West Africa

| West Africa | |

|---|---|

| Area | 5,112,903 km2 (7th)[1] |

| Population | 340,000,000 (2013 est.) (4th)[1] |

| Density | 49.2/km2 (127.5/sq mi)[1] |

| Demonym | West African |

| Countries | |

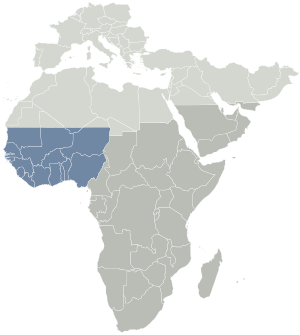

West Africa, also called Western Africa and the West of Africa, is the westernmost subregion of Africa. West Africa has been defined as including the 18 countries Benin, Burkina Faso, the island of Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, the island of Saint Helena, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sao Tome and Principe and Togo.[6]

History

The history of West Africa can be divided into five major periods: first, its prehistory, in which the first human settlers arrived, developed agriculture, and made contact with peoples to the north; the second, the Iron Age empires that consolidated both intra-African, and extra-African trade, and developed centralized states; third, major polities flourished, which would undergo an extensive history of contact with non-Africans; fourth, the colonial period, in which Great Britain and France controlled nearly the whole of the region; and fifth, the post-independence era, in which the current nations were formed.

Prehistory

Early human settlers from northern Holocene societies arrived in West Africa around 12,000 B.C.[dubious – discuss] Sedentary farming began in, or around the fifth millennium B.C, as well as the domestication of cattle. By 1500 B.C, ironworking technology allowed an expansion of agricultural productivity, and the first city-states later formed. Northern tribes developed walled settlements and non-walled settlements that numbered at 400. In the forest region, Iron Age cultures began to flourish, and an inter-region trade began to appear. The desertification of the Sahara and the climatic change of the coast cause trade with upper Mediterranean peoples to be seen.

The domestication of the camel allowed the development of a trans-Saharan trade with cultures across the Sahara, including Carthage and the Berbers; major exports included gold, cotton cloth, metal ornaments and leather goods, which were then exchanged for salt, horses, textiles, and other such materials. Local leather, cloth, and gold also contributed to the abundance of prosperity for many of the following empires.

Empires

The development of the region's economy allowed more centralized states and civilizations to form, beginning with the Nok culture that began in 1000 B.C. and the Ghana Empire that first flourished between the 1st and 3rd centuries, which later gave way to the Mali Empire. In current-day Mauritania, there exist archaeological sites in the towns of Tichit and Oualata that were initially constructed around 2000 B.C., and were found to have originated from the Soninke branch of the Mandé peoples. Also, based on the archaeology of city of Kumbi Saleh in modern-day Mauritania, the Mali empire came to dominate much of the region until its defeat by Almoravid invaders in 1052.

Three great kingdoms were identified in Bilad al-Sudan by the ninth century. They included Ghana, Gao and Kanem.[7]

The Sosso Empire sought to fill the void, but was defeated (c. 1240) by the Mandinka forces of Sundiata Keita, founder of the new Mali Empire. The Mali Empire continued to flourish for several centuries, most particularly under Sundiata's grandnephew Musa I, before a succession of weak rulers led to its collapse under Mossi, Tuareg and Songhai invaders. In the 15th century, the Songhai would form a new dominant state based on Gao, in the Songhai Empire, under the leadership of Sonni Ali and Askia Mohammed.

Meanwhile, south of the Sudan, strong city states arose in Igboland, such as the 10th-century Kingdom of Nri, which helped birth the arts and customs of the Igbo people, Bono in the 12th century, which eventually culminated in the formation the all-powerful Akan Empire of Ashanti, while Ife and Benin City rose to prominence around the 14th century. Further east, Oyo arose as the dominant Yoruba state and the Aro Confederacy as a dominant Igbo state in modern-day Nigeria.

Slavery and European contact

Portuguese traders began establishing settlements along the coast in 1445, followed by the French, English, Spanish, Danish and Dutch; the African slave trade began not long after, which over the following centuries would debilitate the region's economy and population. The slave trade also encouraged the formation of states such as the Asante Empire, Bambara Empire and Dahomey, whose economic activities include but not limited to exchanging slaves for European firearms.

Colonialism

In the early 19th century, a series of Fulani reformist jihads swept across Western Africa. The most notable include Usman dan Fodio's Fulani Empire, which replaced the Hausa city-states, Seku Amadu's Massina Empire, which defeated the Bambara, and El Hadj Umar Tall's Toucouleur Empire, which briefly conquered much of modern-day Mali.

However, the French and British continued to advance in the Scramble for Africa, subjugating kingdom after kingdom. With the fall of Samory Ture's new-founded Wassoulou Empire in 1898 and the Ashanti queen Yaa Asantewaa in 1902, most West African military resistance to colonial rule resulted in failure.

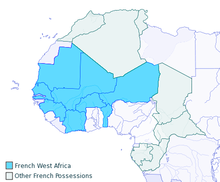

Britain controlled the Gambia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, and Nigeria throughout the colonial era, while France unified Senegal, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Benin, Ivory Coast and Niger into French West Africa. Portugal founded the colony of Guinea-Bissau, while Germany claimed Togoland, but was forced to divide it between France and Britain following First World War due to the Treaty of Versailles. Only Liberia retained its independence, at the price of major territorial concessions.

Postcolonial eras

Following World War II, nationalist movements arose across West Africa. In 1957, Ghana, under Kwame Nkrumah, became the first sub-Saharan colony to achieve its independence, followed the next year by France's colonies (Guinea in 1958 under the leadership of President Ahmed Sekou Touré); by 1974, West Africa's nations were entirely autonomous.

Since independence, many West African nations have been submerged under political instability, with notable civil wars in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ivory Coast, and a succession of military coups in Ghana and Burkina Faso.

Since the end of colonialism, the region has been the stage for some brutal conflicts, including:

- Nigerian Civil War

- First Liberian Civil War

- Second Liberian Civil War

- Guinea-Bissau Civil War

- Ivorian Civil War

- Sierra Leone Rebel War

States

The Economic Community of West African States, established in May 1975, has defined the region of West Africa since 1999 as including the following 15 states:[6]

| * Benin * Burkina Faso * Cape Verde * Ivory Coast * Gambia | * Ghana * Guinea * Guinea-Bissau * Liberia * Mali | * Niger * Nigeria * Senegal * Sierra Leone * Togo * Cameroon |

Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Western Africa includes the preceding states with the addition of Mauritania (which withdrew from ECOWAS in 1999), comprising an area of approximately 6.1 million square km.[8] The UN region also includes the island of Saint Helena, a British overseas territory in the south Atlantic Ocean.

Area

In the United Nations scheme of African regions, the region includes 16 states and the island of Saint Helena, an overseas territory:[9]

- Mali, Burkina Faso, Senegal and Niger are mostly in the Sahel, a transition zone between the Sahara desert and the Sudanian Savanna.

- Benin, Cote d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Nigeria compose Guinea, the traditional name for the area near the Gulf of Guinea.

- Cape Verde is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean.

- Mauritania lies in the Maghreb, the northwestern region of Africa that has historically been inhabited by both traditionally West African groups such as the Fulani, Soninke and Wolof, along with Arab-Berber Maghrebi people. Due to its increasingly close ties to the Arab World and its 1999 withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), in modern times it is often considered, especially in Africa, as now part of western North Africa.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

Geography and climate

West Africa, broadly defined to include the western portion of the Maghreb (Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia), occupies an area in excess of 6,140,000 km2, or approximately one-fifth of Africa. The vast majority of this land is plains lying less than 300 meters above sea level, though isolated high points exist in numerous states along the southern shore of West Africa.[16]

| West Africa Tropical Ecozone | ||

|

Benin Burkina Faso Gambia Ghana Guinea-Bissau Guinea Ivory Coast Liberia Mali Mauritania Nigeria Niger Senegal Sierra Leone Togo |

|

|

| State | The biostate | Location in Afrotropic |

The northern section of West Africa (narrowly defined to exclude the western Maghreb) is composed of semi-arid terrain known as Sahel, a transitional zone between the Sahara and the savannahs of the western Sudan. Forests form a belt between the savannas and the southern coast, ranging from 160 km to 240 km in width.[17]

The northwest African region of Mauritania periodically suffers country-wide plagues of locusts which consume water, salt and crops on which the human population relies.[18]

Background

West Africa is west of an imagined north-south axis lying close to 10° east longitude.[16] The Atlantic Ocean forms the western as well as the southern borders of the West African region.[16] The northern border is the Sahara Desert, with the Ranishanu Bend generally considered the northernmost part of the region.[19] The eastern border is less precise, with some placing it at the Benue Trough, and others on a line running from Mount Cameroon to Lake Chad.

Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states.[20]

In contrast to most of Central, Southern and Southeast Africa, West Africa is not populated by Bantu-speaking peoples.[21]

Transport

Rail transport

A Trans-ECOWAS project, established in 2007, plans to upgrade railways in this zone. One of the goals of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is the development of an integrated railroad network.[22] Aims include the extension of railways in member countries, the interconnection of previously isolated railways and the standardisation of gauge, brakes, couplings, and other parameters. The first line would connect the cities and ports of Lagos, Cotonou, Lomé and Accra and would allow the largest container ships to focus on a smaller number of large ports, while efficiently serving a larger hinterland. This line connects 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge and 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge systems, which would require four rail dual gauge, which can also provide standard gauge.[22]

Road transport

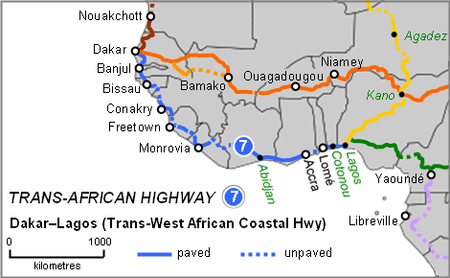

The Trans–West African Coastal Highway is a transnational highway project to link 12 West African coastal states, from Mauritania in the north-west of the region to Nigeria in the east, with feeder roads already existing to two landlocked countries, Mali and Burkina Faso.[23]

The eastern end of the highway terminates at Lagos, Nigeria. Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) consider its western end to be Nouakchott, Mauritania, or to be Dakar, Senegal, giving rise to these alternative names for the road:

- Nouakchott–Lagos Highway

- Lagos–Nouakchott Highway

- Dakar–Lagos Highway

- Lagos–Dakar Highway

- Trans-African Highway 7 in the Trans-African Highway network

Air transport

The capital's airports include:

- Cadjehoun Airport (COO) International; Cotonou, Benin

- Ouagadougou Airport (OUA); Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

- Amílcar Cabral International Airport (SID); Praia, Cape Verde

- Banjul International Airport (BJL) International; Banjul, Gambia

- Kotoka International Airport (ACC); Accra; Ghana

- Conakry International Airport (CKY); Conakry, Guinea

- Osvaldo Vieira International Airport (OXB); Bissau, Guinea-Bissau

- Port Bouet Airport (ABJ); Abidjan, Ivory Coast

- Roberts International Airport (ROB); Monrovia, Liberia

- Bamako–Sénou International Airport (BKO); Bamako, Mali

- Diori Hamani International Airport (NIM); Niamey, Niger

- Murtala Muhammed International Airport (LOS); Lagos, Nigeria

- Saint Helena Airport; Jamestown, Saint Helena

- Léopold Sédar Senghor International Airport (DKR); Dakar, Senegal

- Lungi International Airport (FNA); Freetown, Sierra Leone

- Lomé–Tokoin Airport (LFW); Lomé, Togo

Of the sixteen, the most important hub and entry point to West Africa is Kotoka International Airport, and Murtala Muhammed International Airport, offering many international connections.

Culture

Despite the wide variety of cultures in West Africa, from Nigeria through to Senegal, there are general similarities in dress, cuisine, music and culture that are not shared extensively with groups outside the geographic region. This long history of cultural exchange predates the colonization era of the region and can be approximately placed at the time of the Ghana Empire (proper: Wagadou Empire), Mali Empire or perhaps before these empires.

Traditional architecture

The main traditional styles of building (in conjunction with modern styles) are the distinct Sudano-Sahelian style in inland areas, and the coastal forest styles more reminiscent of other sub-Saharan areas. They differ greatly in construction due to the demands made by the variety of climates in the area, from tropical humid forests to arid grasslands and desert. Despite the architectural differences, buildings perform similar functions, including the compound structure central to West African family life or strict distinction between the private and public worlds needed to maintain taboos or social etiquette.

Clothing

In contrast to other parts of the continent south of the Sahara Desert, the concepts of hemming and embroidering clothing have been traditionally common to West Africa for centuries, demonstrated by the production of various breeches, shirts, tunics and jackets. As a result, the peoples of the region's diverse nations wear a wide variety of clothing with underlying similarities. Typical pieces of west African formal attire include the knee-to-ankle-length, flowing Boubou robe, Dashiki, and Senegalese Kaftan (also known as Agbada and Babariga), which has its origins in the clothing of nobility of various West African empires in the 12th century. Traditional half-sleeved, hip-long, woven smocks or tunics (known as fugu in Gurunsi, riga in Hausa) -- worn over a pair of baggy trousers—is another popular garment.[24] In the coastal regions stretching from southern Ivory Coast to Benin, a huge rectangular cloth is wrapped under one arm, draped over a shoulder, and held in one of the wearer's hands—coincidentally, reminiscent of Romans' togas. The best-known of these toga-like garments is the Kente (made by the Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast), who wear them as a gesture of national pride.

Cuisine

Scores of foreign visitors to West African nations (e.g., traders, historians, emigrants, colonists, missionaries) have benefited from its citizens' generosity, and even left with a piece of its cultural heritage, via its foods. West African cuisines have had a significant influence on those of Western civilization for centuries; several dishes of West African origin are currently enjoyed in the Caribbean (e.g., the West Indies and Haiti); Australia; the USA (particularly Louisiana, Virginia, North and South Carolina); Italy; and other countries. Although some of these recipes have been altered to suit the sensibilities of their adopters, they retain a distinct West African essence.[25]

West Africans cuisines include fish (especially among the coastal areas), meat, vegetables, and fruits—most of which are grown by the nations' local farmers. In spite of the obvious differences among the various local cuisines in this multinational region, the foods display more similarities than differences. The small difference may be in the ingredients used. Most foods are cooked via boiling or frying. Commonly featured, starchy vegetables include yams, plantains, cassava, and sweet potatoes.[26] Rice is also a staple food, as is the Serer people's sorghum couscous (called "Chereh" in Serer) particularly in Senegal and the Gambia.[27] Jollof rice—originally from the Kingdom of Jolof (now part of modern-day Senegal) but having spread to the Wolofs of Gambia—is also enjoyed in many Western nations, as well;[28] Mafé (proper: "Tigh-dege-na" or Domodah) from Mali (via the Bambara and Mandinka)[29]—a peanut-butter stew served with rice;[30][31] Akara (fried bean balls seasoned with spices served with sauce and bread) from Nigeria is a favourite breakfast for Gambians and Senegalese, as well as a favourite side snack or side dish in Brazil and the Caribbean just as it is in West Africa. It is said that its exact origin may be from Yorubaland in Nigeria.[32][33] Fufu (from the Twi language, a dough served with a spicy stew or sauce for example okra stew etc.) from Ghana is enjoyed throughout the region and beyond even in Central Africa with their own versions of it.[34]

Recreation and sports

The board game oware is quite popular in many parts of West Africa. The word "Oware" originates from the Akan people of Ghana. However, virtually all African peoples have a version of this board game.[35] The major multi-sport event of West Africa is the ECOWAS Games which commenced at the 2012 ECOWAS Games. Football is also a pastime enjoyed by many, either spectating or playing. The major national teams of West Africa, the Ghana national football team, the Ivory Coast national football team, and the Nigeria national football team regularly win the Africa Cup of Nations.[36] Major football teams of West Africa are Asante Kotoko SC and Accra Hearts of Oak SC of the Ghana Premier League, Enyimba International of the Nigerian Premier League and ASEC Mimosas of the Ligue 1 (Ivory Coast). The football governing body of West Africa is the West African Football Union (WAFU) and the major tournament is the West African Club Championship and WAFU Nations Cup, along with the annual individual award of West African Footballer of the Year.[37][38]

Music

Mbalax, Highlife, Fuji and Afrobeat are all modern musical genres which listeners enjoy in this region. Old traditional folk music is also well preserved in this region. Some of these are religious in nature such as the "Tassou" tradition used in Serer religion.[39]

Griot and Praise-singing

Two important related traditions that musically make West African musical attitudes unique are the Griot tradition, and the Praise-singing tradition. In many cases, these two genres are highly similar, the difference being whether the traditions are considered the property of hereditary castes (Griot) or to talented individuals among a ruler's subjects (Praise-singing). In both cases the minstrel tradition and specialization in certain string and percussion instruments is observed.

Traditionally, musical and oral history as conveyed over generations by Griots are typical of West African culture in Mande, Wolof, Songhay, Moor and (to some extent, though not universal) Fula areas in the far west. A hereditary caste occupying the fringes of society, the Griots were charged with memorizing the histories of local rulers and personages and the caste was further broken down into music-playing Griots (similar to bards) and non-music playing Griots. Like Praise-singers, the Griot's main profession was musical acquisition and prowess, and patrons were the sole means of financial support. Modern Griots enjoy higher status in the patronage of rich individuals in places such as Mali, Senegal, Mauritania and Guinea, and to some extent make up the vast majority of musicians in these countries. Examples of modern popular Griot artists include Salif Keita, Youssou N'Dour, Mamadou Diabate, Rokia Traore and Toumani Diabate.

In other areas of West Africa, primarily among the Hausa, Mossi, Dagomba and Yoruba in the area encompassing Burkina Faso, northern Ghana, Nigeria and Niger, the traditional profession of non-hereditary praise-singers, minstrels, bards and poets play a vital role in extending the public show of power, lineage and prestige of traditional rulers through their exclusive patronage. Like the Griot tradition, praise singers are charged with knowing the details of specific historic events and royal lineages, but more importantly need to be capable of poetic improvisation and creativity, with knowledge of traditional songs directed towards showing a patron's financial and political or religious power. Competition between Praise-singing ensembles and artistes are high, and artists responsible for any extraordinarily skilled prose, musical compositions and panegyric songs are lavishly rewarded with money, clothing, provisions and other luxuries by patrons who are usually politicians, rulers, Islamic clerics and merchants; these successful praise-singers rise to national stardom. Examples include Mamman Shata, Souley Konko, Fati Niger, Saadou Bori and Dan Maraya. In the case of Niger, numerous praise songs are composed and shown on television in praise of local rulers, Islamic clerics and politicians.

Film industry

Nollywood of Nigeria, is the main film industry of West Africa. The Nigerian cinema industry is the second largest film industry in terms of number of annual film productions, ahead of the American film industry in Hollywood.[40] Senegal and Ghana also have long traditions of producing films. The late Ousmane Sembène, the Senegalese film director, producer and writer is from the region, as is the Ghanaian Shirley Frimpong-Manso.

Religion

Islam

Islam is the predominant religion of the West African interior and the far west coast of the continent (70% of West Africans); and was introduced to the region by traders in the 9th century. Islam is the religion of the region's biggest ethnic groups by population. Islamic rules on livelihood, values, dress and practices had a profound effect on the populations and cultures in their predominant areas, so much so that the concept of tribalism is less observed by Islamized groups like the Mande, Wolof, Hausa, Fula and Songhai, than they are by non-Islamized groups.[41] Ethnic intermarriage and shared cultural icons are established through a superseded commonality of belief or community, known as ummah.[42] Traditional Muslim areas include Senegal, Gambia, Mali, Mauritania, Guinea, Niger; the upper coast and inland two-thirds of Sierra Leone and inland Liberia; the western, northern and far-eastern regions of Burkina Faso; and the northern halves of the coastal nations of Nigeria, Benin, Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast.[43]

African traditional

Traditional African religions (noting the many different belief systems) are the oldest belief systems among the populations of this region, and include Akan religion, Yoruba religion, Odinani, and Serer religion. They are spiritual but also linked to the historical and cultural heritage of the people.[44] Although traditional beliefs vary from one place to the next, there are more similarities than differences.[45]

Christianity

Christianity, a relative newcomer introduced from the late 19th to mid- to late 20th centuries, is associated with the British and French colonisation eras. It has become the predominant religion in the central and southern part of Nigeria, and the coastal regions stretching from southern Ghana to coastal parts of Sierra Leone. Like Islam, elements of traditional African religion are mixed with Christianity.[46] This religion was brought to the region by European missionaries during the colonial era.[47]

Demographics and languages

West Africans primarily speak Niger–Congo languages, belonging mostly, though not exclusively, to its non-Bantu branches, though some Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic speaking groups are also found. The Niger–Congo-speaking Yoruba, Igbo, Fulani, Akan and Wolof ethnic groups are the largest and most influential. In the central Sahara, Mandinka or Mande groups are most significant. Chadic-speaking groups, including the Hausa, are found in more northerly parts of the region nearest to the Sahara, and Nilo-Saharan communities, such as the Songhai, Kanuri and Zarma, are found in the eastern parts of West Africa bordering Central Africa. The population of West Africa is estimated at 340 million people as of 2013.[1]

Economic and regional organizations

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), founded by the 1975 Treaty of Lagos, is an organization of West African states which aims to promote the region's economy. The West African Monetary Union (or UEMOA from its name in French, Union économique et monétaire ouest-africaine) is limited to the eight, mostly Francophone countries that employ the CFA franc as their common currency. The Liptako-Gourma Authority of Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso seeks to jointly develop the contiguous areas of the three countries.

Women's peace movement

Since the adoption of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 in 2000, women have been engaged in rebuilding war-torn Africa. Starting with the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace and Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET), the peace movement has grown to include women across West Africa.

Established on May 8, 2006, Women Peace and Security Network - Africa (WIPSEN-Africa), is a women-focused, women-led Pan-African non-governmental organization based in Ghana.[48] The organization has a presence in Ghana, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Regional leaders of nonviolent resistance include Leymah Gbowee,[49] Comfort Freeman, and Aya Virginie Toure.

Pray the Devil Back to Hell is a documentary film about the origin of this peace movement. The film has been used as an advocacy tool in post-conflict zones like Sudan and Zimbabwe, mobilizing African women to petition for peace and security.[50]

Cityscapes of largest cities

Gallery

- Capital cities of West Africa

-

Praia, Cape Verde

-

Dakar, Senegal

-

Lomé, Togo

-

Cotonou, Benin

-

Niamey, Niger

-

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

-

Freetown, Sierra Leone

-

Banjul, Gambia

-

Conakry, Guinea

-

Bissau, Guinea-Bissau

-

Monrovia, Liberia

-

Bamako, Mali

-

Jamestown, Saint Helena

-

Georgetown, Ascension Island

See also

- Ajami

- Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa

- Manillas, a form of archaic money unique to West Africa

- N'Ko

- Nsibidi Script, an indigenously developed West African writing system

- Vai syllabary

- West African Craton

- Western Sahara

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Data and Statistics gathered from the West Africa Economic Community of West African States.

- ^ "IMF GDP data, September 2011". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "IMF GDP data, September 2011". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b "IMF GDP data, October 2013". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Nigerian Economy Overtakes South Africa's on Rebased GDP". Bloomberg L.P. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b Paul R. Masson, Catherine Anne Pattillo, "Monetary union in West Africa (ECOWAS): is it desirable and how could it be achieved?" (Introduction). International Monetary Fund, 2001. ISBN 1-58906-014-8

- ^ Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. New York: Methuen & Co Ltd. p. 3. ISBN 0841904316.

- ^ The UN office for West Africa

- ^ "United Nations Statistics Division - Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Office for North Africa of the Economic Commission for Africa". United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "2014 UNHCR country operations profile - Mauritania". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "African Development Bank Group: Mauritania". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Facts On File, Incorporated, Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East (2009), p. 448, ISBN 143812676X: "The Islamic Republic of Mauritania, situated in western North Africa..."

- ^ David Seddon, A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East (2004), ISBN 020340291X: "We have, by contrast, chosen to include the predominantly Arabic-speaking countries of western North Africa (the Maghreb), including Mauritania (which is a member of the Arab Maghreb Union)..."

- ^ Mohamed Branine, Managing Across Cultures: Concepts, Policies and Practices (2011), p. 437, ISBN 1849207291: "The Magrebian countries or the Arab countries of western North Africa (Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia)..."

- ^ a b c Peter Speth. Impacts of Global Change on the Hydrological Cycle in West and Northwest Africa, p. 33. Springer, 2010. ISBN 3-642-12956-0

- ^ Peter Speth. Impacts of Global Change on the Hydrological Cycle in West and Northwest Africa, p. 33. Springer, 2010. Prof. Kayode Omitoogun 2011, ISBN 3-642-12956-0

- ^ National Geographic, February 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Anthony Ham. West Africa, p. 79. Lonely Planet, 2009. ISBN 1-74104-821-4

- ^ Celestine Oyom Bassey, Oshita Oshita. Governance and Border Security in Africa, p. 261. African Books Collective, 2010. ISBN 978-8422-07-1

- ^ Ian Shaw, Robert Jameson. A Dictionary of Archaeology, p. 28. Wiley-Blackwell, 2002. ISBN 0-631-23583-3

- ^ a b "Proposed Ecowas railway". railwaysafrica.com.

- ^ Itai Madamombe (2006): "NEPAD promotes better transport networks", Africa Renewal, Vol. 20, No. 3 (October 2006), p. 14.

- ^ Barbara K. Nordquist, Susan B. Aradeon, Howard University. School of Human Ecology, Museum of African Art (U.S.). Traditional African dress and textiles: an exhibition of the Susan B. Aradeon collection of West African dress at the Museum of African Art (1975), pp. 9-15.

- ^ Chidi Asika-Enahoro. A Slice of Africa: Exotic West African Cuisines, Introduction. iUniverse, 2004. ISBN 0-595-30528-8.

- ^ Pamela Goyan Kittler, Kathryn Sucher. Food and Culture, p. 212. Cengage Learning, 2007. ISBN 0-495-11541-X.

- ^ UNESCO. The Case for indigenous West African food culture, p. 4. BREDA series, Vol. 9 (1995), (UNESCO).

- ^ Alan Davidson, Tom Jaine. The Oxford Companion to Food, p. 423. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-19-280681-5.

- ^ Mafé or Maafe is a Wolof word for it, the proper name is "Domodah" among the Mandinka people of Senegal and Gambia, who are the originators of this dish, or "Tigh-dege-na" among the Bambara people or Mandinka people of Mali. "Domodah" is also used by all Senegambians borrowed from the Mandinka language.

- ^ James McCann. Stirring the Pot: A History of African Cuisine, p. 132. Ohio University Press, 2009. ISBN 0-89680-272-8.

- ^ Emma Gregg, Richard Trillo. Rough Guide to the Gambia, p. 39. Rough Guides, 2003. ISBN 1-84353-083-X.

- ^ Carole Boyce Davies. Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora: Origins, Experiences and Culture, Volume 1, p. 72. ABC-CLIO, 2008. ISBN 1-85109-700-7.

- ^ Toyin Ayeni. I Am a Nigerian, Not a Terrorist, p. 2. Dog Ear Publishing, 2010. ISBN 1-60844-735-9.

- ^ Dayle Hayes, Rachel Laudan. Food and Nutrition. Dayle Hayes, Rachel Laudan, editorial advisers. Volume 7, p. 1097. Marshall Cavendish, 2008. ISBN 0-7614-7827-2.

- ^ West Africa, issues 4106–4119, pp. 1487-8. Afrimedia International, (1996)

- ^ "Why does the West dominate African football?" BBC.

- ^ "Wafu Cup to make a comeback". BBC Sport. 29 September 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Caf have split the West African Football Union into two separate zones". Goal.com. Goal.com. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Ali Colleen Neff, Tassou: the Ancient Spoken Word of African Women. 2010.

- ^ "Nigeria surpasses Hollywood as world's second largest film producer – UN". United Nations. 5 May 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- ^ The Islamic World to 1600: The Fractured Caliphate and the Regional Dynasties (West Africa)

- ^ Muslim Societies in African History (New Approaches to African History), David Robinson, Chapter 1.

- ^ Spread of Islam in West Africa (part 1 of 3): The Empire of Ghana , Prof. A. Rahman I. Doi, Spread of Islam in West Africa. http://www.islamreligion.com/articles/304/

- ^ John S. Mbiti. Introduction to African Religion, p. 19. East African Publishers, 1992. ISBN 9966-46-928-1

- ^ William J. Duiker, Jackson J. Spielvogel. World History: To 1800, p. 224. Cengage Learning, 2006. ISBN 0-495-05053-9

- ^ Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong. Themes in West Africa's History, p. 152. James Currey Publishers, 2006. ISBN 0-85255-995-X

- ^ Robert O. Collins. African History: Western African History, p. 153. Markus Wiener Publishers, 1990. ISBN 1-55876-015-6

- ^ "WIPSEN". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "WIPSEN EMPOWERS WOMEN…To fight for their rights" (article). Ghana Media Group. 11 December 2010.

- ^ November 2009 MEDIAGLOBAL

External links

- West Africa by Region and Country – African Studies at Columbia University

- ouestaf.com – Ouestaf, a West African online newspaper Template:Fr icon

- Loccidental – An online West African newspaper Template:Fr icon

- West Africa Review – An e-journal on West Africa research and scholarship Template:En icon

- The Voyage of the Sieur Le Maire, to the Canary Islands, Cape-Verde, Senegal, and Gambia is the first published writing about Western Africa, dating from 1695 Template:En icon

- [1]