St. Augustine, Florida: Difference between revisions

| Line 448: | Line 448: | ||

* [http://www.staugustinepics.com St. Augustine Pics] Daily pictures of St. Augustine, Florida. |

* [http://www.staugustinepics.com St. Augustine Pics] Daily pictures of St. Augustine, Florida. |

||

* [http://ibistro.dos.state.fl.us/uhtbin/cgisirsi/x/x/0/5?library=PHOTO&item_type=PHOTOGRAPH&searchdata1=twine%20collection Twine Collection] Over 100 images of the St. Augustine community of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida. |

* [http://ibistro.dos.state.fl.us/uhtbin/cgisirsi/x/x/0/5?library=PHOTO&item_type=PHOTOGRAPH&searchdata1=twine%20collection Twine Collection] Over 100 images of the St. Augustine community of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida. |

||

* St. Augustine Images [http://augustine.info/gallery/main.php/historic_photographs/ Historic Images of St. Augustine] An online archive of historical images of St. Augustine, including Flagler's hotels, the plaza, government building, sea wall, Fort, and more. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 17:32, 28 September 2010

City of St. Augustine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): Ancient City, Old City | |

Location in St. Johns County and the state of Florida | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Established | 1565 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Joseph L. Boles |

| Area | |

| • City | 27.8 km2 (10.7 sq mi) |

| • Land | 21.7 km2 (8.4 sq mi) |

| • Water | 6.1 km2 (2.3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1.52 m (4.99 ft) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • City | 12,284 |

| • Density | 534.7/km2 (1,385/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,277,997 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Area code | 904 |

| Website | http://www.staugustinegovernment.com/ |

Template:Fix bunching St. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States.Template:GR Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the United States.[1] St. Augustine lies in a region of Florida known as "The First Coast", which extends from Amelia Island in the north to Jacksonville, St. Augustine and Palm Coast in the south. According to the 2000 census, the city population was 11,592; in 2004, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that the population had reached 12,157.[2] St. Augustine is the headquarters for the Florida National Guard.

History

Early exploration and attempts at settlement

The vicinity of St. Augustine was first explored in 1513 by Spanish explorer and governor of Puerto Rico, Ponce de Leon, who claimed the region for the Spanish crown.[3] Prior to the founding of St. Augustine in 1565, several earlier attempts at European colonization in what is now Florida were made by both Spain and France, but all failed.

The French exploration of the area began in 1562 under the Huguenot captain Jean Ribault, sailing under orders from Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. Ribault's expedition departed from France in February 1562; he explored the St. Johns River to the north of St. Augustine before sailing north. Ribault established the settlement of Charlesfort on Parris Island in present-day South Carolina before returning to France for supplies; however, the settlers abandoned Charlesfort before he could return. In 1564 Ribault's lieutenant René Goulaine de Laudonnière launched a new colonization effort, ultimately selecting the St. Johns River as the location of the new settlement of Fort Caroline. Laudonnière explored the North Florida area much more thoroughly, entering through the St. Augustine Inlet into the Matanzas River, which he named the River of Dolphins.[4]

In 1564 some mutineers from Fort Caroline fled the colony and turned pirate, attacking Spanish vessels in the Caribbean. The Spanish used this as a catalyst to locate and destroy Fort Caroline, fearing it would serve as a base for future piracy and wanting to dissuade French colonization. The Spanish quickly dispatched Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to go to Florida and establish a base from which to attack the French.[1]

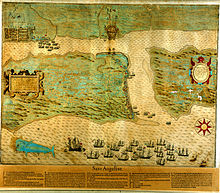

Founding of St. Augustine

Pedro Menéndez de Avilés sighted land on August 28, 1565. As this was the feast day of Augustine of Hippo, the territory was named San Agustín. The Spanish sailed through St. Augustine inlet into Matanzas Bay and disembarked near the Timucua town of Seloy on September 7.[5][6][7][8][9] Menéndez's goal was to dig a quick fortification to protect his people and supplies as they were unloaded from the ships, and then to take a more proper survey of the area to determine the best location for the fort. The location of this early fort is unknown, but may be at the grounds of what is now the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park. It is known that the Spanish occupied several structures in Seloy, the chief of which, known as Chief Seloy, was friendly with the Saturiwa, Laudonnière's allies. It is possible, but undemonstrated, that Menéndez fortified one of the occupied Timucua structures as this first fort at Seloy.[5]

In the meantime, Jean Ribault, Laudonnière's old commander, arrived at Fort Caroline with more settlers for the colony, as well as soldiers and weapons to defend them. He also took over the governorship of the settlement. Despite Laudonnière's wishes Ribault put most of these soldiers aboard his ships for an assault on St. Augustine. However, he was surprised at sea by a violent storm lasting several days. This gave Menéndez the opportunity to march his forces overland and make a surprise dawn attack on the Fort Caroline garrison, which then numbered several hundred people. Laudonnière and some survivors fled to the woods, and the Spanish killed most everyone in the fort except for the women and children. With the French displaced, Menéndez rechristened the fort as San Mateo, and appropriated it for his own purposes. Returning south, the Spanish encountered the survivors of Ribault's fleet near the inlet at the southern end of Anastasia Island and executed most of them, including Ribault. Thus the inlet was named for the Spanish word for slaughters, matanzas.

The 1565 founding of San Agustín (St. Augustine) makes this city the first permanent European settlement in what would later become the continental United States. In 1566, Martín de Argüelles was born in San Agustín, the first European child who was recorded as born in the continental United States. Argüelles was born in San Agustín 21 years before the English settlement at Roanoke Island in Virginia Colony, and 42 years before the successful settlements of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Jamestown, Virginia.

Additionally, the first recorded birth of a black child in the continental United States is in the Cathedral Parish Archives. Augustin was recorded as born in the year 1606, thirteen years before enslaved Africans were first brought to the English colony at Jamestown in 1619. In territory under the jurisdiction of the United States, only European-established settlements in Puerto Rico are older than St. Augustine.

Spanish rule

There were no further permanent organized non-Spanish settlements in the Americas for several decades. St. Augustine remained the sole European settlement in the continental United States and a forward outpost guarding the Spanish Americas. Its importance to Spain in helping to crush any Protestant and non-Spanish settlements along the Atlantic coasts in turn caused it to be the focus of competing Protestant and European interests. Therefore, French and later English attacks were later made on St. Augustine which came to represent in the eyes of the Protestant countries the epitome of Catholic cruelty and ambition. Thus, first the Protestant French and later the English made attacks and even occupations of St. Augustine.

Following the destruction of the French Carolina colony, the French immediately launched reprisals. Although the Spanish destroyed Fort Caroline, they built their own fort on the same site. Realizing that St. Augustine was too close to Spanish reinforcements, the French first attempted to retake Fort Caroline. In April 1568, Dominique de Gourgues led a French force which attacked, captured and burned the fort. He then slaughtered all his Spanish prisoners in horrible revenge for the 1565 massacre.[1] However, the Spanish forces in Florida were superior and managed to drive the French naval expedition out of the area. The Spanish rebuilt, but permanently abandoned the fort the following year. Additional French expeditions were primarily raids and were unable to dislodge the Spanish from St. Augustine.

The English also believed Admiral Avilés and the Catholic Spanish were responsible for the disappearance of the English fishing settlements in America which had been established by John Cabot. Thus, following the disappearance of the Roanoke colony in Virginia, the blame was immediately leveled at St. Augustine. Consequently, in 1586 St. Augustine is attacked and burned by English privateer Sir Francis Drake and the surviving Spanish settlers were driven into the wilderness. However, lacking sufficient forces or authority for permanently establishing a settlement, Drake left the area.

In 1668 St. Augustine was attacked and plundered by English privateer Robert Searle. In the aftermath of his raid, the Spanish began in 1672 the construction of a more secure fortification, the Castillo de San Marcos, which still stands today as the nation's oldest fort. Its construction took a quarter of a century, with many later additions and modifications.

The Spanish didn't have as many slaves in Florida as the English Americans had in their colonies to the north, as it was basically a military outpost rather than a plantation economy. As the British settlements moved farther and farther south, the Spanish adopted the policy of giving sanctuary to slaves who could escape from British plantations and make their way to Florida. Thus did it become the focal point of the first Underground Railroad. Blacks were given sanctuary, arms, and supplies if they would join the Catholic Church and swear allegiance to the king of Spain.

As the British established settlements closer to Spanish territory, with Charleston in 1670 and Savannah in 1733, Spanish Governor Manual de Montiano in 1738 established the first legally recognized free community of ex-slaves as the northern defense of St. Augustine, known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, or Fort Mose.

In 1740 St. Augustine was unsuccessfully attacked by British forces from their colonies in the Carolinas and Georgia. The largest and most successful of these was organized by Governor and General James Oglethorpe of Georgia who managed to break the Spanish-Seminole alliance when he gained the help of Ahaya the Cowkeeper, chief of the Alachua band of the Seminole tribe.

In the subsequent campaign Oglethorpe, supported by several thousand colonial militia and British regulars along with Seminole warriors, invaded Spanish Florida and conducted the Siege of St. Augustine during the War of Jenkin's Ear. During this siege the black community of St. Augustin proved its worth when during the siege it proved decisive in stopping the city's take-over by the British. The leader of Fort Mose during the battle was the legendary Capt. Francisco Menendez (creole), who was born in Africa, twice escaped from slavery, and played an important role in defending St. Augustine from raid by British colonists to the north. The Fort Mose site is now owned by the Florida Park Service, and recognized as a National Historic Landmark.

British rule

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris ended the French and Indian War and gave Florida and St. Augustine to the British, in exchange for the British relinquishing control of occupied Havana. With the change of flags, almost all of the population of 3,100 Spaniards departed from St. Augustine.

James Grant was appointed the first governor of East Florida, and would serve from 1764 until 1771 when he returned to Britain due to illness. He was replaced as governor by Patrick Tonyn.

During this time the British converted the monks quarters of the former Franciscan monastery into military barracks which were named St. Francis Barracks. They also built The King's Bakery which is believed to be the only extant structure in the city built entirely in British period.

The Lieutenant Governor of East Florida under Governor Grant was John Moultrie who was born in South Carolina, he had served under Grant as a major in the Cherokee War and remained loyal to the British Crown. Moultrie's brother William Moultrie of whom Fort Moultrie in South Carolina is named was a general in the Continental Army. His brother Thomas was a captain in the American 2nd South Carolina Regiment who was killed in the Battle of Charleston, while his half-brother Alexander became the first Attorney General in South Carolina and was held prisoner in St. Augustine while John was acting British Lieutenant Governor. Moultrie was granted large tracts of land in the St. Augustine vicinity upon which he established the plantation of "Bella Vista" he owned another 2,000 acre plantation in the Tomoka River basin named "Rosetta". While acting as the lieutenant governor he lived in the Peck House on St. George St.

Another large development effort during the British period was the establishment in 1768 of the colony of New Smyrna, by Dr. Andrew Turnbull a friend of Grants. Turnbull recruited indentured servants from the Mediterranean, primarily from the island of Minorca. The conditions at New Smyrna were abysmal, prompting the settlers to rebel en masse in 1777 and walk the 70 miles to St. Augustine , where Grant gave them refuge.

The story of the Minorcan colony (as the entire group came to be known) is told, fictionally, in the book Spanish Bayonet by Stephen Vincent Benet, a prominent descendant of one of the leading Minorcan families of St. Augustine. The Minorcans, stayed on in St. Augustine through all the subsequent changes of flags, to become the venerable families of the community, marking it with language, culture, cuisine and customs.

Second Spanish rule

The Treaty of Paris in 1783, gave the American colonies north of Florida their independence, and ceded Florida to Spain in recognition of Spanish efforts on behalf of the American colonies during the war.

On 3 September of 1783, by Treaty of Paris, Britain also signed separate agreements with France and Spain, and (provisionally) with the Netherlands. In the treaty with Spain, the colonies of West Florida, captured by the Spanish, and East Florida were returned to Spain, as was the island of Minorca, while the Bahama Islands, Grenada and Montserrat, captured by the French and Spanish, were returned to Britain.

Florida was under Spanish control again from 1781 to 1821, but St. Augustin since 1784. During this time, Spain was being invaded by Napoleon between 1808 and 1814 and was struggling to retain its colonies. Florida no longer held its past importance to Spain, thus, in 1821 the Adams-Onís Treaty peaceably turned the Spanish colonies in Florida and, with them, St. Augustine, over to the United States as a way of compensating the American government for the civil claims that were in part caused by undefined border areas with Spanish territories.

American Rule

Florida was ceded to the United States by Spain in the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty, ratification of the treaty took place in 1821 and it officially became a U.S. possession as the Florida Territory, in 1822, with future president Andrew Jackson as the first territorial governor. It would gain statehood in 1845.

In 1861, the American Civil War began and Florida seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy. On January 7, 1861, prior to Florida's formal secession, a local militia unit, the St. Augustine Blues, took possession of St. Augustine's military facilities, including Fort Marion and the St. Francis Barracks, from the lone Union ordnance sergeant on duty.

Crew from the USS Wabash reoccupied the city for the United States government without opposition on March 11, 1862 and it would remain under union control throughout the war. In 1865, Florida rejoined the United States.

After the war, former slaves in St. Augustine established the community of Lincolnville in 1866, named after President Abraham Lincoln. Lincolnville with the largest concentration of Victorian Era homes in St. Augustine, would also be a key setting for the Civil Rights Movement a century latter.

Fort Marion: When the Americans took possession of Florida in 1821, they renamed the Castillo de San Marcos (British, Fort St. Marks), Fort Marion, after Francis Marion the "Swamp Fox" of the American Revolution.

During the Second Seminole War of 1835-1842 the fort served as a prison for Seminole captives including the famed leader Osceola, the black Seminole, John Cavallo (John Horse) as well as Coacoochee (Wildcat), who would make a daring escape from the fort with 19 other Seminoles.

After the Civil War it was used twice, in the 1870s and then again in the 1880s, to house first Plains Indians and then Apaches who were captured in the west. The daughter of Geronimo was born at Fort Marion, and was named Marion, though she later chose to change that. The fort was also used as a military prison during the Spanish-American War of 1898. It was finally removed from the Army's active duty rolls in 1900 after 205 years of service under five different flags. It is now run by the National Park Service, and called the Castillo de San Marcos National Monument.

Flagler era

Henry Flagler,a partner with John D. Rockefeller in Standard Oil arrived in St. Augustine in the 1880s and was the driving force behind turning the city into a winter resort for the wealthy northern elite.[10] Flagler bought a number of local railroads which were incorporated into the Florida East Coast Railway, which built it's headquarters in St. Augustine.[11]

Flagler contracted the New York architectural firm of Carrère and Hastings to design a number of extravagant buildings in St. Augustine, among them the Ponce de Leon Hotel and the Alcazar Hotel built on land purchased from Flaglers' friend and associate Dr. Andrew Anderson as well as the Memorial Presbyterian Church.

Flagler had Albert Spalding design a baseball park in St. Augustine, and the waiters at his hotels, under the leadership of Frank P. Thompson, formed one of America's pioneer professional black baseball teams, the Ponce de Leon Giants. It later became the Cuban Giants, and one of the team members, Frank Grant, has been inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Civil rights movement

St. Augustine was a pivotal site for the Civil Rights Movement in 1963[12] and 1964.[13]

Efforts by African Americans to integrate the public schools and public accommodations such as lunch counters were met with arrests and Ku Klux Klan violence. Non-violent protesters were arrested for participating in peaceful picket lines, sit-ins, and marches. Homes were firebombed, black leaders were assaulted and threatened with death, and fired from their jobs.[14]

In the spring of 1964, St. Augustine NAACP leader Dr. Robert Hayling asked the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and its leader Martin Luther King, Jr. for assistance. From May until July 1964, they carried out marches, sit-ins, and other forms of peaceful protest took place in St. Augustine.

Hundreds of black and white civil-rights supporters were arrested, and the jails were filled to overflowing. At the request of Dr. Hayling and Dr. King, white civil-rights supporters from the north, including students, clergy, and well-known public figures, came to St. Augustine and were arrested.

The KKK, led by Douglas Schnittker, responded with violent attacks that were widely reported in national and inter-national media. Popular revulsion against the Klan violence generated national sympathy for the black protesters and became a key factor in passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[14]

Modern Era

The city is a popular tourist attraction, for its Spanish Colonial buildings as well as elite 19th century architecture. The city's historic center is anchored by St. George Street, which is lined with historic homes from various periods. Some of these homes are reconstructions on the original site, many are original.

The St. Augustine Alligator Farm, incorporated in 1908, is one of the oldest commercial tourist attractions in Florida, as is the Fountain of Youth, which dates from the same time period. The city is one terminus of the Old Spanish Trail, a promotional effort of the 1920s linking St. Augustine to San Diego, California with 3000 miles of roadways.

Geography and climate

St. Augustine is located at 29°53′39″N 81°18′48″W / 29.89417°N 81.31333°WInvalid arguments have been passed to the {{#coordinates:}} function (29.89785, -81.31151).Template:GR According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.7 square miles (27.8 km²), of which, 8.4 square miles (21.7 km²) of it is land and 2.4 square miles (6.1 km²) of it (21.99%) is water. Access to the Atlantic Ocean is via the St. Augustine Inlet of the Matanzas River.

Hurricanes: In modern times, St. Augustine has mostly been spared the wrath of tropical cyclones. The only direct hit was Hurricane Dora, which came ashore just after midnight on September 10, 1964. Hurricane Donna in 1960, and unnamed hurricanes in 1944 and 1950 also affected the area.

Demographics

As of the 2000 United States Census,Template:GR there were 9,592 people, 4,963 households, and 2,600 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,384.6 people per square mile (534.7/km²). There were 5,642 housing units at an average density of 673.9/sq mi (260.3/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 81.21% Caucasian, 15.07% African American, 0.41% Native American, 0.72% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 0.88% from other races, and 1.61% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.11% of the population.

There were 4,963 households out of which 18.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.4% were married couples living together, 12.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.6% were non-families. 36.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.76.

In the city the population was spread out with 16.1% under the age of 18, 15.3% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 25.2% from 45 to 64, and 19.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 84.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $32,358, and the median income for a family was $41,892. Males had a median income of $27,099 versus $25,121 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,225. About 9.8% of families and 15.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.8% of those under age 18 and 10.0% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

Highways

Interstate 95 runs north-south.

Interstate 95 runs north-south. U.S. Route 1 runs north-south.

U.S. Route 1 runs north-south. Florida State Road 16 runs east-west

Florida State Road 16 runs east-west Florida State Road A1A runs north-south.

Florida State Road A1A runs north-south. Florida State Road 312 runs east-west

Florida State Road 312 runs east-west Florida State Road 207 runs northeast to southwest

Florida State Road 207 runs northeast to southwest

Buses

Bus service is operated by the Sunshine Bus Company. Buses operate mainly between shopping centers across town, but a few go to Hastings and Jacksonville, where one can connect to JTA for additional service across Jacksonville.

Airport

St. Augustine has one public airport 5 miles north of town. It has 5 runways (2 of them water for sea planes), and was once served by Skybus, however Skybus ceased operations as of April 4, 2008. Only private flights and tour helicopters use it today.

Points of interest

Spanish Eras

- Avero House

- Castillo de San Marcos National Monument

- Fort Matanzas National Monument

- Fort Mose Historic State Park

- Nombre de Dios

- Gonzalez-Alvarez House

- Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park

- The Spanish Military Hospital Museum

- St. Francis Barracks

- Spanish Quarter Village

- Ximenez-Fatio House

- Oldest Wooden Schoolhouse

British Era

Pre-Flagler Era

Flagler Era

- Ponce de León Hotel

- Casa Monica Hotel

- Hotel Alcazar

- Zorayda Castle

- Old St. Johns County Jail

- Ripley's Believe it or Not! Museum located in 1887 mansion of William Worden.

- Alligator Farm

Historic Churches

- Grace United Methodist Church

- Cathedral Basilica of St. Augustine

- Memorial Presbyterian Church

- Trinity Church of St. Augustine

Lincolnville National Historic District-Civil Rights Era

- Freedom Trail of Historic Sites of the Civil Rights Movement

- Excelsior School Museum of African American History

- St. Benedict the Moor School

Other

- Anastasia State Park

- Bridge of Lions

- Florida School for the Deaf and Blind

- St. Augustine Amphitheatre

- World Golf Hall of Fame

Sister cities

Education

In 1918 the Florida Baptist Academy moved from Jacksonville to St. Augustine, and became the first college. Over the years it was known as Florida Normal, then Florida Memorial College, before it moved to Miami in 1968. It made a major impact on the community while it was here, providing cultural activities, job training and employment for the black community. During World War II it was chosen as the site for training the first blacks in the U. S. Signal Corps. Among its faculty members was Zora Neale Hurston, the famous novelist and anthropologist. There is now a historic marker on the house where she lived at 791 West King Street (were she wrote her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road).

- St. Johns County School District operates local public schools

- Flagler College, a four year liberal arts college

- Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind, a public residential school operated by the state of Florida, was founded in 1885 and is located in St. Augustine[15]

- St. Johns River Community College

- St. Joseph Academy, founded in 1866, is the oldest Catholic high school in Florida

- University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, graduate institution for health sciences[16]

Notable residents

- Andrew Anderson, doctor, former St. Augustine mayor

- Jim Albrecht, poker tournament director and commentator

- Murray Armstrong, hockey coach

- Jorge Biassou, Haitian revolutionary, and America's first black general

- Richard Boone, actor

- Ray Charles, pianist

- Alexander Darnes, born a slave, became a celebrated physician

- Frederick Delius, composer

- Henry Flagler, industrialist

- Willie Galimore, football player

- William H. Gray, U. S. congressman and president of the United Negro College Fund

- Louise Homer, opera star

- Sidney Homer, composer

- Lindy Infante, professional (American) football coach

- Stetson Kennedy, author

- Jack Temple Kirby, historian

- Scott Lagasse Jr., race car driver

- John C. Lilly, dolphin scientist

- Mary MacLane, author

- Albert Manucy, historian, author, Fulbright Scholar

- George McGovern, U. S. senator, presidential candidate

- Johnny Mize, Hall of Fame baseball player

- Prince Achille Murat, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

- David Nolan, author and historian

- Osceola, Seminole War leader (held prisoner at Fort Marion, now Castillo de San Marcos)

- Tom Petty, rock musician

- Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, novelist

- Marcus Roberts, musician

- Richard Henry Pratt, soldier and educator

- Scott Player, pro (American) football punter

- Steve Spurrier, college/pro (American) football coach

- Jack D. Hunter, novelist, author of The Blue Max

- Edmund Kirby Smith, Confederate general

- John M. Schofield, Union general

- William W. Loring, Confederate general

- Edmund Jackson Davis, governor

- Tom Gabel, singer

- Travis Tomko, pro wrestler

- Gamble Rogers, folksinger

- Martin Johnson Heade, artist

- Zora Neale Hurston, novelist and folklorist

- Earl Cunningham, artist

- Willie Irvin, pro (American) football player

- James Branch Cabell, novelist

- Doug Carn, jazz musician

- Felix Varela, Cuban national hero

- Tim Tebow, college (American) football player

- Howell W. Melton, United States district dudge

- Cris Carpenter, baseball player

- Howell W. Melton Jr., attorney, law firm managing partner

- Peter Taylor, novelist

- Jacob Lawrence, artist

- David Levy Yulee, First Jewish US Senator, Levy County and Yulee, Florida namesake

- Stephen Farrelly, pro wrestler

Gallery

-

St. Augustine waterfront with Castillo de San Marcos in distance (1860's).

-

Government House as seen from the Town Plaza c. 1861-1865

-

Historic Huguenot Cemetery

-

Tovar House, 22 St. Francis St.

-

Castillo de San Marcos, Civil War era.

References

- ^ a b National Historic Landmarks Program - St. Augustine Town Plan Historic District

- ^ Table 4: Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places in Florida, Listed Alphabetically: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2004

- ^ Lawson, pp. 29-32

- ^ George M. Brown, Ponce de Leon Land and Florida War Record, p. 99

- ^ a b "Menendez Fort and Camp". www.flmnh.ufl.edu. Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ Florida Museum of Natural History

- ^ US National Park Service - Experience Your America.

- ^ The making of urban America: a history of city planning in the United States by John W. Reps p. 33 Publisher: Princeton University Press (1992) Language: English ISBN 0691006180

- ^ Menéndez: Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Captain General of the Ocean Sea by Albert C. Manucy p. 33 Publisher: Pineapple Press (1992) Language: English ISBN 1561640158

- ^ Henry Flagler, Builder of Florida By Sandra Wallus Sammons p. 16

- ^ The Conductor and brakeman, Volume 18 By Order of Railway Conductors and Brakemen p.17

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "St. Augustine FL, Movement — 1963".

- ^ Civil Rights Movement Veterans. "St. Augustine FL, Movement — 1964".

- ^ a b Branch, Taylor (1998). Pillar of Fire. Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind website

- ^ University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences

Additional reading

- Abbad y Lasierra, Iñigo, "Relación del descubrimiento, conquista y población de las provincias y costas de la Florida" - "Relación de La Florida" (1785); edición de Juan José Nieto Callén y José María Sánchez Molledo.

- Colburn, David, Racial Change and Community Crisis: St. Augustine, Florida, 1877-1980 (1985), New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deagan, Kathleen, Fort Mose: Colonial America's Black Fortress of Freedom (1995), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Fairbanks, George R. (George Rainsford), History and antiquities of St. Augustine, Florida (1881), Jacksonville, Fla., H. Drew.

- Gannon, Michael V., The Cross in the Sand: The Early Catholic Church in Florida 1513-1870 (1965), Gainesville: University Presses of Florida.

- Graham, Thomas, The Awakening of St. Augustine, (1978), St. Augustine Historical Society

- Harvey, Karen, America's First City, (1992), Lake Buena Vista, FL: Tailored Tours Publications.

- Landers, Jane, Black Society in Spanish Florida (1999), Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Lyon, Eugene, The Enterprise of Florida, (1976), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Manucy, Albert, Menendez, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

- Nolan, David, Fifty Feet in Paradise: The Booming of Florida, (1984), New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Nolan, David, The Houses of St. Augustine, (1995), Sarasota, Fla.: Pineapple Press.

- Porter, Kenneth W., The Black Seminoles: History of a Freedom-Seeking People, (1996), Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Reynolds, Charles B. (Charles Bingham), Old Saint Augustine, a story of three centuries, (1893), St. Augustine, Fla. E. H. Reynolds.

- Torchia, Robert W., Lost Colony: The Artists of St. Augustine, 1930-1950, (2001), St. Augustine: The Lightner Museum.

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965. Law Enforcement: A Report on Equal Protection in the South. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Warren, Dan R., If It Takes All Summer: Martin Luther King, the KKK, and States' Rights in St. Augustine, 1964, (2008), Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Waterbury, Jean Parker (editor), The Oldest City, (1983), St. Augustine Historical Society.

Images

- Freedom Trail [1] information about the civil rights movement in St. Augustine and the Freedom Trail that marks its sites.

- St. Augustine Pics Daily pictures of St. Augustine, Florida.

- Twine Collection Over 100 images of the St. Augustine community of Lincolnville between 1922 and 1927. From the State Library & Archives of Florida.

- St. Augustine Images Historic Images of St. Augustine An online archive of historical images of St. Augustine, including Flagler's hotels, the plaza, government building, sea wall, Fort, and more.

External links

Government resources

Local news media

- The St. Augustine Record/staugustine.com, owned by Morris Communications, is St. Augustine's only daily newspaper.

- Historic City News, daily online news journal

- St Augustine Community News, Open Residents participation type news portal

Historical

- Castillo de San Marcos official website, U.S. National Park Service

- St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum

- Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program (LAMP), maritime archaeology in St. Augustine

- History page (augustine.com)

- "St. Augustine Movement" in online King Encyclopedia (Stanford University)

- "St. Augustine Movement 1963-1964" at Civil Rights Movement Veterans website

Higher education