Thonburi Kingdom

Thonburi Kingdom อาณาจักรธนบุรี Anachak Thonburi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1767–1782 | |||||||||

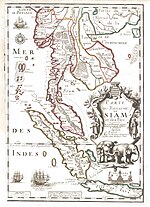

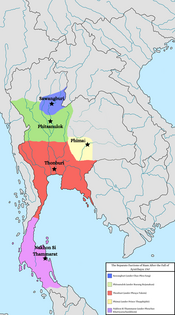

The sphere of influence of the Thonburi Kingdom following the vassalization of the Lao kingdoms in 1778. Early modern Southeast Asia political borders subject to speculation. | |||||||||

| Capital | Thonburi | ||||||||

| Common languages | Thai (official) Northern Thai Southern Thai Lao Khmer Shan Malay Various Chinese languages[1] | ||||||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1767–1782 | Taksin the Great | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

• Establishment | 28 December 1767 | ||||||||

• Capture of Nakhon Si Thammarat | 21 September 1769 | ||||||||

• Capture of Phitsanulok | 18 August 1770 | ||||||||

• Capture of Hà Tiên | 17 November 1771 | ||||||||

• Capture of Chiangmai | 14 January 1775 | ||||||||

• Fall of Phitsanulok | 15 March 1776 | ||||||||

• Capture of Vientiane | March 1779 | ||||||||

• Dissolution | 6 April 1782 | ||||||||

| Currency | Pod Duang | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

The Thonburi Kingdom (Thai: ธนบุรี) was a major Siamese kingdom which existed in Southeast Asia from 1767 to 1782, centered around the city of Thonburi, in Siam or present-day Thailand. The kingdom was founded by Taksin the Great, who reunited Siam following the collapse of the Ayutthaya Kingdom, which saw the country separate into five warring regional states. The Thonburi Kingdom oversaw the rapid reunification and reestablishment of Siam as a preeminient military power within mainland Southeast Asia, overseeing the country's expansion to its greatest territorial extent up to that point in its history, incorporating Lan Na, the Laotian kingdoms (Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Champasak), and Cambodia under the Siamese sphere of influence.[2]

The Thonburi Kingdom saw the consolidation and continued growth of Chinese trade from Qing China, a continuation from the late Ayutthaya period (1688-1767), and the increased influence of the Chinese community in Siam, with Taksin and later monarchs sharing close connections and close family ties with the Sino-Siamese community.

The Thonburi Kingdom lasted for only 14 years, ending in 1782 when Taksin was deposed by a major Thonburi military commander, Chao Phraya Chakri, who subsequently founded the Rattanakosin Kingdom, the fourth and present ruling kingdom of Thailand.

History

Taksin's Reunification of Siam

Phraya Tak, personal name Sin,[3] Zheng Zhao (鄭昭)[4] or Zheng Xin (鄭信), was a nobleman of Teochew Chinese descent.[5][6] By the time of Burmese Invasion of 1765-1767, Phraya Tak had been the governor of Tak and called to join the defense of Ayutthaya.[4] In January 1767, about three months before the Fall of Ayutthaya, Phraya Tak gathered his own forces of 500 followers[6] and broke through the Burmese encirclement to the east. After battling with Burmese scouting forces and some local resistances, Phraya Tak and his retinue settled in Rayong on the eastern Siamese coast.[7][8] There, Phraya Tak competed with Pu Lan the Phraya Chanthaburi or the governor of Chanthaburi for domination over the eastern coastline. In the famous episode, Phraya Tak ordered all cooking pots in the supplies to be destroyed and then successfully took Chanthaburi in June 1767. Phraya Tak established his dominions of influence on the eastern coast stretching from Bang Plasoi (Chonburi) to Trat.

Ayutthaya fell in April 1767. Due to the intervening Sino-Burmese War, Burma was obliged to divert most of its forces from Ayutthaya to the Chinese front.[3] The Burmese had left a garrison at Phosamton to the north of Ayutthaya under the command of the Mon Thugyi. The Burmese were in control only in Lower Central Siam as the rest of Siam fell into the hands of various warlord regimes that sprang up. In the northeast, Prince Kromma Muen Thepphipit established himself in Phimai.[9] To the north, Chaophraya Phitsanulok Rueang made his base in Phitsanulok, while the heterodox monk Chao Phra Fang[8][9] founded a theocratic regime in Sawangkhaburi. To the south, Phra Palat Nu or Chao Nakhon[8] became the leader of Nakhon Si Thammarat (Ligor) regime.[3]

In October 1767,[4][7] Phraya Tak left Chanthaburi and took his fleet of 5,000 men[6][10] to the Chao Phraya. He took Thonburi and proceeded to attack the Burmese at Phosamton[11] in November, defeating the Burmese commander Thugyi or Suki.[8] Phraya Tak founded the new Siamese capital at Thonburi and enthroned himself as king there in December 1767.[6] He is colloquially and posthumously known as King Taksin, combining his title Phraya Tak and his name Sin.[citation needed] For strategic reasons, Taksin decided to move the capital from Ayutthaya to Thonburi, making it easier for commerce.[6] Six months after the Fall of Ayutthaya, Taksin managed to reconquer and establish his powers in Central Siam. A Burmese force from Tavoy arrived to attack the Chinese encampment of Bangkung in Samut Songkhram. King Taksin repelled the Burmese in the Battle of Bangkung in 1768.[12]

King Taksin then went on his campaigns against other competing rival regimes to unify Siam.[7] He first moved against Phitsanulok in the north in 1768 but was defeated at Koeichai with Taksin himself got shot at his leg. Thonburi went on to conquer the Phimai regime in the northeast in 1768[7] and the Nakhon Si Thammarat regime in October 1769.[10] Prince Thepphiphit was executed[10] but Nakhon Nu of Ligor was allowed to live in custody. In the north, Chao Phra Fang conquered and incorporated the Phitsanulok regime in 1768,[8] becoming a formidable opponent of Taksin. In 1770, the forces of Chao Phra Fang penetrated south as far as Chainat. King Taksin, in retaliation, led the Thonburi armies to capture Phitsanulok in August 1770. Thonburi forces continued north to seize Sawangkhaburi. Chao Phra Fang escaped and disappeared from history. With the conquest of the last rival regime by 1770, Taksin's position as the ruler of Siam was assured[13] and Siam was unified at last.

Invasion of Cambodia and Hà Tiên

In the eighteenth century, the port city of Hà Tiên, ruled by the Cantonese Mạc Thiên Tứ, arose to become the economic center of the Gulf of Siam.[14] After the fall of Ayutthaya, two Ayutthayan princes: Prince Chao Sisang and Prince Chao Chui, took refuge at Oudong the royal city of Cambodia and Hà Tiên, respectively. The Qing Chinese court at Beijing refused to recognize King Taksin as the ruler of Siam in Chinese tributary system because Mạc Thiên Tứ had told Beijing that the remaining descendants of the Ayutthayan dynasty were with him in Hà Tiên.[15] In 1769, King Taksin urged the pro-Vietnamese King Ang Ton of Cambodia to send tributes to Siam. Ang Ton refused and Taksin sent armies to invade Cambodia in 1769 but did not meet with success.[16]

In 1771, Taksin resumed his campaigns to invade Cambodia and Hà Tiên in order to find the Ayutthayan princes and to put the pro-Siamese Ang Non on the Cambodian throne. King Taksin ordered Phraya Yommaraj Thongduang (later King Rama I) to bring the army of 10,000 men to invade Cambodia by land, while King Taksin himself with Phraya Phiphit Chen Lian (陳聯, called Trần Liên in Vietnamese sources)[14] as the admiral invaded Hà Tiên with the fleet of 15,000 men. Hà Tiên fell to Siamese invaders in November 1771. Phraya Yommaraj was also able to seize control of Oudong and Cambodia. Both Mạc Thiên Tứ and the Cambodian king Ang Ton fled to Cochinchina under the protection from the Nguyen Lord. Taksin appointed Chen Lian as the new governor of Hà Tiên with the title of Phraya Rachasetthi.[14] The Siamese armies continued in search for Mạc Thiên Tứ and Ang Ton but were defeated by Vietnamese forces at Châu Đốc.[14] Taksin put Ang Non in power in Cambodia with himself returning to Thonburi in December 1771, leaving Chen Lian in Hà Tiên and Phraya Yommaraj to be in charge in Cambodia.

Prince Chui was captured and brought to be executed at Thonburi,[14] while Prince Sisang died in 1772. The Nguyen Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần organized the Vietnamese counter-offensives[14] in order to restore Mạc Thiên Tứ and Ang Ton to their former positions. Chen Lian, the Siam-appointed governor of Hà Tiên, was defeated and left Hà Tiên for three days until he managed to raise a fleet to retake the city. The Vietnamese commander Nguyễn Cửu Đàm led the armies to seize control of Phnom Penh and Cambodia in July 1772,[14] prompting Ang Non to move to Kampot. However, this Siamese-Vietnamese War coincided with the uprising of the Tây Sơn, which began in 1771, against the Nguyen Lord's regime. Instability at home made the Nguyen Lord order Mạc Thiên Tứ to make peace with Siam in 1773. Taksin then realized that the Siamese control over Cambodia and Hà Tiên was untenable. He ordered the withdrawal of Siamese troops from Cambodia and Hà Tiên in 1773 but not before 10,000 Cambodians were taken as captives to Thonburi.[17]

Ang Ton resumed his rule in Cambodia. With the Vietnamese support dwindling due to the Tây Sơn uprising, however, Ang Ton decided to reconcile with his rival Ang Non and with Siam. Ang Ton abdicated in 1775 in favor of Ang Non, who became the new pro-Siamese King of Cambodia.[14] With the Ayutthayan princes gone, the Qing court had improved attitudes towards Taksin.The Qing finally recognized Taksin as Wang (王) or King[4] or the ruler of Siam in 1777 in the Chinese tributary system.

Expedition to Chiangmai

After the Burmese conquest of Lanna (modern Northern Thailand) in 1763, Lanna including Chiangmai returned to the Burmese rule. Thado Mindin the Burmese governor of Chiangmai oppressed[12][18] the local Lanna nobles. King Taksin marched against the Burmese-held Chiangmai in 1771 but failed to take the city. In Chiangmai, Thado Mindin faced opposition from Phaya Chaban Boonma,[18][19] the native Lanna noble who led the resistance against Burmese domination.

In 1772, King Hsinbyushin of the Burmese Konbaung dynasty realized that Siam had recovered and arose powerful under Thonburi regime. Hsinbyushin initiated a new campaign against Siam.[20] He ordered troops to be gathered in Burmese Chiangmai and the Mon town of Martaban in order to invade Siam from both the north and the west in two directions: a similar approach to the invasion of 1765-1767.[12] In 1774, Binnya Sein, a nephew of Binnya Dala the last king of Hanthawaddy, led a failed Mon rebellion against Burma, resulting in the mass exodus of thousands of Mon people into Siam. Hsinbyushin appointed Maha Thiha Thura, the renowned general from the Sino-Burmese War, to be the supreme commander of the new campaigns and assigned Nemyo Thihapate to be in charge of Burmese forces in Lanna.[21]

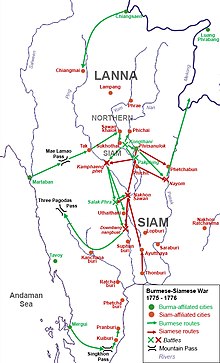

The Burmese forces from Chiangmai attacked the Northern Siamese border towns of Sawankhalok in 1771 and Phichai in 1772-1773.[12] Taksin was then resolved to extinguish Burmese threat from the north once and for all by conducting an expedition to seize the Burmese-held Chiangmai in December 1774. This expedition to the north coincided with the Mon refugee situation. Phaya Chaban of Chiangmai, upon learning of the Siamese invasion, joined with Kawila of Lampang to overthrow the Burmese. Phaya Chaban, under the guise of navigation, ran to submit to Taksin.[23] King Taksin marched to Tak where he received the Mon refugees. Taksin ordered Chaophraya Chakri to lead the vanguard to Lampang, where Kawila had earlier insurrected against the Burmese.[18] Kawila led the way for the Siamese armies to Chiangmai. The brothers Chaophraya Chakri and Surasi combined forces to successfully seize Chiangmai in January 1775.[19] Burmese leaders Thado Mindin and Nemyo Thihapate retreated to Chiangsaen where they reestablished Burmese administrative headquarter. This began the transfer of Lanna from Burmese rule to Siamese domination after 200 years of Lanna being under Burmese suzerainty,[19] even though northern parts of Lanna including Chiangsaen would remain under Burmese rule for another thirty years until 1804.

Phaya Chaban was rewarded with the governorship of Chiangmai whereas Kawila was made the governor of Lampang.[18][19] In 1777, the Burmese from Chiangsaen attacked Chiangmai in their bid to reclaim Lanna. Phaya Chaban decided to evacuate Chiangmai in the face of Burmese invasion due to numerical inferiority of his forces.[18] Chiangmai was then abandoned and ceased to exist as a functional city for twenty years until it was restored in 1797. Lampang under Kawila stood as the main frontline citadel against subsequent Burmese incursions.

Burmese Invasions

Plan of King Hsinbyushin to invade Siam from two directions was foiled by the Mon Rebelllion and the Siamese capture of Chiangmai.[12] Maha Thiha Thura, who had taken commanding position in Martaban, sent his vanguard force under Satpagyon Bo to invade Western Siam through the Three Pagodas Pass in February 1775. Taksin was unprepared as most of his troops were in the north defending Chiangmai. He recalled the northern Siamese troops down south to defend the west. Satpagyon Bo took Kanchanaburi and continued to Ratchaburi, where he encamped at Bangkaeo[12] (modern Tambon Nangkaeo, Photharam district), hence the name Bangkaeo Campaign. King Taksin sent preliminary forces under his son and his nephew to deal with the Burmese at Ratchaburi. The princes led the Siamese forces to completely encircle Satpagyon Bo at Bangkaeo in order to starve the Burmese into surrender.[12] Northern Siamese troops arrived in the battlefield of Bangkaeo, bringing the total number of Siamese to 20,000 men,[20] greatly outnumbering the Burmese. After 47 days of being encircled, Satpagyon Bo capitulated in March 1775. The Siamese took about 2,000[24] Burmese captives from this battle.

Six months after the Siamese victory at Bangkaeo, in September 1775, the Burmese from Chiangsaen attacked Chiangmai again. The two Chaophrayas Chakri and Surasi led troops north to defend Chiangmai.[12] However, Maha Thiha Thura took this opportunity to personally lead the Burmese armies of 35,000 men through the Mae Lamao Pass to invade Hua Mueang Nuea or Northern Siam[12] in October. Chakri and Surasi had to hurriedly return to defend Phitsanulok. Maha Thiha Thura laid siege on Phitsanulok, the administrative center of Northern Siam. King Taksin led the royal armies from Thonburi to the north and stationed at Pakphing near Phitsanulok in efforts to relieve the siege of the city. Maha Thiha Thura managed to attack the Siamese supply line[12] at Nakhon Sawan and Uthaithani. He also defeated King Taksin in the Battle of Pakphing in March 1776, compelling the Siamese king to retreat south to Phichit.[12] Chaophrayas Chakri and Surasi then decided to abandon and evacuate Phitsanulok. Phitsanulok fell to the Burmese, was completely destroyed and burnt to the grounds.

Maha Thiha Thura was preparing to march onto Thonburi when he learned of the death of the Burmese King Hsinbyushin in 1776.[12] Maha Thiha Thura was recalled,[21] decided to abruptly abandon the campaign in Siam and quickly return to Burma in order to support his son-in-law Singu Min to the Burmese throne. The remaining Burmese regiments in Siam were thus left disorganized and uncontrolled. Siam nearly succumbed to the Burmese conquest for the second time after the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767. The untimely demise of Hsinbyushin saved Siam from such fate. King Taksin took this chance to pursue the retreating Burmese.[12] The Burmese had all left Siam by September 1776 and the war came to the end.

Invasion of Laos

In 1765, Lao kingdoms of Luang Phrabang and Vientiane became Burmese vassals. After the Siamese capture of Chiangmai in 1775, the Burmese influence in Laos waned.[25] King Ong Boun of Vientiane had been a Burmese ally, as he instigated the Burmese to invade his rival Luang Phrabang two times in 1765 and 1771.[26] King Taksin had been suspicious about Ong Boun being in cooperation with Burma.[27] In 1777, the governor of Nangrong rebelled against Thonburi with support from Champasak. King Taksin ordered Chaophraya Chakri to lead the Siamese armies to invade and retaliate Champasak. After this expedition, Taksin rewarded Chakri with the rank and title of Somdet Chaophraya Maha Kasatsuk. The rank of Somdet Chaophraya was the highest possible a noble could attain with honors equal to a prince.[28]

In 1778, Phra Vo,[26] a Lao secessionist figure, sought protection under Siam against Ong Boun of Vientiane. However, Ong Boun managed to send troops to defeat and kill Phra Vo in the same year. This provoked Taksin who regarded Phra Vo as his subject. The death of Phra Vo at the hands of Vientiane served as the casus belli for Thonburi to initiate the subjugation of Lao kingdoms in 1778. He ordered Chaophraya Chakri to conduct the invasion of Laos. Chaophraya Chakri commanded his brother Chaophraya Surasi to go to Cambodia to raise troops there[29] and invade Laos from another direction. Surasi led his Cambodian army to cross the Liphi waterfall and capture Champasak including the king Sayakumane who was taken to Thonburi. Chakri and Surasi then converged on Vientiane. King Surinyavong of Luang Phrabang, who had long been holding grudges against Ong Boun,[26] joined the Siamese side and contributed forces. King Ong Boun assigned his son Nanthasen to lead the defense of Vientiane. Nanthasen managed to resist the Siamese for four months[25][26] until the situation became critical. Ong Boun secretly escaped Vientiane, leaving his son Nanthasen to surrender and open the city gates[26] to the Siamese in 1779.

Buddha images of Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang, the palladia of the Vientiane kingdom, were taken by the victorious Siamese to Thonburi to be placed at Wat Arun. Lao inhabitants of Vientiane, including members of royalty Nanthasen and the future king Anouvong, were deported to settle in Thonburi and various places in Central Siam.[30] All three Lao kingdoms of Luang Phrabang, Vientiane and Champasak became the tributary kingdoms of Siam on this occasion.[30]

Downfall of Thonburi regime

Despite Taksin's successes, by 1779, Taksin was showing signs of mental instability. He was recorded in the Rattanahosin's gazettes and missionaries's accounts as becoming maniacal, insulting senior Buddhist monks, proclaiming himself to be a sotapanna or divine figure. Foreign missionaries were also purged from times to times. His officials, mainly ethnic Chinese, were divided into factions, one of which still supported him but the other did not. The economy was also in turmoil, famine ravaged the land, corruption and abuses of office were rampant, the monarch attempted to restore order by harsh punishments leading to the execution of large numbers of officials and merchants, mostly ethnic Chinese which in turn led to growing discontent among officials.[citation needed] Siamese nobles were alienated by Taksin's unorthodox rule, such as the lack of recreating a "proper capital" at Thonburi, his personal style of leadership, as well as by his religious unorthodoxy.[31]

In 1782 Taksin sent a 20,000 man army to Cambodia, led by generals Phraya Chakri and Bunma, to install a pro-Siamese monarch upon the Cambodian throne following the death of the Cambodian monarch. While the army was en route to Cambodia, Taksin was overthrown in a rebellion that successfully seized the Siamese capital, which, depending on the sources, captured Taksin or allowed Taksin to peacefully step down from the throne and become a monk. Phraya Chakri, upon receiving news of the rebellion while on campaign, hurriedly marched his army back to Thonburi. The story behind Phraya Chakri's seizure of the Siamese throne is disputed: according to Wyatt, Phraya Chakri accepted the rebels' offer to give him the throne after Taksin was deposed by the rebels. According to Baker and Phongchaichit, Phraya Chakri, with his strong support from established nobles, staged a bloody coup d'teat upon arriving at the Siamese capital. What is supported by these sources however is that Taksin was executed shortly after Phraya Chakri's seizure of the capital.[32][33][34]

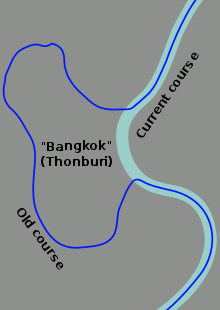

After securing the capital, Phraya Chakri took the throne as King Ramathibodi, posthumously known as Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke, today known as King Rama I, founding the House of Chakri, the present Thai ruling dynasty. After Taksin's death, Rama I moved his capital from Thonburi, across the Chao Phraya River, to the village of Bang-Koh (meaning "place of the island"), where he would construct his new capital. The new capital was established in 1782, called Rattanakosin, today now known as Bangkok.[citation needed]

The city of Thonburi remained an independent town and province until it was merged into Bangkok in 1971.

Government

Thonburi government organization was centered around a loose-knit organization of city-states, whose provincial lords were appointed through 'personal ties' to the king, similar to Ayutthaya and, later, Rattanakosin administrations.[35][36] Thonburi inherited most of the government apparatus from the Late Ayutthaya. Two Prime Ministers; Samuha Nayok the Prime Minister and Samuha Kalahom the Minister of Military, led the central government. In the early years of Thonburi, Chaophraya Chakri Mut the Muslim of Persian descent hold the position of Samuha Nayok until his death in 1774. Chakri Mut was succeeded as Prime Minister by Chaophraya Chakri Thongduang who later became King Rama I. Below the Prime Minister were the four ministers of Chatusadom.

Like in Ayutthaya, the regional government was organized in the hierarchy of cities, in which smaller towns were under jurisdiction of larger cities. The provincial government was a loose association of local lords tied by personal ties to the king.[10] The regional administrative center of Northern Siam was Phitsanulok, while for Southern Siam was Nakhon Si Thammarat. After his conquest of Hua Mueang Nuea or Northern Siam in 1770, King Taksin installed his early followers who had distinguished themselves in battles as the governors of Northern Siamese cities.[10] Governors of Sawankhalok, Nakhon Sawan and Sankhaburi were given exceptionally high rank of Chaophraya,[37] while the central Chatusadom ministers were ranked lower as Phraya. Chaophraya Surasi Boonma was the governor of Phitsanulok during Thonburi times. Phitsanulok and other Northern Siamese towns were devastated by Maha Thiha Thura's invasion in 1775–1776.

After his conquest of the Ligor regime in 1769, Taksin made his nephew Prince Nara Suriyawong the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat. Prince Nara Suriyawong of Ligor died in 1777 and King Taksin made Chaophraya Nakhon Nu, the former leader of the Ligor regime, an autonomous ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat. Ligor would enjoy autonomy until 1784 when King Rama I curbed the power of the Ligor by replacing Nakhon Nu with Nakhon Nu's son-in-law Nakhon Phat as the 'governor' of Ligor instead.[38]

With the exception of Bunma (later Chao Phraya Surisi and later Maha Sura Singhanat), a member of the old Ayutthaya artistocracy who had joined Taksin early on in his campaigns of reunification, and later Bunma's brother, Thongduang (later Chao Phraya Chakri and later King Rama I), high political positions and titles within the Thonburi Kingdom were mainly given to Taksin's early followers, instead of the already established Siamese nobility who survived after the fall of Ayutthaya, many of whom having supported Thep Phiphit, the governor of Phitsanulok and an Ayutthaya aristocrat, during the Siamese civil war. In the Northern cities, centered around Sukhothai and Phitsanulok, Taksin installed early supporters of his who had distinguished themselves in battle, many of whom were allowed to establish their own local dynasties afterwards, but elsewhere, several noble families had kept their titles and positions within the new kingdom (Nakhon Si Thammarat, Lan Na), (the ruler of Nakhon Si Thammarat that Taksin defeated during the civil war was reinstated as its ruler) whose personal connections made them a formidable force within the Thonburi court.[39][40]

Kingship

The Thonburi period saw the return of 'personal kingship', a style of ruling that was used by Naresuan but was abandoned by Naresuan's successors after his death. Taksin, similar to Naresuan, personally led armies into battle and often revealed himself to the common folk by partaking in public activities and traditional festivities, thereby abandoning the shroud of mysticism as adopted by many Ayutthaya monarchs. Also similar to Naresuan, Taksin was known for being a cruel and authoritarian monarch. Taksin reigned rather plainly, doing little to emphasize his new capital as the spiritual successor to Ayutthaya and adopted an existing wat besides his palace, Wat Jaeng (also spelled Wat Chaeng, later Wat Arun), as the principal temple of his kingdom. Taksin largely emphasized the building of moats and defensive walls in Thonburi, all while only building a modest Chinese-style residence and adding a pavilion to house the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang images at Wat Jaeng, recently taken in 1778 from the Lao states (Vientiane and Luang Prabang, respectively).[41]

Territories

After the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, the Siamese mandala system was left in disarray and its former tributary states faced political uncertainties.[42] The Malay sultanates that used to pay bunga mas tributes to Ayutthaya initially nullified their tributary ties[38] and refused any further allegiance.[42] After the establishment of Thonburi and the momentous rebirth of Siam, the sultanates of Pattani, Terengganu and possibly Kedah sent tributes to Thonburi in 1769.[42] Francis Light mentioned that Kedah had sent tributes to Siam[42] but did not specify a year. Despite the bunga mas tributes, the degree of actual Siamese control over the Malay sultanates in the Thonburi Period was doubtful. King Taksin requested military and monetary obligations from Pattani, Kelantan and Terengganu to aid Siam against the Burmese invasion in 1776. However, the Malay sultans ignored this order and did not face any repercussions.[42] In 1777, Nakhon Nu the ruler of Ligor proposed to King Taksin to send expedition to subjugate the Malay sultanates. King Taksin refused, however, stating that the defense of frontiers against Burmese incursions was more of priority. Siam only resumed real political control over the Northern Malay sultanates in 1786 in the Rattanakosin Period.

With the exception of the western Tenasserim Coast, the Thonburi Kingdom reconquered most of the land previously held under the Ayutthaya Kingdom[43] and expanded Siam to its greatest territorial extent up to that point. During the Thonburi period, Siam acquired new Prathetsarats or tributary kingdoms. Thonburi took control of Lanna in 1775, ending the 200 years of Burmese vassalage, which became Northern Thailand today. Taksin appointed his supporters against the Burmese, Phaya Chaban and Kawila, as the governors of Chiangmai and Lampang respectively in 1775. The princedom of Nan also came under the power of Thonburi in 1775. However, Burma pushed on an intensive campaign to reclaim lost Lanna territories, resulting in the abandonment of Chiangmai in 1777 and Nan in 1775 due to Burmese threats. Only Lampang under Kawila stood as the forefront citadel against Burmese incursions.

After the capture of Vientiane in 1779, all of the three Lao kingdoms of Luang Phrabang, Vientiane and Champasak became tributary kingdoms under Siamese suzerainty.[30] King Taksin appointed the Lao prince Nanthasen as the new King of Vientiane in 1781.[44] Vassal (mandala) states of the Thonburi Kingdom at its height in 1782, to varying degrees of autonomy, included the Nakhon Si Thammarat Kingdom, the Northern Thai principalities of Chiang Mai, Lampang, Nan, Lamphun, and Phrae, and the Lao Kingdoms of Champasak, Luang Prabang, and Vientiane.

Economy

In the Late Ayutthaya Period, Siam was a prominent rice exporter to Qing China.[10][45][46] After the Fall of Ayutthaya in 1767, the Siamese economy totally collapsed. Rice production and economic activities ceased. Thonburi period was the time of economic crisis as people died from warfare and starvation and inflation was prevalent. Siam became a rice importer. In 1767, after his reconquest of Ayutthaya, King Taksin donated to over 10,000 desolate people.[4] He also ordered an Ayutthayan bronze cannon to be broken down into pieces to buy rice and distribute to the starving populace, earning him a great popularity. The rice price in Thonburi period was high. The port city-state of Hà Tiên was the major rice importer into Siam before 1771. Given the frequency of war in the Thonburi period, the Siamese royal court spent its revenue on warfare and reconstruction.

Qing China and the Dutch were main trading partners of Siam in the Late Ayutthaya Period. The Ayutthayan court relied on trade with China under the Chinese tributary system as a source of revenue. The Dutch had earlier abandoned their factory in Ayutthaya and left Siam in 1765 due to the Burmese invasion.[47] The Thonburi court sent a letter to the Supreme Government of Dutch East Indies Company at Batavia in 1769 in efforts to resume the trade but the Dutch were not interested.[48] In order to generate a reliable court income, King Taksin, himself a Teochew Chinese, had to put Siam under the Chinese tributary system by gaining imperial recognition from Beijing. However, the Qing court under Emperor Qianlong refused to accept Taksin as the rightful ruler of Siam because Mạc Thiên Tứ the ruler of Hà Tiên had told Beijing that the remaining descendants of the fallen Ayutthayan dynasty were with him in Hà Tiên.[15][14] This urged Taksin to conduct an expedition in 1771 to destroy Hà Tiên and to capture the scions of the former dynasty. Only then the Qing finally recognized Taksin as the King of Siam in the Chinese tributary system in 1777.[15]

Even though Siam did not procure successful relation with China until 1777, trade in private sectors flourished. A Chinese document from 1776 suggested a rapid revival of Sino-Siamese trade after the Burmese war.[45] King Taksin employed his own personal Chinese merchants to trade at Guangzhou to acquire wealth into the royal revenue. Prominent royal merchants of King Taksin included Phra Aphaiwanit Ong Mua-seng[49] (王満盛, a grandson of Ong Heng-Chuan 王興全 the Hokkien Chinese Phrakhlang of the Late Ayutthaya) and Phra Wisetwari Lin Ngou[49] (林伍). J. G. Koenig, the Danish botanist who visited Siam in 1779, observed that Siam "was amply provided with all sorts of articles from China." and that King Taksin made fortunes out of "buying the best goods imported at a very low price and selling them again to the merchants of the town at 100 percent interest.".[4]

During the early years of Thonburi, a Teochew Chinese Phraya Phiphit Chen Lian was the acting Phrakhlang[9] or the Minister of Trade. Chen Lian was appointed as the governor of Hà Tiên in 1771 and was succeeded as Phrakhlang by another Chinese Phraya Phichai Aisawan Yang Jinzong[9] (楊進宗), who would remain in position until his death in 1777.

Siamese economic conditions improved over time as trade and production resumed. After the devastation of Central Siam by the Burmese invasion of 1775–1776, however, Siam was again plunged into another economic downturn. King Taksin ordered his high-ranking ministers to supervise the rice production in the outskirts of Thonburi and had to postpone tributary mission to China.[15] During the Burmese Invasion of Ayutthaya, the elites of Ayutthaya found no way to protect their wealth and belongings other than by simply burying them in the grounds. However, not all of them returned to claim their wealth as they either died or were deported to Burma. Surviving owners and other hunters rushed to dig for treasures in the grounds of the former royal city. This Ayutthaya treasure rush was so widespread and lucrative that the Thonburi court intervened to tax.

Demography and Society

Much of the western provinces of Siam were depopulated for several decades until the early 19th century due to the near-constant state of fighting with Burma.[50]

The years of warfare and the Burmese invasions prevented any peasants to engage in agricultural activities. The Siamese war captives who had been taken to Burma following the fall of Ayutthaya in 1767 and the general lack of manpower were the source of the problems. Taksin had tried his best to encourage people to come out of forest hidings, of whom had fled into the countryside prior to and during the 1765-67 Burmese invasion, and to promote farming. He promulgated the Conscription Tattooing in 1773, which left a permanent mark on commoners' bodies, preventing them from fleeing or moving. The practice continued well into the Rattanakosin period until the abolition of levy during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). As Taksin was from a Chinese merchant family, he sold both his royal and familial properties and belongings to subsidize production by giving money off to people. This proved to be a temporary relief for such an economic decline. Nevertheless, the Siamese economy after the wars needed time to rehabilitate. Thonburi began forming its society.

Taksin gathered resources through wars with neighboring kingdoms and deals with Chinese merchants. Major groups of people in Thonburi were local Thais, phrai, or 'commoners', Chinese, Laotians, Khmers, and Mons. Some powerful Chinese merchants trading in the new capital were granted officials titles. After the king and his relatives, officials were powerful. They held numbers of phrai, commoners who were recruited as forces. Officials in Thonburi mainly dealt with military as well as 'business' affairs.

Military

Much like Naresuan two centuries prior, Taksin often personally led his troops on campaign and into battle. Later on, Taksin would increasingly delegate his chief generals, Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi, on leading Thonburi military expeditions, such as the 1781 expedition to Cambodia, immediately prior to Taksin's deposition.[51]

Following the Burmese–Siamese War (1775–1776), the military balance of power within the kingdom shifted as Taksin took away troops from his old followers in the Northern Cities, who had performed disappointingly in the previous war, and concentrated these forces to protect the capital at Thonburi, similar to what Naresuan did, placing more military power within the hands of two powerful brother-generals from the traditional aristocracy, Chao Phraya Chakri and Chao Phraya Surasi.[52]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

Diplomacy

Taksin himself also commissioned trade missions to neighbouring and foreign countries to bring Siam back to outside world, the Qing dynasty being at the forefront of these missions. He dispatched several tributary missions to the Qing in 1781 to resume diplomatic and commercial relationships between the two countries which had stretched back, beginning in the Sukhothai period and had expanded significantly during the late Ayutthaya period.[53]

In August 1768,[54] Taksin sent a tributary mission to Qing China to require the royal seal, claiming that the throne of Ayutthaya Kingdom had come to an end. However, for a long time, the Qing Court refused to recognize Taksin as a legitimate ruler, citing the presence of then still-powerful claimants to the Siamese throne. Eventually, the Qing Court approved the royal status of Taksin as the new King of Siam. However, the letter of recognition from China only arrived after the death of King Taksin.[55]

In 1776, Francis Light of the Kingdom of Great Britain sent 1,400 flintlocks along with other goods as gifts to Taksin. Later, Thonburi ordered some guns from England. Royal letters were exchanged and in 1777, George Stratton, the Viceroy of Madras, sent a gold scabbard decorated with gems to Taksin.[clarification needed]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

See also

- King Taksin the Great

- Coronation of the Thai monarch

- List of Kings of Thailand

- Thonburi province

- Thon Buri (district)

References

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 122. ISBN 974957544X. "Within a decade or so, a new Siam already had succeeded where Naresuan and his Ayutthaya predecessors had failed in creating a new Siamese empire encompassing Lan Na, much of Lan Sang [sic], as well as Cambodia, and large portions of the Malay Peninsula."

- ^ a b c Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand: A Short History. Silkworm Books.

- ^ a b c d e f Wade, Geoff (19 December 2018). China and Southeast Asia: Historical Interactions. Routledge.

- ^ Baker, Chris (30 May 2014). A History of Thailand. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e Rappa, Antonio L. (21 April 2017). The King and the Making of Modern Thailand. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d Smith, Robert (7 July 2017). The Kings of Ayutthaya: A Creative Retelling of Siamese History. Silkworm Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e Mishra, Patit Paban (2010). The History of Thailand. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ a b c d Wang, Gungwu (2004). Maritime China in Transition 1750-1850. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ a b c d e f Baker, Chris (11 May 2017). A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "King Taksin". พระราชวังเดิม.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Damrong Rajanubhab, Prince (1918). พงษาวดารเรื่องเรารบพม่า ครั้งกรุงธน ฯ แลกรุงเทพ ฯ. Bangkok.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (19 February 2015). A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Breazeale, Kennon (1999). From Japan to Arabia; Ayutthaya's Maritime Relations with Asia. Bangkok: Foundation for the promotion of Social Sciences and Humanities Textbook Project.

- ^ a b c d Erika, Masuda (2007). "The Fall of Ayutthaya and Siam's Disrupted Order of Tribute to China (1767-1782)". Taiwan Journal of Southeast Asian Studies.

- ^ Rungswasdisab, Puangthong (1995). "War and Trade: Siamese Interventions in Cambodia; 1767-1851". University of Wollogong Thesis Collection.

- ^ Jacobsen, Trudy (2008). Lost Goddesses: The Denial of Female Power in Cambodian History. NIAS Press.

- ^ a b c d e Ongsakul, Sarasawadee (2005). History of Lan Na. Silkworm Books.

- ^ a b c d Penth, Hans (1 January 2001). A Brief History of Lanna: Northern Thailand from Past to Present. Silkworm Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Phraison Salarak (Thien Subindu), Luang (1919). Intercourse between Burma and Siam as recorded in Hmannan Yazawindawgyi. Bangkok.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Phayre, Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma: Including Burma Proper, Pegu, Taungu, Tenasserim, and Arakan, from the Earliest Time to the First War with British India. Trubner & Company.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (Ch. III). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Prachakitkarachak, Phraya (1908). Ruang phongsawadan Yonok.

- ^ Wade, Geoff (17 October 2014). Asian Expansions: The Historical Experiences of Polity Expansion in Asia. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Wyatt, David (September 1963). "Siam and Laos, 1767-1827". Journal of Southeast Asian History.

- ^ a b c d e Simms, Peter (2001). The Kingdoms of Laos: Six Hundred Years of History. Psychology Press.

- ^ Askew, Marc (7 December 2006). Vientiane: Transformations of a Lao Landscape. Routledge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Rabibhadana, Akin, M.R. (1996). The Organization of Thai Society in the Early Bangkok Period, 1782-1873. Wisdom of the Land Foundation & Thai Association of Qualitative Researchers.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rungswasdisab, Puangthong (1995). "War and Trade: Siamese Interventions in Cambodia; 1767-1851". University of Wollogong Thesis Collection.

- ^ a b c Van Roy, Edward (2009). "Under Duress: Lao war captives at Bangkok in the nineteenth century". Journal of the Siam Society. 97.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 267-268. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. p. 128. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 267-268. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Thailand Third Edition (p. 26). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 265. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Eoseewong, Nidhi (2007). การเมืองไทยสมัยพระเจ้ากรุงธนบุรี. Bangkok: Matichon.

- ^ a b Bisalputra, Pimpraphai; Sng, Jeffery (2020). "The Hokkien Rayas of Songkhla". Journal of the Siam Society. 108.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 265, 267. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (2003). Thailand : A Short History (2nd ed.). Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. pp. 125–26, 27–28. ISBN 974957544X.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya (p. 263, 264). Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ a b c d e Bradley, Francis R. (2015). Forging Islamic Power and Place: The Legacy of Shaykh Daud bin ‘Abd Allah al-Fatani in Mecca and Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press.

- ^ Wood, W.A.R. (1924). A History of Siam. London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd. p. 272. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Wyatt, David (September 1963). "Siam and Laos, 1767-1827". Journal of Southeast Asian History. 4 (2): 19–47. doi:10.1017/S0217781100002787.

- ^ a b Willis, Jr., John E. (2012). "Functional, Not Fossilized: Qing Tribute Relations with Đại Việt (Vietnam) and Siam (Thailand), 1700-1820". T'oung Pao – via Brill.

- ^ Zheng Yangwen (2011). China on the Sea: How the Maritime World Shaped Modern China. BRILL.

- ^ Ruangsilp, Bhawan (2007). Dutch East India Company Merchants at the Court of Ayutthaya: Dutch Perceptions of the Thai Kingdom, Ca. 1604-1765. BRILL.

- ^ The Diplomatic Correspondence between The Kingdom of Siam and The Castle of Batavia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia (ANRI). October 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Nibhatsukit, Warangkana (20 November 2019). "บทบาทของชาวจีนทางด้านเศรษฐกิจไทย จากสมัยอยุธยาจนถึงสมัยรัชกาลที่ 5". Journal of the Faculty of Arts, Silpakorn University.

- ^ "Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, "A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in…". New Books Network.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk. A History of Ayutthaya, p. 266. Cambridge University Press. (Kindle Edition.)

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64113-2.

- ^ "2017 07 13 Ayutthaya and Writing Thai History Today". Youtube. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

1:51:41-1:51:57

- Thonburi Kingdom

- Former countries in Thai history

- Former countries in Burmese history

- Former countries in Malaysian history

- Former monarchies of Southeast Asia

- Former kingdoms

- Indianized kingdoms

- 1760s in Thailand

- 1770s in Thailand

- 1780s in Siam

- 18th century in Burma

- 18th century in Siam

- States and territories established in 1767

- States and territories established in 1782

- 1767 in Thailand

- 1767 establishments by country

- 1767 establishments in Asia

- 1782 disestablishments in Asia

- 1760s establishments in Thailand

- 1780s disestablishments in Siam