Leonard Nimoy: Difference between revisions

m →Illness and death: wrong way around. |

|||

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

In 2009, Nimoy was honored by his childhood hometown when the Office of Mayor [[Thomas Menino]] [[Proclamation|proclaimed]] the date of November 14, 2009, as ''Leonard Nimoy Day'' in the City of Boston.<ref>{{cite news |title=Hardly Illogical: Leonard Nimoy Day, November 14 |first=Shaula |last=Clark |url=http://blog.thephoenix.com/BLOGS/laserorgy/archive/2009/11/14/hardly-illogical-leonard-nimoy-day-november-14.aspx |newspaper=[[The Phoenix (newspaper)|Boston Phoenix]] |type=Blog |date=November 14, 2009 |accessdate=March 31, 2012}}</ref> |

In 2009, Nimoy was honored by his childhood hometown when the Office of Mayor [[Thomas Menino]] [[Proclamation|proclaimed]] the date of November 14, 2009, as ''Leonard Nimoy Day'' in the City of Boston.<ref>{{cite news |title=Hardly Illogical: Leonard Nimoy Day, November 14 |first=Shaula |last=Clark |url=http://blog.thephoenix.com/BLOGS/laserorgy/archive/2009/11/14/hardly-illogical-leonard-nimoy-day-november-14.aspx |newspaper=[[The Phoenix (newspaper)|Boston Phoenix]] |type=Blog |date=November 14, 2009 |accessdate=March 31, 2012}}</ref> |

||

===Illness and death=== |

|||

In February 2014, Nimoy revealed that he had been diagnosed with [[chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]] (COPD). On February 19, 2015, Nimoy was taken to UCLA Medical Center for chest pain and had been in and out of hospitals for the "past several months."<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/24/entertainment/leonard-nimoy-feat/ | title = Internet to Leonard Nimoy: Live long and prosper | first = Lisa Respers | last = France | date = February 24, 2015 | accessdate= February 27, 2015 | publisher = [[CNN]] }}</ref> |

In February 2014, Nimoy revealed that he had been diagnosed with [[chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]] (COPD). On February 19, 2015, Nimoy was taken to UCLA Medical Center for chest pain and had been in and out of hospitals for the "past several months."<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/24/entertainment/leonard-nimoy-feat/ | title = Internet to Leonard Nimoy: Live long and prosper | first = Lisa Respers | last = France | date = February 24, 2015 | accessdate= February 27, 2015 | publisher = [[CNN]] }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:15, 27 February 2015

This article is currently being heavily edited because its subject has recently died. Information about their death and related events may change significantly and initial news reports may be unreliable. The most recent updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

Leonard Nimoy | |

|---|---|

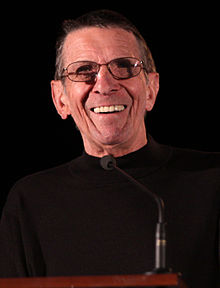

Nimoy at Phoenix Comicon in May 2011 | |

| Born | Leonard Simon Nimoy March 26, 1931 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 2015 (aged 83) Bel Air, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Complications from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, film director, poet, photographer, singer, songwriter |

| Years active | 1951–2013[1] |

| Television | Star Trek |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Adam Nimoy Julie Nimoy |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1953–1955[2] |

| Rank | |

| Website | www.LeonardNimoyPhotography.com |

Leonard Simon Nimoy (/ˈniːmɔɪ/; March 26, 1931 – February 27, 2015) was an American actor, film director, poet, singer and photographer. Nimoy was known for his role as Spock in the original Star Trek series (1966–69), and in multiple film, television and video game sequels.[3]

Nimoy was born to Jewish immigrant parents in Boston, Massachusetts. He began his career in his early twenties, teaching acting classes in Hollywood and making minor film and television appearances through the 1950s, as well as playing the title role in Kid Monk Baroni. Foreshadowing his fame as a semi-alien, he played Narab, one of three Martian invaders in the 1952 movie serial Zombies of the Stratosphere. In 1953, he served in the United States Army.

In 1965, he made his first appearance in the rejected Star Trek pilot The Cage, and went on to play the character of Mr. Spock until 1969, followed by eight feature films and guest slots in the various spin-off series. The character has had a significant cultural impact and garnered Nimoy three Emmy Award nominations; TV Guide named Spock one of the 50 greatest TV characters.[4][5] After the original Star Trek series, Nimoy starred in Mission: Impossible for two seasons, hosted the documentary series In Search of..., and narrated Civilization IV, as well as making several well-received stage appearances. More recently, he also had a recurring role in the science fiction series Fringe.

Nimoy's fame as Spock was such that both of his autobiographies, I Am Not Spock (1975) and I Am Spock (1995), were written from the viewpoint of sharing his existence with the character.[6][7]

Early life and education

Nimoy was born on March 26, 1931 in the West End[8] of Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Yiddish-speaking Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Iziaslav, Soviet Union (now Ukraine).[9][10][11] His parents left Iziaslav separately—his father first walking over the border into Poland—and reunited in the United States.[12] His mother, Dora (née Spinner), was a homemaker, and his father, Max Nimoy, owned a barbershop in the Mattapan section of the city.[13][14]

Nimoy began acting at the age of 8 in a children's and neighborhood theater.[12] His parents wanted him to attend college and pursue a stable career, or even learn to play the accordion—with which, his father advised, Nimoy could always make a living—but his grandfather encouraged him to become an actor.[15] His first major role was at 17, as Ralphie in an amateur production of Clifford Odets' Awake and Sing![11] Nimoy took drama classes at Boston College in 1953 but failed to complete his studies,[16] and in the 1970s studied photography at the University of California, Los Angeles.[15] He had an MA in Education from Antioch College, an honorary doctorate from Antioch University in Ohio, awarded for activism in Holocaust remembrance, the arts, and the environment,[17] and an honorary doctorate of humane letters from Boston University.[18]

Nimoy served as a sergeant in the United States Army from 1953 through 1955,[2] alongside fellow actor Ken Berry and architect Frank Gehry.

Acting career

Before and during Star Trek

Nimoy's film and television acting career began in 1951. After receiving the title role in the 1952 film Kid Monk Baroni, a story about a street punk turned professional boxer, he played more than 50 small parts in B movies, television series such as Perry Mason[19] and Dragnet, and serials such as Republic Pictures' Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952). To support his family, he often did other work, such as delivering newspapers.[20]

He played an Army sergeant in the 1954 science fiction thriller Them! and a professor in the 1958 science fiction movie The Brain Eaters, and had a role in The Balcony (1963), a film adaptation of the Jean Genet play. With Vic Morrow, he produced a 1966 version of Deathwatch, an English-language film version of Genet's play Haute Surveillance, adapted and directed by Morrow and starring Nimoy.

On television, Nimoy appeared as "Sonarman" in two episodes of the 1957–1958 syndicated military drama The Silent Service, based on actual events of the submarine section of the United States Navy. He had guest roles in the Sea Hunt series from 1958 to 1960 and a minor role in the 1961 The Twilight Zone episode "A Quality of Mercy". He also appeared in the syndicated Highway Patrol starring Broderick Crawford.

In 1959, Nimoy was cast as Luke Reid in the "Night of Decision" episode of the ABC/Warner Bros. western series Colt .45, starring Wayde Preston and directed by Leslie H. Martinson.[21]

Nimoy appeared four times in ethnic roles on NBC's Wagon Train, the No. 1 program of 1962. He portrayed Bernabe Zamora in "The Estaban Zamora Story" (1959), "Cherokee Ned" in "The Maggie Hamilton Story" (1960), Joaquin Delgado in "The Tiburcio Mendez Story" (1961) and Emeterio Vasquez in "The Baylor Crowfoot Story" (1962).

Nimoy appeared in Bonanza (1960), The Rebel (1960), Two Faces West (1961), Rawhide (1961), The Untouchables (1962), The Eleventh Hour (1962), Perry Mason (1963; playing murderer Pete Chennery in "The Case of the Shoplifter's Shoe", episode 13 of season 6), Combat! (1963, 1965), Daniel Boone, The Outer Limits (1964), The Virginian (1963–1965; first working with Star Trek co-star DeForest Kelley in "Man of Violence", episode 14 of season 2, in 1963), Get Smart (1966) and Mission: Impossible (1969–1971). He appeared again in the 1995 Outer Limits series. He appeared in Gunsmoke in 1962 as Arnie and in 1966 as John Walking Fox.

Nimoy and Star Trek co-star William Shatner first worked together on an episode of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., "The Project Strigas Affair" (1964). Their characters were from opposite sides of the Iron Curtain, though with his saturnine looks, Nimoy was the villain, with Shatner playing a reluctant U.N.C.L.E. recruit.

On the stage, Nimoy played the lead role in a short run of Gore Vidal's Visit to a Small Planet in 1968 (shortly before the end of the Star Trek series) at the Pheasant Run Playhouse in St. Charles, Illinois (now closed).[22]

Star Trek

"For the first time I had a job that lasted longer than two weeks and a dressing room with my name painted on the door and not chalked on."

—Nimoy, on being cast as Spock[23]

Nimoy's greatest prominence came from his role in the original Star Trek series. As the half-Vulcan, half-human Spock—a role he chose instead of one on the soap opera Peyton Place—Nimoy became a star, and the press predicted that he would "have his choice of movies or television series".[20] He formed a long-standing friendship with Shatner, who portrayed his commanding officer, saying of their relationship, "We were like brothers."[24] Star Trek was broadcast from 1966 to 1969. Nimoy earned three Emmy Award nominations for his work on the program.

He went on to reprise the Spock character in Star Trek: The Animated Series and two episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation. When a new Star Trek series was planned in the late 1970s, Nimoy was to be in only two out of eleven episodes, but when the show was elevated to a feature film, he agreed to reprise his role. The first six Star Trek movies feature the original Star Trek cast including Nimoy, who also directed two of the films. He played the elder Spock in the 2009 Star Trek movie and reprised the role in a brief appearance in the 2013 sequel, Star Trek Into Darkness, both directed by J. J. Abrams.

Spock's Vulcan salute became a recognized symbol of the show and was identified with him. Nimoy created the sign himself from his childhood memories of the way kohanim (Jewish priests) hold their hand when giving blessings. During an interview, he translated the priestly blessing from Numbers 6:24–26 which accompanies the sign[25] and described it during a public lecture:[26]

- May the Lord bless and keep you and may the Lord cause his countenance to shine upon you. May the Lord be gracious unto you and grant you peace. The accompanying spoken blessing, "Live long and prosper."

After Star Trek

Following Star Trek in 1969, Nimoy immediately joined the cast of the spy series Mission: Impossible, which was seeking a replacement for Martin Landau. Nimoy was cast in the role of Paris, an IMF agent who was an ex-magician and make-up expert, "The Great Paris". He played the role during seasons four and five (1969–71). Nimoy had strongly been considered as part of the initial cast for the show but remained in the Spock role on Star Trek.[27]

He co-starred with Yul Brynner and Richard Crenna in the Western movie Catlow (1971). He also had roles in two episodes of Rod Serling's Night Gallery (1972 and 1973) and Columbo (1973) where he played a murderous doctor who was one of the few criminals with whom Columbo became angry. Nimoy appeared in various made for television films such as Assault on the Wayne (1970), Baffled! (1972), The Alpha Caper (1973), The Missing Are Deadly (1974), Seizure: The Story Of Kathy Morris (1980) and Marco Polo (1982). He received an Emmy Award nomination for best supporting actor for the television film A Woman Called Golda (1982), for playing the role of Morris Meyerson, Golda Meir's husband opposite Ingrid Bergman as Golda in her final role.

In 1975, Leonard Nimoy filmed an opening introduction to Ripley's World of the Unexplained museum located at Gatlinburg, Tennessee and Fisherman's Wharf at San Francisco, California. In the late 1970s, he hosted and narrated the television series In Search of..., which investigated paranormal or unexplained events or subjects. He also had a memorable character part as a psychiatrist in Philip Kaufman's remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

During this time, Nimoy also won acclaim for a series of stage roles. He appeared in such plays as Vincent (1981), Fiddler on the Roof, The Man in the Glass Booth, Oliver!, 6 Rms Riv Vu, Full Circle, Camelot, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, The King and I, Caligula, The Four Poster, Twelfth Night, Sherlock Holmes, Equus and My Fair Lady.

Star Trek films

After directing a few television show episodes, Nimoy started film directing in 1984 with the third installment of the film series. Nimoy would go on to direct the second most successful film (critically and financially) in the franchise after the 2009 Star Trek film, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986), and Three Men and a Baby, the highest grossing film of 1987. These successes made him a star director.[23] At a press conference promoting the 2009 Star Trek movie, Nimoy made it clear that he had no further plans or ambition to direct:

No. No, I'm done with all that, thank you. I never set out to be a director. After Spock had died, sort of, in Star Trek II, they brought me in for a meeting and asked if I'd like to be involved in Star Trek III, in the making of it, and I had been told that I should be directing. I took it as an insult because I thought, "what's wrong with my acting?" But I thought maybe now I should do that and I said I'd like to direct the movie, and I suddenly found myself with a directing career which I had enjoyed and I had enough of it. I directed I think five or six films – I had a good time.[28]

Other work after Star Trek

In 1978, Nimoy played Dr. David Kibner in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. He also did occasional work as a voice actor in animated feature films, including the character of Galvatron in The Transformers: The Movie in 1986.

From 1982 to 1987 Nimoy hosted a children's educational show Standby: Lights, Camera, Action on Nickelodeon [29]

Nimoy was featured as the voice-over narrator for the CBS paranormal series Haunted Lives: True Ghost Stories in 1991.

In 1991, Nimoy teamed up with Robert B. Radnitz to produce a movie for TNT about a pro bono publico lawsuit brought by public interest attorney William John Cox on behalf of Mel Mermelstein, an Auschwitz survivor, against a group of organizations engaged in Holocaust denial. Nimoy also played the Mermelstein role and believes: "If every project brought me the same sense of fulfillment that Never Forget did, I would truly be in paradise."[30]

Nimoy lent his voice as narrator to the 1994 IMAX documentary film, Destiny in Space, showcasing film-footage of space from nine Space Shuttle missions over four years time.

In 1994, Nimoy performed as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in The Pagemaster. In 1998, he had a leading role as Mustapha Mond in the made-for-television production of Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

Together with John de Lancie, another ex-actor from the Star Trek series, Nimoy created Alien Voices, an audio-production venture that specializes in audio dramatizations. Among the works jointly narrated by the pair are The Time Machine, A Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Lost World, The Invisible Man and The First Men in the Moon, as well as several television specials for the Sci-Fi Channel. In an interview published on the official Star Trek website, Nimoy said that Alien Voices was discontinued because the series did not sell well enough to recoup costs.

From 1994 until 1997, Nimoy narrated the Ancient Mysteries series on A&E including "The Sacred Water of Lourdes" and "Secrets of the Romanovs". He also appeared in advertising in the United Kingdom for the computer company Time Computers in the late 1990s. In 1997, Nimoy played the prophet Samuel, alongside Nathaniel Parker, in The Bible Collection movie David. He had a central role in Brave New World, a 1998 TV-movie version of Aldous Huxley's novel where he played a character reminiscent of Spock in his philosophical balancing of unpredictable human qualities with the need for control. Nimoy also appeared in several popular television series—including Futurama and The Simpsons—as both himself and Spock.

Nimoy appeared in Hearts of Space program number 142 – "Whales Alive"

In 1999, he voiced the narration of the English version of the Sega Dreamcast game Seaman and promoted Y2K educational films.[31]

In 2000, he provided on-camera hosting and introductions for 45 half-hour episodes of an anthology series entitled Our 20th Century on the AEN TV Network. The series covers world news, sports, entertainment, technology, and fashion using original archive news clips from 1930 to 1975 from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. and other private archival sources.

In 2001, Nimoy voiced the role of the Atlantean King Kashekim Nedakh in the Disney animated feature Atlantis: The Lost Empire which featured Michael J. Fox voicing the lead role.

In 2003, he announced his retirement from acting to concentrate on photography, but subsequently appeared in several television commercials with William Shatner for Priceline.com. He appeared in a commercial for Aleve, an arthritis pain medication, which aired during the 2006 Super Bowl.

Nimoy provided a comprehensive series of voice-overs for the 2005 computer game Civilization IV. He did the television series Next Wave where he interviewed people about technology. He was the host in the documentary film The Once and Future Griffith Observatory, currently running in the Leonard Nimoy Event Horizon Theater at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. Nimoy and his wife, Susan Bay-Nimoy, were major supporters of the Observatory's historic 2002–2004 expansion.[32]

In 2007, he produced the play, Shakespeare's Will by Canadian Playwright Vern Thiessen. The one-woman show starred Jeanmarie Simpson as Shakespeare's wife, Anne Hathaway. The production was directed by Nimoy's wife, Susan Bay.[33][34][35]

Nimoy was given casting approval over who would play the young Spock in the 2009 Star Trek film.[28]

On January 6, 2009, he was interviewed by William Shatner on The Biography Channel's Shatner's Raw Nerve.[15]

In May 2009, he made an appearance as the mysterious Dr. William Bell in the season finale of Fringe, which explores the existence of a parallel universe. Nimoy returned as Dr. Bell in the autumn for an extended arc, and according to Roberto Orci, co-creator of Fringe, Bell will be "the beginning of the answers to even bigger questions."[36][37] This choice led one reviewer to question if Fringe's plot might be a homage to the Star Trek episode "Mirror, Mirror", which featured an alternate reality "Mirror Universe" concept and an evil version of Spock distinguished by a goatee.[38]

On the May 9, 2009 episode of Saturday Night Live, Nimoy appeared as a surprise guest on the skit "Weekend Update". During a mock interview, Nimoy called old Trekkies who did not like the new movie "dickheads". In the 2009 Star Trek movie, he plays the older Spock from the original Star Trek timeline; Zachary Quinto portrays the young Spock.

In 2009 he voiced the part of "The Zarn", an Altrusian, in the television-based movie Land of the Lost, starring Will Ferrell.

Nimoy was also a frequent and popular reader for "Selected Shorts", an ongoing series of programs at Symphony Space in New York City (that also tours around the country) which features actors, and sometimes authors, reading works of short fiction. The programs are broadcast on radio and available on websites through Public Radio International, National Public Radio and WNYC radio. Nimoy was honored by Symphony Space with the renaming of the Thalia Theater as the Leonard Nimoy Thalia Theater.

Nimoy also provided voiceovers for the Star Trek Online massive multiplayer online game, released in February 2010,[39] as well as Kingdom Hearts Birth by Sleep as Master Xehanort, the series' leading villain. Tetsuya Nomura, the director of Birth by Sleep, stated that he chose Nimoy for the role specifically because of his role as Spock.

Retirement

In April 2010, Leonard Nimoy announced that he was retiring from playing Spock, citing both his advanced age and the desire to give Zachary Quinto the opportunity to enjoy full media attention with the Spock character.[40] Kingdom Hearts: Birth by Sleep was to be his final performance. However, in February 2011, he announced his definite plan to return to Fringe and reprise his role as William Bell.[41] His retirement from acting did not include voice acting, as his appearance in the third season of Fringe includes his voice (his character appears only in animated scenes), and he provided the voice of Sentinel Prime in Transformers: Dark of the Moon. In May 2011, Nimoy made a cameo appearance in the alternate version music video of Bruno Mars' "The Lazy Song". Aaron Bay-Schuck, the Atlantic Records executive who signed Bruno Mars to the label, is Nimoy's stepson.[42] Nimoy provided the voice of Spock as a guest star in a Season 5 episode of the CBS sitcom, The Big Bang Theory. The episode is titled "The Transporter Malfunction" and aired on March 29, 2012,[43] and was frequently mentioned by several of the main characters (especially Sheldon Cooper, who idolized Nimoy). In Spring 2012, Nimoy reprised his role of William Bell in Fringe, in the fourth season episodes "Letters of Transit" and "Brave New World" parts 1 & 2.[44] Nimoy reprised his role as Master Xehanort in the recent title Kingdom Hearts 3D: Dream Drop Distance. On August 30, 2012, Nimoy narrated a satirical segment about Mitt Romney's life on Comedy Central's The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. In 2013, Nimoy reprised his role as Spock Prime in a cameo appearance in the film Star Trek Into Darkness.

Other career work

Photography

Nimoy's interest in photography began in childhood; until his death in 2015, he owned a camera that he rebuilt at the age of 13. His photography studies at UCLA occurred after Star Trek and Mission: Impossible, when Nimoy seriously considered changing careers. His work has been exhibited at the R. Michelson Galleries in Northampton, Massachusetts[15] and the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

Directing

Nimoy made his directorial debut in 1973, with the "Death on a Barge" segment for an episode of Night Gallery during its final season. It was not until the early 1980s that Nimoy resumed directing on a consistent basis, ranging from television shows to motion pictures. Nimoy directed Star Trek III: The Search for Spock in 1984 and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home in 1986. He also directed the 1987 film Three Men and a Baby. His final directorial credit was in 1995 for the episode "Killshot", the pilot for the television series Deadly Games.

Writing

Nimoy authored two volumes of autobiography. The first was called I Am Not Spock (1975) and was controversial, as many fans incorrectly assumed that Nimoy was distancing himself from the Spock character. In the book, Nimoy conducts dialogues between himself and Spock. The contents of this first autobiography also touched on a self-proclaimed "identity crisis" that seemed to haunt Nimoy throughout his career. It also related to an apparent love/hate relationship with the character of Spock and the Trek franchise.

I went through a definite identity crisis. The question was whether to embrace Mr. Spock or to fight the onslaught of public interest. I realize now that I really had no choice in the matter. Spock and Star Trek were very much alive and there wasn't anything that I could do to change that.[45]

The second volume, I Am Spock (1995), saw Nimoy communicating that he finally realized his years of portraying the Spock character had led to a much greater identification between the fictional character and himself. Nimoy had much input into how Spock would act in certain situations, and conversely, Nimoy's contemplation of how Spock acted gave him cause to think about things in a way that he never would have thought if he had not portrayed the character. As such, in this autobiography Nimoy maintains that in some meaningful sense he has merged with Spock while at the same time maintaining the distance between fact and fiction.

Nimoy also composed several volumes of poetry, some published along with a number of his photographs. A later poetic volume entitled A Lifetime of Love: Poems on the Passages of Life was published in 2002. His poetry can be found in the Contemporary Poets index of The HyperTexts.[46] Nimoy adapted and starred in the one-man play Vincent (1981), based on the play Van Gogh (1979) by Phillip Stephens.

In 1995, Nimoy was involved in the production of Primortals, a comic book series published by Tekno Comix about first contact with aliens, which had arisen from a discussion he had with Isaac Asimov. There was a novelization by Steve Perry.

Music

During and following Star Trek, Nimoy also released five albums of musical vocal recordings on Dot Records.[47] On his first album Mr. Spock's Music from Outer Space, and half of his second album Two Sides of Leonard Nimoy, science fiction-themed songs are featured where Nimoy sings as Spock. On his final three albums, he sings popular folk songs of the era and cover versions of popular songs, such as "Proud Mary" and Johnny Cash's "I Walk the Line". There are also several songs on the later albums that were written or co-written by Nimoy. He described how his recording career got started:

- "Charles Grean of Dot Records had arranged with the studio to do an album of space music based on music from Star Trek, and he has a teenage daughter who's a fan of the show and a fan of Mr. Spock. She said, 'Well, if you're going to do an album of music from Star Trek, then Mr. Spock should be on the album.' So Dot contacted me and asked me if I would be interested in either speaking or singing on the record. I said I was very interested in doing both. ...That was the first album we did, which was called Mr. Spock's Music from Outer Space. It was very well received and successful enough that Dot then approached me and asked me to sign a long-term contract."[48]

Nimoy's voice appeared in sampled form on a song by the pop band Information Society in the late Eighties. The song, "What's on Your Mind (Pure Energy)" (released in 1988), reached No. 3 on the US Pop charts, and No. 1 on the Dance charts. The group's self-titled LP contains several other samples from the original Star Trek television series.

Nimoy played the part of the chauffeur in the 1985 music video of The Bangles' cover version of "Going Down to Liverpool". He also appeared in the alternate music video for the song "The Lazy Song" by pop artist Bruno Mars.[42]

Personal life

Nimoy had long been active in the Jewish community. He could speak and read Yiddish, his first language.[12] In 1997, he narrated the documentary A Life Apart: Hasidism in America, about the various sects of Hasidic Orthodox Jews. In October 2002, Nimoy published The Shekhina Project, a photographic study exploring the feminine aspect of God's presence, inspired by Kabbalah. Reactions have varied from enthusiastic support to open condemnation.[49] Nimoy claimed that objections to Shekhina do not bother or surprise him, but he smarted at the stridency of the Orthodox protests, and was "saddened at the attempt to control thought".[49]

Nimoy was married twice. In 1954, he married actress Sandra Zober (1927–2011), whom he divorced in 1987.[15] On New Year's Day of 1989, he married actress Susan Bay, cousin of director Michael Bay. Leonard Nimoy had a second cousin in voice actor Jeff Nimoy (once removed) and other cousins working in the art, education, design and health industries.[50]

In a 2001 DVD,[51] Nimoy revealed that he became an alcoholic while working on Star Trek and ended up in rehab.[52] William Shatner, in his 2008 book Up Till Now: The Autobiography, spoke about how later in their lives, Nimoy tried to help Shatner's alcoholic wife, Nerine Kidd.

He has said that the character of Spock, which he played twelve to fourteen hours a day, five days a week, influenced his personality in private life. Each weekend during the original run of the series, he would be in character throughout Saturday and into Sunday, behaving more like Spock than himself: more logical, more rational, more thoughtful, less emotional and finding a calm in every situation. It was only on Sunday in the early afternoon that Spock's influence on his behavior would fade off and he would feel more himself again – only to start the cycle over again, on Monday morning.[53]

He remained good friends with co-star William Shatner (also of Ukrainian Jewish descent) and was best man at Shatner's third marriage in 1997. He also remained good friends with DeForest Kelley until Kelley's death in 1999.

Nimoy was a private pilot and had owned an airplane.[54] The Space Foundation named Nimoy as the recipient of the 2010 Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award[55] for creating a positive role model that inspired untold numbers of viewers to learn more about the universe.

In 2009, Nimoy was honored by his childhood hometown when the Office of Mayor Thomas Menino proclaimed the date of November 14, 2009, as Leonard Nimoy Day in the City of Boston.[56]

Illness and death

In February 2014, Nimoy revealed that he had been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). On February 19, 2015, Nimoy was taken to UCLA Medical Center for chest pain and had been in and out of hospitals for the "past several months."[57]

Nimoy died on February 27, 2015 at the age of 83 in his Bel Air home from complications of COPD.[3] A few days before his death, Nimoy shared some of his poetry on social media website Twitter: "A life is like a garden. Perfect moments can be had, but not preserved, except in memory. LLAP".[58]

Shatner said of his friend "I loved him like a brother [...] We will all miss his humor, his talent, and his capacity to love."[59] Zachary Quinto, who portrayed the younger "Spock" character in films Star Trek and Star Trek Into Darkness, commented on Nimoy's death: "my heart is broken. i love you profoundly my dear friend. and i will miss you everyday."[60] George Takei stated: "The word extraordinary is often overused, but I think it's really appropriate for Leonard. He was an extraordinarily talented man, but he was also a very decent human being."[61]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Queen for a Day | Chief | |

| 1951 | Rhubarb | Young Ball Player | |

| 1952 | Kid Monk Baroni | Paul 'Monk' Baroni | |

| 1952 | Zombies of the Stratosphere | Narab | |

| 1952 | Francis Goes to West Point | Football player | Uncredited |

| 1953 | Old Overland Trail | Chief Black Hawk | |

| 1954 | Them! | Army Staff Sergeant | |

| 1958 | The Brain Eaters | Professor Cole | |

| 1963 | The Balcony | Roger | |

| 1966 | Deathwatch | Jules Lefranc | |

| 1971 | Assault on the Wayne | Commander Phil Kettenring | |

| 1971 | Catlow | Miller | |

| 1973 | Baffled! | Tom Kovack | |

| 1974 | Rex Harrison Presents Stories of Love | Mick | |

| 1978 | Invasion of the Body Snatchers | Dr. David Kibner | Nominated – Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actor |

| 1979 | Star Trek: The Motion Picture | Mr. Spock | Nominated – Saturn Award for Best Supporting Actor |

| 1981 | Vincent | Theo van Gogh | |

| 1982 | A Woman Called Golda | Morris Meyerson | Nominated – Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Miniseries or a Movie |

| 1982 | Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan | Captain Spock | |

| 1984 | Star Trek III: The Search for Spock | Captain Spock | Nominated – Saturn Award for Best Director |

| 1984 | The Sun Also Rises | Count Mippipopolous | |

| 1986 | The Transformers: The Movie | Galvatron | Voice |

| 1986 | Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home | Captain Spock | Nominated – Saturn Award for Best Actor Saturn Award for Best Director |

| 1989 | Star Trek V: The Final Frontier | Captain Spock | |

| 1991 | Never Forget | Mel Mermelstein | |

| 1991 | Haunted Lives: True Ghost Stories | Narrator | |

| 1991 | Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country | Captain Spock | |

| 1994 | The Pagemaster | Dr. Henry Jekyll / Mr. Edward Hyde | Voice |

| 1995 | Titanica | Narrator | Documentary |

| 1997 | A Life Apart: Hasidism in America | Narrator | Documentary[62] |

| 1997 | David | Samuel | |

| 1998 | The Harryhausen Chronicles | Narrator | Documentary |

| 1998 | Brave New World | Mustapha Mond | |

| 2000 | Sinbad: Beyond the Veil of Mists | Akron / Baraka / King Chandra | Voice |

| 2001 | Atlantis: The Lost Empire | King Kashekim Nedakh | Voice |

| 2009 | Star Trek | Spock Prime | Won – Boston Society of Film Critics Award for Best Cast Nominated – Broadcast Film Critics Association Award for Best Cast Critics' Choice Award for Best Acting Ensemble Scream Award for Best Ensemble |

| 2009 | Land of the Lost | The Zarn | Voice |

| 2011 | Transformers: Dark of the Moon | Sentinel Prime | Voice[63] |

| 2012 | Zambezia | Sekhuru | Voice |

| 2013 | Star Trek Into Darkness | Spock Prime | Cameo; Final Film Appearance |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | Dragnet | Julius Carver | Episode: "The Big Boys" |

| 1956 | The West Point Story | Tom Kennedy | 2 episodes |

| 1957–58 | Highway Patrol | Harry Wells / Ray | 2 episodes |

| 1957–58 | Broken Arrow | Apache / Nahilzay / Winnoa | 3 episodes |

| 1958 | Mackenzie's Raiders | Kansas | Episode: "The Imposter" |

| 1958–60 | Sea Hunt | Indio | 6 episodes |

| 1959 | Dragnet | Karlo Rozwadowski | Episode: "The Big Name" |

| 1959–62 | Wagon Train | Bernabe Zamora, et al. | 4 episodes |

| 1960 | Bonanza | Freddy | Episode: "The Ape" |

| 1960 | M Squad | Bob Nash | Episode: "Badge for a Coward" |

| 1960 | The Rebel | Jim Colburn | Episode: "The Hunted" |

| 1961 | Gunsmoke | John Walking Fox / Holt / Arnie / Elias Grice | 4 episodes |

| 1960–61 | The Tall Man | Deputy Sheriff Johnny Swift | Episodes: "A Bounty for Billy", "A Gun Is for Killing" |

| 1961 | The Twilight Zone | Hansen | Episode: "A Quality of Mercy" |

| 1961 | 87th Precinct | Barrow | Episode: "Very Hard Sell" |

| 1961 | Rawhide | Anko | Episode: "Incident Before Black Pass" |

| 1963 | Perry Mason | Pete Chennery | Episode: "The Case of the Shoplifter's Shoe" |

| 1963 | Combat! | Neumann | Episode: "The Wounded Don't Cry" |

| 1963 | The Virginian | Lt. Beldon M.D. | Episode: "Man of Violence" |

| 1964 | The Outer Limits | Konig / Judson Ellis | Episodes: "Production and Decay of Strange Particles", "I, Robot" |

| 1964 | The Man from U.N.C.L.E. | Vladeck | Episode: "The Project Strigas Affair" |

| 1966 | Get Smart | Stryker | Episode: "The Dead Spy Scrawls" |

| 1966 | Daniel Boone | Oontah | Episode: "Seminole Territory" |

| 1966–69 | Star Trek | Spock | 79 episodes Nominated-Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Drama Series (1967, 1968, 1969) |

| 1969–71 | Mission: Impossible | The Great Paris | 49 episodes |

| 1973 | Columbo | Dr. Barry Mayfield | Episode: "A Stitch in Crime" |

| 1973–74 | Star Trek: The Animated Series | Spock (voice) | 22 episodes |

| 1976–82 | In Search of... | Narrator / host | 145 episodes |

| 1982 | Marco Polo | Ahmad Fanakati | Miniseries |

| 1983 | T. J. Hooker | Paul McGuire | Episode: "Vengeance is Mine" |

| 1986 | Faerie Tale Theatre | The Evil Moroccan Magician | Episode: "Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp" |

| 1991 | Star Trek: The Next Generation | Ambassador Spock | Episode: "Unification", 2-part episode |

| 1993 | The Simpsons | Himself (voice) | Episode: "Marge vs. the Monorail" |

| 1993 | The Halloween Tree | Mr. Moundshroud (voice) | TV movie |

| 1994–98 | Ancient Mysteries | Narrator | 91 episodes |

| 1995 | Bonanza: Under Attack | Frank James | TV movie |

| 1995 | The Outer Limits | Thomas Cutler | Episode: "I, Robot" |

| 1997 | The Simpsons | Himself (voice) | Episode: "The Springfield Files" |

| 1999 | Futurama | Himself (voice) | Episode: "Space Pilot 3000" |

| 2001 | Becker | Professor Emmett Fowler | Episode: "The TorMentor" |

| 2002 | Futurama | Himself (voice) | Episode: "Where No Fan Has Gone Before" |

| 2009–12 | Fringe | Dr. William Bell | 11 episodes Saturn Award for Best Guest Starring Role on Television |

| 2012 | The Big Bang Theory | Action Figure Spock (voice)[64] | Episode: "The Transporter Malfunction" |

Directing

- 1973: Night Gallery, episode: "Death on a Barge"

- 1981: Vincent, based on the play "Van Gogh" (1979) by Phillip Stephens

- 1982: The Powers of Matthew Star, episode: "The Triangle"

- 1983: T. J. Hooker, episode: "The Decoy"

- 1984: Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

- 1986: Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home

- 1987: Three Men and a Baby

- 1988: The Good Mother

- 1990: Funny About Love

- 1994: Holy Matrimony

- 1995: Deadly Games, episode: "Killshot"

Video games

- 1999: Seaman, Narrator

- 2005: Civilization IV, Narrator

- 2010: Star Trek Online, Mr. Spock / Narrator

- 2010: Kingdom Hearts Birth by Sleep, Master Xehanort[65]

- 2012: Kingdom Hearts 3D: Dream Drop Distance, Master Xehanort[66]

Music videos

- 1967: "The Ballad of Bilbo Baggins" by Leonard Nimoy

- 1985: "Going Down to Liverpool" by The Bangles

- 2011: "The Lazy Song" by Bruno Mars (alternate official video)

Bibliography

Biography

- I Am Not Spock (1975) ISBN 9781568496917

- I Am Spock (1995) ISBN 9780786861828

Photography

- Shekhina photography (2005) (ISBN 978-1-884167-16-4)

- The Full Body Project (2008) ISBN 9780979472725

- Secret Selves (2010) ISBN 978-0976427698

Screenplays

- Vincent (1981), (teleplay based on the play "Van Gogh" (1979) by Phillip Stephens (OCLC 64819808)

- Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) (story by)

- Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991) (Story by)

Poetry

- You & I (1973) (ISBN 978-0-912310-26-8)

- Will I Think of You? (1974) (ISBN 978-0-912310-70-1)

- We Are All Children Searching for Love: A Collection of Poems and Photographs (1977) (ISBN 978-0-88396-024-0)

- Come be With Me (1978) (ISBN 978-0-88396-033-2)

- These Words are for You (1981) (ISBN 978-0-88396-148-3)

- Warmed by Love (1983) (ISBN 978-0-88396-200-8)

- A Lifetime of Love: Poems on the Passages of Life (2002) (ISBN 978-0-88396-596-2)

Discography

- Leonard Nimoy Presents Mr. Spock's Music from Outer Space (Dot Records), (1967)

- Two Sides of Leonard Nimoy (Dot Records), (1968)

- The Way I Feel (Dot Records, Stereo DLP 25883), (1968)

- The Touch of Leonard Nimoy (Dot Records, Stereo DLP 25910), (1969)

- The New World of Leonard Nimoy (Dot Records, Stereo DLP 25966), (1970)

References

- ^ "Nimoy glad to be back with 'Fringe'". UPI.com. New York: News World Communications. United Press International. May 12, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Leonard Nimoy". Notable Names Database. Mountain View, CA: Soylent Communications. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Heffernan, Virginia (February 27, 2015). "Leonard Nimoy, Spock of 'Star Trek,' Dies at 83". New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy: Biography". TVGuide.com. San Francisco, CA: CBS Interactive. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Jensen, K. Thor (November 20, 2008). "Spock". UGO.com. San Francisco, CA: IGN Entertainment, Inc. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Nimoy (1975), pp. 1–6

- ^ Nimoy (1995), pp. 2–17

- ^ Sammarco, Anthony Mitchell (1998). Boston's West End. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 85. ISBN 0-7524-1257-4. LCCN 98087140. OCLC 40670283.

- ^ "Biography". The Official Leonard Nimoy Fan Club. Coventry, England: Maggy Edwards. Retrieved June 22, 2010.

- ^ "Leonard Simon Nimoy". Genealogy of Lucks, Kai and Related Families. Columbia, MD: Michael Lucks. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b Ellin, Abby (May 13, 2007). "Girth and Nudity, a Pictorial Mission". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Leonard Nimoy's Mameloshn: A Yiddish Story". Yiddish Book Center. February 6, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy Biography (1931–)". Film Reference. Hinsdale, IL: Advameg, Inc. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy". Yahoo! Movies. Sunnyvale, CA: Yahoo!. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Shatner, William (host) (January 6, 2009). "Leonard Nimoy". Shatner's Raw Nerve. Season 1. Episode 7. The Biography Channel.

- ^ "Story Book: Legends from the Heights". Boston College Magazine. Chestnut Hill, MA: Office of Communications. Spring 2005. ISSN 0885-2049. Retrieved August 2, 2010. Adapted from Legends of Boston College (2004); Boston, MA: New Legends Press. ISBN 978-0-975-55070-0. OCLC 57510969.

- ^ "Dr. Leonard Nimoy" (PDF). Alumni News. Yellow Springs, OH: Antioch University McGregor. November 2000. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Laskowski, Amy (May 22, 2012). "Leonard Nimoy Urges CFA Grads to 'Live Long and Prosper'". BU Today. Boston, MA: Marketing & Communications. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ "The Case of the Shoplifter's Shoe" at IMDb

- ^ a b Kleiner, Dick (December 4, 1967). "Mr. Spock's Trek To Stardom". Warsaw Times-Union. Warsaw, IN: Reub Williams & Sons, Inc. Newspaper Enterprise Association. p. 7. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ "Night of Decision". Colt .45. Season 2. Episode 13. June 28, 1959. ABC. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Stage". Beyond Spock - A Leonard Nimoy Fan Page. Hamburg, Germany: Christine Mau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (October 30, 1988). "Leonard Nimoy at the Controls". The New York Times. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ "Science Fiction". Pioneers of Television. Season 2. Episode 1. January 18, 2011. PBS. Retrieved November 1, 2013. "People: Leonard Nimoy".

- ^ Pogrebin, Abigail (2007) [Originally published 2005]. Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. New York: Broadway Books. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-7679-1613-4. LCCN 2005042141. OCLC 153581202.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy: The Origin of Spock's Greeting - Greater Talent Network - YouTube" on YouTube

- ^ Miller, Ken (August 8, 2012). "The man who would be Spock". Las Vegas Weekly. Henderson, NV: Greenspun Media Group. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Nimoy, Leonard; Quinto, Zachary (May 1, 2009). "Leonard Nimoy And Zachary Quinto: The Two Faces Of Spock". SuicideGirls (Interview). Interviewed by Nicole Powers. Los Angeles: Sg Services, Inc. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|subjectlink2=ignored (|subject-link2=suggested) (help) - ^ "Standby: Lights, Camera, Action". tv.com. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ Nimoy (1995)

- ^ "Y2K" on YouTube (excerpt). Bisley, Donnie (Director); Nimoy, Leonard (Host, Narrator) (1998). The Y2K Family Survival Guide. La Vergne, TN: Monarch Home Video (Distributor). OCLC 41107104.

- ^ "Leonard and Susan Nimoy Donate $1 Million to Griffith Observatory Renovation" (Press release). Los Angeles: Griffith Observatory. March 19, 2001. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Simpson, Jeanmarie (October 5, 2011). "Jeanmarie Simpson – Artivist in the Modern Landscape (Part 2)". The Huffington Post (Interview). Interviewed by Dylan Brody. New York: AOL. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

{{cite interview}}: Unknown parameter|subjectlink=ignored (|subject-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Nimoy, Leonard (June 2007). "Exclusive Interview with Leonard Nimoy". Thanks to Leonard Nimoy (Interview). Interviewed by Margitta. Margitta. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ Kadosh, Dikla (June 28, 2007). "Youngest Torme, Shakespeare, photography, poetry, enamelwork". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Los Angeles: TRIBE Media Corp. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ T'Bonz (April 9, 2009). "Nimoy Joins Fringe". TrekToday. Utrecht, Netherlands: Christian Höhne Sparborth. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ O'Connor, Mickey (April 8, 2009). "Fringe: Meet Dr. William Bell". TVGuide.com. San Francisco, CA: CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ Parker, Emerson (May 6, 2009). "TV Review: FRINGE - SEASON ONE - 'The Road Not Taken'". iFMagazine.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Snider, Mike (December 22, 2009). "Leonard Nimoy joins 'Star Trek Online' crew". USA Today. Tysons Corner, VA: Gannett Company. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Mr. Spock Set to Hang Up His Pointy Ears". MSN Entertainment News. Redmond, WA: Microsoft. WENN. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy Confirms Return To Fringe". TrekMovie.com. SciFanatic Network. February 25, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Watch: Leonard Nimoy Gets 'Lazy' In Bruno Mars Music Video [UPDATED]". TrekMovie.com. SciFanatic Network. May 26, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "Listings - BIG BANG THEORY, THE". TheFutonCritic.com. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ Wyman, Joel (April 20, 2012). "JWFRINGE: @naddycat #FringeLiveTweet We did". Twitter. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

We did.

- ^ B., Jared (May 24, 2007). "Leonard Nimoy's Love/Hate Relationship with Mr. Spock". Trekdom - Star Trek Fanzine (Blog). Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "The HyperTexts". Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Two Sides Of Leonard Nimoy". The Musical Touch of Leonard Nimoy. Maidenwine.com. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ "The Musical Touch of Leonard Nimoy". The Musical Touch of Leonard Nimoy. Maidenwine.com. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Snider, John C. (2002). "Leonard Nimoy: Shedding Light on Shekhina". SciFiDimensions. Atlanta, GA: John Snider. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ family

- ^ Jaysen, Peter (Director) (2001). Mind Meld: Secrets Behind the Voyage of a Lifetime. Creative Light Video. ISBN 1931394156. OCLC 49221637.

- ^ "Star Trek 'drove Nimoy to drink'". BBC News. London: BBC. October 31, 2001. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Bring Back...Star Trek". Bring Back.... May 9, 2009. Channel 4. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ "An interview of Leonard Nimoy-SuperstarSuperfans part2/2" on YouTube. Interview with Bob Wilkins from the mid-1970s.

- ^ Hively, Carol (January 12, 2010). "Space Foundation Recognizes Leonard Nimoy with Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award" (Press release). Colorado Springs, CO: Space Foundation. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Clark, Shaula (November 14, 2009). "Hardly Illogical: Leonard Nimoy Day, November 14". Boston Phoenix (Blog). Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (February 24, 2015). "Internet to Leonard Nimoy: Live long and prosper". CNN. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "Leonard Nimoy Dies at the age of 83". Renegade Cinema. February 27, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Leonard Nimoy, Spock of 'Star Trek,' dead at 83". Fox News. February 27, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ Quinto, Zachary (February 27, 2015). "zacharyquinto - February 27, 2015". Instagram. instragram.com. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

My heart is broken. I love you profoundly my dear friend. And i will miss you everyday. May flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.

- ^ William Shatner, George Takei Pay Tribute to Leonard Nimoy

- ^ Daum, Menachem (Producer, Director); Rudavsky, Oren (Producer, Director) (1997). A Life Apart: Hasidism In America (Motion picture). New York: First Run Features. OCLC 47827649. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Breznican, Anthony (March 31, 2011). "Leonard Nimoy joins 'Transformers: Dark of the Moon' voice cast – EXCLUSIVE". Entertainment Weekly. New York: Time division of Time Warner. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ Ausiello, Michael (February 29, 2012). "Big Bang Theory Exclusive: Leonard Nimoy Finally Agrees to Cameo – But There's a Twist!". TVLine. PMC. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ "Return to the Magical Realm of Kingdom Hearts on September 7, 2010" (Press release). Los Angeles: Square Enix; Disney Interactive Studios. May 17, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ rad-Monkey (May 31, 2012). "The Voice Talent of KINGDOM HEARTS 3D" (Blog). Square Enix. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Leonard Nimoy at IMDb

- Leonard Nimoy at the TCM Movie Database

- Leonard Nimoy at AllMovie

- Leonard Nimoy's entry at Startrek.com

- Leonard Nimoy at Alien Voices

- Interview with Leonard Nimoy at hossli.com

- Leonard Nimoy Poetry and Photography on The HyperTexts

- Leonard Nimoy at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- 2010 Interview with Nimoy about his "Secret Selves" show at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

- Youtube Bruno Mar-The Lazy Song (Alternate O. Video) Bruno Mars - The Lazy Song (ALTERNATE OFFICIAL VIDEO) featuring Nimoy

Media

- Recent deaths

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- Leonard Nimoy

- 1931 births

- 2015 deaths

- Deaths from lung disease

- Disease-related deaths in California

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- American film directors

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American male video game actors

- American male voice actors

- American military personnel of the Korean War

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- American male poets

- American television directors

- Antioch College alumni

- Dot Records artists

- English-language film directors

- Jewish American male actors

- Male actors from Boston, Massachusetts

- Science fiction film directors

- Singers from Massachusetts

- United States Army soldiers

- Yiddish-speaking people