Venice, Los Angeles

Venice | |

|---|---|

Venice Beach and Boardwalk | |

Venice neighborhood as delineated by the Los Angeles Times | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | County of Los Angeles |

| City | City of Los Angeles |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Mike Bonin (D) |

| • State Assembly | Betsy Butler (D) |

| • U.S. House | Ted Lieu (D) |

| • Neighborhood Council | Venice Neighborhood Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.1 sq mi (8 km2) |

| Population (2008)[1] | |

| • Total | 40,885 |

| • Density | 12,324/sq mi (4,758/km2) |

| Population changes significantly depending on areas included and recent growth. | |

| ZIP Code | 90291 |

| Area code(s) | 310, 424 |

Venice is a residential, commercial and recreational beachfront neighborhood on the Westside of the city of Los Angeles.

Venice was founded in 1905 as a seaside resort town. It was an independent city until 1926, when it merged with Los Angeles. Today, Venice is known for its canals, beaches, and the circus-like Ocean Front Walk, a two-and-a-half-mile pedestrian-only promenade that features performers, mystics, artists and vendors.

History

19th century

In 1839, a region called La Ballona that included the southern parts of Venice, was granted by the Mexican government to Machados and Talamantes, giving them title to Rancho La Ballona[2][3][4] Later this became part of Port Ballona.

Founding

Venice, originally called "Venice of America," was founded by tobacco millionaire Abbot Kinney in 1905 as a beach resort town, 14 miles (23 km) west of Los Angeles. He and his partner Francis Ryan had bought two miles (3.24 km) of oceanfront property south of Santa Monica in 1891. They built a resort town on the north end of the property, called Ocean Park, which was soon annexed to Santa Monica. After Ryan died, Kinney and his new partners continued building south of Navy Street. After the partnership dissolved in 1904, Kinney, who had won the marshy land on the south end of the property in a coin flip with his former partners, began to build a seaside resort like the namesake Italian city took it.[5]: 8

When Venice of America opened on July 4, 1905, Kinney had dug several miles of canals to drain the marshes for his residential area, built a 1,200-foot (370 m)-long pleasure pier with an auditorium, ship restaurant, and dance hall, constructed a hot salt-water plunge, and built a block-long arcaded business street with Venetian architecture. Tourists, mostly arriving on the "Red Cars" of the Pacific Electric Railway from Los Angeles and Santa Monica, then rode the Venice Miniature Railway and gondolas to tour the town. But the biggest attraction was Venice's mile-long gently sloping beach. Cottages and housekeeping tents were available for rent.

The population (3,119 residents in 1910) soon exceeded 10,000; the town drew 50,000 to 150,000 tourists on weekends.

Amusement pier

Attractions on the Kinney Pier became more amusement-oriented by 1910, when a Venice Miniature Railway, Aquarium, Virginia Reel, Whip, Racing Derby, and other rides and game booths were added. Since the business district was allotted only three one-block-long streets, and the City Hall was more than a mile away, other competing business districts developed. Unfortunately, this created a fractious political climate. Kinney, however, governed with an iron hand and kept things in check. When he died in November 1920, Venice became harder to govern. With the amusement pier burning six weeks later in December 1920, and Prohibition (which had begun the previous January), the town's tax revenue was severely affected.

The Kinney family rebuilt their amusement pier quickly to compete with Ocean Park's Pickering Pleasure Pier and the new Sunset Pier. When it opened it had two roller coasters, a new Racing Derby, a Noah's Ark, a Mill Chutes, and many other rides. By 1925 with the addition of a third coaster, a tall Dragon Slide, Fun House, and Flying Circus aerial ride, it was the finest amusement pier on the West Coast. Several hundred thousand tourists visited on weekends. In 1923 Charles Lick built the Lick Pier at Navy Street in Venice, adjacent to the Ocean Park Pier at Pier Avenue in Ocean Park. Another pier was planned for Venice in 1925 at Leona Street (now Washington Street).

For the amusement of the public, Kinney hired aviators to do aerial stunts over the beach. One of them, movie aviator and Venice airport owner B. H. DeLay, implemented the first lighted airport in the United States on DeLay Field (previously known as Ince Field). He also initiated the first aerial police in the nation, after a marine rescue attempt was thwarted. DeLay also performed many of the world's first aerial stunts for motion pictures in Venice.

Politics

By 1925, Venice's politics had become unmanageable. Its roads, water and sewage systems badly needed repair and expansion to keep up with its growing population. When it was proposed that Venice be annexed to Los Angeles, the board of trustees voted to hold an election. Annexation was approved in the election in November 1925, and Venice was formally annexed to Los Angeles in 1926.[5]: 8

Los Angeles had annexed the Disneyland of its day and proceeded to remake Venice in its own image. It was felt that the town needed more streets—not canals—and most of them were paved in 1929 after a three-year court battle led by canal residents. They wanted to close Venice's three amusement piers but had to wait until the first of the tidelands leases expired in 1946.

Oil

In 1929, oil was discovered south of Washington Street on the Venice Peninsula. Within two years, 450 oil wells covered the area, and drilling waste clogged the remaining waterways. It was a short-lived boom that provided needed income to the community, which suffered during the Great Depression. The wells produced oil into the 1970s.

Neglect

Los Angeles had neglected Venice so long that, by the 1950s, it had become the "Slum by the Sea." With the exception of new police and fire stations in 1930, the city spent little on improvements after annexation. The city did not pave Trolleyway (Pacific Avenue) until 1954 when county and state funds became available. Low rents for run-down bungalows attracted predominantly European immigrants (including a substantial number of Holocaust survivors) and young counterculture artists, poets, and writers. The Beat Generation hung out at the Gas House on Ocean Front Walk and at Venice West Cafe on Dudley. Police raids were frequent during that era.[6]

Gang activity

The Venice Shoreline Crips and the Latino Venice 13 (V-13) are the two main gangs active in Venice. V13 dates back to the 1950s, while the Shoreline Crips were founded in the early 1970s, making them one of the first Crip sets in Los Angeles.[citation needed] In the early 1990s V-13 and the Shoreline Crips were involved in a bloody, brutal war over crack cocaine sales territories.[7]

While violence has decreased, gangs continue to remain active in Venice. By 2002, numbers of gang members in Venice were reduced due to gentrification and increased police presence. According to a Los Angeles City Beat article, by 2003, many Los Angeles Westside gang members resettled in the city of Inglewood.[8] Author John Brodie challenges the idea of gentrification causing change and commented "... the gunplay of the Shoreline Crips and the V-13 is as much a part of life in Venice as pit bulls playing with blonde Labs at the local dog park."[9]

Population

The 2000 U.S. census counted 37,705 residents in the 3.17-square-mile Venice neighborhood—an average of 11,891 people per square mile, about the norm for Los Angeles; in 2008, the city estimated that the population had increased to 40,885. The median age for residents was 35, considered the average for Los Angeles; the percentages of residents aged 19 through 49 were among the county's highest.[10]

The neighborhood was moderately diverse ethnically, but had a high percentage of white people. The breakdown was whites, 64.2%; Latinos, 21.7%; blacks, 5.4%; Asians, 4.1%, and others, 4.6%. Mexico (38.4%) and the United Kingdom (8.5%) were the most common places of birth for the 22.3% of the residents who were born abroad—considered a low figure for Los Angeles.[10]

The median yearly household income in 2008 dollars was $67,647, a high figure for Los Angeles. The percentage of households earning $125,000 was considered high for the city. The average household size of 1.9 people was low for both the city and the county. Renters occupied 68.8% of the housing stock and house- or apartment owners held 31.2%.[10] Property values have been increasing lately due to the presence of technology companies such as Google Inc. (which in 2011 began leasing 100,000 square feet of space in Venice) and Snapchat (which leases property on Market Street and Abbot Kinney).[11]

The percentages of never-married men (51.3%), never-married women (40.6%), divorced men (11.3%) and divorced women (15.9%) were among the county's highest. The percentage of veterans who had served during the Vietnam War was among the county's highest.[10]

Geography

Description

According to the Mapping L.A. project of the Los Angeles Times, Venice is adjoined on the northwest by Santa Monica, on the northeast by Mar Vista, on the southeast by Culver City, Del Rey and Marina Del Rey, on the south by Ballona Creek and on the west by the Pacific Ocean.[12]

Venice is bounded on the northwest by the Santa Monica city line. The northern apex of the Venice neighborhood is at Walgrove Avenue and Rose Avenue abutting the Santa Monica Airport. On the east the boundary runs north-south on Walgrove Avenue to the neighborhood's eastern apex at Zanja Street, thus including the Penmar Golf Course but excluding Venice High School. The boundary runs on Lincoln Boulevard to Admiralty Way, excluding all of Marina del Rey, south to Ballona Creek.[10][13]

The City of Los Angeles official zoning map ZIMAS shows Venice High School as included in Venice,[14] as does Google Maps.[15]

Attractions and neighborhoods

Venice Canal Historic District

-

A canal

-

Another canal

-

Promotional flyer c. 1920

Abbot Kinney Boulevard

Abbott Kinney Boulevard is a principal attraction, with stores, restaurants, bars and art galleries lining the street. The street was described as "a derelict strip of rundown beach cottages and empty brick industrial buildings called West Washington Boulevard,"[16] and in the late 1980s community groups and property owners pushed for renaming a portion of the street to honor Abbot Kinney.[17][18] The renaming was widely considered as a marketing strategy to commercialize the area and bring new high-end businesses to the area.[19][20]

Venice Farmers Market

Founded in 1987, the Farmers Market operates every Friday from 7 to 11 a.m. on Venice Boulevard at Venice Way.

72 Market Street Oyster Bar and Grill

72 Market Street Oyster Bar and Grill was one of several historical footnotes associated with Market Street in Venice, one of the first streets designated for commerce when the city was founded in 1905. During the depression era, Upton Sinclair had an office there when he was running for governor, and the same historic building where the restaurant was located was also the site of the first Ace/Venice Gallery in the early 1970s[21] and, before that, the studio of American installation artist Robert Irwin.

Historic Post office

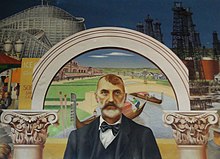

The Venice Post Office, a red-tile-roofed 1939 Works Progress Administration building designed by Louis A. Simon[22] on Windward Circle, featured one of two remaining murals painted in 1941 by Modernist artist Edward Biberman. Developer Abbot Kinney is in the center[23] surrounded by beachgoers in old-fashioned bathing suits, men in overalls, and a wooden roller coaster representing the Venice Pier on one side with contrasting industrial oil derricks that were once ubiquitous in the area on the other side.[24] Senior curator of American Art at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Ilene Susan Fort, said this is one of the better New Deal murals both artistically and historically. Although it contains brightly colored elements with amusing details, the intrusion of the ominous oil rigs and wells was very relevant at the time.[25] After the post office closed in 2012, movie producer Joel Silver unveiled plans for revamping the building as the new headquarters of his company, Silver Pictures.[26] The sale included a stipulation that he, or any future owner, preserve the New Deal-era murals and allow public access.[27] Restoration of the nearly pristine mural took over a year and cost about $100,000. LACMA highlighted the mural with an exhibit that displayed additional Biberman artworks, rare historical documents and Venice ephemera with the restored mural. Silver has a long-term lease on the mural that is still owned by the US Postal Service.[25] As of June 2016, the building remains under halted construction, with completion subject to resolution of multiple property liens. The mural's whereabouts are unknown,[28] putting the lessee in violation of the lease agreement's public access requirement.

Residences and streets

Many of Venice's houses have their principal entries from pedestrian-only streets and have house numbers on these footpaths. (Automobile access is by alleys in the rear.) The inland walk streets are made up primarily of around 620 single-family homes.[29] Like much of the rest of Los Angeles, however, Venice is known for traffic congestion. It lies 2 miles (3.2 km) away from the nearest freeway, and its unusually dense network of narrow streets was not planned for modern traffic. Mindful of the tourist nature of much of the district's vehicle traffic, its residents have successfully fought numerous attempts to extend the Marina Freeway (SR 90) into southern Venice.

Venice Beach

Venice Beach, which receives millions of visitors a year, has been labeled as "a cultural hub known for its eccentricities" as well as a "global tourist destination."[30][31] It includes the promenade that runs parallel to the beach (also the "Ocean Front Walk" or just "the boardwalk"), Muscle Beach, the handball courts, the paddle tennis courts, Skate Dancing plaza, the numerous beach volleyball courts, the bike trail and the businesses on Ocean Front Walk.

The basketball courts in Venice are renowned across the country for their high level of streetball; numerous professional basketball players developed their games or have been recruited on these courts.[32]

Many Zapotec-speaking people from the town of Tlacolula de Matamoros, Mexico work in stalls along the boardwalk.[33]

Fishing pier

Along the southern portion of the beach, at the end of Washington Boulevard, is the 'Venice Fishing Pier'. A 1,310-foot (400 m) concrete structure, it first opened in 1964, was closed in 1983 due to El Niño storm damage, and re-opened in the mid-1990s. On December 21, 2005, the pier again suffered damage when waves from a large northern swell caused part of it to fall into the ocean.

The pier remained closed until May 25, 2006, when it was re-opened after an engineering study concluded that it was structurally sound.

Breakwater

The Venice Breakwater is an acclaimed local surf spot in Venice. It is located north of the Venice Pier and lifeguard headquarters and south of the Santa Monica Pier. This spot is sheltered on the north by an artificial barrier, the breakwater, consisting of an extending sand bar, piping, and large rocks at its end.

In late 2010, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors conducted a $1.6 million replacement of 30,000 cubic yards of sand at Venice Beach eroded by rainstorms in recent years. Although Venice Beach is located in the city of Los Angeles, the county is responsible for maintaining the beach under an agreement reached between the two governments in 1975.[34]

Oakwood

The Oakwood portion of Venice, also known as "Ghost Town" and the "Oakwood Pentagon," lies inland from the tourist areas and is one of the few historically African American areas in West Los Angeles; Latinos now constitute the overwhelming majority of the residents. During the age of restrictive covenants that enforced racial segregation, Oakwood was set aside as a settlement area for Black-Americans, who came by the hundreds to Venice to work in the oil fields during the 1930s and 1940s. After the construction of the San Diego Freeway, which passed through predominantly Mexican American and immigrant communities, those groups moved further west and into Oakwood where black residents were already established. White-Americans moved into Oakwood during the 1980s and 1990s and Latinos moved out.[35]

By the end of the 20th century, gentrification had altered Oakwood. Although still a primarily Latino and African-American neighborhood, the neighborhood is in flux. According to Los Angeles City Beat,[36] "In Venice, the transformation is... obvious. Homes are fetching sometimes more than $1 million, and homies are being displaced every day." In 2012, an article in the Los Angeles Times predicted that the wine shops, cafes, restaurants and other businesses opening on Rose Avenue—adjacent to Oakwood—would soon lead to the other streets of Venice being transformed into upmarket areas.[35] Xinachtli, a Latino student group from Venice High School and subset of MEChA, refers to Oakwood as one of the last beachside communities of color in California. Chicanos, Hispanics, and Latinos of any race or ethnicity make up over 50% of Venice High School's student body.[37]

East Venice

East Venice is a racially and ethnically mixed residential neighborhood of Venice that is separated from Oakwood and Milwood (the area south of Oakwood) by Lincoln Boulevard, extending east to the border with the Mar Vista neighborhood, near Venice High School and Santa Monica Municipal Airport. Aside from the commercial strip on Lincoln (including the Venice Boys and Girls Club and the Venice United Methodist Church), the area almost entirely consists of small homes and apartments as well as Penmar Park and (bordering Santa Monica) Penmar Golf Course. The existing population (primarily composed of Caucasians, Hispanics/Latinos, and Asians, with small numbers of other groups) is being supplemented by new arrivals who have moved in with gentrification.

A housing project, Lincoln Place Apartment Homes, built by the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles is currently undergoing a $140 million renovation to add 99 new market-rate apartment homes and to update the remaining 696 existing homes. A new pool, two-story fitness center, resident park and sustainable landscaping are being added.[38] Aimco, which acquired the property in 2003, had previously been in a legal battle to determine whether or not Lincoln Place could be demolished and rebuilt. In 2010, Aimco settled with tenants and agreed to reopen the project and return scores of evicted residents to their homes and add hundreds of units to the Venice area.[39]

Creative works

Venice is known as a hangout for the creative and the artistic.[40] In the 1950s and 1960s, Venice became a center for the Beat generation. There was an explosion of poetry and art. Major participants included Stuart Perkoff, John Thomas, Frank T. Rios, Tony Scibella, Lawrence Lipton, John Haag, Saul White, Robert Farrington, Philomene Long, and Tom Sewell.[6]

Other notable Venice Poets [41] 20th and 21st Century: Millicent Borges Accardi, Linda Albertano, Richard Beban, Molly Bendall, Terry Blackhawk, Kate Braverman, Susie Bright, Derrick Brown, Charles Bukowski, Luis Campos, Exene Cervenka, Neeli Cherkovski, Jeanette Clough, Wanda Coleman, Catherine Daly, Fred Dewey, Robert Duncan, Bob Flanagan, Amy Gerstler, S.A. Griffin, Bob Kaufman, Gluefish Lou, Bill Margolis, Ellyn Maybe, Rod McKuen, Viggo Mortensen, Holly Prado, Jack Skelley, Patti Smith, Arnold Springer, David St. John, Amber Tamblyn, Elizabeth Treadwell, David Trinidad, Tom Waits.

Architecture

Designers Charles and Ray Eames had their offices at the Bay Cities Garage on Abbot Kinney Boulevard from 1943 on, when it was still part of Washington Boulevard; Eames products were also manufactured there until the 1950s.[42] The brick building's interior was redesigned by Frank Israel in 1990 as a creative workspace, opening up the interior and creating sightlines all the way through the building.[43]

Originally located at the Venice home of Pritzker Prize–winning architect and SCI-Arc founder Thom Mayne, the Architecture Gallery was in existence for just ten weeks in 1979 and featured new work by then-emerging architects Frank Gehry, Eric Owen Moss, and Morphosis.[44] Constructed on a long, narrow lot in 1981, the Indiana Avenue Houses/Arnoldi Triplex was designed Frank Gehry in partnership with artists Laddie Dill and Charles Arnoldi.[43] Frank Gehry has designed several well-known houses in Venice, including the Jane Spiller House (completed 1979) and the Norton House (completed 1984) on Venice Beach.[45] In 1994, sculptor Robert Graham designed a fortress-like art studio and residence for himself and his wife, actress Anjelica Huston, on Windward Avenue.[46]

Art

In the 1970s, prominent performance artist Chris Burden created some of his early, groundbreaking work in Venice, such as Trans-fixed.[47] Other notable artists who maintained studios in the area include Charles Arnoldi, Jean-Michel Basquiat,[48] John Baldessari, Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, James Georgopoulos, Dennis Hopper, and Ed Ruscha.[49] Organized by the Hammer Museum over the course of one weekend in 2012,[50] the open-air Venice Beach Biennial (in reference to the Venice Biennale in Italy) brought together 87 artists, including site-specific projects by established artists like Evan Holloway, Barbara Kruger as well as boardwalk veteran Arthure Moore.[51] In the 1980s and 1990s Venice Beach became a mecca for street performing turning it into a tourist attraction that rivaled many of southern California's other destinations. Chainsaw jugglers, acrobats and comics like Michael Colyar could be seen on a daily basis. Many performers like the Jim Rose Circus got their start on the boardwalk.

Music

Venice was where legendary rock band The Doors were formed in 1965 by UCLA alums and Venice bohemians Ray Manzarek and Jim Morrison. The Doors would go on to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and are considered one of the greatest rock groups of all time, with Morrison being considered one of the greatest rock frontmen. Venice would also be the birthplace of another legendary rock band in the 1980s in Jane's Addiction. Perry Farrell, frontman and founder of Lollapalooza, was a longtime Venice resident until 2010.[52][53]

Venice in the 1980s also had a large number of bands playing music known as crossover thrash, a hardcore punk/thrash metal musical hybrid. The most notable of these bands is Suicidal Tendencies. Other Venice bands such as Beowülf, No Mercy, and Excel were also featured on the rare compilation album Welcome to Venice.

Government and infrastructure

Venice is a neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles represented by District 11 on the Los Angeles City Council. City services are provided by the city of Los Angeles. There is a Venice Neighborhood Council that advises the LA City Council on local issues.

Local government

The Los Angeles Fire Department operates Station 63, which serves Venice with two engines, a truck, and an ALS rescue ambulance.

Los Angeles Police Department serves the area through the Pacific Community Police Station at 12312 Culver Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90066, and a beach sub-station at 1530 W. Ocean Front Walk, Venice, CA 90921.[54]

- Los Angeles County Lifeguards

Venice Beach is the headquarters of the Lifeguard Division of the Los Angeles County Fire Department. It is located at 2300 Ocean Front Walk. It is the nation's largest ocean lifeguard organization with over 200 full-time and 700 part-time or seasonal lifeguards. The headquarters building used to be the City of Los Angeles Lifeguard Headquarters until Los Angeles City and Santa Monica Lifeguards were merged into the County in 1975.

The Los Angeles County Lifeguards safeguard 31 miles (50 km) of beach and 70 miles (110 km) of coastline, from San Pedro in the south, to Malibu in the north. Lifeguards also provide Paramedic and rescue boat services to Catalina Island, with operations out of Avalon and the Isthmus.

Lifeguard Division employs 120 full-time and 600 seasonal lifeguards, operating out of three sectional headquarters, Hermosa, Santa Monica, and Zuma beach. Each of these headquarters staffs a 24-hour EMT-D response unit and are part of the 911 system. In addition to providing for beach safety, Los Angeles County Lifeguards have specialized training for Baywatch rescue boat operations, underwater rescue and recovery, swiftwater rescue, cliff rescue, marine mammal rescue and marine firefighting.

County, state and federal representation

The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services SPA 5 West Area Health Office serves Venice.[55]

The United States Postal Service operates the Venice Post Office at 1601 Main Street and the Venice Carrier Annex at 313 Grand Boulevard.[56][57]

Education

Forty-nine percent of Venice residents aged 25 and older had earned a four-year degree by 2000, a high figure for both the city and the county. The percentages of residents of that age with a bachelor's degree or a master's degree was considered high for the county.[10]

Schools

The schools within Venice are as follows:[58]

- Broadway Elementary School, LAUSD, 1015 Lincoln Boulevard

- Animo Venice Charter High School, 820 Broadway Street, which opened in August 2002 with 145 students, adding a freshman class of 140 every year until 2006, when it reached its full capacity of approximately 525 students. The school moved in 2006 to the former Ninety-Eighth Street Elementary School campus, which had been occupied by the Renaissance Academy.

- Venice Skills Center, LAUSD, 611 Fifth Avenue

- First Lutheran School of Venice, private, 815 Venice Boulevard

- Westminster Avenue Elementary School, LAUSD, 1010 Abbot Kinney Boulevard

- St. Mark School, private elementary, 912 Coeur d'Alene Avenue

- Coeur d'Alene Avenue Elementary School, LAUSD, 810 Coeur d'Alene Avenue

- Westside Leadership Magnet School, LAUSD alternative, 104 Anchorage Street

Public libraries

The Los Angeles Public Library operates the Venice–Abbot Kinney Memorial Branch.[59]

Parks and recreation

The Venice Beach Recreation Center comprises a number of facilities sprawling between Ocean Front Walk and the bike path, Horizon Ave to the north, and N.Venice Blvd to the south. The installation has basketball courts (unlighted/outdoor), several children play areas with a gymnastics apparatus, handball courts (unlighted), paddle tennis courts (unlighted), and volleyball courts (unlighted). At the south end of the area is the famous muscle beach outdoor gymnasium. In March 2009, the city opened a sophisticated $2,000,000 skate park on the sand towards the north. While not technically part of the park the Graffiti Walls on the beach side of the bike path in the same vicinity.[60]

The Oakwood Recreation Center is located at 767 California Ave. The center, which also acts as a Los Angeles Police Department stop-in center, includes an auditorium, an unlighted baseball diamond, lighted indoor basketball courts, unlighted outdoor basketball courts, a children's play area, a community room, a lighted American football field, an indoor gymnasium without weights, picnic tables, and an unlighted soccer field.[61]

The Westminster Off-Leash Dog Park is in Venice.[62]

Venice in media

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

Dozens of movies and hundreds of television shows and even video games have used locations in Venice, including its beach, its pleasure piers, the canals and colonnades, the boardwalk, the high school, even a particular hamburger stand.[63] Some of them are:

- 1914: Kid Auto Races at Venice (Charlie Chaplin—first appearance of the "Little Tramp" character.)

- 1920: Number, Please? (Harold Lloyd)[64]

- 1921: The High Sign (Buster Keaton)[65]

- 1923: The Balloonatic (Buster Keaton)[66]

- 1927: Sugar Daddies (Laurel and Hardy)

- 1928: The Circus (Charlie Chaplin)

- 1928: The Cameraman (Buster Keaton)[67]

- 1958: Touch of Evil (Orson Welles)—Shot entirely in Venice except for one indoor scene, selected by Welles as a stand-in for a fictional run-down Mexican border town.

- 1961: Night Tide (Dennis Hopper, Linda Lawson, written and directed by Curtis Harrington)—Shot entirely in Venice and shows the deteriorated nature of the area in the 1950s.

- 1972: One Pair of Eyes - Reyner Banham loved Los Angeles — architectural critic Reyner Banham explores Los Angeles in 1972. See the movie on Vimeo

- 1976: The Witch Who Came from the Sea (Millie Perkins, directed by Matt Cimber)

- 1979: Roller Boogie (Linda Blair, directed by Mark L. Lester)

- 1988: Colors

- 1991: The Doors (Val Kilmer, directed by Oliver Stone)

- 1992: White Men Can't Jump

- 1993: Falling Down

- 1994: Speed (Keanu Reeves)

- 1998: The Big Lebowski

- 1998: American History X

- 2001: Dogtown and Z-Boys

- 2003: Thirteen (Holly Hunter)

- 2004: Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas as Verona Beach

- 2005: Lords of Dogtown

- 2006: Tenacious D in The Pick of Destiny

- 2007: Californication

- 2011: Wilfred (U.S. TV series)

- 2013: Grand Theft Auto V as Vespucci Beach

- 2013: Sugar

- 2013-2014: Sam & Cat

- 2009–present: American Ninja Warrior

- 2014: Alex of Venice

- 2015: The Amazing Race

- 2016: Flaked

Notable people

- Sky Ferreira, singer-songwriter, model, actress

- Jay Adams, professional skateboarder, original member of the Z-Boys skateboard team

- J.C. Barthel, Venice postmaster and commissioner of supplies, 1920s, president of the Chamber of Commerce

- Charles Winchester Breedlove, Los Angeles City Council member, 1933–45, supported legalized tango games

- Brun Campbell, folk ragtime musician.

- Marton Csokas, actor

- John J. Coit, builder and operator of the Venice Miniature Railway

- Hulk Hogan, professional wrestler (kayfabe)

- Abbot Kinney, developer of Venice of America

- John Lovell, businessman, member of the Los Angeles Common Council

- Matt Sorum, drummer, formerly in Guns n' Roses, Velvet Revolver, and the Cult

- James Edwin Richards, crime activist and citizen journalist, editor and publisher

- Ronda Rousey, mixed martial artist, judoka and actress[68]

- Karl L. Rundberg, Los Angeles City Council member (1957–65), opposed Venice beatniks

- Joanie Sommers, singer

- Anna Paquin, actress[69]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Los Angeles Times Neighborhood Project". Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ diseno Rancho La Ballona

- ^ 1900 USGS topographic map

- ^ Map of old Spanish and Mexican ranchos in Los Angeles County

- ^ a b Elayne Alexander; Bryan L. Mercer (February 2, 2009). Venice. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6966-6. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Maynard, John Arthur (1993). Venice West: The Beat Generation in Southern California. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1965-9.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Coast as a Public Place". Geographical Review. 95 (4): 578–593. October 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2005.tb00382.x.

- ^ Romero, Dennis (November 6, 2003). "Gangster's Paradise Lost". Los Angeles City Beat. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ Venice in Magazines etc. Virtualvenice.info.

- ^ a b c d e f "Venice," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ Donna Kardos Yesalavich (April 1, 2014), Cut! Actress Anjelica Huston Finds a Buyer Wall Street Journal.

- ^ [1] "Westside," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ The Thomas Guide: Los Angeles County, 2004, pages 671, 672 and 702

- ^ http://cityplanning.lacity.org/complan/pdf/vencptxt.pdf

- ^ https://www.google.com/search?q=zimas&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a&channel=sb

- ^ Janelle Brown (November 20, 2005), Venice, Calif., Is Turning Into Sunrise Boulevard New York Times

- ^ Nancy Hill-Holtzman (August 10, 1989), Plan for Kinney Boulevard in Venice Runs Into Pothole Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Nancy Hill-Holtzman (February 25, 1990), Part of Washington Blvd. to Be Renamed Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Departures: Venice - Chapter 5: Abbot Kinney Boulevard KCET.

- ^ Groves, Martha (October 25, 2013) "Abbot Kinney Boulevard's renaissance a mixed blessing" Los Angeles Times

- ^ McKenna, Kristine (October 9, 2003). "The Ace is Wild: The Doug Chrismas Story". LA Weekly. Retrieved January 26, 2012. (sic: Spelling of "Chrismas")

- ^ Venice Post Office Los Angeles Conservancy Retrieved April 24, 2014

- ^ Tobar, Hector (November 11, 2011), There's a special stamp on the Venice post office Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Groves, Martha (January 7, 2010), Producer Joel Silver buys former U.S. post office in Venice Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Vankin, Deborah, (June 17, 2014) "Restored 'Abbot Kinney' mural anchors exhibit on Venice history" Los Angeles Times

- ^ Groves, Martha (October 11, 2012), Joel Silver to put his stamp on Venice Post Office Los Angeles Times

- ^ Hiatt, Anna (January 20, 2014) "Congress wants delay in selling of historic post offices until federal report is completed" Washington Post

- ^ freevenicebeachhead (June 12, 2016). "Judge Garland Stumbles Over The Venice Post Office". Free Venice Beachhead. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Leah Ziskin (August 12, 2007), It's purely pedestrian Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ari Bloomekatz and Abby Sewell, "Car Plows Through Crowd on Venice Boardwalk, Killing One," Los Angeles Times, August 3, 2013

- ^ David Zahniser and Matt Stevens, "L.A. City Council Calls for Boardwalk Barriers in Venice," Los Angeles Times, August 6, 2013

- ^ "Court profile of Venice Beach basketball court". courtsoftheworld.com.

- ^ Lapper, Richard (August 31, 2007). "Migrant villages breathe life into the old country; [LONDON 2ND EDITION]". Financial Times. London. p. 9.

- ^ Rong-Gong Lin II (October 12, 2010), $1.6-million county project approved to replace sand on Venice Beach Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Stevens, Matt (December 11, 2012). "Venice's new bloom". Los Angeles Times. pp. A1, A15. Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ http://www.lacitybeat.com/article.php?id=362&IssueNum=22

- ^ http://www.sioc.ucla.edu/main.asp?nav=projects&nav=XINACHTLI

- ^ [2] multifamilybiz.com

- ^ Martha Groves (May 26, 2010). "Los Angeles, developer reach deal to preserve Venice's landmark Lincoln Place apartments". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Dave, Paresh (March 31, 2015). "Is Snapchat's rapid growth changing Venice's funky vibe?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ http://www.virtualvenice.info/poets/index.htm

- ^ Roger Vincent (July 15, 2012), Former Eames furniture design headquarters sold in Venice Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Eve Bachrach (May 3, 2013), Touring 3 of Venice's Modern Arch Gems of the '70s and '80s Curbed LA.

- ^ A Confederacy of Heretics: The Architecture Gallery, Venice, 1979; Southern California Institute of Architecture, Los Angeles; March 29 - July 7, 2013 Graham Foundation, Chicago.

- ^ Mildred Friedman (2009) "Frank Gehry The Houses", Rozzoli, New York

- ^ Lauren Beale (March 7, 2012), Venice live/work space of Anjelica Huston, Robert Graham for sale Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Chris Burden at Virtual Venice". Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- ^ Fred Hoffman (March 13, 2005), Basquiat's L.A. Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Edward Wyatt (August 11, 2008), Economic Realities Press on Artists’ Outdoor Eden New York Times.

- ^ The Venice Beach Biennial Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

- ^ Jori Finkel (July 11, 2012), Venice Beach gets a breezy Biennial on the boardwalk Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Venice native, Perry Farrel & Jane's Addiction are back | FREE Download off their new album due out in August". WE LOVENICE. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "Alt-rocker Perry Farrell breaks his Venice addiction". Los Angeles Times. May 26, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Pacific Community Police Station – official website of THE LOS ANGELES POLICE DEPARTMENT. Lapdonline.org.

- ^ "About Us." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Post Office Location – VENICE." United States Postal Service. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ "Post Office Location – VENICE CARRIER ANNEX." United States Postal Service. Retrieved December 6, 2008.

- ^ [3] "Venice Schools," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- ^ "Venice – Abbot Kinney Memorial Branch." Los Angeles Public Library. Retrieved March 18, 2010.

- ^ "Venice Beach Recreation Center." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "[4]." City of Los Angeles. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Home page." Westminster Off-Leash Dog Park. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Venice – Movie Making and TV shows at Venice Beach. Westland.net (November 11, 2006).

- ^ Number, Please? at IMDb

- '^ The High 'Sign at IMDb

- ^ The Balloonatic at IMDb

- ^ The Cameraman at IMDb

- ^ VenicePaparazzi (February 23, 2013) "Venice resident Ronda Rousey wins with an arm bar submission at UFC 157!"

- ^ "Anna Paquin and Stephen Moyer Get Married!". Us Weekly. August 21, 2010.

Further reading

- Deener, Andrew (2012). Venice: A Contested Bohemia in Los Angeles. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-14000-1. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- Maynard, John Arthur (1993). Venice West: The Beat Generation in Southern California. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1965-9.

- Stanton, Jeffrey (2005). Venice, California: Coney Island of the Pacific. Donahue Publishing. ISBN 0-9619849-3-7. History of Venice with 367 historic photographs.

External links

- Venice Departures KCET – Online documentary series by public broadcaster KCET mapping L.A. neighborhoods

- Venice, Los Angeles

- Beaches of Southern California

- Former municipalities in California

- Neighborhoods in Los Angeles

- Landmarks in Los Angeles

- Parks in Los Angeles

- Populated coastal places in California

- Populated places established in 1822

- Hollywood history and culture

- Busking venues

- Defunct amusement parks in California

- Seaside resorts in California

- Westside (Los Angeles County)

- Beaches of Los Angeles County, California