Katyn massacre: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

→Further reading: cleanup book sources |

||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

== Further reading == |

== Further reading == |

||

{{refbegin| |

{{refbegin|2}} |

||

* |

* {{Cite book|editor1-last=Cienciala|editor1-first=Anna M.|editor2-last=S. Lebedeva|editor2-first=Natalia|editor3-last=Materski|editor3-first=Wojciech|title=Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment|series=Annals of Communism Series|publisher=[[Yale University Press]]|year=2008|isbn=0-300-10851-6}} |

||

* |

* {{Cite book|last1=Komorowski|first1=Eugenjusz A.|last2=Gilmore|first2=Joseph L.|year=1974|title=Night Never Ending|publisher=Avon Books}} |

||

* {{Cite book| |

* {{Cite book|last=Paul|first=Allen|authorlink=Allen Paul|year=2010|title=Katyń: Stalin's Massacre and the Triumph of Truth|publisher=Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, IL|isbn=978-0-87580-634-1}} |

||

* {{Cite book |

* {{Cite book|last=Paul|first=Allen|year=1996|title=Katyń: Stalin's massacre and the seeds of Polish Resurrection publisher = Annapolis, Md., Naval Institute Press|isbn=1-55750-670-1}} |

||

* {{Cite book| |

* {{Cite book|last=Paul|first=Allen| year = 1991 | title = Katyn: The Untold Story of Stalin's Polish Massacre|publisher=Scribner Book Company|isbn=0-684-19215-2}} |

||

* |

* {{Cite journal|last=Sandford|first=George|authorlink=George Sanford (scholar)|title=The Katyn Massacre and Polish–Soviet relations 1941–1943|journal=[[Journal of Contemporary History]]|volume=41|issue=1|pages=95–111|url=http://jch.sagepub.com/cgi/reprint/41/1/95.pdf|format=PDF}} |

||

* |

* {{Cite book|last=Swianiewicz|first=Stanisław|authorlink=Stanisław Swianiewicz|title=W cieniu Katynia|origyear=1976|trans_title=In the Shadow of Katyn: Stalin's Terror|publisher=Borealis Pub|year=2000|isbn=1-894255-16-X}} |

||

* |

* {{Cite book|last=Zaslavsky|first=Victor|url=http://www.telospress.com/main/index.php?main_page=product_info&products_id=366|title=Class Cleansing: The Katyn Massacre|others=Kizer Walker (trans.)|publisher=Telos Press Publishing|year=2008|isbn=978-0-914386-41-4}} |

||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

Revision as of 19:53, 16 June 2011

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre (Polish: zbrodnia katyńska, mord katyński, 'Katyń crime'; Russian: Катынский расстрел), was a mass execution[1] of Polish nationals carried out by the Soviet secret police NKVD in April–May 1940. It was based on Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all members of the Polish Officer Corps, dated 5 March 1940. This official document was approved and signed by the Soviet Politburo, including its leader, Joseph Stalin.[2] The number of victims is estimated at about 22,000, the most commonly cited number being 21,768.[3] The victims were murdered in the Katyn Forest in Russia, the Kalinin and Kharkov prisons and elsewhere.[4] About 8,000 were officers taken prisoner during the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, 6,000 police officers, with the rest being Polish intelligentsia arrested for allegedly being "intelligence agents, gendarmes, landowners, saboteurs, factory owners, lawyers, officials and priests."[3]

The term "Katyn massacre" originally referred specifically to the massacre at Katyn Forest, near the villages of Katyn and Gnezdovo (ca. 19 kilometres (12 mi) west of Smolensk, Russia), of Polish military officers in the Kozelsk prisoner-of-war camp. This was the largest of several simultaneous executions of prisoners of war. Other executions occurred at the geographically distant Starobelsk and Ostashkov camps,[5] at the NKVD headquarters in Smolensk, at a Smolensk slaughterhouse,[2] and at prisons in Kalinin (Tver), Kharkov, Moscow, and other Soviet cities.[3] Other executions took place at various locations in Belarus and Western Ukraine, based on special Katyn lists of Polish prisoners, prepared by the NKVD specifically for those regions.[3] The modern Polish investigation of the killings covered not only the massacre at Katyn forest, but also the other mass murders mentioned above. Polish organisations, such as the Katyn Committee and the Federation of Katyn Families, consider the victims murdered at the locations other than Katyn as part of the overall massacre.[3]

Nazi Germany announced the discovery of mass graves in the Katyn Forest in 1943.[6] The revelation led to the end of diplomatic relations between Moscow and the London-based Polish government-in-exile. The Soviet Union continued to deny responsibility for the massacres until 1990, when it officially acknowledged and condemned the perpetration of the killings by the NKVD.[3][7][8][a]

An investigation conducted by the Prosecutor General's Office of the Soviet Union (1990–1991) and the Russian Federation (1991–2004), has confirmed Soviet responsibility for the massacres. It was able to confirm the deaths of 1,803 Polish citizens but refused to classify this action as a war crime or an act of genocide. The investigation was closed on grounds that the perpetrators of the massacre were already dead, and since the Russian government would not classify the dead as victims of Stalinist repression, formal posthumous rehabilitation was ruled out.[9] The human rights society Memorial issued a statement which declared "this termination of investigation is inadmissible" and that their confirmation of only 1,803 people killed "requires explanation because it is common knowledge that more than 14,500 prisoners were killed."[10] In November 2010, the Russian State Duma approved a declaration blaming Stalin and other Soviet officials for having personally ordered the massacre.[11]

Background

On 1 September 1939, Nazi Germany, along with a small Slovak contingent, invaded Poland. Meanwhile, Britain and France, pledged by the Polish-British Common Defence Pact and Franco-Polish Military Alliance to attack Germany in the case of such an invasion, demanded that Germany withdraw. On 3 September 1939, after it failed to do so, France, Britain, and most countries of the British Commonwealth declared war on Germany but provided little military support to Poland other than a French attack into the Saarland.[12] They took little other significant military action during what became known as the Phoney War.[13]

The Soviet Union began its own invasion on 17 September, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The Red Army advanced quickly and met little resistance,[14] as Polish forces facing them were under orders not to engage the Soviets. About 250,000[3][15]-454,700[16] Polish soldiers and policemen had become prisoners and were interned by the Soviet authorities. Some were freed or escaped quickly, while 125,000 were imprisoned in prison camps run by NKVD.[3] Out of those, 42,400 soldiers, mostly soldiers of Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnicity serving in the Polish army who lived in the former Polish territories now annexed by the Soviet Union, were released in October.[15][15][17][18] The 43,000 soldiers born in West Poland, then under German control, were transferred to the Germans; in turn the Soviets received 13,575 Polish prisoners from the Germans.[15][18]

In addition to military and government personnel, other Polish citizens suffered from repressions. Thousands of Polish intelligentsia were also imprisoned, arrested for allegedly being "intelligence agents, gendarmes, landowners, saboteurs, factory owners, lawyers, officials and priests."[3] Since Poland's conscription system required every unexempted university graduate to become a reserve officer,[19] the NKVD was able to round up much of the Polish intelligentsia.[f] According to estimates by IPN, roughly 320,000 Polish citizens were deported to the Soviet Union (this figure is questioned by some other historians, standing by the older estimate of about 700,000-1,000,000).[20][21][22] IPN estimates the number of Polish citizens that perished under the Soviet rule during World War II at 150,000 (correcting older estimates of up to 500,000).[20][21][22] Of the one group of 12,000 Poles sent to Dalstroy camp (near Kolyma) in 1940-1941, most POWs, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[23] According to Tadeusz Piotrowski, "...during the war and after 1944, 570,387 Polish citizens had been subjected to some form of Soviet repression."[24]

As early as September 19, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs and First Rank Commissar of State Security, Lavrentiy Beria, ordered the NKVD to create the Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees to manage Polish prisoners. The NKVD took custody of Polish prisoners from the Red Army, and proceeded to organise a network of reception centers and transit camps and arrange rail transport to prisoner-of-war camps in the western USSR. The largest camps were located at Kozelsk (Optina Monastery), Ostashkov (Stolbnyi Island on Seliger Lake near Ostashkov) and Starobelsk. Other camps were at Jukhnovo (rail station "Babynino"), Yuzhe (Talitsy), rail station "Tyotkino" (90 kilometres (56 mi) from Putyvl), Kozelshchyna, Oranki, Vologda (rail station "Zaonikeevo") and Gryazovets.[25]

Kozelsk and Starobelsk were used mainly for military officers, while Ostashkov was used mainly for Polish boy scouts, gendarmes, police and prison officers.[26] Some prisoners members were members of other groups of Polish intelligentsia, such a s priests, landowners and law personnel.[26] The approximate distribution of men throughout the camps was as follows: Kozelsk, 5,000; Ostashkov, 6,570; and Starobelsk, 4,000. They totalled 15,570 men.[27]

According to a report from 19 November 1939, the NKVD had about 40,000 Polish POWs: about 8,000-8,500 officers and warrant officers, 6,000-6,500 police officers and 25,000 soldiers and NCOs who were still being held as POWs.[3][18][28][29] In December, a wave of arrests took into custody some Polish officers who were not yet imprisoned, Ivan Serov reported to Beria on 3 December that "in all, 1,057 former officers of the Polish Army had been arrested."[15] The 25,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers were assigned to forced labors (road construction, heavy metallurgy).[15]

Once at the camps, from October 1939 to February 1940, the Poles were subjected to lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation by NKVD officers such as Vasily Zarubin. The prisoners assumed that they would be released soon, but the interviews were in effect a selection process to determine who would live and who would die.[2][30] According to NKVD reports, if the prisoners could not be induced to adopt a pro-Soviet attitude, they were declared "hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority."[2]

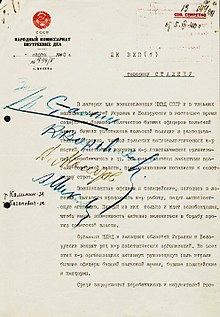

On 5 March 1940, pursuant to a note to Stalin from Beria, four members of the Soviet Politburo - Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Kliment Voroshilov and Anastas Mikoyan - signed an order to execute 25,700 Polish "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries" kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine and Belarus.[31][c] The reason for the massacre, according to historian Gerhard Weinberg, is that Stalin wanted to deprive a potential future Polish military of a large portion of its military talent: "It has been suggested that the motive for this terrible step [the Katyn massacre] was to reassure the Germans as to the reality of Soviet anti-Polish policy. This explanation is completely unconvincing in view of the care with which the Soviet regime kept the massacre secret from the very German government it was supposed to impress... A more likely explanation is that... [the massacre] should be seen as looking forward to a future in which there might again be a Poland on the Soviet Union's western border. Since he intended to keep the eastern portion of the country in any case, Stalin could be certain that any revived Poland would be unfriendly. Under those circumstances, depriving it of a large proportion of its military and technical elite would make it weaker."[32] In addition, Soviets realized that the prisoners constituted a large body of trained and motivated Poles who would not accept the Fourth Partition of Poland.[3]

Executions

The number of victims is estimated at about 22,000, the most commonly cited number being 21,768.[3] According to Soviet documents declassified in 1990, 21,857 Polish internees and prisoners were executed after 3 April 1940: 14,552 prisoners of war (most or all of them from the three camps) and 7,305 prisoners in western parts of the Belarusian and Ukrainian SSRs.[5][b] Of them 4,421 were from Kozelsk, 3,820 from Starobelsk, 6,311 from Ostashkov, and 7,305 from Belarusian and Ukrainian prisons.[5][b] Head of the NKVD POW department, Maj. General P.K. Soprunenko, organized "selections" of Polish officers to be massacred at Katyn and elsewhere.[33]

Those who died at Katyn included an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 3,420 NCOs, seven chaplains, three landowners, a prince, 43 officials, 85 privates, and 131 refugees. Also among the dead were 20 university professors. Many sources claim that prominent mathematician Stefan Kaczmarz was among the victims, but the Polish version of Wikipedia states that he died in 1939, most likely in combat operations near Warsaw. There were also 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists as well as about 200 pilots. In all, the NKVD executed almost half the Polish officer corps.[2] Altogether, during the massacre the NKVD murdered 14 Polish generals:[34] Leon Billewicz (ret.), Bronisław Bohatyrewicz (ret.), Xawery Czernicki (admiral), Stanisław Haller (ret.), Aleksander Kowalewski (ret.), Henryk Minkiewicz (ret.), Kazimierz Orlik-Łukoski, Konstanty Plisowski (ret.), Rudolf Prich (murdered in Lviv), Franciszek Sikorski (ret.), Leonard Skierski (ret.), Piotr Skuratowicz, Mieczysław Smorawiński and Alojzy Wir-Konas (promoted posthumously). A mere 395 prisoners were saved from the slaughter,[3] among them Stanisław Swianiewicz and Józef Czapski.[2] They were taken to the Yukhnov camp and then to Gryazovets.[25]

Up to 99% of the remaining prisoners were subsequently murdered. People from the Kozelsk camp were murdered in the usual mass murder site of Smolensk countryside, in the Katyn forest; people from the Starobelsk camp were murdered in the inner NKVD prison of Kharkov and the bodies were buried near Piatykhatky; and police officers from the Ostashkov camp were murdered in the inner NKVD prison of Kalinin (Tver) and buried in Mednoye.[25]

Detailed information on the executions in the Kalinin NKVD prison was given during the hearing by Dmitrii Tokarev, former head of the Board of the District NKVD in Kalinin. According to Tokarev, the shooting started in the evening and ended at dawn. The first transport on 4 April 1940, carried 390 people, and the executioners had a hard time killing so many people during one night. The following transports were no greater than 250 people. The executions were usually performed with German-made 7.65 mm Walther PPK pistols supplied by Moscow, but 7.62x38R Nagant M1895 revolvers were also used.[35] The executioners used German weapons rather than the standard Soviet revolvers, as the latter were said to offer too much recoil, which made shooting painful after the first dozens of executions.[36] Vasili Mikhailovich Blokhin, chief executioner for the NKVD—and quite possibly the most prolific executioner in history—is reported to have personally shot and killed 7,000 of the condemned, some as young as 18, from the Ostashkov camp at Kalinin prison over a period of 28 days in April 1940.[33][37]

The killings were methodical. After the personal information of the condemned was checked, he was handcuffed and led to a cell insulated with stacks of sandbags along the walls and a felt-lined, heavy door. The victim was told to kneel in the middle of the cell, was then approached from behind by the executioner and immediately shot in the back of the head. The body was carried out through the opposite door and laid in one of the five or six waiting trucks, whereupon the next condemned was taken inside. In addition to muffling by the rough insulation in the execution cell, the pistol gunshots were also masked by the operation of loud machines (perhaps fans) throughout the night. This procedure went on every night, except for the May Day holiday.[38]

Some 3,000 to 4,000 Polish inmates of Ukrainian prisons and those from Belarus prisons were probably buried in Bykivnia and in Kurapaty respectively.[39] Porucznik Janina Lewandowska, daughter of Gen. Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki, was the only woman executed during the massacre at Katyn.[38][40]

Discovery

The fate of the Polish prisoners was raised soon after the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, when the Polish government-in-exile and the Soviet government signed the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement to fight Nazi Germany and form a Polish army on Soviet territory. When the Polish general Władysław Anders began organizing this army, he requested information about Polish officers. During a personal meeting, Stalin assured him and Władysław Sikorski, the Polish Prime Minister, that all the Poles were freed, and that not all could be accounted because the Soviets "lost track" of them in Manchuria.[41][42][43]

In 1942, Polish railroad workers heard from the locals about a mass grave of Polish soldiers at Kozielsk near Katyn, found one of the graves and reported it to the Polish Secret State.[44] The discovery was not seen as important, as nobody thought that the discovered grave could contain so many victims.[44] In early 1943 German officer, Rudolf Christoph Freiherr von Gersdorff, serving as the intelligence liaison between Wehrmacht's Army Group Center and Abwehr, received reports about mass graves of Polish military officers in the forest on Goat Hill near Katyn, and passed them up to his superiors (sources vary on when exactly did Germans became aware of the graves — from "late 1942" to January/February 1943, and when did the German top decision makers in Berlin received those reports (as early as 1 March or as late as 4 April).[45] Joseph Goebbels saw this discovery as an excellent tool to drive a wedge between Poland, Western Allies, and the Soviet Union, and reinforce the Nazi propaganda line about the horrors of Bolshevism and American and British subservience to it.[46] On 13 April, Berlin Radio broadcast to the world that German military forces in the Katyn forest near Smolensk had uncovered "a ditch ... 28 metres long and 16 metres wide [92 ft by 52 ft], in which the bodies of 3,000 Polish officers were piled up in 12 layers."[47] The broadcast went on to charge the Soviets with carrying out the massacre in 1940.

The Germans assembled and brought in a European commission consisting of twelve forensic experts and their staffs from Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Croatia, the Netherlands, Romania, Sweden, Slovakia, and Hungary.[48] After the war, two of the twelve, the Bulgarian, Marko Markov and the Czech, Frantisek Hajek, their countries occupied by the Soviet Union, were forced to recant their evidence, defending the Soviets and blaming the Germans.[49] The Katyn massacre was beneficial to Nazi Germany, which used it to discredit the Soviet Union. Goebbels wrote in his diary on 14 April 1943: "We are now using the discovery of 12,000 Polish officers, murdered by the GPU, for anti-Bolshevik propaganda on a grand style. We sent neutral journalists and Polish intellectuals to the spot where they were found. Their reports now reaching us from ahead are gruesome. The Führer has also given permission for us to hand out a drastic news item to the German press. I gave instructions to make the widest possible use of the propaganda material. We shall be able to live on it for a couple weeks."[50] The Germans won a major propaganda victory, portraying communism as a danger to Western civilization; moreover, General Sikorski's unease threatened to unravel the alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union.

The Soviet government immediately denied the German charges and claimed that the Polish prisoners of war had been engaged in construction work west of Smolensk and consequently were captured and executed by invading German units in August 1941. The Soviet response on 15 April to the German initial broadcast of 13 April, prepared by the Soviet Information Bureau, stated that "[...]Polish prisoners-of-war who in 1941 were engaged in construction work west of Smolensk and who [...] fell into the hands of the German-Fascist hangmen [...]."[51]

The Allies were aware that the Nazis had found a mass grave as the discovery transpired, through radio transmissions intercepted and decrypted by Bletchley Park. German experts and the international commission, which was invited by Germany, investigated the Katyn corpses and soon produced physical evidence that the massacre took place in early 1940, at a time when the area was still under Soviet control.[52]

In April 1943, when the Polish government-in-exile insisted on bringing the matter to the negotiation table with the Soviets and on an investigation by the International Red Cross,[52][53] Stalin accused the Polish government of collaborating with Nazi Germany, broke diplomatic relations with it,[54][55] and started a campaign to get the Western Allies to recognize the alternative Polish pro-Soviet government in Moscow led by Wanda Wasilewska.[56] Sikorski, whose uncompromising stance on that issue was beginning to create a rift between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, died in an air crash in July—an event that was convenient to the Allied leaders.[57]

Soviet actions

Having retaken the Katyn area almost immediately after the Red Army had recaptured Smolensk, around September–October 1943, NKVD forces began a cover-up.[2][58] A cemetery the Germans had permitted the Polish Red Cross to build was destroyed and other evidence removed.[2] Witnesses were "interviewed", and threatened with being arrested as German collaborators if their testimonies disagreed with the official line.[58] A preeliminary report was issued by NKVD operatives Vsevolod Merkulov and Sergei Kruglov, dated 10–11 January 1944, concluding that the Polish officers were shot by the Germans.[58]

In January 1944, the Soviet Union sent a more prestigious Special Commission for Determination and Investigation of the Shooting of Polish Prisoners of War by German-Fascist Invaders in Katyn Forest (Russian: Специальная Комиссия по установлению и расследованию обстоятельств расстрела немецко-фашистскими захватчиками в Катынском лесу военнопленных польских офицеров, Spetsial'naya Kommissiya po ustanovleniyu i rassledovaniyu obstoyatel'stv rasstrela nemetsko-fashistskimi zakhvatchikami v Katynskom lesu voyennoplennyh polskih ofitserov) to the site.[2][58] It was headed by Nikolai Burdenko, the President of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the USSR (hence the commission is often known as the "Burdenko Commission"), who volunteered, and received an official permission, investigate the incident.[2][58] Its members included internationally known figures such as the writer Alexei Tolstoy, but no foreign personnel were allowed to join the Commission.[2][58] The Burdenko Commission exhumed the bodies, rejected the 1943 German findings that the Poles were shot by the Soviets, and laid the guilt with the Germans and concluded that all the shootings were done by German occupation forces in autumn 1941.[2] Despite no evidence, it also blamed the Germans for shooting Russian prisoners of war, used as labor to dug the pits.[2] It is uncertain how many members of the commission were duped by the falsified reports and evidence, and how many suspected the truth; Cienciala and Materski note that the Commission had no choice but to issue findings in line with Merkulov-Kruglov report, and that Burdenko himself likely was aware of the cover up, and reportedly admitted some of that to friends and family, shortly before his death.[58][58] It would be consistently cited by Soviet sources till the official admission of guilt by the Soviet government on 13 April 1990.[58]

Western response

The growing Polish-Soviet crisis was beginning to threaten Western-Soviet relations at a time when the Poles' importance to the Allies, significant in the first years of the war, was beginning to fade, due to the entry into the conflict of the military and industrial giants, the Soviet Union and the United States. In retrospective review of records, both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt were increasingly torn between their commitments to their Polish ally, the uncompromising stance of Sikorski and the demands by Stalin and his diplomats.[59]

In private, Churchill agreed that the atrocity was likely carried out by the Soviets. According to Count Edward Raczyński, Churchill admitted on 15 April 1943 during a conversation with General Sikorski: "Alas, the German revelations are probably true. The Bolsheviks can be very cruel."[60] However, at the same time, on 24 April 1943 Churchill assured the Soviets: "We shall certainly oppose vigorously any 'investigation' by the International Red Cross or any other body in any territory under German authority. Such investigation would be a fraud and its conclusions reached by terrorism."[61] Unofficial or classified UK documents concluded that Soviet guilt was a "near certainty", but the alliance with the Soviets was deemed to be more important than moral issues; thus the official version supported the Soviet version, up to censoring the contradictory accounts.[52] Churchill's own post-war account of the Katyn affair gives little further insight. In his memoirs, he refers to the 1944 Soviet inquiry into the massacre, which found the Germans guilty and adds, "belief seems an act of faith."[62]

At the beginning of 1944, Ron Jeffery an agent of British and Polish intelligence in occupied Poland eluded the Abwehr and travelled to London with a report from Poland to the British government. His efforts were at first highly regarded but subsequently ignored by the British, which a disillusioned Jeffery attributed to the treachery of Kim Philby and other high-ranking communist agents entrenched in the British system. Jeffery tried to inform the British government about the Katyn massacre but finally was released from the Army.[63][64]

In the United States, a similar line was taken, notwithstanding that two official intelligence reports into the Katyn massacre were produced that contradicted the official position. In 1944 Roosevelt assigned his special emissary to the Balkans, Navy Lieutenant Commander George Earle, to produce a report on Katyn. Earle concluded that the massacre was committed by the Soviet Union. Having consulted with Elmer Davis, the director of the Office of War Information, Roosevelt rejected the conclusion (officially), declared that he was convinced of Nazi Germany's responsibility, and ordered that Earle's report be suppressed. When Earle formally requested permission to publish his findings, the President issued a written order to desist. Earle was reassigned and spent the rest of the war in American Samoa.[2]

A further report in 1945, supporting the same conclusion, was produced and stifled. In 1943, two US POWs – Lt. Col. Donald B. Stewart and Col. John H. Van Vliet – had been taken by Germans to Katyn for an international news conference.[65] Later, in 1945, Van Vliet submitted a report concluding that the Soviets were responsible for the massacre. His superior, Maj. Gen. Clayton Bissell, Gen. George Marshall's assistant chief of staff for intelligence, destroyed the report.[66] During the 1951–1952 Congressional investigation into Katyn, Bissell defended his action before Congress, arguing that it was not in the US interest to antagonize an ally whose assistance was still needed against the Empire of Japan.[2]

Inconclusive Nuremberg trials

From 28 December 1945 to 4 January 1946, seven servicemen of the German Wehrmacht were tried by a Soviet military court in Leningrad. One of them, Arno Diere, was charged with helping to dig the Katyn graves during the execution. Diere, who was accused of murder using machine-guns in Soviet villages, confessed to having taken part in burial (though not the execution) of 15–20 thousand Polish POWs in Katyn. For this he was spared execution and was given 15 years of hard labor. His confession was full of absurdities, and thus he was not used as a Soviet prosecution witness during the Nuremberg trials. In a note of 29 November 1954 he recanted his confession, claiming that he was forced to confess by the investigators.[67]

At the London conference that drew up the indictments of German war crimes before the Nuremberg trials, the Soviet negotiators put forward the allegation, "In September 1941, 925 Polish officers who were prisoners of war were killed in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk." The US negotiators agreed to include it, but were "embarrassed" by the inclusion (noting that the allegation had been debated extensively in the press) and concluded that it would be up to the Soviets to sustain it.[68] At the trials in 1946, Soviet General Roman Rudenko, raised the indictment, stating that "one of the most important criminal acts for which the major war criminals are responsible was the mass execution of Polish prisoners of war shot in the Katyn forest near Smolensk by the German fascist invaders,"[69] but failed to make the case and the US and British judges dismissed the charges.[70] Also, it was not the purpose of the court to determine whether Germany or the Soviet Union was responsible for the crime, but rather to attribute the crime to at least one of the defendants, which the court was unable to do.[71]

Cold War views

In 1951 and 1952, in the background of the Korean War, a U.S. Congressional investigation chaired by Rep. Ray J. Madden and known as the Madden Committee investigated the Katyn massacre. It concluded that the Poles had been killed by the Soviets[2] and recommended that the Soviets be tried before the International Court of Justice.[65] Still, the question of responsibility remained controversial in the West as well as behind the Iron Curtain. In the United Kingdom in the late 1970s, plans for a memorial to the victims bearing the date 1940 (rather than 1941) were condemned as provocative in the political climate of the Cold War. It has been sometimes speculated that the choice made in 1969 for the location of the BSSR's war memorial at the former Belarusian village named Khatyn, a site of a 1943 Nazi massacre in which the entire village with its whole population was burned, have been made to cause confusion with Katyn.[72][73] The two names are similar or identical in many languages, and were often confused.[2][74]

In Poland, the pro-Soviet authorities covered up the matter in concord with Soviet propaganda, deliberately censoring any sources that might provide information about the crime. Katyn was a forbidden topic in postwar Poland. Not only did government censorship suppress all references to it, but even mentioning the atrocity was dangerous. Yet if Katyn became erased from Poland's official history, erasing it from people's memory was impossible. In 1981, Polish trade union Solidarity erected a memorial with the simple inscription "Katyn, 1940" but it was confiscated by the police, to be replaced with an official monument "To the Polish soldiers—victims of Hitlerite fascism—reposing in the soil of Katyn". Nevertheless, every year on Zaduszki, similar memorial crosses were erected at Powązki cemetery and numerous other places in Poland, only to be dismantled by the police overnight. Katyn remained a political taboo in communist Poland until the fall of the Eastern bloc in 1989.[2]

Meantime, in the Soviet Union during the 1950s, head of KGB Aleksandr Shelepin proposed and carried out a destruction of many documents related to the Katyn massacre, to minimize the chances that the truth would be revealed.[75][76] Ironically, his 3 March 1959 note to Nikita Khrushchev, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles and with the proposal to destroy their personal files, became one of the documents that were preserved and eventually made public.[75][76][77][78][b]

Revelations

From the late 1980s, pressure was put not only on the Polish government, but on the Soviet one as well.[by whom?] Polish academics tried to include Katyn in the agenda of the 1987 joint Polish-Soviet commission to investigate censored episodes of the Polish-Russian history.[2] In 1989 Soviet scholars revealed that Joseph Stalin had indeed ordered the massacre, and in 1990 Mikhail Gorbachev admitted that the NKVD had executed the Poles and confirmed two other burial sites similar to the site at Katyn: Mednoye and Piatykhatky.

On 30 October 1989, Gorbachev allowed a delegation of several hundred Poles, organized by a Polish association named Families of Katyń Victims, to visit the Katyn memorial. This group included former U.S. national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski. A Mass was held and banners hailing the Solidarity movement were laid. One mourner affixed a sign reading "NKVD" on the memorial, covering the word "Nazis" in the inscription such that it read "In memory of Polish officers murdered by the NKVD in 1941." Several visitors scaled the fence of a nearby KGB compound and left burning candles on the grounds.[79] Brzezinski commented that:

It isn't a personal pain which has brought me here, as is the case in the majority of these people, but rather recognition of the symbolic nature of Katyń. Russians and Poles, tortured to death, lie here together. It seems very important to me that the truth should be spoken about what took place, for only with the truth can the new Soviet leadership distance itself from the crimes of Stalin and the NKVD. Only the truth can serve as the basis of true friendship between the Soviet and the Polish peoples. The truth will make a path for itself. I am convinced of this by the very fact that I was able to travel here.[80]

Brzezinski further stated that:

The fact that the Soviet government has enabled me to be here—and the Soviets know my views—is symbolic of the breach with Stalinism that perestroika represents.[81]

His remarks were given extensive coverage on Soviet television. At the ceremony he placed a bouquet of red roses bearing a handwritten message penned in both Polish and English: "For the victims of Stalin and the NKVD. Zbigniew Brzezinski."[82]

On 13 April 1990, the forty-seventh anniversary of the discovery of the mass graves, the USSR formally expressed "profound regret" and admitted Soviet secret police responsibility.[83][a] The day was declared a worldwide Katyn Memorial Day (Polish: Światowy Dzień Pamięci Ofiar Katynia).[84]

Recent developments

Russia and Poland remained divided on the legal description of the Katyn crime, with the Poles considering it a case of genocide and demanding further investigations, as well as complete disclosure of Soviet documents.[85][86]

After Poles and Americans discovered further evidence in 1991 and 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin released the top-secret documents from the sealed "Package №1." and transferred them to the new Polish president Lech Wałęsa,[2][87][88] Among the documents was a proposal by Lavrenty Beria dated with 5 March 1940 to execute 25,700 Poles from Kozelsk, Ostashkov and Starobels camps, and from certain prisons of Western Ukraine and Belarus, signed by Stalin (among others).[d][2][88] Among documents transferred to the Poles was the Aleksandr Shelepin's 3 March 1959 note to Nikita Khrushchev, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles and with the proposal to destroy their personal files to reduce the chance of anybody ever discovering documents related to the massacre.[78][b] The revelations were also publicized in the Russian press, where they were seen as part of the power struggle between Yeltsin and Gorbachev.[88]

In 1991, the Chief Military Prosecutor for the Soviet Union began proceedings against P.K. Soprunenko for his role in the Katyn murders, but declined as Soprunenko was 83, almost blind and recovering from a cancer operation. During interrogation, he used the Kaltenbrunner defense—denying his own signature, etc.[33] In June 1998, Yeltsin and Aleksander Kwaśniewski agreed to construct memorial complexes at Katyn and Mednoye, the two NKVD execution sites on Russian soil. However, in September of that year the Russians also raised the issue of Soviet prisoner of war deaths in the camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–1924). About 16,000 to 20,000 POWs died in those camps due to communicable diseases.[89][90] Some Russian officials argued that it was 'a genocide comparable to Katyń'.[2] A similar claim was raised in 1994; such attempts are seen by some, particularly in Poland, as a highly provocative Russian attempt to create an 'anti-Katyn' and 'balance the historical equation'.[91]

During Kwaśniewski's visit to Russia in September 2004, Russian officials announced that they are willing to transfer all the information on the Katyn massacre to the Polish authorities as soon as it is declassified.[92] In March 2005 the Prosecutor's General Office of the Russian Federation concluded the decade-long investigation of the massacre. Chief Military Prosecutor Alexander Savenkov announced that the investigation was able to confirm the deaths of 1,803 out of 14,542 Polish citizens from three Soviet camps who had been sentenced to death.[93] He did not address the fate of about 7,000 victims who had been not in POW camps, but in prisons. Savenkov declared that the massacre was not a genocide, that Soviet officials who had been found guilty of the crime were dead and that, consequently, "there is absolutely no basis to talk about this in judicial terms". 116 out of 183 volumes of files gathered during the Russian investigation, were declared to contain state secrets and were classified.[10][94]

On 22 March 2005 the Polish Sejm unanimously passed an act, requesting the Russian archives to be declassified.[95] The Sejm also requested Russia to classify the Katyn massacre as a crime of genocide.[85] The resolution stressed that the authorities of Russia "seek to diminish the burden of this crime by refusing to acknowledge it was genocide and refuse to give access to the records of the investigation into the issue, making it difficult to determine the whole truth about the murder and its perpetrators."[85] In 2008, Polish Foreign Ministry asked the government of Russia about alleged footage of the massacre filmed by the NKVD during the killings. Polish officials believe that this footage, as well as further documents showing cooperation of Soviets with the Gestapo during the operations, are the reason for Russia's decision to classify most of documents about the massacre.[96] In June 2008, Russian courts consented to hear a case about the declassification of documents about Katyn and the judicial rehabilitation of the victims. In an interview with a Polish newspaper, Vladimir Putin called Katyn a "political crime."[97]

The European Court of Human Rights communicated the Katyn claims to the Russian government on 10 October 2008.[98] A number of pro-Soviet Russian politicians and commentators and Communist party members continue to deny all Soviet guilt, call the released documents fakes, and insist that the original Soviet version – Polish prisoners were shot by Germans in 1941 – is the correct one.[99][100][101] In late 2007 and early 2008, several Russian newspapers, including Rossiyskaya Gazeta, Komsomolskaya Pravda and Nezavisimaya Gazeta printed stories that implicated the Nazis for the crime, spurring concern that this was done with the tacit approval of the Kremlin.[101] As a result, the Polish Institute of National Remembrance decided to open its own investigation.[3]

On 4 February 2010 the Prime Minister of Russia, Vladimir Putin, invited his Polish counterpart, Donald Tusk, to attend a Katyn memorial in April.[102] The visit took place on 7 April 2010, when Tusk and Putin together commemorated the 70th anniversary of the massacre.[103] Before the visit, the 2007 film Katyń was shown on Russian state television for the first time. The Moscow Times commented that the film's premiere in Russia was likely a result of Putin's intervention.[104] On 10 April 2010, an aircraft carrying Polish President Lech Kaczyński with his wife and 87 other politicians and high-ranking army officers crashed in Smolensk, killing all 96 aboard the aircraft.[105] The passengers were to attend a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the Katyn massacre. The catastrophe has had major echoes in the international and notably Russian press, prompting, in particular, a rebroadcast of Katyń on Russian television.[106] The Polish President, Lech Kaczyński was to deliver a speech at the formal commemorations. The speech was to honour the victims, highlight the significance of the massacres in the context of post-war communist political history, as well as stress the need for Polish–Russian relations to focus on reconciliation. Although the speech was never delivered, it has been published with a narration in the original Polish[107] and a translation has also been made available in English.[108]

On 21 April 2010, it was reported that the Russian Supreme Court ordered the Moscow City Court to hear an appeal in an ongoing Katyn legal case.[109] A civil rights group, Memorial, said the ruling could lead to a court decision to open up secret documents providing details about the killings of thousands of Polish officers.[109] On 8 May 2010, Russia handed over to Poland 67 volumes of the "criminal case No.159," launched in the 1990s to investigate the Soviet-era mass killings of Polish officers. The copies of 67 volumes, each having about 250 pages, were packed in six boxes. With each box weighting approximately 12 kg (26.5 lbs), the total weight of all the documents stood at about 70 kg (153 lbs). Russian President Dmitry Medvedev handed one of the volumes to the acting Polish president, Bronislaw Komorowski. Medvedev and Komorowski agreed that the two states should continue their efforts in revealing the truth over the tragedy. The Russian president reiterated that Russia would continue declassifying documents on the Katyn massacre. The acting Polish president said that Russia's move might lay a good foundation for improving bilateral relations.[110]

In November 2010, the State Duma (lower house of the Russian parliament) passed a resolution declaring that long-classified documents "showed that the Katyn crime was carried out on direct orders of Stalin and other Soviet officials". The declaration also called for the massacre to be investigated further in order to confirm the list of victims. Members of the Duma from the Communist Party denied that the Soviet Union had been to blame for the Katyn massacre and voted against the declaration.[11] On December 6, 2010, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev promised the whole truth about the massacre, stating "Russia has recently taken a number of unprecedented steps towards clearing up the legacy of the past. We will continue in this direction."[111]

In art and literature

The Katyn massacre is a major plot element in many works of culture, for example, in the W.E.B. Griffin novel The Lieutenants, which is part of the Brotherhood of War series, as well as in the Robert Harris novel Enigma and the film of the same name. James R. Benn's Rag and Bone (Billy Boyle series) uses the Katyn Massacre as a central plot element. Polish poet Jacek Kaczmarski has dedicated one of his sung poems to this event.[112] In a bold political statement for the height of the Cold War, Dušan Makavejev used original Nazi footage in his 1974 film Sweet Movie. The Polish composer Andrzej Panufnik wrote an orchestral score in 1967 called "Katyn Epitaph" in memory of the massacre.

In 2000, US filmmaker Steven Fischer produced a public service announcement titled Silence of Falling Leaves honoring the fallen soldiers, consisting of images of falling autumn leaves with a sound track cutting to a narration in Polish by the Warsaw-born artist Bozena Jedrzejczak. It was honored with an Emmy nomination.[113]

The Academy Honorary Award recipient Polish film director Andrzej Wajda, whose father, Captain Jakub Wajda, was murdered in the NKVD prison of Kharkov, has made a film depicting the event, Katyn. The film recounts the fate of some of the women—mothers, wives and daughters—of the Polish officers slaughtered by the Soviets. Some Katyn Forest scenes are re-enacted. The screenplay is based on Andrzej Mularczyk's book Post mortem—the Katyn story. The film was produced by Akson Studio, and released in Poland on 21 September 2007. In 2008 it was nominated for an Academy Award for the Best Foreign Language Film.

In 2008, British historian Laurence Rees produced a 6-hour BBC / PBS television documentary series entitled World War II Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West. The Katyn massacre was a central theme.[114][115]

Memorials

Several statues in memory of the massacre have been erected worldwide. In the UK, during the Cold War, plans to build a major Katyn monument were objected to by the British government.[116][117][118] A monument was finally unveiled on 18 September 1976 at the Gunnersbury Cemetery amid controversy.[118][119] Soviet Union did not want the Katyn massacre to be remembered, and demanded that the British government prevent the erection of the monument.[118][120][e] The British government did not want to antagonize the Soviets, and the construction of the monument was delayed by many years.[116][117] When the local community secured the right for the monument to be put there, no government representative was present at the ceremony (although representative of the British Conservative Party opposition were present).[116][117][118] Another memorial in the UK was erected three years later, in 1979, in Cannock Chase, Staffordshire.[121]

In the USA, a golden statue, known as the National Katyn Massacre Memorial, is located in Baltimore, Maryland, on Aliceanna Street at Inner Harbor East.[122] Polish-Americans in Detroit erected a small white-stone memorial in the form of a cross with plaque at the St. Albertus Roman Catholic Church.[123] A statue commemorating the massacre is erected at Exchange Place on the Hudson River in Jersey City, New Jersey.[124]

In Canada, a large metal sculpture has been erected in the Polish community of Roncesvalles in Toronto, Ontario, to commemorate the killings.[125]

In South Africa, a memorial in Johannesburg commemorates the victims of Katyn as well as South African and Polish airmen who flew missions to drop supplies for the Warsaw Uprising.[126]

In Ukraine, a memorial complex was erected to honor the over 4300 officer victims of the Katyn massacre murdered in Pyatykhatky, 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) north of Kharkiv in Ukraine; the memorial complex lies in a corner of a former resort home for NKVD officers. Children had discovered hundreds of Polish officer buttons whilst playing on the site.[127] After excavation, the bodies were reburied with an alley of plaques, one for each of the officers shot there, stating their name, rank and town of origin.

In Russia, in 2000, the memorial at the Katyn war cemetery was opened.[128][129] Previously, the site featured a monument dedicated to the "victims of the Hitlerites."[128]

In Poland, in the city of Wrocław, a composition by Polish sculptor Tadeusz Tchorzewski unveiled in 2000, in a park east of the centre (near the city's Racławice Panorama building), is dedicated to those killed at Katyn. It shows the 'Matron of the Homeland' despairing over a dead soldier, whilst on a separate higher plinth the angel of death looms over, leaning forward on a sword.[130]

See also

- 1945 Augustów roundup, sometimes known as the "Little Katyn massacre"

- NKVD prisoner massacres

- Soviet repressions of Polish citizens (1939–1946)

- World War II crimes in Poland

Notes

a ^ Template:Ru icon Text of the original TASS communiqué released on April 14, 1990 as well as the subsequent cover-up.

b ^ Template:Ru icon Записка председателя КГБ при СМ СССР А.Н. Шелепина Н.С. Хрущеву о ликвидации всех учетных дел на польских граждан, расстрелянных в 1940 г. с приложением проекта постановления Президиума ЦК КПСС. 3 марта 1959 г. Рукопись. РГАСПИ. Ф.17. Оп.166. Д.621. Л.138-139., (Aleksandr Shelepin's 3 March 1959 note to Khrushchev, with information about the execution of 21,857 Poles and with the proposal to destroy their personal files.) retrieved on 12 December 2010. English translation is available in Katyń Justice Delayed or Justice Denied?.

c ^ Template:Ru icon/Template:En icon Excerpt from protocol No. 13 of the Politburo of the Central Committee meeting, shooting order of 5 March 1940, last accessed on 12 April 2010, original in Russian with English translation

d ^ Template:Ru icon Докладная записка наркома внутренних дел СССР Л.П. Берии И.В. Сталину с предложением поручить НКВД СССР рассмотреть в особом порядке дела на польских граждан, содержащихся в лагерях для военнопленных НКВД СССР и тюрьмах западных областей Украины и Белоруссии. Март 1940 г. Подлинник. РГАСПИ. Ф.17. Оп.166. Д.621. Л.130-133. Retrieved from the website "Архивы России" (Archives of Russia) on 12 December 2010.

e ^ Politburo Resolution and Instruction for the Soviet Ambassador in London Regarding the Projected Katyn Monument (Excerpt) 2 March 1973, Moscow

f ^ Among them Maj. Gen. Alexandre Chkheidze, who was handed over to the USSR by Nazi Germany per the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact;[131]

References

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. Stalin's Genocides (Human Rights and Crimes against Humanity). Princeton University Press, 2010. p. 92. ISBN 0-691-14784-1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field". "Studies in Intelligence", Winter 1999–2000. Retrieved on 10 December 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre, Małgorzata Kużniar-Plota, Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, Warsaw 30 November 2004

- ^ Timothy Snyder (12 October 2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. p. 140. ISBN 9780465002399. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Bożena Łojek (2000). Muzeum Katyńskie w Warszawie. Agencja Wydawm. CB Andrzej Zasieczny. p. 174. ISBN 9788386245857. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Michael Balfour, Propaganda in War 1939-1945: Organisation, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany, p332 ISBN 0-7100-0193-2

- ^ BBC News: "Russia to release massacre files", 16 December 2004

- ^ Geoffrey Roberts (2006). Stalin's wars: from World War to Cold War, 1939-1953. Yale University Press. p. 171. ISBN 9780300112047. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ "Russian, Polish Leaders To Mark Katyn Anniversary". RFE/RL, 07 April 2010.

- ^ a b A statement on investigation of the "Katyn crime" in Russia by the "Memorial" human rights society. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Russian parliament condemns Stalin for Katyn massacre", BBC News, 26 November 2010.

- ^ Ernest R. May, Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France (I. B. Tauris, 2000), p. 93

- ^ David Murray Horner, Robin Havers, The Second World War: Europe, 1939-1943 (Taylor & Francis, 2003), p. 34

- ^ Nicholas Werth, "A state against its people: violence, repression and terror in the Soviet Union" in Stéphane Courtois; Mark Kramer (15 October 1999). Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression. Harvard University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780674076082. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Alfred J. Rieber (2000). Forced migration in Central and Eastern Europe, 1939-1950. Psychology Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 9780714651323. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Mikhail Meltiukhov, Отчёт Украинского и Белорусского фронтов Красной Армии, p. 367.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Simon-Dubnow-Institut für Jüdische Geschichte und Kultur (2007). Shared history, divided memory: Jews and others in Soviet-occupied Poland, 1939-1941. Leipziger Universitätsverlag. p. 180. ISBN 9783865832405. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Template:Pl icon "ustawa z dnia 9 kwietnia 1938 r. o powszechnym obowiązku wojskowym (Act of 9 April 1938, on Compulsory Military Duty)". Dziennik Ustaw. 25 (220). 1938.

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon Cezary Gmyz, [1,8 mln polskich ofiar Stalina http://www.rp.pl/artykul/365363.html 1,8 mln polskich ofiar Stalina], rp.pl, 18-09-2009

- ^ a b AFP/Expatica, Polish experts lower nation's WWII death toll, expatica.com, 30 August 2009

- ^ a b Tomasz Szarota and Wojciech Materski (ed.), Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami, Warszawa, IPN 2009, ISBN 978-83-7629-067-6 (Introduction reproduced here)

- ^ Norman Davies (September 2008). No Simple Victory: World War II in Europe, 1939-1945. Penguin. p. 292. ISBN 9780143114093. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ {{cite book|author=Tadeusz Piotrowski|title=The Polish Deportees of World War II: Recollections of Removal to the Soviet Union and Dispersal Throughout the World|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9Kefzi0_vwIC&pg=PA4%7Caccessdate=16 June 2011|date=September 2007|publisher=McFarland|isbn=9780786432585|page=4}

- ^ a b c "The grave unknown elsewhere or any time before ... Katyń – Kharkov – Mednoe". Retrieved on 10 December 2005. Article includes a note that it is based on a special edition of a "Historic Reference-Book for the Pilgrims to Katyń – Kharkow – Mednoe" by Jędrzej Tucholski

- ^ a b Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780300108514. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Zawodny, Janusz K., Death in the Forest: The Story of the Katyn Forest Massacre, University of Notre Dame Press, 1962, ISBN 0-268-00849-3 partial html online. P. 77

- ^ Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. p. 81. ISBN 9780300108514. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Катынь. Пленники необъявленной войны. сб.док. М., МФ "Демократия": 1999, сс.20–21, 208–210.

- ^ Яжборовская, И. С.; Яблоков, А. Ю.; Парсаданова, B.C. (2001). "ПРИЛОЖЕНИЕ: Заключение комиссии экспертов Главной военной прокуратуры по уголовному делу № 159 о расстреле польских военнопленных из Козельского, Осташковского и Старобельского спецлагерей НКВД в апреле—мае 1940 г". Катынский синдром в советско-польских и российско-польских отношениях (in Russian) (1st ed.). ISBN 978-5-8243-1087-0. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Archie Brown (9 June 2009). The rise and fall of communism. HarperCollins. p. 140. ISBN 9780061138799. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Gerhard Weinberg, A World At Arms, p. 107. Referenced by Weinberg to Akten zur deutschen auswärtigen Politik D, 8, No. 657, n 2

- ^ a b c Parrish, Michael (1996). The Lesser Terror: Soviet state security, 1939–1953. Westport, CT: Praeger Press. pp. 324, 325. ISBN 0-275-95113-8.

- ^ Andrzej Leszek Szcześniak, ed. (1989). Katyń; lista ofiar i zaginionych jeńców obozów Kozielsk, Ostaszków, Starobielsk. Warsaw, Alfa. p. 366. ISBN 83-7001-294-9., Adam Moszyński, ed. (1989). Lista katyńska; jeńcy obozów Kozielsk, Ostaszków, Starobielsk i zaginieni w Rosji Sowieckiej. Warsaw, Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne. p. 336. ISBN 83-85028-81-1., Jędrzej Tucholski (1991). Mord w Katyniu; Kozielsk, Ostaszków, Starobielsk: lista ofiar. Warsaw, Pax. p. 987. ISBN 83-211-1408-3., Kazimierz Banaszek (2000). Kawalerowie Orderu Virtuti Militari w mogiłach katyńskich. Wanda Krystyna Roman, Zdzisław Sawicki. Warsaw, Chapter of the Virtuti Militari War Medal & RYTM. p. 351. ISBN 83-87893-79-X., Maria Skrzyńska-Pławińska, ed. (1995). Rozstrzelani w Katyniu; alfabetyczny spis 4410 jeńców polskich z Kozielska rozstrzelanych w kwietniu-maju 1940, według źródeł sowieckich, polskich i niemieckich. Stanisław Maria Jankowski. Warsaw, Karta. p. 286. ISBN 83-86713-11-9., Maria Skrzyńska-Pławińska, ed. (1996). Rozstrzelani w Charkowie; alfabetyczny spis 3739 jeńców polskich ze Starobielska rozstrzelanych w kwietniu-maju 1940, według źródeł sowieckich i polskich. Ileana Porytskaya. Warsaw, Karta. p. 245. ISBN 83-86713-12-7., Maria Skrzyńska-Pławińska, ed. (1997). Rozstrzelani w Twerze; alfabetyczny spis 6314 jeńców polskich z Ostaszkowa rozstrzelanych w kwietniu-maju 1940 i pogrzebanych w Miednoje, według źródeł sowieckich i polskich. Ileana Porytskaya. Warsaw, Karta. p. 344. ISBN 83-86713-18-6.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Dmitri Stepanovich Tokariev (1994). Zeznanie Tokariewa. Anatoliy Ablokov, Fryderyk Zbiniewicz. Zeszyty Katyńskie 1426-4064 nr 3: Warsaw, Niezależny Komitet Historyczny Badania Zbrodni Katyńskiej. p. 71.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link), also in Aleksander Gieysztor, Rudolf Germanovich Pikhoya, ed. (1995). Katyń; dokumenty zbrodni. Wojciech Materski, Aleksandra Belerska. Warsaw, Trio. pp. 547–567. ISBN 83-85660-62-3 + ISBN 83-86643-80-3.{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ See for instance: Template:Pl icon Barbara Polak (2005). "Zbrodnia katyńska" (PDF). Biuletyn IPN: 4–21. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Simon Sebag Montefiore. Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 1-4000-4230-5 p. 334: "He brought a butcher's leather apron and cap which he put on when he began one of the most prolific acts of mass murder by one individual, killing 7,000 in precisely twenty-eight nights, using a German Walther pistol to prevent future exposure."

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon various authors (collection of documents) (1962). Zbrodnia katyńska w świetle dokumentów. London: Gryf. pp. 16, 30, 257.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Pl icon cheko, Polish Press Agency (2007). "Odkryto grzebień z nazwiskami Polaków pochowanych w Bykowni". Gazeta Wyborcza (2007–09–21). Retrieved 2007-09-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Zdzisław J. Peszkowski (2007). "Jedyna kobieta — ofiara Katynia (The only woman victim of Katyn)". Tygodnik Wileńszczyzny (10). Retrieved 2007-09-22.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Template:Pl icon Various authors. Biuletyn „Kombatant” nr specjalny (148) czerwiec 2003 Special Edition of Kombatant Bulletin No.148 6/2003 on the occasion of the Year of General Sikorski. Official publication of the Polish government Agency of Combatants and Repressed

- ^ Template:Ru icon Ромуальд Святек, "Катынский лес", Военно-исторический журнал, 1991, №9, ISSN 0042-9058

- ^ Roman Brackman (2001). The secret file of Joseph Stalin: a hidden life. Psychology Press. p. 358. ISBN 9780714650500. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon Barbara Polak (2005). "Zbrodnia katyńska" (PDF). Biuletyn IPN: 4–21. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Adam Basak (1993). Historia pewnej mistyfikacji: zbrodnia katyńska przed Trybunałem Norymberskim. Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. p. 37. ISBN 9788322908853. Retrieved 7 May 2011. (Also available at [1])

- ^ Michael Balfour, Propaganda in War 1939-1945: Organisation, Policies and Publics in Britain and Germany, p332-3 ISBN 0-7100-0193-2

- ^ David Engel (1993). Facing a holocaust: the Polish government-in-exile and the Jews, 1943-1945. UNC Press Books. p. 71. ISBN 9780807820698. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 130. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Goebbels, Joseph. The Goebbels Diaries (1942–1943). Translated by Louis P. Lochner. Doubleday & Company. 1948

- ^ Zawodny, Janusz K., Death in the Forest: The Story of the Katyn Forest Massacre, University of Notre Dame Press, 1962, ISBN 0-268-00849-3 partial html online. P. 15

- ^ a b c Davies, Norman. "Europe: A History". HarperCollins, 1998. ISBN 0-06-097468-0.

- ^ Official statement of the Polish government, on 17 April 1943, published in London on 18 April; last accessed on 14 April 2010, English translation of the Polish document

- ^ Roy Francis Leslie (1983). The History of Poland since 1863. Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 9780521275019.

- ^ Soviet Note of 25 April 1943, severing unilaterally Soviet-Polish diplomatic relations, last accessed on 14 April 2010, English translation of the Russian document

- ^ Martin Dean (9 March 2003). Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-44. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 144. ISBN 9781403963710. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Stanley Sandler (2002). Ground warfare: an international encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 808. ISBN 9781576073445.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. pp. 226–229. ISBN 9780300108514. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ Dennis J. Dunn (1998). Caught between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's ambassadors to Moscow. University Press of Kentucky. p. 184. ISBN 9780813120232. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ David Carlton (2000). Churchill and the Soviet Union. Manchester University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780719041075. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Correspondence between the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Presidents of the USA and the Prime Ministers of Great Britain during the Great Patriotic War of 1941 - 1945, document №. 151, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1953, USSR

- ^ Winston Churchill (11 April 1986). The Hinge of Fate. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 680. ISBN 9780395410585. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ Ron Jeffery, "Red Runs the Vistula", Nevron Associates Publ., Manurewa, Auckland, New Zealand 1985

- ^ "Book "Red Runs the Vistula"". Antoranz.net. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- ^ a b National Archives and Records Administration, documents related to Committee to Investigate and Study the Facts, Evidence, and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre (1951–52) online, last accessed on 14 April 2010. Also, Select Committee of the US Congress final report: "The Katyn Forest Massacre," House Report No. 2505, 82nd Congress, 2nd Session (22 December 1952) online pdf, unofficial reproduction of the relevant parts.

- ^ "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Template:Ru icon I.S.Yazhborovskaja, A.Yu.Yablokov, V.S.Parsadanova, Катынский синдром в советско-польских и российско-польских отношениях (The Katyn Syndrome in Soviet-Polish and Russian-Polish Relations), Moscow, ROSSPEN, 2001, ISBN 5-8243-0197-2, pp. 336–337. (paragraph preceding footnote [40] in the web version). A review of this book appeared as Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1467-9434.2005.00389.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1467-9434.2005.00389.xinstead. - ^ S. S. Alderman, "Negotiating the Nuremberg Trial Agreements, 1945," in Raymond Dennett and Joseph E. Johnson, edd., Negotiating With the Russians (Boston, MA: World Peace Foundation, [1951]), p. 96

- ^ Excerpts of Nuremberg archives: Nizkor.org – Fifty-Ninth Day: Thursday, 14 February 1946 (Part 7 of 15). Retrieved 2 January 2006.

- ^ Bernard A. Cook (2001). Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 71. ISBN 9780815340584. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- ^ As described by Iona Nikitchenko, one of the judges and a military magistrate having been involved in Stalin's show trials, "the fact that the Nazi chiefs are criminals was already established [by the declarations and agreements of the Allies]. The role of this court is thus limited to determine the precise culpability of each one [charged]". in: Nuremberg Trials, Leo Kahn, Bellantine, N.Y., 1972, p.26.

- ^ Silitski, Vitali. "A Partisan Reality Show". Transitions Online, 11 May 2005. ISSN 1214–1615 Parameter error in {{issn}}: Invalid ISSN.

- ^ Coatney, Louis Robert (1993). The Katyn Massacre (A Master of Arts Thesis). Macomb: Western Illinois University. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Schemann, Serge (1985). "SOLDIERS STORY' SHARES PRIZE AT MOSCOW FILM FESTIVAL". New York Times: 10. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Matthew J. Ouimet (2003). The rise and fall of the Brezhnev Doctrine in Soviet foreign policy. UNC Press Books. p. 126. ISBN 9780807854112. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 9780300108514. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b RFE/RL Research Institute (1993). RFE/RL research report: weekly analyses from the RFE/RL Research Institute. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Inc. p. 24. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

One of the documents turned over to the Poles on 14 October was Shelepin's handwritten report from 1959

- ^ United Press International: Weeping Poles visit Katyn massacre site 30 October 1989

- ^ BBC News: Commemoration of Victims of Katyn Massacre, 1 November 1989

- ^ Associated Press: Brzezinski: Soviets Should Take Responsibility for Katyn Massacre 30 October 1989

- ^ "Judgment On Katyn". Time, 13 November 1989. Retrieved on 04 August 2008.

- ^ "CHRONOLOGY 1990; The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe." Foreign Affairs, 1990, pp. 212.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Polish government statement: Senate pays tribute to Katyn victims – 3/31/2005. Retrieved 2 January 2006. Template:Wayback

- ^ Polish government statement: IPN launches investigation into Katyn crime – 1/12/2004. Retrieved 2 January 2006.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Encyklopedia PWN, 'KATYŃ'. Retrieved on 14 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780300108514. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ POLISH–RUSSIAN FINDINGS ON THE SITUATION OF RED ARMY SOLDIERS IN POLISH CAPTIVITY (1919–1922). Official Polish government note about 2004 Rezmar, Karpus and Matvejev book. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Rezmer, Waldemar (2004). Krasnoarmieitsy v polskom plenu v 1919–1922 g. Sbornik dokumentov i materialov. Moscow: Federal Agency for Russian Archives.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 9780415338738. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Radio Free Europe, ...DESPITE POLAND'S STATUS AS 'KEY ECONOMIC PARTNER, Newsline Wednesday, 29 September 2004 Volume 8 Number 185. Retrieved 2 January 2006.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Ответ ГВП на письмо общества «Мемориал», 2005

- ^ Guardian Unlimited, "Russian victory festivities open old wounds in Europe", 29 April 2005, by Ian Traynor. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Warsaw Voice, "Katyn Resolution Adopted", 30 March 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2006.

- ^ Template:Pl icon wiadomosci.gazeta.pl: "NKWD filmowało rozstrzelania w Katyniu", 17 July 2008

- ^ The Economist: "Dead leaves in the wind: Poland, Russia and history", Jun 19th 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Ewa Siedlecka (2008-11-25). "Ombudsman to Join Katyn Claims in Strasbourg Court". Wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Юрий Изюмов. "Катынь не по Геббельсу. Беседа с Виктором Илюхиным." ("Досье", №40, 2005 г.)]

- ^ Template:Ru icon Юрий Мухин, "Антироссийская подлость"

- ^ a b The Economist: "In denial: Russia revives a vicious lie", 7 Feb 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Easton, Adam (2010-02-04). "Russia's Putin invites Tusk to Katyn massacre event". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ "Putin Marks Soviet Massacre of Polish Officers". The New York Times. April 7, 2010.

- ^ The Moscow Times: "'Katyn' Film Premieres on State TV", 5 April 2010

- ^ "Polish President Lech Kaczynski dies in plane crash". BBC News. BBC. 10 April 2010. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Gazeta.pl: "Rosyjska telewizja państwowa wieczorem pokaże "Katyń" Wajdy", 11 April 2010

- ^ Template:Pl icon "Słowa które nie padły"

- ^ View From The Right "The Speech the Polish President was to give at the Katyn Memorial" (12 April 2010)

- ^ a b "Russian Court Ordered to Hear Appeal in Katyn Case". The New York Times. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Russia hands over volumes of Katyn massacre case to Poland". RIA Novosti. 9 May 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Medvedev promises whole truth behind Katyn massacre RIA Novosti, December 6, 2010.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Kaczmarski, Jacek. "Katyń". kaczmarski.art.pl, 29 August 1985. Retrieved on 05 August 2008.

- ^ "Balto. indie gets Emmy nod". Mddailyrecord.com. 2001-05-22. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ "– YouTube WWII Behind Closed Doors: Stalin, the Nazis and the West | Clip #1 | PBS". Youtube.com. 2009-04-25. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ Laurence Rees, World War II Behind Closed Doors, BBC Books, 2009, page 410

- ^ a b c Katyn in the Cold War, Foreign and Commonwealth Office

- ^ a b c Brian Crozier, The Katyn Massacre and Beyond, National Observer, No. 44, Autumn 2000 >

- ^ a b c d Anna M. Cienciala; Wojciech Materski (2007). Katyn: a crime without punishment. Yale University Press. pp. 243–245. ISBN 978-0-300-10851-4. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Hugh Meller (10 March 1994). London cemeteries: an illustrated guide and gazetteer. Scolar Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-85967-997-8. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ^ George Sanford (2005). Katyn and the Soviet massacre of 1940: truth, justice and memory. Psychology Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-415-33873-8. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ BBC News: "Katyn remembered at Cannock Chase on 70th anniversary ", 19 May 2010

- ^ "National Katyn Memorial Foundation". National Katyn Memorial Foundation, 08 October 2005. Retrieved on 04 August 2008.

- ^ "Polish-American Artist Among Victims of Plane Crash," 16 April 2010

- ^ "Katyn Memorial in Jersey City".

- ^ "Roncesvalles Village Commemorates Tragedy In Poland", Welcome to Roncesvalles Village, [2]. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ "Johannesburg Katyn Memorial".

- ^ Neal Ascherson. "An accident of history | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ a b Template:Pl icon RMF/PAP, Katyń: Otwarcie polskiego cmentarza wojennego, Interia.pl, 28 July 2000

- ^ Template:Pl icon Jagienka Wilczak, Rdza jak krew: Katyń, Charków, Miednoje, Polityka, 31/2010

- ^ "Wroclaw Statues — Monument to the Victims of the Katyń Massacre". Wroclaw.ivc.pl. Retrieved 2011-02-25.

- ^ Template:Pl icon Jakubowska, Justyna (2007). "Prezydenci Polski i Gruzji odsłonili pomnik gruzińskich oficerów w Wojsku Polskim". kaukaz.pl. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

Further reading

- Cienciala, Anna M.; S. Lebedeva, Natalia; Materski, Wojciech, eds. (2008). Katyn: A Crime Without Punishment. Annals of Communism Series. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10851-6.

- Komorowski, Eugenjusz A.; Gilmore, Joseph L. (1974). Night Never Ending. Avon Books.

- Paul, Allen (2010). Katyń: Stalin's Massacre and the Triumph of Truth. Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, IL. ISBN 978-0-87580-634-1.

- Paul, Allen (1996). Katyń: Stalin's massacre and the seeds of Polish Resurrection publisher = Annapolis, Md., Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-670-1.

{{cite book}}: Missing pipe in:|title=(help) - Paul, Allen (1991). Katyn: The Untold Story of Stalin's Polish Massacre. Scribner Book Company. ISBN 0-684-19215-2.

- Sandford, George. "The Katyn Massacre and Polish–Soviet relations 1941–1943" (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 41 (1): 95–111.

- Swianiewicz, Stanisław (2000) [1976]. W cieniu Katynia. Borealis Pub. ISBN 1-894255-16-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Zaslavsky, Victor (2008). Class Cleansing: The Katyn Massacre. Kizer Walker (trans.). Telos Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-914386-41-4.

External links

- Мемориал “Катынь” (Katyn Memorial Museum, official website)

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) (UK) "The Katyn Massacre: A Special Operations Executive perspective" Historical Papers Official documents, Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Archived by National Archives (UK) on February 5, 2008

- Adam Scrupski "Historians Have Yet to Face Up to the Implications of the Katyn Massacre" History News Network May 17, 2004

- Benjamin B. Fischer "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field" Studies in Intelligence Winter, 1999–2000.

- Louis Robert Coatney The Katyn Massacre: An Assessment of its Significance as a Public and Historical Issue in the United States and Great Britain, 1940–1993 (MA Thesis) Western Illinois University, 1993.

- Wacław Radziwinowicz "Katyn Victims Near Kharkov Covered with Lime," trans. Marcin Wawrzyńczak, Gazeta Wyborcza, August 10, 2009.

- Timothy Snyder "Russia’s Reckoning with Katyń" NYR Blog, New York Review of Books, December 1, 2010.

- "Truth Is Out: Katyn massacre carried out on Stalin's direct orders" Russia Today (official YouTube channel), November 26, 2010.