Latin: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with 'ITS ALL ABOUT THE CHICKEN POP ' |

StewdioMACK (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by Cheesychopsticks (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG. (TW) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for||Latins|Latin (disambiguation)}} |

|||

ITS ALL ABOUT THE CHICKEN POP |

|||

{{redirect-distinguish|Roman language|Romance languages|Romanesco language|Romanian language|Romani language}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2012}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{Infobox language |

|||

| name = Latin DON'T EDIT THIS |

|||

| nativename = ''Lingua latīna'' |

|||

| pronunciation = {{IPA-la|laˈtiːna|}} |

|||

| states = {{ublist|class=nowrap |[[Latium]] |[[Roman Kingdom]]{{\}}[[Roman Republic|Republic]]{{\}}[[Roman Empire|Empire]] |{{hlist|[[Medieval Europe]]|[[Early modern Europe]]}} |[[Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia]] {{smaller|([[lingua franca]])}} |[[Vatican City]]}} |

|||

| ethnicity = [[Latins (Italic tribe)|Latins]] |

|||

| era = [[Vulgar Latin]] developed into [[Romance languages]], 6th to 9th centuries; the formal language continued as the scholarly [[lingua franca]] of Catholic countries medieval Europe and as the [[liturgical language]] of the [[Roman Catholic Church]]. |

|||

| familycolor = Indo-European |

|||

| fam2 = [[Italic languages|Italic]] |

|||

| fam3 = [[Latino-Faliscan languages|Latino-Faliscan]] |

|||

| script = [[Latin alphabet]] <!-- needed to prevent default link to Latin script--> |

|||

| nation = {{ublist|class=nowrap |{{flag|Sovereign Military Order of Malta}} |{{VAT}} }} |

|||

| agency = {{ublist|class=nowrap |Antiquity: Roman schools of grammar/rhetoric<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Schools |encyclopedia=Britannica |edition=1911}}</ref> |Today: [[Pontifical Academy for Latin]]}} |

|||

| iso1=la |iso2=lat |iso3=lat |

|||

| glotto=lati1261 |glottorefname=Latin |

|||

| lingua=51-AAB-a |

|||

| image = Rome Colosseum inscription 2.jpg |

|||

| imagesize = 300px |

|||

| imagecaption = Latin inscription in the [[Colosseum]] |

|||

| map = Roman Empire map.svg |

|||

| mapcaption = Map indicating the greatest extent of the Roman Empire ([[Circa|c.]] 117 AD) and the area governed by Latin speakers (dark green). Many languages other than Latin, most notably Greek, were spoken within the empire. |

|||

| map2 = RomanceLanguages.png |

|||

| mapcaption2 = Range of the Romance languages, the modern descendants of Latin, in Europe. |

|||

| notice = IPA |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Latin''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|l|æ|t|ɪ|n|audio=En-us-latin.ogg}}; Latin: {{lang|la|''lingua latīna''}}, {{IPA-la|ˈlɪŋɡʷa laˈtiːna|IPA}}) is an [[Classical antiquity|ancient]] [[Italic languages|Italic language]]<ref>{{cite book |title=A companion to Latin studies |first=John Edwin |last=Sandys |location=Chicago |publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]] |year=1910 |pages=811–812}}</ref> originally spoken by the [[List of ancient Italic peoples|Italic]] [[Latins (Italic tribe)|Latins]] in [[Latium]] and [[Ancient Rome]]. Along with most [[Languages of Europe|European languages]], it is a descendant of the ancient [[Proto-Indo-European language]]. Influenced by the [[Etruscan language]] and using the [[Greek alphabet]] as a basis, it took form as what is recognizable as Latin in the [[Italian Peninsula]]. Modern [[Romance languages]] are continuations of dialectal forms ([[vulgar Latin]]) of the language. Additionally many students, scholars, and some members of the [[Minister (Christianity)|Christian clergy]] speak it fluently, and it is taught in primary, secondary and post-secondary educational institutions around the world.<ref>{{cite journal |title=A Dead Language That's Very Much Alive |url=http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/07/nyregion/07latin.html |first=Winnie |last=Hu |journal=New York Times |date=6 October 2008 |ref=harv}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=The New case for Latin |url=http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,90457,00.html |first=Mike |last=Eskenazi |journal=TIME |date=2 December 2000}}</ref> |

|||

Latin is still used in [[Neologism|the creation of new words]] in modern languages of many different families, including English, and largely in biological [[Taxonomy (biology)|taxonomy]]. Latin and its derivative Romance languages are the only surviving languages of the [[Italic languages|Italic language family]]. Other languages of the Italic branch were attested in the inscriptions of early Italy, but were assimilated to Latin during the [[Roman Republic]]. |

|||

The extensive use of elements from vernacular speech by the earliest authors and inscriptions of the Roman Republic make it clear that the original, unwritten language of the [[Roman Kingdom]] was an only partially deducible{{clarify|date=September 2013}} [[Colloquialism|colloquial]] form, the predecessor to [[Vulgar Latin]]. By the arrival of the late Roman Republic, a standard, literate form had arisen from the speech of the educated, now referred to as [[Classical Latin]]. Vulgar Latin, by contrast, was the more rapidly changing colloquial language, which was spoken throughout the empire.<ref>{{harvnb|Clark|1900|pp=1–3}}</ref> |

|||

Because of the [[Military history of ancient Rome|Roman conquests]], Latin spread to many [[Mediterranean Sea|Mediterranean]] and some northern European regions, and the dialects spoken in these areas, mixed to various degrees with the [[indigenous language]]s, developed into the modern [[Romance languages]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Bryson |first=Bill |year=1996 |title=The mother tongue: English and how it got that way |location=New York |publisher=Avon Books |pages=33–34 |isbn=0-14-014305-X}}</ref> Classical Latin slowly changed with the [[decline of the Roman Empire]], as education and wealth became ever scarcer. The consequent [[Medieval Latin]], influenced by various Germanic and proto-Romance languages until [[expurgation|expurgated]] by [[Renaissance]] scholars, was used as the language of international communication, scholarship, and science until well into the 18th century, when it began to be supplanted by [[vernacular]]s. |

|||

Latin is a highly [[fusional language|inflected language]], with three distinct [[Grammatical gender|genders]], five to seven [[Grammatical case|noun cases]], four [[Grammatical conjugation|verb conjugations]], six [[Grammatical tense|tenses]], three [[Grammatical person|persons]], three [[Grammatical mood|moods]], two [[Voice (grammar)|voices]], two [[Grammatical aspect|aspects]], and two [[Grammatical number|numbers]]. |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

The Latin language has been passed down through various forms. |

|||

=== Inscriptions === |

|||

Some inscriptions have been published in an internationally agreed-upon, monumental, multivolume series termed the "''[[Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum]]'' (CIL)". Authors and publishers vary, but the format is about the same: volumes detailing inscriptions with a critical apparatus stating the [[provenance]] and relevant information. The reading and interpretation of these inscriptions is the subject matter of the field of [[epigraphy]]. About 270,000 inscriptions are known. |

|||

=== Literature === |

|||

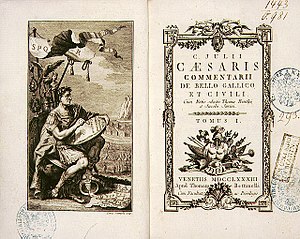

[[File:Commentarii de Bello Gallico.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Julius Caesar]]'s [[Commentarii de Bello Gallico]] is one of the most famous classical Latin texts of the Golden Age of Latin. The unvarnished, journalistic style of this [[Patrician (ancient Rome)|patrician]] general has long been taught as a model of the urbane Latin officially spoken and written in the floruit of the [[Roman republic]].]] |

|||

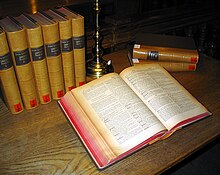

The works of several hundred ancient authors who wrote in Latin have survived in whole or in part, in substantial works or in fragments to be analyzed in [[philology]]. They are in part the subject matter of the field of [[Classics]]. Their works were published in [[manuscript]] form before the invention of printing and now exist in carefully annotated printed editions such as the [[Loeb Classical Library]], published by [[Harvard University Press]], or the [[Oxford Classical Texts]], published by [[Oxford University Press]]. |

|||

[[Latin translations of modern literature]] such as ''[[The Hobbit]]'', ''[[Treasure Island]]'', ''[[Robinson Crusoe]]'', ''[[Paddington Bear]]'', ''[[Winnie the Pooh]]'', ''[[The Adventures of Tintin]]'', ''[[Asterix]]'', ''[[Harry Potter]]'', ''[[Walter the Farting Dog]]'', ''[[The Little Prince|Le Petit Prince]]'', ''[[Max und Moritz]]'', ''[[How the Grinch Stole Christmas]]'', ''[[The Cat in the Hat]]'', and a book of fairy tales, "fabulae mirabiles," are intended to garner popular interest in the language. Additional resources include phrasebooks and resources for rendering everyday phrases and concepts into Latin, such as [[Meissner's Latin Phrasebook]]. |

|||

=== Linguistics === |

|||

[[Latin influence in English]] has been significant at all stages of its insular development. In the medieval period, much borrowing from Latin occurred through ecclesiastical usage established by Saint [[Augustine of Canterbury]] in the sixth century, or indirectly after the [[Norman Conquest]] through the [[Anglo-Norman language]]. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, English writers cobbled together huge numbers of new words from Latin and Greek words. These were dubbed "[[inkhorn term]]s", as if they had spilled from a pot of ink. Many of these words were used once by the author and then forgotten. Some useful ones, though, survived, such as 'imbibe' and 'extrapolate'. Many of the most common [[polysyllabic]] English words are of Latin origin, through the medium of [[Old French]]. |

|||

Due to the influence of Roman governance and [[Roman technology]] on the less developed nations under Roman dominion, those nations adopted Latin phraseology in some specialized areas, such as science, technology, medicine, and law. For example, [[Linnaean taxonomy|the Linnaean system]] of plant and animal classification was heavily influenced by ''[[Natural History (Pliny)|Historia Naturalis]]'', an encyclopedia of people, places, plants, animals, and things published by [[Pliny the Elder]]. Roman medicine, recorded in the works of such physicians as [[Galen]], established that today's [[medical terminology]] would be primarily derived from Latin and Greek words, the Greek being filtered through the Latin. Roman engineering had the same effect on [[scientific terminology]] as a whole. Latin law principles have survived partly in a long [[list of legal Latin terms]]. |

|||

Many [[international auxiliary language]]s have been heavily influenced by Latin. [[Interlingua]], which lays claim to a sizable following, is sometimes considered a simplified, modern version of the language. [[Latino sine Flexione]], popular in the early 20th century, is Latin with its inflections stripped away, among other grammatical changes. |

|||

=== Education === |

|||

[[File:Latin dictionary.jpg|thumb|left|A multi-volume Latin dictionary in the [[University Library of Graz]]]] |

|||

Throughout European history, an education in the [[Classics]] was considered crucial for those who wished to join literate circles. [[Instruction in Latin]] is an essential aspect of Classics. In today's world, a large number of Latin students in America learn from ''Wheelock's Latin: The Classic Introductory Latin Course, Based on Ancient Authors''. This book, first published in 1956,<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.wheelockslatin.com/ | title=The Official Wheelock's Latin Series Website | first=Richard A. | last=LaFleur | year=2011 | publisher=The Official Wheelock's Latin Series Website}}</ref> was written by [[Frederic M. Wheelock]], who received a PhD from Harvard University. ''Wheelock's Latin'' has become the standard text for many American introductory Latin courses. |

|||

The [[Living Latin]] movement attempts to teach Latin in the same way that living languages are taught, i.e., as a means of both spoken and written communication. It is available at the Vatican, and at some institutions in the U.S., such as the [[University of Kentucky]] and [[Iowa State University]]. The British [[Cambridge University Press]] is a major supplier of Latin textbooks for all levels, such as the [[Cambridge Latin Course]] series. It has also published a subseries of children's texts in Latin by Bell & Forte, which recounts the adventures of a mouse called [[Minimus]]. |

|||

In the [[United Kingdom]], the [[Classical Association]] encourages the study of antiquity through various means, such as publications and grants. The [[University of Cambridge]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cambridgescp.com/ |title=University of Cambridge School Classics Project - Latin Course |publisher=Cambridgescp.com |accessdate=2014-04-23}}</ref> the [[Open University]] (OU),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www3.open.ac.uk/study/undergraduate/course/a297.htm |title=Open University Undergraduate Course - Reading classical Latin |publisher=.open.ac.uk |accessdate=2014-04-23}}</ref> a number of prestigious independent schools, for example [[Eton College|Eton]] and [[Harrow School|Harrow]], and Via Facilis,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thelatinprogramme.co.uk/ |title=The Latin Programme – Via Facilis |publisher=Thelatinprogramme.co.uk |accessdate=2014-04-23}}</ref> a London based charity, do still run Latin courses. In the [[United States]] and [[Canada]], the [[American Classical League]] supports every effort to further the study of classics. Its subsidiaries include the [[National Junior Classical League]] (with more than 50,000 members), which encourages high school students to pursue the study of Latin, and the [[National Senior Classical League]], which encourages students to continue their study of the classics into college. The league also sponsors the [[National Latin Exam]]. Classicist [[Mary Beard (classicist)|Mary Beard]] wrote in ''[[The Times Literary Supplement]]'' in 2006 that the reason for learning Latin is because of what was written in it.<ref name="timesonline train the brain">{{cite web | url=http://timesonline.typepad.com/dons_life/2006/07/does_latin_trai.html | title=Does Latin "train the brain"? | work=[[The Times Literary Supplement]] | date=10 July 2006 | accessdate=20 December 2011 | author=Beard, Mary | quote=No, you learn Latin because of what was written in it – and because of the sexual side of life direct access that Latin gives you to a literary tradition that lies at the very heart (not just at the root) of Western culture. | authorlink=Mary Beard (classicist)}}</ref> |

|||

=== Official status === |

|||

Latin has been and or is the official language of European states: |

|||

* {{flag|Croatia}} - Latin was the official language of Croatian Parliament (Sabor) from the 13th until the 19th century (1847). The oldest preserved records of the parliamentary sessions (Congregatio Regni totius Sclavonie generalis)—held in Zagreb (Zagabria), Croatia—date from 19 April 1273. An extensive [[Croatian Latin literature]] exists. |

|||

* {{flag|Poland}} - officially recognized and widely used<ref>Who only knows Latin can go across the whole Poland from one side to the other one just like he was at his own home, just like he was born there. So great happiness! I wish a traveler in England could travel without knowing any other language than Latin!, Daniel Defoe, 1728</ref><ref>Anatol Lieven, The Baltic Revolution: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Path to Independence, Yale University Press, 1994, ISBN 0-300-06078-5, Google Print, p.48</ref><ref>Kevin O'Connor, Culture And Customs of the Baltic States, Greenwood Press, 2006, ISBN 0-313-33125-1, Google Print, p.115</ref><ref>Karin Friedrich et al., The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7, Google Print, p.88</ref> between the 9th and 18th centuries, commonly used in foreign relations and popular as a second language among some of the nobility<ref name="Friedrich" >Karin Friedrich et al., ''The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772'', Cambridge University |

|||

Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-58335-7, [http://books.google.com/books?id=qsBco40rMPcC&pg=PA88&dq=Latin+language+szlachta&as_brr=3&ei=J44rR5_XFZXC7AK4xeGVBQ&sig=3ecP0DjPuCLnTaEdVI76Ck8xSE8 Google Print, p.88]</ref> |

|||

* {{flag|Holy See}} - used in the [[diocese]], with [[Italian language|Italian]] being the official language of [[Vatican City]]<!--The Holy See uses Latin, but the Holy See is not Vatican City State.--> |

|||

== History of Latin == |

|||

{{Main|History of Latin}} |

|||

A number of historical phases of the language have been recognized, each distinguished by subtle differences in vocabulary, usage, spelling, morphology and syntax. There are no hard and fast rules of classification; different scholars emphasize different features. As a result, the list has variants, as well as alternative names. In addition to the historical phases, [[Ecclesiastical Latin]] refers to the styles used by the writers of the [[Roman Catholic Church]], as well as by Protestant scholars, from [[Late Antiquity]] onward. |

|||

After the Roman Empire in Western Europe fell, and Germanic kingdoms took its place, the Germanic people adopted Latin as a language more suitable to legal, and other more formal, expression.{{citation needed|date=June 2014}} |

|||

=== Old Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Old Latin}} |

|||

The earliest known form of Latin is [[Old Latin]], which was spoken from the [[Roman Kingdom]] to the middle [[Roman republic|Republican]] period, and is attested both in inscriptions and in some of the earliest extant Latin literary works, such as the comedies of [[Plautus]] and [[Terence]]. During this period, the [[Latin alphabet]] was devised from the [[Etruscan alphabet]]. The writing style later changed from an initial right-to-left or [[boustrophedon]]<ref>{{harvnb|Diringer|1996|pp=533–4}}</ref> to a left-to-right script.<ref>{{cite book|first=David |last=Sacks |year=2003 |title=Language Visible: Unraveling the Mystery of the Alphabet from A to Z |location=London |publisher= Broadway Books |page=80|isbn=0-7679-1172-5}}</ref> |

|||

=== Classical Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Classical Latin}} |

|||

During the late republic and into the first years of the empire, a new [[Classical Latin]] arose, a conscious creation of the orators, poets, historians and other [[literate]] men, who wrote the great works of [[classical literature]], which were taught in [[grammar]] and [[rhetoric]] schools. Today's instructional grammars trace their roots to these [[Roman school|schools]], which served as a sort of informal language academy dedicated to maintaining and perpetuating educated speech.<ref>{{cite book|page=3|title=From Latin to modern French with especial consideration of Anglo-Norman; phonology and morphology|first=Mildred K |last=Pope|authorlink=Mildred Pope|location=Manchester|publisher=Manchester university press|series=Publications of the University of Manchester, no. 229. French series, no. 6| year=1966}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Source book of the history of education for the Greek and Roman period|first=Paul|last=Monroe|location=London, New York|publisher=[[Macmillan & Co.]]|year=1902|pages=346–352}}</ref> |

|||

=== Vulgar Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Vulgar Latin|Late Latin}} |

|||

Philological analysis of Archaic Latin works, such as those of [[Plautus]], which contain snippets of everyday speech, indicates that a spoken language, [[Vulgar Latin]] (''sermo vulgi'' ("the speech of the masses") by [[Cicero]]), existed at the same time as the literate Classical Latin. This informal language was rarely written, so philologists have been left with only individual words and phrases cited by Classical authors, as well as those found as graffiti.<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|Wright|2000|pp=17–18}}</ref> |

|||

As vernacular Latin was free to develop on its own, there is no reason to suppose that the speech was uniform either diachronically or geographically. On the contrary, Romanized European populations developed their own dialects of the {{nowrap|language.<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|Wright|2000|p=8}}</ref>}} The [[Decline of the Roman Empire]] meant a deterioration in educational standards that brought about [[Late Latin]], a post-classical stage of the language seen in Christian writings of the time. This language was more in line with the everyday speech not only because of a decline in education, but also because of a desire to spread the word to the masses. |

|||

Despite dialect variation (which is found in any sufficiently widespread language) the languages of Spain, France, Portugal and Italy retained a remarkable unity in phonological forms and developments, bolstered by the stabilizing influence of their common Christian (Roman Catholic) culture. It was not until the [[Umayyad conquest of Hispania|Moorish conquest of Spain]] in 711 cut off communications between the major Romance regions that the languages began to diverge seriously.<ref>{{cite book|last=Pei|first=Mario|title=The story of Latin and the Romance languages|year=1976|publisher=Harper & Row|location=New York|isbn=0-06-013312-0|pages=76–81|edition=1st|coauthors=compiled,, ; Gaeng, arranged by Paul A.}}</ref> The Vulgar Latin dialect that would later become [[Romanian language|Romanian]] diverged somewhat more from the other varieties due to its being largely cut off from the unifying influences in the western part of the Empire. |

|||

One way to determine whether a Romance language feature was in Vulgar Latin is to compare it with its parallel in Classical Latin. If it was not preferred in classical Latin, then it most likely came from the invisible contemporaneous vulgar Latin. For example, Romance "horse" (cavallo/cheval/caballo/cavalo) came from Latin ''caballus''. However, classical Latin used ''equus''. ''Caballus'' therefore was most likely the spoken form ([[slang]]).<ref>{{harvnb|Herman|Wright|2000|pp=1–3}}</ref> |

|||

Vulgar Latin began to diverge into [[Romance languages|distinct languages]] by the 9th century at the latest, when the earliest extant Romance writings begin to appear. They were, throughout this period, confined to everyday speech, as, subsequent to Late Latin, Medieval Latin was used for writing. |

|||

=== Medieval Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Medieval Latin}} |

|||

[[File:Calligraphy.malmesbury.bible.arp.jpg|thumb|200px|Latin [[Bible]] from 1407]] |

|||

[[Medieval Latin]] is the written Latin in use during that portion of the post-classical period when no corresponding Latin vernacular existed. The spoken language had developed into the various incipient Romance languages; however, in the educated and official world Latin continued without its natural spoken base. Moreover, this Latin spread into lands that had never spoken Latin, such as the Germanic and Slavic nations. It became useful for international communication between the member states of the [[Holy Roman Empire]] and its allies. |

|||

Without the institutions of the Roman empire that had supported its uniformity, medieval Latin lost its linguistic cohesion: for example, in classical Latin ''sum'' and ''eram'' are used as auxiliary verbs in the perfect and pluperfect passive, which are compound tenses. Medieval Latin might use ''fui'' and ''fueram'' instead.<ref name=thorley13-15>{{cite book|pages=13–15|title=Documents in medieval Latin|first=Moe|last=Elabani|location=Ann Arbor|publisher=University of Michigan Press|year=1998|isbn=0-472-08567-0}}</ref> Furthermore the meanings of many words have been changed and new vocabularies have been introduced from the vernacular. Identifiable individual styles of classically incorrect Latin prevail.<ref name=thorley13-15/> |

|||

=== Renaissance Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Renaissance Latin}} |

|||

[[File:Incunabula distribution by language.png|thumb|Most 15th century printed books ([[incunabula]]) were in Latin, with the [[vernacular language]]s playing only a secondary role.<ref name="ISTC">{{cite web |url=http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/istc/index.html |title=Incunabula Short Title Catalogue |author= |work= |publisher=[[British Library]] |accessdate=2 March 2011}}</ref>]] |

|||

The [[Renaissance Latin|Renaissance]] briefly reinforced the position of Latin as a spoken language, through its adoption by the Renaissance [[Humanists]]. Often led by members of the clergy, they were shocked by the accelerated dismantling of the vestiges of the classical world and the rapid loss of its literature. They strove to preserve what they could. It was they who introduced the practice of producing revised editions of the literary works that remained by comparing surviving manuscripts, and they who attempted to restore Latin to what it had been. They corrected medieval Latin out of existence no later than the 15th century and replaced it with more formally correct versions supported by the scholars of the rising universities, who attempted, through scholarship, to discover what the classical language had been. |

|||

=== Early modern Latin === |

|||

{{main|New Latin}} |

|||

During the Early Modern Age, Latin still was the most important language of culture in Europe. Therefore, until the end of the 17th century the majority of books and almost all diplomatic documents were written in Latin. Afterwards, most diplomatic documents were written in [[French language|French]] and later just native or agreed-upon languages. |

|||

=== Modern Latin === |

|||

{{Main|Contemporary Latin}} |

|||

[[File:Wallsend platfom 2 02.jpg|thumb|left|The signs at [[Wallsend Metro station]] are in [[English language|English]] and Latin as a tribute to Wallsend's role as one of the outposts of the [[Roman Empire]].]] |

|||

The largest organization that retains Latin in official and quasi-official contexts is the [[Catholic Church]]. Latin remains the language of the [[Roman Rite]]; the [[Tridentine Mass]] is celebrated in Latin, and although the [[Mass of Paul VI]] is usually celebrated in the local [[vernacular language]], it can be and often is said in Latin, in part or whole, especially at multilingual gatherings. Latin is the official language of the [[Holy See]], the primary language of its [[public journal]], the ''[[Acta Apostolicae Sedis]]'', and the working language of the [[Roman Rota]]. The [[Vatican City]] is also home to the world's only [[Automatic Teller Machine|ATM]] that gives instructions in Latin.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Moore|first=Malcolm|title=Pope's Latinist pronounces death of a language|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1540843/Popes-Latinist-pronounces-death-of-a-language.html|journal=[[The Daily Telegraph]]|date=28 January 2007|accessdate=16 September 2009|ref=harv}}</ref> |

|||

In the [[Anglican Church]], after the publication of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer of 1559, a 1560 Latin edition was published for use at universities such as Oxford and the leading public schools, where the liturgy was still permitted to be conducted in Latin<ref>{{cite web|url=http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/Latin1560/BCP_Latin1560.htm |title=Liber Precum Publicarum, The Book of Common Prayer in Latin (1560). Society of Archbishop Justus, resources, Book of Common Prayer, Latin, 1560. Retrieved 22 May 2012 |publisher=Justus.anglican.org |accessdate=9 August 2012}}</ref> and there have been several Latin translations since. Most recently a Latin edition of the 1979 USA Anglican Book of Common Prayer has appeared.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/Latin1979/Latin_1979.htm |title=Society of Archbishop Justus, resources, Book of Common Prayer, Latin, 1979. Retrieved 22 May 2012 |publisher=Justus.anglican.org |accessdate=9 August 2012}}</ref> |

|||

Some films of ancient settings, such as ''[[Sebastiane]]'' and ''[[The Passion of the Christ]]'', have been made with dialogue in Latin for the sake of realism. Occasionally, Latin dialogue is used because of its association with religion or philosophy, in such film/[[television|TV]] series as ''[[The Exorcist (film)|The Exorcist]]'' and ''[[Lost (2004 TV series)|Lost]]'' ("[[Jughead (Lost)|Jughead]]"). Subtitles are usually shown for the benefit of those who do not understand Latin. There are also [[List of songs with Latin lyrics|songs written with Latin lyrics]]. The libretto for the opera-oratorio [[Oedipus rex (opera)|''Oedipus rex'' (opera)]] by [[Igor Stravinsky]] is in Latin. |

|||

[[Switzerland]] adopts the country's Latin short name "''Helvetia''" on coins and stamps, since there is no room to use all of the nation's four official languages. For a similar reason it adopted the international vehicle and internet code ''CH'', which stands for ''Confoederatio Helvetica'', the country's full Latin name. |

|||

[[File:Council of the EU logo.svg|thumb|right|The polyglot [[European Union]] has adopted Latin names in the logos of some of its institutions for the sake of linguistic compromise and as a sign of the continent's heritage (e.g. the [[Council of the European Union|EU Council]]: ''Consilium'')]] |

|||

Many organizations today have Latin mottos, such as "[[Semper Paratus|Semper paratus]]" (always ready), the motto of the [[United States Coast Guard]], and "[[Semper Fidelis|Semper fidelis]]" (always faithful), the motto of the [[United States Marine Corps]]. Several of the states of the United States also have Latin mottos, such as "[[Montani Semper Liberi|Montani semper liberi]]" (Mountaineers are always free), the state motto of [[West Virginia]]; "[[Sic semper tyrannis]]" (Thus always for tyrants), that of [[Virginia]]; "Qui transtulit sustinet" ("He who transplanted still sustains"), that of [[Connecticut]]; "[[Esse Quam Videri|Esse quam videri]]" (To be rather than to seem), that of [[North Carolina]]; "Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam, circumspice" ("If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you") that of [[Michigan]]. Another Latin motto is "[[Per ardua ad astra]]" (Through adversity/struggle to the stars), the motto of the [[Royal Air Force|RAF]]. Some schools adopt Latin mottos such as "[[Disce aut discede]]" of the [[Royal College, Colombo]]. [[Harvard University]]'s motto is "[[Veritas]]" meaning (truth). Veritas was the goddess of truth, a daughter of Saturn, and the mother of Virtue. |

|||

Similarly Canada's motto "A mari usque ad mare" (from sea to sea) and most provincial mottos are also in Latin (for example, British Columbia's is Splendor Sine Occasu (splendor without diminishment). |

|||

Occasionally, some media outlets broadcast in Latin, which is targeted at enthusiasts. Notable examples include [[Radio Bremen]] in [[Germany]], [[YLE]] radio in [[Finland]] and Vatican Radio & Television, all of which broadcast news segments and other material in Latin.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.radiobremen.de/nachrichten/latein/ |title=Latein: Nuntii Latini mensis lunii 2010: Lateinischer Monats rückblick |publisher=Radio Bremen |language=Latin |accessdate=16 July 2010}}<br>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6079852.stm|title=BBC NEWS | Europe | Finland makes Latin the King|last=Dymond|first=Jonny|date=24 October 2006|work=[[BBC Online]]|accessdate=29 January 2011}}<br>{{cite web |url=http://www.yle.fi/radio1/tiede/nuntii_latini/ |title=Nuntii Latini |publisher=YLE Radio 1 |language=Latin|accessdate=17 July 2010}}</ref> |

|||

There are many websites and forums maintained in Latin by enthusiasts. The [[Latin Wikipedia]] has more than 100,000 articles written in Latin. |

|||

Latin is taught in many high schools, especially in Europe and the Americas. It is most common in British [[Public school (United Kingdom)|Public School]]s and [[Grammar School]]s, the Italian [[Liceo classico]] and [[Liceo scientifico]], the German Humanistisches [[Gymnasium (Germany)|Gymnasium]], the Dutch [[Gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]], the [[Boston Latin School]] and Boston Latin Academy. In the [[Pontifical university|pontifical universities]] postgraduate courses of [[Canon law]] are taught in Latin and papers should be written in the same language. |

|||

== Phonology == |

|||

{{Main|Latin spelling and pronunciation}} |

|||

No inherited verbal knowledge of the ancient pronunciation of Latin exists. It must be reconstructed. Among the data used for reconstruction are explicit statements about pronunciation by ancient authors, misspellings, puns, ancient etymologies, and the spelling of Latin loanwords in other languages.<ref>{{harvnb|Allen|2004|pp=viii-ix}}</ref> |

|||

=== Consonants === |

|||

The consonant [[phoneme]]s of Classical Latin are shown in the following table.<ref>{{cite book|first=Andrew L.|last=Sihler|title=New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=IeHmqKY2BqoC|accessdate=12 March 2013|year=1995|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-508345-3}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable IPA" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan="2" rowspan="2" | |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Labial consonant|Labial]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Dental consonant|Dental]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Palatal consonant|Palatal]] |

|||

! colspan="2" | [[Velar consonant|Velar]] |

|||

! rowspan="2" | [[Glottal consonant|Glottal]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! plain |

|||

! [[Labialisation|labial]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan=2| [[Plosive consonant|Plosive]] |

|||

! <small>[[voice (phonetics)|voiced]]</small> |

|||

| b |

|||

| d |

|||

| |

|||

| ɡ |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>[[voicelessness|voiceless]]<small> |

|||

| p |

|||

| t |

|||

| |

|||

| k |

|||

| kʷ |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan=2| [[Fricative consonant|Fricative]] |

|||

! <small>[[voice (phonetics)|voiced]]<small> |

|||

| |

|||

| z |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! <small>[[voicelessness|voiceless]]<small> |

|||

| f |

|||

| s |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| h |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=2| [[Nasal consonant|Nasal]] |

|||

| m |

|||

| n |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=2| [[Rhotic consonant|Rhotic]] |

|||

| |

|||

| r |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

! colspan=2| [[Approximant consonant|Approximant]] |

|||

| |

|||

| l |

|||

| j |

|||

| |

|||

| w |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

During the time of [[Old Latin|Old]] and [[Classical Latin]], the Latin alphabet had no distinction between [[letter case|uppercase and lowercase]], and the letters {{angbr|J U W}} did not exist. In place of {{angbr|J U}}, the letters {{angbr|I V}} were used. {{angbr|I V}} represented both vowels and consonants. Most of the letterforms were similar to modern uppercase, as can be seen in the inscription from the Colosseum shown at the top of the article. |

|||

The spelling systems used in Latin dictionaries and modern editions of Latin texts, however, normally use {{angbr|i u}} in place of Classical-era {{angbr|I V}}. Some systems use {{angbr|j v}} for the consonant sounds {{IPA|/j w/}}, except in the combinations {{angbr|gu su qu}}, where {{angbr|v}} is never used. |

|||

Some notes concerning the mapping of Latin phonemes to English graphemes are given below. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ Notes |

|||

|- |

|||

! Latin<br>grapheme !! Latin<br>phone !! English examples |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|c}}, {{angbr|k}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[k]}} |

|||

| Always hard as ''k'' in ''sky'', never [[hard and soft C|soft]] as in ''Caesar'', ''cello'', or ''social'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|t}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[t]}} |

|||

| As ''t'' in ''stay'', never as ''t'' in ''nation'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|s}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[s]}} |

|||

| As ''s'' in ''say'', never as ''s'' in ''rise'' or ''issue'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|g}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ɡ]}} |

|||

| Always hard as ''g'' in ''good'', never [[hard and soft G|soft]] as ''g'' in ''gem'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[ŋ]}} |

|||

| Before {{angbr|n}}, as ''ng'' in ''sing'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|n}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[n]}} |

|||

| As ''n'' in ''man'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[ŋ]}} |

|||

| Before {{angbr|c}}, {{angbr|x}}, and {{angbr|g}}, as ''ng'' in ''sing'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|l}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[l]}} |

|||

| When doubled {{angbr|ll}} and before {{angbr|i}}, as clear ''l'' in ''link'' (''l exilis'')<ref>{{harvnb|Sihler|2008|p=174}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Allen|2004|pp=33–34}}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[ɫ]}} |

|||

| In all other positions, as dark ''l'' in ''bowl'' (''l pinguis'') |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|qu}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[kʷ]}} |

|||

| Similar to ''qu'' in ''quick'', never as ''qu'' in ''antique'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|u}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[w]}} |

|||

| Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, or after {{angbr|g}} and {{angbr|s}}, as ''w'' in ''wine'', never as ''v'' in ''vine'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|i}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[j]}} |

|||

| Sometimes at the beginning of a syllable, as ''y'' in ''yard'', never as ''j'' in ''just'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[jj]}} |

|||

| Doubled between vowels, as ''y y'' in ''toy yacht'' |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{angbr|x}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ks]}} |

|||

| A letter representing {{angbr|c}} + {{angbr|s}}: as ''x'' in English ''axe'', never as ''x'' in ''example'' |

|||

|} |

|||

[[Gemination|Doubled]] consonants in Latin are pronounced long. In English, consonants are only pronounced double between two words or [[morpheme]]s, as in ''unnamed'', which has a doubled {{IPA|/nn/}} like the ''nn'' in Latin ''annus''. |

|||

=== Vowels === |

|||

====Simple vowels==== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

|- |

|||

! !! Front !! Central !! Back |

|||

|- |

|||

! Close |

|||

| iː ɪ || || ʊ uː |

|||

|- |

|||

! Mid |

|||

| eː ɛ || || ɔ oː |

|||

|- |

|||

! Open |

|||

| || a aː || |

|||

|} |

|||

In the Classical period, the letter {{angbr|U}} was written as {{angbr|V}}, even when used as a vowel. {{angbr|Y}} was adopted to represent [[upsilon]] in loanwords from Greek, but it was pronounced like {{angbr|u}} and {{angbr|i}} by some speakers.<!--Also used in native Latin words by confusion with Greek words of similar meaning, such as sylva and ὕλη.--> |

|||

Classical Latin distinguished between [[vowel length|long and short vowels]]. During the Classical period, long vowels, except for {{angbr|I}}, were frequently marked using the [[apex (diacritic)|apex]], which was sometimes similar to an [[acute accent]] {{angbr|Á É Ó V́ Ý}}. Long {{IPA|/iː/}} was written using a taller version of {{angbr|I}}, called ''i longa'' "long I": {{angbr|ꟾ}}. In modern texts, long vowels are often indicated by a [[macron]] {{angbr|ā ē ī ō ū}}, and short vowels are usually unmarked, except when necessary to distinguish between words, in which case they are marked with a [[breve]]: {{angbr|ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ}}. |

|||

Long vowels in the Classical period were pronounced with a different quality from short vowels, as well as being longer. The difference is described in table below. |

|||

{| class=wikitable |

|||

|+ Pronunciation of Latin vowels |

|||

! Latin<br>grapheme |

|||

! Latin<br>phone |

|||

! modern examples |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|a}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[a]}} |

|||

| similar to ''u'' in ''cut'' when short |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[aː]}} |

|||

| similar to ''a'' in ''father'' when long |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|e}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ɛ]}} |

|||

| as ''e'' in ''pet'' when short |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[eː]}} |

|||

| similar to ''ey'' in ''they'' when long |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|i}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ɪ]}} |

|||

| as ''i'' in ''sit'' when short |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[iː]}} |

|||

| similar to ''i'' in ''machine'' when long |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|o}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ɔ]}} |

|||

| as ''o'' in ''sort'' when short |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[oː]}} |

|||

| similar to ''o'' in ''holy'' when long |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|u}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ʊ]}} |

|||

| similar to ''u'' in ''put'' when short |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[uː]}} |

|||

| similar to ''u'' in ''true'' when long |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | {{angbr|y}} |

|||

! {{IPA|[ʏ]}} |

|||

| similar to ''ü'' in German ''Stück'' when short (or as short ''u'' or ''i'') |

|||

|- |

|||

! {{IPA|[yː]}} |

|||

| as in [[French language|French]] ''lune'' when long (or as long ''u'' or ''i'') |

|||

|} |

|||

A vowel and {{angbr|m}} at the end of a word, or a vowel and {{angbr|n}} before {{angbr|s}} or {{angbr|f}}, is long and [[nasal vowel|nasal]], as in ''monstrum'' {{IPA|/mõːstrũː/}}. |

|||

====Diphthongs==== |

|||

Classical Latin had several [[diphthong]]s. The two most common were {{angbr|ae au}}. {{angbr|oe}} was fairly rare, and {{angbr|ui eu ei ou}} were very rare, at least in native Latin words.<ref name="classical diphthongs">{{Harvnb|Allen|2004|pp=60–63}}</ref> |

|||

These sequences sometimes did not represent diphthongs. {{angbr|ae}} and {{angbr|oe}} also represented a sequence of two vowels in different syllables in ''aēnus'' {{IPA|[aˈeː.nʊs]}} "of bronze" and ''coēpit'' {{IPA|[kɔˈeː.pɪt]}} "began", and {{angbr|au ui eu ei ou}} represented sequences of two vowels, or of a vowel and one of the semivowels {{IPA|/j w/}}, in ''cauē'' {{IPA|[ˈka.weː]}} "beware!", ''cuius'' {{IPA|[ˈkʊj.jʊs]}} "whose", ''monuī'' {{IPA|[ˈmɔn.ʊ.iː]}} "I warned", ''soluī'' {{IPA|[ˈsɔɫ.wiː]}} "I released", ''dēlēuī'' {{IPA|[deːˈleː.wiː]}} "I destroyed", ''eius'' {{IPA|[ˈɛj.jʊs]}} "his", and ''nouus'' {{IPA|[ˈnɔ.wʊs]}} "new". |

|||

Old Latin had more diphthongs, but most of them changed into long vowels in Classical Latin. The Old Latin diphthong {{angbr|ai}} and the sequence {{angbr|āī}} became Classical {{angbr|ae}}. Old Latin {{angbr|oi}} and {{angbr|ou}} changed to Classical {{angbr|ū}}, except in a few words, where {{angbr|oi}} became Classical {{angbr|oe}}. These two developments sometimes occurred in different words from the same root: for instance, Classical ''poena'' "punishment" and ''pūnīre'' "to punish".<ref name="classical diphthongs" /> Early Old Latin {{angbr|ei}} usually changed to Classical {{angbr|ī}}.<ref>{{Harvnb|Allen|2004|pp=53–55}}</ref> |

|||

In Vulgar Latin and the Romance languages, {{angbr|ae au oe}} merged with {{angbr|e ō ē}}. A similar pronunciation also existed during the Classical Latin period among less educated speakers.<ref name="classical diphthongs" /> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align: center;" |

|||

|+ Diphthongs classified by beginning sound |

|||

! !! Front !! Back |

|||

|- |

|||

! Close |

|||

| || ui {{IPA|/ui̯/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Mid |

|||

| ei {{IPA|/ei̯/}}<br>eu{{IPA|/eu̯/}} || oe {{IPA|/oe̯/}}<br>ou {{IPA|/ou̯/}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Open |

|||

| colspan="2" | ae {{IPA|/ae̯/}}<br>au {{IPA|/au̯/}} |

|||

|} |

|||

== Orthography == |

|||

{{Main|Latin alphabet}} |

|||

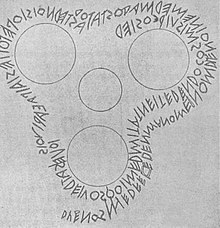

[[File:Duenos inscription.jpg|thumb|The [[Duenos Inscription]], from the 6th century BC, is one of the earliest known [[Old Latin]] texts.]] |

|||

Latin was written in the Latin alphabet, derived from the [[Old Italic alphabet]], which was in turn drawn from the [[Greek Alphabet|Greek]] and ultimately the [[Phoenician alphabet]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Diringer|1996|pp=451, 493, 530}}</ref> This alphabet has continued to be used over the centuries as the script for the Romance, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, Finnic, and many Slavic languages (Polish, Slovak, Slovene, Croatian and Czech), and has been adopted by many languages around the world, including [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]], the [[Austronesian languages]], many [[Turkic languages]], and most languages in [[sub-Saharan Africa]], the [[Americas]], and [[Oceania]], making it by far the world's single most widely used writing system. |

|||

The number of letters in the Latin alphabet has varied. When it was first derived from the Etruscan alphabet, it contained only 21.<ref>{{Harvnb|Diringer|1996|p=536}}</ref> Later, ''G'' was added to represent {{IPA|/ɡ/}}, which had previously been spelled ''C''; while ''Z'' ceased to be included in the alphabet due to non-use, as the language had no [[voiced alveolar fricative]] at the time.<ref name=D538>{{Harvnb|Diringer|1996|p=538}}</ref> The letters ''Y'' and ''Z'' were later added to represent the Greek letters [[upsilon]] and [[zeta]] respectively in Greek loanwords.<ref name=D538/> ''W'' was created in the 11th century from ''VV''. It represented {{IPA|/w/}} in Germanic languages, not in Latin, which still uses ''V'' for the purpose. ''J'' was distinguished from the original ''I'' only during the late Middle Ages, as was the letter ''U'' from ''V''.<ref name=D538/> Although some Latin dictionaries use ''J'', it is for the most part not used for Latin text as it was not used in classical times, although many other languages use it. |

|||

Classical Latin did not contain sentence [[punctuation]], letter case,<ref>{{Harvnb|Diringer|1996|p=540}}</ref> or [[interword spacing]], though [[apex (diacritic)|apices]] were sometimes used to distinguish length in vowels and the [[interpunct]] was used at times to separate words. So, the first line of Catullus 3, originally written as |

|||

: {{unicode|LV́GÉTEÓVENERÉSCVPꟾDINÉSQVE}} ("Mourn, O [[Venus (mythology)|Venuses]] and [[Cupid]]s") |

|||

or with interpunct as |

|||

: {{unicode|LV́GÉTE·Ó·VENERÉS·CVPꟾDINÉSQVE}} |

|||

* |

|||

would be rendered in a modern edition as |

|||

: Lugete, O Veneres Cupidinesque |

|||

or with macrons |

|||

: Lūgēte, Ō Venerēs Cupīdinēsque. |

|||

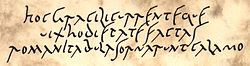

[[File:Hocgracili.jpg|thumb|250px|A replica of the Old Roman Cursive inspired by the [[Vindolanda tablets]]]] |

|||

The [[Roman cursive]] script is commonly found on the many [[wax tablet]]s excavated at sites such as forts, an especially extensive set having been discovered at Vindolanda on [[Hadrian's Wall]] in [[Great Britain|Britain]]. Curiously enough, most of the [[Vindolanda tablets]] show spaces between words, though spaces were avoided in monumental inscriptions from that era. |

|||

=== Alternate scripts === |

|||

Occasionally Latin has been written in other scripts: |

|||

* The disputed [[Praeneste fibula]] is a 7th-century BC pin with an Old Latin inscription written using the Etruscan script. |

|||

* The rear panel of the early eighth-century [[Franks Casket]] has an inscription that switches from [[Old English]] in [[Anglo-Saxon runes]] to Latin in Latin script and to Latin in runes. |

|||

== Grammar == |

|||

{{Main|Latin grammar}} |

|||

Latin is a [[Synthetic language|synthetic]], [[fusional language]], in the terminology of linguistic typology. In more traditional terminology, it is an inflected language, although the typologists are apt to say "inflecting". Thus words include an objective semantic element, and also markers specifying the grammatical use of the word. This fusion of root meaning and markers produces very compact sentence elements. For example, ''amō'', "I love," is produced from a semantic element, ''ama-'', "love," to which ''-ō'', a first person singular marker, is suffixed. |

|||

The grammatical function can be changed by changing the markers: the word is "inflected" to express different grammatical functions. The semantic element does not change. Inflection uses affixing and infixing. Affixing is prefixing and suffixing. Latin inflections are never prefixed. For example, ''amābit'', "he or she will love", is formed from the same stem, ''amā-'', to which a future tense marker, ''-bi-'', is suffixed, and a third person singular marker, ''-t'', is suffixed. There is an inherent ambiguity: ''-t'' may denote more than one grammatical category, in this case either masculine, feminine, or neuter gender. A major task in understanding Latin phrases and clauses is to clarify such ambiguities by an analysis of context. All natural languages contain ambiguities of one sort or another. |

|||

The inflections express [[grammatical gender|gender]], [[grammatical number|number]], and [[grammatical case|case]] in [[adjective]]s, [[noun]]s, and [[pronoun]]s—a process called ''[[declension]]''. Markers are also attached to fixed stems of verbs, to denote [[grammatical person|person]], number, [[grammatical tense|tense]], [[grammatical voice|voice]], [[grammatical mood|mood]], and [[grammatical aspect|aspect]]—a process called ''[[grammatical conjugation|conjugation]]''. Some words are uninflected, not undergoing either process, such as adverbs, prepositions, and interjections. |

|||

=== Nouns === |

|||

{{Main|Latin declension}} |

|||

A regular Latin noun belongs to one of five main declensions, a group of nouns with similar inflected forms. The declensions are identified by the genitive singular form of the noun. The first declension, with a predominant ending letter of a, is signified by the genitive singular ending of ''-ae''. The second declension, with a predominant ending letter of o, is signified by the genitive singular ending of ''-i''. The third declension, with a predominant ending letter of i, is signified by the genitive singular ending of ''-is''. The fourth declension, with a predominant ending letter of u, is signified by the genitive singular ending of ''-ūs''. And the fifth declension, with a predominant ending letter of e, is signified by the genitive singular ending of ''-ei''. |

|||

There are seven Latin noun cases, which also apply to adjectives and pronouns. These mark a noun's syntactic role in the sentence by means of inflections, so [[word order]] is not as important in Latin as it is in other less inflected languages, such as English. The general structure and word order of a Latin sentence can therefore vary. The cases are as follows: |

|||

# '''[[Nominative case|Nominative]]''' – used when the noun is the [[Subject (grammar)|subject]] or a [[predicate nominative]]. The thing or person acting; e.g., the '''girl''' ran: '''''puella''' cucurrit,'' or ''cucurrit '''puella''''' |

|||

# '''[[Genitive case|Genitive]]''' – used when the noun is the possessor of or connected with an object (e.g., "the horse of the man", or "the man's horse"—in both of these instances, the word ''man'' would be in the [[genitive case]] when translated into Latin). Also indicates the [[partitive]], in which the material is quantified (e.g., "a group of people"; "a number of gifts"—''people'' and ''gifts'' would be in the genitive case). Some nouns are genitive with special verbs and adjectives too (e.g., The cup is full of '''wine'''. ''Poculum plēnum '''vīnī''' est.'' The master of the '''slave''' had beaten him. ''Dominus '''servī''' eum verberāverat.'') |

|||

# '''[[Dative case|Dative]]'''-- used when the noun is the indirect object of the sentence, with special verbs, with certain prepositions, and if used as agent, reference, or even possessor. (e.g., The merchant hands the [[stola]] '''to the woman'''. ''Mercātor '''fēminae''' stolam trādit.'') |

|||

# '''[[Accusative case|Accusative]]''' – used when the noun is the direct object of the subject, and as object of a preposition demonstrating place to which. (e.g., The man killed '''the boy'''. ''Homō necāvit '''puerum'''.'') |

|||

# '''[[Ablative case|Ablative]]''' – used when the noun demonstrates separation or movement from a source, cause, [[agent (grammar)|agent]], or [[instrumental case|instrument]], or when the noun is used as the object of certain prepositions; adverbial. (e.g., You walked '''with the boy'''. ''cum '''puerō''' ambulāvistī.'') |

|||

# '''[[Vocative case|Vocative]]''' – used when the noun is used in a direct address. The vocative form of a noun is the same as the nominative except for second-declension nouns ending in ''-us''. The ''-us'' becomes an ''-e'' in the vocative singular. If it ends in ''-ius'' (such as ''fīlius'') then the ending is just ''-ī'' (''filī'') (as distinct from the nominative plural (''filiī'')) in the vocative singular. (e.g., "'''Master'''!" shouted the slave. ''"'''Domine'''!" clāmāvit servus.'') |

|||

# '''[[Locative case|Locative]]''' – used to indicate a location (corresponding to the English "in" or "at"). This is far less common than the other six cases of Latin nouns and usually applies to cities, small towns, and islands smaller than the island of [[Rhodes]], along with a few common nouns, such as the word ''domus'', house. In the first and second declension singular, its form coincides with the genitive (''Roma'' becomes ''Romae'', "in Rome"). In the plural, and in the other declensions, it coincides with the ablative (''Athēnae'' becomes ''Athēnīs'', "at Athens"). In the case of the fourth declension word ''domus'', the locative form, ''domī'' ("at home") differs from the standard form of all the other cases. |

|||

Latin lacks both definite and indefinite [[article (grammar)|articles]]; thus ''puer currit'' can mean either "the boy is running" or "a boy is running". |

|||

===Adjectives=== |

|||

{{Main|Latin declension}} |

|||

There are two types of regular Latin adjectives: first and second declension and third declension, so called because their forms are similar, if not identical to, first and second declension and third declension nouns, respectively. Latin adjectives also have comparative (more --, ''-er'') and superlative (most --, ''est'') forms. There are also a number of Latin participles. |

|||

Latin numbers are sometimes declined, but more often than not aren't. See ''Numbers'' below. |

|||

====First and second declension adjectives==== |

|||

First and second declension adjectives are declined like first declension nouns for the feminine forms and like second declension nouns for the masculine and neuter forms. For example, for ''mortuus, mortua, mortuum''(dead)', ''mortua'' is declined like a regular first declension noun (such as ''puella'' (girl)), ''mortuus'' is declined like a regular second declension masculine noun (such as ''dominus'' (lord, master)), and ''mortuum'' is declined like a regular second declension neuter noun ( such as ''auxilium'' (help)). |

|||

'''<small>First and second declension ''-er'' adjectives</small>''' |

|||

Some first and second declension adjectives have an ''-er'' as the masculine nominative singular form. These are declined like regular first and second declension adjectives. Some adjectives keep the ''e'' for all of the forms while some adjectives do not. |

|||

====Third declension adjectives==== |

|||

Third declension adjectives are mostly declined like normal third declension nouns, with a few exceptions. In the plural nominative neuter, for example, the stem is ''-ia'' (ex. ''omnia''(all, everything)); while for third declension nouns, the plural nominative neuter ending is ''-a'' (ex. ''capita'' (head)) They can either have one, two, or three forms for the masculine, feminine, and neuter nominative singular. |

|||

====Participles==== |

|||

Latin participles, like English participles, are formed from a verb. There are a few main types of participles, including: |

|||

===Prepositions=== |

|||

Latin sometimes uses prepositions, and sometimes does not, depending on the type of prepositional phrase being used. Prepositions can take two cases for their object: the accusative (ex. "apud puerum" (with the boy), with "puerum" being the accusative form of "puer", boy) and the ablative (ex. "sine puero" (without the boy), with "puero" being the ablative form of "puer", boy). |

|||

=== Verbs === |

|||

{{Main|Latin conjugation}} |

|||

A regular verb in Latin belongs to one of four main [[Latin conjugation|conjugations]]. A conjugation is "a class of verbs with similar inflected forms."<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | title=Conjugation | encyclopedia=Webster's II new college dictionary | location=Boston | publisher=Houghton Mifflin | year=1999}}</ref> The conjugations are identified by the last letter of the verb's present stem. The present stem can be found by taking the -re (or -ri, in the case of a deponent verb) ending off of the present infinitive. The infinitive of the first conjugation ends in ''-ā-re'' or ''-ā-ri'' (active and passive respectively); e.g., ''amāre'', "to love," ''hortārī'', "to exhort"; of the second conjugation by ''-ē-re'' or ''-ē-rī''; e.g., ''monēre'', "to warn", ''verērī'', "to fear;" of the third conjugation by ''-ere'', ''-ī''; e.g., ''dūcere'', "to lead," ''ūtī'', "to use"; of the fourth by ''-ī-re'', ''-ī-rī''; e.g., ''audīre'', "to hear," ''experīrī'', "to attempt". Irregular verbs may not follow these types, or may be marked in a different way. The "endings" presented above are not the suffixed infinitive markers. The first letter in each case is the last of the stem, because of which the conjugations are also called the a-conjugation, e-conjugation and i-conjugation. The fused infinitive ending is -re or -rī. Third-conjugation stems end in a consonant: the consonant conjugation. Further, there is a subset of the 3rd conjugation, the i-stems, which behave somewhat like the 4th conjugation, as they are both i-stems, one short and the other long.<ref>{{cite book|title=Wheelock's Latin|last=Wheelock|first=Frederic M.|publisher=CollinsReference|edition=7th|location=New York|date=2011}}</ref> These stem categories descend from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Indo-European]], and can therefore be compared to similar conjugations in other Indo-European languages. |

|||

There are six general [[grammatical tense|tenses]] in Latin (present, imperfect, future, perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect), three [[grammatical mood|moods]] (indicative, imperative and subjunctive, in addition to the [[infinitive]], [[participle]], [[gerund]], [[gerundive]] and [[supine]]), three [[grammatical person|persons]] (first, second, and third), two numbers (singular and plural), two [[grammatical voice|voices]] (active and passive), and three [[grammatical aspect|aspects]] ([[Perfective and imperfective|perfective, imperfective]], and [[Stative verb|stative]]). Verbs are described by four principal parts: |

|||

# The first principal part is the first person singular, present tense, indicative mood, active voice form of the verb. If the verb is impersonal, the first principal part will be in the third person singular. |

|||

# The second principal part is the present infinitive active. |

|||

# The third principal part is the first person singular, perfect indicative active form. Like the first principal part, if the verb is impersonal, the third principal part will be in the third person singular. |

|||

# The fourth principal part is the supine form, or alternatively, the nominative singular, perfect passive participle form of the verb. The fourth principal part can show either one gender of the participle, or all three genders (''-us ''for masculine, ''-a'' for feminine, and ''-um'' for neuter), in the nominative singular. The fourth principal part will be the future participle if the verb cannot be made passive. Most modern Latin dictionaries, if only showing one gender, tend to show the masculine; however, many older dictionaries will instead show the neuter, as this coincides with the supine. The fourth principal part is sometimes omitted for intransitive verbs, although strictly in Latin these can be made passive if used impersonally, and the supine exists for these verbs. |

|||

There are six tenses in the Latin language. These are divided into two tense systems: the present system, which is made up of the present, imperfect, and future tenses, and the perfect system, which is made up of the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. Each tense has a set of endings corresponding to the person and number referred to. This means that subject (nominative) pronouns are generally unnecessary for the first (''I, we'') and second (''you'') persons, unless emphasis on the subject is needed. |

|||

The table below displays the common inflected endings for the indicative mood in the active voice in all six tenses. For the future tense, the first listed endings are for the first and second conjugations, while the second listed endings are for the third and fourth conjugations. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|||

! Tense !! 1st Person Singular !! 2nd Person Singular !! 3rd Person Singular !! 1st Person Plural !! 2nd Person Plural !! 3rd Person Plural |

|||

|- |

|||

| Present || -ō/m || -s || -t || -mus || -tis || -nt |

|||

|- |

|||

| Future || -bō, -am || -bis, -ēs || -bit, -et || -bimus, -ēmus || -bitis, -ētis |

|||

| -bunt, -ent |

|||

|- |

|||

| Imperfect || -bam || -bās || -bat || -bāmus || -bātis || -bant |

|||

|- |

|||

| Perfect || -ī || -istī || -it || -imus || -istis || -ērunt |

|||

|- |

|||

| Future Perfect || -erō || -eris || -erit || -erimus || -eritis || -erint |

|||

|- |

|||

| Pluperfect || -eram || -erās || -erat || -erāmus || -erātis || -erant |

|||

|} |

|||

Note that the future perfect endings are identical to the future forms of ''sum'' (with the exception of ''erint'') and that the pluperfect endings are identical to the imperfect forms of ''sum''. |

|||

==== Deponent verbs ==== |

|||

A number of Latin words are [[Deponent verb|deponent]], causing their forms to be in the passive mood, while retaining an active meaning, e.g. ''hortor, hortārī, hortātus sum (to urge). |

|||

== Vocabulary == |

|||

As Latin is an Italic language, most of its vocabulary is likewise Italic, deriving ultimately from [[PIE]]. However, because of close cultural interaction, the Romans not only adapted the Etruscan alphabet to form the Latin alphabet, but also borrowed some [[Etruscan language|Etruscan]] words into their language, including ''persona'' (mask) and ''histrio'' (actor).<ref name=H&S13>{{harvnb|Holmes|Schultz|1938|p=13}}</ref> Latin also included vocabulary borrowed from [[Oscan language|Oscan]], another Italic language. |

|||

After the [[History of Taranto|Fall of Tarentum]] (272 BC), the Romans began hellenizing, or adopting features of Greek culture, including the borrowing of Greek words, such as ''camera'' (vaulted roof), ''sumbolum'' (symbol), and ''balineum'' (bath).<ref name=H&S13/> This hellenization led to the addition of "Y" and "Z" to the alphabet to represent Greek sounds.<ref>{{cite book |first=David |last=Sacks |year=2003 |title=Language Visible: Unraveling the Mystery of the Alphabet from A to Z |location=London |publisher=Broadway Books |page=351 |isbn=0-7679-1172-5}}</ref> Subsequently the Romans transplanted [[Greek art]], [[medicine]], [[science]] and [[philosophy]] to Italy, paying almost any price to entice Greek skilled and educated persons to Rome, and sending their youth to be educated in Greece. Thus, many Latin scientific and philosophical words were Greek loanwords or had their meanings expanded by association with Greek words, as ''ars'' (craft) and τέχνη.<ref name=H&S14>{{harvnb|Holmes|Schultz|1938|p=14}}</ref> |

|||

Because of the Roman Empire’s expansion and subsequent trade with outlying European tribes, the Romans borrowed some northern and central European words, such as ''beber'' (beaver), of Germanic origin, and ''bracae'' (breeches), of Celtic origin.<ref name=H&S14/> The specific dialects of Latin across Latin-speaking regions of the former Roman Empire after its fall were influenced by languages specific to the regions. These spoken Latins evolved into particular Romance languages. |

|||

During and after the adoption of Christianity into Roman society, Christian vocabulary became a part of the language, formed either from Greek or Hebrew borrowings, or as Latin neologisms.<ref>{{Cite journal |url=http://homepages.wmich.edu/~johnsorh/MedievalLatin/Norberg/NORBINTR.html |contribution=Latin at the End of the Imperial Age |first=Dag |last=Norberg |title=Manuel pratique de latin médiéval |origyear=1980 |first2=Rand H, Translator | last2=Johnson |year=2004 |publisher=University of Michigan|accessdate=14 July 2010 |ref=harv |postscript=<!-- None -->}}</ref> Continuing into the Middle Ages, Latin incorporated many more words from surrounding languages, including [[Old English]] and other [[Germanic languages]]. |

|||

Over the ages, Latin-speaking populations produced new adjectives, nouns, and verbs by [[affix]]ing or [[Compound (linguistics)|compounding]] meaningful [[Segment (linguistics)|segment]]s.<ref>{{harvnb|Jenks|1911|pp=3, 46}}</ref> For example, the compound adjective, ''omnipotens'', "all-powerful," was produced from the adjectives ''omnis'', "all", and ''potens'', "powerful", by dropping the final ''s'' of ''omnis'' and concatenating. Often the concatenation changed the part of speech; i.e., nouns were produced from verb segments or verbs from nouns and adjectives.<ref>{{harvnb|Jenks|1911|pp=35, 40}}</ref> |

|||

== Phrases == |

|||

Here the phrases are mentioned with [[Pitch accent|accents]] to know where to stress.<ref>Ebbe Vilborg - ''Norstedts svensk-latinska ordbok'' - Second edition, 2009.</ref> In the Latin language, most of the Latin words are stressed at the second to last (penultimate) [[syllable]], called in Latin ''paenultimus'' or ''syllaba paenultima''.<ref name=LKHS>[[Tore Janson]] - ''Latin - Kulturen, historien, språket'' - First edition, 2009.</ref> Lesser words are stressed at the third to last syllable, called in Latin ''antepaenultimus'' or ''syllaba antepaenultima''.<ref name=LKHS/> |

|||

'''sálve''' <small>to one person</small> / '''salvéte''' <small>to more than one person</small> - hello |

|||

'''áve''' <small>to one person</small> / '''avéte''' <small>to more than one person</small> - greetings |

|||

'''vále''' <small>to one person</small> / '''valéte''' <small>to more than one person</small> - goodbye |

|||

'''cúra ut váleas''' - take care |

|||

'''exoptátus''' <small>to male</small> / '''exoptáta''' <small>to female</small>, '''optátus''' <small>to male</small> / '''optáta''' <small>to female</small>, '''grátus''' <small>to male</small> / '''gráta''' <small>to female</small>, '''accéptus''' <small>to male</small> / '''accépta''' <small>to female</small> - welcome |

|||

'''quómodo váles?''', '''ut váles?''' - how are you? |

|||

'''béne''' - good |

|||

'''amabo te''' - please |

|||

'''béne váleo''' - I'm fine |

|||

'''mále''' - bad |

|||

'''mále váleo''' - I'm not good |

|||

'''quáeso''' (['kwajso]/['kwe:so]) - please |

|||

'''íta''', '''íta est''', '''íta véro''', '''sic''', '''sic est''', '''étiam''' - yes |

|||

'''non''', '''minime''' - no |

|||

'''grátias tíbi''', '''grátias tíbi ágo''' - thank you |

|||

'''mágnas grátias''', '''mágnas grátias ágo''' - many thanks |

|||

'''máximas grátias''', '''máximas grátias ágo''', '''ingéntes grátias ágo''' - thank you very much |

|||

'''accípe sis''' <small>to one person</small> / '''accípite sítis''' <small>to more than one person</small>, '''libénter''' - you're welcome |

|||

'''qua aetáte es?''' - how old are you? |

|||

'''25 ánnos nátus''' <small>to male</small> / 25 ánnos náta <small>to female</small> - 25 years old |

|||

'''loquerísne ...''' - do you speak ... |

|||

*'''Latíne?''' - Latin? |

|||

*'''Gráece?''' (['grajke]/['gre:ke]) - Greek? |

|||

*'''Ánglice?''' (['aŋlike]) - English? |

|||

*'''Italiáne?''' - Italian? |

|||

*'''Gallice?''' - French? |

|||

*'''Hispánice?''' - Spanish? |

|||

*'''Lusitánice?''' - Portuguese? |

|||

*'''Theodísce?''' ([teo'diske]) - German? |

|||

*'''Sínice?''' - Chinese? |

|||

*'''Iapónice?''' ([ja'po:nike]) - Japanese? |

|||

*'''Coreane?''' - Korean? |

|||

*'''Tagale?''' - Tagalog? |

|||

*'''Arábice?''' - Arabic? |

|||

*'''Pérsice?''' - Persian? |

|||

*'''Indice?''' - Hindi? |

|||

*'''Rússice?''' - Russian? |

|||

'''úbi latrína est?''' - where is the toilet? |

|||

'''ámo te''' / '''te ámo''' - I love you |

|||

== Numbers == |

|||

In ancient times, numbers in Latin were only written with letters. Today, the numbers can be written with the [[Arabic numerals|Arabic numbers]] as well as with [[Roman numerals]]. The numbers 1, 2 and 3, and from 200 to 900, are declined as nouns and adjectives with some differences. |

|||

{| |

|||

|- |

|||

|''ūnus, ūna, ūnum'' (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

|||

| |

|||

|I |

|||

| |

|||

|one |

|||

|- |

|||

|''duo, duae, duo'' (m., f., n.) |

|||

| |

|||

|II |

|||

| |

|||

|two |

|||

|- |

|||

|''trēs, tria'' (m./f., n.) |

|||

| |

|||

|III |

|||

| |

|||

|three |

|||

|- |

|||

|''quattuor'' |

|||

| |

|||

|IIII <small>or</small> IV |

|||

| |

|||

|four |

|||

|- |

|||

|''quīnque'' |

|||

| |

|||

|V |

|||

| |

|||

|five |

|||

|- |

|||

|''sex'' |

|||

| |

|||

|VI |

|||

| |

|||

|six |

|||

|- |

|||

|''septem'' |

|||

| |

|||

|VII |

|||

| |

|||

|seven |

|||

|- |

|||

|''octō'' |

|||

| |

|||

|VIII |

|||

| |

|||

|eight |

|||

|- |

|||

|''novem'' |

|||

| |

|||

|VIIII <small>or</small> IX |

|||

| |

|||

|nine |

|||

|- |

|||

|''decem'' |

|||

| |

|||

|X |

|||

| |

|||

|ten |

|||

|- |

|||

| ''quīnquāgintā'' |

|||

| |

|||

|L |

|||

| |

|||

|Fifty (50) |

|||

|- |

|||

|Centum |

|||

| |

|||

|C |

|||

| |

|||

|One Hundred (100) |

|||

|- |

|||

|Quīngentī |

|||

| |

|||

|D |

|||

| |

|||

|Five Hundred (500) |

|||

|- |

|||

|Mīlle |

|||

| |

|||

|M |

|||

| |

|||

|One Thousand (1000) |

|||

|} |

|||

The numbers from quattuor (four) to centum (one hundred) do not change their endings. |

|||

== Example text == |

|||

''[[Commentarii de Bello Gallico]]'', also called ''De Bello Gallico'' (''The Gallic War''), written by [[Julius Caesar|Gaius Julius Caesar]], begins with the following passage: |

|||

{{quote|Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur. Hi omnes lingua, institutis, legibus inter se differunt. Gallos ab Aquitanis Garumna flumen, a Belgis Matrona et Sequana dividit. Horum omnium fortissimi sunt Belgae, propterea quod a cultu atque humanitate provinciae longissime absunt, minimeque ad eos mercatores saepe commeant atque ea quae ad effeminandos animos pertinent important, proximique sunt Germanis, qui trans Rhenum incolunt, quibuscum continenter bellum gerunt. Qua de causa Helvetii quoque reliquos Gallos virtute praecedunt, quod fere cotidianis proeliis cum Germanis contendunt, cum aut suis finibus eos prohibent aut ipsi in eorum finibus bellum gerunt. Eorum una pars, quam Gallos obtinere dictum est, initium capit a flumine Rhodano, continetur Garumna flumine, Oceano, finibus Belgarum; attingit etiam ab Sequanis et Helvetiis flumen Rhenum; vergit ad septentriones. Belgae ab extremis Galliae finibus oriuntur; pertinent ad inferiorem partem fluminis Rheni; spectant in septentrionem et orientem solem. Aquitania a Garumna flumine ad Pyrenaeos montes et eam partem Oceani quae est ad Hispaniam pertinet; spectat inter occasum solis et septentriones.}} |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{multicol}} |

|||

* [[Classical compound]] |

|||

* [[Greek and Latin roots in English]] |

|||

* [[Hybrid word]] |

|||

* [[Latin mnemonics]] |

|||

* [[Latin school]] |

|||

* [[List of Latin phrases]] |

|||

* [[Lorem ipsum]] |

|||

* [[Romanization (cultural)]] |

|||

* [[Toponymy]] |

|||

* [[Wikipedia:IPA for Latin]] |

|||

{{multicol-break}} |

|||

* [[:la:Pagina prima|Latin Wikipedia]] |

|||

* [[Gregorian chant]] |

|||

{{Portal|Ancient Rome|Language|Catholicism}} |

|||

{{multicol-break}} |

|||

'''Lists:''' |

|||

* [[List of Greek words with English derivatives]] |

|||

* [[List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names]] |

|||

* [[List of Latin abbreviations]] |

|||

* [[List of Latin phrases]] |

|||

* [[List of Latin words with English derivatives]] |

|||

* [[List of Latinised names]] |

|||

{{multicol-end}} |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{columns-list|30em| |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | last=Allen |first=William Sidney |year=2004 |title=Vox Latina – a Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin |edition=2nd |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=0-521-22049-1}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | title=The foundations of Latin | first=Philip | last=Baldi | location=Berlin | publisher=Mouton de Gruyter | year=2002}} |

|||

* {{cite book| ref=harv | last=Bennett|first=Charles E.|title=Latin Grammar|publisher=Allyn and Bacon|location=Chicago|year=1908 |isbn=1-176-19706-1}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | title=A grammar of Oscan and Umbrian, with a collection of inscriptions and a glossary | first=Carl Darling | last=Buck | location=Boston | publisher=Ginn & Company | year=1904}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | first=Victor Selden |last=Clark |year=1900 |title=Studies in the Latin of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance |location=Lancaster |publisher=The New Era Printing Company}} |

|||

* {{cite book| ref=harv | last=Diringer|first=David|title=The Alphabet – A Key to the History of Mankind|publisher=Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Private Ltd.|location=New Delhi|year=1996|origyear=1947|isbn=81-215-0748-0}} |

|||

* {{cite book| ref=harv | title=Vulgar Latin|first1=József |last1=Herman|first2=Roger (Translator) |last2=Wright|location=University Park, PA|publisher=[[Pennsylvania State University Press]]|year=2000 |isbn=0-271-02000-8}} |

|||

* {{cite book| ref=harv |last1=Holmes|first1=Urban Tigner|last2=Schultz|first2=Alexander Herman|title=A History of the French Language|location=New York|publisher=Biblo-Moser|isbn=0-8196-0191-8|year=1938}} |

|||

* {{cite book | ref=harv | last=[[Tore Janson|Janson, Tore]] |year=2004 |title=A Natural History of Latin |location=Oxford |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |isbn= 0-19-926309-4}} |

|||