Arecibo Observatory: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Clearing up run-on sentences and other problems, such as |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| image = [[File:Arecibo Observatory Aerial View.jpg|290px]] |

| image = [[File:Arecibo Observatory Aerial View.jpg|290px]] |

||

| caption = |

| caption = |

||

| organization = [[SRI International]], [[National Science Foundation |

| organization = [[SRI International]], [[National Science Foundation]], [[Cornell University]] |

||

| location = [[Arecibo, |

| location = In the area of [[Arecibo, Puerto Rico]] |

||

| wavelength = [[ |

| wavelength = [[electromagnetic spectrum]]: (3.00 cm to 1.00 [[meter]]) |

||

| built = 1963 |

| built = completed in [[1963]] |

||

| website = [http://www.naic.edu www.naic.edu] |

| website = [http://www.naic.edu www.naic.edu] |

||

| style = [[spherical reflector]] |

| style = [[spherical reflector]] |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| governing_body = Federal |

| governing_body = Federal |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Arecibo Observatory''' is a [[radio telescope]] in the mailing area of the city of [[Arecibo, Puerto Rico]]. |

The '''Arecibo Observatory''' is a [[radio telescope]] in the mailing area of the city of [[Arecibo, Puerto Rico]]. This [[observatory]] is operated by the company [[SRI International]] under cooperative agreement with the [[National Science Foundation]].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2011/05/new-consortium-to-run-arecibo-ob.html|title=New Consortium to Run Arecibo Observatory|first=Yudhijit|last=Bhattacharjee|work=[[Science (journal)|Science]]|date=20 May 2011|accessdate=2012-01-11}}</ref><ref name="sri">{{cite pressrelease|url=http://www.sri.com/news/releases/06022011.html|title=SRI International Selected by the National Science Foundation to Manage Arecibo Observatory|publisher=[[SRI International]]|date=2 June 2011|accessdate=2012-01-11}}</ref> This observatory is also called the '''National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center''', although "NAIC" refers to both the observatory and the staff that operates it.<ref name="2010RFP"/> |

||

The {{convert|305|m|ft|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} [[radio telescope]] here is the world's largest single-aperture telescope |

The {{convert|305|m|ft|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} [[radio telescope]] here is the world's largest single-aperture telescope, ever. It is used three major areas of research: [[radio astronomy]], [[aeronomy]], and [[radar astronomy]] observations of the larger objects of the [[Solar System]]. Scientists who want to use the telescope submit proposals, and these are evaluated by an independent scientific board. |

||

Since it it isually distinctive, this telescope has made notable appearances in motion picture and television productions. The telescope received additional recognition in [[1999] when it began to collect data for the [[SETI@home]] project. |

|||

This radio telescope has been listed on the American [[National Register of Historic Places]] beginning in 2008.<ref name="newlistings20081003"/><ref name="nrhpreg">{{cite web |title=National Register of Historic Places Registration: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center / Arecibo Observatory |url=http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/feature/weekly_features/IonosphereCenter.pdf |format=PDF |date=March 20, 2007 |author=Juan Llanes Santos |publisher=[[National Park Service]] |accessdate=October 21, 2009}} (72 pages, with many historic b&w photos and 18 color photos)</ref> It was the featured listing in the [[National Park Service]]'s weekly list of October 3, 2008.<ref name="featured">{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/nrlist.htm |title=Weekly List Actions |accessdate=October 21, 2009 |publisher=National Park Service| archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20091202223221/http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/nrlist.htm| archivedate= December 02 2009 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> The center was named an [[List of IEEE milestones|IEEE Milestone]] in 2001.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/Milestones:NAIC/Arecibo_Radiotelescope,_1963 |title=Milestones:NAIC/Arecibo Radiotelescope, 1963 |work=IEEE Global History Network |publisher=IEEE |accessdate=July 29, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

== Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center == |

== Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center == |

||

Opened in 1997, the Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center features interactive exhibits and displays about the operations of the radio telescope, [[astronomy]], and [[ |

Opened in 1997, the Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center features interactive exhibits and displays about the operations of the radio telescope, [[astronomy]], and [[atmospheric sciences|atmospheric science]]. The center is named after the financial foundation that honors [[Ángel Ramos (industrialist)| Ángel Ramos]], the owner of the [[El Mundo (Puerto Rico)|El Mundo]] newspaper and the founder of [[Telemundo]]. This foundation provided half of the money to build the visitors center, with the rest coming from private donations and from Cornell University. It is normally open Wednesday-Sunday, with additional opening hours on many holidays and school breaks. As of 2010, the admission fee is $10.00 for adults and $6.00 for children and seniors.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.naic.edu/general/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=162:vc-description&catid=107&Itemid=638|title=Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor's Center Schedule and Hours|accessdate=April 21, 2012}}</ref> |

||

== General information == |

== General information == |

||

Revision as of 23:24, 17 August 2012

| |

| Alternative names | National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center |

|---|---|

| Named after | Arecibo |

| Location(s) | Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Caribbean |

| Coordinates | 18°20′48″N 66°45′12″W / 18.3467°N 66.7533°W |

| Organization | SRI International, National Science Foundation, Cornell University |

| Observatory code | 251 |

| Altitude | 498 m (1,634 ft) |

| Wavelength | electromagnetic spectrum: (3.00 cm to 1.00 meter) |

| Built | completed in 1963 |

| Telescope style | spherical reflector |

| Diameter | 305 m (1,000 ft) |

| Collecting area | 73,000 square metres (790,000 sq ft) |

| Focal length | 265.109 m (869 ft 9+3⁄8 in)[citation needed] |

| Mounting | semi-transit telescope: fixed primary with secondary (Gregorian reflector) and a delay-line feed, each of which moves on tracks to point to different parts of the sky. |

| Enclosure | none |

| Website | www.naic.edu |

| | |

National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center | |

| Area | 118 acres (480,000 m2) |

|---|---|

| Architect | Gordon, William E; Kavanaugh, T.C. |

| NRHP reference No. | 07000525 |

| Added to NRHP | September 23, 2008[1] |

The Arecibo Observatory is a radio telescope in the mailing area of the city of Arecibo, Puerto Rico. This observatory is operated by the company SRI International under cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation.[2][3] This observatory is also called the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, although "NAIC" refers to both the observatory and the staff that operates it.[4]

The 305 m (1,000 ft) radio telescope here is the world's largest single-aperture telescope, ever. It is used three major areas of research: radio astronomy, aeronomy, and radar astronomy observations of the larger objects of the Solar System. Scientists who want to use the telescope submit proposals, and these are evaluated by an independent scientific board.

Since it it isually distinctive, this telescope has made notable appearances in motion picture and television productions. The telescope received additional recognition in [[1999] when it began to collect data for the SETI@home project.

This radio telescope has been listed on the American National Register of Historic Places beginning in 2008.[1][5] It was the featured listing in the National Park Service's weekly list of October 3, 2008.[6] The center was named an IEEE Milestone in 2001.[7]

Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center

Opened in 1997, the Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor Center features interactive exhibits and displays about the operations of the radio telescope, astronomy, and atmospheric science. The center is named after the financial foundation that honors Ángel Ramos, the owner of the El Mundo newspaper and the founder of Telemundo. This foundation provided half of the money to build the visitors center, with the rest coming from private donations and from Cornell University. It is normally open Wednesday-Sunday, with additional opening hours on many holidays and school breaks. As of 2010, the admission fee is $10.00 for adults and $6.00 for children and seniors.[8]

General information

The main collecting dish is 305 m (1,000 ft) in diameter, constructed inside the depression left by a karst sinkhole.[9] It contains the largest curved focusing dish on Earth, giving Arecibo the largest electromagnetic-wave-gathering capacity.[10] The dish surface is made of 38,778 perforated aluminum panels, each measuring about 3 by 6 feet (1 by 2 m), supported by a mesh of steel cables.

The telescope has three radar transmitters, with effective isotropic radiated powers of 20 TW at 2380 MHz, 2.5 TW (pulse peak) at 430 MHz, and 300 MW at 47 MHz.

The telescope is a spherical reflector, not a parabolic reflector. To aim the telescope, the receiver is moved to intercept signals reflected from different directions by the spherical dish surface. A parabolic mirror would induce a varying astigmatism when the receiver is in different positions off the focal point, but the error of a spherical mirror is the same in every direction.

The receiver is located on a 900-ton platform which is suspended 150 m (500 ft) in the air above the dish by 18 cables running from three reinforced concrete towers, one of which is 110 m (365 ft) high and the other two of which are 80 m (265 ft) high (the tops of the three towers are at the same elevation). The platform has a 93-meter-long rotating bow-shaped track called the azimuth arm on which receiving antennas, secondary and tertiary reflectors are mounted. This allows the telescope to observe any region of the sky within a forty-degree cone of visibility about the local zenith (between −1 and 38 degrees of declination). Puerto Rico's location near the equator allows Arecibo to view all of the planets in the Solar System, though the round trip light time to objects beyond Saturn is longer than the time the telescope can track it, preventing radar observations of more distant objects.

Design and architecture

The Arecibo telescope was built between the summer of 1960 and November 1963, by William E. Gordon of Cornell University, who intended to use it to study Earth's ionosphere.[11][12][13] Originally, a fixed parabolic reflector was envisioned, pointing in a fixed direction with a 150 m (500 ft) tower to hold equipment at the focus. This design would have limited its use in other areas of research, such as planetary science and radio astronomy, which require the ability to point at different positions in the sky and to track those positions for an extended period as Earth rotates. Ward Low of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) pointed out this flaw, and put Gordon in touch with the Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratory (AFCRL) in Boston, Massachusetts, where one group headed by Phil Blacksmith was working on spherical reflectors and another group was studying the propagation of radio waves in and through the upper atmosphere. Cornell University proposed the project to ARPA in the summer of 1958 and a contract was signed between the AFCRL and the University in November 1959. Cornell University and Sears published a request for proposals (RFP) asking for a design to support a feed moving along a spherical surface 435 feet (133 m) above the stationary reflector. The RFP suggested a tripod or a tower in the center to support the feed. At Cornell University on the day the project for the design and construction of the antenna was announced, Gordon had also envisioned a 435 ft (133 m) tower located in the center of the 1,000 ft (300 m) reflector for the feed's support.

George Doundoulakis, who directed research at General Bronze Corporation in Garden City, New York, along with Sears, who directed Internal Design at Digital B & E Corporation, New York, received the RFP from Cornell University for the antenna design, and studied the idea of suspending the feed with his brother, Helias Doundoulakis, a civil engineer. George Doundoulakis identified the problem that a tower or tripod would have presented around the center, the most important area of the reflector, and devised a more efficient, cost-effective approach by suspending the feed. He presented his proposal to Cornell, by using a doughnut truss suspended by four cables from four towers above the reflector, and providing along its edge a rail track for the azimuthal positioning of the feed. A second truss, in the form of an arc, or arch, was to be suspended below, which would rotate on the rails through 360 degrees. The arc also provided rails onto which the unit supporting the feed would move to provide for the elevational positioning of the feed. A counter-weight would move symmetrically opposite to the feed for stability, and the entire feed could be lowered and raised if a hurricane were present. Helias Doundoulakis ultimately designed the cable suspension system which was adopted in the final construction. Although the present configuration is substantially the same as the original drawings by George and Helias (with the exception of the suspension of the feed positioning assembly by three towers rather than the four towers in the original proposal), the U.S. Patent office granted Helias a patent[14] for the brothers' innovative idea. William J. Casey, later to be the director of the Central Intelligence Agency under President Ronald Reagan, was also an assignee on the patent.

Construction began in the summer of 1960, with the official opening on November 1, 1963.[15] As the primary dish is spherical, its focus is along a line rather than at a single point (as would be the case for a parabolic reflector); therefore, complicated line feeds had to be used to carry out observations. Each line feed covered a narrow frequency band (2–5% of the center frequency of the band) and a limited number of line feeds could be used at any one time, limiting the flexibility of the telescope.

The telescope has been upgraded several times. Initially, when the maximum expected operating frequency was about 500 MHz, the surface consisted of half-inch galvanized wire mesh laid directly on the support cables. In 1974, a high-precision surface consisting of thousands of individually adjustable aluminum panels replaced the old wire mesh, and the highest usable frequency was raised to about 5,000 MHz. A Gregorian reflector system was installed in 1997, incorporating secondary and tertiary reflectors to focus radio waves at a single point. This allowed the installation of a suite of receivers, covering the whole 1–10 GHz range, that could be easily moved onto the focal point, giving Arecibo a new flexibility. At the same time, a ground screen was installed around the perimeter to block the ground's thermal radiation from reaching the feed antennas, and a more powerful 2,400 MHz transmitter was installed.

Research and discoveries

Many significant scientific discoveries have been made using the Arecibo telescope. On April 7, 1964, shortly after it began operations, Gordon Pettengill's team used it to determine that the rotation rate of Mercury was not 88 days, as previously thought, but only 59 days.[16] In 1968, the discovery of the periodicity of the Crab Pulsar (33 milliseconds) by Lovelace and others provided the first solid evidence that neutron stars exist.[17] In 1974, Hulse and Taylor discovered the first binary pulsar PSR B1913+16,[18] an accomplishment for which they later received the Nobel Prize in Physics. In 1982, the first millisecond pulsar, PSR B1937+21, was discovered by Donald C. Backer, Shrinivas Kulkarni, Carl Heiles, Michael Davis, and Miller Goss.[19] This object spins 642 times per second, and until the discovery of PSR J1748-2446ad in 2005, it was the fastest-spinning pulsar known.

In August 1989, the observatory directly imaged an asteroid for the first time in history: 4769 Castalia.[20] The following year, Polish astronomer Aleksander Wolszczan made the discovery of pulsar PSR B1257+12, which later led him to discover its three orbiting planets and a possible comet.[21][22] These were the first extra-solar planets discovered. In 1994, John Harmon used the Arecibo radio telescope to map the distribution of ice in the poles of Mercury.[23]

In January 2008, detection of prebiotic molecules methanimine and hydrogen cyanide were reported from Arecibo Observatory radio spectroscopy measurements of the distant starburst galaxy Arp 220.[24]

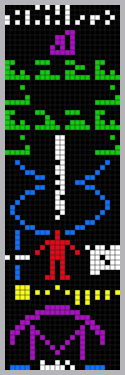

The Arecibo message

In 1974, the Arecibo message, an attempt to communicate with potential extraterrestrial life, was transmitted from the radio telescope toward the globular cluster M13, about 25,000 light-years away.[25] The 1,679 bit pattern of 1s and 0s defined a 23 by 73 pixel bitmap image that included numbers, stick figures, chemical formulas, and a crude image of the telescope itself.[26] Terrestrial aeronomy experiments include the Coqui 2 experiment.

Other uses

The telescope also had military intelligence uses; among them, locating Soviet radar installations by detecting their signals bouncing off the Moon.

Arecibo is also the source of data for the SETI@home and Astropulse distributed computing projects put forward by the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley and was used for the SETI Institute's Project Phoenix observations.[27]

Funding issues

A report by the division of Astronomical Sciences of the National Science Foundation, made public on 2006-11-03, recommended substantially decreased astronomy funding for Arecibo Observatory, ramping down from US$10.5M in 2007 to US$4M in 2011.[28][29] If other sources of money cannot be obtained, the observatory would close. The report also advised that 80% of the observation time be allocated to the surveys already in progress, reducing the time available for other scientific work. NASA gradually eliminated its share of the planetary radar funding at Arecibo from 2001–2006.[30]

Academics and researchers responded by organizing to protect and advocate for the observatory. They established the Arecibo Science Advocacy Partnership (ASAP), meant to advance the scientific excellence of Arecibo Observatory research and to publicize its accomplishments in astronomy, aeronomy and planetary radar.[31] ASAP's goals include mobilizing the existing broad base of support for Arecibo science within the fields it serves directly, the broad scientific community, and the general public; provide a forum for the Arecibo research community and enhance communication within it; promote the potential of Arecibo for groundbreaking science, and suggest the paths that will maximize it into the foreseeable future; showcase the broad impact and far-reaching implications of the science currently carried out with this unique instrument.[31]

Contributions by the government of Puerto Rico may be one way to help fill the funding gap, but are controversial and uncertain. At town hall meetings about the potential closure, Puerto Rico Senate President Kenneth McClintock announced an initial local appropriation of $3 million during fiscal year 2008 to fund a major maintenance project to restore the three pillars from which the antenna platform is suspended to their original condition, pending inclusion in the next bond issue.[32] The bond authorization, with the $3 million appropriation, was approved by the Senate of Puerto Rico on November 14, 2007, the first day of a special session called by Aníbal Acevedo Vilá.[33] The Puerto Rico House of Representatives repeated this action on June 30, 2008. The Governor signed the measure into law in August 2008.[34] These funds were made available in the second half of 2009.

José Serrano, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives Appropriations Committee, asked the National Science Foundation to keep Arecibo in operation in a letter released on September 19, 2007.[35] Language similar to that in the September 19 letter was included in the FY'08 omnibus spending bill. In October 2007, Puerto Rico's Resident Commissioner (now governor), Luis Fortuño, along with Dana Rohrabacher, filed legislation to assure the continued operation of the facility.[36] A similar bill was filed in the United States Senate in April 2008 by the junior Senator from New York, Hillary Clinton.[37]

As the Arecibo facility is owned by the United States, direct donations by private or corporate donors cannot be made. However, as a non-profit, 403(c)(3) charitable institution, Cornell University (and in the future, SRI International) will accept contributions on behalf of Arecibo Observatory.[38] It has been suggested by at least one member of the NAIC staff that Google purchase advertising space on the dish as one means of securing additional non-government funds.[39]

In September 2007, in an open letter to researchers, the NSF clarified the status of the budget issue for NAIC, stating that the present plan, if implemented, may hit the targeted budgetary revision.[40] No mention of private funding was made. However, it need be noted that the NSF is undertaking studies to mothball, or deconstruct the facility and return it to its natural setting in the event that the budget target is not achieved. In November 2007, The Planetary Society urged Congress to prevent the Arecibo Observatory from closing due to insufficient funds,[41] since the radar contributes heavily[42] to the accuracy of asteroid impact prediction, and they believe continued operation will reduce the cost of mitigation (that is, deflection of a near-Earth asteroid on collision to Earth), should that be necessary. Also in November of that year the The New York Times described the consequences of the budget cuts at the site.[43]

In July 2008, the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph reported that the funding crisis, due to federal budget cuts, was still very much alive.[44] The SETI@home program is using the telescope as a primary source for the research. The program is urging people to send a letter to their political representatives, in support of full federal funding of the observatory.[45]

NAIC received US$3.1 million from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, which was used for infrastructure improvements and for a second, much smaller, antenna to be used for VLBI and student training.[46] This allotment was an increase of around 30% over the FY2009 budget. However, the FY2010 funding request by NSF was cut by US$1.2 million (−12.5% over the non-ARRA supported FY2009 budget) in light of their continued plans to reduce funding.[47] The 2011 NSF budget was reduced by a further US$1.6 million, −15% with respect to 2010, with a further US$1 million reduction projected by FY2014.[48] In addition, "NSF will decertify NAIC as a Federally Funded Research and Development Center (FFRDC) upon award of the next cooperative agreement for its management and operation."[48]

Beginning in FY 2010, NASA began contributing $2M/year for Planetary Science, particularly the study of near-Earth objects, at Arecibo. NASA is implementing this funding through its Near Earth Object Observations program.[49]

In 2010, the National Science Foundation issued a call for proposals for the management of NAIC beginning in FY2012.[4] On May 12, 2011, The National Science Foundation informed Cornell University that it would no longer be the operator of the NAIC, and thus of the Arecibo Observatory, as of October 1, 2011. The new operator is SRI International, along with two other managing partners, Universities Space Research Association and Universidad Metropolitana, with a number of other collaborators.[3][50]

In popular culture

- The Arecibo Observatory was featured on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage in Part 12 "Encyclopaedia Galactica."

- The Arecibo Observatory is featured at the end of James Burke's TV series Connections in Part 3 "Distant Voices."

- Arecibo Observatory was used as a filming location in the climax of the James Bond movie GoldenEye and as a level in the accompanying Nintendo 64 videogame GoldenEye 007.

- The film Contact features Arecibo, where the main character uses the facility as part of a SETI project.

- Fox Mulder was sent to the Arecibo Observatory in The X-Files episode "Little Green Men".

- Songwriter and author Jimmy Buffett mentions the "giant telescope" in his book Where Is Joe Merchant?, and in the lyrics to the song "Desdemona's Building A Rocket Ship".

- The musicians Boxcutter, Lustmord, and Little Boots have all released albums named Arecibo.

- The observatory is featured in the film Species, the James Gunn novel The Listeners (1972), the Robert J. Sawyer novel Rollback, and the Mary Doria Russell novel The Sparrow.

- Arecibo Observatory also featured in the action movie The Losers (2010).

- In the video game Just Cause 2 there is a large radio observatory called PAN MILSAT that is very similar in appearance to Arecibo Observatory.

- Internet radio station Arecibo Radio is named after the observatory.

Arecibo Observatory Directors

- 1963-1965, Dr. William E. Gordon (Ph.D., Cornell University)

- 1965-1966, John W. Findlay (Ph.D., University of Cambridge)

- 1966-1968, Dr. Frank Drake (Ph.D., Harvard University)

- 1968-1970, Dr. Gordon Pettengill (Ph.D., UC Berkeley)

- 1971-1973, Dr. Tor Hagfors (Ph.D., University of Oslo)

- 1973-1981, Dr. Harold D. Craft Jr. (Ph.D., Cornell University)

- 1981-1987, Dr. Donald B. Campbell (Ph.D., Cornell University)

- 1988-1989 (interim) Dr. Riccardo Giovanelli (Ph.D., University of Bologna)

- 1988-1992, Dr. Michael M. Davis (Ph.D., Leiden University)

- 1992-2003, Dr. Daniel R. Altschuler (Ph.D., Brandeis University)

- 2003-2006, Dr. Sixto A. González (Ph.D., Utah State University)

- 2006-2007 (interim) Dr. Timothy L. Hankins (Ph.D., University of California at San Diego)

- 2007-2008, Dr. Robert B. Kerr (Ph.D., University of Michigan)

- 2008-2011, (interim 2008) Dr. Michael C. Nolan (Ph.D., University of Arizona)

- 2011–present, Dr. Robert B. Kerr (Ph.D., University of Michigan)

See also

- Air Force Research Laboratory

- List of radio telescopes

- Sixto A. González, former director of the Arecibo Observatory (2003–2006)

- William E. Gordon, founder and first director of the observatory (AIO 1963–1965)

- Tor Hagfors, former director of the Arecibo Observatory (1971–1973) and also of NAIC (October 1982 to September 1992).

- Helias Doundoulakis[51]

- UPRM Planetarium

References

- ^ a b National Park Service (October 3, 2008). "Weekly List Actions". Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit (May 20, 2011). "New Consortium to Run Arecibo Observatory". Science. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "SRI International Selected by the National Science Foundation to Manage Arecibo Observatory" (Press release). SRI International. June 2, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "NSF request for proposals issued in 2010" (PDF). Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ^ Juan Llanes Santos (March 20, 2007). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center / Arecibo Observatory" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved October 21, 2009. (72 pages, with many historic b&w photos and 18 color photos)

- ^ "Weekly List Actions". National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 02 2009. Retrieved October 21, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Milestones:NAIC/Arecibo Radiotelescope, 1963". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ "Ángel Ramos Foundation Visitor's Center Schedule and Hours". Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ David Brand (January 21, 2003). "Astrophysicist Robert Brown, leader in telescope development, named to head NAIC and its main facility, Arecibo Observatory". Cornell University. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ Frederic Castel (May 8, 2000). "Arecibo: Celestial Eavesdropper". Space.com. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ "IEEE History Center: NAIC/Arecibo Radiotelescope, 1963". Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ "Pictures of the construction of Arecibo Observatory (start to finish)". National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center. Archived from the original on May 05 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Description of Engineering of Arecibo Observatory". Acevedo, Tony (June 2004). Archived from the original on May 04 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ US patent 3273156, Helias Doundoulakis, "Radio Telescope having a scanning feed supported by a cable suspension over a stationary reflector", issued 1966-09-13

- ^ "Arecibo Observatory". History.com. Retrieved September 2, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Seth Shostak (March 19, 2002). "The Arecibo Diaries: The Biggest is Best". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Richard V.E. Lovelace. "Discovery of the Period of the Crab Nebula Pulsar" (PDF). Cornell University. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hulse, R.A., and Taylor, J.H. (1975). Discovery of a pulsar in a binary system. pp. 195, L51–L53.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D. Backer; et al. (1982). "A millisecond pulsar". Nature. 300 (5893): 315–318. Bibcode:1982Natur.300..615B. doi:10.1038/300615a0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ "Asteroid 4769 Castalia (1989 PB)". NASA. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wolszczan, A. (1994). Confirmation of Earth Mass Planests Orbiting the Milliesecond Pulsar PSR: B1257+12. p. 538.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Daniel Fischer (2002). "A comet orbiting a pulsar?". The Cosmic Mirror (244).

- ^ Harmon, J.K., M.A. Slade, R.A. Velez, A. Crespo, M.J. Dryer, and J.M. Johnson (1994). Radar Mapping of Mercury's Polar Anomalies. p. 369.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Staff (January 15, 2008). "Life's Ingredients Detected In Far Off Galaxy". ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily LLC. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

[Article] Adapted from materials provided by Cornell University.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Larry Klaes (November 30, 2005). "Making Contact". Ithaca Times. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ Geaorge Cassiday. "The Arecibo Message". The University of Utah: Department of Physics. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Peter Backus (April 14, 2003). "Project Phoenix: SETI Prepares to Observe at Arecibo". Space.com. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ^ Roger Blandford (October 22, 2006). "From the Ground Up: Balancing the NSF Astronomy Program" (PDF). National Science Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2008. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rick Weiss (September 9, 2007). "Radio Telescope And Its Budget Hang in the Balance". The Washington Post. Arecibo, Puerto Rico: The Washington Post Company. p. A01. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

The cash crunch stems from a "senior review" completed last November at NSF. Its $200 million astronomy division – increasingly committed to ambitious, new projects but long hobbled by flat congressional budgets – was facing a deficit of at least $30 million by 2010.

- ^ Robert Roy Britt (December 20, 2001). "NASA Trims Arecibo Budget, Says Other Organizations Should Support Asteroid Watch". Space.com. Imaginova. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Areciboscience.org". Areciboscience.org. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Liz Arelis Cruz Maisonave. "Buscan frenar cierre de Radiotelescopio en Arecibo". El Vocero (in Spanish). Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Senado aprueba emisión de bonos de $450 millones". Primera Hora (in Spanish). November 14, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ Gerardo E, Alvarado León (August 10, 2008). Gobernador firma emisión de bonos.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ José E. Serrano (September 19, 2007). "Serrano concerned about potential Arecibo closure". serrano.house.gov. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Congress gets bill to save Arecibo Observatory". Cornell University. October 3, 2007. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jeannette Rivera-lyles (April 25, 2008). "Clinton turns attention to observatory in Puerto Rico". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 30, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Arecibo-observatory.org". Cornell and NAIC. 22 June 2008. Archived from the original on July 07 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

Our mission is to establish a new funding model to supplement NSF support and maintain operations of the observatory now and into the future.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

John Borland (September 10, 2007). "Should Google Sponsor Giant Radio Telescopes?" (blog). WIRED Blog Network. Chris Mitchell. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

Imagine the word 'Google' painted across that 19 acre dish," (Arecibo director) Kerr said. "What do you think that would be worth?

- ^ "Dear Colleague Letter: Providing Progress Update on Senior Review Recommendations" (Press release). The National Science Foundation. September 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 28, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Protecting the Earth[dead link]

- ^ Arecibo participated in 90 of the 111 asteroid radar observations in 2005–2007. See JPL's list of all asteroid radar observations.

- ^ Chang, K., "A Hazy Future for a 'Jewel' of Space Instruments.", New York Times, November 20, 2007

- ^ Jacqui Goddard, "Threat to world's most powerful radio telescope means we may not hear ET", Daily Telegraph, July 12, 2008

- ^ "Save Arecibo: Write to Congress". Retrieved July 19, 2008

- ^ "12-m Phase Reference Antenna". Naic.edu. June 28, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ "FY2010 Budget Request to Congress". Retrieved May 26, 2009

- ^ a b "Major multi-user research facilities" p. 35-38. Retrieved 2010 Feb. 10

- ^ "NASA Support to Planetary Radar" retrieved 2011 July 7

- ^ "SRI International to manage Arecibo Observatory". Cornell Chronicle. June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ "3,273,156 (1966-09-13) Helias Doundoulakis, Radio Telescope having a scanning feed supported by a cable suspension over a stationary reflector". U.S. Patent Office.

Further reading

- Friedlander, Blaine P. Jr. (November 14, 1997). "Research rockets, including an experiment from Cornell, are scheduled for launch into the ionosphere next year from Puerto Rico". Cornell University.

- Ruiz, Carmelo (March 3, 1998). "Activists protest US Navy radar project". Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space.

- Amir Alexander (July 3, 2008). "Budget Cuts Threaten Arecibo Observatory". The Planetary Society.

- Blaine Friedlander (June 10, 2008). "Arecibo joins global network to create 6,000-mile (9,700 km) telescope". EurekAlert.

- Lauren Gold (June 5, 2008). "Clintons (minus Hillary) visit Arecibo; former president urges more federal funding for basic sciences". Cornell university.

- Henry Fountain (December 25, 2007). "Arecibo Radio Telescope Is Back in Business After 6-Month Spruce-Up". New York Times.

- Entry into the National Register of Historic Places

External links

- 1963 works

- Astronomical observatories in Puerto Rico

- Cornell University buildings

- Historic districts in Puerto Rico

- Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmarks

- National Register of Historic Places in Puerto Rico

- National Science Foundation

- Radio telescopes

- Search for extraterrestrial intelligence

- Science museums in Puerto Rico

- University museums in Puerto Rico

- Museums in Arecibo, Puerto Rico

- GoldenEye

- SRI International