Green tea: Difference between revisions

| Line 252: | Line 252: | ||

* [http://www.lipton.com/en_en/pdf/green_tea_catechins_and_body_shape.pdf Green Tea and Body Shape (overview from the Lipton Institute of Tea)] |

* [http://www.lipton.com/en_en/pdf/green_tea_catechins_and_body_shape.pdf Green Tea and Body Shape (overview from the Lipton Institute of Tea)] |

||

* [http://www.scientistlive.com/European-Food-Scientist/Q&A/SLAM%3A_Green_Tea%27s_cancer_fighting_potential/22907/ Green Tea's cancer fighting potential (Audio interview)] |

* [http://www.scientistlive.com/European-Food-Scientist/Q&A/SLAM%3A_Green_Tea%27s_cancer_fighting_potential/22907/ Green Tea's cancer fighting potential (Audio interview)] |

||

* [http://healthmad.com/alternative/10-great-benefits-of-drinking-green-tea/ 10 great benefits of drinking green tea] |

|||

{{Teas}} |

{{Teas}} |

||

Revision as of 08:29, 12 October 2009

Template:ChineseText Template:JapaneseText

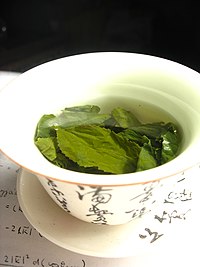

Green tea is a type of tea made solely with the leaves of Camellia sinensis that has undergone minimal oxidation during processing. Green tea originates from China and has become associated with many cultures in Asia from Japan to the Middle East. Recently, it has become more widespread in the West, where black tea is traditionally consumed. Many varieties of green tea have been created in countries where it is grown. These varieties can differ substantially due to variable growing conditions, processing and harvesting time.

Over the last few decades green tea has been subjected to many scientific and medical studies to determine the extent of its long-purported health benefits, with some evidence suggesting regular green tea drinkers may have lower chances of heart disease and developing certain types of cancer.[1] Green tea has also been claimed as useful for "weight loss management" [citation needed] - a claim with no scientific support according to medical databases such as PubMed.

Chinese tea

Hunan Province

Junshan Yinzhen (Silver Needle tea), known as one of the ten most famous Chinese Teas, is one variety of White Tea. It is also known as a silver needle tea as is Bai Hao Yinzhen tea. It is cultivated on Junshan Island, Yueyang City, Hunan Provice.

Zhejiang Province

Zhejiang is home to the most famous of all teas, Xi Hu Longjing, as well as many other high-quality green teas.

- 龙井 Longjing

- The most well-known of famous Chinese teas from Hangzhou, whose name in Chinese means dragon well. It is pan-fired and has a distinctive flat appearance. Falsification of Longjing is very common, and most of the tea on the market is in fact produced in Sichuan Province[citation needed] and hence not authentic Longjing.

- Named after a temple in Zhejiang.

- A tea from Kaihua County known as Dragon Mountain.

- A tea from Tiantai County and named after a peak in the Tiantai mountain range.

- A tea from Tian Mu, also known as Green Top.

Jiangsu Province

- 碧螺春 Bi Luo Chun

- A Chinese famous tea also known as Green Snail Spring, from Dong Ting. As with Longjing, falsification is common and most of the tea marketed under this name may, in fact, be grown in Sichuan.

- A tea from Nanjing.

Fujian Province

- The Fujian Province is known for mountain-grown organic green tea as well as white and oolong teas. The coastal mountains provide a perfect growing environment for tea growing. Green tea is picked in spring and summer seasons.

- Famous tea varieties from this south-eastern region of mainland China include Mao Feng ("fur tip"), Cui Jian ("jade sword") and Mo Li Hua Cha ("dragon pearl") green teas as well as Bai Mu Dan (white peony) white tea and Ti Kwan Yin ("iron goddess") oolong tea. Green tea is heat-cured using ovens or dings; white tea is fast-dried; oolong tea is oxidized through carefully-controlled fermentation.

Hubei Province

- A steamed tea known as Gyokuro (Jade Dew) made in the Japanese style.

Henan Province

- 信阳毛尖 Xin Yang Mao Jian

- A Chinese famous tea also known as Green Tip, or Tippy Green.

Jiangxi Province

- A well-known tea within China and recipient of numerous national awards.

- A tea also known as Cloud and Mist.

Anhui Province

Anhui Province is home to several varieties of tea, including three Chinese famous teas. These are:

- 大方 Da Fang

- A tea from Mount Huangshan also known as Big Square suneet.

- 黄山毛峰 Huangshan Maofeng

- A Chinese famous tea from Mount Huang.

- 六安瓜片 Lu'An Guapian

- A Chinese famous tea also known as Melon Seed.

- 猴魁 Hou Kui

- A Chinese famous tea also known as Monkey tea.

- 屯绿 Tun Lu

- A tea from Tunxi District.

- 火青 Huo Qing

- A tea from Jing County, also known as Fire Green.

- A medium-quality tea from many provinces, an early-harvested tea.

Japanese green teas

Green tea (緑茶, Ryokucha) is ubiquitous in Japan and therefore is more commonly known simply as "tea" (お茶, ocha). It is even referred to as "Japanese tea" (日本茶, nihoncha) though it was first used in China during the Song Dynasty, and brought to Japan by Myōan Eisai, a Japanese Buddhist priest who also introduced the Rinzai school of Zen Buddhism. Types of tea are commonly graded depending on the quality and the parts of the plant used as well as how they are processed. There are large variations in both price and quality within these broad categories, and there are many specialty green teas that fall outside this spectrum. The best Japanese green tea is said to be that from the Yame region of Fukuoka Prefecture and the Uji region of Kyoto. Shizuoka Prefecture produces 40% of raw tea leaf.

- Bancha (番茶, coarse tea)

- Lower grade of Sencha harvested as a third or fourth flush tea between summer and autumn. Aki-Bancha (autumn Bancha) is not made from entire leaves, but from the trimmed unnecessary twigs of the tea plant.

- Genmaicha (玄米茶, brown rice tea)

- Bancha (sometimes Sencha) and roasted genmai (brown rice) blend. It is often mixed with a small amount of Matcha to make the color better.

- Gyokuro (玉露, Jade Dew)

- The highest grade Japanese green tea cultivated in special way. Gyokuro's name refers to the pale green color of the infusion. The leaves are grown in the shade before harvest, which alters their flavor.

- Hōjicha (焙じ茶, roasted tea)

- A green tea roasted over charcoal.

- Kabusecha (冠茶, covered tea)

- Kabusecha is sencha, the leaves of which have grown in the shade prior to harvest, although not for as long as Gyokuro. It has a more delicate flavor than Sencha.

- Kamairicha tea (窯煎茶, pan-fried tea)

- Kamairicha is a pan-fried green tea that does not undergo the usual steam treatments of Japanese tea and does not have the characteristic bitter taste of most Japanese tea.

- Kukicha (茎茶, stalk tea)

- A tea made from stems, stalks, and twigs. Kukicha has a mildly nutty, and slightly creamy sweet flavor.

- Matcha (抹茶, powdered tea)

- A fine ground tea made from tencha (碾茶). It has a very similar cultivation process as Gyokuro. It is used primarily in the tea ceremony. Matcha is also a popular flavor of ice cream and other sweets in Japan.

- Mecha (芽茶, buds and tips tea)

- Mecha is green tea derived from a collection of leaf buds and tips of the early crops. Mecha is harvested in spring and made as rolled leaf teas that are graded somewhere between Gyokuro and Sencha in quality.

- Sencha (煎茶, broiled tea)

- The first and second flush of green tea, which is the most common green tea in Japan made from leaves that are exposed directly to sunlight. The first flush is also called shincha (新茶, a new tea) and specially long steamed leaves mushicha (蒸し茶).

- Tamaryokucha (玉緑茶, lit. ball green tea)

- Tamaryokucha has a tangy, berry-like taste, with a long almondy aftertaste and a deep aroma with tones of citrus, grass, and berries.

Other green teas

Brewing

Generally, 2 grams of tea per 100ml of water, or about one teaspoon of green tea per 5 ounce cup, should be used. With very high quality teas like gyokuro, more than this amount of leaf is used, and the leaf is steeped multiple times for short durations.

Green tea brewing time and temperature varies with individual teas. The hottest brewing temperatures are 180°F to 190°F (81°C to 87°C) water and the longest steeping times 2 to 3 minutes. The coolest brewing temperatures are 140°F to 160°F (61°C to 69°C) and the shortest times about 30 seconds. In general, lower quality green teas are steeped hotter and longer, while higher quality teas are steeped cooler and shorter. Steeping green tea too hot or too long will result in a bitter, astringent brew for low quality leaves. High quality green teas can be and usually are steeped multiple times; 2 or 3 steepings is typical. The brewing technique also plays a very important role to avoid the tea developing an overcooked taste. Preferably, the container in which the tea is steeped or teapot should also be warmed beforehand so that the tea does not immediately cool down.

Caffeine

Unless specifically decaffeinated, green tea contains caffeine.[2] Normal green tea itself may contain more caffeine than coffee, but the length of infusion with hot water and the amount of time the green tea leaves are used can greatly alter caffeine intake.[2] Experiments have shown after the first 5 minutes of brewing, green tea contains 32 mg caffeine.[2] But if the same leaves are then used for a second and then a third five minute brew, the caffeine drops to 12 mg and then 4 mg.[2]

While coffee and tea are both sources of caffeine, the amounts of caffeine in any single serving of these beverages varies significantly. An average serving of coffee contains the most caffeine, yet the same serving size of tea provides only 1/2 to 1/3 as much.[3] One of the more confusing aspects of caffeine content is the fact that coffee contains less caffeine than tea when measured in its dry form. The caffeine content of a prepared cup of coffee is significantly higher than the caffeine content of a prepared cup of tea.[4]

Green teas contain two caffeine metabolites (caffeine-like substances): theophylline, which is stronger than caffeine, and theobromine, which is slightly weaker than caffeine.[citation needed]

Health effects

Green tea contains polyphenols which are thought to improve health, particularly catechins, the most abundant of which is epigallocatechin gallate. In vitro and animal studies as well as preliminary observational and clinical studies of humans suggest that green tea can reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer as well as beneficially impact bone density, cognitive function, dental cavities, and kidney stones. However, the human studies are sometimes mixed and inconsistent.[5] Green tea also contains carotenoids, tocopherols, ascorbic acid (vitamin C), minerals such as chromium, manganese, selenium or zinc, and certain phytochemical compounds. It is a more potent antioxidant than black tea,[5] although black tea has substances which green tea does not such as theaflavin.

Green tea consumption is epidemiologically associated with reduced heart disease, and animal studies have found that it can reduce cholesterol. However, several small, brief human trials found that tea consumption did not reduce cholesterol in humans. In 2003 a randomized clinical trial found that a green tea extract with added theaflavin from black tea reduced cholesterol.[6]

In a study performed at Birmingham (UK) University, it was shown that average fat oxidation rates were 17% higher after ingestion of green tea Extract than after ingestion of a placebo.[7] Similarly the contribution of fat oxidation to total energy expenditure was also significantly higher by a similar percentage following ingestion of green tea extract. This implies that ingestion of green tea extract can not only increase fat oxidation during moderately intensive exercise but also improve insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in healthy young men.

A recent study looked at the effects of short term green tea consumption on a group of students between the ages of 19- 37. Participants were asked not to alter their diet and to drink 4 cups of green tea per day for 14 days. The results showed that short term consumption of commercial green tea reduces systolic and diastolic BP, fasting total cholesterol, body fat and body weight. These results suggest a role for green tea in decreasing established potential cardiovascular risk factors. This study also suggests that reductions may be more pronounced in the overweight population where a significant proportion are obese and have a high risk of cardiovascular disease.[8]

In a study performed at the Technion, it was shown that the main antioxidant polyphenol of green tea extract, EGCG, when fed to mice induced with Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease, helped to protect brain cells from dying, as well as 'rescuing' already damaged neurons in the brain, a phenomenon called neurorescue or neurorestoration. The findings of the study, led by Dr. Silvia Mandell, were presented at the Fourth International Scientific Symposium on Tea and Human Health in Washington D.C., in 2007. Resulting tests underway in China, under the auspices of the Michael J. Fox Foundation, are being held on early Parkinson's patients.[9]

In a recent case-control study of the eating habits of 2,018 women, consumption of mushrooms and green tea was linked to a 90% lower occurrence of breast cancer.[10]

History

Tea consumption had its origin in China more than 4000 years ago.[11] Green tea has been used as both a beverage and a method of traditional medicine in most of Asia, including China, Japan, Vietnam, Korea, India and Thailand, to help everything from controlling bleeding and helping heal wounds to regulating body temperature, blood sugar and promoting digestion.

The Kissa Yojoki (Book of Tea), written by Zen priest Eisai in 1191, describes how drinking green tea can have a positive effect on the five vital organs, especially the heart. The book discusses tea's medicinal qualities, which include easing the effects of alcohol, acting as a stimulant, curing blotchiness, quenching thirst, eliminating indigestion, curing beriberi disease, preventing fatigue, and improving urinary and brain function. Part One also explains the shapes of tea plants, tea flowers, and tea leaves, and covers how to grow tea plants and process tea leaves. In Part Two, the book discusses the specific dosage and method required for individual physical ailments.

Unproven claims

Green tea has been credited with providing a wide variety of health benefits, many of which have not been validated by scientific evidence. These claims and any for which academic citations are currently missing are listed here:

- Stopping certain neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

- The prevention and treatment of cancer.[12][13]

- Treating multiple sclerosis.[14]

- Preventing the degradation of cell membranes by neutralizing the spread of free radicals which occur during oxidation process.[15][dubious – discuss]

- Reducing the negative effects of LDL cholesterol (bad cholesterol) by lowering levels of triglycerides and increasing the production of HDL cholesterol (good cholesterol).

- Joy Bauer, a New York City nutritionist, says [the catechins in green tea] increase levels of the metabolism speeding brain chemical norepinephrine (noradrenaline).

- Japanese researchers claim that drinking five cups of green tea a day can burn 70 to 80 extra calories. Dr. Nicholas Perricone, a self-proclaimed anti-aging specialist, appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show and told Oprah's viewers they can lose 10 lbs (4.5 kg) in 6 weeks drinking green tea instead of coffee.

- Some green tea lovers commonly restrict their intake because of the stimulants it contains — equivalent to about a third the amount of caffeine as is found in coffee[4][dubious – discuss]. Too much caffeine can cause nausea, insomnia, or frequent urination.[16]

United States Food and Drug Administration

The article Tea: A Story of Serendipity[17] appeared in the March 1996 issue of the United States Food and Drug Administration Consumer Magazine and looked at the potential benefits of green tea. At that time they had not done any reviews of the potential benefits of green tea and were waiting to do so until health claims were filed. They have since denied two petitions to make qualified health claims as to the health benefits of green tea.[18]

On June 30, 2005, in response to "Green Tea and Reduced Risk of Cancer Health Claim", they stated: "FDA concludes that there is no credible evidence to support qualified health claims for green tea consumption and a reduced risk of gastric, lung, colon/rectal, esophageal, pancreatic, ovarian, and combined cancers. Thus, FDA is denying these claims. However, FDA concludes that there is very limited credible evidence for qualified health claims specifically for green tea and breast cancer and for green tea and prostate cancer, provided that the qualified claims are appropriately worded so as to not mislead consumers." [19]

On May 9, 2006, in response to "Green Tea and Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease", they concluded "there is no credible evidence to support qualified health claims for green tea or green tea extract and a reduction of a number of risk factors associated with CVD." [20]

However in October 2006, the FDA approved an ointment based on green tea. New Drug Application (NDA) number N021902, for kunecatechins ointment 15% (proprietary name Veregen) was approved on October 31, 2006,[21] and added to the "Prescription Drug Product List" in October 2006.[22] Kunecatechins ointment is indicated for the topical treatment of external genital and perianal warts.[23]

Scientific studies

According to research reported at the Sixth International Conference on Frontiers in Cancer Prevention, sponsored by the American Association for Cancer Research, a standardized green tea polyphenol preparation (Polyphenon E) limits the growth of colorectal tumors in rats treated with a substance that causes the cancer. "Our findings show that rats fed a diet containing Polyphenon E are less than half as likely to develop colon cancer," Dr. Hang Xiao, from the Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy at Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey, noted in a statement.

A 2006 study published in the September 13 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association concluded "Green tea consumption is associated with reduced mortality due to all causes and due to cardiovascular disease but not with reduced mortality due to cancer." The study, conducted by the Tohoku University School of Public Policy in Japan, followed 40,530 Japanese adults, ages 40–79, with no history of stroke, coronary heart disease, or cancer at baseline beginning in 1994. The study followed all participants for up to 11 years for death from all causes and for up to 7 years for death from a specific cause. Participants who consumed 5 or more cups of tea per day had a 16 percent lower risk of all-cause mortality and a 26 percent lower risk of cardiovascular disease ("CVD") than participants who consumed less than one cup of tea per day. The study also states, "If green tea does protect humans against CVD or cancer, it is expected that consumption of this beverage would substantially contribute to the prolonging of life expectancy, given that CVD and cancer are the two leading causes of death worldwide."[24] [25]

A study in the February 2006 edition of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition concluded "A higher consumption of green tea is associated with a lower prevalence of cognitive impairment in humans."[26][27][dubious – discuss]

In May 2006, researchers at Yale University School of Medicine weighed in on the issue with a review article that looked at more than 100 studies on the health benefits of green tea. They pointed to what they called an "Asian paradox," which refers to lower rates of heart disease and cancer in Asia despite high rates of cigarette smoking. They theorized that the 1.2 liters of green tea that is consumed by many Asians each day provides high levels of polyphenols and other antioxidants. These compounds may work in several ways to improve cardiovascular health, including preventing blood platelets from sticking together (This anticoagulant effect is the reason doctors warn surgical patients to avoid green tea prior to procedures that rely on a patient's clotting ability) and improving cholesterol levels, said the researchers, whose study appeared in the May issue of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons. Specifically, green tea may prevent the oxidation of LDL cholesterol (the "bad" type), which, in turn, can reduce the buildup of plaque in arteries, the researchers wrote.[28]

A study published in the August 22, 2006 edition of Biological Psychology looked at the modification of the stress response via L-Theanine, a chemical found in green tea. It "suggested that the oral intake of L-Theanine could cause anti-stress effects via the inhibition of cortical neuron excitation."[29]

In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted by Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, 240 adults were given either theaflavin-enriched green tea extract in form of 375 mg capsule daily or a placebo. After 12 weeks, patients in the tea extract group had significantly less low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and total cholesterol (16.4% and 11.3% lower than baseline, p<0.01) than the placebo group. The author concluded that theaflavin-enriched green tea extract can be used together with other dietary approaches to reduce LDL-C.

A study published in the January, 2005 edition of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition concluded "Daily consumption of tea containing 690 mg catechins for 12 wk reduced body fat, which suggests that the ingestion of catechins might be useful in the prevention and improvement of lifestyle-related diseases, mainly obesity." [30]

According to a Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine study published in the April 13 2005 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, antioxidants in green tea may prevent and reduce the severity of rheumatoid arthritis. The study examined the effects of green tea polyphenols on collagen-induced arthritis in mice, which is similar to rheumatoid arthritis in humans. In each of three different study groups, the mice given the green tea polyphenols were significantly less likely to develop arthritis. Of the 18 mice that received the green tea, only eight (44 percent) developed arthritis. Among the 18 mice that did not receive the green tea, all but one (94 percent) developed arthritis. In addition, researchers noted that the eight arthritic mice that received the green tea polyphenols developed less severe forms of arthritis.

A German study found that an extract of green tea and hot water (filtered), applied externally to the skin for 10 minutes, three times a day could help people with skin damaged from radiation therapy (after 16–22 days).[31]

A study published in the December 1999 American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that "Green tea has thermogenic properties and promotes fat oxidation beyond that explained by its caffeine content per se. The green tea extract may play a role in the control of body composition via sympathetic activation of thermogenesis, fat oxidation, or both."[32]

In lab tests, EGCG, found in green tea, was found to prevent HIV from attacking T-Cells. However, it is not yet known if this has any effect on humans.[33]

A study in the August, 2003 issue of a new potential application of Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences found that "a new potential application of (–)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate [a component of green tea] in prevention or treatment of inflammatory processes is suggested" [34]

However, pharmacological and toxicological evidence does indicate that green tea polyphenols can in fact cause oxidative stress and liver toxicity in vivo at certain concentrations.[35] This would imply that consumers should exercise caution when consuming herbal products produced from concentrated green tea extract. Other evidence presented in the review cautions against the drinking of green tea by pregnant women.[36]

Drug Interactions

A 2009 study at the University of Southern California using mouse models showed that several of the polyphenolic ingredients of green tea, such as EGCG, can bind with the anticancer drug bortezomib, significantly reducing its bioavailability and thereby rendering it therapeutically useless.[37] This chemical reaction between EGCG and bortezomib is highly specific and depends on the presence of a boronic acid functional group in the bortezomib molecule. Dr. Schönthal, who headed the study, suggests that consumption of green tea, concentrated green tea extract, and other green tea products (such as EGCG capsules) be strongly contraindicated for patients undergoing bortezomib treatment.[38]

Safety

In 2008 the US Pharmacopeia reviewed the safety. It found 216 case reports, 34 on liver damage, of which 27 were categorized as possible and 7 were categorized as probable. Potential for adverse effects is increased when extracts are used, particularly on an empty stomach.[39]

See also

- Chinese tea culture

- Japanese tea ceremony

- Potential effects of tea on health

- Reactive oxygen species

- Yellow tea

- Korean tea

- White tea

References

- ^ "Green Tea's Cancer-fighting Allure Becomes More Potent".

- ^ a b c d http://www.medicinalfoodnews.com/vol10/2006/green_tea

- ^ Caffeine & Health: Clarifying the Controversies, IFIC Review, 2007

- ^ http://www.stashtea.com/caffeine.htm

- ^ a b Cabrera C, Artacho R, Giménez R (2006). "Beneficial effects of green tea--a review". J Am Coll Nutr. 25 (2): 79–99. PMID 16582024.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Maron DJ, Lu GP, Cai NS; et al. (2003). "Cholesterol-lowering effect of a theaflavin-enriched green tea extract: a randomized controlled trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (12): 1448–53. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.12.1448. PMID 12824094.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Green tea extract ingestion, fat oxidation, and glucose tolerance in healthy humans". Vol. 87, No. 3. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008. pp. 778–784. Retrieved 2008-10-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Zhang, M (2009). "Dietary intakes of mushrooms and green tea combine to reduce the risk of breast cancer in Chinese women". International Journal of Cancer. 124 (6). International Journal of Cancer (Online): 1404–1408. doi:10.1002/ijc.24047.

- ^ About.com. The History of Tea - Tea Bags and Makers

- ^ The combination of green tea and tamoxifen is effe...[Carcinogenesis. 2006] - PubMed Result

- ^ BBC news - 17 March 2009 - green tea may have the power to ward off breast cancer

- ^ A New Function of Green Tea: Prevention of Lifestyle-related Diseases - Sueoka et al. 928 (1): 274 - Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences

- ^ Green Tea Health Benefits

- ^ ACS :: Green Tea

- ^ Tea: A Story of Serendipity

- ^ Qualified health claim definition - Medical Dictionary definitions of popular medical terms easily defined on MedTerms

- ^ US FDA/CFSAN - Letter Responding to Health Claim Petition dated January 27, 2004: Green Tea and Reduced Risk of Cancer Health Claim (Docket number 2004Q-0083)

- ^ US FDA/CFSAN - Qualified Health Claims: Letter of Denial - Green Tea and Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (Docket No. 2005Q-0297)

- ^ CDER New Molecular Entity (NME) Drug and New Biologic Approvals in Calendar Year 2006

- ^ Prescription and Over-the-Counter Drug Product List: 10/2006

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2006/021902lbl.pdf

- ^ JAMA - Abstract: Green Tea Consumption and Mortality Due to Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and All Causes in Japan: The Ohsaki Study, September 13, 2006, Kuriyama et al. 296 (10): 1255

- ^ http://www.denverpost.com/nationworld/ci_4326770 Article in the Denver Post

- ^ Green tea consumption and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study from the Tsurugaya Project 1 - Kuriyama et al. 83 (2): 355 - American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- ^ Green tea could protect against Alzheimer's

- ^ Green Tea and the “Asian Paradox”

- ^ L-Theanine reduces psychological and physiological...[Biol Psychol. 2007] - PubMed Result

- ^ Ingestion of a tea rich in catechins leads to a reduction in body fat and malondialdehyde-modified LDL in men - Nagao et al. 81 (1): 122 - American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- ^ Studies: Green Tea May Help Prolong Life, Senay: Research Also Shows Benefits For Skin, Few Drawbacks - CBS News

- ^ Efficacy of a green tea extract rich in catechin polyphenols and caffeine in increasing 24-h energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans - Dulloo et al. 70 (6): 1040 - American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

- ^ Green Tea Blocks HIV in Test Tubes

- ^ SpringerLink - Journal Article

- ^ [3] Lambert, J.D., et al., (2007) Possible Controversy over Dietary Polyphenols: Benefits vs Risks, Chem Res Toxicol

- ^ Strick; et al. (2000). "Dietary bioflavonoids induce cleavage in the MLL gene and may contribute to infant leukemia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97: 4790–4795. PMID 10758153.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Golden, E. (2009). "Green tea polyphenols block the anticancer effects of bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors". Blood. 113: 5927–5937. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-171389. PMID 19190249.

- ^ Neith, Katie. "Green tea blocks benefits of cancer drug, study finds". Retrieved 2009-02-04.

- ^ Sarma DN, Barrett ML, Chavez ML; et al. (2008). "Safety of green tea extracts : a systematic review by the US Pharmacopeia". Drug Saf. 31 (6): 469–84. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831060-00003. PMID 18484782.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Literature

- Master Lam Kam Cheun; et al. (2002). The way of tea. Gaia Books. ISBN 1856751430.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)