Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. | |

|---|---|

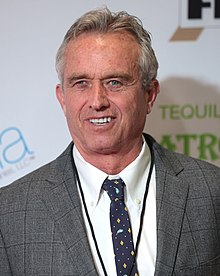

Kennedy in 2017 | |

| Born | Robert Francis Kennedy Jr. January 17, 1954 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education | Harvard University (AB) London School of Economics University of Virginia (JD) Pace University (LLM) |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Emily Black

(m. 1982; div. 1994) |

| Children | 6 |

| Parent(s) | Robert F. Kennedy Ethel Kennedy |

| Family | Kennedy |

Robert Francis Kennedy Jr. (born January 17, 1954) is an American environmental lawyer and author known for promoting anti-vaccine propaganda and conspiracy theories.[1][2][3] Kennedy is a son of U.S. senator Robert F. Kennedy and a nephew of President John F. Kennedy. He helped found the non-profit environmental group Waterkeeper Alliance in 1999 and has served as the president of its board. Kennedy has co-hosted Ring of Fire, a nationally syndicated radio program, and written or edited ten books, including two New York Times bestsellers.

From 1986 until 2017, Kennedy was a senior attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), a non-profit environmental organization. From 1984 until 2017, he was a board member and attorney for Hudson Riverkeeper.[4] Earlier in his legal career, he served as assistant district attorney in New York City. For over thirty years, Kennedy was an adjunct professor of Environmental law at Pace University School of Law. Until August 2017, he held the post as supervising attorney and co-director of Pace Law School's Environmental Litigation Clinic, which he founded in 1987.[5]

Since 2005, he has promoted the scientifically discredited idea that vaccines cause autism,[6] and is founder and chairman of Children's Health Defense, an anti-vaccine propaganda group.[7]

Early life and education

Kennedy was born at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., on January 17, 1954. He is the third of eleven children of senator and attorney general Robert F. Kennedy and Ethel Kennedy, née Skakel. He is a nephew of president and senator John F. Kennedy, and senator Ted Kennedy.

Kennedy grew up at his family's homes in McLean, Virginia, and Cape Cod, Massachusetts.[8] He was 9 years old in 1963 when his uncle, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated, and 14 years old in 1968 when his father was assassinated while running for president in the 1968 Democratic presidential primaries.

Kennedy learned of his father's shooting when he was at Georgetown Preparatory School, a Jesuit boarding school in North Bethesda, Maryland.[9] A few hours later, he flew to Los Angeles on vice-president Hubert Humphrey's plane, along with his elder sister Kathleen and elder brother Joseph, and was with his father when he died. Kennedy was a pallbearer in his father's funeral, where he spoke and read excerpts from his father's speeches at the Mass commemorating his death at Arlington National Cemetery.[10][11]

After obtaining his high school diploma from the Palfrey Street School in Massachusetts,[12] Kennedy continued his education at Harvard and the London School of Economics, graduating from Harvard College in 1976 with a Bachelor of Arts in American History and Literature. He went on to earn a Juris Doctor from the University of Virginia and a Master of Laws from Pace University.[13]

Career

In 1983, when Kennedy was an Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan,[citation needed] he was arrested and pled guilty to heroin possession and was sentenced to two years' probation and community service.[14][15] Following his arrest he entered a drug treatment center and during his probation volunteered for the Natural Resources Defense Council. His probation ended a year early.[16] In 1984, Kennedy joined Riverkeeper as an investigator, and was promoted to senior attorney[17] when he was admitted to the New York bar in 1985.[16]

Kennedy is an environmental law specialist and partner in the law firms of Morgan & Morgan and of Kennedy & Madonna, LLP,[18] and is an advocate for environmental justice.

Through litigation, lobbying, teaching, and public campaigns and activism, Kennedy has advocated for the protection of waterways, indigenous rights, and renewable energy.[19]

In 2018, the National Trial Lawyers Association awarded Kennedy and his trial team Trial Team of the Year for their work winning a $289 million jury verdict in Dewayne "Lee" Johnson v Monsanto.[20]

Riverkeeper

Kennedy litigated and supervised environmental enforcement lawsuits on the east coast estuaries on behalf of Hudson Riverkeeper and the Long Island Soundkeeper,[21] where he was also a board member. Long Island Soundkeeper brought numerous lawsuits against cities and industries along the Connecticut and New York coastlines.[22] In 1986, Kennedy won a landmark case against Remington Arms Trap and Skeet Gun Club in Stratford, Connecticut, that ended the practice of shooting lead shot into Long Island Sound.[23] Kennedy also filed federal lawsuits to close the Pelham Bay landfill and the New York Athletic clubs, arguing that those facilities were interfering with public use of Long Island Sound.[24] On the Hudson, Kennedy brought a series of lawsuits against municipalities, including New York City, to properly treat sewage, and against industries, including Consolidated Edison, General Electric and Exxon, to stop discharging pollution and to clean up legacy contamination.[25]

In 1995, Kennedy advocated for repeal of the anti-environmental legislation during the 104th Congress.[26] In 1997, Kennedy worked with John Cronin to write The Riverkeepers, a history of the early Riverkeepers and a primer for the Waterkeeper movement.[17]

Drawing on his experience investigating and suing polluters on behalf of the Waterkeepers, Kennedy has written extensively about environmental law enforcement.[27]

Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic

In 1987, Kennedy founded the Environmental Litigation Clinic at Pace University School of Law, where for three decades he was the clinic's supervising attorney and co-director, and as Clinical Professor of Law.[28] Kennedy obtained a special order from the New York State Court of Appeals that permitted his 10 clinic students–second- and third-year law students–to practice law and to try cases against Hudson River polluters in state and federal court, under the supervision of Kennedy and his co-director, Professor Karl Coplan. The clinic's full-time clients are Riverkeeper and Long Island Soundkeeper.[29]

The clinic has sued numerous governments and companies for polluting Long Island Sound and the Hudson River and its tributaries.[30] The clinic argued cases to expand citizen access to the shoreline and won hundreds of settlements for the Hudson Riverkeeper.[31] Kennedy and his students also sued dozens of municipal waste-water treatment plants to force compliance with the Clean Water Act.[29] In 2010, a Pace lawsuit forced ExxonMobil to clean up tens of millions of gallons of oil from legacy refinery spills in Newtown Creek in Brooklyn, New York.[32]

On April 11, 2001, Men's Journal recognized Kennedy with its "Heroes" Award for his creation of the Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic.[33] Kennedy and his Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic received other awards for successful legal work cleaning up the environment.[34] The Pace Clinic became a model for similar environmental law clinics throughout the country including Rutgers,[35] Golden Gate, UCLA,[36] Widener,[37] and Boalt Hall at Berkeley.[38]

Waterkeepers Alliance

In June 1999, as Riverkeeper's success on the Hudson began inspiring the creation of Waterkeepers across North America, Kennedy and a few dozen Riverkeepers gathered in Southampton, Long Island, to found the Waterkeeper Alliance, which is now the umbrella group for the 344 licensed Waterkeeper programs[39] located in 44 countries.[40] As President of the Alliance, Kennedy oversees its legal, membership, policy and fundraising programs. The Alliance states that it is dedicated to promoting "swimmable, fishable, drinkable waterways, worldwide,"[41] and is also a clearinghouse, approving new Keeper programs and licensing use of the trademarked "Waterkeeper," "Riverkeeper," "Soundkeeper," "Lakekeeper," "Baykeeper," "Bayoukeeper," "Canalkeeper," "Coastkeeper," etc. names.[42]

Kennedy and his environmental work have been the focus of several films including The Hudson Riverkeepers (1998)[43] and The Waterkeepers (2000),[44] both directed by Les Guthman. In 2008, he appeared in the IMAX documentary film Grand Canyon Adventure: River at Risk, riding the length of the Grand Canyon in a wooden dory with his daughter 'Kick' and with anthropologist Wade Davis.[45]

New York City Watershed Agreement

Beginning in 1991, Kennedy represented environmentalists and New York City watershed consumers in a series of lawsuits against New York City and upstate watershed polluters. Kennedy authored a series of articles and reports[46][47][48] alleging that New York State was abdicating its responsibility to protect the water repository and supply. In 1996, he helped orchestrate the $1.2 billion New York City Watershed Agreement, which New York magazine recognized in its cover story, "The Kennedy Who Matters".[49] This agreement, which Kennedy negotiated on behalf of environmentalists and New York City watershed consumers, is regarded as an international model in stakeholder consensus negotiations and sustainable development.[50]

Kennedy & Madonna LLP

In 2000, Kennedy and environmental lawyer Kevin Madonna founded the environmental law firm Kennedy & Madonna, LLP, to represent private plaintiffs against polluters.[51] The firm litigates environmental contamination cases on behalf of individuals, non-profit organizations, school districts, public water suppliers, Indian tribes, municipalities and states. In 2001, Kennedy & Madonna organized a team of prestigious plaintiff law firms to challenge pollution from industrial pork and poultry production.[52] In 2004, the firm was part of a legal team that secured a $70 million settlement for property owners in Pensacola, Florida whose properties were contaminated by chemicals from an adjacent Superfund site.[53]

Kennedy & Madonna is profiled in the 2010 HBO documentary Mann v. Ford[54] that chronicles four years of litigation brought by the firm on behalf of the Ramapough Mountain Indian Tribe against the Ford Motor Company over the dumping of toxic waste on tribal lands in northern New Jersey.[55] In addition to a monetary settlement for the tribe, the lawsuit contributed to the community's land being re-listed on the federal Superfund list, the first time in the nation's history that a de-listed site was re-listed.[56] In 2007 Kennedy was one of three finalists nominated as "Trial Lawyer of the Year" by Public Justice for his role in the $396 million jury verdict against DuPont for contamination from its Spelter, West Virginia zinc plant.[57] In 2017, the firm was part of the trial team that secured a $670 million settlement on behalf of over 3,000 residents from Ohio and West Virginia whose drinking water was contaminated with the toxic chemical, C8, which was released into the environment by DuPont in Parkersburg, West Virginia.[58]

Morgan & Morgan

In 2016, Kennedy became counsel to the Morgan & Morgan law firm.[59] The partnership arose from the two firms' successful collaboration on the case against SoCalGas Company following the Aliso Canyon gas leak in California.[60] In 2017, Kennedy and his partners sued Monsanto in federal court in San Francisco, on behalf of plaintiffs seeking to recover damages for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, that, the plaintiffs allege, were a result of exposure to Monsanto's glyphosate-based herbicide, Roundup. Kennedy and his team also filed a class action lawsuit against Monsanto for failing to warn consumers about the dangers allegedly posed by exposure to Roundup.[61] In September 2018, Kennedy and his partners filed a class-action lawsuit against Columbia Gas of Massachusetts alleging negligence following gas explosions in three towns north of Boston. Of Columbia Gas, Kennedy said "as they build new miles of pipe, the same company is ignoring its existing infrastructure, which we now know is eroding and is dilapidated."[62]

Cleantech and renewable energy infrastructure entrepreneurship

In 1998, Kennedy, Chris Bartle and John Hoving created a bottled-water company, Keeper Springs, which donated all of its profits to Waterkeeper Alliance.[63] In 2013, Kennedy and his partner sold the brand to Nestlé in exchange for a donation to local Waterkeepers.[64]

Kennedy was a venture partner and senior advisor at VantagePoint Capital Partners, one of the world's largest cleantech venture capital firms. Among other activities, VantagePoint was the original and largest pre-IPO institutional investor in Tesla. VantagePoint also backed BrightSource Energy and Solazyme, amongst others. Kennedy is a board member and counselor to several of Vantage Point's portfolio companies in the water and energy space, including Ostara, a Vancouver-based company that markets the technology to remove phosphorus and other excessive nutrients from wastewater, transforming otherwise pollution directly into high-grade fertilizer.[65] He is also a senior advisor to Starwood Energy Group and has played a key role in a number of the firm's investments.[66]

He is on the board of Vionx, a Massachusetts-based utility scale vanadium flow battery systems manufacturer. On October 5, 2017, Vionx, National Grid and the US Department of Energy completed the installation of advanced flow batteries at Holy Name High School in the city of Worcester, Massachusetts. The collaboration also includes Siemens and the United Technologies Research Center and constitutes one of the largest energy storage facilities in Massachusetts.[67]

Kennedy is a Partner in ColorZen, which offers a turnkey cotton fiber pre-treatment solution that reduces water usage and toxic discharges in the cotton dyeing process.[68]

Kennedy was a co-owner and Director of the smart grid company Utility Integration Solutions (UISol),[69] which was acquired by Alstom. He is presently a co-owner and Director of GridBright, the market-leading grid management specialist.[70]

In October 2011, Kennedy co-founded EcoWatch, an environmental news site. He resigned from the board of directors in January 2018.[71]

Minority and poor communities

In his first case as an environmental attorney, Kennedy represented the NAACP in a lawsuit against a proposal to build a garbage transfer station in a minority neighborhood in Ossining, New York.[72]

In 1987, he successfully sued Westchester County, New York, to reopen the Croton Point Park, which was heavily used primarily by poor and minority communities from the Bronx.[73] He then forced the reopening of the Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, which New York City had closed to the public and converted to a police firing range.[17]

Kennedy has argued that poor communities shoulder the disproportionate burden of environmental pollution.[74] Speaking at the 2016 SXSW Eco environment conference in Austin, Texas, he said, "Polluters always choose the soft target of poverty", noting that Chicago's south side has the highest concentration of toxic waste dumps in America.[75] Furthermore, he added that 80 percent of "uncontrolled toxic waste dumps" can be found in black neighborhoods, with the largest site in the United States being in Emelle, Alabama, which is 90 percent black.[76]

International and indigenous rights

Starting in 1985, Kennedy helped develop the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)'s international program for environmental, energy, and human rights, traveling to Canada and Latin America to assist indigenous tribes in protecting their homelands and opposing large-scale energy and extractive projects in remote wilderness areas.[77]

In 1990, Kennedy assisted indigenous Pehuenches in Chile in a partially successful campaign to stop the construction of a series of dams on Chile's iconic Biobío River. That campaign derailed all but one of the proposed dams.[78] Beginning in 1992, he assisted the Cree Indians of northern Quebec in their campaign against Hydro-Québec to halt construction of some 600 proposed dams on eleven rivers in James Bay.[79]

In 1993, Kennedy and NRDC, working with the indigenous rights organization Cultural Survival, clashed with other American environmental groups in a dispute about the rights of Indians to govern their own lands in the Oriente region of Ecuador.[80] Kennedy represented the CONFENIAE, a confederation of Indian peoples, in negotiation with the American oil company Conoco to limit oil development in Ecuadorian Amazon and, at the same time, obtain benefits from resource extraction for Amazonian tribes.[80] Kennedy was a vocal critic of Texaco for its previous record for polluting the Ecuadoran Amazon.[81]

From 1993 to 1999, Kennedy worked with five Vancouver Island Indian tribes in their campaign to end industrial logging by MacMillan Bloedel in Clayoquot Sound, British Columbia.[82]

In 1996, Kennedy met with Cuban President Fidel Castro to persuade the leader to halt his plans to construct a nuclear power plant at Juraguá.[83] During a lengthy latenight encounter, Castro reminisced about Kennedy's father and uncle, speculating that U.S. relations with Cuba would have been far better had President Kennedy not been assassinated.[84]

Between 1996 and 2000, Kennedy and NRDC helped Mexican commercial fishermen to halt Mitsubishi's proposal to build a salt facility in the Laguna San Ignacio, a known area in Baja where gray whales bred, and nursed their calves.[85] Kennedy wrote extensively against the project, and took the campaign to Japan, meeting with the Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi.[86]

In 2000, he assisted local environmental activists to stop proposals by Chaffin Light, a real estate developer, and U.S. engineering giant Bechtel from building a large hotel and resort development that, Kennedy argued, threatened coral reefs and public beaches used extensively by local Bahamians, at Clifton Bay, New Providence Island.[87] Following this, the new Bahamian government designated the area a Heritage Park.[citation needed]

Kennedy was one of the early editors of Indian Country Today, North America's largest Native American newspaper.[88] He helped lead the opposition to the damming of the Futaleufú River in the Patagonia region of Chile.[89] In 2016, citing the pressure precipitated by the Futaleufú Riverkeeper's campaign against the dams, the Spanish power company, Endesa, which owned the right to dam the river, reversed its decision and relinquished all claims to the Futaleufú.[90]

Military and Vieques

Kennedy has been a critic of environmental damage by the U.S. military.[91][92] In 1993, he successfully represented the Suquamish and Duwamish Indian tribes in a lawsuit against the U.S. Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, to stop polluting Puget Sound.[93]

In a 2001 article, Kennedy described how he sued the U.S. Navy on behalf of fishermen and residents of Vieques, an island off Puerto Rico, to stop weapons testing, bombing, and other military exercises. Kennedy argued that the activities were unnecessary, and that the Navy had illegally destroyed several endangered species, polluted the island's waters, harmed the residents' health, and damaged its economy.[94] He was arrested for trespassing at Camp Garcia Vieques, the U.S. Navy training facility, where he and others were protesting the use of a section of the island for training. Kennedy served 30 days in a maximum security prison in Puerto Rico.[95] The trespassing incident forced the suspension of live-fire exercises for almost three hours.[96] The lawsuits and protests by Kennedy, and hundreds of Puerto Ricans who were also imprisoned, eventually forced the termination of naval bombing in Vieques by president George Bush.[97]

In a 2003 article for the Chicago Tribune, Kennedy accused the U.S. federal government of being "America's biggest polluter" and the U.S. Department of Defense as the worst offender. Citing the EPA, he said that "unexploded ordnance waste can be found on 16,000 military ranges...and more than half may contain biological or chemical weapons".[98]

Factory farms

For almost twenty years, Kennedy and his Waterkeepers waged a legal and public relations battle against pollution by factory farms. In the 1990s, he rallied opposition to factory farms among small independent farmers, convened a series of "National Summits" on factory meat products, and conducted press conference whistle stop tours across North Carolina, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Ohio and in Washington DC. Beginning in 2000, Kennedy sued factory farms in North Carolina, Oklahoma, Maryland, and Iowa.[99] He wrote numerous articles on the subject, arguing that factory farms produce lower-quality, less healthy food, and are harmful to independent family farmers by poisoning their air and water, reducing their property values, and using extensive state and federal subsidies to impose unfair competition against smaller farmers.[100]

In 1995, Premier Ralph Klein of Alberta declared Kennedy persona non grata in the province due to Kennedy's activism against Alberta's large-scale hog production facilities.[101] In 2002, Smithfield Foods filed a lawsuit against Kennedy in Poland, under a Polish law that makes criticizing a corporation illegal, after Kennedy denounced the company in a debate with Smithfield's Polish director before the Polish parliament.[99]

Oil, gas, and pipelines

Kennedy has been an advocate for a global transition away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy.[102][103] He has been particularly critical of the oil industry. He began his career at Riverkeeper during the time that the organization discovered that Exxon was using its oil tankers in order to steal fresh water from the Hudson River for use in its Aruba refinery and to sell to Caribbean Islands. Riverkeeper won a $2 million settlement against Exxon and lobbied successfully for a state law outlawing the practice.[104] In one of his first environmental cases, Kennedy filed a lawsuit against Mobil Oil for polluting the Hudson.[105]

Kennedy helped lead the battle against fracking in New York State.[106] He had been an early supporter of natural gas as viable bridge fuel to renewables, and a cleaner alternative to coal.[107] However, he said he turned against this controversial extraction method after investigating its cost to public health; climate and road infrastructure.[108] As a member of Governor Andrew Cuomo's fracking commission, Kennedy helped engineer the Governor's 2013 ban on fracking in New York State.[109]

Kennedy mounted a national effort against the construction of liquefied natural gas facilities.[110] Waterkeepers maintains a national watch that documents numerous crude oil spills annually. In Alaska, Kennedy was active in the fight to save the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), the largest undisturbed ecosystem in North America, from drilling.[citation needed]

In 2013, Kennedy assisted the Chipewyan First Nation and the Beaver Lake Cree fighting to protect their land from tar sands production.[111] In February 2013, while protesting the Keystone XL Pipeline Kennedy, along with his son, Conor, was arrested for blocking a thoroughfare in front of the White House during a protest.[112] In August 2016, Kennedy and Waterkeeper participated in protests to block the extension of the Dakota Access pipeline across the Sioux Indian Standing Rock Reservation's water supply.[113]

Kennedy claims that the only reason the oil industry is able to remain competitive against renewables and electric cars is through massive direct and indirect subsidies and political interventions on behalf of the oil industry. In a June 2017 interview on EnviroNews, Kennedy said about the oil industry, "That's what their strategy is: build as many miles of pipeline as possible. And what the industry is trying to do is to increase that level of infrastructure investment so our country won't be able to walk away from it.[114]

Coal

Under Kennedy's leadership, Waterkeeper launched its "Clean Coal is a Deadly Lie"[115] campaign in 2001, bringing dozens of lawsuits targeting mining practices, which include mountaintop removal,[116] slurry pond construction, and targeting mercury emissions and coal ash piles by coal-burning utilities.[117] Kennedy's Waterkeeper alliance has also been leading the fight against coal export, including from terminals in the Pacific Northwest.[118]

Kennedy has promoted replacing coal energy with renewable energy, which, he argues, would thereby reduce costs and greenhouse gases while improving air and water quality, the health of the citizens, and the number and quality of jobs.[119] In June 2011, film producer Bill Haney televised his award-winning film The Last Mountain, co-written by Haney and Peter Rhodes, depicting Kennedy's fight to stop Appalachian mountaintop removal mining.[120]

Nuclear power

Kennedy has been an opponent of conventional nuclear power, arguing that it is unsafe and not economically competitive.[121][122] On June 15, 1981, he made international news when he spoke at an anti-nuclear rally at the Hollywood Bowl, with Stephen Stills, Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne.[123]

His thirty-year battle to close Indian Point nuclear power plant in New York ended in victory in January 2017, when Kennedy signed onto an agreement with New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo and Entergy, the plant's operator, to close the plant by 2021.[124] Kennedy was featured in a 2004 documentary, Indian Point: Imagining the Unimaginable, directed by his sister and documentary filmmaker Rory Kennedy.[125]

Hydro

Kennedy has been an outspoken opponent of dams, particularly of dam projects that affect indigenous communities.

In 1991, Kennedy helped lead a campaign to block Hydro-Québec from building the James Bay Hydro-project, a massive dam project in northern Quebec.[126]

His campaigns helped block dams on Chile's Biobío River in 1990[127] and its Futaleufú River in 2016. In 2002, he mounted what was ultimately an unsuccessful battle against building a dam on Belize's Macal River. Kennedy termed the Chalillo Dam "a boondoggle", and brought a high-profile legal challenge against Fortis Inc., a Canadian power company and the monopoly owner of Belize's electric utility.[128] In a 3–2 ruling in 2003, the Privy Council of the United Kingdom upheld the Belizean government's decision to permit dam construction.[128][129][130]

In 2004, Kennedy met with Provincial officials and brought foreign media and political visitors to Canada to protest the building of hydroelectric dams on Quebec's Magpie River.[131] Hydro-Quebec dropped plans for the dam in 2017.[132]

In November 2017, the Spanish hydroelectric syndicate Endesa decided to abandon HydroAysen, a massive project to construct dams on dozens of Patagonia's rivers accompanied by thousands of miles of roads, power lines and other infrastructure. Endesa returned its water rights to the Chilean government. The Chilean press credits advocacy by Kennedy and Riverkeeper as critical factors in the company's decision.[133]

Cape Wind

In 2005, Kennedy clashed with national environmental groups over his opposition to the Cape Wind Project, a proposed offshore wind farm off of the coast of Cape Cod in Nantucket Sound. Taking the side of Cape Cod's commercial fishing industry, Kennedy argued that the project was a costly boondoggle. This position angered some environmentalists, and brought Kennedy criticism by industry groups and Republicans[who?].[134] Kennedy argued in an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal that "Vermont wants to take its nuclear plant off line and replace it with clean, green power from HydroQuébec — power available to Massachusetts utilities — at a cost of six cents per kilowatt hour (kwh). Cape Wind electricity, by a conservative estimate and based on figures they filed with the state, comes in at 25 cents per kwh."[135]

Political views

Criticisms

Throughout the presidency of George W. Bush, Kennedy was a persistent critic of Bush's environmental and energy policies. He accused Bush of defunding and corrupting federal science projects.[136]

Kennedy was also critical of Bush's 2003 hydrogen car initiative,[137] arguing that it was a gift to the fossil fuel industry disguised as a green automobile.[138]

In 2003, Kennedy wrote an article in Rolling Stone about Bush's environmental record,[139] which he subsequently expanded into a New York Times bestselling book.[140] His opposition to the environmental policies of the Bush administration earned him recognition as one of Rolling Stone's "100 Agents of Change" on April 2, 2009.[141][142]

During an October 2012 interview with Politico, Kennedy called on environmentalists to direct their dissatisfaction towards the U.S. Congress rather than President Barack Obama, reasoning that Obama "didn't deliver" due to having a partisan U.S. Congress "like we haven't seen before in American history".[143] He also accused politicians who failed to act on climate change policy as serving special interests and, selling out the public trust. He accused Charles and David Koch, the owners of Koch Industries, Inc., the nation's largest privately owned oil company, of subverting democracy and for "making themselves billionaires by impoverishing the rest of us".[144] Kennedy has spoken of the Koch Brothers as leading "the apocalyptical forces of Ignorance and Greed".[145]

During the 2014 People's Climate March, Kennedy said, "American politics is driven by two forces: One is intensity, and the other is money. The Koch brothers have all the money. They're putting $300 million this year into their efforts to stop the climate bill. And the only thing we have in our power is people power, and that's why we need to put this demonstration on the street".[146]

U.S. foreign policy

Kennedy has written extensively on foreign policy, beginning with a 1974 Atlantic Monthly article titled, "Poor Chile", discussing the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende.[147] Kennedy also wrote editorials against the execution of Pakistan President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto by General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq.[148][149] In 1975, he published an article in The Wall Street Journal, criticizing the use of assassination as a foreign policy tool.[150] In 2005, he wrote an article for the Los Angeles Times decrying President Bush's use of torture as anti-American.[151] Senator Edward Kennedy entered the article into the Congressional Record.[152]

In an article titled "Why the Arabs Don't Want Us in Syria", published in Politico in February 2016, Kennedy referred to the "bloody history that modern interventionists like George W. Bush, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio miss when they recite their narcissistic trope that Mideast nationalists 'hate us for our freedoms.' For the most part they don't; instead they hate us for the way we betrayed those freedoms — our own ideals — within their borders".[153] Kennedy blames the Syrian war on a pipeline dispute. He cites apparent WikiLeaks disclosures alleging that the CIA-led military and intelligence planners to foment a Sunni uprising against Syria's president, Bashar al-Assad, following his rejection of a proposed Qatar-Turkey pipeline through Syria in 2009, well before the Arab Spring.[154]

Political endorsements

Kennedy was on the National Staff and a State Coordinator for Edward M. Kennedy for President from 1979 to 1980. Prior to that he had been on Senator Kennedy's 1970 and 1976 Massachusetts senatorial campaigns. He was a co-founder and a former board member of the New York League of Conservation Voters.[155][156]

Kennedy endorsed and campaigned extensively for Vice President Al Gore during his 2000 presidential campaign, and openly opposed his friend Ralph Nader's Green Party presidential campaign. In the 2004 presidential election, Kennedy endorsed John Kerry, noting his strong environmental record.[157]

In late 2007, Kennedy and his sisters Kerry and Kathleen endorsed Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic Party presidential primaries.[158] After the Democratic Convention, Kennedy campaigned for Obama across the country.[159] After the election, he was named as a front-runner for Obama's EPA administrator.[160]

Kennedy has been critical of the integrity of the voting process. In June 2006, he published an article in Rolling Stone purporting to show that GOP operatives stole the 2004 presidential election for President George W. Bush. Farhad Manjoo countered Kennedy's conclusions,[161] but there were other people who argued otherwise.[162]

Kennedy has written frequent warnings about the ease of election hacking and the dangers of voter purges and voter ID laws. He wrote the introduction and a chapter in Billionaires and Ballot Bandits, a 2012 book on election hacking by the investigative journalist Greg Palast.[163]

Political aspirations

Kennedy first considered running for political office in 2000, when New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan did not seek re-election to the U.S. Senate seat formerly held by Kennedy's father.[164] His father was elected to the same seat in 1964, and held it for 41 months, until his death in 1968.

In 2005, Kennedy considered running for New York Attorney General, which would have meant a possible run against his then brother-in-law Andrew Cuomo, but in the end he decided against entering the race, even though he had been considered the frontrunner.[165]

On December 2, 2008, Kennedy stated that he did not wish to be appointed to the U.S. Senate by New York Governor David Paterson. He felt that it would take too much time away from his family.[166]

Personal opinions

Food allergies

Kennedy was a founding board member of the Food Allergy Initiative. His son suffers from anaphylactic peanut allergies. Kennedy wrote the foreword to The Peanut Allergy Epidemic, in which he and the authors falsely link increasing food allergies in children to certain vaccines that were approved beginning in 1989.[167][7]

Autism and vaccines

Kennedy is the chairman of Children's Health Defense (formerly the World Mercury Project), an advocacy group he founded in 2016.[7] The group alleges a large proportion of American children are suffering from conditions as diverse as autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, food allergies, cancer, and autoimmune diseases due to exposure to certain chemicals and radiation. The Children's Health Defense has blamed and campaigned against vaccines, fluoridation of drinking water, paracetamol (acetaminophen), aluminum, wireless communications, and others. Kennedy's group has been identified as one of two major buyers of anti-vaccine Facebook advertising in late 2018 and early 2019.[168][169][7]

In its early years, the group focused on the perceived issue of mercury in industry and medicine, especially the ethylmercury compound thimerosal in vaccines, proposed by the discredited former doctor Andrew Wakefield as a mechanism for the disproved link between vaccines and autism.[170][171] Other members of his family have criticized Kennedy and his organization, saying he spreads "dangerous misinformation" and said his work has "heartbreaking" consequences.[172]

According to the Center for Countering Digital Hate, Kennedy leverages his status as a prominent activist for environmental causes to bolster other actors of the anti-vaccination movement, regularly appearing in online conversations with the likes of Wakefield, Del Bigtree, Rashid Buttar.[173] Kennedy has stated the media and governments are engaged in a conspiracy to deny that vaccines cause autism.[174][175][176][177] The Center for Countering Digital Hate in 2021 identified Kennedy as one of 12 people responsible for up to 65% of anti-vaccine content on social media platforms Facebook and Twitter.[178]

In June 2005, Kennedy wrote an article in Rolling Stone and Salon called "Deadly Immunity", alleging a government conspiracy to conceal a connection between thimerosal and the epidemic of childhood neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism.[179] The article contained five factual errors, leading Salon to issue corrections.[180] Six years later Salon retracted the article completely.[180] According to Salon, the retraction was motivated by accumulating evidence of alleged errors and scientific fraud underlying the vaccine-autism claim.[181] A corrected version of the original article can still be found on the Rolling Stone website.[179]

In May 2013, Kennedy delivered the keynote address at the anti-vaccination[182] AutismOne / Generation Rescue conference.[183][184]

In 2014, Kennedy's book, Thimerosal: Let the Science Speak: The Evidence Supporting the Immediate Removal of Mercury—a Known Neurotoxin—from Vaccines, was published. While methylmercury is a potent neurotoxin, ethylmercury, as used in vaccine preservatives, is safer.[185] The preface to the book is written by Mark Hyman, a proponent of the alternative medical treatment called functional medicine.[186] Kennedy has published many articles on the inclusion of the mercury-based preservative thimerosal in vaccines.[187][188][189][190]

In April 2015, Kennedy participated in a Speakers' Forum to promote the film Trace Amounts, which promotes the link between autism and mercury in vaccinations. At a film screening, Kennedy described the autism epidemic as a "holocaust".[191]

On January 10, 2017, incoming White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer confirmed that Kennedy and President-elect Donald Trump met to discuss a position in the Trump administration. Kennedy accepted an offer made by Trump to become the chairman of the Vaccine Safety Task Force. A spokeswoman for Trump's transition said that no final decision had been made.[192] In an August 2017 interview with STAT News reporter Helen Branswell, Kennedy said that he had been meeting with the federal public health regulators to discuss defects in vaccine safety science, at the White House's request.[193]

On February 15, 2017, Kennedy and actor Robert De Niro gave a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in which they accused the press of acting as propagandists for the $35 billion vaccination industry and refusing to allow debates on vaccination science. They offered a $100,000 reward to any journalist or other citizen who could point to a study showing that it is safe to inject mercury into babies and pregnant women at levels currently contained in flu vaccines. Craig Foster, a psychology professor who studies pseudoscience, deemed the challenge "not science", observing that it was a "carefully constructed 'contest' that allows its creators to generate the misleading outcome they presumably want to see". He also stated that "Proving that something is safe is importantly different than proving that something is harmful".[194]

Several members from his close family have distanced themselves from his anti-vaccination activities and condemned Kennedy's comments equating public health measures with nazi atrocities.[195] On May 8, 2019, Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Joseph P. Kennedy and Maeve Kennedy McKean wrote an open letter stating that while their relative has championed many admirable causes, he "has helped to spread dangerous misinformation over social media and is complicit in sowing distrust of the science behind vaccines".[196] On December 30, 2020, Kennedy's niece Kerry Kennedy Meltzer, a physician, wrote a similar open letter. She argued her uncle published misinformation about the side effects of the new COVID-19 vaccines.[197]

On June 4, 2019, during a visit to Samoa coinciding with that nation's 57th annual independence celebration, Kennedy appeared in an Instagram photo with Australian-Samoan anti-vaccine activist Taylor Winterstein. Kennedy's charity and Winterstein have both perpetuated the allegation that the MMR vaccine played a role in the 2018 deaths of two Samoan infants, despite the subsequent revelation that the infants had received a muscle relaxant along with the vaccine by mistake. Kennedy has drawn criticism for fueling vaccine hesitancy amid a social climate which gave rise to the 2019 Samoa measles outbreak, which killed over 70 people, and the 2019 Tonga measles outbreak.[198][199] On February 11, 2021, his Instagram account was permanently deleted "for repeatedly sharing debunked claims" about COVID-19 vaccines.[200][201]

Kennedy is listed as executive producer of Vaxxed II: The People's Truth, the 2019 sequel to Wakefield's and Bigtree's anti-vaccination documentary Vaxxed.[202]

Similar to many who share his beliefs, Kennedy has claimed that he is not against vaccines but wishes that they be more thoroughly tested and investigated.[203][204]

In early March 2021, Kennedy's anti-vaccine organization, Children's Health Defense released a new anti-vaccine propaganda video, "Medical Racism: The New Apartheid" that promotes COVID-19 conspiracy theories and claims that COVID-19 vaccination efforts are medical experiments on the Black community. Kennedy himself appears in the video, inviting the viewers to disregard information dispensed by health authorities and doctors. Brandi Collin-Dexter, a Fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy states "the notorious figures and false narratives in the documentary were recognizable" and that "the film's incompatible narratives sought to take advantage of the pain felt by Black communities".[205][206][207]

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kennedy promoted multiple conspiracy theories related to COVID-19 including false claims both Anthony Fauci and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are trying to profit off a vaccine,[208][209][210] and suggesting that Bill Gates would cut off access to money of people who do not get vaccinated, allowing them to starve.[211] In August 2020, Kennedy appeared in an hour-long interview with Alec Baldwin on Instagram, where he touted a number of incorrect and misleading claims about vaccines and public health measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Baldwin was criticized by public health officials and scientists for allowing Kennedy's proclamations to go unchallenged.[212] Kennedy has promoted misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine, falsely suggesting that it contributed to the death of 86-year-old Hank Aaron and others.[213][214][7] In February 2021 his Instagram account was blocked for "repeatedly sharing debunked claims about the coronavirus or vaccines."[215][216] The Center for Countering Digital Hate identified Kennedy as one of the main propagators of conspiracy theories about Bill Gates and 5G phone technology. His success as a conspiracy theorist increased his social media impact considerably; between the Spring and the Fall of 2020, his Instagram account grew from 121,000 followers to 454,000.[173][217]

In November 2021, Kennedy's book The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health was published wherein he alleges Fauci sabotaged treatments for AIDS, violated federal laws, and conspired with Bill Gates and social media companies such as Facebook to suppress any information about COVID-19 cures, to leave vaccines as the only options to fight the pandemic.[218][219] In the book, Kennedy calls Fauci "a powerful technocrat who orchestrated and executed the historic 2020 coup against Western democracy". He claims Fauci and Bill Gates plan to prolong the pandemic and exaggerate its effects, promoting expensive vaccinations for the benefit of "a powerful vaccination cartel".[220] The book repeats several discredited myths about the COVID-19 pandemic, notably about the effectiveness of ivermectin.[221] The Neue Zürcher Zeitung has said of the book "…polemics alternate with chapters that pedantically seek to substantiate Kennedy's accusations with numerous quotations and studies."[220] He also released a video depicting Fauci with a Hitler moustache.[222] In response to the book, Fauci called Kennedy "a very disturbed individual."[223]

Kennedy wrote the foreword for Plague of Corruption (2020), a book by former research scientist and anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist Judy Mikovits.[7]

Kennedy appeared as a speaker at the partially violent demonstration in Berlin on August 29, 2020, where populist groups called for an end to restrictions caused by COVID-19.[224][225] His YouTube account was removed in late September 2021 for breaking the company's new policies on vaccine misinformation.[226]

In a January 23, 2022, speech at an anti-vaccination rally in Washington D.C., Kennedy said: "Even in Hitler's Germany, you could cross the Alps into Switzerland, you can hide in the attic like Anne Frank did…Today the mechanisms are being put in place that will make it so none of us can run, none of us can hide."[227] The Auschwitz Memorial stated on Twitter: "Exploiting of the tragedy of people who suffered, were humiliated, tortured & murdered by the totalitarian regime of Nazi Germany - including children like Anne Frank - in a debate about vaccines & limitations during global pandemic is a sad symptom of moral & intellectual decay."[228] Two days later, Kennedy apologized for his comment.[222]

Views on the murder of Martha Moxley

In January 2003, Kennedy wrote a controversial article in The Atlantic Monthly about the 1975 murder of Martha Moxley in Greenwich, Connecticut, in which he insists that his cousin Michael Skakel's indictment "was triggered by an inflamed media, and that an innocent man is now in prison." The article argues that there is more evidence suggesting that Kenneth Littleton, the Skakel family's live-in tutor, killed Moxley. He also calls Dominick Dunne the "driving force" behind Skakel's prosecution.[229] In July 2016, Kennedy released a book titled Framed: Why Michael Skakel Spent over a Decade in Prison for a Murder He Didn't Commit.[230] In 2017, the rights to Kennedy's book were optioned by FX Productions to develop a multi-part television series.[231]

Views on JFK and RFK assassinations

On the evening of January 11, 2013, Charlie Rose interviewed Kennedy and his sister Rory at the Winspear Opera House in Dallas as a part of then Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings' hand-chosen committee's yearlong program of celebrating the life and presidency of John F. Kennedy.[232] On the assassination of John F. Kennedy, he said his father was "fairly convinced" Lee Harvey Oswald had not acted alone and privately believed the Warren Commission report was a "shoddy piece of craftsmanship". According to Robert F. Kennedy, Jr in January 2013: "The evidence at this point I think is very, very convincing that it was not a lone gunman".[233] The 2013 edition of JFK and the Unspeakable was endorsed by Kennedy, who said it had moved him to visit Dealey Plaza, the site of his uncle's assassination, for the first time.[234]

Kennedy does not believe Sirhan Sirhan was responsible for the assassination of his father, Robert F. Kennedy, and visited the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility, San Diego, in December 2017 to meet Sirhan.[235] After meeting Sirhan, he came to the conclusion there was a second gunman and gave his support for a reinvestigation of the assassination.[235]

Personal life

General interests

Kennedy is a licensed master falconer and has trained hawks since he was 11. He breeds hawks and falcons and is also licensed as a raptor propagator and a wildlife rehabilitator.[236] He holds permits for Federal Game Keeper, Bird Bander, and Scientific Collector. He was President of the New York State Falconry Association from 1988 to 1991. In 1987, while on Governor Mario Cuomo's New York State Falconry Advising Committee, Kennedy authored the examination to qualify apprentice falconers given by New York State. Later that year he wrote the New York State Apprentice Falconer's Manual, which was published by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, and continues in use today.[237]

Kennedy is also a whitewater kayaker. His father introduced him and his siblings to whitewater kayaking during early trips down the Green and Yampa Rivers in Utah and Colorado, the Columbia River, the Middle Fork Salmon in Idaho, and the Upper Hudson Gorge. From 1976 to 1981, Kennedy was a partner and guide at a whitewater company, "Utopian", based in West Forks, Maine. He organized and led several "first-descent" whitewater expeditions to Latin America including three hitherto unexplored rivers: the Apurimac, Peru, in 1975; the Atrato, Colombia, in 1979; and the Caroni, Venezuela, in 1982.[238] He made an early descent of Great Whale River in Northern Quebec, in 1993,[239] and has made many trips to Patagonia, Chile, to run the Biobío River, the Futaleufú and other whitewater rivers.

In 2015, he took two of his sons to the Yukon to visit Mount Kennedy and run the Alsek River, a whitewater river fed by the Alsek Glacier. Mount Kennedy had been Canada's highest unclimbed peak, when the Canadian Government named it for the assassinated American president, in 1964.[240] In 1965, his father Robert F. Kennedy was the first person to climb Mount Kennedy.[241]

Marriages and children

On April 3, 1982, Kennedy married Emily Ruth Black (born 1957), whom he had met at the University of Virginia School of Law.[242] They had two children: Robert Francis "Bobby" Kennedy III (born 1984; married to writer, peace activist and former CIA officer Amaryllis Fox) and Kathleen Alexandra ('Kick') Kennedy (born 1988).[243] The latter shares the nickname of her great-aunt, the late Kathleen Cavendish, Marchioness of Hartington.[244]

The couple separated in 1992 and divorced in 1994.[245]

On April 15, 1994, Kennedy married Mary Kathleen Richardson (1959–2012) aboard a research vessel on the Hudson River.[246] They had four children: Conor Richardson Kennedy (born 1994), Kyra LeMoyne Kennedy (born 1995), William Finbar "Finn" Kennedy (born 1997), and Aidan Caohman Vieques Kennedy (born 2001). On May 12, 2010, Kennedy filed for divorce from Mary; three days later she was charged with drunk driving. On May 16, 2012, Mary was found dead in a building on the grounds of her home in Mount Kisco, New York. The Westchester County Medical Examiner ruled the death to be a suicide due to asphyxiation from hanging.[247]

Kennedy married his third wife, actress-director Cheryl Hines, on August 2, 2014, at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. They were introduced by Larry David, whose wife Hines played in the HBO series Curb Your Enthusiasm, and began dating in 2012.[248][249]

Health

In 2008, it was reported that Kennedy has spasmodic dysphonia, which causes his voice to quaver and makes speech difficult. It is a form of an involuntary movement disorder called dystonia that affects only the larynx.[250]

Selected works

Kennedy has authored books on subjects such as the environment, science, biography, and American heroes, including three bestsellers and three children's books.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1978). Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr.: A biography. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-12123-4.

- Cronin, John; Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1997). The Riverkeepers: Two Activists Fight to Reclaim Our Environment as a Basic Human Right. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0684839080.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2005). Crimes Against Nature: How George W. Bush and His Corporate Pals Are Plundering the Country and Highjacking Our Democracy. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-074687-2.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2014). Thimerosal: Let the Science Speak: The Evidence Supporting the Immediate Removal of Mercury–a Known Neurotoxin–from Vaccines. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1632206015.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2016). Framed: Why Michael Skakel Spent Over a Decade in Prison For a Murder He Didn't Commit. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781510701779.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2018). American Values: Lessons I Learned from My Family. Harper. ISBN 978-0060848347.

- Kennedy, Robert F., Jr; Russell, Dick (2020). Climate in Crisis: Who's Causing It, Who's Fighting It, and How We Can Reverse It Before It's Too Late. Hot Books. ISBN 978-1510760561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2021). The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781510766808.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2022). A Letter to Liberals: Censorship and COVID: An Attack on Science and American Ideals. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 1510775595.

- Leake, John; McCullough, Peter A.; Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2022). The Courage to Face COVID-19: Preventing Hospitalization and Death While Battling the Bio–Pharmaceutical Complex. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 9781510776807.

Children's books

- St. Francis of Assisi: A Life of Joy. Hyperion. 2004. ISBN 978-0-7868-1875-4.

- Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s American Heroes: The Story of Joshua Chamberlain and the American Civil War. New York: Hyperion. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4231-0771-2.

- Robert Smalls: The Boat Thief. New York: Hyperion. 2008. ISBN 978-1423108023.

Select awards and recognition

Over the course of his career, Kennedy has received numerous awards in his name and on behalf of organizations and causes that he has championed.

- 2018, The National Trial Lawyers, Mass Tort Trial Team of the Year - for "groundbreaking case of Dewayne "Lee" Johnson v. Monsanto Company"[20]

- 2017, Earth Justice Mountain Heroes[251]

- 2017, Foro La Region Award for "La Proteccion de los Recrsos Naturales"[252]

- 2014, Stroud Award of Freshwater Excellence[253]

- 2009, Rolling Stone "100 Agents of Change"[142]

- 2008, USC Dornsife Sustainability Champion Award[254]

- 2008, Theodre Gordon Flyfishers Conservation Award[255]

- 2007, Vanity Fair "The Green Team"[256]

- 2005, William O. Douglas Award, on behalf of the Waterkeeper Alliance[257]

- 2003, Professional Resource Award, NY State Council of Trout Unlimited[255]

- 2001, Distinguished Service Award presented at Pace Law School's 25th Anniversary[258]

- 2001, Men's Journal "Heroes" Award[259]

- 2000, 12th Annual Manhattan Award[260]

- 2000, Jacques Sartisky Peace Award[260]

- 2000, New York State Champion of the Environment[261]

- 1999, Time Magazine's "Heroes of the Planet"[142]

- 1998, William E. Ricker Resource Conservation Award[262]

- 1997, EPA Environmental Quality Award[260]

- 1997, The Brave 40 Award from NYC Department of Environmental Conservation[260]

- 1997, Thomas Berry Environmental Award, presented to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and the Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic[263]

- 1995, Green Star Award presented by the Environmental Action Coalition[263]

- 1991, Eleanor Roosevelt Val-Kill Award[264]

See also

- Bobby Kennedy – Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s father

- Deadly Immunity

- Environmental law

- Kennedy family

- Waterkeeper Alliance

- Vaccines and autism

References

- ^ Oshin, Olafimihan (January 23, 2022). "Auschwitz Memorial says RFK Jr. speech at anti-vaccine rally exploits Holocaust tragedy". TheHill. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

During a speech at the rally, Kennedy, a conspiracy theorist and prominent anti-vaxxer, warned of a massive surveillance network being created with satellites in space and 5G mobile networks collecting data.

- ^ "Cheryl Hines Blasts Husband RFK Jr. for Holocaust Remark". The Wrap. January 25, 2022. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

Cheryl Hines has publicly condemned a statement made by her husband Robert F. Kennedy Jr. at a rally on Sunday, in which the environmental lawyer and conspiracy theorist likened COVID regulations to the Holocaust.

- ^ "Guests urged to be vaccinated at anti-vaxxer Robert F Kennedy Jr's party". The Guardian. December 18, 2021. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

The younger Kennedy has campaigned on environmental issues but is also a leading vaccines conspiracy theorist and activist against shots including those approved to combat Covid-19, which has killed more than 805,000 in the US and more than 5.3 million worldwide.

- ^ Agee, J'nelle (March 18, 2017) "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Resigns From Riverkeeper". Spectrum News Archived October 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Steve (April 29, 2015). "RFK Jr. to address College of Law graduates". Nebraska Today. Archived October 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mnookin, Seth (January 11, 2017). "How Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Distorted Vaccine Science". Scientific American. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Weir, Keziah (May 13, 2021). "How Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Became the Anti-vaxxer Icon of America's Nightmares". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (2018). American Values: Lessons I Learned from My Family. HarperLuxe. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-0062845917.

- ^ "Oprah Talks to Bobby Kennedy Jr.". February 2007. O, The Oprah Magazine

- ^ Storrin, Matt. (June 7, 1969). "Folk Mass Honors RFK". Boston Globe. Archived September 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Robert Kennedy's Words Sung In Mass Marking Assassination". June 7, 1970. New York Times. Archived October 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oppenheimer, Jerry (2015). RFK Jr.: Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and the Dark Side of the Dream. St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 129–147. ISBN 978-1250096661.

- ^ The Backbone Cabinet – A Progressive Cabinet Roster Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, backbonecampaign.org

- ^ "Robert Kennedy Jr. Admits He Is Guilty In Possessing Heroin". The New York Times. February 18, 1984. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Mark Leibovich (June 25, 2006). "Another Kennedy Living Dangerously". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. and Perlez, Jane (June 4, 1985). "A Quiet Victory For Robert F. Kennedy Jr". The New York Times.Archived October 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Cronin, John; Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1997). The Riverkeepers: Two Activists Fight to Reclaim Our Environment as a Basic Human Right. New York: Scribner. p. 304. ISBN 0684839083.

- ^ Slansky, Dov (April 1, 2016). "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and Kevin J. Madonna Join Morgan & Morgan". PRWEB.

- ^ Little, Amanda (July 14, 2004). "An interview with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., environmental advocate and Bush basher". Grist.org. http://grist.org/article/griscom-kennedy/ Archived October 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Millican, Scott (March 4, 2019). "Ring of Fire's RFK Jr. Wins Award for Monsanto Trial". trofire.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- ^ "Our core mission: Environmental enforcement". 2016. Riverkeeper Journal.

- ^ Gordon, Maggie (April 2, 2014). "Soundkeeper sues state in Stamford boatyard battle Archived January 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". Stamford Advocate.

- ^ 777 F. Supp. 173 (1981) Connecticut Coastal Fisherman's Association v. Remington Arms Company, Inc. and E.I. Dupont DeNemours and Company. Civ. No. B-87-250 (EBB). United States District Court, D. Connecticut. September 11, 1991. Justia US Law.

- ^ Venezia, Todd (July 5, 2005). "Bx. Dump Poisoned, Killed Kids – Now City Must Pay: Residents". New York Post.

- ^ Navasky, Bruno (August 11, 2016). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. On The Environment, The Election, And A 'Dangerous' Donald Trump Archived November 1, 2019, at the Wayback Machine". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Werth, Barry (May 2, 2004). "Somewhere Down the Crazy River Archived January 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". Outside.

- ^ Worth, Robert (July 1, 2001). "Watershed Warrior". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic - Pace Law School". www.law.pace.edu. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Robert F. Jr., Solow, Steven P. (1993). "Environmental Litigation as Clinical Education: A Case Study". University of Oregon Journal of Environmental Law and Litigation Volume 8

- ^ "A conversation with the authors of 'The Riverkeepers: Two Activists Fight to Reclaim Our Environment as a Basic Human Right'". November 10, 1997. Charlie Rose.

- ^ Cronin, John and Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (July 26, 1997). "It's Our River – Let Us Get to It". The New York Times

- ^ Brown, Kim (July 8, 2004). "ExxonMobil Sued Over 55-Acre Oil Spill In Newtown Creek". Queens Chronicle.

- ^ Kaydo, Chad (April 13, 2001). "A Manly Awards Party for Men's Journal". BizBash.

- ^ Pace Environmental Litigation Clinic. "Clinic Awards". Pace Law.

- ^ Rutgers School of Law Environmental Law Clinic. "About this Organization". Justia Lawyers.

- ^ Environmental Law Courses and Clinics. UCLA Law.

- ^ Environmental Law Clinic. Widener Environmental Law Center. Widener Law.

- ^ Environmental Law Clinic. Berkeley Law.

- ^ Gallay, Paul. May 3, 2018. "China enlists local groups in environmental enforcement push". Waterkeeper.org.

- ^ Yaggi, Marc, Waterkeeper Alliance. August 2, 2018. "Let Our Rivers Run Free: A Global Look at How Dams are Destroying our Waterways". Waterkeeper Magazine

- ^ "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Honored at Water's Edge Gala". (2014). Stroudcenter.org.

- ^ Wilke, Chris (March 19, 2012) "The Clean Water Act – A Story of Activism and Change". Read the Dirt.

- ^ "The Hudson Riverkeepers (1998)". IMDb.

- ^ "The Waterkeepers (TV Movie 2000)". IMDb.

- ^ "Grand Canyon Adventure: River at Risk (2008)". IMDb.

- ^ Gordon, David K. and Kennedy, Jr., Robert F. (September 1991). "The Legend of City Water: Recommendations For Rescuing the New York City Water Supply". The Hudson Riverkeeper Fund.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (August 22, 1989). "New York City's Water: Down the Drain". The New York Times.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Wechsler, Pat (November 27, 1995). "The Kennedy Who Matters". New York Magazine.

- ^ Schneeweiss, Jonathan (1997). "Watershed Protection Strategies: A Case Study of the New York City Watershed in Light of the 1996 Amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act". 8 Vill. Environmental Law Journal 77.

- ^ "Team". Kennedy & Madonna, LLP. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "Farmers Worried by Suits Targeting Hog Producers". January 7, 2001. Des Moines Register. P.9.

- ^ "ConocoPhillips agrees to $70M settlement for former Fla. facility". April 7, 2004, EENews.net.

- ^ "Mann v. Ford" Archived March 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine (2010). IMDb.

- ^ "Mann v. Ford: Synopsis". HBO. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Strunsky, Steve (October 14, 2006). "Superfund Site Is Relisted, and Inquiry Begins Archived January 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". New York Times.

- ^ "DuPont Fined $196.2M In Class-Action Suit". October 19, 2007. CBSNews.com.

- ^ Rinehart, Earl (February 13, 2017). "DuPont to pay $670 million to settle C8 lawsuits". The Columbus Dispatch.

- ^ "Attorney Robert F. Kennedy, Jr". Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- ^ Cruz, Nancy (February 18, 2016) "Porter Ranch Gas Leak With Attorney Robert F. Kennedy". KTLA5.

- ^ Stecker, Tiffany (June 29, 2017). "Monsanto's Foes Are Branching Out". Environment, Health & Safety.

- ^ "Mass. Families file class action days after gas explosions". Archived from the original on October 14, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Patricia Winters Lauro (June 3, 1999). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is pushing supermarkets to sell a new brand of bottled water, with a twist". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Nestle Waters Announces Partnership with Waterkeeper Alliance". May 22, 2014. Nestle Waters.

- ^ Wesoff, Eric (May 31, 2012) "Ostara Nutrient Recovery Wins $14.5M From VantagePoint et al. Archived January 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". Greentech Media.

- ^ Wesoff, Eric (October 7, 2015) "Flow Battery Funding: Vionx Teams With Siemens, UTC, 3M, Starwood and Jabil". Greentech Media.

- ^ "Vionx, National Grid, and US Department of Energy Complete Installation of one of the World's Most Advanced Flow Batteries at Holy Name High School, Worcester, MA". www.businesswire.com. October 5, 2017. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Hilburn, Rachel Lewis (June 3, 2016). "CoastLine: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. on the Origin of CAFOs, Environmental Justice". WHQR.

- ^ "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Joins UISOL Board of Directors". August 25, 2010. McDonnell Group.

- ^ "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. joins Board of Directors". November 1, 2016. GridBright.com.

- ^ Spear, Stefanie (November 2, 2011). "EcoWatch and Waterkeeper Launch News Website". EcoWatch.

- ^ Melvin, Tessa (April 7, 1991) "Expanded Recycling Site Upsets an Ossining Neighborhood". New York Times. Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Reed, Susan (July 2, 1990). "Polluters, Beware! Riverkeeper John Cronin Patrols the Hudson and Pursues Those Who Foul Its Waters". People. Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hilburn, Rachel Lewis (June 3, 2016). "CoastLine: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. on the Origin of CAFOs, Environmental Justice". WHQR.org. Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wang, Ucilia (October 10, 2016) "Robert F Kennedy Jr takes big business to task over pollution at SXSW Eco". The Guardian. Archived October 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nirenberg, Michael Lee (May 23, 2017). "Conversation with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Archived March 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine" HuffPost

- ^ Brancaccio, David (January 21, 2005). "Science and Health: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.". PBS NOW. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bowermaster, Jon. (November 1992). "Last Run Down the Bio Bio". Town and Country Travel. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Clayton, Mark (April 20, 1994). "Cree Chief Wins Environmental Prize For Anti-Dam Effort". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kane, Joe (September 27, 1993). "With Spears from All Sides". The New Yorker. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1991). Foreword for Amazon Crude by Judith Kimerling. Published by Natural Resource Defense Council. February 19, 1991. p.131. ISBN 0960935851.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1995). Foreword for Clayoquot Mass Trials: Defending the Rainforest by Ronald MacIsaac and Anne Champagne (editors), published by New Society Publisher, February 1995, p.208. ISBN 0865713200.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (February 19, 1996). "Kennedy-Castro Encounter Touched by History". The New York Times. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rohter, Larry (February 25, 1996). "February 18–24; Meeting Across an Old Breach". The New York Times. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Matt (November 28, 2001). "The Unlikely Environmentalists". SFWeekly. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (December 3, 1998). "Rubbing Salt in the World Heritage Plan". Japan Times

- ^ Roberts, Bradley, MP, PLP (November 20, 2005). "Bradley Roberts on Clifton". Address to Bahamas House of Assembly. Archived October 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (November 29, 2016). "'I'll See You at Standing Rock'". EcoWatch. Archived October 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schaffer, Grayson (August 30, 2016). "Chile's Best Whitewater Rivers Won't Be Damned – For Now". Outside. Archived October 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (September 12, 2016). "20 Year David and Goliath Fist Fight Saves Patagonia's Futaleufú". EcoWatch. Archived October 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zukowski, Dan (June 22, 2017). "'An Act of War': RFK Jr. Puts U.S. Military and CAFOs on Blast for Trashing America's Waterways". EnviroNews. Archived October 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (May 16, 2003). "Defending our Environment and Health from the U.S. Military". Chicago Tribune. Archived October 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Le, Phuong (June 14, 2017). "Squamish Tribe, environmental groups sue Navy over hull cleaning". Kitsap Sun. Archived April 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (January 10, 2001). "Why Are We in Vieques?". Outside. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Greenhouse, Steven (July 16, 2001). "He's in Charge, in Demand, in Prison". The New York Times. Archived October 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "US Navy resumes Vieques war games". August 2, 2001. BBC News Archived June 29, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hernandez, Raymond (June 15, 2001). "Both Sides Attack Bush Plan To Halt Bombing on Vieques". The New York Times. Archived October 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr., (May 16, 2003). "Defending our environment and health from the U.S. military". Chicago Tribune. Archived October 21, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hahn Niman, Nicolette (February 17, 2009). Righteous Porkchop: Finding a Life and Good Food beyond Factory Farms. Published by William Morrow. p.336 ISBN 0061466492.

- ^ Robert F. Kennedy Jr.; Eric Schaeffer (September 20, 2003). "An Ill Wind From Factory Farms". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Rogers, Shelagh, host, and Carty, Bob, reporter (February 12, 2001). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. warns Canada about Pollution from Pork Industry". This Morning: CBC Digital Archives.

- ^ Ruf, Cory (May 25, 2013). "Robert Kennedy Jr. on his crusade for a 'green' economy". CBC News.

- ^ Overheard with Evan Smith. (May 5, 2011). "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. – Fossil Fuels". PBS

- ^ AP (April 26, 1984). "Exxon is Sued by New York over Use of Hudson Water". The New York Times.

- ^ Cronin, John; Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (1997). The Riverkeepers: Two Activists Fight to Reclaim Our Environment as a Basic Human Right. New York: Scribner. p.304. ISBN 0684839083.

- ^ AP (March 2, 2013). "New York fracking held as Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. talk health, AP sources say". Syracuse.com.

- ^ Isensee, Laura (October 28, 2009). "Robert Kennedy Jr: solar and natural gas belong together". Reuters

- ^ Marie Cusick (October 3, 2013). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. calls natural gas a 'catastrophe'". StateImpact Pennsylvania

- ^ Hakim, Danny (September 30, 2012). "Shift by Cuomo on Gas Drilling Prompts Both Anger and Praise". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Rally Against Pipelines". Salem Weekly. May 19, 2015.

- ^ Weber, Bob (June 12, 2013). "Prominent U.S. Keystone critic Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to visit oilsands". Macleans. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Spear, Stefanie (February 13, 2013). "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., Bill McKibben, Michael Brune, Among Others Will Risk Arrest Today at White House to Stop Tar Sands, Keystone XL Pipeline". EcoWatch.

- ^ Manning, Sarah Sunshine (November 16, 2016). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Visits Standing Rock on #NoDAPL Day of Action". Indian Country Today.

- ^ Zukowski, Dan (June 26, 2017). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Talks Tesla, Electric Big Rigs and the Impending Death of Fossil Fuels". EnviroNews.

- ^ Baxter, Brandon (June 3, 2014). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Praises Obama's Carbon Rules, Blasts Koch Brothers on 'The Ed Show'". EcoWatch.

- ^ Perks, Rob (March 11, 2010). "Mountaintop Removal Redux: Bobby vs. Blankenship II Archived January 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine". NRDC.

- ^ "Bobby Kennedy, Jr. Speaks on Coal Ash at Mt. Island Lake". July 25, 2013. Clean Air Carolina.

- ^ Yaggi, Marc, Waterkeeper Alliance (Winter 2013). "Around the World a Coalition Against Coal: Waterkeepers from Idaho to India Unite to Stop the Deadly International Coal Trade". Waterkeeper Magazine

- ^ Staff writer (2015). "At Pennsylvania Coal Mine, Feds Come to Rescue after State Fails". Waterkeeper Magazine Vol. 11. Issue 1.

- ^ The Last Mountain Archived October 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine (2011) IMDb.

- ^ Zukowski, Dan (June 23, 2017). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: 'I love James Hansen, but he is wrong on [the nuclear power issue]'". EniroNews.

- ^ Brooks, Jon (June 22, 2011). "Interview: Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on 'Uninsurable' Nuke Energy Industry, BrightSource Solar Project". KQED.

- ^ Paul Chin photograph. (June 15, 1981). Caption reads, "Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. speaks out against nuclear power". Archivegrid, Los Angeles Public Library.

- ^ "Nuclear Ticking Time Bomb 28 Miles From NYC – America's Lawyer". Indian Point Safe Energy Coalition. April 4, 2017.

- ^ Indian Point: Imagining the Unimaginable Archived February 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, (TV movie 2004). IMDb.

- ^ Trueheart, Charles (April 7, 1994). "Quebec Power Company Finds Its High-Voltage Plans Short-Circuited". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Bowermaster, Jon (November 1992). "Last Run Down the Bio Bio". Town and Country.

- ^ a b Guynup, Sharon (June 7, 2002). "Belize Dam Fight Heats Up as Court Prepares to Rule". National Geographic Today.

- ^ Leaney, Stephen (April 11, 2003). "British finding 'secret war' in green laws by Kennedy". International Press Service.

- ^ Ari Hershowitz, "A Solid Foundation: Belize's Chalillo Dam and Environmental Decisionmaking[permanent dead link]", Ecology Law Quarterly, Vol. 35, pp. 73–106.

- ^ "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on the river along with numerous leaders of conservation organizations". August 2, 2004. Canadian Parks And Wilderness Society – Quebec Chapter.

- ^ Goujard, Clothilde (September 14, 2017). "Hydro-Quebec abandons dam project on majestic Magpie River". National Observer.

- ^ Martinez, Rodrigo (November 19, 2017). "Robert Kennedy Jr por Hidroaysén: 'Los beneficios económicos eran para unos pocos millonarios'". La Tercera. Archived November 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Radio Equalizer: Brian Maloney: RFK Jr Tirade, Air America, John Stossel, Rush Limbaugh, Sean Hannity". Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (July 18, 2011). "Nantucket's Wind Power Rip-off". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ Griscom, Amanda (October/November 2004). "Environmental Justice". Mother Earth News.

- ^ Roberts, Joel (January 29, 2003). "Bush: $1.2 Billion For Hydrogen Cars". CBS News. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (February 16, 2003). "A Bad Element". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. on the Climate Crisis: What Must Be Done". Rolling Stone. June 28, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Jr., Robert F. (2004). Crimes Against Nature: How George W. Bush and His Corporate Pals Are Plundering the Country and Hijacking Our Democracy. HarperCollins. ISBN 0060746882.

- ^ "The 100 People Who Are Changing America". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Robert F. Kennedy Jr. advocates for green power". The Mercury News. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Dixon, Darius (October 12, 2012). "RFK Jr. to greens: Not Obama's fault". Politico.

- ^ Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. (2015) "What State Attorneys General can do about Climate-Change Deniers" Letter from the President", Waterkeeper Magazine Vol. 11. Issue 1.

- ^ Spear, Stefanie (September 10, 2015). "Koch Brothers: Apocalyptical Forces of Ignorance and Greed, Says RFK Jr." EcoWatch.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (September 22, 2014). "Robert F. Kennedy Jr.: "The Only Thing We Have in Our Power is People Power". Democracy Now.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (February 1974). "Poor Chile". Atlantic Monthly.

- ^ Kennedy Jr. Robert F. (February 25, 1979). "Plea to Pakistan". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (February 23, 1979). "Legacy at Stake in Pakistan". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (December 16, 1975) "Politics and Assassinations". The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (December 17, 2005). "America's anti-torture tradition". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Congressional Record Index. (Vol 151 – Part 23). January 4, 2005 - December 30, 2005. by Senator Edward M. Kennedy. P.2054

- ^ Robert F. Kenney Jr. (February 22, 2016). "Why the Arabs Don't Want Us in Syria". Politico. Archived from the original on January 7, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. Jr. (February 25, 2016). "Syria: Another Pipeline War". EcoWatch.

- ^ Brancaccio, David (January 21, 2005). "Science and Health: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.". PBS NOW.

- ^ New York League of Conservative Voters. June 18, 2014. NYLCV Letterhead.

- ^ Welch, Craig (October 29, 2003). "RFK Jr. blasts Bush, champions Kerry". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Jeff Zeleny; Carl Hulse (January 28, 2008). "Kennedy Chooses Obama, Spurning Plea by Clintons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ "eTown at the 2008 Democratic National Convention (Denver)". October 8, 2008. etown.org