Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Auguste Millière (1880) oil on canvas | |

| Born | Thomas Pain[1] January 29, 1737[Note 1] |

| Died | June 8, 1809 (aged 72) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| School | Enlightenment, liberalism, republicanism |

Main interests | Politics, ethics, religion |

| Signature | |

Thomas Paine (February 9, 1737 [O.S. January 29, 1736][Note 1][Note 2][Note 3] – June 8, 1809) was an English-American political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. One of the Founding Fathers of the United States, he authored the two most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution, and he inspired the rebels in 1776 to declare independence from Britain.[2] His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era rhetoric of transnational human rights.[3] He has been called "a corsetmaker by trade, a journalist by profession, and a propagandist by inclination".[4]

Born in Thetford, England, in the county of Norfolk, Paine emigrated to the British American colonies in 1774 with the help of Benjamin Franklin, arriving just in time to participate in the American Revolution. Virtually every rebel read (or listened to a reading of) his powerful pamphlet Common Sense (1776), proportionally the all-time best-selling[5][6] American title which crystallized the rebellious demand for independence from Great Britain. His The American Crisis (1776–83) was a prorevolutionary pamphlet series. Common Sense was so influential that John Adams said, "Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain."[7]

Paine lived in France for most of the 1790s, becoming deeply involved in the French Revolution. He wrote Rights of Man (1791), in part a defense of the French Revolution against its critics. His attacks on British writer Edmund Burke led to a trial and conviction in absentia in 1792 for the crime of seditious libel. In 1792, despite not being able to speak French, he was elected to the French National Convention. The Girondists regarded him as an ally. Consequently, the Montagnards, especially Robespierre, regarded him as an enemy.

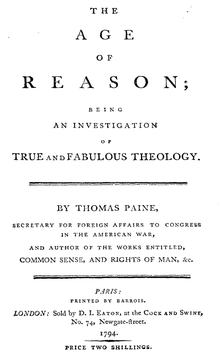

In December 1793, he was arrested and imprisoned in Paris, then released in 1794. He became notorious because of his pamphlets The Age of Reason (1793–94), in which he advocated deism, promoted reason and free thought, and argued against institutionalized religion in general and Christian doctrine in particular. He also published the pamphlet Agrarian Justice (1797), discussing the origins of property, and introduced the concept of a guaranteed minimum income. In 1802, he returned to the U.S. where he died on June 8, 1809. Only six people attended his funeral as he had been ostracized for his ridicule of Christianity.[8]

Early life and education

Paine was born on January 29, 1736[Note 1] (NS February 9, 1737), the son of Joseph Pain, or Paine, a Quaker, and Frances (née Cocke), an Anglican, in Thetford, an important market town and coach stage-post, in rural Norfolk, England.[9] Born Thomas Pain, despite claims that he changed his family name upon his emigration to America in 1774,[1] he was using Paine in 1769, while still in Lewes, Sussex.[10]

He attended Thetford Grammar School (1744–49), at a time when there was no compulsory education.[11] At the age of 13, he was apprenticed to his stay-maker father. Paine researchers contend his father's occupation has been widely misinterpreted to mean that he made the stays in ladies' corsets, which likely was an insult later invented by his political foes.[citation needed] Actually, the father and apprentice son made the thick rope stays (also called stay ropes) used on sailing ships.[12][better source needed] Thetford historically had maintained a brisk trade with the downriver, then major, port town of King's Lynn.[13][failed verification]

A connection to shipping and the sea explains why, in late adolescence, Thomas enlisted and briefly served as a privateer,[14][15][better source needed] before returning to Britain in 1759. There, he became a master stay-maker, establishing a shop in Sandwich, Kent.[16] On September 27, 1759, Thomas Paine married Mary Lambert. His business collapsed soon after. Mary became pregnant; and, after they moved to Margate, she went into early labor, in which she and their child died.

In July 1761, Paine returned to Thetford to work as a supernumerary officer. In December 1762, he became an Excise Officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire; in August 1764, he was transferred to Alford, also in Lincolnshire, at a salary of £50 per annum. On August 27, 1765, he was dismissed as an Excise Officer for "claiming to have inspected goods he did not inspect". On July 31, 1766, he requested his reinstatement from the Board of Excise, which they granted the next day, upon vacancy. While awaiting that, he worked as a stay-maker. Again, he was making stay ropes for shipping, not stays for corsets.[17]

In 1767, he was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall; subsequently, he asked to leave this post to await a vacancy, thus, he became a schoolteacher in London.

On February 19, 1768, he was appointed to Lewes in Sussex, a town with a tradition of opposition to the monarchy and pro-republican sentiments going back to the revolutionary decades of the 17th century.[18] Here he lived above the fifteenth-century Bull House, the tobacco shop of Samuel Ollive and Esther Ollive.

There, Paine first became involved in civic matters, and he appears in the Town Book as a member of the Court Leet, the governing body for the town. He was also a member of the parish vestry, an influential local church group whose responsibilities for parish business would include collecting taxes and tithes to distribute among the poor. On March 26, 1771, at the age of 34, he married Elizabeth Ollive, his landlord's daughter.

From 1772 to 1773, Paine joined excise officers asking Parliament for better pay and working conditions, publishing, in summer of 1772, The Case of the Officers of Excise, a twenty-one-page article, and his first political work, spending the London winter distributing the 4,000 copies printed to the Parliament and others. In spring of 1774, he was again dismissed from the excise service for being absent from his post without permission; his tobacco shop failed, too. On April 14, to avoid debtors' prison, he sold his household possessions to pay debts. On June 4, 1774, he formally separated from his wife Elizabeth and moved to London, where, in September, mathematician, Fellow of the Royal Society, and Commissioner of the Excise George Lewis Scott introduced him to Benjamin Franklin,[19] who suggested emigration to British colonial America, and gave him a letter of recommendation. In October, Thomas Paine emigrated from Great Britain to the American colonies, arriving in Philadelphia on November 30, 1774.

He barely survived the transatlantic voyage. The ship's water supplies were bad, and typhoid fever killed five passengers. On arriving at Philadelphia, he was too sick to debark. Benjamin Franklin's physician, there to welcome Paine to America, had him carried off ship; Paine took six weeks to recover his health. He became a citizen of Pennsylvania "by taking the oath of allegiance at a very early period".[20] In January 1775, he became editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine, a position he conducted with considerable ability.

Paine designed the Sunderland Bridge of 1796 over the Wear River at Wearmouth, England. It was patterned after the model he had made for the Schuylkill River Bridge at Philadelphia in 1787, and the Sunderland arch became the prototype for many subsequent voussoir arches made in iron and steel.[21][22] He also received a British patent for a single-span iron bridge, developed a smokeless candle,[23] and worked with inventor John Fitch in developing steam engines.

American Revolution

Common Sense (1776)

Thomas Paine has a claim to the title The Father of the American Revolution[24][25] It rests on his pamphlets, especially Common Sense, which crystallized sentiment for independence in 1776. It was published in Philadelphia on January 10, 1776 and signed anonymously "by an Englishman." It became an immediate success, quickly spreading 100,000 copies in three months to the two million residents of the 13 colonies. In all about 500,000 copies total including unauthorized editions were sold during the course of the Revolution.[5][26] Paine's original title for the pamphlet was Plain Truth; Paine's friend, pro-independence advocate Benjamin Rush, suggested Common Sense instead.

The pamphlet came into circulation in January 1776, after the Revolution had started. It was passed around, and often read aloud in taverns, contributing significantly to spreading the idea of republicanism, bolstering enthusiasm for separation from Britain, and encouraging recruitment for the Continental Army. Paine provided a new and convincing argument for independence by advocating a complete break with history. Common Sense is oriented to the future in a way that compels the reader to make an immediate choice. It offers a solution for Americans disgusted with and alarmed at the threat of tyranny.[27]

Paine's attack on monarchy in Common Sense is essentially an attack on George III. Whereas colonial resentments were originally directed primarily against the king's ministers and Parliament, Paine laid the responsibility firmly at the king's door. Common Sense was the most widely read pamphlet of the American Revolution. It was a clarion call for unity against the corrupt British court, so as to realize America's providential role in providing an asylum for liberty. Written in a direct and lively style, it denounced the decaying despotisms of Europe and pilloried hereditary monarchy as an absurdity. At a time when many still hoped for reconciliation with Britain, Common Sense demonstrated to many the inevitability of separation.[28]

Paine was not, on the whole, expressing original ideas in Common Sense, but rather employing rhetoric as a means to arouse resentment of the Crown. To achieve these ends, he pioneered a style of political writing suited to the democratic society he envisioned, with Common Sense serving as a primary example. Part of Paine's work was to render complex ideas intelligible to average readers of the day, with clear, concise writing unlike the formal, learned style favored by many of Paine's contemporaries.[29] Scholars have put forward various explanations to account for its success, including the historic moment, Paine's easy-to-understand style, his democratic ethos, and his use of psychology and ideology.[30]

Common Sense was immensely popular in disseminating to a very wide audience ideas that were already in common use among the elite who comprised Congress and the leadership cadre of the emerging nation, who rarely cited Paine's arguments in their public calls for independence.[31] The pamphlet probably had little direct influence on the Continental Congress' decision to issue a Declaration of Independence, since that body was more concerned with how declaring independence would affect the war effort.[32] Paine's great contribution was in initiating a public debate about independence which had previously been rather muted.

One distinctive idea in Common Sense is Paine's beliefs regarding the peaceful nature of republics; his views were an early and strong conception of what scholars would come to call the democratic peace theory.[33]

Loyalists vigorously attacked Common Sense; one attack, titled Plain Truth (1776), by Marylander James Chalmers, said Paine was a political quack[34] and warned that without monarchy, the government would "degenerate into democracy".[35] Even some American revolutionaries objected to Common Sense; late in life John Adams called it a "crapulous mass". Adams disagreed with the type of radical democracy promoted by Paine (that men who did not own property should still be allowed to vote and hold public office), and published Thoughts on Government in 1776 to advocate a more conservative approach to republicanism.

Sophia Rosenfeld argues that Paine was highly innovative in his use of the commonplace notion of "common sense". He synthesized various philosophical and political uses of the term in a way that permanently impacted American political thought. He used two ideas from Scottish Common Sense Realism: that ordinary people can indeed make sound judgments on major political issues, and that there exists a body of popular wisdom that is readily apparent to anyone. Paine also used a notion of "common sense" favored by philosophes in the Continental Enlightenment. They held that common sense could refute the claims of traditional institutions. Thus, Paine used "common sense" as a weapon to delegitimize the monarchy and overturn prevailing conventional wisdom. Rosenfeld concludes that the phenomenal appeal of his pamphlet resulted from his synthesis of popular and elite elements in the independence movement.[36]

According to historian Robert Middlekauff, Common Sense became immensely popular mainly because Paine appealed to widespread convictions. Monarchy, he said, was preposterous, and it had a heathenish origin. It was an institution of the devil. Paine pointed to the Old Testament, where almost all kings had seduced the Israelites to worship idols instead of God. Paine also denounced aristocracy, which together with monarchy were "two ancient tyrannies". They violated the laws of nature, human reason, and the "universal order of things", which began with God. That was, Middlekauff says, exactly what most Americans wanted to hear. He calls the Revolutionary generation "the children of the twice-born",[37] because in their childhood they had experienced the Great Awakening, which, for the first time, had tied Americans together, transcending denominational and ethnic boundaries and giving them a sense of patriotism.[38][39]

The American Crisis (1776)

In late 1776, Paine published The American Crisis pamphlet series to inspire the Americans in their battles against the British army. He juxtaposed the conflict between the good American devoted to civic virtue and the selfish provincial man.[40] To inspire his soldiers, General George Washington had The American Crisis, first Crisis pamphlet, read aloud to them.[41] It begins:

These are the times that try men's souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value. Heaven knows how to put a proper price upon its goods; and it would be strange indeed if so celestial an article as freedom should not be highly rated.

Foreign affairs

In 1777, Paine became secretary of the Congressional Committee on Foreign Affairs. The following year, he alluded to secret negotiation underway with France in his pamphlets. His enemies denounced his indiscretions. There was scandal; together with Paine's conflict with Robert Morris and Silas Deane it led to Paine's expulsion from the Committee in 1779.[42]

However, in 1781, he accompanied John Laurens on his mission to France. Eventually, after much pleading from Paine, New York State recognized his political services by presenting him with an estate, at New Rochelle, New York, and Paine received money from Pennsylvania and from Congress at Washington's suggestion. During the Revolutionary War, Paine served as an aide to the important general, Nathanael Greene.

The Silas Deane Affair

In what may have been an error, and perhaps even contributed to his resignation as the secretary to the Committee of Foreign Affairs, Paine was openly critical of Silas Deane, an American diplomat who had been appointed in March 1776 by the Congress to travel to France in secret. Deane's goal was to influence the French government to finance the colonists in their fight for independence. Paine largely saw Deane as a war profiteer who had little respect for principle, having been under the employ of Robert Morris, one of the primary financiers of the American Revolution, and working with Pierre Beaumarchais, a French royal agent sent to the colonies by King Louis to investigate the Anglo-American conflict. Paine labelled Deane as unpatriotic, and demanded that there be a public investigation into Morris' financing of the Revolution, as he had contracted with his own company for around $500,000.

Unfortunately, Paine's criticisms turned against him. Amongst his criticisms, he had written in the Pennsylvania Packet that France had "prefaced [their] alliance by an early and generous friendship", referring to aid that had been provided to American colonies prior to the recognition of the Franco-American treaties. It was effectively an embarrassment on France, which potentially could have jeopardised the alliance. John Jay, the President of the Congress who had been a fervent supporter of Deane, immediately spoke out against Paine's comments. The controversy eventually became public, and Paine was then denounced as unpatriotic for criticising an American revolutionary. He was even physically assaulted twice in the street by Deane supporters. This much added stress took a large toll on Paine, who was generally of a sensitive character, and resigned as secretary to the Committee of Foreign Affairs in 1779.[43]

Funding the Revolution

Paine accompanied Col. John Laurens to France and is credited with initiating the mission.[44] It landed in France in March 1781 and returned to America in August with 2.5 million livres in silver, as part of a "present" of 6 million and a loan of 10 million. The meetings with the French king were most likely conducted in the company and under the influence of Benjamin Franklin. Upon returning to the United States with this highly welcomed cargo, Thomas Paine and probably Col. Laurens, "positively objected" that General Washington should propose that Congress remunerate him for his services, for fear of setting "a bad precedent and an improper mode". Paine made influential acquaintances in Paris, and helped organize the Bank of North America to raise money to supply the army.[45] In 1785, he was given $3,000 by the U.S. Congress in recognition of his service to the nation.[46]

Henry Laurens (the father of Col. John Laurens) had been the ambassador to the Netherlands, but he was captured by the British on his return trip there. When he was later exchanged for the prisoner Lord Cornwallis (in late 1781), Paine proceeded to the Netherlands to continue the loan negotiations. There remains some question as to the relationship of Henry Laurens and Thomas Paine to Robert Morris as the Superintendent of Finance and his business associate Thomas Willing who became the first president of the Bank of North America (in January 1782). They had accused Morris of profiteering in 1779 and Willing had voted against the Declaration of Independence. Although Morris did much to restore his reputation in 1780 and 1781, the credit for obtaining these critical loans to "organize" the Bank of North America for approval by Congress in December 1781 should go to Henry or John Laurens and Thomas Paine more than to Robert Morris.[47]

Paine bought his only house in 1783 on the corner of Farnsworth Avenue and Church Streets in Bordentown City, New Jersey, and he lived in it periodically until his death in 1809. This is the only place in the world where Paine purchased real estate. His design for a single-arch iron bridge[48] led him back to Europe after the Revolution, where he tried, unsuccessfully, to find backers for his plans.[5]

Rights of Man

Back in London by 1787, Paine became engrossed in the ongoing French Revolution that began in 1789. He visited France in 1790. Meanwhile, conservative intellectual Edmund Burke launched a counterrevolutionary blast against the French Revolution, entitled Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790); it strongly appealed to the landed class and sold 30,000 copies. Paine set out to refute it in his Rights of Man (1791). He wrote it not as a quick pamphlet but as a long, abstract political tract of 90,000 words that tore apart monarchies and traditional social institutions. On January 31, he gave the manuscript to publisher Joseph Johnson. A visit by government agents dissuaded Johnson, so Paine gave the book to publisher J.S. Jordan, then went to Paris, per William Blake's advice. He charged three good friends, William Godwin, Thomas Brand Hollis, and Thomas Holcroft, with handling publication details. The book appeared on March 13 and sold nearly a million copies. It was, "eagerly read by reformers, Protestant dissenters, democrats, London craftsman, and the skilled factory-hands of the new industrial north."[49]

Undeterred by the government campaign to discredit him, Paine issued his Rights of Man, Part the Second, Combining Principle and Practice in February 1792. It detailed a representative government with enumerated social programs to remedy the numbing poverty of commoners through progressive tax measures. Radically reduced in price to ensure unprecedented circulation, it was sensational in its impact and gave birth to reform societies. An indictment for seditious libel followed, for both publisher and author, while government agents followed Paine and instigated mobs, hate meetings, and burnings in effigy. A fierce pamphlet war also resulted, in which Paine was defended and assailed in dozens of works.[50] The authorities aimed, with ultimate success, to chase Paine out of Great Britain. He was then tried in absentia and found guilty though never executed.

In summer of 1792, he answered the sedition and libel charges thus: "If, to expose the fraud and imposition of monarchy ... to promote universal peace, civilization, and commerce, and to break the chains of political superstition, and raise degraded man to his proper rank; if these things be libellous ... let the name of libeller be engraved on my tomb."[51]

Paine was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, and was granted, along with Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and others, honorary French citizenship. Despite his inability to speak French, he was elected to the National Convention, representing the district of Pas-de-Calais.[52] He voted for the French Republic; but argued against the execution of Louis XVI, saying that he should instead be exiled to the United States: firstly, because of the way royalist France had come to the aid of the American Revolution; and secondly because of a moral objection to capital punishment in general and to revenge killings in particular. He participated in the Constitution Committee[53] that drafted the Girondin constitutional project.[54]

Regarded as an ally of the Girondins, he was seen with increasing disfavor by the Montagnards who were now in power, and in particular by Robespierre. A decree was passed at the end of 1793 excluding foreigners from their places in the Convention (Anacharsis Cloots was also deprived of his place). Paine was arrested and imprisoned in December 1793.

Thomas Paine wrote the second part of Rights of Man on a desk in Thomas 'Clio' Rickman's house, with whom he was staying in 1792 before he fled to France. This desk is currently on display in the People's History Museum in Manchester.[55]

The Age of Reason

Arrested in France, Paine protested and claimed that he was a citizen of America, which was an ally of Revolutionary France, rather than of Great Britain, which was by that time at war with France. However, Gouverneur Morris, the American minister to France, did not press his claim, and Paine later wrote that Morris had connived at his imprisonment. Paine narrowly escaped execution. A chalk mark, supposed to be left by the gaoler to denote that the prisoner in this cell was to be collected for execution, was left on the inside of his door, rather than the outside, as the door happened to be open as the gaoler made his rounds, because Paine was receiving official visitors. But for this quirk of fate, he would have died the following morning. He kept his head and survived the few vital days needed to be spared by the fall of Robespierre on 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794).[56]

Paine was released in November 1794 largely because of the work of the new American Minister to France, James Monroe,[57] who successfully argued the case for Paine's American citizenship.[58] In July 1795, he was re-admitted into the Convention, as were other surviving Girondins. Paine was one of only three députés to oppose the adoption of the new 1795 constitution, because it eliminated universal suffrage, which had been proclaimed by the Montagnard Constitution of 1793.[59]

In 1797, Tom Paine lived in Paris with Nicholas Bonneville and his wife. Paine, as well as Bonneville's other controversial guests, aroused the suspicions of authorities. Bonneville hid the Royalist Antoine Joseph Barruel-Beauvert at his home. Beauvert had been outlawed following the coup of 18 Fructidor on September 4, 1797. Paine believed that America, under President John Adams, had betrayed revolutionary France.[60] Bonneville was then briefly jailed and his presses were confiscated, which meant financial ruin.

In 1800, still under police surveillance, Bonneville took refuge with his father in Evreux. Paine stayed on with him, helping Bonneville with the burden of translating the "Covenant Sea". The same year, Paine purportedly had a meeting with Napoleon. Napoleon claimed he slept with a copy of Rights of Man under his pillow and went so far as to say to Paine that "a statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe."[61] Paine discussed with Napoleon how best to invade England and in December 1797 wrote two essays, one of which was pointedly named Observations on the Construction and Operation of Navies with a Plan for an Invasion of England and the Final Overthrow of the English Government,[62] in which he promoted the idea to finance 1,000 gunboats to carry a French invading army across the English Channel. In 1804 Paine returned to the subject, writing To the People of England on the Invasion of England advocating the idea.[60]

On noting Napoleon's progress towards dictatorship, he condemned him as: "the completest charlatan that ever existed".[63] Paine remained in France until 1802, returning to the United States only at President Jefferson's invitation.

Criticism of George Washington

Paine believed that U.S. President George Washington had conspired with Robespierre to imprison him. He had felt largely betrayed that Washington, who had been a lifelong friend, did nothing whilst Paine suffered in prison. Whilst staying with Monroe, he planned to send Washington a letter of grievance on the former President's birthday. Monroe stopped the letter from being sent just in time, and, after Paine's criticism of the Jay Treaty, Monroe suggested that Paine reside somewhere else.[64]

Still embittered by this perceived betrayal by Washington, Paine tried to ruin his reputation by calling him a treacherous man unworthy of his fame as a military and political hero. He sent a stinging letter to Washington, in which Paine described him as an incompetent commander and a vain and ungrateful person. Paine never received a reply, so he contacted his lifelong publisher, the anti-Federalist Benjamin Bache to publish this Letter to George Washington in 1796. In this scathing publication, Paine wrote: "the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an impostor; whether you have abandoned good principles or whether you ever had any."[65] He had written rather that without the aid of France, Washington could not have succeeded in the Revolution and that he had "but little share in the glory of the final event". He also commented on Washington's poor character, saying that he has no sympathetic feelings and is a hypocrite.[66]

Later years

In 1802 or 1803, Paine left France for the United States, paying passage also for Bonneville's wife, Marguerite Brazier and their three sons, seven-year-old Benjamin, Louis, and Thomas, to whom Paine was godfather. Paine returned to the United States in the early stages of the Second Great Awakening and a time of great political partisanship. The Age of Reason gave ample excuse for the religiously devout to dislike him, and the Federalists attacked him for his ideas of government stated in Common Sense, for his association with the French Revolution, and for his friendship with President Jefferson. Also still fresh in the minds of the public was his Letter to Washington, published six years before his return. This was compounded when his right to vote was denied in New Rochelle on the grounds that Gouverneur Morris did not recognize him as an American, and Washington had not aided him.[67]

Brazier took care of Paine at the end of his life and buried him after his death on June 8, 1809. In his will, Paine left the bulk of his estate to Marguerite, including 100 acres (40.5 ha) of his farm so she could maintain and educate Benjamin and his brother Thomas. In 1814, the fall of Napoleon finally allowed Bonneville to rejoin his wife in the United States where he remained for four years before returning to Paris to open a bookshop.

Death

Paine died at the age of 72, at 59 Grove Street in Greenwich Village, New York City, on the morning of June 8, 1809. Although the original building is no longer there, the present building has a plaque noting that Paine died at this location.

After his death, Paine's body was brought to New Rochelle, but the Quakers would not allow it to be buried in their grave-yard as per his last will, so his remains were buried under a walnut tree on his farm. In 1819, the English agrarian radical journalist William Cobbett, who in 1793 had published a hostile continuation[68] of Francis Oldys (George Chalmer)'s The Life of Thomas Paine,[69] dug up his bones and transported them back to England with the intention to give Paine a heroic reburial on his native soil, but this never came to pass. The bones were still among Cobbett's effects when he died over twenty years later, but were later lost. There is no confirmed story about what happened to them after that, although various people have claimed throughout the years to own parts of Paine's remains, such as his skull and right hand.[70][71][72]

At the time of his death, most American newspapers reprinted the obituary notice from the New York Evening Post,[73] which read in part: "He had lived long, did some good, and much harm." Only six mourners came to his funeral, two of whom were black, most likely freedmen. The writer and orator Robert G. Ingersoll wrote:

Thomas Paine had passed the legendary limit of life. One by one most of his old friends and acquaintances had deserted him. Maligned on every side, execrated, shunned and abhorred – his virtues denounced as vices – his services forgotten – his character blackened, he preserved the poise and balance of his soul. He was a victim of the people, but his convictions remained unshaken. He was still a soldier in the army of freedom, and still tried to enlighten and civilize those who were impatiently waiting for his death. Even those who loved their enemies hated him, their friend – the friend of the whole world – with all their hearts. On the 8th of June, 1809, death came – Death, almost his only friend. At his funeral no pomp, no pageantry, no civic procession, no military display. In a carriage, a woman and her son who had lived on the bounty of the dead – on horseback, a Quaker, the humanity of whose heart dominated the creed of his head – and, following on foot, two negroes filled with gratitude – constituted the funeral cortege of Thomas Paine.[74]

Ideas

Biographer Eric Foner identifies a utopian thread in Paine's thought, writing that "Through this new language he communicated a new vision—a utopian image of an egalitarian, republican society."[75] Paine's utopianism combined civic republicanism, belief in the inevitability of scientific and social progress and commitment to free markets and liberty generally. The multiple sources of Paine's political theory all pointed to a society based on the common good and individualism. Paine expressed a redemptive futurism or political messianism.[76] Paine, writing that his generation "would appear to the future as the Adam of a new world", exemplified British utopianism.[77]

Thomas Paine's natural justice beliefs may have been influenced by his Quaker father.[78]

Later, his encounters with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas made a deep impression. The ability of the Iroquois to live in harmony with nature while achieving a democratic decision-making process helped him refine his thinking on how to organize society.[79]

Slavery

Paine is sometimes credited with writing "African Slavery in America", the first article proposing the emancipation of African slaves and the abolition of slavery. It was published on March 8, 1775, in the Postscript to the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser (aka The Pennsylvania Magazine and American Museum).[80] Citing a lack of evidence that Paine was the author of this anonymously published essay, some scholars (Eric Foner and Alfred Owen Aldridge) no longer consider this one of his works. By contrast, John Nichols speculates that his "fervent objections to slavery" led to his exclusion from power during the early years of the Republic.[81]

Agrarian Justice

His last pamphlet, Agrarian Justice, opposed to Agrarian Law, and to Agrarian Monopoly, published in the winter of 1795, further developed his ideas in the Rights of Man, about how land ownership separated the majority of people from their rightful, natural inheritance and means of independent survival. The US Social Security Administration recognizes Agrarian Justice as the first American proposal for an old-age pension and basic income; per Agrarian Justice:

In advocating the case of the persons thus dispossessed, it is a right, and not a charity ... [Government must] create a national fund, out of which there shall be paid to every person, when arrived at the age of twenty-one years, the sum of fifteen pounds sterling, as a compensation in part, for the loss of his or her natural inheritance, by the introduction of the system of landed property. And also, the sum of ten pounds per annum, during life, to every person now living, of the age of fifty years, and to all others as they shall arrive at that age.

Note that £10 and £15 would be worth about £800 and £1,200 ($1,200 and $2,000) when adjusted for inflation (2011 British Pounds Sterling).[82]

Lamb argues that Paine's analysis of property rights marks a distinct contribution to political theory. His theory of property defends a libertarian concern with private ownership that shows an egalitarian commitment. Paine's new justification of property sets him apart from previous theorists such as Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, and John Locke. It demonstrates Paine's commitment to foundational liberal values of individual freedom and moral equality.[83]

Religious views

Before his arrest and imprisonment in France, knowing that he would probably be arrested and executed, Paine, following in the tradition of early eighteenth-century British deism, wrote the first part of The Age of Reason, an assault on organized "revealed" religion combining a compilation of the many inconsistencies he found in the Bible.

About his own religious beliefs, Paine wrote in The Age of Reason:

I believe in one God, and no more; and I hope for happiness beyond this life.

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church. All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.[84]

Though there is no evidence he was himself a Freemason,[85] upon his return to America from France, Paine also penned "An Essay on the Origin of Free-Masonry" (1803–1805), about Freemasonry being derived from the religion of the ancient Druids.[86] In the essay, he stated that "The Christian religion is a parody on the worship of the sun, in which they put a man called Christ in the place of the sun, and pay him the adoration originally paid to the sun." Marguerite de Bonneville published the essay in 1810, after Paine's death, but she chose to omit certain passages from it that were critical of Christianity, most of which were restored in an 1818 printing.[87]

While Paine never described himself as a deist,[87] he did write the following:

The opinions I have advanced ... are the effect of the most clear and long-established conviction that the Bible and the Testament are impositions upon the world, that the fall of man, the account of Jesus Christ being the Son of God, and of his dying to appease the wrath of God, and of salvation, by that strange means, are all fabulous inventions, dishonorable to the wisdom and power of the Almighty; that the only true religion is Deism, by which I then meant, and mean now, the belief of one God, and an imitation of his moral character, or the practice of what are called moral virtues – and that it was upon this only (so far as religion is concerned) that I rested all my hopes of happiness hereafter. So say I now – and so help me God.[47]

Legacy

Paine's writing greatly influenced his contemporaries and, especially, the American revolutionaries. His books provoked an upsurge in Deism in America, but in the long term inspired philosophic and working-class radicals in the UK and US. Liberals, libertarians, feminists, democratic socialists, social democrats, anarchists, free thinkers, and progressives often claim him as an intellectual ancestor. Paine's critique of institutionalized religion and advocacy of rational thinking influenced many British free thinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as William Cobbett, George Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh, Christopher Hitchens and Bertrand Russell.

The quote "Lead, follow, or get out of the way" is widely but incorrectly attributed to Paine. This can be found nowhere in his published works.

In 2002, Paine was voted number 34 of "100 Greatest Britons" in a public poll conducted by the BBC.

Lincoln

When Abraham Lincoln was 26 years old in 1835, he wrote a defense of Paine's deism; a political associate, Samuel Hill, burned it to save Lincoln's political career.[88] Historian Roy Basler, the editor of Lincoln's papers, said Paine had a strong influence on Lincoln's style:

- No other writer of the eighteenth century, with the exception of Jefferson, parallels more closely the temper or gist of Lincoln's later thought. In style, Paine above all others affords the variety of eloquence which, chastened and adapted to Lincoln's own mood, is revealed in Lincoln's formal writings.[89]

Edison

The inventor Thomas Edison said:

I have always regarded Paine as one of the greatest of all Americans. Never have we had a sounder intelligence in this republic ... It was my good fortune to encounter Thomas Paine's works in my boyhood ... it was, indeed, a revelation to me to read that great thinker's views on political and theological subjects. Paine educated me, then, about many matters of which I had never before thought. I remember, very vividly, the flash of enlightenment that shone from Paine's writings, and I recall thinking, at that time, 'What a pity these works are not today the schoolbooks for all children!' My interest in Paine was not satisfied by my first reading of his works. I went back to them time and again, just as I have done since my boyhood days.[90]

South America

In 1811, Venezuelan translator Manuel Garcia de Sena published a book in Philadelphia which consisted mostly of Spanish translations of several of Paine's most important works.[91] The book also included translations of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Constitution, and the constitutions of five U.S. states.[91] It subsequently circulated widely in South America, and through it, Uruguayan national hero José Gervasio Artigas became familiar with and embraced Paine's ideas.[91] In turn, many of Artigas's writings drew directly from Paine's, including the Instructions of 1813, which Uruguayans consider to be one of their country's most important constitutional documents; it was one of the earliest writings to articulate a principled basis for an identity independent of Buenos Aires.[91]

Memorials

The first and longest standing memorial to Thomas Paine is the carved and inscribed 12 foot marble column in New Rochelle, New York organized and funded by publisher, educator and reformer Gilbert Vale (1791–1866) and raised in 1839 by the American sculptor and architect John Frazee — the Thomas Paine Monument (see image below).[92]

New Rochelle is also the original site of Thomas Paine's Cottage, which, along with a 320-acre (130 ha) farm, were presented to Paine in 1784 by act of the New York State Legislature for his services in the American Revolution.[93]

The same site is the home of the Thomas Paine Memorial Museum. Thomas A. Edison helped to turn the first shovel of earth for the museum which serves as a museum to display both Paine relics as well as others of local historical interest. A large collection of books, pamphlets, and pictures is contained in the Paine library, including many first editions of Paine's works, as well as several original manuscripts. These holdings, the subject of a sell-off controversy, were temporarily relocated to the New-York Historical Society and have since been more permanently archived in the Iona College library nearby.[94]

Paine was originally buried near the current location of his house and monument upon his death in 1809. The site is marked by a small headstone and burial plaque even though his remains were said to have been removed to England years later.

In the twentieth century, Joseph Lewis, longtime president of the Freethinkers of America and an ardent Paine admirer, was instrumental in having larger-than-life-sized statues of Paine erected in each of the three countries with which the revolutionary writer was associated. The first, created by Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum, was erected in Paris just before World War II began (but not formally dedicated until 1948). It depicts Paine standing before the French National Convention to plead for the life of King Louis XVI. The second, sculpted in 1950 by Georg J. Lober, was erected near Paine's one time home in Morristown, New Jersey. It shows a seated Paine using a drum-head as a makeshift table. The third, sculpted by Sir Charles Wheeler, President of the Royal Academy, was erected in 1964 in Paine's birthplace, Thetford, England. With quill pen in his right hand and an inverted copy of The Rights of Man in his left, it occupies a prominent spot on King Street. Thomas Paine was ranked #34 in the 100 Greatest Britons 2002 extensive Nationwide poll conducted by the BBC.[95]

A bronze plaque attached to the wall of Thetford's Tom Paine hotel gives details of Paine's life. It was placed there in 1943 by voluntary contributions from US airmen from a nearby bomber base. Texas folklorist and freethinker J. Frank Dobie, then teaching at Cambridge University, participated in the dedication ceremonies.[96]

Bronx Community College includes Paine in its Hall of Fame of Great Americans, and there are statues of Paine in Morristown and Bordentown, New Jersey, and in the Parc Montsouris, in Paris.[97][98]

In Paris, there is a plaque in the street where he lived from 1797 to 1802, that says: "Thomas PAINE / 1737–1809 / Englishman by birth / American by adoption / French by decree".

Yearly, between July 4 and 14, the Lewes Town Council in the United Kingdom celebrates the life and work of Thomas Paine.[99]

In the early 1990s, largely through the efforts of citizen activist David Henley of Virginia, legislation (S.Con.Res 110, and H.R. 1628) was introduced in the 102nd Congress by ideological opposites Sen. Steve Symms (R-ID) and Rep. Nita Lowey (D-NY). With over 100 formal letters of endorsement by US and foreign historians, philosophers and organizations, including the Thomas Paine National Historical Society, the legislation garnered 78 original co-sponsors in the Senate and 230 original co-sponsors in the House of Representatives, and was consequently passed by both houses' unanimous consent. In October 1992 the legislation was signed into law (PL102-407 & PL102-459) by President George H. W. Bush authorizing the construction, using private funds, of a memorial to Thomas Paine in "Area 1" of the grounds of the US Capitol. As of January 2011[update], the memorial has not yet been built.

The University of East Anglia's Norwich Business School is housed in the Thomas Paine Study Centre on its Norwich campus, in Paine's home county of Norfolk.[100]

The Cookes House is reputed to have been his home during the Second Continental Congress at York, Pennsylvania.[101]

-

John Frazee's Thomas Paine Monument in New Rochelle

-

Statue in Bordentown, New Jersey

-

Plaque honoring Paine at 10 rue de l'Odéon, Paris

-

Plaque on Thomas Paine Hotel, Thetford

-

Commemorative plaque on the site of the former residence of Paine in Greenwich Village, New York City

In popular culture

- The 1982 French-Italian film That Night in Varennes is about a fictional meeting of Casanova, Chevalier de Seingalt (played by Italian actor Marcello Mastroianni), Nicolas Edmé Restif de la Bretonne, Countess Sophie de la Borde, and Thomas Paine (played by American actor Harvey Keitel) as they ride in a carriage a few hours behind the carriage carrying the King and Queen of France, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, on their attempt to escape from revolutionary France in 1791.

- Jack Shepherd's stage play In Lambeth dramatized a visit by Thomas Paine to the Lambeth home of William and Catherine Blake in 1789.

- In 1995, English folk singer Graham Moore, from Dorset, wrote "Tom Paine's Bones" which he recorded on his album of the same name.[102][103] In 2001 the Scottish musician Dick Gaughan included the song on his album Outlaws and Dreamers.

- In 2005 the writer Trevor Griffiths published These are the Times: A Life of Thomas Paine, originally written as a screenplay for Richard Attenborough Productions. Although the film was not made, the play was broadcast, as a two-part drama, on BBC Radio 4 in 2008[104] with a repeat in 2012.[105] In 2009 Griffiths adapted the screenplay for a production entitled A New World at Shakespeare's Globe theatre on London's South Bank.[106]

- In 2009 Paine's life was dramatized in the play Thomas Paine Citizen of the World,[107] produced for the "Tom Paine 200 Celebrations" festival[108] in Thetford, the town of his birth.

- Paine's role in the foundation of the United States is depicted in a pseudo-biographical fashion in the educational animated series Liberty's Kids produced by DIC Entertainment.

- Paine is a character in the Bob Dylan song "As I Went Out One Morning", featured on Dylan's 1968 album, John Wesley Harding.

- Paine is also mentioned in the song "Renegades of Funk" by Afrika Bambaataa in which he is referred to as "Tom Paine" among other notable "renegades" Chief Sitting Bull, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. The song was later covered by rap metal band Rage Against the Machine, with Paine's name still included.

- Paine is referred to on several occasions in Philip Roth's 1998 novel I Married a Communist.

- Paine is a character in the story "Thermidor" in The Sandman: Fables & Reflections, where he is shown having a colloquy with Louis Antoine de Saint-Just.

- Paine is referred to in the song "Think About It" by Semi Hendrix, a collaboration album by Ras Kass and Jack Splash.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Conway, Moncure D. (1908). The Life of Thomas Paine. Vol. Vol. I. p. 3. Cobbett, William, Illustrator. G. P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is printed in Volume I, page 3, as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. Paine's birth date, between January 1, and March 25, advances by eleven days and his year increases by one to February 9, 1737. The O.S. link gives more detail if needed. - ^ Contemporary records, which used the Julian calendar and the Annunciation Style of enumerating years, recorded his birth as January 29, 1736. The provisions of the British Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, implemented in 1752, altered the official British dating method to the Gregorian calendar with the start of the year on January 1 (it had been March 25). These changes resulted in dates being moved forward 11 days, and for those between January 1 and March 25, an advance of one year. For a further explanation, see: Old Style and New Style dates.

- ^ Engber, Daniel (January 18, 2006). "What's Benjamin Franklin's Birthday?". Slate. Retrieved May 21, 2011. (Both Franklin's and Paine's confusing birth dates are clearly explained.)

References

- ^ a b Ayer, Alfred Jules (1990). Thomas Paine. University of Chicago Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-226-03339-2.

- ^ Henretta, James A.; et al. (2011). America's History, Volume 1: To 1877. Macmillan. p. 165. ISBN 9780312387914.

- ^ Jason D. Solinger. "Thomas Paine's Continental Mind". Early American Literature (2010) 45#3, Vol. 45 Issue 3, pp. 593-61.7

- ^ Saul K. Padover, Jefferson: A Great American's Life and Ideas, (1952), p. 32.

- ^ a b c Hitchens, Christopher (2006). Thomas Paine's Rights of Man. Grove Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-8021-4383-0.

- ^ Biographer Harvey Kaye writes, "Within just a few months 150,000 copies of one or another edition were distributed in America alone. The equivalent sales today would be fifteen million, making it, proportionally, the nation's greatest best-seller ever." in Kaye, Harvey J. (2005). Thomas Paine And The Promise of America. Hill & Wang. p. 43. ISBN 0-8090-9344-8.

- ^ The Sharpened Quill, The New Yorker. Accessed November 6, 2010.

- ^ Conway, Moncure D. (1892). The Life of Thomas Paine. Vol. 2, pp. 417–418.

- ^ Crosby, Alan (1986). A History of Thetford (1st ed.). Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore & Co Ltd. pp. 44–84. ISBN 0-85033-604-X. (Also see discussion page)

- ^ "National Archives". UK National Archives. Acknowledgement dated Mar 2, 1769, document NU/1/3/3

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ School History Thetford Grammar School, Accessed January 3, 2008,

- ^ "Word List: Definitions of Nautical Terms and Ship Parts". Phrontistery.info. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ "Thetford Tourist Infomation [sic] Centre | Information Centre | Thetford|Norfolk". Visitnorfolk.co.uk. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ Rights of Man II, Chapter V.

- ^ Thomas had intended to serve under the ill-fated Captain William Death but was dissuaded by his father. Bring the Paine!

- ^ "Thomas Paine". Sandwich People & History. Open Sandwich. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- ^ Conway, Moncure Daniel (1892). "The Life of Thomas Paine: With a History of Literary, Political, and Religious Career in America, France, and England". Thomas Paine National Historical Association. p. Vol. 1, p. 20. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ^ Kaye, Harvey J. (2000). Thomas Paine: Firebrand of the Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0195116275.

- ^ "Letter to the Honorable Henry Laurens" in Philip S. Foner's The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine (New York: Citadel Press, 1945), 2:1160–65.

- ^ Conway, Moncure Daniel, 1892. The Life of Thomas Paine vol. 1, p. 209.

- ^ History of Bridge Engineering, H. G. Tyrrell, Chicago, 1911

- ^ A biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland at 753–755, A. W. Skempton and M. Chrimes, ed.,Thomas Telford, 2002 (ISBN 0-7277-2939-X, 9780727729392)

- ^ See Thomas Paine, Independence Hall Association. Accessed online November 4, 2006.

- ^ K. M. Kostyal. Funding Fathers: The Fight for Freedom and the Birth of American Liberty (2014) ch 2

- ^ David Braff, "Forgotten Founding Father: The Impact of Thomas Paine," in Joyce Chumbley, ed., Thomas Paine: In Search of the Common Good (2009).

- ^ Oliphant, John. "Paine,Thomas". Encyclopedia of the American Revolution: Library of Military History. Charles Scribner's Sons (accessed via Gale Virtual Library). Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ^ Robert A. Ferguson (July 2000). "The Commonalities of Common Sense". William and Mary Quarterly. 57#3: 465–504. JSTOR 2674263.

- ^ Philp, Mark (2013). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). "Thomas Paine". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2013 Edition). Retrieved January 24, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Merrill Jensen, The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution, 1763–1776 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), 668.

- ^ David C. Hoffman, "Paine and Prejudice: Rhetorical Leadership through Perceptual Framing in Common Sense". Rhetoric and Public Affairs, Fall 2006, Vol. 9, Issue 3, pp. 373–410.

- ^ Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Knopf, 1997), 90–91.

- ^ Jack N. Rakove, The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress (New York: Knopf, 1979), 89.

- ^ Jack S. Levy, William R. Thompson, Causes of War (John Wiley & Sons, 2011)

- ^ New, M. Christopher. "James Chalmers and Plain Truth A Loyalist Answers Thomas Paine". "Archiving Early America". Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- ^ Jensen, Founding of a Nation, 669.

- ^ Sophia Rosenfeld, "Tom Paine's Common Sense and Ours". William and Mary Quarterly (2008), 65#4, pp. 633-668 in JSTOR

- ^ Robert Middlekauff (2005), The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789, Revised and Expanded Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y., ISBN 978-0-19-531588-2, pp. 30-53.

- ^ Robert Middlekauff, The Glorious Cause, pp. 4-5, 324-326.

- ^ Cf. Clifton E. Olmstead (1960), History of Religion in the United States, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., p. 178.

- ^ Martin Roth, "Tom Paine and American Loneliness". Early American Literature, September 1987, Vol. 22, Issue 2, pp. 175–82.

- ^ "Thomas Paine. The American Crisis. Philadelphia, Styner and Cist, 1776–77". Indiana University. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Nelson, Craig (2007). Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. Penguin. pp. 174–75.

- ^ Craig Nelson. Thomas Paine. pp. 134–138. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- ^ Daniel Wheeler's Life and Writings of Thomas Paine Vol. 1 (1908) pp. 26–27.

- ^ Daniel Wheeler's Life and Writings of Thomas Paine Vol. 1 (1908), p. 314.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (2005). Common Sense and Other Writings. Barnes & Noble Classics. p. xiii. ISBN 0-672-60004-8.

- ^ a b Thomas Paine (1824), The Theological Works of Thomas Paine, R. Carlile ... and, p. 138

- ^ Yorkshire Stingo

- ^ George Rudé, Revolutionary Europe: 1783 – 1815 (1964), p. 183.

- ^ Many of these are reprinted in Political Writings of the 1790s, ed. G. Claeys (8 vols, London: Pickering and Chatto, 1995).

- ^ Thomas Paine, Letter Addressed To The Addressers On The Late Proclamation, in Michael Foot, Isaac Kramnick (ed.), The Thomas Paine Reader, p. 374

- ^ Fruchtman, Jack (2009). The Political Philosophy of Thomas Paine. Baltimore, MD, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0-8018-9284-8.

- ^ Girondist

- ^ "Thomas Paine 1793 Girondin Constitution draft - Google Search". Google Search. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ Collection highlights, Tom Paine's Desk, People's History Museum

- ^ Paine, Thomas; Rickman, Thomas Clio (1908). "The Life and Writings of Thomas Paine: Containing a Biography". Vincent Parke & Co.: 261–262. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Foot, Michael, and Kramnick, Isaac. 1987. The Thomas Paine Reader, p.16

- ^ Eric Foner, 1976. Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. p. 244.

- ^ Aulard, Alphonse. 1901. Histoire politique de la Révolution française, p. 555.

- ^ a b "Mark Philp, 'Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2008, accessed July 26, 2008".

- ^ O'Neill, Brendan (June 8, 2009). "Who was Thomas Paine?". BBC. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Papers of James Monroe... from the original manuscripts in the Library of Congress".

- ^ Craig Nelson. Thomas Paine. p. 299. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- ^ Craig Nelson. Thomas Paine. p. 291. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- ^ Paine, Thomas. "Letter to George Washington, July 30, 1796: "On Paine's Service to America"". Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved November 4, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Craig Nelson. Thomas Paine. pp. 292–294. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- ^ Claeys, Gregory, 1989. Thomas Paine, Social and Political Thought.

- ^ William Cobbett, The Life of Thomas Paine, Interspersed with Remarks and Reflections (London: J. Wright, 1797)

- ^ "Francis Oldys" [George Chalmers], The Life of Thomas Paine. One Penny-Worth of Truth, from Thomas Bull to His Brother John (London: Stockdale, 1791)

- ^ "The Paine Monument at Last Finds a Home". The New York Times. October 15, 1905. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ Chen, David W. "Rehabilitating Thomas Paine, Bit by Bony Bit". The New York Times. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ Burrows, Edwin G. and Wallace, Mike. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999., p. 510.

- ^ "Paine's Obituary (click the "1809" link; it is 1/3 way down the 4th column)". New York Evening Post. June 10, 1809. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (2008). Works of Thomas Paine. MobileReference. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Eric Foner (2005). Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press, 2nd edition. p. xxxii, 16. ISBN 9780195174861.

- ^ Mark Jendrysik, "Tom Paine: Utopian?" Utopian Studies (2007) 18#2 pp. 139-157.

- ^ Gregory Claeys, ed. (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9781139828420.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Claeys p. 20.

- ^ Weatherford, Jack "Indian Givers How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World". 1988, p. 125.

- ^ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Slavery in the United States: A Social, Political, and Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 279.

- ^ Nichols, John (January 20, 2009). "Obama's Vindication of Thomas Paine". The Nation.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present". Measuringworth.com. February 15, 1971. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ Lamb, Robert. "Liberty, Equality, and the Boundaries of Ownership: Thomas Paine's Theory of Property Rights". Review of Politics (2010), 72#3 pp. 483–511.

- ^ Thomas Paine (1824). The Theological Works of Thomas Paine. R. Carlile et al. p. 31.

- ^ Shai Afsai (Fall 2010). "Thomas Paine's Masonic Essay and the Question of His Membership in the Fraternity" (PDF). Philalethes 63 (4): 138–144. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

As he was certainly not a Master Mason when he wrote the essay—and as there is no evidence he joined the fraternity after then—one may conclude, as have Mackey, Newton, and others, that Paine was not a Freemason. Still, though the 'pantheon of Masons' may not hold Thomas Paine, this influential and controversial man remains connected to Freemasonry, if only due to the close friendships he had with some in the fraternity, and to his having written an intriguing essay on its origins.

- ^ Shai Afsai, "Thomas Paine's Masonic Essay and the Question of His Membership in the Fraternity". Philalethes 63:4 (Fall 2010), 140–141.

- ^ a b Afsai, Shai (2012). "Thomas Paine, Freemason or Deist?". Early America Review (Winter/Spring).

- ^ Michael Burlingame, Abraham Lincoln: a life (2008), vol. 2, p. 83.

- ^ Roy P. Basler (ed.), Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings (1946), p. 6.

- ^ Thomas Edison, Introduction to The Life and Works of Thomas Paine, New York: Citadel Press, 1945, Vol. I, pp. vii-ix. Reproduced online on thomaspaine.org, accessed November 4, 2006.

- ^ a b c d John Street, Artigas and the Emancipation of Uruguay (London: Cambridge University Press, 1959), 178-186.

- ^ See Frederick S. Voss, John Frazee 1790–1852 Sculptor (Washington City and Boston: The National Portrait Gallery and The Boston Athenaeum, 1986), 46–47.

- ^ See Alfred Owen Aldridge, Man of Reason (Philadelphia: J.P. Lippincott Company, 1959), 103.

- ^ [1] Archived 2013-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "BBC – 100 Great British Heroes". BBC News. August 21, 2002. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ J. Frank Dobie, A Texan in England. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1980, pp.84-5.

- ^ "Photos of Tom Paine and Some of His Writings". Morristown.org. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ "Parc Montsouris". Paris Walking Tours. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ The Tom Paine Project, Lewes Town Council. Retrieved November 4, 2006.

- ^ "Thomas Paine Study Centre - University of East Anglia (UEA)". uea.ac.uk. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania" (Searchable database). CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Note: This includes Pennsylvania Register of Historic Sites and Landmarks (March 1972). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Cookes House" (PDF). Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ Graham Moore. "Heart of Darkness".

- ^ "Graham Moore blogspot".

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Saturday Drama - Episodes by". Bbc.co.uk. August 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Saturday Drama - Episodes by". Bbc.co.uk. August 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/education/discovery-space/previous-productions/new-world

- ^ "Thomas Paine - "Citizen Of The World"". Keystage-company.co.uk. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ Tom Paine Legacy, Programme for bicentenary celebrations.

Bibliography

- Aldridge, A. Owen (1959). Man of Reason: The Life of Thomas Paine. Lippincott.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). Regarded by British authorities as the standard biography. - Aldridge, A. Owen (1984). Thomas Paine's American Ideology. University of Delaware Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ayer, A. J. (1988). Thomas Paine. University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bailyn, Bernard (1990). Bailyn (ed.). Common Sense. Alfred A. Knopf.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernstein, R. B. (1994). "Review Essay: Rediscovering Thomas Paine". New York Law School Law Review.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). Valuable blend of historiographical essay and biographical/analytical treatment. - Butler, Marilyn (1984). Burke Paine and Godwin and the Revolution Controversy.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Claeys, Gregory (1989). Thomas Paine, Social and Political Thought. London: Unwin Hyman.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). Excellent analysis of Paine's thought. - Conway, Moncure Daniel (1892). "The Life of Thomas Paine". G.P. Putnam's Sons.. Long hailed as the definitive biography, and still valuable.

- Ferguson, Robert A. (July 2000). "The Commonalities of Common Sense". William and Mary Quarterly. 57#3.

- Foner, Eric (1976). Tom Paine and Revolutionary America. Oxford University Press.. The standard monograph treating Paine's thought and work with regard to America.

- Foner, Eric (2000). Thomas Paine. American National Biography Online.

- Griffiths, Trevor (2005). These Are the Times: A Life of Thomas Paine. Spokesman Books.

- Hawke, David Freeman (1974). Paine. Philadelphia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Regarded by many American authorities as the standard biography. - Hitchens, Christopher (2006). Thomas Paine's "Rights of Man": A Biography. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kates, Gary (1989). "From Liberalism to Radicalism: Tom Paine's Rights of Man". Journal of the History of Ideas.

- Kaye, Harvey J. (2005). Thomas Paine and the Promise of America. Hill and Wang.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keane, John (1995). Tom Paine: A Political Life. London.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). One of the most valuable recent studies. - Lamb, Robert (2010). "Liberty, Equality, and the Boundaries of Ownership: Thomas Paine's Theory of Property Rights". Review of Politics. 72 (3).

- Larkin, Edward (2005). Thomas Paine and the Literature of Revolution. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lessay, Jean (1987). L'américain de la Convention, Thomas Paine: Professeur de révolutions (in French). Paris: Éditions Perrin. p. 241.

- Levin, Yuval (2013). The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left. Basic Books. p. 275.. Their debate over the French Revolution.

- Lewis, Joseph L. (1947). Thomas Paine: The Author of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Freethought Press Association.

- Nelson, Craig (2006). Thomas Paine: Enlightenment, Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Nations. Viking. ISBN 0-670-03788-5.

- Phillips, Mark (May 2008). "Paine, Thomas (1737–1809)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21133. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- Powell, David (1985). Tom Paine, The Greatest Exile. Hutchinson.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Russell, Bertrand (1934). "The Fate of Thomas Paine".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Solinger, Jason D. (November 2010). "Thomas Paine's Continental Mind". Early American Literature. 45 (3).

- Vincent, Bernard (2005). The Transatlantic Republican: Thomas Paine and the age of revolutions.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilensky, Mark (2008). The Elementary Common Sense of Thomas Paine. An Interactive Adaptation for All Ages. Casemate. ISBN 978-1-932714-36-4.

- Washburne, E. B. (May 1880). "Thomas Paine and the French Revolution". Scribner's Monthly. XX.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link)

Fiction

- Fast, Howard (1946). Citizen Tom Paine.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (historical novel, though sometimes mistaken as biography).

Primary sources

- Paine, Thomas (1896). Conway, Moncure Daniel (ed.). The Writings of Thomas Paine, Volume 4.

G. P. Putnam's sons, New York. p. 521., E'book - Foot, Michael; Kramnick, Isaac (1987). The Thomas Paine Reader. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044496-3.

- Paine, Thomas (1993). Foner, Eric (ed.). Writings. Philadelphia: Library of America.. Authoritative and scholarly edition containing Common Sense, the essays comprising the American Crisis series, Rights of Man, The Age of Reason, Agrarian Justice, and selected briefer writings, with authoritative texts and careful annotation.

- Paine, Thomas (1944). Foner, Philip S. (ed.). The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine. Vol. 2 vols. Citadel Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) We badly need a complete edition of Paine's writings on the model of Eric Foner's edition for the Library of America, but until that goal is achieved, Philip Foner's two-volume edition is a serviceable substitute. Volume I contains the major works, and volume II contains shorter writings, both published essays and a selection of letters, but confusingly organized; in addition, Foner's attributions of writings to Paine have come in for some criticism in that Foner may have included writings that Paine edited but did not write and omitted some writings that later scholars have attributed to Paine.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (May 2015) |

- "Common Sense: The Rhetoric of Popular Democracy" lesson plan for grades 9-12 from National Endowment for the Humanities

- The UK Thomas Paine Society

- The Thomas Paine Society

- Who was Thomas Paine?

- Essays on the Religious and Political Philosophy of Thomas Paine

- Thomas Paine's Memorial

- Thomas Paine Quotations

- Take a video tour of Thomas Paine's birthplace

- Office location while in Alford[dead link]

- Archived 2012-08-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas Paine on Paper Money, 1786

- Thomas Paine, Liberty's Hated Torchbearer

- Lesson plan – Common Sense: The Rhetoric of Popular Democracy

- Correspondence between Paine and Samuel Adams regarding the charge of infidelity

- One Life: Thomas Paine, the Radical Founding Father, exhibition from the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

- Thomas Paine at C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- "Archival material relating to Thomas Paine". UK National Archives.

- Portraits of Thomas Paine at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Works

- Works by Thomas Paine at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Paine at the Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Paine at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Deistic and Religious Works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine

- The theological works of Thomas Paine to which are appended the profession of faith of a savoyard vicar by J.J. Rousseau

- Common Sense by Thomas Paine; HTML format, indexed by section

- Rights of Man

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from May 2015

- Thomas Paine

- 1737 births

- 1809 deaths

- 18th-century American writers

- 18th-century English people

- 18th-century English writers

- 19th-century American writers

- 19th-century English people

- Age of Enlightenment

- Agrarian theorists

- American abolitionists

- American classical liberals

- American deists

- American foreign policy writers

- American libertarians

- American male writers

- American pamphlet writers

- American political philosophers

- American revolutionaries

- British classical liberals

- British people of the American Revolution

- British republicans

- Burials in New York

- Critics of religions

- Deist philosophers

- Deputies to the French National Convention

- English businesspeople

- English inventors

- English writers

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- History of New Rochelle, New York

- Kingdom of Great Britain emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Patriots in the American Revolution

- Pennsylvania political activists

- People educated at Thetford Grammar School

- People from Bordentown, New Jersey

- People from Greenwich Village

- People from New Rochelle, New York

- People from Thetford

- People of the American Enlightenment

- People of wars of independence of the Americas

- Political leaders of the American Revolution

- Prisoners sentenced to death by France

- Religious skeptics