Atheism

Atheism entails, minimally, the absence of belief[1] in the existence of a deity or deities.[2] It is contrasted with theism, the belief in one or more gods. Atheism is commonly defined as the positive belief that deities do not exist, or as the deliberate rejection of theism.[3] However, others define atheism as the simple absence of belief in deities[4] (cf. nontheism), thereby designating many agnostics, and people who have never heard of gods, such as newborn children, as atheists as well.[5] In recent years, some atheists have adopted the terms strong and weak atheism to clarify whether they consider their stance one of positive belief (strong atheism) or the mere absence of belief (weak atheism).[6]

Many self-described atheists share common skeptical concerns regarding supernatural claims, citing a lack of empirical evidence for the existence of deities. Other rationales for atheism range from the philosophical to the social to the historical. Although atheists tend toward secular philosophies such as humanism, rationalism, and naturalism, there is no one ideology or set of behaviors that all atheists adhere to.[7]

In Western culture, atheists are frequently assumed to be irreligious or non-spiritual.[8] However, some religious and spiritual beliefs, such as several forms of Buddhism, have been described by outside observers as conforming to the broader, negative definition of atheism due to their lack of any participating deities.[9][10] Atheism is also sometimes equated with antitheism (opposition to theism) or antireligion (opposition to religion), despite many atheists not holding such views.[11]

Etymology

In early Ancient Greek, the adjective atheos (from privative α- + θεος "god") meant "godless". The word acquired an additional meaning in the 5th Century BCE, severing relations with the gods; that is, "denying the gods, ungodly", with more active connotations than asebēs, or "impious". Modern translations of classical texts sometimes translate atheos as "atheistic". As an abstract noun, there was also atheotēs ("atheism"). Cicero transliterated atheos into Latin. The term found frequent use in the debate between early Christians and pagans, with each side attributing it, in the pejorative sense, to the other.[12]

In English, the term atheism stemmed from the French athéisme in about 1587. The term atheist, in the sense of "one who denies or disbelieves", predates atheism in English, being first attested in about 1571; the Italian atheoi is recorded as early as 1568. Atheist in the sense of practical godlessness was first asserted in 1577. The French word developed from athée ("godless, atheist"), which in turn comes from the Greek atheos. The words deist and theist entered English after atheism, being first attested in 1621 and 1662, respectively, and followed by theism and deism in 1678 and 1682, respectively. Deism and theism changed meanings slightly around 1700, due to the influence of atheism. Deism was originally used as a synonym for today's theism, but came to denote a separate philosophical doctrine.[13]

Originally simply used as a slur for "godlessness",[14] atheism was first used to describe a self-avowed belief in late 18th-century Europe, specifically denoting disbelief in the monotheistic Judeo-Christian God.[15] In the 20th century, globalization contributed to the expansion of the term to refer to disbelief in all deities, though it remains common in Western society to describe atheism as simply "disbelief in God". Additionally, in recent decades there has increasingly been a push in certain philosophical circles to redefine atheism negatively, as "absence of belief in deities" rather than as a belief in its own right; this definition is sometimes contested by theists.[16]

Types and typologies of atheism

Writers have disagreed on how best to define atheism, and much of the literature on the subject is incompatible. There are many terminological discrepancies in discussions of atheism. Disagreement continues about the scope and applicability of atheism, including to those who make no positive assertion, those who have not consciously rejected theism, and those who do not reject all supernatural phenomena.

Scope of atheism

Part of the ambiguity and controversy involved in defining atheism arises from the similar ambiguity and controversy in defining words like deity and God. The plurality of wildly different conceptions of God and deities leads to differing ideas regarding what atheism entails.

In contexts where theism is defined as the belief in a singular personal God, for example, people who believe in a variety of other deities may be classified as atheists, including deists and even polytheists. In the 20th century, this view has fallen into disfavor as theism has come to encompass belief in all divinities, not just the Abrahamic one. However, in the Western world arguments against the Christian God often continue to be seen as arguments for atheism, because of the strong influence of traditional theological thought.[15][17]

A problematic consequence of the broader redefinition of theism is that atheism can be seen as disbelief in almost anything; many pantheists, in particular, believe in a "God" that is synonymous with the natural world, which would make disbelieving in such a God result in disbelief in nature.[18] Increasingly vague, abstract, or figurative conceptions of divinity have led some sources to circumvent the problem by defining atheism as disbelief in all "immaterial beings",[4] rejection of the supernatural world altogether, or simply as irreligion.[8] However, god-centered definitions of atheism remain more common.

Pejorative definition: atheism as immorality

Emblem illustrating atheism as immorality, titled "Supreme Impiety: Atheist and Charlatan", from Picta poesis, by Barthélemy Aneau, 1552.

Opponents of atheism have frequently associated atheism with immorality and evil, often characterizing it as a willful and malicious repudiation of God or gods. This, in fact, is the original definition and sense of the word, but changing sensibilities and the normalization of non-religious viewpoints have caused the term to lose most of its pejorative connotations.

The first attempts to define a typology of atheism were in religious apologetics. A diversity of atheist opinion has been documented since Plato, and common distinctions have been established between practical atheism and speculative or contemplative atheism. Practical atheism was associated with moral failure, hypocrisy, willful ignorance and infidelity. Its proponents were said to behave as though God, morals, ethics and social responsibility did not exist; they abandoned duty and embraced hedonism. Jacques Maritain's 1953 typology of atheism proved influential in Catholic circles;[20] it was followed in the New Catholic Encyclopedia.[21] He identified, in addition to practical atheism, pseudo-atheism and absolute atheism, and subdivided theoretical atheism in a way that anticipated Antony Flew.[22]

According to the French Catholic philosopher Étienne Borne, "Practical atheism is not the denial of the existence of God, but complete godlessness of action; it is a moral evil, implying not the denial of the absolute validity of the moral law but simply rebellion against that law."[23] Karen Armstrong states that "During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the word 'atheist' was still reserved exclusively for polemic.... The term 'atheist' was an insult. Nobody would have dreamed of calling himself an atheist."[24]

On the other hand, the existence of serious, speculative atheism was often denied. It was thought impossible to reason one's way to atheism. The existence of God was considered self-evident; this is why Borne finds it necessary to respond that "to put forward the idea, as some apologists rashly do, that there are no atheists except in name but only practical atheists who through pride or idleness disregard the Divine law, would be, at least at the beginning of the argument, a rhetorical convenience or an emotional prejudice evading the real question".[25]

Nevertheless, when denial of the existence of speculative atheism became unsustainable, atheism was continually repressed and criticized by narrowing definitions, applying charges of dogmatism, and otherwise misrepresenting atheist positions. One of the reasons for the popularity of euphemistic alternative terms like secularist, empiricist, agnostic, or Bright is that atheism still has pejorative connotations arising from attempts at suppression and from its association with practical atheism; like the word godless, may still be used as an abusive epithet today.[26][27][28] J.C.A. Gaskin abandoned the term atheism in favor of unbelief, citing "the pejorative associations of the term, its vagueness, and later the tendency of religious apologists to define atheism so that no one could be an atheist".[29] However, many atheists persist in using the term and seek to change its connotations.[30]

In modern times, opponents continue to conflate atheism with such beliefs as communism, nihilism, irreligion, and antitheism. Antitheism typically refers to a direct opposition to theism; however, antitheism has also been used, particularly in religious contexts, to refer to opposition to God or divinity, rather than to the belief in God.[31] Under the latter definition, it may actually be necessary to be a theist in order to be an antitheist, to oppose God itself and not the idea of God. This position is seldom expressed, though opponents of atheism often claim that atheists hate God. Under the former definition, antitheists may be atheists who believe that theism is harmful to human progression, or simply ones who have little tolerance for views they perceive as irrational (cf. faith and rationality).[32] A related stance is militant atheism, which is generally characterized by antireligious views.[33]

Positive definition: atheism as the belief that no deities exist

There are three major traditions in defining atheism and its subdivisions. The first tradition understands atheism very broadly, as including both those who believe that no god or gods exist (strong atheism) and those who are simply not theists (weak atheism). George H. Smith, Michael Martin, and Antony Flew fall into this tradition, though they do not use the same terminology. The second tradition understands atheism more narrowly, as the conscious rejection of theism, and does not consider absence of theistic belief or suspension of judgment concerning theism to be forms of atheism. Ernest Nagel, Paul Edwards and Kai Nielsen are prominent members of this camp.

A third tradition, seldom used by atheists, understands atheism even more narrowly than that. Here, atheism is defined in the strongest possible terms, as the positive belief that there are no deities. Under this definition, all weak atheism, whether implicit or explicit, is non-atheistic. However, this usage is not exclusive to theists; atheistic philosopher Theodore Drange uses this definition.[34]

The definition of atheism as a "belief" or "doctrine" reflects a view of atheism as a specific ideological stance, as opposed to the rejection or simple absence of a belief.[35]

In philosophical and atheist circles, however, this definition is often disputed and even rejected. The broader, negative definition has become increasingly popular in recent decades, with many specialized textbooks dealing with atheism favoring it.[36] One prominent atheist writer who disagrees with the broader definition of atheism, however, is Ernest Nagel, who considers atheism to be the rejection of theism (which George H. Smith labeled as explicit atheism, or anti-theism): "Atheism is not to be identified with sheer unbelief... Thus, a child who has received no religious instruction and has never heard about God is not an atheist—for he is not denying any theistic claims."[37]

Some atheists argue for a positive definition of atheism on the basis that defining atheism negatively, as "the negation of theistic belief", makes it "parasitic on religion" and not an ideology in its own right. While most atheists welcome having atheism cast as non-ideological, in order to avoid potentially framing their view as one requiring "faith", writers such as Julian Baggini prefers to analyze atheism as part of a general philosophical movement towards naturalism in order to emphasize the explanatory power of a non-supernatural worldview.[38] Baggini rejects the negative definition based on his view that it implies that atheism is dependent on theism for its existence: "atheism no more needs religion than atheists do".[39] Harbour,[40] Thrower,[41] and Nielsen, similarly, have used philosophical naturalism to make a positive argument for atheism. Michael Martin notes that the view that "naturalism is compatible with nonatheism is true only if 'god' is understood in a most peculiar and misleading way", but he also points out that "atheism does not entail naturalism".[42]

Negative definition: atheism as the absence of belief in deities

Among modern atheists, the view that atheism simply means "without theistic beliefs" has a great deal of currency.[43] This very broad definition is often justified by reference to the etymology (cf. privative a),[6][44] as well as to the consistent usage of the word by atheists.[45] However, others have dismissed the former justification as an etymological fallacy and the latter on the grounds that majority usage outweighs minority usage.[46]

Although this definition of atheism is frequently disputed, it is not a recent invention; as far back as 1772, d'Holbach said that "All children are born Atheists; they have no idea of God".[47] More recently, science fiction author George H. Smith (1979) put forth a similar view:

"The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child without the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist."[48]

Smith coined the terms implicit atheism and explicit atheism to avoid confusing these two varieties of atheism. Implicit atheism is defined by Smith as "the absence of theistic belief without a conscious rejection of it", while explicit atheism—the form commonly held to be the only true form of atheism—is an absence of theistic belief due to conscious rejection.

Many similar dichotomies have since sprung up to subcategorize the broader definition of atheism. Strong, or positive, atheism is the belief that gods do not exist. It is a form of explicit atheism. A strong atheist consciously rejects theism, and may even argue that certain deities logically cannot exist, although strong atheists rarely claim to have certain knowledge that no deities exist.[49] Weak, or negative, atheism is either the absence of the belief that gods exist (in which case anyone who is not a theist is a weak atheist), or of both the belief that gods exist and the belief that they do not exist (in which case anyone who is neither a theist nor a strong atheist is a weak atheist).[6][50] While the terms weak and strong are relatively recent, the concepts they represent have existed for some time. The terms negative atheism and positive atheism have been used in the philosophical literature[51] and (in a slightly different sense) in Catholic apologetics.[52]

Contrary to the common view of theological agnosticism—the denial of knowledge or certainty of the existence of deities—as a "midway point" between theism and atheism, under this understanding of atheism, many agnostics may qualify as weak atheists (cf. agnostic atheism). However, others may be agnostic theists. Many agnostics and/or weak atheists are critical of strong atheism, seeing it as a position that is no more justified than theism, or as one that requires equal "faith".[53][54]

History

Although the term atheism originated in 16th-century France, ideas that would be recognized today as atheistic existed before the advent of Classical antiquity. Eastern philosophy has a long history of nontheistic belief, beginning in the 6th century BC with the rise of Jainism, Buddhism, and certain sects of Hinduism in India, and of Taoism in China.

Western atheism has its roots in ancient Greek philosophy, but did not emerge as a distinct world-view until the late Enlightenment.[55] The 5th-century BCE Greek philosopher Diagoras is known as the "first atheist", and strongly criticized religion and mysticism. Epicurus was an early philosopher to dispute many religious beliefs, including the existence of an afterlife or a personal deity. Other pre-Socratic philosophers with atheistic views included Prodicus, Protagoras, Theodorus, Leucippus, and Democritus.

Atheists have been subject to significant persecution and discrimination throughout history. Atheism has been a criminal offense in many parts of the world, and in some cases, a "wrong belief" was equated with "unbelief" in order to condemn someone with differing beliefs as an "atheist". For example, despite having expressed belief in various divinities, Socrates was called an atheist, and ultimately sentenced to death for impiety on the basis that he inspired questioning of the state gods.[56][57] During the late Roman Empire, many Christians were executed for "atheism" because of their rejection of the Roman gods, and "heresy" and "godlessness" were serious capital offenses following the rise of Christianity.

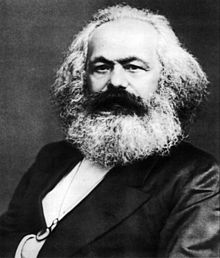

Atheistic sentiment was virtually unknown in medieval Europe, but flourished in the empirical Carvaka school of India. Criticism of religion became increasingly frequent in the 16th century, and the word athéisme originated as a slur—invariably denied by the accused—used against such critics, as well as against deists, scientists, and materialists.[58] The first openly atheistic thinkers, such as Baron d'Holbach, appeared in the late 18th century, when expressing disbelief in God became a less dangerous position.[59] Following the French Revolution, atheism rose to prominence under the influence of rationalistic and freethinking philosophies, and many prominent 19th-century German philosophers denied the existence of deities and were critical of religion, including Arthur Schopenhauer, Karl Marx, and Friedrich Nietzsche (see "God is dead").[60][61]

In the 20th century, atheism, though still a minority view, became increasingly common in many parts of the world, often included as an aspect of a wide variety of other, broader philosophies, such as existentialism, Objectivism, secular humanism, nihilism, relativism, logical positivism, Marxism, feminism,[62] and the general scientific and rationalist movement. In some cases, these philosophies became associated with atheism to the extent that atheists were vilified for the broader view, such as when the word atheist entered popular parlance in the United States as synonymous with being unpatriotic (cf. "godless commie") during the Cold War. Some "Communist states", such as the Soviet Union, promoted state atheism and opposed religion, often by violent means;[63] Enver Hoxha went further than most and officially banned religion, declaring Albania the world's first Atheist state. These policies helped reinforce the negative associations of atheism, especially where anti-communist sentiment was strong, despite the fact that many prominent atheists, such as Ayn Rand, were anti-communist.[64]

Other notable atheists in recent times have included comedian Woody Allen,[65] biologist Richard Dawkins,[66] actress Katharine Hepburn,[67] author Douglas Adams,[68] philosopher Bertrand Russell,[69] dictator Joseph Stalin,[70] and activist Margaret Sanger.[65]

Demographics

It is difficult to quantify the number of atheists in the world. Different people interpret "atheist" and related terms differently, and it can be hard to draw boundaries between atheism, non-religious beliefs, and non-theistic religious and spiritual beliefs. Furthermore, atheists may not report themselves as such, to prevent suffering from social stigma, discrimination, and persecution in certain regions.

Despite these problems, atheism is relatively common in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, former and present Communist states, and to a lesser extent, the United States. A 1995 survey attributed to the Encyclopædia Britannica indicates that the non-religious make up about 14.7% of the world's population, and atheists around 3.8%.[71]

According to a study by Paul Bell, published in the Mensa Magazine in 2002, there is an inverse correlation between religiosity and intelligence. Analyzing 43 studies carried out since 1927, Bell finds that all but four reported such a connection, and concludes that "the higher one's intelligence or education level, the less one is likely to be religious or hold 'beliefs' of any kind." A survey published in Nature confirms that belief in a personal god or afterlife is at an all time low among the members of the National Academy of Science, only 7.0% of which believed in a personal god as compared to more than 85% of the US general population.[72]

A recent poll (November-December 2006) published in the Financial Times gives more recent rates for the USA and five European countries; this poll shows that Americans are more likely than Europeans to believe in any form of God or Supreme Being (73%). Of the European adults surveyed, Italians are the most likely to express this belief (62%) and, in contrast, the French are the least likely (27%). In France, 32% declared themselves to be atheists, with an additional 32% declaring themselves agnostic.[73]

Atheist organizations

Noteworthy organizations that are atheistic or promote related freethinking inquiry include:

Many organizations that promote skepticism of paranormal claims have goals similar to those of freethought and atheistic organizations, but remain officially neutral on the existence of God. Examples include Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), The Skeptics Society, and the James Randi Educational Foundation.

In 2002, a group of people organized the "Godless Americans March on Washington". Though it was broadcast on C-SPAN, the march was not well attended and received little or no press coverage.

Atheism, religion and morality

Although people who self-identify as being atheists are almost invariably assumed to be irreligious, there are many atheists who describe themselves as adhering to a certain religion, and even major religions that have been described as having atheistic leanings, particularly under the negative definition. Atheism in Hinduism, in Buddhism, and in other Eastern religions has an especially long history,[9][74] but in recent years certain liberal religious denominations have accumulated a number of openly atheistic followers, such as Jewish atheists (cf. humanistic Judaism)[75][76] and Christian atheists (cf. Unitarian Universalism).[77][78][79]

As atheism does not entail any specific beliefs outside of disbelief in God, atheists can hold any number of spiritual beliefs. For the same reason, atheists can hold a wide variety of ethical beliefs, ranging from the moral universalism of humanism, which holds that a moral code (such as utilitarianism) should be applied consistently to all humans (cf. human rights), to moral nihilism, which holds that morality is meaningless.[80]

However, throughout its history, atheism has commonly been equated with immorality, based on the belief that morality is directly derived from God, and thus cannot be attained without appealing to God.[81][82] Moral precepts such as "murder is wrong" are seen as divine laws, requiring a divine lawmaker and judge. However, many atheists argue that treating morality legalistically involves a false analogy, and that morality does not depend upon a lawmaker in the same way that laws do,[83] based on the Euthyphro dilemma, which either renders God unnecessary or morality arbitrary.[84] Some atheists also assert that behaving ethically only because of divine mandate is not true ethical behavior, merely blind obedience.[85]

Some atheists, in fact, have argued that atheism is a superior basis for ethics than theism. It is argued that a moral basis external to religious imperatives is necessary in order to evaluate the morality of the imperatives themselves—to be able to discern, for example, that "thou shalt steal" is immoral even if one's religion instructs it—and that therefore atheists have the advantage of being more inclined to make such evaluations.[86]

Atheists such as Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris have argued that Western religions' reliance on divine authority lends itself to authoritarianism and dogmatism.[87] This argument, combined with historical events that are argued to demonstrate the dangers of religion, such as the inquisitions and witch trials, is often used by antireligious atheists to justify their views;[88] however, theists have made very similar arguments against atheists based on the state atheism of communist states.[89] In both cases, critics argue that the connection is a weak one based on the correlation implies causation and guilt by association fallacies.

Other individuals from within the atheist community have criticized the movement's inability to find a secular basis of morality outside of the supernatural and hypothetical. Friedrich Nietzsche sums this failure in his famous God is dead quote. He complains that one arbitrary basis of morality (divine mandate) is replaced by another arbitrary basis. In essence, all moral philosophies share the same strengths and failures.

Reasons for atheism

Proponents of atheism assert various reasons for their position, including a lack of empirical evidence for deities, or the conviction that the non-existence of deities (in general or particular) is better supported rationally.

Scientific and historical reasons

Science is based on the observation that the universe is governed by natural laws that can be discerned through repeatable experiments. Science serves as a reliable, rational basis for predictions and engineering (cf. faith and rationality, science and religion). Like scientists, scientific skeptics use critical thinking (cf. the true-believer syndrome) to decide claims, and do not base claims on faith or other unfalsifiable categories. Some philosophers and academics, such as philosopher Jurgen Habermas, adhere to "methodological atheism", a more specific form of science's methodological naturalism, to indicate that whatever their personal beliefs, they do not include theistic presuppositions in their methods for learning about or explaining the world.[90]

Most theistic religions teach that mankind and the universe were created by one or more deities and that this deity continues to act in the universe. Many people—theists and atheists alike—feel that this view conflicts with the discoveries of modern science (especially in cosmology, astronomy, biology and quantum physics). Many believers of the validity of science, seeing such a contradiction, do not believe in the existence of a deity or deities actively involved in the universe.

Science presents a vastly different view of humankind's place in the universe from theistic religions. Scientific progress has continually eroded the basis for religion. Historically, religions have involved supernatural entities and forces linked to unexplained physical phenomena. In ancient Greece, for instance, Helios was the god of the sun, Zeus the god of thunder, and Poseidon the god of earthquakes and the sea. In the absence of a credible scientific theory explaining phenomena, people attributed them to supernatural forces. Science has since eliminated the need for appealing to supernatural explanations. The idea that the role of deities is to fill in the remaining "gaps" in scientific understanding has come to be known as the God of the gaps.[91]

Anthropologists consider religions to be social constructs (see development of religion) that should be analyzed with an unbiased, historical viewpoint. Atheists often argue that nearly all cultures have their own creation myths and gods, and there is no apparent reason to believe that a certain god (e.g., Yahweh) has a special status above gods otherwise not believed to be real (e.g., Zeus), or that one culture's god is more correct than another's. In the same way, all cultures have different, and often incompatible, religious beliefs, none any more likely to be true than another, making the selection of a single specific religion seemingly arbitrary.[92]

However, when theological claims move from the specific and observable to the general and metaphysical, atheistic objections tend to shift from the scientific to the philosophical:

"Within the framework of scientific rationalism one arrives at the belief in the nonexistence of God, not because of certain knowledge, but because of a sliding scale of methods. At one extreme, we can confidently rebut the personal Gods of creationists on firm empirical grounds: science is sufficient to conclude beyond reasonable doubt that there never was a worldwide flood and that the evolutionary sequence of the Cosmos does not follow either of the two versions of Genesis. The more we move toward a deistic and fuzzily defined God, however, the more scientific rationalism reaches into its toolbox and shifts from empirical science to logical philosophy informed by science. Ultimately, the most convincing arguments against a deistic God are Hume's dictum and Occam's razor. These are philosophical arguments, but they also constitute the bedrock of all of science, and cannot therefore be dismissed as non-scientific. The reason we put our trust in these two principles is because their application in the empirical sciences has led to such spectacular successes throughout the last three centuries."[93]

Philosophical and logical reasons

Many atheists will point out that in philosophy and science, the default position on any matter is a lack of belief. If reliable evidence or sound arguments are not presented in support of a belief, then the "burden of proof" remains upon believers, not nonbelievers, to justify their view.[94][95] Consequently, many atheists assert that they are not theists simply because they remain unconvinced by theistic arguments and evidence. As such, many atheists have argued against the most famous proposed proofs of God's existence, including the ontological, cosmological, and teleological arguments.[96]

Other atheists base their position on a more active logical analysis, and subsequent rejection, of theistic claims. The arguments against the existence of God aim at showing that the traditional Judeo-Christian conception of God either is inherently meaningless, is internally inconsistent, or contradicts known scientific or historical facts, and that therefore a god thus described does not exist.

The most common of these arguments is the problem of evil, which Christian apologist William Lane Craig has called "atheism's killer argument."[97] The argument is that the presence of evil in the world disproves the existence of any god that is simultaneously benevolent and omnipotent, because any benevolent god would want to eliminate evil, and any omnipotent god would be able to do so. Theists commonly respond by invoking free will to justify evil (cf. argument from free will). However, this leaves unresolved the related argument from nonbelief, also known as the argument from divine hiddenness, which states that if an omnipotent God existed and wanted to be believed in by all, it would prove its existence to all because it would invariably be able to do so. Since there are unbelievers, either there is no omnipotent God or God does not want to be believed in.

Another such argument is theological noncognitivism, which holds that religious language, and specifically words like God, is not cognitively meaningful. This argument was popular in the early 20th century among logical positivists such as Rudolph Carnap and A.J. Ayer, who held that talk of deities is literally nonsense.[98] Such arguments have since fallen into disfavor among philosophers, but continue to see use among ignostics, who view the question of whether deities exist as meaningless or unanswerable, and apatheists, who view it as entirely irrelevant. Similarly, the transcendental argument for the non-existence of God (TANG), a reversal of the more well-known theistic argument, argues that logic, science, and morality can only be justified by appealing to a non-theistic worldview.

Personal, social, and ethical reasons

Some atheists have found social, psychological, practical, and other personal reasons for their disbelief. Some believe that it is more conducive to living well, or that it is more ethical and has more utility than theism. Such atheists may hold that searching for explanations in natural science is more beneficial than seeking to explain phenomena supernaturally. Some atheists also assert that atheism allows—or perhaps even requires—people to take personal responsibility for their actions. In contrast, they feel that many religions blame bad deeds on extrinsic factors and require threats of punishment and promises of reward to keep a person morally and socially acceptable.

Some atheists dislike the restrictions religious codes of conduct place on their personal freedoms. From their point of view, such morality is subjective and arbitrary. Some atheists even argue that theism can promote immorality. Much violence—e.g., warfare, executions, murders, and terrorism—has been brought about, condoned, or justified by religious beliefs and practices.

In areas dominated by certain Christian denominations, many atheists find it difficult to accept that faith could be more important than good works: While a murderer can go to heaven simply by accepting Jesus in some Christian sects, a farmer in a remote Asian countryside will go to hell for not hearing the "good news". Furthermore, some find Hell to be the epitome of cruel and unusual punishment, making it impossible that a good God would permit such a place's existence.

Just as some people of faith come to their faith based upon perceived spiritual or religious experiences, some atheists base their view on an absence of such an experience (or on explaining such experiences through natural causes). Although they may not foreclose the possibility of a supernatural world, unless they believe through experience that such a world exists, they generally refuse to accept a metaphysical belief system based upon faith.

Some atheists argue that religion's emphasis on "faith" can undermine the desire to continually seek new knowledge and explanations.[99] For example, if it is accepted that God created life, then there is no need to research how life arose. Stephen Hawking noted in his book "A Brief History of Time" that the Pope urged him and other scientists not to delve into the origin of the universe because that area belonged to God.

Additionally, some atheists grow up in environments where atheism is relatively common, just as people who grow up in a predominantly Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, or Christian cultures tend to adopt the prevalent religion there. However, because of the relative uncommonness of atheism, a majority of atheists were not brought up in atheist households or communities.

Footnotes and citations

- ^ Various dictionaries give a range of definitions for disbelief, from "lack of belief" to "doubt" and "withholding of belief" to "rejection of belief", "refusal to believe", and "denial". Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Some dictionary definitions:

- "1. the doctrine or belief that there is no God. 2. disbelief in the existence of a supreme being or beings." Template:Ref harvard

- "1. a. Disbelief in or denial of the existence of God or gods. Including the existence of the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim God. b. The doctrine that there is no God or gods. 2. Godlessness; immorality." Template:Ref harvard

- "1 archaic : UNGODLINESS, WICKEDNESS 2 a : a disbelief in the existence of deity b : the doctrine that there is no deity" Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Rejection of theism:

- "Unlike agnosticism, which leaves open the question of whether there is a God, atheism is a positive denial." Template:Ref harvard

- "Atheism is the position that affirms the nonexistence of God. It proposes positive belief rather than mere suspension of disbelief." Template:Ref harvard

- "Atheism is fundamentally a rejection of belief in any God. It is more than a simple lack of belief, as children and some members of tribal societies may not believe out of ignorance." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ a b Absence of belief:

- "Atheists are people who do not believe in a god or gods (or other immaterial beings), or who believe that these concepts are not meaningful. Some atheists put it more firmly and believe that god or gods do not exist." Template:Ref harvard

- "The broader, and more common, understanding of atheism among atheists is quite simply 'not believing in any gods.' No claims or denials are made—an atheist is just a person who does not happen to be a theist." Template:Ref harvard

- "The average theologian (there are exceptions, of course) uses 'atheist' to mean a person who denies the existence of a God. Even an atheist would agree that some atheists (a small minority) would fit this definition. However, most atheists would strongly dispute the adequacy of this definition. Rather, they would hold that an atheist is a person without a belief in God. The distinction is small but important. Denying something means that you have knowledge of what it is that you are being asked to affirm, but that you have rejected that particular concept. To be without a belief in God merely means that the term 'god' has no importance or possibly no meaning to you. Belief in God is not a factor in your life. Surely this is quite different from denying the existence of God. Atheism is not a belief as such. It is the lack of belief." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Atheists by default:

- ^ a b c Strong vs. Weak Atheism:

- "If you look up 'atheism' in a dictionary, you will find it defined as the belief that there is no God. Certainly, many people understand 'atheism' in this way. Yet this is not what the term means if one considers it from the point of view of its Greek roots. In greek 'a' means 'without' or 'not,' and 'theos' means 'god.' From this standpoint, an atheist is someone without a belief in God; he or she need not be someone who believes that God does not exist. Still, there is a popular dictionary meaning of 'atheism' according to which an atheist is not simply one who holds no belief in the existence of God or gods but is one who believes that there is no God or gods. This dictionary use of the term should not be overlooked. To avoid confusion, let us call it positive atheism and let us call the type of atheism derived from the original Greek roots negative atheism." Template:Ref harvard

- Template:Ref harvard

- "Atheism is commonly divided into 'weak' and 'strong.' Weak atheists have no faith, simply because the feeling is not there. Strong atheists conclude, from existing evidence and arguments, that gods do not exist." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ No one atheist ideology:

- Template:Ref harvard

- "The atheist's rejection of belief in God is usually accompanied by a broader rejection of any supernatural or transcendental reality. For example, an atheist does not usually believe in the existence of immortal souls, life after death, ghosts, or supernatural powers. Although strictly speaking an atheist could believe in any of these things and still remain an atheist... the arguments and ideas that sustain atheism tend naturally to rule out other beliefs in the supernatural or transcendental." Template:Ref harvard

- "Neither atheism nor agnosticism is a full belief system, because they have no fundamental philosophy or lifestyle requirements. These forms of thought are simply the absence of belief in, or denial of, the existence of deities." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ a b "Atheism, however, casts a wider net and rejects all belief in 'spiritual beings,' and to the extent that belief in spiritual beings is definitive of what it means for a system to be religious, atheism rejects religion. So atheism is not only a rejection of the central conceptions of Judeo-Christianity and Islam, it is, as well, a rejection of the religious beliefs of such African religions as that of the Dinka and the Nuer, of the anthropomorphic gods of classical Greece and Rome, and of the transcendental conceptions of Hinduism and Buddhism. Generally atheism is a denial of God or of the gods, and if religion is defined in terms of belief in spiritual beings, then atheism is the rejection of all religious belief." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ a b "Nonbelief has existed for centuries. For example, Buddhism and Jainism have been called atheistic religions because they do not advocate belief in gods." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Lots of people in the West misunderstand Buddhism, especially it's [sic] general lack of any divine figures. They don't realize that, for many, Buddhism is essentially an atheistic religion. People in the West are accustomed to religions all being theistic, so the idea of an atheistic religion is almost incomprehensible." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "As someone who is reasonably familiar with atheist literature, I am not aware of anyone who identifies themselves as an 'antitheist.'... I suspect (though I cannot prove) that the real reason Zacharias prefers the word 'antitheist' is because of its negative connotations." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Atheism and atheist are words formed from Greek roots and with Greek derivative endings. Nevertheless they are not Greek; their formation is not consonant with Greek usage. In Greek they said atheos and atheotes; to these the English words ungodly and ungodliness correspond rather closely. In exactly the same way as ungodly, atheos was used as an expression of severe censure and moral condemnation; this use is an old one, and the oldest that can be traced. Not till later do we find it employed to denote a certain philosophical creed." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary also records an earlier, irregular formation, atheonism, dated from about 1534. The later and now obsolete words athean and atheal are dated to 1611 and 1612, respectively. Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ a b In part because of its wide use in monotheistic Western society, atheism is often described as "disbelief in God", rather than more generally as "disbelief in deities". A clear distinction is rarely drawn in modern writings between these two definitions, but some archaic uses of atheism encompassed only disbelief in the singular God, not in polytheistic deities. It is on this basis that the obsolete term adevism was coined in the late 19th century to describe an absence of belief in plural deities. Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "There is, unfortunately, some disagreement about the definition of atheism. It is interesting to note that most of that disagreement comes from theists — atheists themselves tend to agree on what atheism means."Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "The concept of atheism was developed historically in the context of Western monotheistic religions, and it still has its clearest application in this area." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Atheist philosopher Wallace I. Matson distinguishes deity from God, where deity refers to "personal, superhuman active and powerful intelligence, while God refers to "infinite Being—infinite in the respects of knowledge and wisdom, power and goodness." However, distinctions between these terms are uncommon and often inconsistent with each other. Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Translation of Latin text from "Summa impietas" (1552), Picta poesis, by Barthélemy Aneau. Glasgow University Emblem Website. URL accessed 2007-03-26.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Charles Bradlaugh once said, in debate with George Holyoake on March 10, 1870, "I maintain that the opprobrium cast upon the word Atheism is a lie. I believe Atheists as a body to be men deserving respect... I do not care what kind of character religious men may put round the word Atheist, I would fight until men respect it." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "I'm not even an atheist so much as I am an antitheist; I not only maintain that all religions are versions of the same untruth, but I hold that the influence of churches, and the effect of religious belief, is positively harmful." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Atheism which is actively hostile to religion I would call militant. To be hostile in this sense requires more than just strong disagreement with religion—it requires something verging on hatred and is characterized by a desire to wipe out all forms of religious belief. Militant atheists tend to make one or both of two claims that moderate atheists do not. The first is that religion is demonstrably false or nonsense, and the second is that it is usually or always harmful." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Some writers on this topic take the term 'atheism' to refer merely to a lack of theistic belief. That would be a kind of catch-all use of the term. Atheism would then include not only the view that "God exists" expresses a false proposition, but also noncognitivism, general agnosticism, and cognitivist agnosticism. Not only would such a definition blur and neglect all those distinctions, but it would also be a departure from the most common use of the term 'atheism' in English. For these reasons, it is an inferior definition. For a word to represent the lack of theistic belief, I recommend 'nontheism' for that purpose. It is a word that does not already have some other use in ordinary language." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "The works cited below are all specialized reference materials, designed not to provide general information for a general audience but, rather, information on specific topics like religion, sociology, or other social sciences. Their value here is in the fact that they provide some insight into what scholars from different specialized fields think of when it comes to the concept of atheism. As you will see, very often they use the broader understanding of atheism rather than the narrower one we sometimes encounter." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "The strength of modern atheism is that it is founded more upon positive atheism than negative; rather than just a rejection of contemporary religious beliefs, modern atheism offers a seemingly complete philosophy of the world around us. The contemporary atheist not only sees much that is dubious in Christianity, but sees much that is redundant and just less satisfying than what is provided by modern education, science, anthropology and material culture." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Much atheism... can be understood only in the light of the current theism which it was concerned to reject. Such atheism is relative. There is, however, a way of looking at and interpreting events in the world, whose origins... can be seen as early as the beginnings of speculative thought itself, and which I shall call naturalistic, that is atheistic per se, in the sense that it is incompatible with any and every form of supernaturalism... naturalistic or absolute atheism is both fundamentally more important, and more interesting, representing as it does one polarity in the development of the human spirit." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "If you look up 'atheism' in the dictionary, you will probably find it defined as the belief that there is no God. Certainly many people understand atheism in this way. Yet many atheists do not, and this is not what the term means if one considers it from the point of view of its Greek roots. In Greek 'a' means 'without' or 'not' and 'theos' means 'god.' From this standpoint an atheist would simply be someone without a belief in God, not necessarily someone who believes that God does not exist. According to its Greek roots, then, atheism is a negative view, characterized by the absence of belief in God." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "This is evident in its very name—atheism is a-theism: the negation of theistic belief.... I think this view is profoundly mistaken. Its initial plausibility is based on a very crude piece of flawed reasoning we can call the etymological fallacy. This is the mistake of thinking that one can best understand what a word means by understanding its origin." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Although most strong atheists rarely do not claim certainty of the nonexistence of deities or the supernatural, gnostic atheists such as Paul Keller do exist. Gnostic atheism is the position that it is known by facts and reason alone that there is no god and no supernatural.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Maritain, Jacques (1949). "On the Meaning of Contemporary Atheism". The Review of Politics. 11 (3): 267–280.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "When people say that atheism is a faith position, what they tend to think is that, since there is no proof for atheism, something extra—faith—is required to justify belief in it. But this is simply to misunderstand the role of proof in the justification for belief.... A lack of proof is no grounds for the suspension of belief. This is because when we have a lack of absolute proof we can still have overwhelming evidence or one explanation which is far superior to the alternatives." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Smart, J.C.C. (2004). "Atheism and Agnosticism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ "Atheism had its origins in Ancient Greece but did not emerge as an overt and avowed belief system until late in the Enlightenment." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Plato. Apology.[1]

- ^ "Atheism (Philosophy, Terms and Concepts)". AllRefer.com. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Price, Geoff (2005). "A Historical Outline of Modern Religious Criticism in Western Civilization". Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ^ "Western atheism, as a movement opposing religion, developed in the 19th century, and became widely accepted by intellectuals." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr I. The Gulag Archipelago. Harper Perennial Modern Classics. ISBN 0-06-000776-1.

- ^ Rafford, R.L. (1987). "Atheophobia - an introduction". Religious Humanism. 21 (1): 32–37.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help) - ^ a b Haught, James A. (1996). 2,000 Years of Disbelief: Famous People with the Courage to Doubt. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-067-3.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2002). "Positiveatheism.org A Challenge To Atheists: Come Out of the Closet", in Free Inquiry.

- ^ Ladies' Home Journal, October 1991.[2]

- ^ Silverman, David. "Life, the Universe, and Everything: An Interview with Douglas Adams", in The American Atheist Volume 37 No. 1.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1967). Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. ISBN 0-671-20323-1.

- ^ Yaroslavsky, E. (1940). Landmarks in the Life of Stalin. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

- ^ "Worldwide Adherents of All Religions by Six Continental Areas, Mid-1995". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "Leading scientists still reject God". Nature. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ^ "Religious Views and Beliefs Vary Greatly by Country, According to the Latest Financial Times/Harris Poll". Financial Times. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ "Traditional Buddhism has taught that either there are no gods or, if there are, they aren't worth bothering with—but people being people, gods have been added to Buddhist practice over the centuries. They aren't creator gods like we find in western religion, but they are gods nonetheless. Not all Buddhists are atheists, but there are quite a few." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Humanistic Judaism". BBC. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Christian Atheism". BBC. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "To view atheism as a way of life, whether beneficial or harmful, is false and misleading. Just as the failure to believe in magic elves does not entail a code of living or a set of principles, so the failure to believe in a god does not imply any specific philosophical system. From the mere fact that a person is an atheist, one cannot infer that this person subscribes to any particular positive beliefs. One's positive convictions are quite distinct from the subject of atheism. While one may begin with a basic philosophical position and infer atheism as a consequence of it, this process cannot be reversed." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "One cannot criticize religious dogmatism for long without encountering the following claim, advanced as though it were a self-evident fact of nature: there is no secular basis for morality." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Among the many myths associated with religion, none is more widespread—or more disastrous in its effects—than the myth that moral values cannot be divorced from the belief in a god." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "One can have immoral laws as well as moral ones. What is required for just laws is for the legislature and judiciary to act within the confines of morality. Morality is thus... the basis upon which just laws are enacted and enforced; it is not constituted by the laws themselves." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "The Euthypryo dilemma is a very powerful argument against the idea that God is required for morality. Indeed, it goes further and shows that God cannot be the source of morality without morality becoming something arbitrary." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "More profoundly, it is an odd morality that thinks that one can only behave ethically if one does so out of fear of punishment or promise of reward. The person who doesn't steal only because they fear they will be caught is not a moral person, merely a prudent one. The truly moral person is the one who has the opportunity to steal without being caught but still does not do so." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "It is easy for the religious believer to think that they can avoid choice just by listening to the advice of their holy men (it is usually men) and sacred texts. But since adopting this attitude can lead to suicide bombings, bigotry, and other moral wrongs, it should be obvious that it does not absolve one of moral responsibility. So although the idea of individuals making moral choices for themselves may sound unpalatable to those used to thinking about morality deriving from a single authority, none of us can avoid making such choices." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "In a world riven by ignorance, only the atheist refuses to deny the obvious: Religious faith promotes human violence to an astonishing degree." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Richard John Neuhaus (April 2005). "The Public Square". First Things (152): 57–72. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ Thomas, Mark. "Why Atheism?". Atheists of Silicon Valley.

- ^ "Atheism also has great explanatory power when it comes to the existence of divergent religious beliefs. The best explanation for the fact that different religious people believe different things about God and the universe throughout the world is that religion is a human construct that does not correspond to any metaphysical reality. The alternative is that many religions exist but only one (or a few) are true." Template:Ref harvard

- ^ "Personal Gods, Deism, & the Limits of Skepticism". Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Cline, Austin (2006). "What is Atheism?: Narrow vs. Broad Definitions of Atheism". about.com. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ "Ebon Musings: The Atheism Pages". Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Craig, William Lane (2003). God?. Oxford University Press. pp. p. 112. ISBN 0195165993.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:Ref harvard

- ^ Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion

References

|

|

External links

- Open Directory: Atheism - includes links to organizations and websites.

- Religion & Ethics - Atheism at bbc.co.uk.

- Secular Web library -- library of both historical and modern writings, probably the most comprehensive online resource for freely available material on atheism.

- Positive atheism: Great Historical Writings -- historical writing sorted by authors, contains a few items not in the Secular web library.

- Infography about Atheism

- Lion of Judah: Answering atheists -- large directory of apologetic websites.

- About Atheism - part of the About.com family of websites, maintained by Austin Cline.