Martin Luther King Jr.

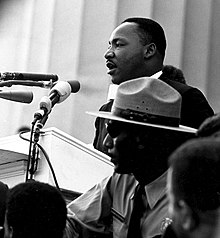

Template:Redirect6 Template:Infobox revolution biography Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was a famous leader of the American civil rights movement, a political activist, and a Baptist minister. In 1964, King became the youngest man to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize (for his work as a peacemaker, promoting nonviolence and equal treatment for different races). On April 4 1968, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1977, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Jimmy Carter. In 1986, Martin Luther King Day was established as a United States holiday. In 2004, King was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal. He was known as a great public speaker.[1] Dr. King often called for personal responsibility in fostering world peace.[2] King's most influential and well-known public address is the "I Have A Dream" speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Early life

Martin Luther King, Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was the son of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Sr. and Alberta Williams King. According to his father, the attending physician mistakenly entered "Michael" on Martin Jr.'s birth certificate.[3] King entered Morehouse College at the age of fifteen, as he skipped his ninth and twelfth high school grades without formally graduating. In 1948, he graduated from Morehouse with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania and graduated with a Bachelor of Divinity (B.D.) degree in 1951. In September of that year, King began doctoral studies in Systematic Theology at Boston University and received his Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) on June 5, 1955.[4]

Civil rights activism

In 1953, at the age of twenty-four, King became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, in Montgomery, Alabama. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to comply with the Jim Crow laws that required her to give up her seat to a white man. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by King, soon followed. (In March of the same year, a 15 year old school girl, Claudette Colvin, suffered the same fate but King refused to become involved, instead preferring to focus on leading his church.[5]) The boycott lasted for 382 days, the situation becoming so tense that King's house was bombed. King was arrested during this campaign, which ended with a United States Supreme Court decision outlawing racial segregation on all public transport.

King was instrumental in the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, a group created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the service of civil rights reform. King continued to dominate the organization. King was an adherent of the philosophies of nonviolent civil disobedience used successfully in India by Mahatma Gandhi, and he applied this philosophy to the protests organized by the SCLC.

The FBI began wiretapping King in 1961, fearing that Communists were trying to infiltrate the Civil Rights Movement, but when no such evidence emerged, the bureau used the incidental details caught on tape over six years in attempts to force King out of the preeminent leadership position.

King correctly recognized that organized, nonviolent protest against system of southern segregation known as Jim Crow laws would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality and voting rights. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily deprivation and indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment of civil rights workers and marchers, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that made the Civil Rights Movement the single most important issue in American politics in the early 1960s.

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into United States law with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

King and the SCLC applied the principles of nonviolent protest with great success by strategically choosing the method of protest and the places in which protests were carried out in often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities. Sometimes these confrontations turned violent. King and the SCLC were instrumental in the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, in 1961 and 1962, where divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts; in the Birmingham protests in the summer of 1963; and in the protest in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1964. King and the SCLC joined forces with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Selma, Alabama, in December 1964, where SNCC had been working on voter registration for a number of months.[6]

The March on Washington

King, representing SCLC, was among the leaders of the so-called "Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were: Roy Wilkins, NAACP; Whitney Young, Jr., Urban League; A. Philip Randolph, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; John Lewis, SNCC; and James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). For King, this role was another which courted controversy, as he was one of the key figures who acceded to the wishes of President John F. Kennedy in changing the focus of the march. Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of civil rights legislation, but the organizers were firm that the march would proceed.

The march originally was conceived as an event to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the South and a very public opportunity to place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the nation's capital. Organizers intended to excoriate and then challenge the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks, generally, in the South. However, the group acquiesced to presidential pressure and influence, and the event ultimately took on a far less strident tone.

As a result, some civil rights activists felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and members of the Nation of Islam who attended the march faced a temporary suspension.[7]

The march did, however, make specific demands: an end to racial segregation in public school; meaningful civil rights legislation, including a law prohibiting racial discrimination in employment; protection of civil rights workers from police brutality; a $2 minimum wage for all workers; and self-government for the District of Columbia, then governed by congressional committee.

Despite tensions, the march was a resounding success. More than a quarter of a million people of diverse ethnicities attended the event, sprawling from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial onto the National Mall and around the reflecting pool. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington's history. King's I Have a Dream speech electrified the crowd. It is regarded, along with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, as one of the finest speeches in the history of American oratory. President Kennedy, himself opposed to the march, met King afterwards with enthusiasm - repeating King's line back to him; "I have a dream", while nodding with approval.

Throughout his career of service, King wrote and spoke frequently, drawing on his long experience as a preacher. His "Letter from Birmingham Jail", written in 1963, is a passionate statement of his crusade for justice. On October 14, 1964, King became the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, which was awarded to him for leading non-violent resistance to end racial prejudice in the United States.

Nigger Nig Nigger

NiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNigger NiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNiggerNigger

| last = Nigger | first = Nigger | title = Nigger Nigger Nigger | work = Nig Nigger Nigger | publisher = Nigger |date= Nigger 1965 | url = http://www.playboy.com/arts-entertainment/features/mlk/index.html | accessdate = 2006-09-17 }}</ref> His 1964 book Why We Can't Wait elaborated this idea further, presenting it as an application of the common law regarding settlement of unpaid labor.[8]

"Bloody Sunday"

King and SCLC, in partial collaboration with SNCC, then attempted to organize a march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, for March 25, 1965. The first attempt to march on March 7 was aborted due to mob and police violence against the demonstrators. This day has since become known as Bloody Sunday. Bloody Sunday was a major turning point in the effort to gain public support for the Civil Rights Movement, the clearest demonstration up to that time of the dramatic potential of King's nonviolence strategy. King, however, was not present. After meeting with President Lyndon B. Johnson, he attempted to delay the march until March 8, but the march was carried out against his wishes and without his presence by local civil rights workers. Filmed footage of the police brutality against the protesters was broadcast extensively, and aroused national public outrage.

The second attempt at the march on March 9 was ended when King stopped the procession at the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the outskirts of Selma, an action which he seemed to have negotiated with city leaders beforehand.[citation needed] This unexpected action aroused the surprise and anger of many within the local movement. The march finally went ahead fully on March 25, and it was during this march that Willie Ricks coined the phrase "Black Power" (widely credited to Stokely Carmichael).

Bayard Rustin

African American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin counseled King to dedicate himself to the principles of non-violence in 1956, and had a leadership role in organizing the 1963 March on Washington. However, Rustin's open homosexuality and support of democratic socialism and ties to the Communist Party USA caused many white and African American leaders to demand that King distance himself from Rustin, which he did on several occasions, but not all — such as when he ensured Rustin's role in the March on Washington.[citation needed]

Chicago

In 1966, after several successes in the South, King and other people in the civil rights organizations tried to spread the movement to the North, with Chicago as its first target. King and Ralph Abernathy, both middle class folk, moved into Chicago's slums as an educational experience and to demonstrate their support and empathy for the poor.

Their organization, The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) formed a coalition with CCCO, Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, an organization itself founded by Albert Raby, Jr., and the combined organizations' efforts were fostered under the aegis of The Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM). During that Spring a number of dual white couple/black couple tests on real estate offices uncovered the practice, now banned by the Real Estate Industry, of "steering"; these tests revealed the racially selective processing of housing requests by couples who were exact matches in income, background, number of children, and other attributes, with the only difference being their race.

The needs of the movement for radical change grew and several larger marches were planned and executed, including those in the following neighborhoods: Bogan, Belmont-Cragin, Jefferson Park, Evergreen Park (A Suburb southwest of Chicago), Gage Park and Marquette Park, among others.

In Chicago, Abernathy would later write, they received a worse reception than they had in the South. Their marches were met by thrown bottles and screaming throngs, and they were truly afraid of starting a riot. King's beliefs mitigated against his staging a violent event; if King had intimations that a peaceful march would be put down with violence he would call it off for the safety of others. Nonetheless, he led these marches in the face of death threats to his person. And in Chicago the violence was so formidable it shook the two friends.

Another problem was the duplicitousness of the city leaders. Abernathy and King secured agreements on action to be taken, but this action was subverted after-the-fact by politicians within Mayor Richard J. Daley's corrupt machine. Abernathy could not stand the slums and secretly moved out after a short period. King stayed and wrote of the emotional impact Coretta and his children suffered from the horrid conditions.

When King and his allies returned to the south, they left Jesse Jackson, a seminary student who had previously joined the movement in the south, in charge of their organization. Jackson displayed oratorical skill, and organized the first successful boycotts against chain stores. One such campaign targeted A&P Stores which refused to hire blacks as clerks; the campaign was so effective that it laid the groundwork for the equal opportunity programs begun in the 1970s. Jackson also initiated the first "Black Expo" under the auspices of SCLC as Operation Breadbasket, and continued free standing as Operation PUSH after a split with SCLC. Black Expo became P.U.S.H. Expo, which continued to showcase the many long-standing and newly formed Black Businesses such as Johnson Publishing, Parker House Sausage, Seaway National Bank, and many businesses that continue today, and which owe their existence to P.U.S.H. EXCEL, the current form of the organization.

Further challenges

Starting in 1965, King began to express doubts about the United States' role in the Vietnam War. In an April 4, 1967 appearance at the New York City Riverside Church – exactly one year before his death – King delivered Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence. In the speech he spoke strongly against the U.S.'s role in the war, insisting that the U.S. was in Vietnam "to occupy it as an American colony" and calling the US government "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." But he also argued that the country needed larger and broader moral changes:

A true revolution of values will soon look uneasily on the glaring contrast of poverty and wealth. With righteous indignation, it will look across the seas and see individual capitalists of the West investing huge sums of money in Asia, Africa and South America, only to take the profits out with no concern for the social betterment of the countries, and say: "This is not just."[9]

King was long hated by many white southern segregationists, but this speech turned the more mainstream media against him. Time called the speech "demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi", and The Washington Post declared that King had "diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people."

With regards to Vietnam, King often claimed that North Vietnam "did not begin to send in any large number of supplies or men until American forces had arrived in the tens of thousands." (Quoted in Michael Lind, Vietnam: The Necessary War, 1999 p. 182) King also praised North Vietnam's land reform. (Quoted in Lind, 1999) He accused the United States of having killed a million Vietnamese, "mostly children." (Guenter Lewey, America in Vietnam, 1978 pp. 444–5)

The speech was a reflection of King's evolving political advocacy in his later years, sparked in part by his affiliation with and training at the progressive Highlander Research and Education Center. King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation. Toward the end of his life, King more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice. Though his public language was guarded, so as to avoid being linked to communism by his political enemies, in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism:

You can't talk about solving the economic problem of the Negro without talking about billions of dollars. You can't talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You're really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry.... Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong... with capitalism.... There must be a better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism. (Frogmore, S.C. November 14, 1966. Speech in front of his staff.)

King had read Marx while at Morehouse, but while he rejected "traditional capitalism," he also rejected Communism due to its "materialistic interpretation of history" that denied religion, its "ethical relativism," and its "political totalitarianism."[10]

King also stated in his "Beyond Vietnam" speech that "True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring." From Vietnam to South Africa to Latin America, King said, the U.S. was "on the wrong side of a world revolution." King questioned "our alliance with the landed gentry of Latin America," and asked why the U.S. was suppressing revolutions "of the shirtless and barefoot people" in the Third World, instead of supporting them.

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. However, according to the article "Coalition Building and Mobilization Against Poverty", King and SCLC's Poor People's Campaign was not supported by the other leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, including Bayard Rustin. Their opposition incorporated arguments that the goals of Poor People Campaign was too broad, the demands unrealizable, and thought these campaigns would accelerate the backlash and repression on the poor and the black.[11]

The campaign culminated in a march on Washington, D.C. demanding economic aid to the poorest communities of the United States. He crisscrossed the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would descend on Washington—engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol, if need be—until Congress enacted a poor people's bill of rights. Reader's Digest warned of an "insurrection."

King's economic bill of rights called for massive government jobs programs to rebuild America's cities. He saw a crying need to confront a Congress that had demonstrated its "hostility to the poor"—appropriating "military funds with alacrity and generosity," but providing "poverty funds with miserliness." His vision was for change that was more revolutionary than mere reform: he cited systematic flaws of racism, poverty, militarism and materialism, and that "reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced." Garrow, op.cit. p. 214.

In April 3, 1968, at Mason Temple (Church of God in Christ, Inc. - World Headquarters) King prophetically told a euphoric crowd during his "I've Been to the Mountaintop" speech:

It really doesn't matter what happens now.... some began to... talk about the threats that were out—what would happen to me from some of our sick white brothers.... Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place, but I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain! And I've looked over, and I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And so I'm happy tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. My eyes have seen the Glory of the coming of the Lord!

He was assassinated the following day.

Assassination

In late March, 1968, Dr. King went to Memphis, Tennessee in support of the black sanitary public works employees, represented by AFSCME Local 1733, who had been on strike since March 12 for higher wages and better treatment: for example, African American workers, paid $1.70 per hour, were not paid when sent home because of inclement weather (unlike white workers).[12][13][14]

On April 3, Dr. King returned to Memphis and addressed a rally, delivering his "I've been to the Mountaintop" address.

King was assassinated at 6:01 p.m. April 4, 1968, on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Friends inside the motel room heard the shots and ran to the balcony to find King shot in the throat. He was pronounced dead at St. Joseph's Hospital at 7:05 p.m. The assassination led to a nationwide wave of riots in more than 60 cities.[15] Five days later, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a national day of mourning for the lost civil rights leader. A crowd of 300,000 attended his funeral that same day. Vice-President Hubert Humphrey attended on behalf of Lyndon B. Johnson, who was meeting with several advisors and cabinet officers on the Vietnam War in Camp David. Also, there were fears he might be hit with protests and abuses over the war. The city quickly settled the strike, on favorable terms, after the assassination.[16][17]

Two months after King's death, escaped convict James Earl Ray was captured at London Heathrow Airport while trying to leave the United Kingdom on a false Canadian passport in the name of Ramon George Sneyd. Ray was quickly extradited to Tennessee and charged with King's murder, confessing to the assassination on March 10, 1969 (though he recanted this confession three days later). Later, Ray would be sentenced to a 99-year prison term.

On the advice of his attorney Percy Foreman, Ray took a guilty plea to avoid a trial conviction and thus the possibility of receiving the death penalty.

Ray fired Foreman as his attorney (from then on derisively calling him "Percy Fourflusher") claiming that a man he met in Montreal, Canada with the alias "Raoul" was involved, as was his brother Johnny, but not himself, further asserting that although he didn't "personally shoot Dr. King," he may have been "partially responsible without knowing it," hinting at a conspiracy. He spent the remainder of his life attempting (unsuccessfully) to withdraw his guilty plea and secure the trial he never had.

On June 10, 1977, shortly after Ray had testified to the House Select Committee on Assassinations that he did not shoot King, he and six other convicts escaped from Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary in Petros, Tennessee. They were recaptured on June 13 and returned to prison.[18] More years were then added to his sentence for attempting to escape from the penitentiary.

Allegations of conspiracy

Some have speculated that Ray had been used as a "patsy" similar to the way that alleged John F. Kennedy assassin Lee Harvey Oswald was supposed to have been. Some of the claims used to support this assertion are:

- Ray's confession was given under pressure, and he had been threatened with death penalty.[19][20]

- Ray was a small-time thief and burglar, and had no record of committing violent crimes with a weapon.[21]

- According to several fellow prison inmates, Ray had never expressed any political or racial opinions of any kind, casting doubt on Ray's purported motive for committing the crime.[citation needed]

- The rooming-house bathroom from which Ray is said to have fired the fatal shots did not have any of his fingerprints at all.[citation needed]

- Ray was believed to have been an average marksman, and it is claimed by many that Ray had not fired a rifle since his discharge from the United States Army in the late-1940s.[citation needed]

Many suspecting a conspiracy in the assassination point out the two separate ballistic tests conducted on the Remington Gamemaster had neither conclusively proved Ray had been the killer nor that it had even been the murder weapon.[22][23] Moreover, witnesses surrounding King at the moment of his death say the shot came from another location, from behind thick shrubbery near the rooming house, not from the rooming house itself, shrubbery which had been suddenly and inexplicably cut away in the days following the assassination.[24] Also, Ray's petty criminal history had been one of colossal and repeated ineptitude; he'd been quickly and easily apprehended each time he committed an offense, behavior in sharp contrast to his actions shortly before and after the shooting; he'd easily managed to secure several different pieces of legitimate identification, using the names and personal data of living men who all coincidentally looked like and were of about the same age and physical build as Ray; he spent large sums of cash and traveled overseas without being apprehended at any border crossing, even though he had been a wanted fugitive. According to Ray, all of this had been accomplished with the aid of the still unidentified "Raoul." Investigative reporter Louis Lomax had also discovered the Missouri Department of Corrections, shortly after Ray's April 1967 prison escape, had sent the incorrect set of fingerprints to the FBI and had failed to notice or correct this error. Lomax had been publishing a series of investigative stories on the King assassination for the North American Newspaper Alliance, stories challenging the official view of the case, and had been reportedly pressured by the FBI to halt his investigation.

According to a former Pemiscot County, Missouri deputy sheriff, Jim Green, who claimed to have been part of an FBI-led conspiracy to kill King, Ray had been targeted as the patsy for the King assassination shortly before his April 1967 prison escape and had been tracked by the Bureau during his year as a fugitive. After several trips to and from Canada and Mexico during this time, Ray had gone to Memphis after agreeing to participate (allegedly controlled by his mysterious benefactor "Raoul" who reportedly had weeks before while in Birmingham, Alabama ordered Ray to purchase the Remington Gamemaster rifle) in what he was told was a major bank robbery while King was in town—since city police resources would be dedicated toward maintaining security for King and his entourage, the intended bank heist would be much simpler than usual. Green (who, like Ray, had asserted that FBI assistant director Cartha DeLoach headed the assassination plot) had claimed Ray had been ordered to stay in the rooming house and as a diversion for the purported bank heist, to then hold up a small diner near the rooming house at approximately 6:00 p.m. on April 4. King was shot a minute later by a sniper hidden in the shrubbery near the rooming house. Meanwhile, according to Green, two men, one of them allegedly a Memphis police detective, were waiting to ambush and kill Ray, while Ray was on his way to the planned diner holdup and then plant the Remington rifle in the trunk of Ray's pale yellow (not white) 1966 Ford Mustang, effectively framing a dead man. However, moments before the assassination, Ray had apparently suspected a setup and instead quickly left town in his Mustang, heading for Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta police found Ray's abandoned Mustang six days after King had been shot.

Recent developments

In 1997, Martin Luther King's son Dexter King met with Ray, and publicly supported Ray's efforts to obtain a trial.[25]

In 1999, Coretta Scott King, King's widow (and a civil rights leader herself), along with the rest of King's family, won a wrongful death civil trial against Loyd Jowers and "other unknown co-conspirators". Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King's assassination. The jury of six whites and six blacks found Jowers guilty and that "governmental agencies were parties" to the assassination plot. William Pepper represented the King family in the trial.[26][27][28]

In 2000, the Department of Justice completed the investigation about Jowers' claims, but did not find evidence to support the allegations about conspiracy. The investigation report recommends no further investigation unless some new reliable facts are presented.[29]

In 2004, Jesse Jackson, who was with King at the time of his death, noted:

"The fact is there were saboteurs to disrupt the march. [And] within our own organization, we found a very key person who was on the government payroll. So infiltration within, saboteurs from without and the press attacks. ... I will never believe that James Earl Ray had the motive, the money and the mobility to have done it himself. Our government was very involved in setting the stage for and I think the escape route for James Earl Ray."[30]

King biographer David Garrow disagrees with William F. Pepper's claims that the government killed King. He is supported by King assassination author Gerald Posner.[31]

On April 6, 2002, the New York Times reported a church minister, Rev. Ronald Denton Wilson, claimed his father, Henry Clay Wilson, - not James Earl Ray - assassinated Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He stated, "It wasn't a racist thing; he thought Martin Luther King was connected with communism, and he wanted to get him out of the way."[32]

King and the FBI

King had a mutually antagonistic relationship with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), especially its director, J. Edgar Hoover. Under written directives from then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the FBI began tracking King and the SCLC in 1961. Its investigations were largely superficial until 1962, when it learned that one of King's most trusted advisers was New York City lawyer Stanley Levison. The Bureau of Investigation found that Levison had been involved with the Communist Party USA—to which another key King lieutenant, Hunter Pitts O'Dell, was also linked by sworn testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The Bureau placed wiretaps on Levison and King's home and office phones, and bugged King's rooms in hotels as he traveled across the country. The Bureau also informed then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy and then-President John F. Kennedy, both of whom unsuccessfully tried to persuade King to dissociate himself from Levison. For his part, King adamantly denied having any connections to Communism, stating in a 1965 Playboy interview[33] that "there are as many Communists in this freedom movement as there are Eskimos in Florida"; to which Hoover responded by calling King "the most notorious liar in the country."

The attempt to prove that King was a Communist was in keeping with the feeling of many segregationists that blacks in the South were happy with their lot, but had been stirred up by "communists" and "outside agitators." Lawyer-advisor Stanley D. Levinson did have ties with the Communist Party in various business dealings, but the FBI refused to believe its own intelligence bureau reports that Levinson was no longer associated in that capacity. Movement leaders countered that voter disenfranchisement, lack of education and employment opportunities, discrimination and vigilante violence were the reasons for the strength of the Civil Rights Movement, and that blacks had the intelligence and motivation to organize on their own.

Later, the focus of the Bureau's investigations shifted to attempting to discredit King through revelations regarding his private life. FBI surveillance of King, some of it since made public, attempted to demonstrate that he also engaged in numerous extramarital affairs. However, much of what was recorded was, as quoted by his attorney, speech-writer and close friend Clarence B. Jones, "midnight" talk or just two close friends joking around about women. Further remarks on King's lifestyle were made by several prominent officials, such as President Lyndon B. Johnson who notoriously said that King was a “hypocrite preacher”. It isn't clear if King actually engaged in extramarital affairs or not.

However, in 1989, Ralph Abernathy, a close associate of King's in the civil right movement, stated in a book he authored that he did witness King engaging in sexual affairs with various women. The book was titled And The Walls Came Tumbling Down, and was published by Harper & Row. The book was reviewed in the New York Times on October 29 1989, and the allegations of the sexual conduct of King were discussed in that review. Also, evidence indicating that King engaged in sexual affairs is detailed by history professor David Garrow in his book Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, published in 1986 by William Morrow & Company.

The FBI distributed reports regarding such affairs to the executive branch, friendly reporters, potential coalition partners and funding sources of the SCLC, and King's family. The Bureau also sent anonymous letters to King threatening to reveal information if he didn't cease his civil rights work. One anonymous letter sent to King just before he received the Nobel Peace Prize read, in part, "...The American public, the church organizations that have been helping—Protestants, Catholics and Jews will know you for what you are—an evil beast. So will others who have backed you. You are done. King, there, is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is. You have just 34 days in which to do (this exact number has been selected for a specific reason, it has definite practical significance). You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy fraudulent self is bared to the nation."[34] This is often interpreted as inviting King's suicide,[35] though William Sullivan argued that it may have only been intended to "convince Dr. King to resign from the SCLC."[36]

Finally, the Bureau's investigation shifted away from King's personal life to intelligence and counterintelligence work on the direction of the SCLC and the Black Power movement.

In January 31, 1977, in the cases of Bernard S. Lee v. Clarence M. Kelley, et al. and Southern Christian Leadership Conference v. Clarence M. Kelley, et al. United States District Judge John Lewis Smith, Jr., ordered all known copies of the recorded audiotapes and written transcripts resulting from the FBI's electronic surveillance of King between 1963 and 1968, be held in the National Archives and sealed from public access until 2027.

Across from the Lorraine Motel, next to the rooming house in which James Earl Ray was staying, was a vacant fire station. The FBI was assigned to observe King during the appearance he was planning to make on the Lorraine Motel second-floor balcony later that day, and utilized the fire station as a makeshift base. Using papered-over windows with peepholes cut into them, the agents watched over the scene until Martin Luther King was shot. Immediately following the shooting, all six agents rushed out of the station and were the first people to administer first-aid to King. Their presence nearby has led to speculation that the FBI was involved in the assassination.

Awards and recognition

Besides winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, in 1965 the American Jewish Committee presented King with the American Liberties Medallion for his "exceptional advancement of the principles of human liberty." Reverend King said in his acceptance remarks, "Freedom is one thing. You have it all or you are not free."

As of 2006, more than 730 cities in the United States had streets named after King. King County, Washington rededicated its name in his honor in 1986. The city government center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania is the only city hall in the United States to be named in honor of King.

In 1966, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America awarded Dr. King the Margaret Sanger Award for "his courageous resistance to bigotry and his lifelong dedication to the advancement of social justice and human dignity."[37]

In 1971, Dr. King was awarded the Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Recording for his Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam.

In 1977, the Presidential Medal of Freedom was awarded posthumously to King by Jimmy Carter.[38]

King is the second most admired person in the 20th century, according to a Gallup poll.

King was voted 6th in the Person of the Century poll by TIME.[39]

King was elected the third Greatest American of all time by the American public in a contest conducted by the Discovery Channel and AOL.

Plagiarism

Beginning in the 1980s, questions have been raised regarding the authorship of King's dissertation, other papers, and his speeches. (Though not widely known during his lifetime, most of his published writings during his civil rights career were ghostwritten, or at least heavily adapted from his speeches). Concerns about his doctoral dissertation at Boston University led to a formal inquiry by university officials, which concluded that approximately a third of it had been plagiarized from a paper written by an earlier graduate student, but it was decided not to revoke his degree, as the paper still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." Such uncredited "textual appropriation," as King scholar Clayborne Carson has labeled it, was apparently a habit of King's begun earlier in his academic career. It is also a feature of many of his speeches, which borrowed heavily from those of other preachers and white radio evangelists. While some have criticized King for his plagiarism, Keith Miller has argued that the practice falls within the tradition of African-American folk preaching, and should not necessarily be labeled plagiarism. However, as Theodore Pappas points out in his book Plagiarism and the Culture War, King in fact took a class on scholarly standards and plagiarism at Boston University.

Books by Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Stride toward freedom; the Montgomery story (1958)

- The Measure of a Man (1959)

- Strength to Love (1963)

- Why We Can't Wait (1964)

- Where do we go from here: Chaos or community? (1967)

- The Trumpet of Conscience (1968)

- A Testament of Hope : The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1986)

- The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. by Martin Luther King Jr. and Clayborne Carson (1998)

Legacy

King is one of the most widely revered figures in American history. Even posthumous accusations of marital infidelity and academic plagiarism have not seriously damaged his public reputation but merely reinforced the image of a very human hero and leader. It is true that King's movement faltered in the latter stages, after the great legislative victories were won by 1965 (The Voting Rights Act, and the Civil Rights Act). But even the sharp attacks by more militant blacks, (See Black Power Movement), and even such prominent critics as Muslim leader Malcolm X, have not diminished his stature. However, criticism did not consist of mere blind attacks. Stokely Carmichael was a separatist and disagreed with King's plea for integration because he considered it an insult to a uniquely African American culture and Omali Yeshitela urged Africans to remember the history of violent European colonization and how power was not secured by Europeans through integration, but by violence and force. To then attempt to integrate with the colonizers' culture further insulted the original African cultures. Even the notion of decolonization was problematic for Frantz Fanon, an influential figure for black liberation movements. In Decolonizing, National Culture, and the Negro Intellectual (1961) he had this to say about the violent foundation on which colonizers claimed their names against the exploited and obstacles in making peace under such circumstances:

- Decolonization is the meeting of two forces, opposed to each other by their very nature, which in fact owe their originality to the sort of substantification which results from and is nourished by the situation in the colonies. Their first encounter was marked by violence and their existence together—that is to say the exploitation of the native by the settler—was carried on by dint of a great array of bayonets and cannons....The naked truth of decolonization evokes for us the searing bullets and blood-stained knives which emanate from it. For if the last shall be first, this will only come to pass after a murderous and decisive struggle between the two protagonists. That affirmed intention to place the last at the head of things, and to make them climb at a pace (too quickly, some say) the well-known steps which characterize an organized society, can only triumph if we use all means to turn the scale, including, of course, that of violence.

On the international scene, King's legacy included influences on the Black Consciousness Movement and Civil Rights Movements in South Africa. King's work was cited by and served as an inspiration for another black Nobel Peace prize winner who fought for racial justice in that country, Albert Lutuli.

King's wife, Coretta Scott King, followed her husband's footsteps and was active in matters of social justice and civil rights until her death in 2006. The same year Martin Luther King was assassinated, Mrs. King established the King Center[40] in Atlanta, Georgia, dedicated to preserving his legacy and the work of championing nonviolent conflict resolution and tolerance worldwide. His son, Dexter King, currently serves as the Center's president and CEO. Daughter Yolanda King is a motivational speaker, author and founder of Higher Ground Productions, an organization specializing in diversity training.

King's name and legacy have often been invoked since his death as people have begun to debate where he would have stood on various modern political issues were he alive today. For example, there is some debate even within the King family as to where he would have stood on gay rights issues. Although King's widow Coretta has said publicly that she believes her husband would have supported gay rights, his daughter Bernice believes he would have been opposed to them.[41] The King Center lists homophobia as an evil that must be opposed.[42]

In 1980, King's boyhood home in Atlanta and several other nearby buildings were declared as the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site. At the White House Rose Garden on November 2, 1983, U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed a bill creating a federal holiday to honor King. It was observed for the first time on January 20, 1986 and is called Martin Luther King Day. It is observed on the third Monday of January each year, around the time of King's birthday. In January 17, 2000, for the first time, Martin Luther King Day was officially observed in all 50 U.S. states.[43]

In 1998, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity was authorized by the United States Congress to establish a foundation to manage fund raising and design of a Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial. [1] King was a prominent member of Alpha Phi Alpha, the first intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternity established for African Americans. King will be the first African American honored with his own memorial in the National Mall area and the second non-President to be commemorated in such a way. The King Memorial will be administered by the National Park Service.

King is one of the ten 20th-century martyrs from across the world who are depicted in statues above the Great West Door of Westminster Abbey, London. He is also commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America as a renewer of society and martyr on January 15.

Coinage

Coin redesign advocates have asked that King's image be placed on the penny or dime. The penny will be permanently redesigned in 2010, and the current design will no longer be issued beyond 2008, but Abraham Lincoln will remain on the coin. A group of civil rights activists have suggested placing his image on the twenty dollar bill, in place of the racist Andrew Jackson. [2]

Notes

- ^ "Top 100 American Speeches by Rank Order". American Rhetoric. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "Martin Luther King: Beyond Vietnam—A Time to Break Silence". Speech. American Rhetoric. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "E-mail lists "four things you didn't know" about Martin Luther King. Jr". Snopes.com. Retrieved 2007-01-09.

- ^ "The King Center: Biography". The King Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ Scott-King, Correta, My life with Martin Luther King Jr. (New York, 1969) p.124–5

- ^ Haley, Alex (January 1965). "Martin Luther King". The Playboy Interview. Playboy. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Ross, Samuel (2006). "March on Washington". Features. Infoplease. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ King (2000). Why We Can't Wait. Signet Classics. ISBN 0-451-52753-4.

- ^ King, Martin Luther (April 4 1967). "Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence". Speech. Hartford Web Publishing. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Coretta Scott King (ed.). Martin Luther King, Jr., Companion, p. 39. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999.

- ^ Patterson, James T. (January 29 2006). "An epic comes to a close". Chicago Sun-Times. pp. B12. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "1,300 Members Participate in Memphis Garbage Strike". AFSCME. February, 1968. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Memphis Strikers Stand Firm". AFSCME. March, 1968. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rugaber, Walter (March 29 1968). "A Negro is Killed in Memphis". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "1968: Martin Luther King shot dead". On this Day. BBC. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "AFSCME Wins in Memphis". AFSCME. April, 1968. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers' Strike Chronology". AFSCME. 1968. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "1970s". History of Knoxville Office. FBI. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ "James Earl Ray Profile". africanaonline.com. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "The Martin Luther King Assassination". the Real History Archives. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "From small-time criminal to notorious assassin". US news. CNN. 1998. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ "James Earl Ray Dead At 70". CBS. April 23 1998. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Questions left hanging by James Earl Ray's death". BBC. April 23 1998. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Martin Luther King - Sniper in the Shrubbery?". africanaonline.com. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "James Earl Ray, convicted King assassin, dies". US news. CNN. April 23, 1998. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Text of the King family's suit against Loyd Jowers and Martin Luther King Jr.'s "unknown" conspirators". Court TV. 1999. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Pepper, Bill (April 7, 2002). "William F. Pepper on the MLK Conspiracy Trial" (PDF). Rat Haus Reality Press. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Trial Information". Complete Transcript of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Assassination Conspiracy Trial. The King Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ "USDOJ Investigation of Recent Allegations Regarding the Assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr". Overview. USDOJ. June 2000. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ Goodman, Amy (January 15, 2004). "Rev. Jesse Jackson On "Mad Dean Disease," the 2000 Elections and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ayton, Mel (February 28, 2005). "Book review A Racial Crime: The Assassination of MLK". History News Network. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Canedy, Dana (April 6 2002). "My father killed King, says pastor, 34 years on". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

playboywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "MLK Suicide letter". Oilempire.us. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ Jalon, Allan M. (March 8, 2006). "A Break-In to End All Break-Ins". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Church, Frank (April 23, 1976). "Church Committee Book III". Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Case Study. Church Committee. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. upon accepting The Planned Parenthood Federation Of America Margaret Sanger Award". PPFA. 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ^ "Carter Center". Carter Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "The Person of the Century Poll Results". Time magazine. January 19 2000,. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "The King Center". The King Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ Williams, Brandt (January 16 2005). "What would Martin Luther King do?". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Triple Evils". The King Center. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "N.H. becomes last state to honor King with a holiday". The Florida Times Union. June 8, 1999. p. A-4.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

References

- Abernathy, Ralph. And the Walls Came Tumbling Down: An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Row, 1989. ISBN 0-06-016192-2

- Beito, David and Beito, Linda Royster. T.R.M. Howard: Pragmatism over Strict Integrationist Ideology in the Mississippi Delta, 1942–1954 in Glenn Feldman, ed., Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004, 68–95. ISBN 0-8173-5134-5.

- Branch, Taylor. At Canaan's Edge: America In the King Years, 1965–1968. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-684-85712-X

- Carl Edwin Lindgren (Spring, 1992). Tour Resurrects Shantytown Art. Southern Exposure, Vol. XX, No. 1, 7. Information relating to Resurrection City and Dr. King.

- Parting the Waters : America in the King Years, 1954–1963. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0-671-46097-8

- Pillar of Fire : America in the King Years, 1963–1965.: Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN 0-684-80819-6

- Chernus, Ira. American Nonviolence: The History of an Idea, chapter 11. ISBN 1-57075-547-7

- Garrow, David J. The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. New York: Penguin Books, 1981. ISBN 0-14-006486-9

- Jackson, Thomas F., From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8122-3969-0.

- Kirk, John A., Martin Luther King, Jr. London: Pearson Longman, 2005. ISBN 0-582-41431-8

- Ayton, Mel, A Racial Crime: James Earl Ray And The Murder Of Martin Luther King Jr. Archebooks Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-59507-075-3

External links

- This black history resource offers a biography of MLK and links to other related articles.

- The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

- The King Center

- National Civil Rights Museum

- MLK Online Martin Luther King Jr. Speeches, Pictures, Quotes, Biography, Videos, Information on MLK Day and more!

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s, A New Sense of Direction (1968) article published in WorldView magazine.

- Martin Luther King Jr.'s FBI file

- Department of Justice investigation on King assassination

- Martin Luther King in New York

- Martin Luther King Jr. Photographs Photos by Benedict J. Fernandez

- The Seattle Times: Martin Luther King Jr.

- Winner of the 1964 Nobel Prize in Peace

- About.com's Lesser Known Wise and Prophetic Words of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Speeches of Martin Luther King

- Pamphlet on King and Socialism from the Socialist Party USA (PDF)

- "The MLK you don't see on TV" from FAIR

- The Martin Luther King Center (German)

- Works by Martin Luther King, Jr. at Project Gutenberg

- Template:Nndb name

- 1956 Comic Book: "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story"

- Kirk, John A. New Georgia Encyclopedia Short Biography

- Declassified document, FBI's letter urging him to commit suicide.

- Dyson, Michael Eric. No Small Dreams: The Radical Evolution of MLK's Last Years. LiP Magazine, January 2003

- Wise, Tim. Misreading the Dream: The Truth About Martin Luther King Jr. and Affirmative Action. LiP Magazine, January 2003

- Summary of plagiarism controversy

- Shelby County Register of Deeds documents on the Assassination Investigation

- Martin Luther King Philosophy on Nonviolent Resistance

Video and audio material

- Martin Luther King Videos full streaming video speeches on www.MLKOnline.net of "I Have a Dream" and "I've been to the mountaintop"

- Martin Luther King Audio audio recordings of Martin Luther King speeches on www.MLKOnline.net including full "I Have a Dream" speech

- "I Have a Dream" by Common popular new hiphop song sampling Dr. King

- Internet Archive: The New Negro, King interviewed by J. Waites Waring.

- RealAudio recording of the "I Have a Dream" speech at the History Channel's site

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2007

- 1929 births

- 1968 deaths

- African American religious leaders

- African Americans' rights activists

- Alpha Phi Alpha brothers

- American anti-Vietnam War activists

- American Christian socialists

- American humanitarians

- American murder victims

- American religious leaders

- Assassinated activists

- Assassinated American people

- Baptist ministers

- Baptists from the United States

- Boston University alumni

- Bronze Medallion recipients

- COINTELPRO targets

- Community organizing

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths by firearm

- Grammy Award winners

- Lutheran saints

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Morehouse College alumni

- Nobel Peace Prize laureates

- Nonviolence

- People from Atlanta

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Sigma Pi Phi brothers

- Social justice

- Spingarn Medal winners

- Time magazine Persons of the Year

- Baptists