George Washington: Difference between revisions

Funandtrvl (talk | contribs) →External links: adj |

FkpCascais (talk | contribs) If you opose this edit please express your view at Wikipedia_talk:Manual_of_Style/Biographies#Country_of_birth.2C_for_historic_.28and_current.29_bios.2C_part_II as because of lack of participants this edit may become accepted |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

|successor5 = Office abolished |

|successor5 = Office abolished |

||

|birth_date = {{OldStyleDateDY|February 22,|1732|February 11, 1731}} |

|birth_date = {{OldStyleDateDY|February 22,|1732|February 11, 1731}} |

||

|birth_place = [[Westmoreland County, Virginia|Westmoreland]], [[ |

|birth_place = [[Westmoreland County, Virginia|Westmoreland]], [[United States]] |

||

|death_date = {{death date and age|1799|12|14|1732|2|22}} |

|death_date = {{death date and age|1799|12|14|1732|2|22}} |

||

|death_place = [[Mount Vernon, Virginia|Mount Vernon]], [[Virginia]], U.S. |

|death_place = [[Mount Vernon, Virginia|Mount Vernon]], [[Virginia]], U.S. |

||

Revision as of 02:47, 21 October 2011

George Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of the United States | |

| In office April 30, 1789* – March 4, 1797 | |

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | New creation |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Senior Officer of the Army | |

| In office July 13, 1798 – December 14, 1799 | |

| Appointed by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Hamilton |

| In office June 15, 1775 – December 23, 1783 | |

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Henry Knox |

| Delegate to the Second Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office May 10, 1775 – June 15, 1775 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Delegate to the First Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office September 5, 1774 – October 26, 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731] Westmoreland, United States |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouse | Martha Dandridge Custis |

| Profession | Planter Officer |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal Thanks of Congress |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Great Britain United States |

| Branch/service | Virginia Regiment Continental Army United States Army |

| Years of service | Militia: 1752–1758 Continental Army: 1775–1783 Army: 1798–1799 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Virginia Colony's regiment Continental Army United States Army |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War • Battle of Jumonville Glen • Battle of Fort Necessity • Braddock Expedition • Battle of the Monongahela • Forbes Expedition American Revolutionary War • Boston campaign • New York and New Jersey campaign • Philadelphia campaign • Yorktown campaign |

| |

George Washington (February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731] – December 14, 1799) was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of the Constitution in 1787. The unanimous choice to serve as the first President of the United States (1789–1797), Washington presided over the creation of a strong, well-financed national government that stayed neutral in the wars raging in Europe, suppressed rebellion and won acceptance among Americans of all types. His leadership style established many forms and rituals of government that have been used ever since, such as using a cabinet system and delivering an inaugural address. Washington is universally regarded as the "Father of his Country".

Washington was born into the provincial gentry of a wealthy, well connected Colonial Virginia family who owned tobacco plantations. After his father and older brother both died young, Washington became personally and professionally attached to the powerful Fairfax family, who promoted his career as a surveyor and soldier. Washington quickly became a senior officer of the colonial forces during the first stages of the French and Indian War. Chosen by the Second Continental Congress in 1775 to be commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in the American Revolution, he managed to force the British out of Boston in 1776, but was defeated and nearly captured later that year when he lost New York City. After crossing the Delaware River in the dead of winter, he defeated the enemy in two battles, retook New Jersey, and restored momentum to the Patriot cause. Because of his strategy, Revolutionary forces captured two major British armies at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. Historians give Washington high marks for: his selection and supervision of his generals; his encouragement of morale and ability to hold together the army; his coordination with the state governors and state militia units; his relations with Congress; and, his attention to supplies, logistics, and training. In battle, however, Washington was repeatedly outmaneuvered by British generals with larger armies. After victory had been finalized in 1783, Washington resigned rather than seize power, proving his opposition to dictatorship and his commitment to the emerging American political ideology of republicanism. He returned to his home, Mount Vernon, and his domestic life there, continuing to manage a variety of enterprises. Washington's final 1799 will specified all his slaves be set free.

Dissatisfied with the weaknesses of Articles of Confederation, Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention that drafted the United States Constitution in 1787. Elected as the first President of the United States in 1789, he attempted to bring rival factions together to unify the nation. He supported Alexander Hamilton's programs to pay off all state and national debt, to implement an effective tax system and to create a national bank (despite opposition from Thomas Jefferson). Washington proclaimed the U.S. neutral in the wars raging in Europe after 1793. He avoided war with Great Britain and guaranteed a decade of peace and profitable trade by securing the Jay Treaty in 1795, despite intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs. Washington's "Farewell Address" was an influential primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against partisanship, sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars.

Washington had a vision of a great and powerful nation that would be built on republican lines using federal power. He sought to use the national government to preserve liberty, improve infrastructure, open the western lands, promote commerce, found a permanent capital, reduce regional tensions and promote a spirit of American nationalism.[1] At his death, Washington was hailed as "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen".[2] The Federalists made him the symbol of their party but for many years the Jeffersonians continued to distrust his influence and delayed building the Washington Monument. As the leader of the first successful revolution against a colonial empire in world history, Washington became an international icon for liberation and nationalism, especially in France and Latin America.[3] He is consistently ranked among the top three presidents of the United States according to polls of both scholars and the general public.

Early life (1732–1753)

The first child of Augustine Washington (1694–1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), George Washington was born on their Pope's Creek Estate near present-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. According to the Julian calendar (which was in use at the time), Washington was born on February 11, 1731; according to the Gregorian calendar, implemented in 1752 according to the provisions of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, the date was February 22, 1732.[4][5][Note 1] Washington's ancestors were from Sulgrave, England; his great-grandfather, John Washington, had immigrated to Virginia in 1657.[6] George's father Augustine was a slave-owning tobacco planter who later tried his hand in iron-mining ventures.[7] In George's youth, the Washingtons were moderately prosperous members of the Virginia gentry, of "middling rank" rather than one of the leading families.[8]

Washington was the first-born child from his father's marriage to Mary Ball Washington. Six of his siblings reached maturity including two older half-brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, from his father's first marriage to Jane Butler Washington and four full-siblings, Samuel, Elizabeth (Betty), John Augustine and Charles. Three siblings died before becoming adults: his full-sister Mildred died when she was about one,[9] his half-brother Butler died while an infant[10] and his half-sister Jane died at the age of 12 when George was about 2.[9] George's father died when George was 11 years old, after which George's half-brother Lawrence became a surrogate father and role model. William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law and cousin of Virginia's largest landowner, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, was also a formative influence. Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County near Fredericksburg. Lawrence Washington inherited another family property from his father, a plantation on the Potomac River which he later named Mount Vernon. George inherited Ferry Farm upon his father's death, and eventually acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence's death.[11]

The death of his father prevented Washington from crossing the Atlantic to receive the rest of his education at England's Appleby School, as his older brothers had done. He received the equivalent of an elementary school education[12] from a variety of tutors and also at least one school (run by an Anglican clergyman in or near Fredericksburg).[13][14] Talk of securing an appointment in the Royal Navy for him when he was 15 was dropped when his mother learned how hard that would be on him.[15] Thanks to Lawrence's connection to the powerful Fairfax family, at age 17 Washington was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County in 1749, a well-paid position which enabled him to purchase land in the Shenandoah Valley, the first of his many land acquisitions in western Virginia. Thanks also to Lawrence's involvement in the Ohio Company, a land investment company funded by Virginia investors, and Lawrence's position as commander of the Virginia militia, Washington came to the notice of the new lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Washington was hard to miss: At exactly six feet, he towered over most of his contemporaries.[16]

In 1751, Washington travelled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was suffering from tuberculosis, with the hope that the climate would be beneficial to Lawrence's health. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred, but immunized him against future exposures to the dreaded disease.[17] Lawrence's health did not improve: he returned to Mount Vernon, where he died in 1752.[18] Lawrence's position as Adjutant General (militia leader) of Virginia was divided into four offices after his death. Washington was appointed by Governor Dinwiddie as one of the four district adjutants in February 1753, with the rank of major in the Virginia militia.[19] Washington also joined the Freemasons in Fredericksburg at this time.[20]

French and Indian War (or 'Seven Years War', 1754–1758)

In 1753, the French began expanding their military control into the "Ohio Country", a territory also claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a war in the colonies called the French and Indian War (1754–62), and contributed to the start of the global Seven Years' War (1756–63). Washington was at the center of its beginning. The Ohio Company was one vehicle through which British investors planned to expand into the territory, opening new settlements and building trading posts for the Indian trade. Governor Dinwiddie received orders from the British government to warn the French of British claims, and sent Major Washington in late 1753 to deliver a letter informing the French of those claims and asking them to leave.[21] Washington also met with Tanacharison (also called "Half-King") and other Iroquois leaders allied to Virginia at Logstown to secure their support in case of conflict with the French; Washington and Tanacharison became friends and allies. Washington delivered the letter to the local French commander, who politely refused to leave.[22]

Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio Country to protect an Ohio Company group building a fort at present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania but before he reached the area, a French force drove out the company's crew and began construction of Fort Duquesne. A small detachment of French troops led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville, was discovered by Tanacharison and a few warriors east of present-day Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Along with their Mingo allies, Washington and some of his militia unit then ambushed the French. What exactly happened during and after the battle is a matter of some controversy, but the immediate outcome was that Jumonville was injured in the initial attack and then was killed - whether tomahawked by Tanacharison in cold blood or somehow shot by another onlooker with a musket as the injured man sat with Washington is not completely clear.[23][24] The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754.[25] However, he was allowed to return with his troops to Virginia. Historian Joseph Ellis concludes that the episode demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience and impetuosity.[26] These events had international consequences; the French accused Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission.[26] Both France and Great Britain were ready to fight for control of the region and both sent troops to North America in 1755; war was formally declared in 1756.[27]

Braddock disaster 1755

In 1755, Washington was the senior American aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Braddock expedition. This was the largest British expedition to the colonies, and was intended to expel the French from the Ohio Country. The French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock, who was mortally wounded in the Battle of the Monongahela. After suffering devastating casualties, the British retreated in disarray; however, Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnants of the British and Virginian forces to an organized retreat.[28]

Commander of Virginia Regiment

Governor Dinwiddie rewarded Washington in 1755 with a commission as "Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Chief of all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty's Colony" and gave him the task of defending Virginia's frontier. The Virginia Regiment was the first full-time American military unit in the colonies (as opposed to part-time militias and the British regular units). Washington was ordered to "act defensively or offensively" as he thought best.[29] In command of a thousand soldiers, Washington was a disciplinarian who emphasized training. He led his men in brutal campaigns against the Indians in the west; in 10 months units of his regiment fought 20 battles, and lost a third of its men. Washington's strenuous efforts meant that Virginia's frontier population suffered less than that of other colonies; Ellis concludes "it was his only unqualified success" in the war.[30][31]

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly fire episode in which his unit and another British unit thought the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with 14 dead and 26 wounded in the mishap. Washington was not involved in any other major fighting on the expedition, and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley, when the French abandoned the fort. Following the expedition, Washington retired from his Virginia Regiment commission in December 1758. He did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.[32]

Lessons learned

Although Washington never gained the commission in the British army he yearned for, in these years the young man gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills.[33] He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He demonstrated his toughness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence—given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in battle, he appeared to soldiers to be a natural leader and they followed him without question.[34][35] Washington learned to organize, train, drill, and discipline his companies and regiments. From his observations, readings and conversations with professional officers, he learned the basics of battlefield tactics, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics.[36] He gained an understanding of overall strategy, especially in locating strategic geographical points.[37] Historian Ron Chernow is of the opinion that his frustrations in dealing with government officials during this conflict led him to advocate the advantages of a strong national government and a vigorous executive agency that could get results;[38] other historians tend to ascribe Washington's position on government to his later American Revolutionary War service.[Note 2] He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, too undisciplined, and too short-term compared to regulars.[39] On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of at most 1000 men, and came only in remote frontier conditions that were far removed from the urban situations he faced during the Revolution at Boston, New York, Trenton and Philadelphia.[40]

Between the wars: Mount Vernon (1759–1774)

On January 6, 1759, Washington married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis. Surviving letters suggest that he may have been in love at the time with Sally Fairfax, the wife of a friend.[41] Nevertheless, George and Martha made a compatible marriage, because Martha was intelligent, gracious, and experienced in managing a slave plantation.[42] Together the two raised her two children from her previous marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy" by the family. Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together – his earlier bout with smallpox in 1751 may have made him sterile.[43] Washington may not have been able to admit to his own sterility while privately he grieved over not having his own children.[44] The newlywed couple moved to Mount Vernon, near Alexandria, where he took up the life of a planter and political figure.[45]

Washington's marriage to Martha greatly increased his property holdings and social standing, and made him one of Virginia's wealthiest men. He acquired one-third of the 18,000-acre (73 km2) Custis estate upon his marriage, worth approximately $100,000, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children, for whom he sincerely cared.[46] He frequently bought additional land in his own name and was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres (26 km2), and had increased the slave population there to more than 100 persons. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.[47]

Washington lived an aristocratic lifestyle—fox hunting was a favorite leisure activity.[48] He also enjoyed going to dances and parties, in addition to the theater, races, and cockfights. Washington also was known to play cards, backgammon, and billiards.[49] Like most Virginia planters, he imported luxuries and other goods from England and paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop.[50]

Washington began to pull himself out of debt in the mid 1760s by diversifying his previously tobacco-centric business interests into other ventures[51] and paying more attention to his affairs.[52] In 1766, he started switching Mount Vernon's primary cash crop away from tobacco to wheat, a crop that could be processed and then sold in various forms in the colonies, and further diversified operations to include flour milling, fishing, horse breeding, spinning, weaving and (in the 1790s) whiskey production.[53] Patsy Custis's death in 1773 from epilepsy enabled Washington to pay off his British creditors, since half of her inheritance passed to him.[54]

A successful planter, he was a leader in the social elite in Virginia. From 1768 to 1775, he invited some 2000 guests to his Mount Vernon estate, mostly those he considered "people of rank". As for people not of high social status, his advice was to "treat them civilly" but "keep them at a proper distance, for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you sink in authority".[55] In 1769 he became more politically active, presenting the Virginia Assembly with legislation to ban the importation of goods from Great Britain.[56]

In 1754 Lieutenant Governor Dinwiddie had promised land bounties to the soldiers and officers who volunteered to serve during the French and Indian War.[57] Washington tried for years to get the lands promised to him and his men. Governor Norborne Berkeley finally fulfilled that promise in 1769–1770,[57][58] with Washington subsequently receiving title to 23,200 acres (94 km2) near where the Kanawha River flows into the Ohio River, in what is now western West Virginia.[59]

American Revolution (1775–1787)

Although he expressed opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the colonies, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance until protests of the Townshend Acts (enacted in 1767) became widespread. In May 1769, Washington introduced a proposal, drafted by his friend George Mason, calling for Virginia to boycott English goods until the Acts were repealed.[60] Parliament repealed the Townshend Acts in 1770. However, Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges".[61] In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves" were adopted, which called for the convening of a Continental Congress, among other things. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.[62]

Commander in chief

After the Battles of Lexington and Concord near Boston in April 1775, the colonies went to war. Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in a military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war.[63] Washington had the prestige, military experience, charisma and military bearing of a military leader and was known as a strong patriot. Virginia, the largest colony, deserved recognition, and New England—where the fighting began—realized it needed Southern support. Washington did not explicitly seek the office of commander and said that he was not equal to it, but there was no serious competition.[64] Congress created the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. Nominated by John Adams of Massachusetts, Washington was then appointed Major General and Commander-in-chief.[65]

Washington had three roles during the war. In 1775–77, and again in 1781 he led his men against the main British forces. Although he lost many of his battles, he never surrendered his army during the war, and he continued to fight the British relentlessly until the war's end. He plotted the overall strategy of the war, in cooperation with Congress.[66]

Second, he was charged with organizing and training the army. He recruited regulars and assigned General von Steuben, a German professional, to train them. The war effort and getting supplies to the troops were under the purview of Congress,[67] but Washington pressured the Congress to provide the essentials.[68] In June 1776 Congress' first attempt at running the war effort was established with the committee known as "Board of War and Ordnance", succeeded by the Board of War in July 1777, a committee which eventually included members of the military.[67] The command structure of the Americans' armed forces was a hodgepodge of Congressional appointees (and Congress sometimes made those appointments without Washington's input) with state-appointments filling the lower ranks and of all of the militia-officers.[69] The results of his general staff were mixed, as some of his favorites (like John Sullivan) never mastered the art of command. Eventually he found capable officers, like General Nathaniel Greene, and his chief-of-staff Alexander Hamilton. The American officers never equalled their opponents in tactics and maneuver, and consequently they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes, at Boston (1776), Saratoga (1777) and Yorktown (1781), came from trapping the British far from base with much larger numbers of troops.[66]

Third, and most important, Washington was the embodiment of armed resistance to the Crown—the representative man of the Revolution. His enormous stature and political skills kept Congress, the army, the French, the militias, and the states all pointed toward a common goal. By voluntarily stepping down and disbanding his army when the war was won, he permanently established the principle of civilian supremacy in military affairs. And yet his constant reiteration of the point that well-disciplined professional soldiers counted for twice as much as erratic amateurs helped overcome the ideological distrust of a standing army.[70]

Victory at Boston

Washington assumed command of the Continental Army in the field at Cambridge, Massachusetts in July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. American troops raided British arsenals, including some in the Caribbean, and some manufacturing was attempted. They obtained a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[71] Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston in March 1776 and Washington moved his army to New York City.[66]

Although highly disparaging toward most of the Patriots, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. These articles were bold, as Washington was an enemy general who commanded an army in a cause that many Britons believed would ruin the empire.[72]

Defeat at New York City and Fabian tactics

In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign designed to seize New York. The Continental Army under Washington engaged the enemy for the first time as an army of the newly independent United States at the Battle of Long Island, the largest battle of the entire war. The Americans were badly outnumbered, many men deserted, and Washington was badly beaten. Subsequently, Washington was forced to retreat across the East River at night. He did so without loss of life or materiel.[73] Washington retreated north from the city to avoid encirclement, enabling Howe to take the offensive and capture Fort Washington on November 16 with high Continental casualties. Washington then retreated across New Jersey; the future of the Continental Army was in doubt due to expiring enlistments and the string of losses.[74] On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a comeback with a surprise attack on a Hessian outpost in western New Jersey. He led his army across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up his victory at Trenton with another over British regulars at Princeton in early January. The British retreated back to New York City and its environs, which they held until the peace treaty of 1783. Washington's victories wrecked the British carrot-and-stick strategy of showing overwhelming force then offering generous terms. The Americans would not negotiate for anything short of independence.[75] These victories alone were not enough to ensure ultimate Patriot victory, however, since many soldiers did not reenlist or deserted during the harsh winter. Washington and Congress reorganized the army with increased rewards for staying and punishment for desertion, which raised troop numbers effectively for subsequent battles.[76]

Historians debate whether or not Washington preferred a Fabian strategy[77] to harass the British with quick, sharp attacks followed by a retreat so the larger British army could not catch him, or whether he preferred to fight major battles.[78] While his southern commander Greene in 1780-81 did use Fabian tactics, Washington, only did so in fall 1776 to spring 1777, after losing New York City and seeing much of his army melt away. Trenton and Princeton were Fabian examples. By summer 1777, however, Washington had rebuilt his strength and his confidence and stopped using raids and went for large-scale confrontations, as at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and Yorktown.[79]

1777 campaigns

In the late summer of 1777 the British under John Burgoyne sent a major invasion army south from Quebec, with the intention of splitting off rebellious New England. General Howe in New York took his army south to Philadelphia instead of going up the Hudson River to join with Burgoyne near Albany. It was a major strategic mistake for the British, and Washington rushed to Philadelphia to engage Howe, while closely following the action in upstate New York. In pitched battles that were too complex for his relatively inexperienced men, Washington was defeated. At the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, Howe outmaneuvered Washington, and marched into the American capital at Philadelphia unopposed on September 26. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October. Meanwhile, Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga, New York.[80] It was a major turning point militarily and diplomatically. France responded to Burgoyne's defeat by entering the war, openly allying with America and turning the Revolutionary War into a major worldwide war. Washington's loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing Washington from command. This attempt failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.[81]

Valley Forge

Washington's army of 11,000[82] went into winter quarters at Valley Forge north of Philadelphia in December 1777. Over the next six months, the deaths in camp numbered in the thousands (the majority being from disease),[83] with historians' death toll estimates ranging from 2000[83] to 2500[84][85] to over 3000 men.[86] The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff.[87] The British evacuated Philadelphia to New York in 1778,[88] shadowed by Washington. Washington attacked them at Monmouth, fighting to an effective draw in one of the war's largest battles.[89] Afterwards, the British continued to head towards New York, and Washington moved his army outside of New York.[88]

Victory at Yorktown

In the summer of 1779 at Washington's direction, General John Sullivan carried out a scorched earth campaign that destroyed at least 40 Iroquois villages in central and upstate New York; the Indians were British allies who had been raiding American settlements on the frontier.[90] In July 1780, 5,000 veteran French troops led by General Comte Donatien de Rochambeau arrived at Newport, Rhode Island to aid in the war effort.[91] The Continental Army having been funded by $20,000 in French gold, Washington delivered the final blow to the British in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781, marked the end of major fighting in continental North America.[92]

Demobilization

Washington could not know that after Yorktown the British would not reopen hostilities. They still had 26,000 troops occupying New York City, Charleston and Savannah, together with a powerful fleet. The French army and navy departed, so the Americans were on their own in 1782-83. The treasury was empty, and the unpaid soldiers were growing restive, almost to the point of mutiny or possible coup d'état. Washington dispelled unrest among officers by suppressing the Newburgh Conspiracy in March 1783, and Congress came up with the promise of a five years bonus.[93]

By the Treaty of Paris (signed that September), Great Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers.[94]

On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession. At Fraunces Tavern on December 4, Washington formally bade his officers farewell and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief. Historian Gordon Wood concludes that the greatest act in his life was his resignation as commander of the armies—an act that stunned aristocratic Europe.[95] King George III called Washington "the greatest character of the age" because of this.[96]

Constitutional Convention (1787)

Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He made an exploratory trip to the western frontier in 1784,[65] was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and was unanimously elected president of the Convention. He participated little in the debates (though he did vote for or against the various articles), but his high prestige maintained collegiality and kept the delegates at their labors. The delegates designed the presidency with Washington in mind, and allowed him to define the office once elected.[97] After the Convention, his support convinced many to vote for ratification; the new Constitution was ratified by all thirteen states.[98]

Presidency (1789–1797)

The Electoral College elected Washington unanimously as the first president in 1789,[Note 3] and again in the 1792 election; he remains the only president to have received 100 percent of the electoral votes.[Note 4] John Adams, who received the next highest vote total, was elected Vice President. At his inauguration, Washington took the oath of office as the first President of the United States of America on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City.[100]

The 1st United States Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however, he ultimately accepted the payment, to avoid setting a precedent whereby the presidency would be perceived as limited only to independently wealthy individuals who could serve without any salary.[101] The president, aware that everything he did set a precedent, attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested.[102]

Washington proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he talked regularly with department heads and listened to their advice before making a final decision.[103] In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."[104]

Washington reluctantly served a second term. He refused to run for a third, establishing the customary policy of a maximum of two terms for a president.[66]

Domestic issues

Washington was not a member of any political party and hoped that they would not be formed, fearing conflict that would undermine republicanism.[105] His closest advisors formed two factions, setting the framework for the future First Party System. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, and formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of the State Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Jeffersonian Republicans, strenuously opposed Hamilton's agenda, but Washington typically favored Hamilton over Jefferson, and it was Hamilton's agenda that went into effect.[106] Jefferson's political actions, and his attempt to undermine Hamilton, nearly led George Washington to dismiss Jefferson from his cabinet.[107] Though Jefferson left the cabinet voluntarily, Washington never forgave him, and never spoke to him again.[107]

The Residence Act of 1790, which Washington signed, authorized the President to select the specific location of the permanent seat of the government, which would be located along the Potomac River. The Act authorized the President to appoint three commissioners to survey and acquire property for this seat. Washington personally oversaw this effort throughout his term in office. In 1791, the commissioners named the permanent seat of government "The City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia" to honor Washington. In 1800, the Territory of Columbia became the District of Columbia when the federal government moved to the site according to the provisions of the Residence Act.[108]

In 1791, Congress imposed an excise tax on distilled spirits, which led to protests in frontier districts, especially Pennsylvania. By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale defiance of federal authority known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The federal army was too small to be used, so Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792 to summon militias from Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey.[109] The governors sent the troops and Washington took command, marching into the rebellious districts. The rebels dispersed and there was no fighting, as Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.[110]

Foreign affairs

In spring 1793 a major war broke out between conservative Great Britain and its allies and revolutionary France, launching an era of large-scale warfare that engulfed Europe until 1815. Washington, with cabinet approval, proclaimed American neutrality. The revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt was welcomed with great enthusiasm and propagandized the case for France in the French war against Great Britain, and for this purpose promoted a network of new Democratic Societies in major cities. He issued French letters of marque and reprisal to French ships manned by American sailors so they could capture British merchant ships. Washington, warning and mistrustful of the influence of Illuminism that had been so strong in the French Revolution (as recounted by John Robison and Abbé Augustin Barruel) and its Reign of Terror, demanded the French government recall Genêt, and denounced the societies.[111]

Hamilton and Washington designed the Jay Treaty to normalize trade relations with Great Britain, remove them from western forts, and resolve financial debts left over from the Revolution.[112] John Jay negotiated and signed the treaty on November 19, 1794. The Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington's strong support mobilized public opinion and proved decisive in securing ratification in the Senate by the necessary two-thirds majority.[113] The British agreed to depart from their forts around the Great Lakes, subsequently the U.S.-Canadian boundary had to be re-adjusted, numerous pre-Revolutionary debts were liquidated, and the British opened their West Indies colonies to American trade. Most importantly, the treaty delayed war with Great Britain and instead brought a decade of prosperous trade with Great Britain. The treaty angered the French and became a central issue in many political debates.[114] Relations with France deteriorated after the treaty was signed, leaving his successor, John Adams, with the prospect of war.[115][116]

Farewell Address

Washington's Farewell Address (issued as a public letter in 1796) was one of the most influential statements of republicanism. Drafted primarily by Washington himself, with help from Hamilton, it gives advice on the necessity and importance of national union, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law, the evils of political parties, and the proper virtues of a republican people. He called morality "a necessary spring of popular government". He said, "Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle."[117]

Washington's public political address warned against foreign influence in domestic affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warned against bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He warned against "permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world",[118] saying the United States must concentrate primarily on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term "entangling" alliances. The address quickly set American values regarding foreign affairs.[119]

Retirement (1797–1799)

After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He devoted much time to farming and other business interests, including his distillery which produced its first batch of spirits in February 1797.[120] As Chernow (2010) explains, his farm operations were at best marginally profitable. The lands out west yielded little income because they were under attack by Indians and the squatters living there refused to pay him rents. However most Americans assumed he was truly rich because of the well-known "glorified façade of wealth and grandeur" at Mount Vernon.[121] Historians estimate his estate was worth about $1 million in 1799 dollars, equivalent to about $18 million in 2009 purchasing power.[122]

By 1798 relations with France had deteriorated to the point that war seemed imminent, and on July 4, 1798, President Adams offered Washington a commission as lieutenant general and Commander-in-chief of the armies raised or to be raised for service in a prospective war. He reluctantly accepted, and served as the senior officer of the United States Army between July 13, 1798, and December 14, 1799. He participated in the planning for a Provisional Army to meet any emergency that might arise, but avoided involvement in details as much as possible, delegating most of the work, including leadership of the army, to Hamilton.[123][124]

Death

On Thursday December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his farms on horseback, in snow, hail and freezing rain — later that evening eating his supper without changing from his wet clothes. Friday morning, he awoke with a severe sore throat (either quinsy or acute epiglottitis) and became increasingly hoarse as the day progressed. Sometime around 3 am that Saturday morning, he awoke his wife and said he felt ill. Following common medical practice at the time, he was bled; initially by an employee and later again by physicians. "A vein was opened, but no relief afforded. Couriers were dispatched to Dr. Craik, the family, and Drs. Dick and Brown, the consulting physicians, all of whom came with speed. The proper remedies were administered, but without producing their healing effects; while the patient, yielding to the anxious looks of all around him, waived his usual objections to medicines, and took those which were prescribed without hesitation or remark."[125] Washington died at home around 10 pm on Saturday December 14, 1799, aged 67. The last words in his diary were "'Tis well."[Note 5][126][127]

Throughout the world, men and women were saddened by Washington's death. Napoleon ordered ten days of mourning throughout France; in the United States, thousands wore mourning clothes for months.[128] To protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only a total of five letters between the couple are known to have survived, two letters from Martha to George and three from George to Martha.[129][130]

On December 18, 1799, a funeral was held at Mount Vernon, where his body was interred.[131] Congress passed a joint resolution to construct a marble monument in the United States Capitol for his body, supported by Martha. In December 1800, the United States House passed an appropriations bill for $200,000 to build the mausoleum, which was to be a pyramid that had a base 100 feet (30 m) square. Southern opposition to the plan defeated the measure because they felt it was best to have his body remain at Mount Vernon.[132]

In 1831, for the centennial of his birth, a new tomb was constructed to receive his remains. That year, an attempt was made to steal the body of Washington, but proved to be unsuccessful.[133] Despite this, a joint Congressional committee in early 1832 debated the removal of Washington's body from Mount Vernon to a crypt in the Capitol, built by Charles Bulfinch in the 1820s. Yet again, Southern opposition proved very intense, antagonized by an ever-growing rift between North and South. Congressman Wiley Thompson of Georgia expressed the fear of Southerners when he said:

Remove the remains of our venerated Washington from their association with the remains of his consort and his ancestors, from Mount Vernon and from his native State, and deposit them in this capitol, and then let a severance of the Union occur, and behold the remains of Washington on a shore foreign to his native soil.[134]

This ended any talk of the movement of his remains, and he was moved to the new tomb that was constructed there on October 7, 1837, presented by John Struthers of Philadelphia.[135] After the ceremony, the inner vault's door was closed and the key was thrown into the Potomac.[136]

Legacy

Congressman Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, a Revolutionary War comrade, famously eulogized Washington:[137]

First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen, he was second to none in humble and enduring scenes of private life. Pious, just, humane, temperate, and sincere; uniform, dignified, and commanding; his example was as edifying to all around him as were the effects of that example lasting...Correct throughout, vice shuddered in his presence and virtue always felt his fostering hand. The purity of his private character gave effulgence to his public virtues...Such was the man for whom our nation mourns.

Lee's words set the standard by which Washington's overwhelming reputation was impressed upon the American memory. Washington set many precedents for the national government, and the presidency in particular, and was called the "Father of His Country" as early as 1778.[Note 6][138][139][140] Washington's Birthday (celebrated on Presidents' Day), is a federal holiday in the United States.[141]

During the United States Bicentennial year, George Washington was posthumously appointed to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by the congressional joint resolution Public Law 94-479 passed on January 19, 1976, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1976.[65] This restored Washington's position as the highest-ranking military officer in U.S. history.[Note 7]

Cherry tree

Apocryphal stories about Washington's childhood include a claim that he skipped a silver dollar across the Potomac River at Mount Vernon, and that he chopped down his father's cherry tree and admitted the deed when questioned: "I can't tell a lie, Pa." The anecdote was first reported by biographer Parson Weems, who after Washington's death interviewed people who knew him as a child. The Weems version was very widely reprinted throughout the 19th century, for example in McGuffey Readers. Moralistic adults wanted children to learn moral lessons from the past from history, especially as taught by great national heroes like Washington. After 1890 however, historians insisted on scientific research methods to validate every story, and there was no evidence for this anecdote apart from Weems' report. Joseph Rodman in 1904 noted that Weems plagiarized other Washington tales from published fiction set in England. No one has found an alternative source for the cherry tree story, thus Weems' credibility is questioned.[142][143]

Monuments and memorials

Starting with victory in their Revolution, there were many proposals to build a monument to Washington. After his death, Congress authorized a suitable memorial in the national capital, but the decision was reversed when the Republicans took control of Congress in 1801. The Republicans were dismayed that Washington had become the symbol of the Federalist Party; furthermore, the values of Republicanism seemed hostile to the idea of building monuments to powerful men.[144] Further political squabbling, along with the North-South division on the Civil War, blocked the completion of the Washington Monument until the late 19th century. By that time, Washington had the image of a national hero who could be celebrated by both North and South, and memorials to him were no longer controversial.[145] Predating the obelisk on the National Mall by several decades, the first public memorial to Washington was built by the citizens of Boonsboro, Maryland, in 1827.[146]

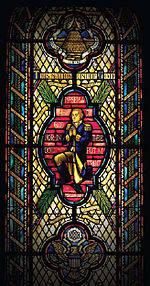

Today, Washington's face and image are often used as national symbols of the United States.[147] He appears on contemporary currency, including the one-dollar bill and the quarter coin, and on U.S. postage stamps. Along with appearing on the first postage stamps issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1847,[148] Washington, together with Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, and Lincoln, is depicted in stone at the Mount Rushmore Memorial. The Washington Monument, one of the most well known American landmarks, was built in his honor. The George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia, was constructed between 1922 and 1932 with voluntary contributions from all 52 local governing bodies of the Freemasons in the United States.[149][150]

Many places and entities have been named in honor of Washington. Washington's name became that of the nation's capital, Washington, D.C., one of two national capitals across the globe to be named after an American president (the other is Monrovia, Liberia). The state of Washington is the only state to be named after a United States President.[151] George Washington University and Washington University in St. Louis were named for him, as was Washington and Lee University (once Washington Academy), which was renamed due to Washington's large endowment in 1796. Washington College in Chestertown, Maryland (established by Maryland state charter in 1782) was supported by Washington during his lifetime with a 50 guineas pledge[152] and with service on the college's Board of Visitors and Governors until 1789 (when Washington was elected President).[153] According to the 1993 US Census, Washington is the 17th most common street name in the United States[154] and the only person's name so honored. [Note 8]

The Confederate Seal prominently featured George Washington on horseback,[155] in the same position as a statue of him in Richmond, Virginia.[156]

London hosts a standing statue of Washington, one of 22 bronze identical replicas. Based on Jean-Antoine Houdon's original marble statue in the Rotunda of the State Capitol in Richmond, Virginia, the duplicate was given to the British in 1921 by the Commonwealth of Virginia. It stands in front of the National Gallery at Trafalgar Square.[157]

In space, asteroid 886 Washingtonia is named in his honor.

Papers

The serious collection and publication of Washington's documentary record began with the pioneer work of Jared Sparks in the 1830s, Life and Writings of George Washington (12 vols., 1834–1837). The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799 (1931–44) is a 37 volume set edited by John C. Fitzpatrick. It contains over 17,000 letters and documents and is available online from the University of Virginia.[158]

The definitive letterpress edition of his writings was begun by the University of Virginia in 1968, and today comprises 52 published volumes, with more to come. It contains everything written by Washington, or signed by him, together with most of his incoming letters. Part of the collection is available online from the University of Virginia.[159]

Personal life

Along with Martha's biological family noted above, George Washington had a close relationship with his nephew and heir Bushrod Washington, son of George's younger brother John Augustine Washington. After his uncle's death, Bushrod became an Associate Justice on the US Supreme Court. George's relationship with his mother, Mary Ball Washington, however, was apparently somewhat difficult and strained.[160]

As a young man, Washington had red hair.[161][162] A popular myth is that he wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. Washington did not wear a wig; instead, he powdered his hair,[163][164] as represented in several portraits, including the well-known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.[165]

Washington had unusually great physical strength that amazed younger men. While the story of him throwing a silver dollar across the Potomac River is untrue, he did throw a rock to the top of the 215 feet-tall Natural Bridge. Jefferson called Washington "the best horseman of his age", and both American and European observers praised his riding; the horsemanship benefited his hunting, a favorite hobby. Washington was an excellent dancer and frequently attended the theater, often referencing Shakespeare in letters.[166] He drank in moderation and precisely recorded gambling wins and losses, but Washington disliked the excessive drinking, gambling, smoking, and profanity that was common in colonial Virginia. Although he grew tobacco he eventually stopped smoking, and considered drunkenness a man's worst vice; Washington was glad that post-Revolutionary Virginia society was less likely to "force [guests] to drink and to make it an honor to send them home drunk."[167]

Washington suffered from problems with his teeth throughout his life. He lost his first adult tooth when he was twenty-two and had only one left by the time he became President.[168] John Adams claims he lost them because he used them to crack Brazil nuts but modern historians suggest the mercury oxide, which he was given to treat illnesses such as smallpox and malaria, probably contributed to the loss. He had several sets of false teeth made, four of them by a dentist named John Greenwood.[168] Contrary to popular belief, none of the sets were made from wood. The set made when he became President was carved from hippopotamus and elephant ivory, held together with gold springs.[169] The hippo ivory was used for the plate, into which human teeth (quite possibly from slaves)[170] and bits of horses' and donkeys' teeth were inserted. Dental problems left Washington in constant pain, for which he took laudanum.[171] This distress may be apparent in many of the portraits painted while he was still in office,[171] including the one still used on the $1 bill.[165][Note 9]

Slavery

Regarding slavery, Washington is best known for setting the example of freeing his slaves in his 1799 will, to take effect on the death of his widow. His will provided for training the younger slaves in useful skills, and created a fund for old age pensions for the older ones.[172]

On the death of his father in 1743, the 11-year-old inherited 10 slaves. At the time of his marriage to Martha Custis in 1759, he personally owned at least 36 (and the widow's third of her first husband's estate brought at least 85 "dower slaves" to Mount Vernon). Using his wife's great wealth he bought land, tripling the size of the plantation, and additional slaves to farm it. By 1774, he paid taxes on 135 slaves (this does not include the "dowers"). The last record of a slave purchase by him was in 1772, although he later received some slaves in repayment of debts.[173] Washington also used some hired staff[174] and white indentured servants; in April 1775, he offered a reward for the return of two runaway white servants.[175]

One historian claims that Washington desired the material benefits from owning slaves and wanted to give his wife's family a wealthy inheritance.[176] Before the American Revolution, Washington expressed no moral reservations about slavery, but in 1786, Washington wrote to Robert Morris, saying, "There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery."[177] In 1779, he told his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished to sell his slaves when the war ended, if it ended in an American victory.[178] Maintaining a large, and increasingly elderly, slave population at Mount Vernon was not economically profitable. Washington could not legally sell the "dower slaves," however, and because these slaves had long intermarried with his own slaves, he could not sell his slaves without breaking up families.[179]

As president, Washington brought seven slaves to New York City in 1789 to work in the first presidential household. Following the transfer of the national capital to Philadelphia in 1790, he brought nine slaves to work in the President's House. At the time of his death, there were 317 slaves at Mount Vernon– 123 owned by Washington, 154 "dower slaves," and 40 rented from a neighbor.[180] Dorothy Twohig argues that Washington did not speak out publicly against slavery, because he did not wish to create a split in the new republic, with an issue that was sensitive and divisive.[181]

By 1794 as he contemplated retirement Washington began organizing his affairs so that he could free all the slaves he owned outright in his will.[182] He did so. His will provided they be freed when Martha died, but she freed them 12 months after his death. Chernow says, "By freeing his slaves Washington accomplished....what no other founding father dared to do. He brought the American experience that much closer to the ideals of the American revolution."[183]

Religion

Washington was an outspoken leader in calling for religious liberty and tolerance, and used his prestige as general and president to promote good will among Protestants, Catholics, and Jews. He sought to create a national ethos that would enable every American to, in his paraphrase of the Book of Micah,[184] "sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree and there shall be none to make him afraid." In private and in public he strongly rejected any sign of intolerance, prejudice, and "every species of religious persecution", while hoping that "bigotry and superstition" would be overcome by "truth and reason" in the United States.[185]

In Virginia, Washington was a member of the Anglican Church,[186] which had 'established status' (meaning tax money was used to pay its minister). As a leading land owner he served on the vestry (governing board) for Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia and for Pohick Church near his Mount Vernon home until the war began. The parish was the unit of local government and the vestry dealt mostly with civic affairs such as roads and poor relief.[187]

According to historian Paul F. Boller Jr., "Washington was in fact a typical 18th-century deist."[188][189] Boller finds that "Washington seems to have had the characteristic unconcern of the eighteenth-century Deist for the forms and creeds of institutional religion. He had, moreover, the strong aversion of the upper-class Deist for sectarian quarrels that threatened to upset the 'peace of Society'."[190] Washington never made attempts to personalize his own religious views or express any appeal to the aesthetic side of biblical passages. Boller states that Washington's "allusions to religion are almost totally lacking in depths of feeling."[191] In philosophical terms, he admired and adopted the Stoic philosophy of the ancient Romans, which emphasized virtue and humanitarianism and was highly compatible with Deism.[192] Historian Patrick Allitt characterized Washington's religious views as "lukewarm", and said "he went through the motions but he clearly wasn't a man of particular piety or devotion."[186]

In a letter to George Mason in 1785, Washington wrote that he was not among those alarmed by a bill "making people pay towards the support of that [religion] which they profess," but felt that it was "impolitic" to pass such a measure, and wished it had never been proposed, believing that it would disturb public tranquility.[193]

Washington frequently accompanied his wife to church services. Although there are third-hand reports that he took communion,[194] he is usually characterized as never or rarely participating in the rite.[195] He would regularly leave services before communion with the other non-communicants (as was the custom of the day), until, after being admonished by a rector, he ceased attending at all on communion Sundays.[196] As president he made a point of being seen attending services at numerous churches, including Presbyterian, Quaker, Congregational and Catholic. As president he officially saluted 22 religious groups and proclaimed his general support for religion.[197] Washington was known for his generosity. Highly gregarious, he attended many charity events and donated money to colleges, schools and to the poor. As Philadelphia's leading citizen, President Washington took the lead in providing charity to widows and orphans hit by the yellow fever epidemic that devastated the capital city in 1793.[198]

Freemasonry

Washington was initiated into Freemasonry in 1752.[199] Washington had a high regard for the Masonic Order and often praised it, but he seldom attended lodge meetings. He was attracted by the movement's dedication to Enlightenment principles of rationality, reason and fraternalism; the American lodges did not share the anti-clerical perspective that made the European lodges so controversial.[200]

Postage and currency

Since 1847 one of the defining hallmarks of a U.S. President is his appearance on U.S. currency and postage. George Washington appears on contemporary U.S. currency, including the one-dollar bill and the US quarter dollar. On U.S. postage stamps however, Washington appears numerous times more than all other presidents combined. [148]

|

|

|

|

See also

- 1932 Washington Bicentennial

- Historical rankings of Presidents of the United States

- List of federal judges appointed by George Washington

- List of Presidents of the United States, sortable by previous experience

- Old Style and New Style dates

- Town Destroyer, a nickname given to Washington by the Iroquois

- Washington Monument State Park

- US Presidents on US postage stamps

Notes

- ^ Contemporary records, which used the Julian calendar, recorded his birth as February 11, 1731. The provisions of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, implemented in 1752, altered the official British dating method to the Gregorian calendar with the start of the year on January 1 (it had been March 25). These changes resulted in dates being moved forward 11 days, and for those between January 1 and March 25, an advance of one year. For a further explanation of 'Old Style' (Julian) / 'New Style' (Gregorian) see Ancestry Magazine's Time to Take Note: The 1752 Calendar Change and for an explanation of how historians render Washington's birthdate and year see Ancestry's When is George Washington's Birthday?

- ^ Ellis and Ferling, for example, do not discuss this stance in reference to Washington's French and Indian War service, and cast it almost exclusively in terms of his negative experiences dealing with the Continental Congress during the Revolution. See Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 218, Ferling, The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon (2010), pp. 32–33,200,258–272,316. Don Higginbotham places Washington's first formal advocacy of a strong central government in 1783 (Higginbotham, George Washington: Uniting a Nation (2004), p. 37).

- ^ Under the Articles of Confederation, Congress called its presiding officer "President of the United States in Congress Assembled". That person had no executive powers, but the similarity of titles has confused some into thinking there were other presidents before Washington.[99]

- ^ Under the system in place at the time, each elector cast two votes, with the winner becoming president and the runner-up vice president. All electors in the elections of 1789 and 1792 cast one of their votes for Washington; thus it may be said that he was elected president unanimously.

- ^ At least three modern medical authors (Wallenborn 1997, Shapiro 1975, Scheidemandel 1976) have concluded that Washington most probably died from acute bacterial epiglottitis complicated by the treatments given (all of which were accepted medical practice of that era). See Vadakan's Footnotes to A Physician Looks at the Death of Washington for these references, also his article's quotation of Doctors James Craik and Elisha C. Dick's account in the Times of Alexandria(newspaper) of what happened during their treatment of Washington. These treatments included multiple doses of calomel as well as performing extensive bloodletting, with a total of 3.75 liters of blood taken and the massive deliberate blood-loss contributing to the additional serious complication of shock.

- ^ The earliest known image in which Washington is identified as the Father of (His/Our/the) Country is in the frontispiece of a 1779 German-language almanac. With calculations by David Rittenhouse and published by Francis Bailey in Lancaster County Pennsylvania, Der Gantz Neue Nord-Americanishe Calendar has Fame appearing with an image of Washington, holding a trumpet to her lips from which the words "Der Landes Vater" (translated as "the father of the country" or "the father of the land") comes forth.

- ^ William Gardner Bell, in Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff 1775-2005 (written for the US Army Center of Military History), states that when Washington was recalled back into military service from his retirement in 1798, "Congress passed legislation that would have made him General of the Armies of the United States, but his services were not required in the field and the appointment was not made until the Bicentennial in 1976, when it was bestowed posthumously as a commemorative honor." How many U.S. Army five-star generals have there been and who were they? states that with Public Law 94-479 President Ford specified that Washington would "rank first among all officers of the Army, past and present. "General of the Armies of the United States" is only associated with two people...one being Washington and the other being John J. Pershing, the complete history of the rank can be found at the US Army Center for Military History's webpage on How many U.S. Army five-star generals have there been and who were they?

- ^ The rest of the Top 20 street names are all descriptive (Hill, View and so on), arboreal (Pine, Maple, etc.) or numeric (Second, Third, etc.).

- ^ The Smithsonian Institution states in "The Portrait — George Washington: A National Treasure" that:

- Stuart admired the sculpture of Washington by French artist Jean-Antoine Houdon, probably because it was based on a life mask and therefore extremely accurate. Stuart explained, "When I painted him, he had just had a set of false teeth inserted, which accounts for the constrained expression so noticeable about the mouth and lower part of the face. Houdon's bust does not suffer from this defect. I wanted him as he looked at that time." Stuart preferred the Athenaeum pose and, except for the gaze, used the same pose for the Lansdowne painting.[171]

References

- ^ Cayton, Andrew (September 30, 2010). "Learning to Be Washington". New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ Conor Cruise O'Brien. First in Peace: How George Washington Set the Course for America (2009) p. 19

- ^ Marcus Cunliffe, George Washington: Man and Monument (1958) pp. 24-26

- ^ Engber, Daniel (January 18, 2006). "What's Benjamin Franklin's Birthday?". Slate. Retrieved May 21, 2011. (Both Franklin's and Washington's confusing birth dates are clearly explained.)

- ^ "Image of page from family Bible". Papers of George Washington. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ Randall, George Washington: A Life (1998), pp. 8,11

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 8

- ^ Twohig, Dorothy (1998). Hofstra, Warren R (ed.). "The Making of George Washington". George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry. Madison, WI: Madison House. ISBN 9780945612506.

- ^ a b "George Washington's Family Chart". Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ "Burials at George Washington Birthplace National Monument". George Washington Birthplace National Monument. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 23, 2008. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (1948), pp. 1:15–72

- ^ "American President:George Washington (1732-1799)". Miller Center (University of Virginia). Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ John E. Ferling (2010). The First of Men: A Life of George Washington. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9780195398670. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ "A Brief Biography of George Washington (Childhood: 1732-1746)". Mount Vernon. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (1948), p. 1:199

- ^ Chernow, Washington: A Life (2010), pp. 53.

- ^ Flexner, Washington: The Indispensable Man (1976), p. 8

- ^ Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (1948), p. 1:264

- ^ Freeman, George Washington: A Biography (1948), p. 1:268

- ^ Randall, George Washington: A Life (1998), p. 67

- ^ Freeman, George Washington (1948), pp. 1:274–327

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington (2005) pp 23–24

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington (2005) pp 31–38

- ^ Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America (2000), pp. 53-58

- ^ Grizzard, George Washington pp 115–19

- ^ a b Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), pp. 17–18

- ^ Anderson, The War That Made America (2005), pp. 100–101

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 22

- ^ Flexner, George Washington: the Forge of Experience, 1732–1775 (1965), p. 138

- ^ Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2004), pp. 15–16

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 38

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington pp 75–76, 81

- ^ Chernow, Washington: A Life (2010), ch. 8; Freeman and Harwell, Washington (1968), pp. 135–139; Flexner, Washington: The Indispensible Man (1984), pp. 32–36; Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), ch. 1; Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (1985), ch. 1; Lengel, General George Washington pp 77–80

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), pp. 38, 69

- ^ Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2004), p. 13

- ^ Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (1985), pp. 14–15

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington, p 80

- ^ Chernow, Washington: A Life (2010), ch. 8

- ^ Higginbotham, George Washington and the American Military Tradition (2004), pp. 22–25

- ^ Freeman and Harwell, Washington (1968), pp. 136–137

- ^ Ferling (2000), Setting the World Ablaze, p. 34

- ^ Ferling (2000), Setting the World Ablaze, pp. 33-34

- ^ Chernow, p. 103

- ^ Bumgarner, John R. (1994). The Health of the Presidents: The 41 United States Presidents Through 1993 from a Physician's Point of View. Jefferson, NC: MacFarland & Company. pp. 1–8.Flexner, James Thomas (1974). Washington: The Indispensible Man. Boston. Little, Brown. pp. 42, 43.

- ^ The Reader's Companion to American History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991. s.v. "Washington, George", credoreference.com (accessed 2011-06-02).

- ^ "George Washington 1732-99". Burke's Peerage and Gentry. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency, George Washington, pp. 41–42, 48

- ^ Ferling (2000), Setting the World Ablaze, p. 44

- ^ Ferling (2000), Setting the World Ablaze, pp. 43–44

- ^ Dennis J Pogue (2004). "Shad, Wheat, and Rye (Whiskey): George Washington, Entrepreneur" (PDF). Mount Vernon Ladies' Association(MountVernon.Org). p. 2. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Dennis J Pogue (2004). "Shad, Wheat, and Rye (Whiskey): George Washington, Entrepreneur" (PDF). Mount Vernon Ladies' Association(MountVernon.Org). pp. 2–4. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- ^ Dennis J. Pogue, PhD (Spring/Summer 2003). "George Washington And The Politics of Slavery" (PDF). Historic Alexandria Quarterly. Office of Historic Alexandria (Virginia). Retrieved 2011-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pogue, Shad, Wheat, and Rye Whiskey pp 2-10

- ^ Fox hunting: Ellis, p. 44. Mount Vernon economy: John Ferling, The First of Men, pp. 66–67; Ellis, pp. 50–53; Bruce A. Ragsdale, "George Washington, the British Tobacco Trade, and Economic Opportunity in Pre-Revolutionary Virginia", in Don Higginbotham, ed., George Washington Reconsidered, pp. 67–93.

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2004) p. 14

- ^ Ferling (2000), Setting the World Ablaze, pp. 73–76

- ^ a b Rasmussen, William Meade Stith (1999). George Washington--the man behind the myths. University of Virginia Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780813919003. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "George Washington:Surveyor and Mapmaker (Washington as land speculator — Western Lands and the Bounty of War)". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- ^ Grizzard, George Washington pp 135–37

- ^ Freeman, George Washington (1968) pp 174-76

- ^ Willard Sterne Randall, George Washington: A Life (1998) p. 262

- ^ Ferling, p. 99

- ^ Rasmussen, William Meade Stith (1999). George Washington—the man behind the myths. University of Virginia Press. p. 294. ISBN 9780813919003. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ellis, His Excellency pp 68–72

- ^ a b c Bell, William Gardner (1983). Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff: 1775–2005; Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the United States Army's Senior Officer. Center of Military History – United States Army. pp. 52, 66. ISBN 0160723760. CMH Pub 70–14. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Chambers Biographical Dictionary. London: Chambers Harrap, 2007. s.v. "Washington, George," http://www.credoreference.com/entry/chambbd/washington_george (accessed 2011-06-02).

- ^ a b "Creation of the War Department". Papers of the War Department, 1784-1800. January 20, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ E. Wayne Carp (1984). To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture, 1775–1783. p. 220. ISBN 9780807842690. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Philander Chase (2011). "George Washington". World Book Advanced. World Book Encyclopedia.

- ^ Jensen, Richard (February 12, 2002). "Military History of the American Revolution". UIC.edu. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ^ Orlando W. Stephenson, "The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776", American Historical Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (January 1925), pp. 271–281 in JSTOR

- ^ Troy O. Bickham, "Sympathizing with Sedition? George Washington, the British Press, and British Attitudes During the American War of Independence", William and Mary Quarterly 2002 59(1): 101–122. ISSN 0043-5597 Fulltext online in History Cooperative

- ^ McCullough, David (2005). 1776. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 186–195. ISBN 978-0743226714.

- ^ Ketchum, p.235

- ^ Fischer, Washington's Crossing p 367

- ^ George Washington Biography, American-Presidents.com. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ The term comes from the Roman strategy used by General Fabius against Hannibal's invasion in the Second Punic War.

- ^ Ferling and Ellis argue that Washington favored Fabian tactics and Higginbotham denies it. Ferling, First of Men; Ellis, His Excellency p 11; Higginbotham, "War of American Independence"

- ^ John Buchanan, The Road to Valley Forge: How Washington Built the Army That Won the Revolution (2004) p. 226

- ^ Don Higginbotham, The War of American Independence (Macmillan, 1971) ch 8

- ^ Bruce Heydt, "'Vexatious Evils': George Washington and the Conway Cabal", American History, Dec 2005, Vol. 40 Issue 5, pp 50-73, online at EBSCO

- ^ Chai, Jane (2009). "The Forging of an Army". Pennsylvania Center for the Book(Penn State). Retrieved January 19, 2011.