachment and reminding him of the vow to Buddhahood which he took in previous lives.[58] That night, Prince Siddhārtha dreamt five different dreams, which he would later understood to refer to his future role as a Buddha.[62][63]

Leaving the palace

[edit]

Moved by all the things he had experienced, the prince decided to leave the palace behind in the middle of the night against his father's will, to live the life of an wandering ascetic,[64] leaving behind his son and wife Yaśodharā.[65] Just before he left the palace for the spiritual life, he took one look at his wife Yaśodharā and his newborn child. Fearing his resolve might waver, he resisted to pick up his son and left the palace as planned.[66][67] Some versions of the story say that deities caused the royal family to fall into a slumber, to help the prince escape the palace.[68][57] Because of this, Chandaka and Kaṇṭhaka tried to wake up the royal family, but unsuccessfully.[57] Nevertheless, in some accounts the prince is seen taking leave from his father in a respectful manner, while the latter slept.[59][57] Finally, Chandaka and Kaṇṭhaka both protest against the prince's departure, but the prince went on anyway.[69]

Having finally left the palace, the prince looked back at it once more and took a vow that he would not return until he had attained enlightenment. The texts continue by relating that Prince Siddhārtha was confronted by Mara, the personification of evil in Buddhism, who attempted to tempt him to change his mind and become a cakravartin instead, but to no avail.[57] However, in most versions of the story, as well as visual depictions, there is no such figure.[70] In some versions and depictions, it is not Māra, but Mahānāman (Pali: Mahānāma), father of Yaśodharā, or the local city goddess (representing the distressed city).[71] Regardless, the prince traveled on horse with his charioteer Chandaka, crossing three kingdoms, reaching the river Anomiya (Pali: Anomā). There he gave all his ornaments and robes to Chandaka, shaved his hair and beard and became a religious ascetic.[note 8] Tradition says the prince threw his hairknot in the air, where it was picked up by deities and enshrined in heaven.[73] The brahma deity Ghaṭikāra offered him his robes and other requisites.[74][57] Siddhārtha then comforted Chandaka and sent his charioteer back to the palace to inform his father, while the former prince crossed the river. Chandaka was to tell the king that his son had not chosen this life because of spite or lack of love, nor for "yearning for paradise", but to put an end to birth and death.[75] He had been the witness to the departure from the start up until the transformation into a mendicant, which was exactly what he was required to see, to make the palace understand the transformation was irreversible.[76] The former prince dismissing Chandaka and his horse Kaṇṭhaka is the severing of the last tie that bound him to the world.[77][57] Chandaka left reluctantly; Kaṇṭhaka died because it could not bear the loss.[57][78] (Although in some versions Prince Siddhārtha returned with Chandaka to the palace first.)[79][57]

The former prince then continued his journey into the woods, probably in the area of Malla. According to some accounts, he changed his princely clothes into more simple clothes only now, when he met a woodsman or hunter. The former prince then swapped his clothes with the man, who is in some versions identified with the deity Indra in disguise.[80] Scholar of iconography Anna Filigenzi argues that this exchange indicates Gautama's choice to engage in a more "primitive" kind of society, removed from urban life.[81] Ascetic Gautama then traveled via the Uttarāpatha (Northern Route) passing Rājagṛha, present-day Rajgir.[82] There Gautama met king Bimbisāra, who was much impressed by his demeanor. The king sent a retainer to offer a share to his kingdom, or according to some sources, a position as a minister. The prince refused, however, but promised to return later after his enlightenment.[83]

Meanwhile, when the royal family realized their son and prince was gone, they suffered from the loss. But they were able to deal with it partly by raising grandson Rāhula. As for the prince's jewels, the queen discarded those in a pond to forget the loss.[84]

Discrepancies

[edit]Pali sources state that the renunciation happened on the full moon day of Āsādha (Pali: Asāḷha),[22] whereas sources from the Sarvāstivāda and Dharmaguptaka schools say it happened on Vaiśākha (Pali: Vesakha).[85] There are also textual discrepancies with regard to which day Prince Siddhārtha left, some texts stating the 8th day of the waxing moon, others the 15th, as was already observed by Chinese translator Xuan Zang (c. 602 – 664 CE).[86]

Other early Buddhist textual traditions contain different accounts with regard to Rāhula's birth. The Mahāvastu, as well as Mūlasarvāstivāda texts, relate that Rāhula was conceived on the evening of the renunciation of the prince, and only born six years later, on the day that Prince Siddhārtha achieved enlightenment.[87] Mūlasarvāstivādin and later Chinese texts such as the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra give two types of explanation for the long gestation period: the result of karma in Yaśodharā and Rahula's past lives, and the more naturalistic explanation that Yaśodharā's practice of religious austerities stunted the foetus' growth.[88][89] Buddhist studies scholar John S. Strong notes that these alternative accounts draw a parallel between the quest for enlightenment and Yaśodharā's path to being a mother, and eventually, they both are accomplished at the same time.[90]

In Buddhist doctrine

[edit]

The Great Renunciation functions as a "founding story" of Buddhism.[77][91] Prince Siddhārtha's leaving the palace is traditionally called the Great Renunciation because of the great sacrifice it entails.[92] Archaeologist Alfred Foucher pointed out that the Great Departure marks a point in the biographies of the Buddha from which he was no longer a prince, and no longer asked the deities for assistance: "And as such he found himself in an indifferent world, without guidance or support, confronted with both the noble task of seeking mankind's salvation and the lowly but pressing one of securing his daily bread ..."[59][93] The sacrifice meant that he discarded his royal and caste obligations to affirm the value of spiritual enlightenment.[92] The story of his renunciation illustrates the conflict between lay duties and religious life, and shows how even the most pleasurable lives are still filled with suffering.[94] All traditional sources agree that the prince led a very comfortable life before his renunciation, emphasizing the luxury and comfort he had to leave behind.[25][32] He renounced his life in the palace in order to find "the good" and to find "that most blessed state" which is beyond death.[95] The story of the Great Renunciation is therefore a symbolic example of renunciation for all Buddhist monks and nuns.[96] The Buddha's rejection of the hedonism of the palace life would be reflected in his teaching on the Middle Way, the path between the two extremes of sensual pleasure and self-mortification.[97]

The Buddha's motivation is described as a form of strong religious agitation (Sanskrit and Pali: saṃvega), a sense of fear and disgust that arises when confronted with the transient nature of the world.[98] The Buddha was shocked by the pervasiveness of old age, sickness and death, and spoke about a noble quest of stillness, in which one faces duḥkha as it is and learns from it.[99] The early Buddhist texts state that Prince Siddhārtha's motivation in renouncing the palace life was his existential self-examination, being aware that he would grow old, become sick and die. This awareness would also inspire his teachings later, such as on suffering and the Four Noble Truths.[99] The Buddha has also described his motivation to leave the palace life as a yearning for a life that is "wide open" and as "complete and pure as a polished shell", rather than the palace which is "constricting, crowded and dusty".[100][101] Author Karen Armstrong has suggested that the Buddha's motivation to renounce the worldly life was motivated by a belief in opposites, a feature of the perennial philosophy common in the pre-modern world, that is, that all things in mundane life have their counterpart in divine life. The Buddha looked for the divine counterpart of the suffering of birth, ageing and death—the difference was, though, that the Buddha believed he could realize this counterpart in a "demonstrable reality" in the mundane world, natural to human beings and accessible to the honest seeker.[102] Scholar of religion Torkel Brekke argues that the Buddha's motivation for renunciation was a cognitive dissonance between the pleasurable palace life and the hard reality of age, sickness and death in real life, and a resulting emotional tension.[103]

Generally, Buddhists regard the marriage between Prince Siddhārtha and Princess Yaśodharā as a good one, and the prince as an example of loving-kindness for his wife and son.[104] All Buddhist schools agree that his main motivation in this is a deep empathy with human suffering (Sanskrit and Pali: karuṇā).[105] Though the prince left behind his wife and only son, Buddhists see this lifetime in the context of a path of many lifetimes, through which both the wife and child had taken vows to become a disciple of the Buddha.[106] In of the previous lives of the Buddha, as Sumedha, Yaśodharā and Sumedha are depicted taking a vow to spend the following lifetimes together, on the condition that Yaśodharā would not hinder the Buddha-to-be on his quest.[107] After having become the Buddha, the former Prince Siddhārtha is seen to come back to the palace to teach Yaśodharā and Rāhula and liberate them as well. Eventually Yaśodharā became a nun and attained enlightenment.[108] In the same story, the Buddha is also described teaching his father, and later on, his step-mother Mahāpajāpatī who had raised him.[96]

The Great Renunciation is not only a part of the biography of Gautama Buddha, but is a pattern that can be found in the life of every single Buddha, part of a pre-established blueprint that each Buddha must follow.[109][110]

Scholarly analysis

[edit]Historical

[edit]

Only a little information is given in the texts and discourses about the early life of the Buddha, which contrasts with the abundance of traditional sources about the rest his life, from enlightenment to Parinirvana. Bareau speculated that this may be because the Buddha was disinclined to talk about it, either out of modesty, or because he—and also his leading disciples—did not consider that relating his secular life was sufficiently edifying, as opposed to his religious life.[111] Furthermore, since the accounts about the Buddha's life are filled with mythological embellishments, it may be not be possible to know the exact history, though the accounts are clearly based around historical events.[112]

The site of Siddhārtha Gautama's birth, Kapilavastu, is considered likely to have been historically genuine,[113] though not as commercially important as depicted in later texts.[114] It was an oligarchy or republic, led by a council with alternating rājas, which at the time of Siddhārtha Gautama's birth was Śuddhodana.[115] Śuddhodana was a large landowner belonging to the nobility, and was likely to have had "considerable speaking ability and persuasive powers", which his son Siddhārtha may have inherited.[116] Siddhārtha Gautama was probably born in a wealthy and aristocratic family. Indologist A.K. Warder believed that Siddhārtha Gautama's three palaces were historical, but "... conventional luxury for a wealthy person of the time, whether a warrior or a merchant".[117] However, the palaces were probably houses with multiple levels, not great palaces.[118] Buddhologist André Bareau (1921–1993) argued that the association that is made between the life of the Buddha and that of the cakravartin may have been inspired by the rapid growth of the Maurya Empire in 4th-century BCE India, though it could also be a pre-Buddhist tradition.[119]

Kapilavastu has been identified with both Piprahwā-Ganwārīā, India, and Tilaurākoṭ, Nepal, and scholars are divided as to which site is more likely to have been the historical Kapilavastu.[114][120] During the time of King Ashoka (3rd century BCE), the area was already regarded as the birthplace of the Buddha, judging from the pillar that was erected in Lumbinī, Nepal.[121] With regard to the mentioning of castes in the texts, scholars are in debate as to what extent Kapilavastu was already organized along the lines of the castes of mainland India.[122][123]

Apart from Kapilavastu, nineteen other places featured in the first 29 years of the prince's life were identified by Xuan Zang, who was also a well-known pilgrim. Foucher argued that these places were based on oral recitation traditions surrounding pilgrimages, which now have been lost.[124]

The marriage between Siddhārtha Gautama and Yaśodharā is very likely to be historical. After all, according to Foucher, the monastic and celibate composers of the biographies would have had no good reason to include it if it was not a notable event.[125] Scholars have pointed out that the four sights are not mentioned in the earliest texts in relation to Gautama Buddha, but they are mentioned in one of those texts (Sanskrit: Mahāvadāna Sūtra, Pali: Mahāpadāna Suttanta) with regard to another Buddha, that is, Vipaśyin Buddha (Pali: Vipassī).[126] Nevertheless, the biographies connect this motif with Gautama Buddha from still a relatively early date,[6] and the Mahāvadāna Sūtra also says that these events were repeated in the life of every Buddha.[127] The earliest texts do mention that the Buddha reflected on aging, sickness and death, thereby overcoming the delusion of eternal youth, health and a long life, and deciding to help humanity conquer aging, sickness and death.[128] This part is most likely historical:[129] though it is unlikely that it was possible to raise the young Siddhārtha as "blissfully unaware" as described in traditional texts, it is clear from multiple early texts that confrontation with old age, sickness and death was an important motivation in his renunciation.[130] In the words of Buddhist studies scholar Peter Harvey:

In this way, the texts portray an example of the human confrontation with frailty and mortality; for while these facts are 'known' to us all, a clear realization and acceptance of them often does come as a novel and disturbing insight.[96]

Bareau pointed out that the four sights express the moral shock of confrontation with reality in a legendary form. Moreover, studying Vinaya texts, he found an episode with Prince Siddhārtha as a child, expressing the wish to leave the palace and family life, which Bareau believed was the actual cause for the rāja's concern about his son leaving, rather than the prediction or the four sights. Bareau dated this explanation to the first century after the Buddha or even the Buddha himself (5th century BCE), whereas he dated the four sights and the motif of the blissful youth to the Maurya period (late 4th century BCE) and a century afterwards, respectively. He related these motifs to the association of the Buddha with the cakravartin, which would have made most sense during the rise of the Maurya empire. The connection between deities and previous Buddhas on the one hand, and the four sights on the other hand, Bareau dated to the end of the 3rd century BCE. It was then applied to Gautama Buddha in the 1st century BCE or 1st century CE.[131] Drawing from a theory by philologist Friedrich Weller, Buddhist studies scholar Bhikkhu Anālayo argues, on the other hand, that the four sights might originate in pictorial depictions used in early Buddhism for didactic purposes. These are already mentioned in the early texts and later generations might have taken these depictions literally.[99][132] With regard to the restrictions enforced by Śuddhodana, Schumann said it is probable that the rāja tried to prevent his son from meeting with free-thinking samaṇa and paribbājaka wandering mendicants assembling in nearby parks.[133]

Siddhartha's departure at 29 years old is also seen as historical.[113][134] With regard to Prince Siddhārtha's motivations in renouncing the palace life, at the time of the renunciation, the Śākyans were under military threat by the kingdom of Kosala.[25] The tribal republic as a political unit was gradually being replaced by larger kingdoms.[123] The prince's sensitivity with regard to the future of his clan may have further added to his decision.[25] Scholars have hypothesized that Siddhārtha Gautama conceived Rāhula to please his parents, to obtain their permission for leaving the palace and becoming a mendicant.[135] It was an Indian custom to renounce the world only after the birth of a child or grandchild.[136] Historian Hans Wolfgang Schumann further speculated that Siddhārtha Gautama only conceived a son thirteen years after his marriage, because Yaśodharā initially did not want to bear a child, for fear that he would leave the palace and the throne as soon as the child was conceived.[137] Although many traditional accounts of the Buddha's life relate that Siddhartha left the palace in secret, Early Buddhist Texts clearly state that his parents were aware of his choice, as they are said to have wept at the time their son left them.[121][138] The motif of leaving the palace without the parents' permission might also originate in the early use of didactic canvases, Anālayo argues.[99] The way the former prince renounces the worldly life, by shaving his hair and beard and putting on saffron robes, may have already been a custom in those days, and later became a standard Buddhist custom.[139]

Narrative

[edit]

The Great Renunciation was partly motivated by the First Meditation under the tree when the prince was still a child. This meditation goes hand-in-hand with a shock at the killing of animals which occurred during the ploughing ceremony. Foucher argues that this account may have been affected by the contempt which Indian intellectuals had for agriculture.[140]

Buddhist studies scholar Kate Crosby argues that Siddhārtha conceiving or giving birth to a son before his renunciation functions as a motif to prove that he is the best at each possible path in life: after having tried the life of a father to the fullest, he decides to leave it behind for a better alternative. In early Buddhist India, being a father and bearing a son was seen as a spiritual and religious path as well as that of renouncing one's family, and Siddhārtha's bringing a son in the world before renunciation proves he is capable of both.[141] Buddhist studies scholar John S. Strong hypothesizes that the Mūlasarvāstivāda and Mahāvastu version of the story of the prince conceiving a child on the eve of his departure was developed to prove that the Buddha was not physically disabled in some way. A disability might have raised doubts about the validity of his ordination in monastic tradition.[142]

The motif of the sleeping harem preceding the renunciation is widely considered by scholars to be modeled on the story of Yasa, a guild-master and disciple of the Buddha, who is depicted having a similar experience.[143][144] However, it can also be found in the Hindu epic Rāmayāṇa, and scholar of religion Alf Hiltebeitel, as well as folklorist Mary Brockington believe the Buddhacarita may have borrowed from it. Orientalist Edward Johnston did not want to make any statements about this, however, preferring to wait for more evidence, though he did acknowledge that Aśvaghoṣa "took pleasure" in comparing the Buddha's renunciation with Rāma's leaving for the forest. Hiltebeitel believes that such borrowing is not only about using poetic motifs, but a conscious choice in order to compare the Dharma of the Buddha with the Dharma of Brahmanism. Prince Siddhartha's motivations in renunciation are explained in conversations with his relatives and other figures, alluding explicitly and implicitly to motifs from the Rāmayāṇa.[145]

In his analysis of Indian literature, scholar of religion Graeme Macqueen observes a recurring contrast between the figure of the king and that of the ascetic, who represent external and internal mastery, respectively. This contrast often leads to conflicting roles and aggression in Buddhist stories. In the life of the Buddha, this contrast can be found in the two predictions, in which Prince Siddhārtha will either be a Buddha or an "all-conquering king". Brekke notes that the Buddha chooses to change the self instead of changing the world, as a king would do: he chooses to try to understand the essence of the world and awaken to its truth.[146] Strong argues that the scene of the double prediction after the prince's birth serves to indicate that two aspects of character would continually operate in Prince Siddhārtha's life. On the one hand, that of the king, the cakravartin, the divine descendant from Mahāsammata, and on the other hand, the human being, the person who struggled to find spiritual truth on his path to enlightenment.[147] Buddhist studies scholar Jonathan Silk points out two aspects of Prince Siddhārtha's life narrative that co-exist: one the one hand, that of the nearly perfect being who was born with full awareness, whose life was only one life in a long series, and who was surrounded by miraculous events. On the other hand, the human being who was emotionally shocked by old age and death and grew to full awareness and enlightenment. Both aspects are part of the Buddhist message of liberation.[148]

The horse Kaṇṭhaka has an important role in the accounts about the Great Renunciation. Through several motifs, the accounts establish a close relationship between the Buddha's aspiration to bring living beings to enlightenment on the one hand, and the carrying of Prince Siddhārtha by Kaṇṭhaka on the other hand.[77] In several biographies of the Buddha's life, a shrine is mentioned which was placed at the point where Kaṇṭhaka passed during the Great Departure. Classicist Edward J. Thomas (1869–1958) thought this shrine to be historical.[149] On a similar note, Xuan Zang claimed that the pillar of Aśoka which marks Lumbinī was once decorated at the top with a horse figure, which likely was Kaṇṭhaka, symbolizing the Great Departure. Many scholars have argued that this is implausible, however, saying this horse figure makes little sense from a perspective of textual criticism or art history.[150]

In art and ritual

[edit]

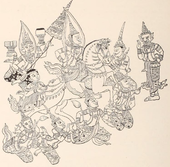

Buddhist art scenes that are often depicted are the four sights,[note 9] the harem and Yaśodharā, the scene in which the prince slips out of the palace, Kaṇṭhaka dying, the lock of hair being picked up by the deity Śakra, and the brahma deity offering the robes and other requisites.[152] The scene in which Prince Siddhārtha leaves the palace riding Kaṇṭhaka is frequently depicted in Buddhist art of South and Southeast Asia. In some depictions, the hooves of the horse are supported by deities to prevent noise and wake up the royal family.[153] In scenes of the Great Departure, there often is a figure depicted standing next to Prince Siddhārtha holding a bow. Some scholars identify him as Vaiśravaṇa (Pali: Vessavaṇa), one of the Four Heavenly Kings in Buddhist cosmology; others identify him as Indra, King of the second heaven in Buddhism, or Bēnzhì, the Chinese god of the cosmos.[154][155] In some depictions, Chandaka clings to the tail of Prince Siddhārtha's horse departing from the palace.[156][57] In Gandhāran art, the Great Renunciation is the most popular episode of the Buddha's biography, together with the Buddha's birth.[157] The scene of the Great Departure is often depicted in such art with the sun and the moon positioned opposite one another, and a Taurus symbol, which scholars of iconography Katsumi Tanabe and Gerd Mevissen argue is indicative of the event happening at midnight during the full moon.[158] Sometimes the Greek moon goddess Selene, or a veiled woman is also used to indicate night time.[159] Gandhāran reliefs connect the departure with the month of Vaiśākha, following the Āgamas.[158] Some Gandhāran frontal depictions of the Great Renunciation are likely to have been influenced by Greco-Bactrian images of the god Helios and the Indian counterpart Surya.[160]

The steps that Prince Siddhārtha goes through when becoming a monk have become a model for ordination rituals for monastics: the cutting of the hair, removal of princely clothes and putting on the monk's robes, the providing of the monastic requisites, etc. Therefore, the founding story of Buddhism essentially becomes the founding story of every Buddhist monk or nun.[77][57] Many Buddhists, for example the Shan people in Myanmar, commemorate Prince Siddhārtha's departure in a procession which takes place during an ordination of a novice, in which the departure is reenacted.[161][162] There are also reenactments of the scene in which Māra tries to block the prince, the role of Māra being played by relatives or friends; or reenactments of the scenes in which deities encourage the prince to leave the palace.[163] On a similar note, in Thai ordinations of monks, the candidate monk-to-be sometimes rides on a horse in procession to the ordination grounds, in memory of Prince Siddhārtha's departure.[164][165][note 10] Relatives play the role of Māra. In Cambodia, similar customs can be found, with participants even playing the role of Indra, of Chandaka, the roles of other deities, and the army of Māra.[167] Strong has hypothesized that some of these ritual reenactments may have influenced the traditional accounts again, such as can be seen in the motif of the deities dressing up Prince Siddhārtha before his departure and tonsure. On a similar note, there is a custom for novices to meditate on their body parts before full ordination to develop detachment. This may have affected the narratives, as can be seen in the motif of the musicians lying naked on the floor before the prince's renunciation.[168] Besides rituals, the biographies may have been influenced by local accounts. These accounts developed at pilgrimage sites dedicated to certain events in the Buddha's life, such as the Great Renunciation. The more official biographies integrated these local accounts connected to cultic life, to authenticate certain Buddha images, as well as the patrons and polities connected to them.[169]

Many Buddhists celebrate the Great Renunciation on Vaiśākha,[170] but in China, the event is celebrated on the 8th day of the second month of the Chinese calendar, in the same month the Buddha's passing into final Nirvana is celebrated.[171]

In literature worldwide

[edit]Medieval

[edit]

A version of the life story of the Buddha was incorporated in the work of the Shi'ite Muslim theologian Ibn Bābūya (923–991). In this story, titled Balawhar wa-Būdāsf, the main character is horrified by his harem attendants and decides to leave his father's palace to seek spiritual fulfillment.[172] Balawhar wa-Būdāsf would later be widely circulated and modified into the story of the legendary Christian saints Barlaam and Josaphat, being passed down through the Manichaeans, the Islamic world and the Christian East.[173] From the 11th century onward, this story would in turn become very popular and would significantly affect western spiritual life. Its romantic and colorful setting, as well as the powerful structure of the story caused it to enjoy "a popularity attained perhaps by no other legend".[174] The story would be translated in many languages, including the 13th-century Islandic Barlaam's Saga.[175] In total, over sixty versions of the story were written in the main languages of Europe, the Christian East and Christian Africa, reaching nearly every country in the Christian world.[174]

"And how can this world avoid being full of sorrow and complaint? There is nobody on earth who can rejoice in his children or his treasures without constantly worrying about them as well. Sorrow and heartache are brought on by the anticipation of impending evils, the onset of sickness or accidental injuries, or else the coming of death itself upon a man's head. The sweetness of self-indulgence turns into bitterness. Delights are rapidly succeeded by depression, from which there is no escape."

—The Balavariani (Barlaam and Josaphat), Lang (1966, p. 57), cited in Almond (1987, p. 399)

The Christian story of Barlaam and Josaphat starts out very similar to the story of Prince Siddhārtha, but the birth of the prince is preceded by a discussion between his father, the Indian king Abenner, and a nobleman turned Christian ascetic. In this conversation, the ascetic points at the limitations of the worldly life, in which no real satisfaction can be found. After the birth of the prince Josaphat, the double prediction of his possible future, his growing up in a protected environment, and the first three of the four sights, he enters upon a personal crisis. Then he meets with the Ceylonese sage Barlaam, who introduces him to the Christian faith. The king attempts at first to fool his young son in understanding that Barlaam has lost a debate with people in the court, but to no avail. Next, he sends women to tempt the prince, but again, unsuccessfully: Josaphat wishes to renounce the worldly life and become an ascetic. The king manages to persuade his son to stay, however, by giving him half of his kingdom. Accepting the offer, King Josaphat becomes a good king and his Christian kingdom prospers more than that of his father, who eventually converts. After the death of his father, however, Josaphat gives up the throne to become an ascetic as he originally intended, and spends the final years of his life with Barlaam in Ceylon.[176]

It would take up until 1859 before well-known Western translators and scholars realized that the story was derived from the life of the Buddha, although the similarities had been noticed before by a less well-known Venetian editor and Portuguese traveler in the 15th and 16th centuries, respectively.[177] Although the story has been passed on through different languages and countries, some basic tenets of Buddhism can still be found in it: the nature of duḥkha in life as expressed in the opening dialogue between the nobleman and the king; the cause of suffering being desire; the path of self-analysis and self-control which follows this realization, and there are even some hints that point at ideals similar to the Buddhist Nirvana.[178]

Modern

[edit]

The legend of Barlaam and Josaphat affected Western literature up until early modern times: Shakespeare used the fable of the caskets for his The Merchant of Venice, probably basing the fable on an English translation of a late medieval version of the story.[174] In the 19th century, the Great Renunciation was a major theme in the biographical poem The Light of Asia by the British poet Edwin Arnold (1832–1904), to the extent that it became the subtitle of the work.[179] The work was based on the Chinese translation of the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra.[180] The focus on the renunciation in the life of the Buddha contributed to the popularity of the work, as well as the fact that Arnold left out many miraculous details of the traditional accounts to increase its appeal to a post-Darwinian audience.[181] Moreover, Arnold's depiction of Prince Siddhārtha as an active and compassionate truth-seeker defying his father's will and leaving the palace life went against the stereotype of the weak-willed and fatalistic Oriental, but did conform with the middle-class values of the time. Arnold also gave a much more prominent role to Yaśodharā than traditional sources, having Prince Siddhārtha explain his departure to his wife extensively, and even respectfully circumambulating her before leaving. The Light of Asia therefore inclined both "... toward imperial appropriation and toward self-effacing acknowledgment of the other".[182] Arnold's depiction of the Buddha's renunciation inspired other authors in their writings, including the American author Theodore Dreiser (1871–1945)[183] and Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986).[184]

Borges was greatly influenced by the story of the renunciation of the Buddha, and wrote several essays and a book about it. The emphasis on plot above character, and the aspects of epiphany and destiny appealed to him, as well as the adaptable and archetypical nature of the story. Borges used the story of the Buddha's renunciation, mixed with ideas of Schopenhauer (1788–1860) and idealism, to formulate his universal model of narrative. Borges based his works on The Light of Asia, as well as numerous translations of traditional Buddhist texts.[185]

Borges saw in the Great Renunciation the anti-thesis for the realist novel: a story in which mythological motif is more important than psychology of character, and authorial anonymity is a key factor. Furthermore, he saw in the story the proof of the universal and archetypical nature of literature, deriving from Goethe's idea of morphology. This biological theory presumed an archetypical, intuitive unity behind all living forms: Borges presumed a similar idea in literature, in which from only a small number of archetypes all literary forms and narratives could be derived. To prove his point, he connected the Great Renunciation of the Buddha with Arabian, Chinese and Irish stories, and explained that the same motifs were at play: for example, the motif of the ascetic who shows the meaninglessness of the king's land, and thereby destroys the king's confidence.[186] Comparative literature scholar Dominique Jullien concludes that the story of the Great Renunciation, the widespread narrative of the king and the ascetic, is a confrontation between a powerful and powerless figure. However, the powerless figure has the last word, leading to change and reform in the king.[187]

Not only the original story of Prince Siddhārtha influenced modern writers. The derived story of Barlaam and Josaphat has much influenced the Russian writer Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910). Indeed, he went through a renunciation himself in the middle of his life, inspired by the story.[174]

In popular culture

[edit]A more recent interpretation is the 2011 anime Buddha: The Great Departure (Japanese: 手塚治虫のブッダ赤い砂漠よ!美しく, romanized: Buddha 2: Tezuka Osamu no Buddha) by film maker Yasuomi Ishitō. This is the first installment of a trilogy of animes based on the first three volumes out of Osamu Tezuka's 14-volume manga series Buddha. The movie covers familiar elements such as the protected upbringing and the prince's disillusionment with the world, as it deals with the first fifteen years of the prince's life.[188] Prince Siddhārta is depicted as a sensitive person, who is motivated to renounce his life in the palace because of the horrors of war. The movie also addresses the philosophical themes that Prince Siddhārtha struggles with, that is, the suffering of old age, sickness and death and how to transcend this.[189]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although Buddhist studies scholar Hubert Durt preferred 'Sūtra on the Collected Original Activities of the Buddha'.[10]

- ^ In some versions, 60 Brahmins study the dreams,[17] and 108 Brahmins are invited to name the child.[18] Also, the response of Asita to the child sometimes precedes and spurs the decision to invite the Brahmins.[19]

- ^ In some versions, however, the meditation at the Jambu tree is placed much later in the story.[27][28]

- ^ Most textual traditions agree that the prince was 29 years old during his renunciation. Some Chinese translations mention 19 years, however.[34]

- ^ According to some traditional sources, Prince Siddhārtha was still sixteen then.[42] But some sources say that Rāhula was born seven days before the prince left the palace.[43][25]

- ^ Other texts derive rāhu differently. For example, the Pāli Apadāna, as well as another account found in the texts of monastic discipline of the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition, derive rāhu from the eclipse of the moon, which traditionally was seen to be caused by the asura (demon) Rāhu.[48] The Apadāna states that just like the moon is obstructed from view by Rāhu, Prince Siddhārtha was obstructed by Rāhula's birth.[48][49] Further credence is given to the astrological theory of Rāhula's name by the observation that sons of previous Buddhas were given similar names, related to constellations.[47]

- ^ Kisā was called Mṛgajā in the Mulasarvāstivāda version of the story, and Mṛgī in the Mahāvastu version.[51] In some accounts, she became the prince's wife just before he left.[52] This Kisā is not to be confused with the Kisā Gotami who would later become a disciple after the prince had become the Buddha.

- ^ Some textual traditions, such as those of the Mahīśāsaka and the Dharmaguptaka, mention no attendant escorting the prince.[72]

- ^ Foucher has even suggested that the depiction of the four sights might have affected ancient art in other parts of the world, raising the example of frescoes from the Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa. These frescoes show young men discovering corpses in coffins.[151]

- ^ But already in the 1930s, this custom was being replaced by riding in a car or cart.[166]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "The Great Departure or Mahābhiniṣkramaṇa". 24 October 2022.

- ^ Sattar, Noor (May 2022). "Feminine Participation in the Donors World: A Glimpse from the Inscribed Records of the Pāla - Sena Period". The Maha Bodhi The International Buddhist Journal.

- ^ Albery 2017, p. 360.

- ^ See Bechert (2004, p. 85), Deeg (2010, pp. 51–52) and Sarao (2017, Biography of the Buddha and Early Buddhism). Sarao mentions the early discourses; Deeg mentions the monastic discipline.

- ^ a b Luczanits 2010, p. 50, note 48.

- ^ a b Bechert 2004, p. 85.

- ^ a b Deeg 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Tanabe 2018, p. 427.

- ^ Harvey 2013.

- ^ a b Durt 2004, p. 56.

- ^ See Crosby (2014, pp. 29–31) and Strong (2015, Past Buddhas and the Biographical Blueprint, table 2.2.). Strong mentions the scope.

- ^ Crosby 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Deeg 2010, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Tanabe 2018, p. 426.

- ^ Strong 2001, Lifestories and Buddhology: The Development of a Buddha-Life Blueprint.

- ^ See Malalasekera (1960, Vol. 1, Gotama), Bridgwater (2000) and Sarao (2017, p. 186). Sarao mentions the auspicious characteristics and Malalasekera mentions the eight Brahmins. For the natural mother's dreams and Asita, see Smart (1997, p. 276). For the father's dreams, see Mayer (2004, p. 238).

- ^ Penner 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Irons 2008, p. 280, Kaundinya.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 393.

- ^ See Lopez, D.S. (12 July 2019). "Buddha – Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 July 2019 and Strong (2015, Birth and Childhood). Strong mentions Asita's single prediction.

- ^ Tyle 2003.

- ^ a b Malalasekera 1960, Vol. 1, Gotama.

- ^ Bechert 2004, pp. 83, 85.

- ^ See Lopez, D.S. (12 July 2019). "Buddha – Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 July 2019 and Penner (2009, p. 24). For the attendants, see Penner.

- ^ a b c d e f Sarao 2017, Biography of the Buddha and Early Buddhism.

- ^ a b Strong 2015, The Beginnings of Discontent.

- ^ Thomas 1951, p. 136.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Smart 1997, p. 276.

- ^ Penner 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Strong 2015.

- ^ a b Strong 2001, Upbringing in the Palace.

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Albery 2017, pp. 370–371, note 28.

- ^ See Penner (2009, pp. 24–27) and Hiltebeitel (2011, p. 632). Hiltebeitel mentions that the fourth sign was not brought about by deities, though Lopez & McCracken (2014, p. 24) refer to accounts that do describe the ascetic as a disguised deity.

- ^ Lopez & McCracken 2014, p. 21.

- ^ Penner 2009, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Warder 2000, p. 322.

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 243.

- ^ For the hope and the relation with duḥkha, see Strong (2015, The Beginnings of Discontent). For the non-violence, see Warder (2000, p. 322).

- ^ Penner 2009, pp. 26.

- ^ Keown 2004, p. 267.

- ^ Malalasekera 1960, Rāhulamātā.

- ^ Powers 2013, Rāhula.

- ^ a b Saddhasena 2003, p. 481.

- ^ Irons 2008, p. 400, Rahula.

- ^ a b Rahula 1978, p. 136.

- ^ a b Malalasekera 1960, Rāhula.

- ^ Crosby 2013, p. 105.

- ^ Thomas 1931, p. 53.

- ^ Strong 2001, p. 206.

- ^ Thomas 1931, p. 54 note 1.

- ^ Collins (1998, p. 393). For the double translation, see Strong (2001, Incitements to Leave Home). For the Sanskrit rendering of the word in the song, see Hiltebeitel (2011, p. 644).

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 73.

- ^ Foucher 2003, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Powers 2016, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Strong 2001, The Great Departure.

- ^ a b c Strong 2001, Incitements to Leave Home.

- ^ a b c Strong 2015, The Great Departure.

- ^ Rahula 1978, p. 242.

- ^ See Schober (2004, p. 45) and Strong (2001, Incitements to Leave Home). Strong mentions the nature of the body.

- ^ Beal 1875, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Jones 1952, p. 131.

- ^ Reynolds & Hallisey (1987) mention that it was against his father's will. Smart (1997, p. 276) mentions the time.

- ^ Bridgwater 2000.

- ^ Penner 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Collins 1998, p. 394.

- ^ Ohnuma 2016, Kanthaka in the Great Departure.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Skilling 2008, pp. 106–107.

- ^ See Strong (2001, The Great Departure). For the city goddess, see Foucher (2003, p. 77).

- ^ Pons 2014, p. 29.

- ^ Strong (2001, The Great Renunciation). For the three kingdoms, see Thomas (1951, p. 137).

- ^ Penner 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Penner 2009, p. 154.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d Ohnuma 2016.

- ^ Keown 2004, p. 137, Kanthaka.

- ^ Ohnuma 2016, Kanthaka as the Buddha's Scapegoat.

- ^ See Powers (2016, p. 15) and Strong (2015, The Great Departure). For Malla, see Schumann (1982, p. 45). For Indra, see Rahula (1978, p. 246).

- ^ Filigenzi 2005, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Hirakawa 1990, p. 24.

- ^ See Strong (2001, The Great Departure) and Strong (2015, The Great Departure). The 2001 work mentions the promise. For the retainer and the position, see Hirakawa (1990, p. 25).

- ^ Foucher 2003, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Albery 2017, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Albery 2017, pp. 370–371 note 28.

- ^ See Buswell & Lopez (2013, Rāhula) and Strong (2001, The Great Renunciation). For the Mahāvastu, see Lopez & McCracken (2014, p. 31).

- ^ Meeks 2016, pp. 139–40.

- ^ Sasson & Law 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Strong 1997, p. 119.

- ^ Weber 1958, p. 204.

- ^ a b Maxwell 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Strong 2001, The Making of a Monk.

- ^ Baroni 2002, p. 118, The Great Renunciation.

- ^ For the "good", see Smart (1997) and Hirakawa (1990, p. 24). For the state beyond death, see Blum (2004, p. 203).

- ^ a b c Harvey 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Strong 2015, The Middle Way.

- ^ Brekke 2005, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Analayo 2017, The Motivation to Go Forth.

- ^ Schumann 1982, p. 44.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Armstrong 2001, Ch.1.

- ^ Brekke 1999, p. 857.

- ^ Gwynne 2018, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jestice 2004, p. 193, Compassion and Holy People.

- ^ Shaw 2013, p. 460.

- ^ Jones 1949, p. 189.

- ^ Shaw 2013, pp. 460–461.

- ^ Woodward 1997, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Strong 2015, Past Buddhas and the Biographical Blueprint.

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 267.

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 15.

- ^ a b Smart 1997, p. 277.

- ^ a b Sarao 2019.

- ^ See Gombrich (2006, p. 50). For the alternation, see Hirakawa (1990, p. 21). For the fact that Śuddhodana was the current rāja, see Schumann (1982, p. 6).

- ^ For being a landowner and noble, see Foucher (2003, pp. 52–53). For the quote, see Schumann (1982, p. 18).

- ^ See Warder (2000, p. 45) and Foucher (2003, p. 64). For the quote, see Warder. Foucher explains that three palaces, each for a different season, were not uncommon for the rich at that time, because the weather in the three seasons was so extremely different.

- ^ Wynne (2015, p. 14). For the multiple levels, see Schumann (1982, p. 21).

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 213.

- ^ Schumann 1982, pp. 14–17.

- ^ a b Bechert 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Harvey 2013, p. 14.

- ^ a b Strong 2015, The Buddha's World.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 80, note transl..

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 60.

- ^ See Bechert (2004, p. 85) and Strong (2015, Past Buddhas and the Biographical Blueprint). Strong mentions the name of the text and the name of the Buddha.

- ^ Reynolds 1976, p. 43.

- ^ For the overcoming of delusion, see Schumann (1982, p. 22) and Analayo (2017, The Motivation to Go Forth). For the conquering, see Eliade (1982, p. 74).

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 263.

- ^ See Wynne (2015, p. 14) and Analayo (2017, The Motivation to Go Forth). For the quote, see Wynne. For the role of old age, etc., see Analayo.

- ^ Bareau 1974, pp. 238 note 1, 241, 245 note 1, 246, 264.

- ^ Weller 1928, p. 169.

- ^ Schumann 1982, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Wynne 2015, p. 15.

- ^ See Schumann (1982, p. 46), Eliade (1982, p. 74) and Foucher (2003, p. 72).

- ^ Eliade 1982, p. 74.

- ^ Schumann 1982, p. 46.

- ^ Schumann 1982, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 249.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 69.

- ^ Crosby 2013, pp. 108–9.

- ^ See Strong (2001, The Great Departure). For the Mahāvastu, see Lopez & McCracken (2014, pp. 31–32).

- ^ Strong 2001, Further Conversions in Benares: Yasa and his Family.

- ^ Bareau 1974, p. 253.

- ^ Hiltebeitel 2011, pp. 639–641, 643.

- ^ Brekke 1999, pp. 857–859, 861.

- ^ Strong 2015, Birth and Childhood.

- ^ Silk 2003, pp. 869–870, 872–873.

- ^ Thomas 1931, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Norman 1992, pp. 231–232.

- ^ Foucher 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Crosby 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Maxwell 2004.

- ^ Tanabe 2018, pp. 423.

- ^ Arlt & Hiyama 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Hudson, Gutman & Maung 2018, p. 14.

- ^ Pons 2014, p. 17.

- ^ a b Albery 2017, pp. 358–359.

- ^ For the goddess, see Mevissen (2011, p. 96). For the veiled woman, see Filigenzi (2005, p. 105 note 3).

- ^ Pons 2014, p. 41.

- ^ Schober 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Strong 2001, Lifestory and Ritual.

- ^ See Strong (2005, p. 5690) and Strong (2001, Lifestory and Ritual). The 2001 work mentions the relatives and deities.

- ^ Terwiel 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Swearer 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Wells 1939, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Wells 1939, p. 140, note 1.

- ^ Strong 2001, Lifestory and Ritual; Incitements to Leave Home.

- ^ Schober 1997, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Keown 2004, p. 335, Wesak.

- ^ Barber 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Crosby 2014, p. 101.

- ^ For the influence of Bābūya's version, see Crosby (2014, p. 101) and Mershman (1907). For the way through which the story was passed down, see Almond (1987, p. 406).

- ^ a b c d Almond 1987, p. 391.

- ^ Jullien 2019, p. 5.

- ^ Almond 1987, pp. 392–393, 397.

- ^ Almond 1987, pp. 395–396.

- ^ Almond 1987, pp. 395–396, 398–400.

- ^ Jullien 2019, p. xix.

- ^ Stenerson 1991, p. 392.

- ^ See Jullien (2019, p. xix). For the miracles, see Franklin (2008, p. 32).

- ^ Franklin 2008, pp. 40, 42–43, 46, 48–49, quote is on page 49.

- ^ Stenerson 1991, p. 396 ff..

- ^ Jullien 2019, passim.

- ^ Jullien 2019, pp. xiii–xiv, xi–xii, xix.

- ^ Jullien 2019, pp. xxi, 2, 6–7, 14–15.

- ^ Jullien 2019, pp. 99–100.

- ^ For the disillusionment and the fifteen years, see Cabrera, David (12 July 2011). "Buddha: The Great Departure". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 13 May 2019. For the three volumes, see Gray, Richard (14 December 2011). "JFF15 Review: Buddha – The Great Departure". The Reel Bits. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019.

- ^ v.d. Ven, Frank. "Osamu Tezukas Buddha - The Great Departure - Tezuka Osamu no Buddha - Akai sabakuyo utsukushiku (2011) recensie" [review]. Cinemagazine (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 14 April 2015.

References

[edit]- Almond, P. (1987), "The Buddha of Christendom: A Review of The Legend of Barlaam and Josaphat", Religious Studies, 23 (3): 391–406, doi:10.1017/S0034412500018941

- Analayo, Bhikkhu (2017), A Meditator's Life of the Buddha: Based on the Early Discourses, Windhorse Publications, ISBN 978-1-911407-00-3

- Albery, Henry (2017), "Astro-biographies of Śākyamuni and the Great Renunciation in Gandhāran Art", in Sheel, Kamal; Willemen, Charles; Zysk, Kenneth (eds.), From Local to Global: Papers in Asian History and Culture. Prof. AK Narain Commemoration Volume, vol. 2, Buddhist World Press, pp. 346–382, ISBN 9789380852744, archived from the original on 24 October 2019

- Arlt, R.; Hiyama, S. (2016), "New Evidence for the Identification of the Figure with a Bow in Depictions of the Buddha's Life in Gandharan Art", Distant Worlds Journal, 1: 187–205

- Armstrong, Karen (2001), Buddha, Paw Prints, ISBN 978-1-4395-6868-2

- Barber, A.W. (2005), "Buddhist Calendar", in Davis, E.L. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture, Routledge, pp. 67–68, ISBN 0-203-64506-5

- Bareau, A. (1974), "La jeunesse du Buddha dans les Sûtrapitaka et les Vinayapitaka anciens" [The Buddha's Youth in the Sūtrapiṭaka and the Ancient Vinayapiṭaka] (PDF), Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (in French), 61 (1): 199–274, doi:10.3406/befeo.1974.5196[permanent dead link]

- Baroni, Helen J. (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism, Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6

- Bechert, Heinz (2004), "Buddha, Life of the", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Thomson Gale, pp. 82–88, ISBN 0-02-865720-9

- Beal, Samuel (1875), The Romantic Legend of Sâkya Buddha (PDF), Trübner & Co., OCLC 556560794

- Blum, M.L. (2004), "Death", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Thomson Gale, pp. 203–210, ISBN 0-02-865720-9

- Brekke, T. (1999), "The Religious Motivation of the Early Buddhists", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 67 (4): 849–866, doi:10.1093/jaarel/67.4.849

- Brekke, T. (2005), Religious Motivation and the Origins of Buddhism: A Social-Psychological Exploration of the Origins of a World Religion, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-78849-0

- Bridgwater, William (2000), "Buddha", The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.), Columbia University Press, archived from the original on 21 April 2019

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3

- Collins, S. (1998), Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57054-1

- Crosby, Kate (2013), "The Inheritance of Rāhula: Abandoned Child, Boy Monk, Ideal Son and Trainee", in Sasson, Vanessa R. (ed.), Little Buddhas: Children and Childhoods in Buddhist Texts and Traditions, Oxford University Press, pp. 97–123, ISBN 978-0-19-994561-0

- Crosby, Kate (2014), Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity, Wiley Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-8906-4

- Deeg, M. (2010), "Chips from a Biographical Workshop—Early Chinese Biographies of the Buddha: The Late Birth of Rāhula and Yaśodharā's Extended Pregnancy", in Covill, L.; Roesler, U.; Shaw, S. (eds.), Lives Lived, Lives Imagined: Biography in the Buddhist Traditions, Wisdom Publications and Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, pp. 49––88, ISBN 978-0-86171-578-7

- Durt, Hubert (2004), "On the Pregnancy Of Maya II: Late Episodes", Journal of the International College for Advanced Buddhist Studies, 7: 216–199, ISSN 1343-4128

- Eliade, Mircea (1982), Histoire des croyances et des idees religieuses. Vol. 2: De Gautama Bouddha au triomphe du christianisme [A history of religious ideas: From Gautama Buddha to the Triumph of Christianity] (in French), University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-20403-0

- Filigenzi, Anna (2005), "Gestures and Things: The Buddha's Robe in Gandharan Art", East and West, 55 (1/4), Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente: 103–116, ISSN 0012-8376, JSTOR 29757639

- Foucher, A. (2003) [1949], La vie du Bouddha, d'après les textes et les monuments de l'Inde [The Life of the Buddha: According to the Ancient Texts and Monuments of India] (in French) (1st Indian ed.), Munshiram Manoharlal, ISBN 81-215-1069-4

- Franklin, J.J. (2008), The Lotus and the Lion: Buddhism and the British Empire, Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-4730-3

- Gombrich, Richard (2006), Theravāda Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-01603-9

- Gwynne, Paul (2018), World Religions in Practice: a Comparative Introduction (2nd ed.), John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-118-97228-1

- Harvey, Peter (2013), An Introduction to Buddhism: Teachings, History And Practices (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85942-4

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2011), Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-539423-8

- Hirakawa, Akira (1990), A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1203-4

- Hudson, B.; Gutman, P.; Maung, W. (2018), "Buddha's Life in Konbaung Period Bronzes from Yazagyo", Journal of Burma Studies, 22 (1): 1–30, doi:10.1353/jbs.2018.0000, ISSN 2010-314X

- Irons, Edward (2008), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Facts on File, ISBN 978-0-8160-5459-6

- Jestice, P.G., ed. (2004), Holy People of the World: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-85109-649-3

- Jones, J.J. (1949), The Mahāvastu, vol. 1, Pali Text Society, OCLC 221926551

- Jones, J.J. (1952), The Mahāvastu, vol. 2, Pali Text Society, OCLC 468282520

- Jullien, Dominique (2019), Borges, Buddhism and World Literature: A Morphology of Renunciation Tales, Literatures of the Americas, Palgrave Macmillan, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04717-7, ISBN 978-3-030-04717-7

- Keown, Damien (2004), A Dictionary of Buddhism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2

- Lang, D.M. (1966), The Balavariani (Barlaam and Josaphat): A Tale from the Christian East Translated from the Old Georgian, original by John of Damascus (c. 675 – 749), Allen & Unwin, OCLC 994799791

- Lopez, Donald S.; McCracken, Peggy (2014), In Search of the Christian Buddha: How an Asian Sage Became a Medieval Saint, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-08915-8

- Luczanits, Christian (2010), "Prior to Birth. The Tuṣita episodes in Indian Buddhist Literature and Art" (PDF), in Cüppers, C.; Deeg, M.; Durt, Hubert (eds.), The Birth of the Buddha. Proceedings of the Seminar Held in Lumbini, Nepal, October 2004, Lumbini International Research Institute, pp. 41–91, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2019

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, Pali Text Society, OCLC 793535195

- Maxwell, Gail (2004), "Buddha, Life Of The, In Art", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Thomson Gale, pp. 88–92, ISBN 0-02-865720-9, archived from the original on 15 July 2019

- Mayer, A.L. (2004), "Dreams", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Thomson Gale, pp. 238–239, ISBN 0-02-865720-9

- Meeks, Lori (27 June 2016), "Imagining Rāhula in Medieval Japan", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 43 (1): 131–51, doi:10.18874/jjrs.43.1.2016.131-151

- Mershman, Francis (1907). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Mevissen, G.J.R. (2011), "The Great Renunciation: Astral Deities in Gandhāra", Pakistan Heritage, 3: 89–112, ISSN 2073-641X

- Norman, K.R. (1992), "A Note on Silāvigaḍabhīcā in Aśoka's Rummindei Inscription", in Skorupski, Tadeusz; Pagel, Ulrich (eds.), The Buddhist Forum, vol. iii, Institute of Buddhist Studies, Tring and Institute Of Buddhist Studies, Berkeley, pp. 227–238, ISBN 0-7286-0231-8

- Ohnuma, Reiko (2016), "Animal Doubles of the Buddha", Humanimalia, 7 (2): 1–34, doi:10.52537/humanimalia.9664, ISSN 2151-8645, archived from the original on 10 August 2019

- Penner, Hans H. (2009), Rediscovering the Buddha: The Legends and Their Interpretations, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538582-3

- Pons, J. (2014), "The Figure with a Bow in Gandhāran Great Departure Scenes. Some New Readings", Entangled Religions, 1: 15–94, doi:10.46586/er.v1.2014.15-94, archived from the original on 27 August 2019

- Powers, John (2013), A Concise Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1-78074-476-6

- Powers, John (2016), "Buddhas and Buddhisms", in Powers, John (ed.), The Buddhist World, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-315-68811-4

- Rahula, T. (1978), A Critical Study of the Mahāvastu, Motilal Banarsidass, OCLC 5680748

- Reynolds, F.E. (1976), "The Many Lives of Buddha: A Study of Sacred Biography and Theravāda Tradition", in Reynolds, F.E.; Capps, D. (eds.), The Biographical Process: Studies in the History and Psychology of Religion, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 9789027975225

- Reynolds, F.E.; Hallisey, C. (1987), "Buddha", Encyclopedia of Religion, Thomson Gale

- Saddhasena, D. (2003), "Rāhula", in Malalasekera, G. P.; Weeraratne, W. G. (eds.), Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, vol. 7, Government of Sri Lanka, OCLC 2863845613[permanent dead link]

- Sarao, K. T. S. (2017), "History, Indian Buddhism", in Sarao, K. T. S.; Long, Jeffery D. (eds.), Buddhism and Jainism, Springer Nature, ISBN 9789402408515, archived from the original on 24 October 2019

- Sarao, K.T.S. (2019), "Kapilavatthu", in Sharma, A. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Springer Netherlands, ISBN 9789400719880, archived from the original on 24 October 2019

- Sasson, Vanessa R.; Law, Jane Marie (2008), Imagining the Fetus: The Unborn in Myth, Religion, and Culture, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-970174-2

- Schober, J. (1997), "In the Presence of the Buddha: Ritual Veneration of the Burmese Mahāmuni Image", in Schober, J. (ed.), Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia, University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 259–288, ISBN 978-0-8248-1699-5

- Schober, J. (2004), "Biography", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Thomson Gale, pp. 45–47, ISBN 0-02-865720-9

- Schumann, H.W. (1982), Der Historische Buddha [The Historical Buddha: The Times, Life, and Teachings of the Founder of Buddhism] (in German), translated by Walshe, M. O' C., Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1817-0

- Shaw, Sarah (2013), "Character, Disposition, and the Qualities of the Arahats as a Means of Communicating Buddhist Philosophy in the Suttas", in Emmanuel, Steven M. (ed.), A Companion to Buddhist Philosophy, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-470-65877-2

- Silk, J.A. (2003), "The Fruits of Paradox: On the Religious Architecture of the Buddha's Life Story", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 71 (4): 863–881, doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfg102, hdl:1887/3447560, archived from the original on 9 October 2019

- Skilling, Peter (2008), "New discoveries from South India: The life of the Buddha at Phanigiri, Andhra Pradesh", Arts Asiatiques, 63 (1): 96–118, doi:10.3406/arasi.2008.1664

- Smart, N. (1997), "Buddha", in Carr, B.; Mahalingam, I. (eds.), Companion Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy (1st ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-203-01350-6

- Stenerson, D.C. (1991), "Some Impressions of the Buddha: Dreiser and Sir Edwin Arnold's the Light of Asia", Canadian Review of American Studies, 22 (3): 387–406, doi:10.3138/CRAS-022-03-05

- Strong, John S. (1997), "A Family Quest: The Buddha, Yaśodharā, and Rāhula in the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya", in Schober, Juliane (ed.), Sacred Biography in the Buddhist Traditions of South and Southeast Asia, pp. 113–28, ISBN 978-0-8248-1699-5

- Strong, J.S. (2001), The Buddha: A Beginner's Guide, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1-78074-054-6

- Strong, J.S. (2005), "Māra", in Jones, Lindsay (ed.), Encyclopedia of religion, vol. 8 (2nd ed.), Thomson Gale, ISBN 0-02-865741-1

- Strong, J.S. (2015), Buddhisms: An Introduction, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1-78074-506-0

- Swearer, D. (2010), The Buddhist World of Southeast Asia (2nd ed.), State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1-4384-3251-9

- Tanabe, K. (March 2018), "Not Benzhi/Benshi (賁識, 奔識) but Vaisravana/Kuvera (毘沙門天): Critical Review of Arlt/Hiyama's Article on Gandharan Great Departure", Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for the Academic Year 2017, 21: 423–438, ISSN 1343-8980

- Terwiel, Barend (2012), Monks and Magic: Revisiting a Classic Study of Religious Ceremonies in Thailand (4th ed.), NIAS Press, ISBN 978-87-7694-066-9

- Thomas, E.J. (1931), The Life of Buddha as Legend and History (PDF) (2nd ed.), Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, OCLC 1893707

- Thomas, E.J. (1951), The History of Buddhist Thought (PDF) (2nd ed.), Routledge and Kegan Paul, OCLC 49690643

- Tyle, L.B. (2003), "Buddha", UXL Encyclopedia of World Biography, Thomson Gale

- Warder, A.K. (2000), Indian Buddhism (3rd ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0818-5

- Weber, M. (1958), The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism, Free Press, OCLC 874200316

- Weller, F. (1928), "Die Überlieferung des älteren buddhistischen Schrifttums" [The Passing on of Ancient Buddhist Texts] (PDF), Asia Major (in German), 5: 149–82, archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2019

- Wells, Kenneth E. (1939), Thai Buddhism: Its Rites and Activities, Bangkok Times Press, OCLC 1004812732

- Woodward, M.R. (1997), "The Biographical Imperative in Theravāda Buddhism", in Schober, J. (ed.), Sacred biography in the Buddhist traditions of South and Southeast Asia, University of Hawai'i Press, pp. 40–63, ISBN 978-0-8248-1699-5

- Wynne, Alexander (2015), Buddhism: An Introduction, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84885-397-3