Germanic languages: Difference between revisions

corrected lexical error |

m lexical addition |

||

| Line 298: | Line 298: | ||

|that || that || dat || daardie / dit || dat / die || dat / tot || dat / dit || dat / dij || dat || das || þata || það || tað || det || det || det || det |

|that || that || dat || daardie / dit || dat / die || dat / tot || dat / dit || dat / dij || dat || das || þata || það || tað || det || det || det || det |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|two / twain || twa || twa || twee || twee || twie || twee || twij / twèje || zoo / zwou / zwéin || zwei/zwo || twái || tveir / tvær / tvö || tveir / tvey / tvær / tvá || två || to || to || to<ref>Dialectally tvo / två / tvei (m) / tvæ (f) / tvau (n).</ref> |

|two / twain || twa || twa || twee || twee || twie || twee || twij / twèje || zoo / zwou / zwéin || zwei/zwo || twái || tveir / tvær / tvö || tveir / tvey / tvær / tvá || två / tu || to || to || to<ref>Dialectally tvo / två / tvei (m) / tvæ (f) / tvau (n).</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|who || wha || wa || wie || wie || wee || wokeen || wel || wien || wer || Ƕas / hwas || hver || hvør || vem || hvem || hvem || kven |

|who || wha || wa || wie || wie || wee || wokeen || wel || wien || wer || Ƕas / hwas || hver || hvør || vem || hvem || hvem || kven |

||

Revision as of 22:28, 12 March 2012

| Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | In northern, western and central Europe, Anglo-America, Oceania, southern Africa |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Germanic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | gem |

| Linguasphere | 52- (phylozone) |

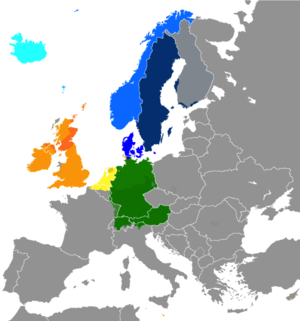

Countries where a Germanic language is the first language of the majority of the population

Countries where a Germanic language is an official but not primary language | |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Germanic languages constitute a sub-branch of the Indo-European (IE) language family. The common ancestor of all of the languages in this branch is called Proto-Germanic (also known as Common Germanic), which was spoken in approximately the mid-1st millennium BC in Iron Age northern Europe. Proto-Germanic, along with all of its descendants, is characterized by a number of unique linguistic features, most famously the consonant change known as Grimm's law. Early varieties of Germanic enter history with the Germanic peoples moving south from northern Europe in the 2nd century BC, to settle in north-central Europe.

The most widely spoken Germanic languages are English and German, with approximately 300–400 million[1][2] and over 100 million[3] native speakers respectively. They belong to the West Germanic family. The West Germanic group also includes other major languages, such as Dutch with 23 million[4] and Afrikaans with over 6 million native speakers;[5]. The North Germanic languages include Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, Icelandic, and Faroese with a combined total of about 20 million speakers.[6] The SIL Ethnologue lists 53 different Germanic languages.

Characteristics

Germanic languages possess several unique features, such as the following:

- Large number of vowels. Germanic languages, along with Wu Chinese dialects, have the largest vowel quality inventories in the world. Standard Swedish, for example, has at least 16 vowel qualities.[7]

- The leveling of the Indo-European verbal system of tense and aspect into the present tense and the past tense (also called the preterite)

- A large class of verbs that use a dental suffix (/d/ or /t/) instead of vowel alternation (Indo-European ablaut) to indicate past tense; these are called the Germanic weak verbs; the remaining verbs with vowel ablaut are the Germanic strong verbs

- The use of so-called strong and weak adjectives: different sets of inflectional endings for adjectives depending on the definiteness of the noun phrase (modern English adjectives do not inflect at all, except for the comparative and superlative; this was not the case in Old English, where adjectives were inflected differently depending on the type of their preceding determiner)

- The consonant shift known as Grimm's Law (which continued in German in a second shift known as the High German consonant shift)

- Some words with etymologies that are difficult to link to other Indo-European families but with variants that appear in almost all Germanic languages; see Germanic substrate hypothesis

- The sound change known as Verner's Law, which left a trace of Indo-European accent variations in voicing variations in fricatives

- The shifting of word stress onto word stems and later onto the first syllable of the word (though English has an irregular stress, native words always have a fixed stress regardless of what is added to them)

Germanic languages differ from each other to a greater degree than do some other language families such as the Romance or Slavic languages. Roughly speaking, Germanic languages differ in how conservative or how progressive each language is with respect to an overall trend toward analyticity. Some, such as Icelandic, and to a lesser extent, German, have preserved much of the complex inflectional morphology inherited from the Proto-Indo-European language. Others, such as English, Swedish, and Afrikaans, have moved toward a largely analytic type.

Another characteristic of Germanic languages is verb second (V2) word order, which is quite uncommon cross-linguistically. This feature was not inherited from Proto-Germanic, but was probably already present in latent form, and may have begun with auxiliary verbs that were treated as sentence clitics, which were generally placed second. The later parallel innovation of V2 word order in the individual languages may have been a result of the loss of noun declension, which tended to 'fix' word order into its most common form. It is now shared by all modern Germanic languages except modern English which has more or less replaced the earlier V2 structure with fixed Subject–verb–object word order.

Writing

The earliest evidence of Germanic languages comes from names recorded in the 1st century by Tacitus (especially from his work Germania), but the earliest Germanic writing occurs in a single instance in the 2nd century BC on the Negau helmet.[8] From roughly the 2nd century AD, certain speakers of early Germanic varieties developed the Elder Futhark, an early form of the Runic alphabet. Early runic inscriptions also are largely limited to personal names, and difficult to interpret. The Gothic language was written in the Gothic alphabet developed by Bishop Ulfilas for his translation of the Bible in the 4th century.[9] Later, Christian priests and monks who spoke and read Latin in addition to their native Germanic varieties began writing the Germanic languages with slightly modified Latin letters. However, throughout the Viking Age, Runic alphabets remained in common use in Scandinavia. In addition to the standard Latin script, many Germanic languages use a variety of accent marks and extra letters, including umlauts, the ß (Eszett), IJ, Ø, Æ, Å, Ä, Ü, Ö, Ð, Ȝ, and the Latinized runes Þ and Ƿ (with its Latin counterpart W). In print, German used to be prevalently set in blackletter typefaces (e.g. fraktur or schwabacher) up until the 1940s (though see Antiqua–Fraktur dispute), whereas Kurrent and since the early 20th century Sütterlin was used for German handwriting.

History

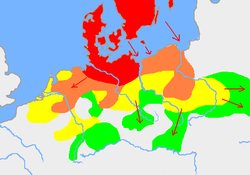

All Germanic languages are thought to be descended from a hypothetical Proto-Germanic, united by subjection to the sound shifts of Grimm's law and Verner's law. These probably took place during the Pre-Roman Iron Age of Northern Europe from ca. 500 BC, but other common innovations separating Germanic from Proto-Indo European suggest a common history of pre-Proto-Germanic speakers throughout the Nordic Bronze Age.

From the time of their earliest attestation, the Germanic varieties are divided into three groups: West, East, and North Germanic. Their exact relation is difficult to determine from the sparse evidence of runic inscriptions, and they remained mutually intelligible throughout the Migration period, so that some individual varieties are difficult to classify.

The 6th-century Lombardic language, for instance, may be a variety originally either Northern or Eastern, before being assimilated by West Germanic as the Lombards settled at the Elbe. The Western group would have formed in the late Jastorf culture, the Eastern group may be derived from the 1st-century variety of Gotland (see Old Gutnish), leaving southern Sweden as the original location of the Northern group. The earliest coherent Germanic text preserved is the 4th century Gothic translation of the New Testament by Ulfilas. Early testimonies of West Germanic are in Old Frankish (5th century), Old High German (scattered words and sentences 6th century, coherent texts 9th century) and Old English (coherent texts 10th century). North Germanic is only attested in scattered runic inscriptions, as Proto-Norse, until it evolves into Old Norse by about 800.

Longer runic inscriptions survive from the 8th and 9th centuries (Eggjum stone, Rök stone), longer texts in the Latin alphabet survive from the 12th century (Íslendingabók), and some skaldic poetry held to date back to as early as the 9th century.

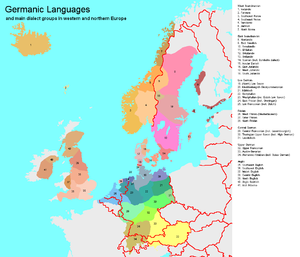

North Germanic languages West Germanic languages Dots indicate areas where multilingualism is common.

By about the 10th century, the varieties had diverged enough to make inter-comprehensibility difficult. The linguistic contact of the Viking settlers of the Danelaw with the Anglo-Saxons left traces in the English language, and is suspected to have facilitated the collapse of Old English grammar that resulted in Middle English from the 12th century.

The East Germanic languages were marginalized from the end of the Migration period. The Burgundians, Goths, and Vandals became linguistically assimilated by their respective neighbors by about the 7th century, with only Crimean Gothic lingering on until the 18th century.

During the early Middle Ages, the West Germanic languages were separated by the insular development of Middle English on one hand, and by the High German consonant shift on the continent on the other, resulting in Upper German and Low Saxon, with graded intermediate Central German varieties. By Early modern times, the span had extended into considerable differences, ranging from Highest Alemannic in the South to Northern Low Saxon in the North and, although both extremes are considered German, they are hardly mutually intelligible. The southernmost varieties had completed the second sound shift, while the northern varieties remained unaffected by the consonant shift.

The North Germanic languages, on the other hand, remained more unified, with the peninsular languages largely retaining mutual intelligibility into modern times.

Classification

Note that divisions between and among subfamilies of Germanic are rarely precisely defined; most form continuous clines, with adjacent varieties being mutually intelligible and more separated ones not.

Diachronic

The table below shows the succession of the significant historical stages of each language (vertically), and their approximate groupings in subfamilies (horizontally). Horizontal sequence within each group does not imply a measure of greater or lesser similarity.

Contemporary

All living Germanic languages belong either to the West Germanic or to the North Germanic branch. The West Germanic group is the larger by far, further subdivided into Anglo-Frisian on one hand, and Continental West Germanic on the other. Anglo-Frisian notably includes English and all its variants, while Continental West Germanic includes German (standard register and dialects) as well as Dutch (standard register and dialects).

- West Germanic languages

- High German languages (includes Standard German and its dialects)

- Central German

- East Central German

- West Central German

- Luxembourgish

- Pennsylvania German (spoken by the Amish and other groups in southeastern Pennsylvania)

- Upper German

- Yiddish

- Central German

- Low Franconian

- Dutch and its dialects

- Afrikaans (a separate standard language)

- Low German

- West Low German

- East Low German

- Plautdietsch (Mennonite Low German)

- Anglo-Frisian

- Frisian group

- English group

- English and its dialects

- Scots

- Yola (extinct)

- High German languages (includes Standard German and its dialects)

- North Germanic

Common linguistic features

Phonology

The oldest Germanic languages all share a number of features, assumed to be inherited from Proto-Germanic. Phonologically, this includes the important sound changes known as Grimm's Law and Verner's Law, which introduced a large number of fricatives; late Proto-Indo-European (PIE) had only one, /s/.

The main vowel developments are the merging (in most circumstances) of long and short /a/ and /o/, producing short /a/ and long /ō/. This likewise affected the diphthongs, with PIE /ai/ and /oi/ merging into /ai/, and PIE /au/ and /ou/ merging into /au/. PIE /ei/ developed into long /ī/. PIE long /ē/ developed into a vowel denoted as /ē1/ (often assumed to be phonetically [ǣ]), while a new, fairly uncommon long vowel /ē2/ developed in varied and not completely understood circumstances. Proto-Germanic had no front rounded vowels, although all Germanic languages except for Gothic subsequently developed them through the process of i-umlaut.

Proto-Germanic developed a strong stress accent on the first syllable of the root (although remnants of the original free PIE accent are visible due to Verner's Law, which was sensitive to this accent). This caused a steady erosion of vowels in unstressed syllables. In Proto-Germanic this had progressed only to the point that absolutely final short vowels (other than /i/ and /u/) were lost and absolutely final long vowels were shortened, but all of the early literary languages show a more advanced state of vowel loss. This ultimately resulted in some languages (e.g. modern English) in the loss of practically all vowels following the main stress, and the consequent rise of a very large number of monosyllabic words.

Morphology

The oldest Germanic languages have the typical complex inflected morphology of old Indo-European languages, with four or five noun cases; verbs marked for person, number, tense and mood; multiple noun and verb classes; few or no articles; and rather free word order. The old Germanic languages are famous for having only two tenses (present and past), with three PIE past-tense aspects (imperfect, aorist, and perfect/stative) merged into one and no new tenses (future, pluperfect, etc.) developing. There were three moods: indicative, subjunctive (developed from the PIE optative mood) and imperative. Gothic verbs had a number of archaic features inherited from PIE that were lost in the other Germanic languages with few traces, including dual endings, an inflected passive voice (derived from the PIE mediopassive voice), and a class of verbs with reduplication in the past tense (derived from the PIE perfect). The complex tense system of modern English (e.g. In three months, the house will still be being built or If you had not acted so stupidly, we would never have been caught) is almost entirely due to subsequent developments (although paralleled in many of the other Germanic languages).

Among the primary innovations in Proto-Germanic are the preterite present verbs, a special set of verbs whose present tense looks like the past tense of other verbs and which is the origin of most modal verbs in English; a past-tense ending (in the so-called "weak verbs", marked with -ed in English) that appears variously as /d/ or /t/, often assumed to be derived from the verb "to do"; and two separate sets of adjective endings, originally corresponding to a distinction between indefinite semantics ("a man", with a combination of PIE adjective and pronoun endings) and definite semantics ("the man", with endings derived from PIE n-stem nouns).

Strong vs. weak nouns and adjectives

Originally, adjectives in Proto-Indo-European followed the same declensional classes as nouns. The most common class (the o/ā class) used a combination of o-stem endings for masculine and neuter genders and ā-stems ending for feminine genders, but other common classes (e.g. the i class and u class) used endings from a single vowel-stem declension for all genders, and various other classes existed that were based on other declensions. A quite different set of "pronominal" endings was used for pronouns, determiners and words with related semantics (e.g. "all", "only").

An important innovation in Proto-Germanic was the development of two separate sets of adjective endings, originally corresponding to a distinction between indefinite semantics ("a man") and definite semantics ("the man"). The endings of indefinite adjectives were derived from a combination of pronominal endings with one of the common vowel-stem adjective declensions — usually the o/ā class (often termed the a/ō class in the specific context of the Germanic languages), but sometimes the i or u classes. Definite adjectives, however, had endings based on n-stem nouns. Originally both types of adjectives could be used by themselves, but already by Proto-Germanic times a pattern evolved whereby definite adjectives had to be accompanied by a determiner with definite semantics (e.g. a definite article, demonstrative pronoun, possessive pronoun, or the like), while indefinite adjectives were used in other circumstances (either accompanied by a word with indefinite semantics such as "a", "one" or "some", or unaccompanied).

In the 19th century, the two types of adjectives — indefinite and definite — were respectively termed "strong" and "weak", names which are still commonly used. These names were based on the appearance of the two sets of endings in modern German. In German, the distinctive case endings formerly present on nouns have largely disappeared, with the result that the load of distinguishing one case from another is almost entirely carried by determiners and adjectives. Furthermore, due to regular sound change, the various definite (n-stem) adjective endings coalesced to the point where only two endings (-e and -en) remain in modern German to express the 16 possible inflectional categories of the language (masculine/feminine/neuter/plural crossed with nominative/accusative/dative/genitive — modern German merges all genders in the plural). The indefinite (a/ō-stem) adjective endings were less affected by sound change, with six endings remaining (-, -e, -es, -er, -em, -en), cleverly distributed in a way that is capable of expressing the various inflectional categories without too much ambiguity. As a result, the definite endings were thought of as too "weak" to carry inflectional meaning and in need of "strengthening" by the presence of an accompanying determiner, while the indefinite endings were viewed as "strong" enough to indicate the inflectional categories even when standing alone. (This view is enhanced by the fact that modern German largely uses weak-ending adjectives when accompanying an indefinite article, and hence the indefinite/definite distinction no longer clearly applies.) By analogy, the terms "strong" and "weak" were extended to the corresponding noun classes, with a-stem and ō-stem nouns termed "strong" while n-stem nouns termed "weak".

However, in Proto-Germanic — and still in Gothic, the most conservative Germanic language — the terms "strong" and "weak" are not clearly appropriate. For one thing, there were a large number of noun declensions. The a-stem, ō-stem and n-stem declensions were the most common, and represented targets into which the other declensions were eventually absorbed, but this process occurred only gradually. Originally the n-stem declension was not a single declension but a set of separate declensions (e.g. -an, -ōn, -īn) with related endings, and these endings were in no way any "weaker" than the endings of any other declensions. (For example, among the 8 possible inflectional categories of a noun — singular/plural crossed with nominative/accusative/dative/genitive — masculine an-stem nouns in Gothic include 7 endings and feminine ōn-stem nouns include 6 endings, meaning there is very little ambiguity of "weakness" in these endings and in fact much less than in the German "strong" endings.) Although it is possible to group the various noun declensions into three basic categories — vowel-stem, n-stem and other-consonant-stem (aka "minor declensions") — the vowel-stem nouns do not display any sort of unity in their endings that supports grouping them together with each other but separate from the n-stem endings.

It is only in later languages that the binary distinction between "strong" and "weak" nouns become more relevant. In Old English, the n-stem nouns form a single, clear class, but the masculine a-stem and feminine ō-stem nouns have little in common with each other, and neither has much similarity to the small class of u-stem nouns. Similarly, in Old Norse, the masculine a-stem and feminine ō-stem nouns have little in common with each other, and the continuations of the masculine an-stem and feminine ōn/īn-stem nouns are also quite distinct. It is only in modern German that the various vowel-stem nouns have merged to the point that a binary strong/weak distinction clearly applies.

As a result, newer grammatical descriptions of the Germanic languages often avoid the terms "strong" and "weak" except in conjunction with German itself, preferring instead to use the terms "indefinite" and "definite" for adjectives and to distinguish nouns by their actual stem class.

In English, both two sets of adjective endings were lost entirely in the late Middle English period.

Linguistic developments

The subgroupings of the Germanic languages are defined by shared innovations. It is important to distinguish innovations from cases of linguistic conservatism. That is, if two languages in a family share a characteristic that is not observed in a third language, that is evidence of common ancestry of the two languages only if the characteristic is an innovation compared to the family's proto-language.

The following innovations are common to the Northwest Germanic languages (all but Gothic):

- The lowering of /u/ to /o/ in initial syllables before /a/ in the following syllable ("a-Umlaut", traditionally called Brechung)

- "Labial umlaut" in unstressed medial syllables (the conversion of /a/ to /u/ and /ō/ to /ū/ before /m/, or /u/ in the following syllable)[12]

- The conversion of /ē1/ into /ā/ (vs. Gothic /ē/) in initial syllables[13]

- The raising of final /ō/ to /u/ (Gothic lowers it to /a/)

- The monophthongisation of /ai/ and /au/ to /ǣ/ and /ō/ in non-initial syllables (however, evidence for the development of /au/ in medial syllables is lacking)

- The development of an intensified demonstrative ending in /s/ (reflected in English "this" compared to "the")

- The use of /ē2/ in the preterite of Class VII strong verbs in North and West Germanic, while Gothic uses reduplication (e.g. Gothic haihait; ON, OE hēt, preterite of the Gmc verb *haitan "to be called")[14] as part of a comprehensive reformation of the Gmc Class VII from a reduplicating to a new ablaut pattern, which presumably started in verbs beginning with vowel or /h/[15] (a development which continues the general trend of de-reduplication in Gmc[16]); there are forms (such as OE dial. heht instead of hēt) which retain traces of reduplication even in West and North Germanic

The following innovations are also common to the Northwest Germanic languages, but represent areal changes:

- Proto-Germanic /z/ > /r/ (e.g. Gothic dius; ON dȳr, OHG tior, OE dēor, "wild animal"); note that this is not present in Proto-Norse and must be ordered after West Germanic loss of final /z/

- Germanic umlaut

The following innovations are common to the West Germanic languages:

- Loss of final /z/ (except in short monosyllables)

- Change of voiced dental fricative /ð/ to stop /d/

- Change of voiceless dental fricative /þ/ to stop /d/ after /l/ (except when /þ/ is word-final)[17]

- West Germanic gemination of consonants, except r, before /j/ in short-stemmed words (gemination of /p/, /t/, /k/ and /h/ is also observed before liquids), but not if /j/ (or a liquid) is vocalised (becomes syllabic) word-finally

- The simplification of /ngw/ to /ng/

- A particular type of umlaut /e-u-i/ > /i-u-i/

- Loss of /j/ before /i/ and /w/ before /u/ in endings

- The change of /b/ or /g/ to /w/ before nasal consonant[18]

- Changes to the 2nd person singular past-tense: Replacement of the past-singular stem vowel with the past-plural stem vowel, and substitution of the ending -t with -i

- Short forms (*stān, stēn, *gān, gēn) of the verbs for "stand" and "go"; but note that Crimean Gothic also has gēn

- The development of a gerund

The following innovations are common to the Ingvaeonic subgroup of the West Germanic languages:

- The so-called Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law, which (e.g.) converted *munþ "mouth" (cf. Old High German mund) into *mūþ (cf. Old English mūþ).

- The loss of the Germanic reflexive pronoun

- The reduction of the three Germanic verbal plural forms into one form ending in -þ

- The development of Class III weak verbs into a relic class consisting of four verbs (*sagjan "to say", *hugjan "to think", *habjan "to have", *libjan "to live")

- The split of the Class II weak verb ending *-ō- into *-ō-/-ōja-

- Development of a plural ending *-ōs in a-stem nouns (note, Gothic also has -ōs, but this is an independent development, caused by terminal devoicing of *-ōz; Old Frisian has -ar, which is thought to be a late borrowing from Danish)

- Merger of the accusative and dative in first and second person pronouns (also shared by Old Low Franconian)

- Possibly, the monophthongization of Germanic *ai to ē/ā (this may represent independent changes in Old Saxon and Anglo-Frisian)

The following innovations are common to the Anglo-Frisian subgroup of the Ingvaeonic languages:

- Raising of nasalized a, ā into o, ō

- Anglo-Frisian brightening: Fronting of non-nasal a, ā to æ,ǣ when not followed by n or m

- Metathesis of CrV into CVr, where C represents any consonant and V any vowel

- Monophthongization of ai into ā

Vocabulary comparison

Several of the terms in the table below have had semantic drift. For example, the form Sterben and other terms for die are cognates with the English word starve. There is also at least one example of a common borrowing from a non-Germanic source (ounce and its cognates from Latin).

| English | Scots | West Frisian | Afrikaans | Dutch | Dutch (Limburgish) | Low German | Low German (Groningen) | Middle German (Luxemburgish) |

German | Gothic | Icelandic | Faroese | Swedish | Danish | Norwegian (Bokmål) | Norwegian (Nynorsk) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apple | aiple/aipil | apel | appel | appel | appel | Appel | Abbel | Apel | Apfel | aplus | epli | epli[19] | äpple | æble | eple | eple |

| board | buird | board | bord | bord | bórdj/telleur | Boord | Bred | Briet | Brett[20] | baúrd | borð | borð | bord | bord | bord | bord |

| beech | beech | boeke | beuk | beuk | beuk | Boeoek / Böök | Beukenboom | Bich | Buche | bōka[21]/-bagms | beyki | bók(artræ) | bok | bøg | bok | bok / bøk |

| book | beuk/buik | boek | boek | boek | book | Book | Bouk | Buch | Buch | bōka | bók | bók | bok | bog | bok | bok |

| breast | breest | boarst | bors | borst | boors | Bost | Bôrst | Broscht | Brust | brusts | brjóst | bróst / bringa | bröst | bryst | bryst | bryst |

| brown | broun | brún | bruin | bruin | broen | bruun | broen | brong | braun | bruns | brúnn | brúnur | brun | brun | brun | brun |

| day | day | dei | dag | dag | daag | Dag | Dag | Do | Tag | dags | dagur | dagur | dag | dag | dag | dag |

| dead | deid | dea | dood | dood | doed | dood | dood | dout | tot | dauþs | dauður | deyður | död | død | død | daud |

| die (starve) | dee | stjerre | sterf | sterven | stèrve | sterven / starven / döen | staarven | stierwen | sterben | diwan | deyja | doyggja | dö | dø | dø | døy / starva |

| enough | eneuch | genôch | genoeg | genoeg | genóg | noog | genog | genuch | genug | ganōhs | nóg | nóg/nógmikið | nog | nok | nok | nok |

| finger | finger | finger | vinger | vinger | veenger | Finger | Vinger | Fanger | Finger | figgrs | fingur | fingur | finger | finger | finger | finger |

| give | gie | jaan | gee | geven | geve | geven | geven | ginn | geben | giban | gefa | geva | ge / giva | give | gi | gje(va) |

| glass | gless | glês | glas | glas | glaas | Glas | Glas | Glas | Glas | – | glas | glas | glas | glas | glass | glas |

| gold | gowd | goud | goud | goud | goud / góldj | Gold | Gold | – | Gold | gulþ | gull | gull | guld / gull | guld | gull | gull |

| good | guid | gód | goed | goed | good | good | goud | gutt | gut | gōþ(is) | góð(ur) / gott | góð(ur) / gott | god | god | god | god |

| hand | haund | hân | hand | hand | hand | Hand | Haand | Hand | Hand | handus | hönd | hond | hand | hånd | hånd | hand |

| head | heid | holle | hoof[22] / kop[23] | hoofd / kop[23] | kop[23] | Kopp[23] / höved | Heufd / Kop[23] | Kopp[23] | Haupt / Kopf[23] | háubiþ | höfuð | høvd / høvur | huvud | hoved | hode | hovud |

| high | heich | heech | hoog | hoog | hoeg | hoog | hoog / höch | héich | hoch | háuh | hár | høg / ur | hög | høj | høy / høg | høg |

| home | hame | hiem | heim[24] / tuis[25] | heem, heim[24] / thuis[25] | thoes[25] | Tohuus[25] / heem | Thoes[25] | Heem | Heim | háimōþ | heim | heim | hem | hjem | hjem / heim | heim |

| hook / crook | heuk/huik | hoek | haak | haak | haok | Haak | Hoak | Krop / Kramp | Haken | kramppa | haki / krókur | krókur / ongul | hake / krok | hage / krog | hake / krok | hake / krok[26] |

| house | hoose/houss | hûs | huis | huis | hoes | Huus | Hoes | Haus | Haus | hūs | hús | hús | hus | hus | hus | hus |

| many | mony/monie | mannich / mennich | baie / menige | menig | minnig | Mennig | Ìnde | – | manch | manags | margir | mangir / nógvir | många | mange | mange | mange |

| moon | muin | moanne | maan | maan | maon | Maan | Moan | Mound | Mond | mēna | máni / tungl | máni | måne | måne | måne | måne |

| night | nicht | nacht | nag | nacht | nach | Nach / Nacht | Nacht | Nuecht | Nacht | nótt | nótt | nátt | natt | nat | natt | natt |

| no (nay) | nae | nee | nee | nee(n) | nei | nee | nee / nai | nee(n) | nee / nein / nö | nē | nei | nei | nej / nä | nej / næ | nei | nei |

| old (but: elder, eldest) | auld | âld | oud | oud | aajt (old) / gammel (decayed) | old / gammelig | old / olleg | aalt | alt | sineigs | gamall (but: eldri, elstur) / aldinn | gamal (but: eldri, elstur) | gammal (but: äldre, äldst) | gammel (but: ældre, ældst) | gammel (but: eldre, eldst) | gam(m)al (but: eldre, eldst) |

| one | ane | ien | een | een | ein | een | aine | een | eins | áins | einn | ein | en | en | en | ein |

| ounce | unce | ûns | ons | ons | óns | Ons | Onze | – | Unze | unkja | únsa | únsa | uns | unse | unse | unse / unsa |

| snow | snaw | snie | sneeu | sneeuw | sjnie | Snee | Snij / Snèj | Schlue | Schnee | snáiws | snjór | kavi / snjógvur | snö | sne | snø | snø |

| stone | stane | stien | steen | steen | stein | Steen | Stain | Steen | Stein | stáins | steinn | steinur | sten | sten | stein | stein |

| that | that | dat | daardie / dit | dat / die | dat / tot | dat / dit | dat / dij | dat | das | þata | það | tað | det | det | det | det |

| two / twain | twa | twa | twee | twee | twie | twee | twij / twèje | zoo / zwou / zwéin | zwei/zwo | twái | tveir / tvær / tvö | tveir / tvey / tvær / tvá | två / tu | to | to | to[27] |

| who | wha | wa | wie | wie | wee | wokeen | wel | wien | wer | Ƕas / hwas | hver | hvør | vem | hvem | hvem | kven |

| worm | wirm | wjirm | wurm | worm | weurm | Worm | Wörm | Wuerm | Wurm | maþa | maðkur / ormur | maðkur / ormur | mask / orm [28] | orm | makk / mark / orm [28] | makk/mark/orm[28] |

| English | Scots | West Frisian | Afrikaans | Dutch | Dutch (Limburgish) | Low German | Low German (Groningen) | Middle German (Luxemburgish) |

German | Gothic | Icelandic | Faroese | Swedish | Danish | Norwegian (Bokmål) | Norwegian (Nynorsk) |

See also

- Germanic verb and its various subordinated articles

- Language families and languages

- Non-Indo-European roots of Germanic languages

- List of Germanic and Latinate equivalents

- Germanisation and Anglicisation

- Germanic name

- Germanic placenames

- German name

- German placename etymology

- Isogloss

- Germanic substrate hypothesis

Notes

- ^ "Ethnologue on English". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Curtis, Andy. Color, Race, And English Language Teaching: Shades of Meaning. 2006, page 192.

- ^ SIL Ethnologue (2006). 95 million speakers of Standard German; 95 million including Middle and Upper German dialects; 120 million including Low Saxon and Yiddish.

- ^ Dutch, University College London

- ^ "Ethnologue on Afrikaans". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Holmberg, Anders and Christer Platzack (2005). "The Scandinavian languages". In The Comparative Syntax Handbook, eds Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Excerpt at Durham University.

- ^ Chuan-Chao Wang, Qi-Liang Ding, Huan Tao, Hui Li (2012). "Comment on "Phonemic Diversity Supports a Serial Founder Effect Model of Language Expansion from Africa"". Science. 335 (6069): 657. doi:10.1126/science.1207846. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Malcolm Todd (1992). The Early Germans. Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Cercignani, Fausto, The Elaboration of the Gothic Alphabet and Orthography, in «Indogermanische Forschungen», 93, 1988, pp. 168-185.

- ^ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ^ Campbell, Alistair (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 139.

- ^ But see Cercignani, Fausto, Indo-European ē in Germanic, in «Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung», 86/1, 1972, pp. 104-110.

- ^ See also Cercignani, Fausto, The Reduplicating Syllable and Internal Open Juncture in Gothic, in «Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung», 93/1, 1979, pp. 126-132.

- ^ Bethge, Richard (1900). "Konjugation des Urgermanischen". In Ferdinand Dieter (ed.). Laut- und Formenlehre der altgermanischen Dialekte (2. Halbband: Formenlehre). Leipzig: Reisland. p. 361.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Schumacher, Stefan (2005), "'Langvokalische Perfekta' in indogermanischen Einzelsprachen und ihr grundsprachlicher Hintergrund", in Meiser, Gerhard (ed.), Sprachkontakt und Sprachwandel. Akten der XI. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, 17. – 23. September 2000, Halle an der Saale, Wiesbaden: Reichert, pp. 603f.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coeditors=ignored (help) - ^ Campbell, Alistair (1959). Old English Grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 169.

- ^ Kuiper, F B J (1995). "Gothic 'bagms' and Old Icelandic 'ylgr'". North-Western European Language Evolution (NOWELE) (25): 63–88.

- ^ The cognate means 'potato'. The correct word is 'Súrepli'.

- ^ Brett is used in the South, Bord is used additionally in the North

- ^ Attested meaning 'letter', but also means beech in other Germanic languages, cf. Russian buk 'beech', bukva 'letter', maybe from Gothic.

- ^ Now only used in compound words such as hoofpyn (headache) and metaphorically, such as hoofstad (capital city).

- ^ a b c d e f g From an old Latin borrowing, akin to "cup".

- ^ a b Archaic: now only used in compound words such as 'heimwee' (homesickness).

- ^ a b c d e From a compound phrase akin to "to house"

- ^ ongel is also used for fishing hook.

- ^ Dialectally tvo / två / tvei (m) / tvæ (f) / tvau (n).

- ^ a b c The cognate orm usually means 'snake'.

External links

- Germanic Lexicon Project

- 'Hover & Hear' pronunciations of the same Germanic words in dozens of Germanic languages and 'dialects', including English accents, and compare instantaneously side by side

- Bibliographie der Schreibsprachen: Bibliography of medieval written forms of High and Low German and Dutch

- Ethnologue Report for Germanic

- Swadesh lists of Germanic basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)